Abstract

Vismodegib (GDC-0449), an orally bioavailable small molecule inhibitor of Hedgehog signaling, was recently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of basal cell carcinoma that is either metastatic or locally advanced in patients who are not candidates for surgical resection or radiation. Given the absence of previously defined effective drug therapy for this disease, approval was granted based primarily on outcome of a non-randomized parallel cohort phase II study of 99 patients with advanced basal cell carcinoma, with a primary endpoint of objective response rate. Response rates of 30.3 and 42.9 percent were observed in metastatic and locally advanced cohorts in this study, respectively, associated with median progression-free survival in both cohorts of 9.5 months. Ongoing clinical investigations include evaluation of the potential efficacy of vismodegib in a variety of disease contexts, and in combination with other agents. The mechanism of action, preclinical and clinical data, and potential utility in other disease contexts are reviewed.

Introduction

Vismodegib is the first targeted inhibitor of the Hedgehog signaling pathway to be approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. It is also the first agent of any class approved for the treatment of metastatic or locally advanced unresectable basal cell carcinoma (BCC). Its rapid path to market was based in large part on the strengths of a non-randomized pivotal 104 patient study with a primary endpoint of response rate. Data from this study were buttressed by substantial and supportive efficacy, safety, pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic data from other sources. This approval came almost precisely 5 years after the date of first human administration of vismodegib. The pathway to approval of vismodegib represents an interesting case study in the era of molecularly targeted drug development, and demonstrates the willingness of regulatory agencies to consider alternative registration strategies, beyond the traditional randomized phase III study focused on overall survival, in unusual circumstances and in rare disease contexts.

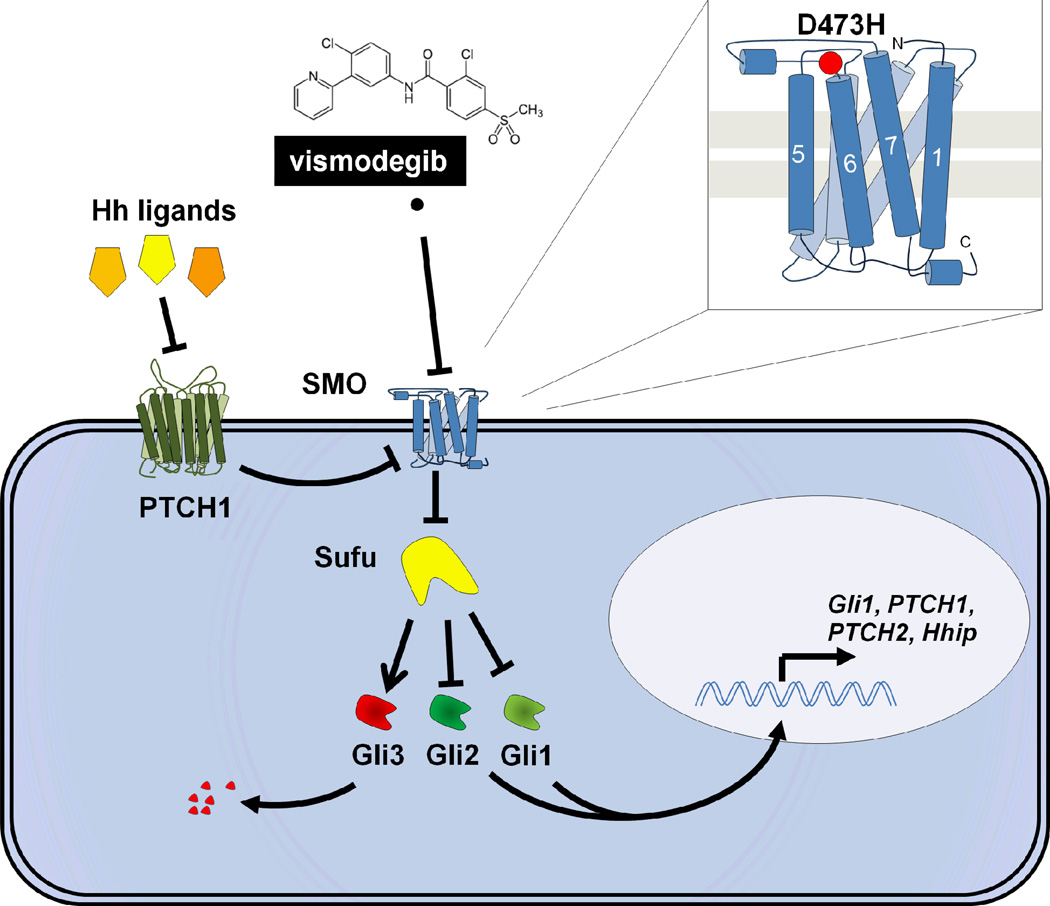

The Hedgehog pathway has been the subject of multiple recent reviews (e.g. (1)) and is outlined schematically in Figure 1; this CCR Drug Update will focus primarily on the clinical development of vismodegib, with brief reference to salient details of this particularly interesting signaling cascade.

