Summary

Zampanolide and its less active analog dactylolide compete with paclitaxel for binding to microtubules and represent a new class of microtubule-stabilizing agent (MSA). Mass spectrometry demonstrated that the mechanism of action of both compounds involved covalent binding to β-tubulin at residues N228 and H229 in the taxane site of the microtubule. Alkylation of N228 and H229 was also detected in α,β-tubulin dimers. However, unlike cyclostreptin, the other known MSA that alkylates β-tubulin, zampanolide was a strong MSA. Modeling the structure of the adducts, using the NMR-derived dactylolide conformation, indicated that the stabilizing activity of zampanolide is likely due to interactions with the M-loop. Our results strongly support the existence of the luminal taxane site of microtubules in tubulin dimers and that microtubule nucleation induction by MSAs may proceed through an allosteric mechanism.

Introduction

Increasing life expectancy from improved vaccination and hygienic practices has placed neoplastic diseases into the forefront as a major cause of mortality. Among treatment options, chemotherapy is commonly employed and often successful.

Chemotherapy employs a chemical agent that is selective for different cell types deriving from differences in the biology of the body’s cells. A major difference between cancer cells and most healthy cells is that transformed cells divide much faster. Tubulin, the main component of the microtubule (MT) cytoskeleton, is an obvious target for compounds designed to block cell division. MTs are highly dynamic in mitosis, and therefore dividing cells are particularly susceptible to agents that target tubulin (Dumontet and Jordan, 2010).

MT-stabilizing agents (MSAs) promote MT assembly by blocking disassembly of the GDP-bound form of tubulin and promoting assembly of the GTP-bound form. Among MSAs, paclitaxel (PTX) and docetaxel (DCX) are two very efficacious chemotherapeutic agents. Widely used for the treatment of breast, ovarian and lung cancer, their clinical use is however severely hampered by low solubility and the development of resistance due to overexpression of both the P-glycoprotein (P-gp) drug efflux pump and βIII-tubulin. Thus, compounds that are less susceptible to P-gp drug efflux may have novel pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles, including the potential for oral administration (Dumontet and Jordan, 2010). Tubulin modulators devoid of the problem of P-gp-mediated drug efflux are thus needed. A large number of compounds with MSA activity have been investigated in this context. Among these compounds, cyclostreptin (CS) (Edler et al., 2005; Sato et al., 2000) has a novel mechanism of action. By covalently binding to tubulin, CS overcomes P-gp-mediated multidrug resistance (MDR) (Buey et al., 2007); however, its high chemical instability and low potency preclude its use as a lead compound. Nevertheless, an interesting feature of CS binding was that it occurred, at least partially, to the type I pore of MTs, a fenestration in the MT wall close to the PTX site. The pore thus contains a transient binding site for taxanes (Buey et al., 2007; Díaz et al., 2003) on their way to the luminal site (Nogales et al., 1999). Binding to the pore produces the same cytotoxic effects as binding to the luminal site (Barasoain et al., 2010), indicating that this pore site can be probed as a new druggable binding site on the MT. Binding to these two sites on β-tubulin, moreover, is mutually exclusive (Díaz et al., 2005). The third MSA site is entirely distinct from the taxane site and is targeted by the natural products laulimalide (LAU) and peloruside A (PLA) (Bennett et al., 2010; Khrapunovich-Baine et al., 2011; Pera et al., 2010; Pryor et al., 2002).

Zampanolide (ZMP) is a novel MSA chemotype originally isolated in 1996 from the marine sponge Fasciospongia rimosa (Tanaka and Higa, 1996). The compound has a highly unsaturated, 20-membered macrolide ring and an N-acyl hemiaminal side chain (Figure 1). Field et al. discovered that tubulin was the target for this new cytotoxic chemotype and that its mechanism of action was that of an MSA, promoting tubulin assembly and blocking cells in G2/M of the cell cycle (Field et al., 2009).

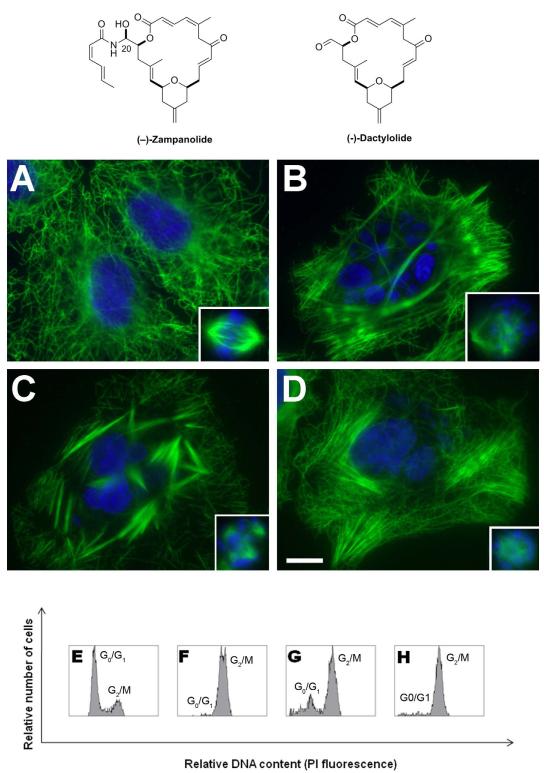

Figure 1.

Upper panel: Chemical structures of ZMP and DAC. Middle panel: Cellular effects of DAC and natural and synthetic ZMP on the MT network, nuclear morphology and cell cycle of A549 lung carcinoma cells. Micrographs of A549 cells incubated for 24 h with (A) DMSO, (B) 10 μM DAC, (C) 50 nM synthetic ZMP and (D) 100 nM PTX. MTs (green) were shown by immunostain with an α-tubulin monoclonal antibody, and DNA (blue) was shown by staining with Hoechst 33342. Insets are mitotic spindles from the same preparation. The scale bar represents 10 μm. Lower panels: Effect of the compounds on the cell cycle of A549 cells as measured by flow cytometry. Cells were treated with DMSO (E), 10 μM DAC (F), 10 nM synthetic ZMP (G) or 20 nM PTX (H). The graphs show the proportions between cells in the G0/G1 phase of the cell cycle and those in the G2/M phase containing double the amount of DNA.

The macrolide (+)-dactylolide (DAC) (Figure 1) was isolated from the sponge Dactylospongia sp. (Cutignano et al., 2001). (+)-DAC is structurally related to (−)-ZMP, but the two compounds have opposite absolute configurations of their otherwise identical macrolactone core. In this work, we investigated the non-natural enantiomer (−)-DAC for comparison with (−)-ZMP for its cytotoxic and antitubulin properties, since (−)-DAC only lacks the hemiaminal side chain of (−)-ZMP. In this study, the location of the ZMP/DAC binding site on MTs, their mechanisms of binding, and the conformation of the bound (−)-DAC have been investigated.

Results

Cellular activity of the compounds and comparison of natural and synthetic ZMP

The activities of natural and synthetic ZMP and synthetic DAC were tested. Both ZMP preparations had equivalent cytotoxicity for A2780 cells in the nM range, while DAC was cytotoxic in the low μM range (Table 1). ZMP and DAC were equally active in the sensitive (A2780) and in the MDR cells (A2780AD). Synthetic ZMP (50 nM) induced abundant, characteristic short MT bundles in A549 cells; in comparison bundles in cells treated with 100 nM PTX or 10 μM DAC were longer and less abundant (Figure 1 A-D). In all cases micronucleated cells were observed. Likewise, at the above doses PTX and DAC induced aberrant mitotic spindles that were mostly mono- or bipolar. With ZMP, the aberrant mitotic cells mostly displayed multiple asters. When A549 cells were incubated for 20 h with serial dilutions of these drugs, maximal drug effects (more than 90% of the cells in the G2/M phase of the cell cycle) occurred with 10 μM DAC, 10 nM ZMP or 20 nM PTX (Figure 1 E-H).

Table 1.

Cytotoxicity of DAC and natural and synthetic ZMP on the growth of two human ovarian carcinoma cell lines. [[a]]

| Compound | A2780 (nM)[[b]] | A2780AD (nM)[[b]] | R/S[[c]] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Natural ZMP[[d]] | 1.9 ± 0.2 | 2.2 ± 0.3 | 1.2 |

| Synthetic ZMP | 1.4 ± 0.3 | 1.5 ± 0.4 | 1.1 |

| DAC | 602 ± 100 | 1236 ± 180 | 2.1 |

| PTX | 0.46 ± 0.10 | 1065 ± 101 | 2315 |

IC50 values of the ligands determined in ovarian carcinoma cells A2780 and P-gp overexpressing A2780AD cells.

