Summary

In multiple sclerosis, type I interferon (IFN) is considered immune-modulatory, and recombinant forms of IFN-β are the most prescribed treatment for this disease. This is in contrast to most other autoimmune disorders, since type I IFN contributes to the pathologies. Even within the relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) population, 30–50% of MS patients are nonresponsive to this treatment and it consistently worsens neuromyelitis optica (NMO), a disease similar to RRMS. In this article, we discuss the recent advances in the field of autoimmunity and introduce the theory explain how type I IFNs can be pro-inflammatory in disease that is predominantly driven by a Th17 response and are therapeutic when disease is predominantly Th1.

Keywords: interferon, Th17, Th1, autoimmunity, IL-7

Introduction

Type I interferons (type I IFNs) were first discovered by Isaacs and Lindenmann (1) when they observed that viral infected chick embryo cells produced a factor that interfered with subsequent viral infections. This cytokine family has expanded to include the IFN-α molecules, IFN-β, as well as the newly characterized IFN-ε, IFN-κ, IFN-τ, IFN-δ, and IFN–ζ (2). Interferons are integral in combating viral infections and tumors, and recombinant versions of type I IFN are used for treating hepatitis and melanomas (3, 4). But in autoimmune conditions, type I IFN has both beneficial and detrimental effects, depending on the disease context.

It is widely accepted that type I IFN is anti-inflammatory in the relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS) patient population (5). Recombinant IFN-β is most prescribed treatment for RRMS. In general, IFN-β is well tolerated and is thought to reduce relapse rate by 30%. But the most troublesome problem for IFN-β therapy is that up to 50% of RRMS patients do not respond to treatment, and in a subset of patients, this treatment might actually induce relapses.

In other autoimmune diseases, type I IFNs, including IFN-β, actually have inflammatory functions that contribute to disease symptoms; these diseases include systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), neuromyelitis optica (NMO), and psoriasis (6–10). Collectively, these observations demonstrate that type I IFN can either inhibit or promote autoimmunity and inflammation depending on the disease context. This review explores the recent research advances in the field of autoimmunity to gain an understanding of why type I IFN is anti-inflammatory and therapeutic in some diseases and pro-inflammatory and pathogenic in others.

IFN-β treatment in RRMS

In RRMS, it is widely accepted that type I IFN is anti-inflammatory to the general RRMS patient population (5). IFN-β is the most widely prescribed treatment for MS and clinicians now prescribe one of the four available interferons on the market (Avonex, Biogen Idec; Rebif, Merck Serono; Betaferon, Bayer; and Extavia, Novartis) when the patient is first diagnosed (11). In general, IFN-β therapy is well tolerated and reduces the relapse rate by 30% in patients with RRMS. In fact, there are some patients for whom this treatment works exceptionally well, and they remain relapse free for several years while on this treatment. A common side effect of IFN-β therapy is moderate to severe flu-like symptoms. In some severe cases, IFN-β can cause liver damage that requires the patients to either reduce the dose or change to an alternative therapy such as glatiramer acetate (12). The biggest drawback with IFN-β therapy is that up to 50% of MS patients do not respond to treatment. There has recently been a major research effort to determine biomarkers that can identify responders and non-responders prior to or shortly after the initiation of IFN-β therapy (13–16). This would eliminate the treatment of individuals who would have no benefit from this expensive drug.

Mode of action of IFN-β: insights from EAE

The mode of action of IFN-β treatment of RRMS is unclear, and there still is no definitive predictive marker to establish responsiveness to treatment. Tackling these biological questions is a formidable task. Obtaining tissues samples taken at various stages of disease from a sizable patient population with extensive recorded clinical histories is very rare. In addition, the specimens taken from these cohorts are usually limited to serum or plasma and not from the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), which is anatomically adjacent to the active lesions. Furthermore, the experimental approaches to human diseases outside of clinical trials are very much observational and many consider these as stamp collecting exercises. There is a growing amount of evidence that strongly suggests that RRMS symptoms are initiated by a T-helper (Th) cell response to myelin in the central nervous system (CNS). First, the human leukocyte antigen-DR (HLA-DR) locus, which encodes for the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class II molecule, has the strongest genetic association with RRMS (17). Secondly, many studies have identified CD4+ T cells in both the spinal fluid and in brain lesions from MS patients (18). Moreover, animal models of MS, collectively called experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), have similar pathological features of RRMS that are initiated by T-helper cells (19). Given the obstacles for conducting research directly on RRMS experiments with EAE, primarily done with mice, have been an effective way to model this disease and to study the mode of action for IFN-β therapy.