Figure 1. Hedgehog signaling, vismodegib action, and acquired resistance.

The Hedgehog pathway is normally regulated through a cascade of primarily inhibitory signals. Any of 3 mammalian Hedgehog (Hh) ligands (Sonic, Indian, or Desert Hedgehog) bind to cell surface PTCH1. Ligand binding to PTCH1 relieves PTCH1 inhibition of the critical activator of Hedgehog signaling, SMO. PTCH1 deficiency, found in the majority of BCC and about 30% of medulloblastoma, is associated with constitutive, ligand-independent activation of SMO. In mammalian cells, derepression of SMO is associated with its translocation from internal vesicles to the cell membrane cilium (not shown). Active SMO signals downstream through an intermediary Sufu, promoting the release of Gli family transcription factors which can then translocate to the nucleus to affect gene transcription. There are multiple Gli proteins whose functions are somewhat cell type dependent; in general, Gli2 appears to be a particularly strong activator of downstream gene transcription (along with Gli1), while Gli3 is in most contexts inhibitory. Pathway activation and release from Sufu can lead to proteosomal degradation of Gli3, and to preferential nuclear translocation of Gli1 and Gli2, which activate transcription of multiple target genes, including key regulators of the Hedgehog pathway, notably Gli1 and PTCH1. Vismodegib binds to the extracellular domain of SMO, markedly inhibiting downstream signaling, even in the absence of PTCH1. The first documented mechanism of clinical acquired resistance to vismodegib is a secondary mutation in the extracellular domain of SMO, D473H (indicated in the inset as a red circle), which prevents vismodegib binding.

Hedgehog: From Pathway Discovery to Drug

The Hedgehog pathway was initially identified as a critical developmental regulator of embryonic segment polarity in Drosphila in 1980 (2). This and related developmental work in fly body patterning was recognized by the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1995. Vertebrate homologues of the Drosphila Hedgehog ligand were first reported in 1993, and definition of central components of the mammalian signaling pathway followed in the late 1990s and early 2000s (reviewed in (3)). The first definitive linkage of mutation in this pathway to cancer, i.e. to development of BCC, was made in 1996 (4, 5).

The first small molecule inhibitor of the Hedgehog pathway, the naturally occurring compound cyclopamine, was identified in 2000 (6). This discovery, together with rapidly accumulating evidence implicating the Hedgehog pathway in oncogenesis, led to focused efforts by multiple biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies to develop cyclopamine derivatives with improved pharmacologic properties, or to develop agents that effectively out-competed cyclopamine for binding to the critical cell surface activator of Hedgehog signaling, the 7-transmembrane G protein-coupled-like receptor, SMO.

Vismodegib is a member of this second class: structurally unrelated to cyclopamine but able to bind with high affinity and specificity to SMO, leading to potent suppression of Hedgehog signaling in reporter systems and in a preclinical model of Hedgehog-dependent disease (7). An Investigational New Drug application for vismodegib was filed with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in September 2006, leading to launch of a first-in-human phase I clinical trial at 3 U.S. sites in January 2007.

Focused Phase I Development

The first-in-human study of vismodegib employed a traditional 3+3 phase I dose escalation schema in patients with any advanced solid tumor, designed to define a maximally tolerated dose. We modified this initial plan based on two interesting early observations: one, this agent had strikingly unusual pharmacokinetic properties that obviated the need for continued dose escalation (summarized in the following section); and two, this agent had remarkable single-agent activity in a patient with widely metastatic BCC treated in the initial dose cohort.