IC50 values (nM) are the mean ± SEM of three independent assays.

The relative resistance of the A2780AD cell line obtained by dividing the IC50 of the resistant cell line by that of the parental A2780 cell line.

Previously determined IC50 values of natural ZMP (Field et al., 2009) in A2780 and A2780AD cells were 7.1 ± 0 nM and 7.5 ± 0.6 nM respectively. The difference could be caused by assay differences.

ZMP binds irreversibly to tubulin, stoichiometrically inducing its assembly in a PTX-like manner

Strong MSAs that bind to the PTX or the LAU/PLA site stoichiometrically promote MT assembly in conditions where MT assembly either does not occur or is inhibited (Mooberry et al., 1999; Parness and Horwitz, 1981; Pera et al., 2010). The ability of both natural and synthetic ZMP to promote MT assembly was tested in PEDTA4 buffer (10 mM NaPi, 1 mM EDTA, 4 mM MgCl2, 1 mM GTP at pH 6.7). In this buffer, tubulin is unable to assemble unless a strong MSA is present. In these conditions, ZMP was able to induce assembly of tubulin with a critical concentration (Cr) (Oosawa and Asakura, 1975) of 4.1 μM, requiring little excess compound to induce maximal assembly (Figure 2A). The assembled polymers were found to be MTs by electron microscopy (Inset Figure 2A). Natural and synthetic ZMP behaved identically.

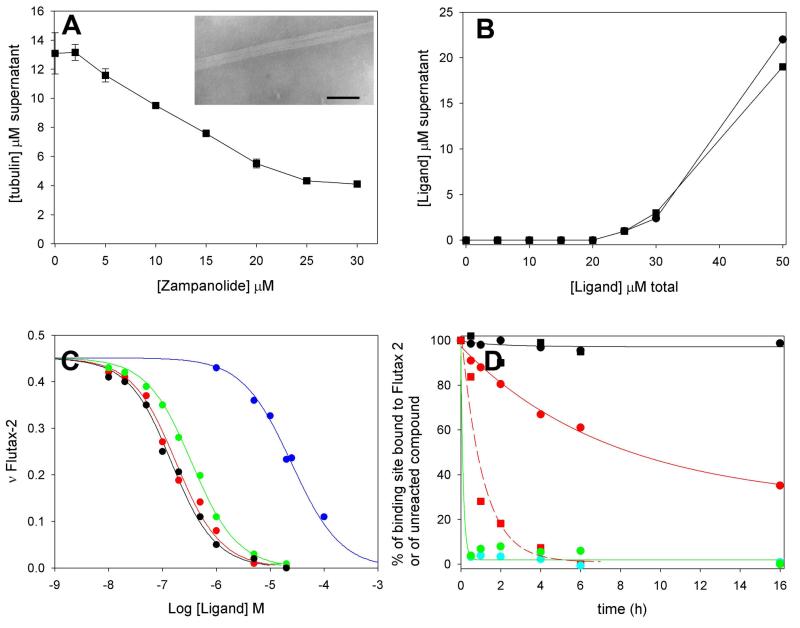

Figure 2. Biochemical characterization of the ligand-tubulin interaction.

(A)-Stoichiometric MT assembly induced by ZMP. MT assembly in PEDTA6-1 mM GTP buffer with increasing concentrations of ZMP at 37°C. Inset.- Representative electron micrograph of a ZMP-induced MT. Bar represents 100 nm. (B) Stoichiometric reaction of ZMP (circles) or DAC (squares) with glutaraldehyde-stabilized MTs. Ligand in the supernatant represents compound that has not reacted with the PTX sites in the glutaraldehyde-stabilized MTs. (C) Representative competition experiments between Flutax-2 and MSAs for binding to MTs. Displacement of Flutax-2 (50 nM) from MT binding sites (50 nM) by ZMP (black line and symbols), DCX (red line and symbols), epothilone A (green line and symbols), and DAC (blue line and symbols). (D) Kinetics of the reaction of the ligands with MTs. Circles, remaining Flutax-2 binding sites when incubated with DMSO (black), natural ZMP (cyan), synthetic ZMP (green), DAC (red). Squares, unreacted DAC when incubated with buffer (black) or stabilized binding sites in MTs (red). Solid black line, fitting of the decay of the binding of the sites incubated with DMSO; solid red line, fitting of the decay of the binding sites incubated with DAC; dashed red line, fitting of the decay of the unbound DAC when incubated with sites; solid green line, fitting of the decay of the binding sites incubated with ZMP.

Under conditions in which tubulin is able to assemble without an MSA (3.4 M glycerol, 10 mM NaPi, 1 mM EGTA, 6 mM MgCl2 buffer, pH 6.7 (GAB buffer) + 1 mM GTP), ZMP was a very strong assembly inducer (Cr= 0.81 ± 0.16 μM), with potency similar to that of DCX (Cr= 0.65 ± 0.05 μM). DAC also significantly enhanced tubulin assembly, reducing the Cr measured in the absence of ligand (3.3 ± 0.30 μM) by roughly 30% (Cr= 2.10 ± 0.15 μM) to the level of other weak assembly inducers (sarcodictyins A and B; CS) (Buey et al., 2005). Moreover, it was not possible to extract ZMP or DAC from the MT pellets, suggesting that these compounds bind to tubulin in an irreversible manner. Other MSAs, such as PTX or PLA, which are reversible binders, are easily recovered from MT pellets (Díaz and Andreu, 1993), (Pera et al., 2010).

To check ZMP binding to tubulin with a direct binding assay, either 25 μM PTX binding sites in crosslinked, stabilized MTs were incubated with substoichiometric (20 μM) amounts of ZMP or DAC, or MT formation was induced by 20 μM compound in conditions in which tubulin can self-assemble (25 μM in GAB buffer). In the absence of stabilized MTs or tubulin, both DAC and ZMP at 20 μM were recovered from the supernatant. However, in the presence of stabilized or native assembled MTs, ZMP could not be extracted from supernatants or pellets, indicating irreversible binding within 30 min. DAC behaved similarly, but at least 4 h were required for a complete reaction. Thus, the kinetic rate of the DAC interaction is much slower than the ZMP interaction.

The stoichiometry of the reaction was determined by incubating 25 μM PTX binding sites in crosslinked, stabilized MTs with increasing amounts of ZMP or DAC (Figure 2B). The 25 μM PTX binding sites can react with up to 25 μM ZMP or DAC, and all the excess remains in the supernatant, thus indicating that the interaction of ZMP and DAC with MTs proceeds with a 1:1 stoichiometry.

ZMP and its analogs were PTX biomimetics and did not interfere with PLA binding

In an initial experiment, ZMP was evaluated for potential inhibition of the binding of [3H]PTX and/or [3H]PLA to preformed MTs. ZMP strongly inhibited PTX binding (67% inhibition), but not PLA binding (13% inhibition) (control experiments showed that discodermolide inhibited 91% of PTX binding and 12% of PLA binding, while LAU inhibited 90% of PLA binding but not PTX binding). Thus, we concluded that ZMP, and presumably DAC, were new agents that bound to the same site on MTs as PTX.

The compounds were therefore tested for their ability to displace Flutax-2, a fluorescent PTX biomimetic, from stabilized, crosslinked MTs (Buey et al., 2005). ZMP and DAC were compared with DCX and epothilone A. All four compounds tested displaced Flutax-2 from its binding site (Figure 2C), with different apparent binding affinities. The apparent binding constant of ZMP at 35°C (214×106 M−1) was 150 times greater than that of DAC (1.35×106 M−1), indicating a strong influence of the side chain on the binding reaction (Table S1). The apparent binding constants of the compounds increased with temperature (ZMP Kbap26°C=137±29×106 M−1, Kbap42°C=424±175×106 M−1; DAC Kbap26°C=0.57±0.10×106 M−1, Kbap42°C=2.14±0.25×106 M−1). This was opposite to the expected results for an enthalpy-driven reaction, which is the usual case with noncovalently binding MSAs (Buey et al., 2005; Matesanz et al., 2008), and similar to the behavior observed with CS binding to MTs (Edler et al., 2005).