Experiments using type I IFN to treat EAE date back to 1982, where researchers demonstrated that injection of recombinant IFN-β suppressed demyelination in mice immunized with myelin antigens in complete Freund’s adjuvant (20). Later, other studies confirmed the inhibitory effects of IFN-β in EAE using IFN-β knockout mice (21). More recently, two sets of experiments described a potential mechanism by which type I IFN inhibits neuro-autoimmunity. One publication by Prinz et al. (22) demonstrates that the local production of endogenous IFN-β is elevated in the CNS during EAE. These researchers created a panel of conditional type I IFN receptor (IFNAR) knockout mice. They found that mice with myeloid cells deficient in IFNAR had increased disease symptoms compared to control animals, while disease was not significantly altered in mice deficient in IFNAR in T cells, B cells, or neurons. Also, they discovered that the myeloid cells from these conditional knockouts had increased expression of pro-inflammatory chemokines, suggesting that type I IFN attenuates CNS inflammation by inhibiting the ability of macrophages and microglia cells to produce chemokines. In another related study, Guo et al. (23) also examined the how endogenous type I IFN signaling affects EAE. They too demonstrated that IFNAR deficiency resulted in defective myeloid cell function. But in contrast to Prinz et al., they concluded that the anti-inflammatory effects of type I IFN was due to the elevation IL-27 which subsequently inhibits the differentiation of the inflammatory Th17 cells. In spite of the differences in these two publications, these researchers independently describe that endogenously expressed type I IFN suppresses inflammation and autoimmunity in the CNS by acting on cells in the myeloid lineage. However, the myeloid lineage is comprised of many functionally different cell types such as macrophages, microglia, dendritic cells, and granulocytes, and thus, the specific target cell for IFN-β therapy remains to be elucidated.

Prinz (22) and Guo (23) have begun to elucidate the effects endogenous type I IFN play in neuro-autoimmunity. Other studies have used EAE to show how IFN-β as a treatment inhibits disease symptoms. Two studies have used a model of EAE that requires immunization of mice with myelin antigens in complete Freund’s adjuvant to assess the effects of IFN-β treatment (21, 24). These experiments demonstrated that IFN-β treatment reduced EAE symptoms, and this treatment effect was correlated with decreased amounts of both Th17 and Th1 cells and induction of Th2 and regulatory T cells.

Th1 and Th17 pathways determine response to IFN-β in EAE

Several different classifications of effector T helper cells have been presented: Th1, Th2, Th3, Th9, and Tfh (25–27). Here we discuss the three major subsets, Th1, Th2 and Th17. These subsets have been classified based on their function in immunity and by the cytokines they produce. The Th1 subset is involved in antiviral immunity and is driven by IL-12 to secrete IL-2, IFN-γ, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and is involved in antiviral immunity. Th2, driven by IL-4, produce IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 and is essential for clearing parasites. The relatively new Th17 subset develops in the presence of IL-6, transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β), and IL-23 and secretes IL-17A, IL-17F, and IL-22 and defends against bacterial and fungal infection (28).

RRMS and EAE were originally thought to be Th1-mediated diseases. IFN-γ was found in the CSF of patients with MS and spinal cords from mice with EAE (29). Mice deficient in T-bet, an essential Th1 transcription factor, are resistant to EAE (30). Mice given myelin-specific Th1 cells develop severe EAE symptoms (13, 31). Finally, IFN-γ treatment of RRMS patients induced severe relapses (32).

However, confounding data using the EAE model showed that treatment with IFN-γ reversed paralysis, and blockade of IFN-γ and IL-12 worsened disease in mice (33). This observation led to the discovery of the Th17/IL-23 pathway. Since the Th17 pathway is strongly inhibited by IFN-γ (34) and deletion of IL-23 protects mice from EAE (35), Th17 overtook Th1 as the inflammatory Th cells in neuro-inflammation. Since then, several papers have disputed the predominance of Th17 in causing inflammation in EAE and MS (36, 37). Transcriptional and fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analyses demonstrated that Th1 and Th17 cells are present in brain lesions and in blood of MS patients (38, 39). It has been demonstrated that both the Th1 and Th17 cells are capable of inducing EAE symptoms in mice (13, 31, 40). Therefore, it is generally accepted that both Th1 and Th17 cells are inflammatory in EAE, and many researchers now feel that these cells play a major role in the pathogenesis of MS.

Studies by several by independent researchers have indicated that type I IFN can inhibit Th1 and Th17 functions in cell culture experiments using human and mouse tissue (34, 38, 41, 42). It could be concluded that both Th1-driven and Th17-driven autoimmunity would be attenuated by IFN-β therapy. In our own publication in 2010, we also conducted T-cell culture assays to determine how IFN-β treatment alters Th cell differentiation (13). In concordance with Guo et al. (23), we found that in Th1 conditions, IFN-β directly induced IL-27 in antigen-presenting cells, which subsequently led to the elevation of IL-10 in the Th1 cells. In addition, we observed that IFN-β potently inhibited Th17 differentiation in culture.

Based on our in vitro experiments and those done by others, it could be concluded that IFN-β has the potential to be anti-inflammatory in both Th1 and Th17 driven EAE. To directly test this hypothesis, we administered recombinant mouse IFN-β to mice with EAE induced by the transfer of either myelin-peptide specific Th1 or Th17 cells (13). IFN-β treatment effectively reduced disease symptoms in mice with EAE induced with Th1 cells. In congruence with our cell culture experiments, IFN-β increased the amount of IL-10 made by splenocytes from mice with Th1 EAE. Unexpectedly in Th17-induced EAE, we observed that IFN-β therapy worsened disease symptoms in mice.