Hedgehog signaling has been implicated in solid tumor biology through several mechanisms, including a paracrine pathway involving signaling between epithelial cancer cells and surrounding mesenchymal stromal cells (reflecting a common mode of Hedgehog signaling in normal embryonic development), and a role in maintenance of a putative tumor stem cell niche through autocrine signaling in a subset of cancer cells with high tumorigenic potential (reviewed in (1, 8)). In addition, there are two tumor types in which mutations in key regulatory components of the Hedgehog pathway result in markedly hyperactive, constitutive, ligand-independent signaling: BCC and medulloblastoma.

Advanced and surgically incurable BCC can occur spontaneously, or in association with an inherited genetic syndrome affecting the Hedgehog pathway, basal cell nevus syndrome (BCNS; discussed below) (9). One patient with advanced BCC was included in each of the 3 dose levels explored in phase I. After BCC responses were seen, the trial was amended to include expansion cohorts focusing on patients with advanced BCC. Of the 68 patients ultimately enrolled on this phase I study, 33 had locally advanced or metastatic BCC, and of these 33 BCC patients, objective responses were observed in 18 (10). Enrichment of the phase I trial to substantially oversample BCC patients provided both an important proof of principle regarding the single agent efficacy of this novel inhibitor, and an immediate framework for the subsequent phase II study supporting registration.

Unusual Pharmacokinetics

Three dose levels were explored in phase I: 150 mg, 270 mg, and 540 mg PO daily (11). Allometric scaling of preclinical animal models suggested estimates of vismodegib half-life in humans as short as 13.6 hours (12), and in fact the original phase I study design allowed for consideration of twice daily dosing. However, single dose administration followed by 7-day washout in patients revealed minimal decline in plasma drug concentrations between days 2 and 8, suggesting an exceptionally long terminal half life (13). Vismodegib is highly protein bound, and total drug levels closely parallel blood levels of alpha 1-acid glycoprotein (13). With continuous daily dosing, steady state plasma concentrations averaging 22 µM were achieved within 7 – 14 days independent of dose: indistinguishable levels of vismodegib were observed in all three dose cohorts (11). Based on the observed similar steady state plasma concentrations among initial dose cohorts, and the clear signal of biological efficacy, no further dose escalation has been explored. The lowest daily dose level tested, 150 mg, was suggested as the recommended phase II dose.

A subsequent detailed pharmacokinetic study explored the question of whether intermittent dosing could maintain similarly stable and high vismodegib concentrations following an 11-day “loading” period of 150 mg daily (14). However, compared to continuous daily dosing, thrice weekly and one weekly maintenance schedules of vismodegib were associated with 50% and 80% decreases in plasma levels of unbound drug, respectively, below threshold levels most effective in preclinical models, reinforcing the recommended phase II dose and schedule of 150 mg PO daily.

Registration Strategy: Phase II Development in Advanced BCC

Based on the observed responses in advanced BCC patients treated on the phase I protocol, and the lack of any standard of care therapies in this patient population, a multicenter phase II study was launched to document objective response rate in patients with advanced BCC (15). The phase II study enrolled advanced BCC patients in 2 cohorts: one with RECIST-measurable metastatic BCC (N = 33), and the other with locally advanced BCC considered inoperable or surgically inappropriate (N = 63). For the latter cohort, a composite endpoint for objective response that included measurable diameter and ulceration of visible tumors as well as RECIST criteria for localized but deeply invasive tumors was employed. For both cohorts, responses were assessed by centralized independent review.

The primary results of this study largely confirm, and extend, the data obtained in phase I. Objective responses were observed in 30% of patients in metastatic BCC, and in 43% of those with locally advanced disease (15). Thirteen patients with locally advanced disease (21%) experienced complete responses. Overall disease control rate (response plus disease stability) for the entire study population was over 86%. The response rates observed in both cohorts significantly exceeded the predefined criteria for study success, and supported the approval of vismodegib in the BCC disease categories defined in this study. However, the long term durability of these promising effects remains a concern: median duration of response in both cohorts was 7.6 months, and median progression-free survival 9.5 months (see Acquired Resistance, below).

Cancer Prevention: Inhibition of Tumor Formation in a High Risk Cohort

BCNS is caused by germline inactivating mutation of one copy of the PTCH1 gene, encoding the primary inhibitory regulator of the hedgehog pathway (Fig. 1). Inactivation of the second allele leads to tumorigenesis. BCNS patients commonly develop hundreds to thousands of BCCs over the course of their adult lives (9). A recent small but innovative study of 41 BCNS patients with substantial disease burden evaluated the effect of vismodegib vs. placebo in a 2:1 randomization, with a primary endpoint of reduction in new surgically eligible BCCs (16). Vismodegib significantly reduced the rate of new tumor formation, from 29 to 2.3 tumors per patient per year (p < 0.001). In addition, consistent with the larger phase II study above, responses in existing lesions was observed, including some complete regressions. These data suggest vismodegib may have a role as a cancer preventive agent, although this study does not definitively distinguish between prevention of tumor initiation, and delay in the appearance of clinically significant disease.