In order to check blocking of the taxane pore binding site in MTs, 200 nM PTX binding sites in stabilized MTs preincubated with 200 nM 7-Hexaflutax (which binds to the pore site (Barasoain et al., 2010)) were incubated with ZMP. No 7-Hexaflutax was bound in the presence of ZMP at concentrations at least stoichiometric with the tubulin, indicating that binding of ZMP to the MTs blocked access to the pore site.

Kinetics of binding of ZMP and DAC to the PTX site in MTs

The kinetics of binding of ZMP and DAC were studied both by HPLC (measuring unreacted compound) and fluorescence methods (monitoring the decrease in available binding sites for Flutax-2) (Figure 2D). These two experiments were designed to monitor two different processes and thus to provide an estimate of the kinetics of the covalent reaction once the compound was noncovalently bound to the binding site. In the first case, MTs were pelleted and the concentration of unreacted compound measured, so both covalently reacted compound and noncovalently bound compound were pelleted, and thus the measurement accounts for the kinetics of the noncovalent binding reaction. The second experiment measured the binding sites that have not yet reacted and so are available for exchange with Flutax-2. In this case, the kinetics of the covalent reaction is measured. If the covalent reaction between the compound and the sites is immediate, no difference should be observed between the two measurements. However, if the reaction is slow and the noncovalently bound compound can exchange with unbound compound, a significant difference between measurements should be observed.

ZMP rapidly reacted with MTs, and the covalent reaction was complete within 30 min. No differences were observed between both measurements, indicating the covalent reaction immediately follows noncovalent binding. In contrast, a significant difference was observed between the Flutax-2 exchange and HPLC measurements of the kinetics of DAC binding to MTs. The covalent reaction with DAC was slower than that of ZMP, with an apparent kinetic rate constant on the order of 0.12 h−1 (as measured by Flutax-2 exchange), while the noncovalent reaction as measured by HPLC was 10 times faster (apparent kinetic rate constant of the order of 1 h−1) than the covalent reaction. This indicates a significant delay in the covalent reaction of DAC with the binding site following formation of the noncovalent complex and that the noncovalently bound compound is in fast exchange with the medium.

ZMP and DAC react with the luminal binding site of MTs and dimers

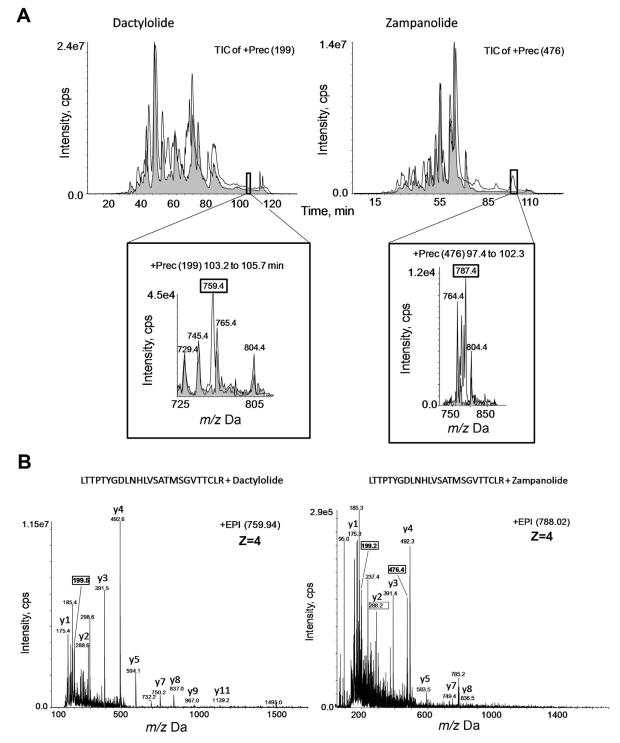

To characterize the interaction of ZMP and DAC with MTs and dimers, targeted MS experiments using a hybrid triple-quadruple mass analyzer were performed. Specific ion filtering of the ZMP- or DAC-tubulin adducts was carried out by Precursor Ion Scanning (PIS) experiments using 476 m/z as the diagnostic ion for the ZMP-derived tryptic peptide (See Supplementary Information).

The comparative study between the corresponding PIS chromatographic runs pinpointed the ZMP and DAC binding sites (Figure 3A, highlighted area); some chromatographic peaks looked altered after the reaction but showed the same mass composition. The comprehensive analysis of the MS/MS spectra of these ions revealed the β-tubulin-derived peptide spanning sequence 219-LTTPTYGDLNHLVSATMSGVTTCLR-243 as the ZMP and DAC reactive site in MTs (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. MS analyses of DAC and ZMP binding to MTs.

(A) Total ion chromatogram (TIC) of the PIS experiment at selected m/z values for control MTs (MTB) (grey tracings) or MTB treated (white tracings) with DAC (Left-hand Panel) or ZMP (Right-hand Panel) in the triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer. The chromatograms are very similar except for subtle differences in the hydrophobic region (black boxes in the chromatograms). These differences are highlighted in the corresponding expanded area, which displays some differential masses corresponding to tubulin-derived tryptic peptides bound to DAC (left) or ZMP (right). (B) Fragmentation MS/MS spectra for the tubulin-derived tryptic peptides bound to DAC (left) or to ZMP (right) as obtained in a low resolution triple quadrupole system. Signals correspond to peptides with four charges (z=4). Squared numbers correspond to DAC or ZMP fragments. The β-tubulin-derived tryptic peptide 219-LTTPTYDGLNHLVSATMSGVTTCLR-243 contains the DAC and ZMP interaction domain. Some of the main fragments from the y-carboxy fragmentation series are labeled.

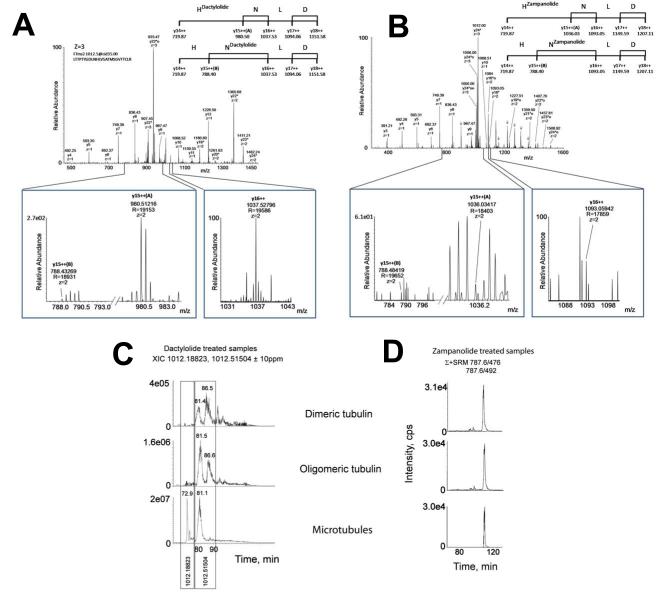

To pinpoint the reactive residue, we performed high resolution MS (HRMS) analyses in the Orbitrap Elite system. N228 and H229 were determined to be the residues that reacted with both DAC and ZMP (Figures 4A and 4B, respectively). The expanded areas demonstrate that there are two possibilities for the doubly-charged fragment ion y15 depending on whether N228 or H229 is the modified residue, with the rest of the y ions common to both adducts. If N228 bears the adduct, then the value for the doubly-charged y15 ion must be 788.40 Da, for both DAC and ZMP. In contrast, the value for this ion must be 980.50 Da (for DAC) or 1036.03 (for ZMP) if the modified residue is H229. The existence of ions y15(A) and y15(B) indicates that both the H229 and the N228 modifications, respectively, occurred and the two y15 fragments are clearly detected in the MS2 spectra, although y15(A) is significantly stronger that y15(B).

Figure 4. MS characterization of the DAC and ZMP tubulin adducts and reaction modes of the compounds with unassembled tubulin and MTs.