This observation that Th17 EAE was exacerbated with IFN-β treatment was very surprising. A popular theory on the mode of action of IFN-β therapy is that it inhibits the Th17 differentiation to attenuate disease (38, 43). In fact, our in vitro and in vivo EAE experiments showed that IFN-β did inhibit IL-17 production in T cells (13). Yet, this treatment actually worsened Th17-induced disease. The reason why Th17 auto-immunity is exacerbated by type I IFN is not currently known, but we discuss possible mechanisms below.

Determining response to IFN-β therapy in RRMS patients

The clinical trials that led to the approval of IFN-β in RRMS patients indicated that some individuals experience clinical breakthrough from treatment, which means that they did not respond to well to the treatment (16). There could be many reasons why these patients did not respond to IFN-β therapy (reviewed in 44). Some of the postulated mechanisms are a decrease in IFNAR expression or decreased expression of signal transducer and activator of transcription 1 (STAT1) and STAT2, transcription factors activated by type I IFN. Another theory speculates that there is an increase in the suppressor of cytokine signaling (SOCS) proteins, which inhibit type I IFN signaling. These are very interesting and plausible reasons for non-responsiveness to treatment, but there has not been any clinical data to support these hypotheses.

Non-responsiveness could be explained by the theory that these patients have poor bioavailability of IFN-β. One well known theory for the decreased bioavailability is the development of antibodies to IFN-β (45). Several studies have identified that in some non-responders repeated injections of recombinant IFN-β elicits an antibody response against the cytokine, and in theory, these antibodies neutralize IFN-β’s beneficial effects (46–48). However, there are studies showing that the development of anti-IFN-β antibodies has no effect on the clinical outcome of the treatment (49). This demonstrates that there is still much to be learned about anti-IFN-β antibodies in MS treatment. Other biomarkers have been shown experimentally to have utility for the determination of IFN-β responsiveness. These include a bioassay for antiviral cytopathic effects and molecular assays (50), such as measuring the inducible expression of the IFN-inducible genes like myxovirus resistance 1 (MxA)(51).

Another intriguing hypothesis that has been supported by experimental data is that IFN-β non-responders have elevated levels of endogenous type I IFN prior to treatment. Comabella and colleagues (14) found that myeloid cells from the blood of non-responders had elevated STAT1 phosphorylation and expression of IFN-inducible genes. They also found that type I IFN itself was elevated in the serum of the patients. This demonstrates that type I IFN signaling is already activated in these non-responders prior to the initiation of IFN-β therapy. It can be speculated that the non-responders displaying upregulated type I IFN is an attempt by the body to counteract the inflammation. Since type I IFN expression is already high, administering more in the form of IFN-β treatment would be ineffective. Yet, Comabella et al. (14) proposed that the endogenous type I IFN actually drives the pro-inflammatory effects in these patients, similar to what is seen in systemic lupus erythematosus (10). For this reason, IFN-β treatment would be ineffective in these patients and it would likely worsen symptoms.

Other researchers have also come to the conclusion that IFN-β may play a direct role in inducing inflammation in non-responders. Rani et al. (52) show that the population of RRMS patients has a varied molecular response to IFN-β treatment, where even ‘non-responders’ show transcriptional activity after IFN-β treatment. In a follow up paper, this research group actually found that patients classified as ‘poor responders’ had an ‘excessive’ transcriptional response after IFN-β treatment, which was also qualitatively different from that of the ‘good-responders’ (53). These data provide more support for theory that type I IFN contributes to the disease process in non-responders.

In our exploratory biomarker study of 26 RRMS patients, 12 responders and 14 non-responders, we discovered a subset of non-responders that had high serum concentrations of IL-17F (a Th17 cytokine) prior to the initiation of IFN-β therapy (13). Th17 cells from both humans and mice produce high levels of IL-17F, which suggests that this group of non-responders had a Th17-driven pathology (13, 36). It should be noted that there are many other cell types, including neutrophils, macrophages, natural killer T (NKT) cells and others, that can produce Th17 cytokines (54, 55). In addition to IL-17F, these non-responders also had elevated levels of endogenous IFN-β compared to responders. In fact we found that the patients with high serum IL-17F were the patients who also had high IFN-β concentrations in the serum. This association suggests that there is a there is a biological link between these two cytokines. This observation is congruent with our experiments that demonstrate that mice with Th17 EAE do not respond to IFN-β treatment (13). It is also congruent with data from Comabella et al. (14) who demonstrate that type I IFN is elevated in non-responders prior to IFN-β treatment.