Toxicity

The Hedgehog pathway, while playing essential roles in embryonic development, appears minimally active in most adult tissues. Nonetheless, adverse events are experienced by patients on vismodegib, particularly with prolonged administration. Several of the most common toxicities appear to be class effects, seen consistently in early phase clinical studies of structurally diverse SMO inhibitors. Final reports of phase I studies of other SMO antagonists are not yet available but several have been publicly presented (17–19). Taken together these data suggest muscle spasms, alopecia, dysgeusia, nausea, and fatigue as common toxicities across the class.

In the phase II BCC registration study of vismodegib, muscle spasms or cramps were experienced by 68% of subjects; alopecia, 64%; dysgeusia, 51%; weight loss, 46%; and fatigue, 36%. Between 20 and 30% of patients experienced nausea, decreased appetite, or diarrhea. For all of these adverse effects, a large majority reported only grade 1 – 2 (mild - moderate) toxicity. Severe toxicity was rare and without evident consistency or pattern: only 4 severe adverse events considered to be possibly related to vismodegib, including one patient each with cholestasis, pulmonary embolus, dehydration/syncope, and cardiac failure with pneumonia. No deaths on study were attributable to vismodegib.

While the toxicities of vismodegib are generally mild, the chronic and persistent nature of these toxicities can limit patient willingness to stay on therapy. At the time of data cutoff for the definitive phase II study, 30% of patients with metastatic and 45% of patients with locally advanced BCC had discontinued vismodegib for reasons other than disease progression or death (15); similarly in the BCNS prevention study, 54% of patients on vismodegib discontinued therapy due to adverse events (16).

Acquired Resistance

Somatic mutations leading to constitutive activation of Hedgehog signaling and consequent dependence on the pathway are found in about a third of medulloblastoma cases. The phase I study of vismodegib included a single patient with widely metastatic PTCH1-mutant medulloblastoma, who experienced rapid tumor regression in all sites of disease (20). This dramatic improvement, however, was short-lived, followed by multifocal disease progression. Recurrent disease in this individual was associated with an acquired tumor-specific mutation in SMO that inhibited vismodegib binding to the protein (Fig.1, inset) (21).

BCC is a more indolent cancer than medulloblastoma, and the responses observed have been more durable. Nonetheless, the 9.5 month median progression-free survival observed in both locally advanced and metastatic BCC patients treated with vismodegib speaks to the need for continued research to define the mechanisms of acquired resistance, and to develop combinatorial strategies to improve the long-term prognosis of patients with this disease. A secondary SMO mutation has been identified in a progressive lesion from a BCC patient on vismodegib, suggesting that similar mechanisms of acquired resistance may apply to both BCC and medulloblastoma (unpublished).

Application in Other Diseases: Combination Therapies

Although BCC is the most common human malignancy, affecting over 2 million individuals in the U.S. annually, it is almost always surgically curable: metastatic BCC is a rare disease. Medulloblastoma, while the most common brain cancer in children, is also not a major cause of cancer mortality. There has been great interest in exploring the potential utility of vismodegib and other SMO inhibitors in patients with other diseases.

To date, no definitive clinical responses to SMO inhibitors have been reported in diseases other than BCC and medulloblastoma. Based on extensive preclinical data implicating Hedgehog signaling in tumor-stroma interactions, and in maintenance of tumor progenitor cell populations, several studies have been initiated combining vismodegib with standard cytotoxic therapies or other targeted agents for a wide range of malignancies. Results of most of these studies are not yet available. An initial 199 patient randomized phase II study evaluating first line cytotoxic therapies for colorectal cancer with vismodegib or placebo was disappointing, with no statistically significant differences in outcome between arms, and a hazard ratio for progression-free survival trending in favor of the control arm (22). Overall survival data for this study are not yet available.