High resolution MS/MS spectra (R=30000) for the triply-charged tubulin-derived trytic peptides bound to DAC (A) or to ZMP (B) acquired on the Orbitrap Elite mass spectrometer. The asterisk marks the mass increase in the y ions bearing the bound molecule (DAC or ZMP). Water losses are labeled with the symbol o. Some ions corresponding to the accompanying a series are marked with an arrow. The value of the z indicates the charge state on each fragment. Detailed information about the key fragment ions (in the y series) documenting the precise modified residue (N228 or H229) is presented. (C) DAC interaction with dimeric tubulin, oligomeric tubulin and MTs. Extracted ion chromatograms (XIC) for the triply-charged tubulin-derived tryptic peptide of the DAC-treated samples at m/z 1012.18823 and 1012.51504. (D) ZMP interaction with dimeric tubulin, oligomeric tubulin and MTs. SRM assays, the mass of the expected triply-charged β-tubulin ion was monitored in quadrupole 1 (Q1), and two different transitions were studied in quadrupole 3: 476 m/z (from ZMP fragmentation) or 492 m/z (ion y4).

While we observed only one labeled peak with ZMP (not shown), indicating that both adducts coelute, for DAC we isolated 3 peptides that eluted differently in the HPLC, suggesting three reaction modes (Figure 4C). The first peak eluted at 73 min, the second and most prominent peak at 81 min, and the third, which was very weak, at 86 min. All these species spanned the 219-243 sequence, but while peaks 1 and 2 were labeled at N228 and H229, peak 3 was only labeled at H229. However, as indicated by a high resolution fragmentation spectrum (Figure S2), the mass of the N-DAC residue in the 73 min peptide was 1 Da lower than the expected mass of the adduct observed in the 81 and 86 min peptides.

The reaction of ZMP and DAC with unassembled tubulin was also studied. Both ZMP and DAC reacted with dimeric and oligomeric tubulin in less than 4 h (data not shown). MS analysis of the adducts (Figures 4C and D) revealed that the compounds reacted at the same residues (N228 and H229) as with MTs, indicating that the binding site was also present in unassembled tubulin. However, while the reaction with ZMP was fast and extensive, the reaction with DAC was weaker and required longer incubation times, as had also been the case with MTs.

The ZMP adduct with unassembled tubulin was the same as that observed with MTs, indicating that the reaction mode is similar whatever the association state of the protein. However, this was not the case with DAC. With MTs, three different reaction products with DAC were observed by HPLC, while with dimeric and oligomeric tubulin the 73 min peptide was not present. Moreover, the proportions of the 81 and 86 min peptides varied with the aggregation state of tubulin. With oligomeric tubulin (formed with 1.5 mM Mg2+), the DAC adduct at 81 min was the major component; with dimeric tubulin (in the absence of Mg2+), the major product was the 86 min adduct modified at H229.

Bioactive conformation of DAC bound to MTs

The bioactive conformation and the binding site of DAC bound to the tubulin α,β-heterodimer and to MTs were determined using ligand-based NMR techniques. These methods (mainly Transferred Nuclear Overhauser Effect (TR-NOESY) (Ni and Zhu, 1994) and Saturation Transfer Difference (STD) (Mayer and Meyer, 2001)) rely on the existence of a dissociation rate that is fast on the relaxation time scale. Therefore, since the irreversible reaction of DAC with tubulin is rather slow (k=0.12 h−1) as compared with the reversible reaction (k=1 h−1), the TR-NOESY and STD signals obtained should mainly arise from DAC not yet covalently bound to MTs or dimers. The intensity of DAC signals in the 1H 1D-NMR spectra slowly decreased with time at a kinetic rate similar to that determined for the irreversible reaction (k=0.12 h−1), as expected when the ligand reacts with tubulin, indicating blocking of the binding site. This situation was not observed for DCX or discodermolide binding to MTs or tubulin dimers (Canales et al., 2011).

STD-NMR experiments detect saturation transfer from a given target protein to a bound ligand. Only bound ligands show STD signals and, as in any NOE-type experiment, the observed STD effect depends on the distance between the protein and ligand protons, thus providing a useful tool to detect the ligand epitope. Binding of DAC to MTs in D2O, 10 mM KPi, 0.1 mM GMPCPP (a slowly hydrolyzable GTP analog that specifically stabilizes MTs (Jiménez-Barbero et al., 2006)), 6 mM MgCl2, pH 7.0, could be easily detected by STD (Figure 5A). A comparison of the STD profiles of DAC bound to unassembled tubulin and to MTs indicated that the binding epitopes were nearly identical, which was not the case for DCX but was the case for discodermolide (Canales et al., 2011). In both cases, with DAC, the STD effect of all protons was fairly homogeneous throughout the complete skeleton, thus suggesting an extensive interaction of the molecule with the binding site.

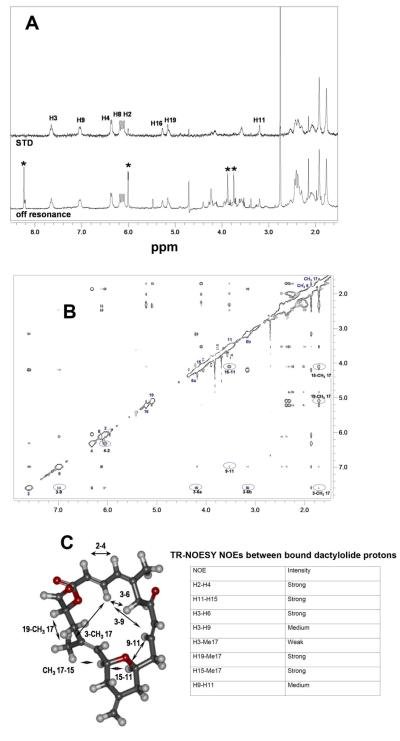

Figure 5. NMR characterization of the DAC-tubulin interaction.

(A) Off-resonance NMR experiment (600 MHz) (lower line) and STD spectra (upper line) of DAC bound to MTs. (B) TR-NOESY spectra (mixing time: 80 ms) of DAC in the presence of MTs (D2O, 310 K). (C) Bioactive conformation of DAC bound to MTs. The table shows the relative intensity of the TR-NOESY NOE signals between significant protons in the bound compound.

The bioactive conformation of DAC bound to the tubulin α,β-heterodimer and MTs was deduced by analysis of the TR-NOESY cross peaks, as shown in Figure 5B. Several key negative NOEs between remote protons in the molecule were detected in the presence of either MTs or unassembled tubulin (Table in Figure 5C), allowing the determination of the bioactive conformations. The obtained distances indicated that the bound conformations were essentially identical in both cases (Figure 5C). Moreover, 2D-ROESY experiments of free DAC in buffer (Figure S3) indicated that the conformation of the compound free in water is essentially identical, adding confidence to the determined structure.

Molecular modeling

In order to rationalize the interaction of ZMP with MTs and tubulin, the NMR-determined bioactive conformation of DAC was used to build a ZMP bioactive structure, and both compounds were docked into the MT luminal site.

Since the covalent reaction occurred at N228 and H229, and the STD and TR-NOESY signals observed for DAC bound to MTs arose from free compound just released from its binding site, we could not assume that the signals observed in the MT bound epitope corresponded to the interaction of the compound with the luminal site, which shows a slow dissociation rate for MSAs that do not alkylate tubulin, i.e., taxanes (Díaz et al., 2000) or epothilones (Díaz and Buey, 2007). It is more likely that these NMR signals were caused by a temporary interaction of DAC with the pore site in MTs, where no covalent reaction occurred, and fast exchange with the medium would be expected. On the other hand, the interaction of MSAs with dimeric tubulin is not yet well characterized and is likely to be nonhomogeneous, i.e., binding may involve both the luminal and the (partial) pore sites (Canales et al., 2011). Therefore, the STD determined binding epitope could not be employed to model ZMP bound to the luminal site. However, since the TR-NOESY-derived conformation of DAC was identical for binding to dimers and MTs, it is likely this conformation is stable and can be employed as a starting point to find the interaction with the luminal binding site using standard docking techniques.