Since our publication in 2010, we have been a part of two collaborations: one with Biogen Idec and the other with Bayer pharmaceuticals. Both pharmaceutical companies have a large collection serum specimens taken from patients enrolled in clinical trials for Avonex and Betaseron. One aspect of this collaboration was to confirm or refute our initial IL-17F results. The results from the Bayer collaboration are concordant with our initial observation. Although differences in IL-17F levels were not statistically significant in responders and non-responders, the patients with very high IL-17F levels were non-responsive to Betaferon. Responding patients were defined by either as having no clinical relapses or no new magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) gadolinium-enhancing lesions while on treatment (unpublished data, manuscript in preparation). In the Biogen Idec collaboration, the measurements from our original sample set were independently validated, but their larger cohort did not confirm that elevated IL-17F is associated with non-responsive to Avonex (manuscript in press in the Journal of Neurology). In this study, responsiveness to treatment was based only upon clinical evaluation of the patients and not by MRI. In addition, patients that developed neutralizing antibodies to therapy were excluded (patients with neutralizing antibodies were included in the Bayer cohort and in our initial study). So, there are conflicting results from Bayer with Betaseron and Biogen with Avonex regarding elevated levels of IL-17F in non-responders. There are four differing aspects of these two larger studies: (i) The definition of responders and non-responders. Bayer used MRI to assess responsiveness, whereas Biogen Idec used clinically defined relapses. (ii) The Biogen study excluded patients that developed antibodies to IFN-β, whereas the Bayer study included those patients. (iii) Avonex and Betaseron are different formulations of IFN-β. Avonex is IFN-β1a and is a recombinant protein made in mammalian cells. Bayer is IFN-β1b and is produced in E. coli. (iv) The dosing of Avonex and Betaseron differ. Avonex is 30 micrograms of IFN-β given once per week intramuscularly. Betaseron is 250 micrograms of IFN-β given every other day subcutaneously. These differing aspects could account for the discordant results with IL-17F non-responders and further studies will be needed to address all of these issues.

Both type I and type II IFNs have been shown to directly inhibit IL-17A production and Th17 differentiation(34). In fact, two studies have shown that IFN-β treatment has been shown to inhibit IL-17A production from CD4+ T cells from RRMS patients (38, 43). The authors conclude that this is the therapeutic mechanism of IFN-β in RRMS. In our in vitro and in vivo experiments, we also found that IFN-β decreases IL-17A in mice (13). Therefore, this appears to contradict our hypothesis that type I IFN and IFN-β treatment exacerbates Th17 induced inflammation. Nevertheless, we find that IFN-β and IL-17F are both elevated in non-responders and that Th17 EAE is exacerbated by IFN-β. These data provide strong evidence that type I IFN drives inflammation in a Th17-induced disease. This phenomenon, where type I IFNs promote diseases predominantly driven by Th17, also occurs in other human autoimmune diseases.

Role of Type I IFN in other autoimmune diseases

Systemic lupus erythematosus

SLE is a highly variable autoimmune disease that may affect the skin, joints, kidneys, brain, and other organs. Currently, very few biological therapeutics have shown efficacy in this disease. Most recently, belimumab, an anti-BAFF antibody, has received US Food and Drug Administration approval and is now commercially available (56). Several decades ago it first was demonstrated that patients with SLE had increased type I interferon activity in their serum (57). More recently, gene expression technologies have demonstrated that hundreds of type I IFN-inducible genes are active in PBMCs from SLE patients (10), demonstrating that this disease has a type I IFN signature. Genetic data also supports this theory. Outside of HLA, genes in the type I IFN pathway are highly associated with SLE risk (58–61). There is also direct evidence that type I IFN plays a pathogenic role in this disease. Animal models of lupus have shown that blockade of type I IFN reduces symptoms (62, 63), and conversely treatment with type I IFN worsens disease (64, 65). These preclinical studies have led to a phase 1 clinical trial using a monoclonal antibody to IFN-α (66). Data from this trial are promising and show that this treatment reduces the type I IFN signature in SLE patients (67).

Th17 cells have also been implicated in the pathogenesis of SLE. The frequencies of Th17 cells as well as levels of IL-17A and IL-17F are elevated in blood from SLE patients (68). The associated granulocyte molecules, which are induced by Th17 cytokines, are also activated in lupus (10, 61). Furthermore, blockade of IL-17 and IL-23 inhibits SLE symptoms in mouse models. In the clinic, IL-6, a cytokine in the Th17 pathway, is a drug target with great potential in SLE. IL-6 is involved in a positive feedback loop with Th17. IL-6 is critical for the differentiation of Th17 cells (69) and the expression of IL-6 is driven by IL-17 signaling (70, 71). Tocilizumab, an anti-IL-6 antibody, is a drug that is showing promise in a small clinical trial in SLE where it decreased autoantibody levels and overall disease activity (72). Currently, there are no other Th17 cytokine blockers in clinical trials for SLE. Still, there is a case report of a patient with sub-acute lupus erythematosus who was successfully treated with ustekinumab (an IL-23 blocking antibody), and this drug may be another potential candidate for SLE therapy (73).