Recent preclinical data strongly support a role for Hedgehog signaling in maintenance of tumorigenic capacity in small cell lung cancer (23). We recently completed accrual to a randomized phase II study evaluating standard first line chemotherapy for extensive stage small cell lung cancer alone, with vismodegib, or with another targeted agent (cixitumumab, targeting IGF-1R), with continuation of the investigational agents as maintenance therapy, through the Eastern Oncology Cooperative Group. Outcome data from this study are not yet available.

Conclusions and Future Directions

Vismodegib is a potent, selective, orally bioavailable Hedgehog antagonist. Its approval represents the latest in a series of success stories in rapid deployment of molecularly targeted anticancer agents based on a strategy of focusing early phase clinical development on molecularly defined subsets of patients. Vismodegib demonstrates remarkable activity against BCC, with recent studies supporting both therapeutic and preventive efficacy. Factors contributing to its exceptionally rapid progress from first-in-human testing to regulatory approval include an acceptable toxicity profile, early recognition of achievement of a biologically effective concentration in the first dose cohort explored, and an early phase development plan that focused on a disease strongly dependent on the pathway being targeted, and for which there was a clear unmet need.

Several questions and challenges remain. While categorized as mild to moderate, cumulative toxicity of this agent over time has led to discontinuation of therapy in a substantial fraction of patients. Chronic adverse effects will limit the potential utility of vismodegib as a preventive agent in any but the highest risk settings. Strategies to ameliorate some of the common toxicities of vismodegib will be important, and may improve the quality of life of patients receiving this, and similar, agents.

The median response duration of 7.6 months in advanced BCC patients responding to vismodegib underscores the need to consider strategies to treat, or prevent the emergence of, vismodegib-resistant disease. Essentially all Hedgehog inhibitors in clinical development bind the extracellular domain of SMO, and cross-resistance is likely. Notably in this context, although clearly anecdotal, we observed no responses in 7 advanced BCC patients who had previously progressed on vismodegib when treated with IPI-926, a similarly active SMO inhibitor (19). Agents targeting other critical nodes of the Hedgehog pathway, beyond SMO, are being actively pursued.

Medulloblastoma has peak incidence at age 5, a period of active bone growth and morphogenesis. Exposure of young animals to Hedgehog inhibition has been associated with permanent defects in skeletal development (24). Trials are ongoing to assess the feasibility and efficacy of administration of vismodegib in prepubescent children with this important disease.

Finally, despite multiple lines of preclinical evidence suggesting potential roles for Hedgehog signaling in common lethal cancers, early signals from studies combining SMO inhibitors with chemotherapy, or following chemotherapy as maintenance, have not yet shown clear evidence of benefit. Multiple such trials are in progress or recently completed, and results are eagerly awaited. Treating advanced BCC may prove to be the hedgehog’s One Big Thing (25); how much cooler if it turns out to address many things.

Acknowledgments

Grant Support: Burroughs Wellcome Clinical Scientist Award in Translational Research, and the Flight Attendant Medical Research Institute Center of Excellence.

Footnotes

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest: CMR has previously consulted for Genentech.