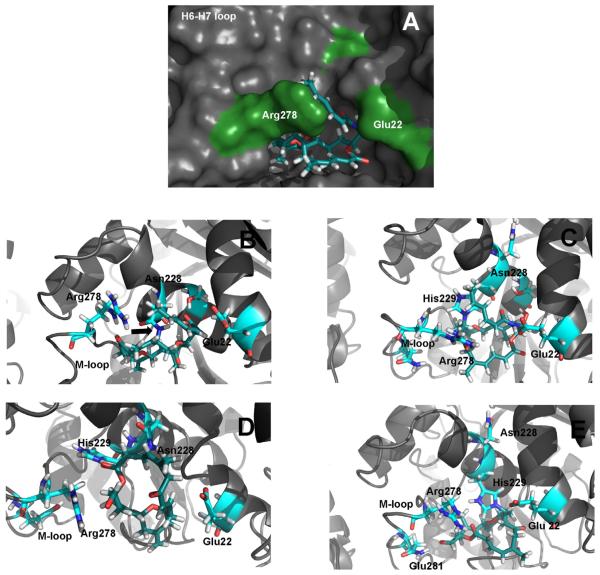

The best poses of the ZMP and DAC pre-reaction complexes were selected from those with minimal interaction energy, as calculated from Autodock, and we took into account that at least one of the likely reactive moieties (the double bond in conjugation with the ester group, the enone moiety, or the α,β-unsaturated amide moiety of the side chain, in the case of ZMP, or the aldehyde group, in the case of DAC) should be close to N228 and/or H229. Those Autodock poses with the α,β-unsaturated ester moiety close to N228 and the enone moiety (the best Michael acceptor due to the lack of cross conjugation) close to H229, were found to be compatible with acceptable dockings into the PTX site (Figure 6A).

Figure 6. Molecular modeling of the tubulin-compound adducts, based on the DAC conformation determined by NMR.

(A) Model of the ZMP noncovalent prereaction complex. (B) Binding model following the covalent reaction of ZMP with tubulin at N228. The arrow indicates the C-N bond formed between the ligand and the Asn side chain. (C) Binding model following the covalent reaction of ZMP with tubulin at H229. (D) Binding model following the covalent reaction of DAC with tubulin at N228. (E) Binding model following the covalent reaction of DAC with tubulin at H229.

In order to model the adduct with N228, the orientation of the N228 side chain was then modified to point towards the binding pocket in order to build the covalent complexes. Considering the dockings observed, the 1,4-addition most likely involves the α,β-unsaturated ester moiety within the macrocycle. The adduct with H229 was modeled without any modification of the structure.

Given the fact that only one molecular weight was observed for the adducts of the reaction of ZMP with MTs, oligomeric tubulin, and dimeric tubulin, and that the high resolution spectra indicated that the 73 min peak (see above) was a mixture of DAC-modified peptides with the adduct at either N228 or H229, the 1 Da mass difference between the 73 min peak and those eluting at 81 and 86 min could not be due to inhomogeneities in the protein sequence but should be related to ligand differences. It is conceivable that during the digestion process of MTs which is performed in NH4HCO3 buffer (Buey et al., 2007), the aldehyde moiety is partly transformed into the imine. This would generate a −1 mass difference relative to the aldehyde, which would account for the peak eluting at 73 min. The different H229 adducts that elute at 81 and 86 min could represent reactions with the two different nitrogens of the imidazole ring of H229, which is probably protonated under the conditions (pH 6.7) of the experiment (Matesanz et al., 2008). The most likely reason for not observing the 81 and 86 peaks in the analysis of the ZMP adduct is the lower polarity of the modified peptide, due to the ZMP side chain. This largely increases the retention time of the adduct that elutes close to the maximum acetonitrile concentration (90%) (Figure 4D), thus precluding resolution of both peaks.

Discussion

ZMP, a new chemotype targeting the PTX binding site, indicates the existence of the luminal site in unassembled tubulin

From a thermodynamic point of view, it is straightforward that, if MSAs bind to MTs and not to unassembled tubulin, they will shift the assembly equilibrium towards MTs. However, PTX biomimetics induce MT assembly in conditions in which tubulin is normally unable to assemble, e.g., in the absence of GTP or even with GDP bound in the E-site, and thus no MTs exist (Díaz and Andreu, 1993; Parness and Horwitz, 1981). Thus, PTX biomimetics must play a role in nucleation, presumably by binding to unassembled tubulin with low affinity, thereby either inducing a conformational change that activates tubulin (allosteric mechanism) or joining two subunits to produce a high affinity binding site from two low affinity sites (matchmaker mechanism) (Díaz et al., 1993; Reese et al., 2007; Sanchez-Pedregal et al., 2006).

Direct binding of ligands to unassembled tubulin at residue T220 in the pore site has been observed by MS techniques employing CS (Buey et al., 2007). NMR and biochemical studies have confirmed that DCX and discodermolide bind with low affinity to dimeric tubulin (Canales et al., 2011). Initial seminal NMR work from the group of Carlomagno has also shown low affinity binding of MSAs to a non-homogeneous tubulin preparation (Carlomagno et al., 2003a; Carlomagno et al., 2003b; Sanchez-Pedregal et al., 2006). However, from these studies it was not possible to determine whether binding was at the pore site. Binding at the pore site in unassembled tubulin would indicate that the nucleation mechanism of MSAs is of the matchmaker type (the full pore site would be formed from two half sites). In contrast, binding at the luminal site in unassembled tubulin would indicate that the nucleation mechanism is of the allosteric type (the luminal site is present in a low affinity conformation that becomes high affinity after assembly (Reese et al., 2007)). Alternatively, low affinity binding of an MSA to the luminal site could in itself induce an allosteric effect, activating tubulin to induce nucleation.

Our results strongly suggest that the luminal site exists in unassembled tubulin, since both ZMP and DAC attach to unassembled tubulin and react with residues N228 and H229. Thus, as previously proposed (Canales et al., 2011; Reese et al., 2007), MSAs bind to the luminal site in unassembled tubulin and not only to the pore site, as was seen with unassembled tubulin and CS (Buey et al., 2007). These different results with different MSAs that react covalently with tubulin suggest that nucleation of MTs may proceed by two alternative mechanisms (matchmaking and allosteric), as previously discussed (Díaz et al., 1993).

Biochemical mechanisms of MT induction by ZMP. Covalently binding MSAs are able to overcome P-gp mediated MDR

Since ZMP binds irreversibly either at position N228 or at position H229 of the β-tubulin subunit with a 1:1 stoichiometry, all of the compound reacts with the luminal site. The lack of superstoichiometric binding, either reversible or irreversible, indicates no interaction at the pore. Thus, binding to either site excludes binding at the other, and this might involve a switching element. The absolute lack of interaction of 7-Hexaflutax with MTs with covalently bound ZMP indicates that binding at the luminal site is specific and alters and/or blocks the pore site, thus preventing simultaneous binding to it.

As was the case for CS, the covalent mechanism of action of ZMP and DAC overcame the P-gp mediated MDR mechanism, since the compound was equally active in the sensitive (A2780) and MDR cells (A2780AD) (although it cannot be excluded that the ligands were poor substrates of P-gp). Thus, the design of covalent binders might be a promising strategy to fight this resistance mode in cancer chemotherapy.

Structure of the covalent complexes of ZMP and DAC and the structural basis of the MT stabilizing effect

The possible different complexes between ZMP or DAC and tubulin were studied using molecular modeling techniques in order to understand the stabilization effect observed.

The modeling studies of ZMP and DAC with the luminal binding site of MTs indicated that in both cases the compounds bound to the bottom of the binding pocket In the bound state dactylolide presents a globular shape that it is buried in the binding site of the protein, concordant with the fact that the observed STDs are fairly homogeneous. In complex with N228 (Figure 6B), the north side of the macrolide ring was held in place by the covalent interaction with N228. It is notable that in this complex the side chain of ZMP was involved in interactions with N228. These interactions involve hydroxyl and carbonyl groups of the side chain forming two hydrogen bonds with both the amide and the peptide backbone of N228. In addition, the carbonyl of N228 formed a hydrogen bond with H229, as did the hydroxyl of the side chain with S232. Both interactions enhanced the stability of the resulting complex. The opposite face of the ZMP side chain maintained contact with the lateral side of the binding site (E22). The oxygen of the ketone moiety on the eastern side of the ZMP macrolide established a strong interaction with R278 in the S7-H9-loop (M-loop) in a similar way to PTX, while the western side of the macrolide lay over H7. The methylene moiety at position 13 occupied a hydrophobic pocket between the H7, S9-S10 loop and the M-loop formed by A233, F272, P274, T276 and L371. In the case of the complex with H229 (Figure 6C), the interactions observed were essentially identical, except those established with the side chain of N228, which in this complex pointed towards the E-site nucleotide, and there was an additional H-bond between the hydroxyl of the side chain of ZMP and K19.