Neuromyelitis optica

NMO is a neuro-inflammatory disease that has many similarities to MS and at one time was considered a variant of RRMS. NMO is characterized by the presence of severe inflammation in the spinal cord and optic nerves (74). Lesions are also found in the brain of 60–70% of patients(75, 76), but MRI imaging demonstrates that they are not consistent with the Barkhof/Tintore criteria for RRMS diagnosis (16, 77). In addition, antibodies against aquaporin 4 (AQP4) are present in 80–90% of NMO, and the presence of AQP4-Ig is one clinical feature that is used to distinguish NMO from RRMS (47).

Another striking difference in NMO to RRMS is that NMO lesions have an abundance of infiltrating granulocytes, including both eosinophils and neutrophils, which are rarely seen in RRMS (74). In NMO, IL-17, IL-6, and the granulocyte chemo-attractant, IL-8/CXCL8, are elevated in the CSF compared to RRMS (78, 79). The frequency of Th17 cells in the blood is elevated in NMO compared to RRMS (80). IL-17 signaling is known to upregulate chemokines that recruit and activate granulocytes (40, 81, 82). Therefore, the high levels of IL-17 in the CNS of NMO patients are likely to induce the local expression of chemokines that recruit granulocytes to the CNS. In addition, we have recently published that NMO patients have elevated serum levels of the Th17 cytokines (IL-17A and IL-17F), the neutrophil chemo-attractants (CXCL5 and CXCL8), and neutrophil proteases, which further supports the hypothesis that the Th17/granulocyte axis is contributing to the pathology of this disease (in press in the Multiple Sclerosis Journal). In contrast, the majority of RRMS, except for a subset of IFN-β non-responders, may resemble a Th1-driven demyelinating disease.

In addition to Th17 and granulocytes, type I IFN has also been implicated as an important mediator of NMO pathology. Since NMO was at one time considered a version of MS, it was logical at the time to try IFN-β treatment in this disease. However, clinical trials of IFN-β therapy for NMO showed no therapeutic benefit (9), and in fact, several case reports have demonstrated that IFN-β treatment can induce severe relapses and exacerbations in this disease (8, 83, 84). A recent study also described that NMO has elevated interferon signature compared to RRMS (85). The elevated granulocyte signature and interferon signature in NMO reflect what is seen in SLE (10, 85). There are many cases in which NMO patients develop anti-nuclear antibodies (ANA) and can have co-morbidities with SLE (74, 86). In contrast, there are rarely any associations with RRMS and ANA or SLE co-morbidities.

Psoriasis

Psoriasis is another autoimmune disease where type I IFN and Th17 appears to drive pathology. This synergy between Th17 and type I IFN in psoriasis has been shown in mouse experiments (87). In this disease, it is thought that autoreactive T cells initiate chronic inflammation and cause the abnormal proliferation of keratinocytes to form psoriatic lesions and in some cases cause psoriatic arthritis. The IL-23/Th17 pathway has been implicated in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. Genetic studies have identified that polymorphisms in the IL-23/12p40 and IL-23R are risk factors for developing psoriasis (88, 89). In mice intradermal injections of IL-23 induce inflammation in the epidermis which resembles psoriasis (90). Moreover, ustekinumab, a monoclonal antibody (mAb) therapy that blocks IL-23 signaling, had success in clinical trials of psoriasis (91). Ustekinumab is now on the market to treat moderate to severe cases of this disease. Interestingly, this same treatment failed in RRMS, and this suggests that the majority of the RRMS population is not driven by the IL-23/Th17 pathway (92). Other Th17 cytokines have been found in psoriatic lesions, including IL-17A, IL-22, IL-8, and IL-17F (93, 94). In addition, results from advanced clinical trials using neutralizing antibodies to IL-17A mAb is showing efficacy as a treatment for psoriasis (95).

There is strong evidence that type I IFN has an important role in initiating inflammation in psoriasis. Like SLE and NMO, the type I IFN transcriptional signature is activated within the psoriatic plaques (96). Studies have shown that plasmacytoid dendritic cells (pDCs) are found in high numbers in pre-psoriatic plaque areas (6). pDCs are known for producing large quantities of type I IFN (97). Therefore, it is thought that pDCs are recruited to the pre-plaque area and secrete large quantities of IFN-β and IFN-α to perpetuate the inflammatory response. Experimental models have shown that blocking type I IFN signaling reduces psoriatic symptoms in animals (98). Several cases of psoriasis have developed after type I IFN was administered to treat RRMS and hepatitis, which is the most convincing evidence that type I IFN promotes psoriasis (99–104).

Ulcerative colitis

Trials with IFN-β and other type I IFNs have shown some efficacy in ulcerative colitis (UC)(105), but endpoints for the phase II clinical trials using Avonex for UC did not reach statistical significance (106). However, investigators at the US National Institutes of Health conducted a small study to assess the biological differences between UC patients who had responded well to IFN-β compared to patients who did not respond (107). Their observation was strikingly similar to our data in mice and RRMS (13). They observed that those patients who were non-responders to IFN-β had significantly greater Th17 population in the blood and lamina propria compared to responders.