References

- 1.Ng JM, Curran T. The Hedgehog's tale: developing strategies for targeting cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:493–501. doi: 10.1038/nrc3079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nusslein-Volhard C, Wieschaus E. Mutations affecting segment number and polarity in Drosophila. Nature. 1980;287:795–801. doi: 10.1038/287795a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ingham PW, McMahon AP. Hedgehog signaling in animal development: paradigms and principles. Genes Dev. 2001;15:3059–3087. doi: 10.1101/gad.938601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hahn H, Wicking C, Zaphiropoulous PG, Gailani MR, Shanley S, Chidambaram A, et al. Mutations of the human homolog of Drosophila patched in the nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome. Cell. 1996;85:841–851. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81268-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson RL, Rothman AL, Xie J, Goodrich LV, Bare JW, Bonifas JM, et al. Human homolog of patched, a candidate gene for the basal cell nevus syndrome. Science. 1996;272:1668–1671. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5268.1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Taipale J, Chen JK, Cooper MK, Wang B, Mann RK, Milenkovic L, et al. Effects of oncogenic mutations in Smoothened and Patched can be reversed by cyclopamine. Nature. 2000;406:1005–1009. doi: 10.1038/35023008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robarge KD, Brunton SA, Castanedo GM, Cui Y, Dina MS, Goldsmith R, et al. GDC-0449-a potent inhibitor of the hedgehog pathway. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2009;19:5576–5581. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.08.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Merchant AA, Matsui W. Targeting Hedgehog--a cancer stem cell pathway. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:3130–3140. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Epstein EH. Basal cell carcinomas: attack of the hedgehog. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:743–754. doi: 10.1038/nrc2503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Von Hoff DD, LoRusso PM, Rudin CM, Reddy JC, Yauch RL, Tibes R, et al. Inhibition of the hedgehog pathway in advanced basal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1164–1172. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0905360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.LoRusso PM, Rudin CM, Reddy JC, Tibes R, Weiss GJ, Borad MJ, et al. Phase I trial of hedgehog pathway inhibitor vismodegib (GDC-0449) in patients with refractory, locally advanced or metastatic solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:2502–2511. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong H, Chen JZ, Chou B, Halladay JS, Kenny JR, La H, et al. Preclinical assessment of the absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion of GDC-0449 (2-chloro-N-(4-chloro-3-(pyridin-2-yl)phenyl)-4-(methylsulfonyl)benzamide), an orally bioavailable systemic Hedgehog signalling pathway inhibitor. Xenobiotica. 2009;39:850–861. doi: 10.3109/00498250903180289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graham RA, Lum BL, Cheeti S, Jin JY, Jorga K, Von Hoff DD, et al. Pharmacokinetics of hedgehog pathway inhibitor vismodegib (GDC-0449) in patients with locally advanced or metastatic solid tumors: the role of alpha-1-acid glycoprotein binding. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:2512–2520. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lorusso PM, Jimeno A, Dy G, Adjei A, Berlin J, Leichman L, et al. Pharmacokinetic dose-scheduling study of hedgehog pathway inhibitor vismodegib (GDC-0449) in patients with locally advanced or metastatic solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:5774–5782. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-0972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sekulic A, Migden MR, Oro AE, Dirix L, Lewis KD, Hainsworth JD, et al. Efficacy and safety of vismodegib in advanced basal cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2012 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113713. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tang JY, Mackay-Wiggan JM, Aszterbaum M, Yauch RL, Lindgren J, Chang K, et al. Inhibiting the hedgehog pathway in Basal Cell Nevus Syndrome patients. N Engl J Med. 2012 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1113538. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodon Ahnert J, Baselga J, Tawbi HA, Shou Y, Granvil C, Dey J, et al. A phase I dose-escalation study of LDE225, a smoothened (Smo) antagonist, in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:15s. (abstr 2500) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Siu LL, Papadopoulos K, Alberts SR, Kirchoff-Ross R, Vakkalagadda B, Lang L, et al. A first-in-human, phase I study of an oral hedgehog pathway antagonist, BMS-833923 (XL139), in subjects with advanced or metastatic solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2010;29:15s. (abstr 2501) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rudin CM, Jimeno A, Miller WH, Eigl BJ, Gettinger SN, Chang ALS, et al. A phase I study of IPI-926, a novel hedgehog pathway inhibitor, in patients with advanced or metastatic solid tumors. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29 (abstr 3014) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rudin CM, Hann CL, Laterra J, Yauch RL, Callahan CA, Fu L, et al. Treatment of medulloblastoma with hedgehog pathway inhibitor GDC-0449. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1173–1178. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0902903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yauch RL, Dijkgraaf GJ, Alicke B, Januario T, Ahn CP, Holcomb T, et al. Smoothened mutation confers resistance to a Hedgehog pathway inhibitor in medulloblastoma. Science. 2009;326:572–574. doi: 10.1126/science.1179386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berlin J, Bendell J, Hart LL, Firdaus I, Gore I, Hermann RC, et al. A phase 2, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of Hedgehog pathway inhibitor GDC-0449 in patients with previously untreated metastastic colorectal cancer. Ann Oncol. 2010;21:S8. (abstr LBA21) [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park KS, Martelotto LG, Peifer M, Sos ML, Karnezis AN, Mahjoub MR, et al. A crucial requirement for Hedgehog signaling in small cell lung cancer. Nat Med. 17:1504–1508. doi: 10.1038/nm.2473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kimura H, Ng JM, Curran T. Transient inhibition of the Hedgehog pathway in young mice causes permanent defects in bone structure. Cancer Cell. 2008;13:249–260. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Attributed to Achilochus. πόλλ' οἶδ' ἀλώπηξ, ἀλλ' ἐχῖνος ἓν μέγα (The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing). Circa 650 BCE