In the complex of DAC bound to N228 (Figure 6D), the orientation of the macrolactone ring was inverted compared with the ZMP ring (note that the natural product (+)-DAC is the enantiomer of the compound used in this study). Although the north side was held by the covalent interaction with N228, in this complex R278 interacted with the oxygen of the ester. The eastern side of the molecule was in contact with the bottom of the binding site, filling the space that the side chain occupied in complex A with ZMP. In this case, the methylene moiety at position 13 interacted directly with the S9-S10 loop and occupied a small pocket formed by K19, E22, V23, R369 and G370. In the complex with DAC bound to H229, the ligand was slightly displaced, being closer to the M-loop (Figure 6E) with the methylene moiety interacting with the hydrophobic pocket formed by A233, S236, F272, P274, P360, and S374 which results in an additional strong interaction with the M-loop between the aldehyde and Q281.

Finally, our model explains the strong MT stabilizing activity observed with ZMP. Covalent binders are missing a property common to other MSAs. With the epothilones, taxanes, and discodermolide, the MSA binds tighter to the MTs than to unassembled tubulin (Canales et al., 2011; Díaz et al., 1993). Thus, the higher free energy of binding towards the assembled species will shift the assembly equilibrium towards it (Wyman and Gill, 1990), independent of the structural effect on the assembled species. However, in the case of covalent binders, the equilibrium has to be displaced through a structural allosteric effect, i.e., the modified tubulin should have a higher affinity for the MT than does the unmodified tubulin. In the case of taxanes, the strong stabilization of the S7-H9 loop has been described as the main structural MT stabilizing feature after taxane binding (Amos and Lowe, 1999; Lowe et al., 2001; Nogales et al., 1999). A similar mechanism may be the reason for the strong MSA activity observed with ZMP. In the case of CS, the other MSA with a covalent mechanism of action (which partially reacts with the pore site in MTs and thus does not interact with the M-loop in this binding pose), the observed stabilizing effect is weaker (Buey et al., 2007; Edler et al., 2005).

Significance

ZMP, a new, strong MSA acting at the PTX site, exerted its action through covalent binding to the luminal site of MTs at N228 or H229. Due to its covalent mechanism of action, ZMP was able to overcome P-gp mediated MDR, as also occurred with CS. In contrast to CS, however, ZMP and DAC also reacted with the same residue in unassembled tubulin, thus providing the first direct evidence of the existence of the luminal site in dimeric tubulin. Formation of MTs with ZMP, including the covalent reaction with N228 or H229, required Mg+2 ions at mM concentrations, as is the case for assembly of tubulin in the presence of taxanes. The MTs formed with ZMP had normal morphology despite formation of the covalent bond, and this indicated a taxane-like stabilization mechanism. Molecular modeling of the tubulin-ZMP complex, employing an NMR-determined bioactive DAC conformation, indicated that the side chain of ZMP stabilized the covalent adduct. The modeling provided a structural explanation for the stronger activity of this compound compared with DAC and indicated that the stabilization mechanism was due to an allosteric effect through interactions of the ligand with the M-loop, as is the case for other MSAs that bind in the PTX site.

Experimental procedures

Proteins and ligands

Purified calf-brain tubulin and chemicals were prepared as before (Díaz and Andreu, 1993) (Andreu, 2007). Stabilized, moderately crosslinked MTs were prepared as before (Díaz et al., 2003; Díaz et al., 2000).

PLA was isolated from Mycale hentscheli collected from Pelorus Sound, New Zealand. Natural ZMP (Figure 1) was isolated from Cacospongia mycofijiensis collected from ’Eua and Vava’u, Tonga as described (Field et al., 2009). (−)-DAC (Figure 1) was prepared as before (Zurwerra et al., 2010). The synthetic conversion of (−)-DAC into (−)-ZMP followed the strategy of (Hoye and Hu, 2003), with subsequent separation of the resulting C20 epimers by preparative RP-HPLC. Details of this work will be presented elsewhere. All spectroscopic properties of synthetic (−)-ZMP were identical with those of the natural product. Aliquots of the compounds were dried to constant weight and dissolved in spectroscopic ethanol (Merck). Their extinction coefficients (ZMP, ε230 = 31000 ± 800 M−1 cm−1, ε264 = 42400 ± 1000 M−1 cm−1; DAC, ε230 = 15700 ± 300 M−1 cm−1, ε278 = 15500 ± 300 M−1 cm−1) were determined in a Thermo Fisher Evolution 300 UV/Vis spectrometer. The extinction coefficients of ZMP were found to be 30% higher than those previously determined ε = 25000 M−1 cm−1, 30000 1 230 ε = M−1 cm− 264 (Tanaka and Higa, 1996). The ε278 of (−)-DAC was comparable with that of (+)-DAC at ε266 (16000 M−1 cm−1); that at 230 nm was 30% higher than that of (+)-DAC at 222 nm (11000 M−1 cm−1) (Cutignano et al., 2001). Both observed (−)-DAC peaks were shifted towards red compared with those of the enantiomer. Drugs were stored as 20 mM stocks at −80°C in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) and analyzed as described in Supplemental Information.

Inhibition of [3H]PTX and [3H]PLA binding to MTs

The inhibition of [3H]PTX and [3H]PLA binding to MTs was measured as described (Edler et al., 2005), with modifications (See Supplemental Experimental Methods).

Biochemical characterization of the ligand-tubulin interaction

Cr’s of ligand-induced tubulin assembly were measured as before (Buey et al., 2005). Polymer structures were checked by transmission electron microscopy as described in Supplementary Experimental Procedures. The apparent binding constants of the ligands to the PTX site in MTs were measured by Flutax-2 displacement (Buey et al., 2005). Blocking of the pore site in assembled MTs was verified by displacement of 7-Hexaflutax, as described for Flutax-2 (Buey et al., 2005), employing 200 nM concentrations of 7-Hexaflutax and sites, due to the lower binding affinity of the compound to MTs (Barasoain et al., 2010). Reaction stoichiometry was calculated by incubating increasing amounts of ZMP and DAC with 25 μM PTX binding sites in stabilized MTs in GAB buffer containing 0.1 mM GTP for 1 h (ZMP) or at least 4 h (DAC) at 37°C. MTs and the irreversibly bound ZMP or DAC were harvested by pelleting at 37°C for 10 min at 50,000 rpm using a TL100.2 rotor in a Beckman Optima TLX centrifuge. PTX (10 μM) was added to the collected supernatant as an internal standard. Unreacted ligands were extracted from the supernatant three times with one reaction volume of CH2Cl2. The extract was dried, and the sample was resuspended in 70% methanol-30% water (35 μL). The samples were analyzed as described in Supplemental Information.

Kinetics of reaction of the ligands with dimeric tubulin and MTs

The kinetics of reaction of compounds with crosslinked MTs was measured by determining the inhibition of Flutax-2 binding to MTs. PTX binding sites (5 μM) in crosslinked MTs in GAB 0.1 mM GTP were incubated with 6 μM test compound (or an equivalent volume of DMSO). At the desired time, 10 μM Flutax-2 was added, and the samples were centrifuged as described above. The amounts of Flutax-2 in the pellet and supernatant were measured spectrofluorometrically (Díaz et al., 2000).

The kinetics of the reaction of the compounds with crosslinked, stabilized MTs and with unassembled tubulin were also measured by HPLC. Tubulin (25 μM) in 10 mM NaPi 1 mM EDTA , pH 7.0 buffer (PEDTA) containing 0.1 mM GTP or in PEDTA containing 1.5 mM MgCl2 and 0.1 mM GTP or 25 μM crosslinked MTs in GAB with 0.1 mM GTP was incubated with 20 μM compounds for different times. Unreacted compound was extracted from the supernatant three times with one reaction volume of CH2Cl2. The extract was dried, and the sample was resuspended in 70% methanol-30% water (35 μL). The samples were analyzed as described in Supplemental Information.

NMR experiments

NMR samples of the ligands bound to dimeric and oligomeric tubulin and MTs were prepared as before (Canales et al., 2011). NMR spectra were recorded at 298 K (dimeric and oligomeric tubulin samples) or 310 K (polymeric tubulin samples) in D2O in an AV-III 700 MHz equipped with a triple-channel cryoprobe, an AVANCE 600 MHz equipped with a triple-channel cryoprobe, or an AVANCE 500 MHz Bruker spectrometer, as previously reported (Canales et al., 2011). 2D-transverse ROESY experiments were performed as described (Canales et al., 2008).