How does Type I IFN exacerbate autoimmune diseases?

The mechanism by which IFN-β promotes symptoms in Th17 driven autoimmune diseases is currently unknown. However, several studies have reported many effects that could contribute to this phenomenon (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Potential mechanisms of how type IFN exacerbates autoimmune diseases.

Autoimmune diseases initiated with the IL-23/Th17 response secrete high levels of IL-17A and IL-17F. IL-17A and IL-17F initiate granulocyte infiltration to the site of inflammation as well as orchestrate germinal center formation and B-cell maturation in lymphoid tissues. Endogenously expressed or therapeutically administered IFN-β could exacerbate Th17 diseases by directly stimulating granulocytes to release tissue destructive proteases and cytokines or by elevating BAFF to enhance the production of autoreactive antibodies and memory B-cells. Type I IFN also upregulates IL-22 receptor on skin epithelial cells in psoriatic skin and BBB endothelium in NMO. IL-22 can contribute to inflammation by promoting the release of defensins and breaking down tight junctions at the BBB.

Type I IFN has a pro-inflammatory effect on granulocytes, which are commonly found in Th17 driven pathologies. It has been stimulates neutrophils to release neutrophil extracellular traps (NETS)(108), and we recently found that that IFN-β does as well (manuscript in press). These NETS have destructive proteases such as neutrophil elastase and cytokines that would promote inflammation and destroy inflamed tissues(109).

B cells could be affected by type I IFN to exacerbate symptoms. The B-cell-stimulating cytokine BAFF is known to be induced by type I IFN (110–112). Levels of BAFF are found to be elevated in SLE and NMO, and these increases have been attributed to the IFN signature in these diseases (113, 114). In line with this, MS patients also have elevated levels of BAFF after IFN-β therapy (110). BAFF functions to promote B-cell development, survival, and differentiation to plasma cells (115). Recently, it has been shown that IL-17 from Th cells plays an important role in autoantibody production by promoting the formation of germinal centers (116, 117). Therefore, in Th17 driven diseases, elevated BAFF induced by type I IFN would synergize with IL-17 to produce a robust autoreactive B-cells response, increase the production of autoantibodies and exacerbate diseases such as SLE and NMO.

Signaling from other Th17 cytokines, other than IL-17A and IL-17F, could be augmented by type I IFN. Recently, it has been shown that the receptor for IL-22, a cytokine produce by Th17 cells (25), is elevated in epidermis of psoriasis lesions compared to normal controls (118). Furthermore, they demonstrated IFN-α induces the expression of IL-22R on epidermal keratinocytes in culture (119). This IFN-induced increase in IL-22 signaling may lead to increased defensin and complement expression in leukocytes and epithelial cells in psoriasis and also contribute to the breakdown of the blood brain barrier in NMO (120–122).

How does IFN-β attenuate RRMS?

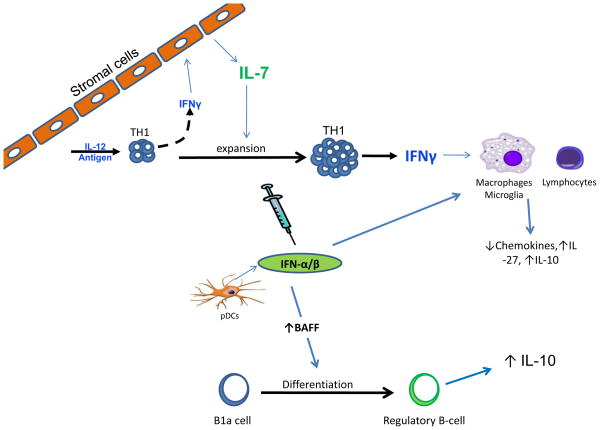

As we discussed earlier in this review, two recent articles demonstrated that modulating cytokine and chemokine expression in monocytes and macrophages is an anti-inflammatory property of type I IFN (22, 23). Currently, we do not fully understand the mode of action of IFN-β therapy, but there are many studies in the literature that provide alternative theories (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Potential mechanisms on how type I IFN protects in RRMS.

Autoimmune diseases initiated by Th1 cells have high levels of IFN-γ that drive lymphocytic and macrophage infiltration in to sites of inflammation. IFN-γ upregulates IL-7 expression in lymphoid tissue stromal cells during T-cell differentiation and provides signals to expand and maintain the Th1 population. IFN-β treatment synergizes with both IFN-γ and IL-7 to attenuate inflammation by upregulating the anti-inflammatory cytokines, IL-27 and IL-10, and decrease chemokine production from macrophages/microglial cells. Type I IFN also induces BAFF expression. BAFF then could directly or indirectly induce the differentiation of IL-10-producing regulatory B cells.

It has been speculated for some time that MS is caused by a viral infection (123); therefore, IFN-β could attenuate disease by clearing the virus. However, IFN-β successfully treats EAE (13, 20, 21, 24), a non-viral model of this disease. So, the antiviral effects of IFN-β may not be as essential as its anti-inflammatory properties. Several reports have identified potential anti-inflammatory functions that may contribute to the efficacy of IFN-β treatment. These include blockade of lymphocytes trafficking to the CNS, inhibiting metalloproteinase expression, increasing levels of soluble adhesion molecules in blood, reducing expression of MHC class II molecules, attenuating T-cell proliferation, and altering the cytokine milieu from pro-inflammatory to anti-inflammatory (44).

One fascinating alternative hypothesis suggests that the therapeutic mechanism of IFN-β is very similar to the new oral MS drug fingolimod (Gilenya, Novartis)(124, 125). Shiow et al. (125) demonstrated that type I IFN upregulates CD69 expression on CD4+ T cells during an immune response. They show that CD69 associates with and inhibits the function of the sphingosine 1 phosphate receptor (S1P1), the receptor targeted by fingolimod (124). Blocking S1P1 traps lymphocytes in lymphoid organs, preventing them from circulating and infiltrating into target tissues such as the MS brain.

Another interesting hypothesis is that the elevation in BAFF levels by IFN-β treatment could contribute to its therapeutic effects. Inhibition of BAFF has been shown to be effective in treating SLE and is currently one of the few drugs on the market for this disease (56). Data from a recent clinical trial showed that atacicept, a BAFF blocker, exacerbated symptoms in RRMS (126), and BAFF-deficient mice get worse EAE (127). This provides direct evidence that BAFF is anti-inflammatory in RRMS, and it is speculated that it is inducing a regulatory B-cell population (128). It has been shown that IFN-β treatment increases BAFF levels in RRMS patients (110), and furthermore, type I IFN has been shown to induce regulatory B cells in a mouse model of sepsis (129). Therefore, it is conceivable that BAFF maybe an important molecule for effective IFN-β therapy.

The suppressive effects of IFN-β have been attributed to the activation of the transcription factor ISGF3, which is a complex that is comprised of STAT1, STAT2, and IRF9 and binds to interferon stimulatory response elements (IRSE)(130). Yet, IFN-β can also induce the activation of other STATs (131, 132). The pathways activated by IFN-β depend on the relative concentrations of the STAT molecules within the cell and other cytokines and factors can have an influence on type I IFN signaling (133–135). Our mouse studies demonstrated that Th1 pathways are critical for the anti-inflammatory effect of IFN-β (13). Inhibition of EAE symptoms by IFN-β treatment requires IFN-γ, which is produced by autoreactive Th1 cells. We also published that IFN-β requires IFN-γ signaling to induce a sustained STAT1 response (13), but we recently have found that STAT4 activation is not affected by IFN-γ deficiency (unpublished observation). This is a noteworthy observation. STAT4 is essential for the induction of EAE (136), but STAT1 has anti-inflammatory effects in EAE, since mice deficient in STAT1 have exacerbated disease (30). Thus, the balance of the STAT1-STAT4 signaling induced by IFN-β could dictate the pro- or anti- inflammatory effects of this therapy.

These experiments showed that Th1 pathways are critical for the anti-inflammatory effect of IFN-β in mouse. However, this phenomenon is not obvious when we assessed biomarkers that correlate with a favorable response in RRMS patients. In our recent study (137), we found that serum levels of IL-7 are inversely correlated with IL-17F in RRMS patients. Moreover, high levels of IL-7 prior to treatment were associated with a good response to IFN-β therapy. In the past few years, several independent collaborations around the world identified that the IL-7 receptor gene has polymorphisms that confer a risk for developing RRMS (138, 139). In addition, expression of both IL-7R and IL-7 mRNA are significantly greater in the CSF of MS patients compared to patients with non-inflammatory neurological diseases (139). IL-7 signaling is critical in T-cell development and for the homeostasis of naive and memory T cells (140–142). Therefore, some researchers have concluded that IL-7 is a contributing factor for the progression of RRMS symptoms. This hypothesis was supported by mouse models. We and others (137, 143) have demonstrated that recombinant IL-7 treatment exacerbates EAE, and conversely, blocking IL-7 signaling with neutralizing antibodies or genetic deletions reverses EAE symptoms.

Our observation that high levels of IL-7 predicts a good response to IFN-β therapy does not appear to support our hypothesis that Th1 driven diseases respond favorably to this treatment (137). Furthermore, our hypothesis came under even more scrutiny, since it was reported that IL-7 aids in the differentiation of Th17 cells and not Th1 cells (143). However, in our experiments, we found that IL-7 has no effect on Th17 differentiation and actually promotes Th1 differentiation, even in the absence of IL-12 (137). Other studies have corroborated our results. Davis et al. (144) showed that culturing cord blood T cells with IL-7 promotes the survival and expansion of IFN-γsecreting Th1 cells. The biological relationships between Th1, IFN-γ, and IL-7 have also been demonstrated. First, IFN-γ directly induces the transcription of IL-7 in stromal cells (145, 146). Secondly, IL-7 is a critical factor for anti-viral immunity, the main function of the Th1 immune pathway (147). It is possible that together IFN-γ and IL-7 are involved in a positive feedback loop to maintain a Th1 immune response. We are currently identifying how this IL-7/Th1 axis is linked to a favorable response to IFN-β treatment. We have preliminary data demonstrating that IFN-β synergizes with both IFN-γ and IL-7 to upregulate IL-27 in macrophages, which in turn upregulates IL-10 (unpublished observation). The upregulation of IL-10 could then decrease chemokine/cytokine production from macrophages/microglial cells as observed by Prinz and Guo (22, 23). This synergy with IL-7 and IFN-β has been seen also in studies of human immunodeficiency virus. It is now speculated that the combination of IL-7 and IFN-β could be in full or in part responsible for the lymphopenia in HIV patients (133).