The bioactive conformation of DAC was obtained combining NMR data with molecular mechanics calculations. TR-NOESY experiments were acquired with different mixing times from 80 to 200 ms, and the spectrum with the shortest mixing time was selected for analysis to minimize spin diffusion effects. The calculations were performed using the MacroModel/Batchmin package (version 9.6) (2011a) and the OPLS2005 all-atom force field as implemented in the program Macromodel 9.6 (2011a). Bulk water solvation was simulated using Macromodel’s generalized Born GB/SA continuum solvent model. Conformational searches were carried out using the torsional sampling MCMM search method implemented in the Batchmin program, and 20,000 Monte Carlo step runs were performed. The lowest energy conformer in agreement with the experimental NOEs was selected as representative of the bound conformation.

Molecular Modeling

The conformational search and docking calculations were performed as previously described for studying the interaction of taxanes with tubulin (Canales et al., 2011), employing the bioactive conformation of the DAC ring and considering free all possible torsional angles of the ZMP side chain. The choice of the best pose for each ligand (DAC and ZMP) was made using the scoring function of Autodock4.2 (Morris et al., 1998) taking into account the spatial arrangement of the reactive moieties with respect to N228 and H229. Later, the docked poses chosen were minimized by using Macromodel9.9 (2011a), through several steps of Polak-Ribière conjugate gradient until the energy gradient became lower than 0.05 kJ Å−1 mol−1. The top five binding poses of each ligand were rescored based on a binding free energy approach implemented in Prime3.0 (2011b). A brief overview of these methods is described in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures.

Nano-liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometric analysis of tryptic peptides

Tubulin (20 μM in GAB, 1 mM GTP buffer) was assembled at 37°C for 1 h in the presence of 25 μM ZMP or DAC or DMSO (vehicle). Unassembled tubulin samples were prepared using 20 μM GTP-tubulin in 10 mM NaPi, 1 mM EDTA, 0.1 mM GTP, pH 7.0, without (dimeric tubulin) or with 1.5 mM MgCl2 (oligomeric tubulin) and 25 μM ZMP or DAC or DMSO (vehicle). The aggregation state of the tubulin was checked using a Beckman Optima-XLA centrifuge. The experiments were performed at 20 and 37°C using an angular velocity of 45,000 rpm. Double sector cells of 12 mm optical path were employed in an An50Ti rotor. The sedimentation coefficients were calculated using SEDFIT (Schuck, 2000) and were corrected to 20°C using SEDNTERP (Laue, 1992). Both MTs and unassembled tubulin were processed and digested with trypsin (sequencing grade, Promega, Madison, WI). The digestion solutions were vacuum-dried and dissolved in buffer A (5% acetonitrile, 0.5% acetic acid in water) as described (Buey et al., 2007).

For the ion filtering experiments, the resulting tubulin-derived tryptic peptides from control and ZMP- or DAC-treated samples were on-line injected onto a C18 reversed-phase microcolumn (300 μm ID x 5 mm PepMapTM, LC Packings, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) to remove salts and analyzed as before (Buey et al., 2007) (See Supplemental Information for the detailed setup of the PIS, selected reaction monitoring (SRM) and HRMS analysis). All chromatograms and MS/MS spectra were analyzed by the software packages Analyst 1.5.1 (Applied Biosystems) for the PIS experiments or Proteome Discoverer 1.2.0.208 (Thermo Fisher) for the HRMS data.

Cell biology studies

Human A549 non-small cell lung carcinoma and A2780 and A2780AD ovarian carcinoma cell lines were cultured as before (Buey et al., 2007). Indirect immunofluorescence and cell cycle experiments were performed as before (Buey et al., 2005). Cytotoxicity assays were performed using the MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) cell proliferation assay modified as before (Yang et al., 2007).

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

-Zampanolide covalently binds to the luminal paclitaxel site at β-tubulin N228 and H229.

-Labeling occurs in both tubulin dimers and microtubules.

-Bound zampanolide models indicate interaction with the M-loop at the paclitaxel site.

-Microtubule nucleation may proceed both through matchmaking and allosteric mechanisms.

Acknowledgements

We thank Rhône Poulenc Rorer Aventis for DCX and Matadero Municipal Vicente de Lucas de Segovia for the calf brains for tubulin purification. JRS was supported by a fellowship from “Programa de Cooperación Científica entre el Ministerio de Ciencia, Tecnologías y Medio Ambiente de la República de Cuba (CITMA) y el CSIC”. JF received a short-term fellowship from EMBO and a Professional Development Grant from the Genesis Oncology Trust. This work was supported in part by grants BIO2010-16351 and CTQ2009-08536 from Ministerio de Economia y Competitividad (to JFD and JJB respectively) and grant S2010/BMD-2457 BIPEDD2 from Comunidad Autónoma de Madrid to JFD, the Cancer Society of New Zealand, and the Wellington Medical Research Foundation (to JM). The CNIC is supported by the Ministerio de Ciencia e Innovación and the Fundación Pro CNIC.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Macromodel. version 9.9 Schrödinger, LLC; New York, NY, USA: 2011a. [Google Scholar]

- Prime. version 3.0 Schrödinger, LLC; New York, NY: 2011b. [Google Scholar]

- Amos LA, Lowe J. How Taxol stabilises microtubule structure. Chem Biol. 1999;6:R65–69. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(99)89002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreu JM. Tubulin Purification. In: Zhou J, editor. Methods in Molecular Medicine. Humana Press Inc.; Totowa, NJ: 2007. pp. 17–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barasoain I, Garcia-Carril AM, Matesanz R, Maccari G, Trigili M, Mori M, Shi JZ, Fang WS, Andreu JM, Botta M, et al. Probing the pore drug binding site of microtubules with fluorescent taxanes: Evidence of two binding poses. Chem Biol. 2010;17:243–253. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett MJ, Barakat K, Huzil JT, Tuszynski J, Schriemer DC. Discovery and Characterization of the Laulimalide-Microtubule Binding Mode by Mass Shift Perturbation Mapping. Chemistry & Biology. 2010;17:725–734. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buey RM, Barasoain I, Jackson E, Meyer A, Giannakakou P, Paterson I, Mooberry S, Andreu JM, Díaz JF. Microtubule interactions with chemically diverse stabilizing agents: Thermodynamics of binding to the paclitaxel site predicts cytotoxicity. Chem Biol. 2005;12:1269–1279. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buey RM, Calvo E, Barasoain I, Pineda O, Edler MC, Matesanz R, Cerezo G, Vanderwal CD, Day BW, Sorensen EJ, et al. Cyclostreptin binds covalently to microtubule pores and lumenal taxoid binding sites. Nature Chem Biol. 2007;3:117–125. doi: 10.1038/nchembio853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canales A, Matesanz R, Gardner NM, Andreu JM, Paterson I, Diaz JF, Jimenez-Barbero J. The Bound Conformation of Microtubule-Stabilizing Agents: NMR Insights into the Bioactive 3D Structure of Discodermolide and Dictyostatin. Chemistry Eur J. 2008;14:7557–7569. doi: 10.1002/chem.200800039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canales A, Salarichs JR, Trigili C, Nieto L, Coderch C, Andreu JM, Paterson I, Jiménez-Barbero J, Díaz JF. Insights into the interaction of discodermolide and docetaxel with dimeric tubulin. Mapping the binding sites of microtubule-stabilizing agents using an integrated NMR and computational approach. ACS Chemical Biology. 2011;6:789–799. doi: 10.1021/cb200099u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlomagno T, Blommers MJ, Meiler J, Jahnke W, Schupp T, Petersen F, Schinzer D, Altmann KH, Griesinger C. The high-resolution solution structure of epothilone A bound to tubulin: an understanding of the structure-activity relationships for a powerful class of antitumor agents. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2003a;42:2511–2515. doi: 10.1002/anie.200351276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlomagno T, Sanchez VM, Blommers MJ, Griesinger C. Derivation of dihedral angles from CH-CH dipolar-dipolar cross-correlated relaxation rates: a C-C torsion involving a quaternary carbon atom in epothilone A bound to tubulin. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2003b;42:2515–2517. doi: 10.1002/anie.200350950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutignano A, Bruno I, Bifulco G, Casapullo A, Debitus C, Gomez-Paloma L, Riccio R. Dactylolide, a New Cytotoxic Macrolide from the Vanuatu Sponge Dactylospongia sp. European Journal of Organic Chemistry. 2001;2001:775–778. [Google Scholar]

- Díaz JF, Andreu JM. Assembly of purified GDP-tubulin into microtubules induced by taxol and taxotere: reversibility, ligand stoichiometry, and competition. Biochemistry. 1993;32:2747–2755. doi: 10.1021/bi00062a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz JF, Barasoain I, Andreu JM. Fast kinetics of Taxol binding to microtubules. Effects of solution variables and microtubule-associated proteins. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:8407–8419. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211163200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz JF, Barasoain I, Souto AA, Amat-Guerri F, Andreu JM. Macromolecular accessibility of fluorescent taxoids bound at a paclitaxel binding site in the microtubule surface. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:3928–3937. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407816200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz JF, Buey RM. Characterizing Ligand-Microtubule Binding by Competition Methods. In: Zhou J, editor. Methods in Molecular Medicine. Humana Press Inc.; Totowa, NJ: 2007. pp. 245–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz JF, Menéndez M, Andreu JM. Thermodynamics of ligand-induced assembly of tubulin. Biochemistry. 1993;32:10067–10077. doi: 10.1021/bi00089a023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Díaz JF, Strobe R, Engelborghs Y, Souto AA, Andreu JM. Molecular recognition of taxol by microtubules. Kinetics and thermodynamics of binding of fluorescent taxol derivatives to an exposed site. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:26265–26276. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003120200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumontet C, Jordan MA. Microtubule-binding agents: a dynamic field of cancer therapeutics. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:790–803. doi: 10.1038/nrd3253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edler MC, Buey RM, Gussio R, Marcus AI, Vanderwal CD, Sorensen EJ, Diaz JF, Giannakakou P, Hamel E. Cyclostreptin (FR182877), an Antitumor Tubulin-Polymerizing Agent Deficient in Enhancing Tubulin Assembly Despite Its High Affinity for the Taxoid Site. Biochemistry. 2005;44:11525–11538. doi: 10.1021/bi050660m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field JJ, Singh AJ, Kanakkanthara A, Halafihi T, Northcote PT, Miller JH. Microtubule-Stabilizing Activity of Zampanolide, a Potent Macrolide Isolated from the Tongan Marine Sponge Cacospongia mycofijiensis. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2009;52:7328–7332. doi: 10.1021/jm901249g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoye TR, Hu M. Macrolactonization via Ti(IV)-mediated epoxy-acid coupling: A total synthesis of (−)-dactylolide and zampanolide. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 2003;125:9576–9577. doi: 10.1021/ja035579q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Barbero J, Canales A, Northcote PT, Buey RM, Andreu JM, Díaz JF. NMR determination of the bioactive conformation of peloruside a bound to microtubules. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:8757–8765. doi: 10.1021/ja0580237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khrapunovich-Baine M, Menon V, Yang C-PH, Northcote PT, Miller JH, Angeletti RH, Fiser A, Horwitz SB, Xiao H. Hallmarks of Molecular Action of Microtubule Stabilizing Agents. Effects of Epothilone B,Ixabepilone, Peloruside a, and Laulimalide on microtubule conformation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2011;286:11765–11778. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.162214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laue TM, Shah BD, Ridgeway TM, Pelletier SL. Computer-aided interpretation of analytical sedimentation data for proteins. In: Harding SE, Rowe AJ, Horton JC, editors. Analytical Ultracentrifugation in Biochemistry and Polymer Science. Royal Society of Chemistry; Cambridge: 1992. pp. 90–125. [Google Scholar]

- Lowe J, Li H, Downing KH, Nogales E. Refined structure of alpha beta-tubulin at 3.5 A resolution. J Mol Biol. 2001;313:1045–1057. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.5077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matesanz R, Barasoain I, Yang C, Wang L, Li X, De Ines C, Coderch C, Gago F, Jiménez-Barbero J, Andreu JM, et al. Optimization of taxane binding to microtubules. Binding affinity decomposition and incremental construction of a high-affinity analogue of paclitaxel. Chem Biol. 2008;15:573–585. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayer M, Meyer B. Group epitope mapping by saturation transfer difference NMR to identify segments of a ligand in direct contact with a protein receptor. J Am Chem Soc. 2001;123:6108–6117. doi: 10.1021/ja0100120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooberry SL, Tien G, Hernandez AH, Plubrukarn A, Davidson BS. Laulimalide and isolaulimalide, new paclitaxel-like microtubule-stabilizing agents. Cancer Res. 1999;59:653–660. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris GM, Goodsell DS, Halliday RS, Huey R, Hart WE, Belew RK, Olson AJ. Automated docking using a Lamarckian genetic algorithm and an empirical binding free energy function. J Comput Chem. 1998;19:1639–1662. [Google Scholar]

- Ni F, Zhu Y. Accounting for ligand-protein interactions in the relaxation-matrix analysis of transferred nuclear Overhauser effects. J Magn Reson B. 1994;103:180–184. doi: 10.1006/jmrb.1994.1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nogales E, Whittaker M, Milligan RA, Downing KH. High-resolution model of the microtubule. Cell. 1999;96:79–88. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80961-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oosawa F, Asakura S. Thermodynamics of the Polymerization of Protein. Academic Press; London: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Parness J, Horwitz SB. Taxol binds to polymerized tubulin in vitro. J Cell Biol. 1981;91:479–487. doi: 10.1083/jcb.91.2.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pera B, Razzak M, Trigili C, Pineda O, Canales A, Buey RM, Jimenez-Barbero J, Northcote PT, Paterson I, Barasoain I, et al. Molecular Recognition of Peloruside A by Microtubules. The C24 Primary Alcohol is Essential for Biological Activity. Chembiochem. 2010;11:1669–1678. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201000294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pryor DE, O’Brate A, Bilcer G, Díaz JF, Wang Y, Kabaki M, Jung MK, Andreu JM, Ghosh AK, Giannakakou P, et al. The microtubule stabilizing agent laulimalide does not bind in the taxoid site, kills cells resistant to paclitaxel and epothilones, and may not require its epoxide moiety for activity. Biochemistry. 2002;41:9109–9115. doi: 10.1021/bi020211b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reese M, Sanchez-Pedregal VM, Kubicek K, Meiler J, Blommers MJJ, Griesinger C, Carlomagno T. Structural basis of the activity of the microtubule-stabilizing agent epothilone A studied by NMR spectroscopy in solution. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2007;46:1864–1868. doi: 10.1002/anie.200604505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Pedregal VM, Kubicek K, Meiler J, Lyothier I, Paterson I, Carlomagno T. The tubulin-bound conformation of discodermolide derived by NMR studies in solution supports a common pharmacophore model for epothilone and discodermolide. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2006;45:7388–7394. doi: 10.1002/anie.200602793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato B, Muramatsu H, Miyauchi M, Hori Y, Takase S, Hino M, Hashimoto S, Terano H. A new antimitotic substance, FR182877. I. Taxonomy, fermentation, isolation, physico-chemical properties and biological activities. J Antibiot (Tokyo) 2000;53:123–130. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.53.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuck P. Size-distribution analysis of macromolecules by sedimentation velocity ultracentrifugation and lamm equation modeling. Biophys J. 2000;78:1606–1619. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76713-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka J, Higa T. Zampanolide, a new cytotoxic macrolide from a marine sponge. Tetrahedron Letters. 1996;37:5535–5538. [Google Scholar]

- Wyman J, Gill SJ. Binding and Linkage: Functional Chemistry of Biological Molecules. University Science Books; Mill Valley, Ca: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Yang C, Barasoain I, Li X, Matesanz R, Liu R, Sharom FJ, Díaz JF, Fang W. Overcoming Tumor Drug Resistence Mediated by P-glycoprotein Overexpression with high affinity taxanes: A SAR study of C-2 Modified 7-Acyl-10-Deacetil Cephalomannines. Chem Med Chem. 2007;2:691–701. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200700002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zurwerra D, Gertsch J, Altmann KH. Synthesis of (−)-Dactylolide and 13-Desmethylene-(−)-dactylolide and Their Effects on Tubulin. Organic Letters. 2010;12:2302–2305. doi: 10.1021/ol100665m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.