The biology of IL-7 signaling in MS is complex and is likely to be quite important in the pathophysiology of MS. To date, MS is the only autoimmune disorder where IL-7 signaling has been linked in genome-wide association studies (148). Furthermore, preclinical EAE studies, conducted by us in collaboration with Pfizer and independently by GlaskoSmithKlein, indicate that the pharmaceutical industry is considering this therapeutic approach for RRMS (137, 143). IL-7 signaling may actually have protective effects in RRMS. First, we find that patients with high IL-7 respond to IFN-β treatment, and therefore blocking IL-7 during IFN-β treatment could counteract the therapeutic effects (137). In addition, the IL7R polymorphisms suggest that blocking IL-7 may even harm RRMS patients. The polymorphism that confers risk for RRMS encodes for a splice variant of IL-7R that generates a soluble version of this receptor (138). This soluble receptor can then act as a molecular decoy in the plasma and in tissue. This could mean that RRMS patients have a decrease signaling initiated by IL-7, or the other IL7R ligand TSLP, and contributes to the development of RRMS.

Concluding remarks

The disease categorized as MS is a highly heterogeneous population, and it is gaining acceptance that RRMS is a collection of different syndromes that are under the same disease umbrella. The clinical unpredictability of this disease is exemplified by the variation in response to therapy, which makes it especially difficult for clinicians to choose the appropriate drug for their patients’ specific conditions. It is a great challenge for researchers to discover unique ways to identify responsiveness to therapy early after treatment begins or better yet before treatment is initiated.

In this review, we discussed data from preclinical experimental models, biomarker studies, and clinical trials from MS and other autoimmune diseases. As a whole, these observations demonstrate that MS is unique compared to other autoimmune disorders. In many autoimmune diseases, with the notable exception of MS, type I IFN is known to be pro-inflammatory and contributes to tissue destruction (3, 8, 85). In these autoimmune diseases, where type I IFN drives disease, blockade of TNF, BAFF, and IL-23 are therapeutic (56, 149). In the MS community, type I IFN is considered anti-inflammatory and is used to treat RRMS patients (5, 44). Remarkably, blockade of TNF, BAFF, and IL-23 failed to improve RRMS in clinical trials (92, 126, 150). In fact, the blockade of BAFF and TNF, two cytokines that belong in the TNF molecular family, worsen MS symptoms (126, 150).

Understanding the molecular similarity and differences in these diverse autoimmune diseases provides insight into the molecular pathologies of RRMS. Furthermore, it may provide some rationale on how clinicians can stratify RRMS patients and begin predicting treatment response.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a US National Institutes of Health grant 1K99NS075099-01 to R.C.A.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Isaacs A, Lindenmann J. Virus interference. I. The interferon. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1957;147:258–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pestka S, Krause CD, Walter MR. Interferons, interferon-like cytokines, and their receptors. Immunol Rev. 2004;202:8–32. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00204.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Foster GR. Pegylated interferons for the treatment of chronic hepatitis C: pharmacological and clinical differences between peginterferon-alpha-2a and peginterferon-alpha-2b. Drugs. 2010;70:147–165. doi: 10.2165/11531990-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kirkwood JM, et al. Mechanisms and management of toxicities associated with high-dose interferon alfa-2b therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:3703–3718. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.03.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arnason BG. Immunologic therapy of multiple sclerosis. Annu Rev Med. 1999;50:291–302. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.50.1.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nestle FO, et al. Plasmacytoid predendritic cells initiate psoriasis through interferon-alpha production. J Exp Med. 2005;202:135–143. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yao Y, et al. Type I interferon: potential therapeutic target for psoriasis? PLoS One. 2008;3:e2737. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palace J, Leite MI, Nairne A, Vincent A. Interferon Beta treatment in neuromyelitis optica: increase in relapses and aquaporin 4 antibody titers. Arch Neurol. 2010;67:1016–1017. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uzawa A, Mori M, Hayakawa S, Masuda S, Kuwabara S. Different responses to interferon beta-1b treatment in patients with neuromyelitis optica and multiple sclerosis. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17:672–676. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2009.02897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bennett L, et al. Interferon and granulopoiesis signatures in systemic lupus erythematosus blood. J Exp Med. 2003;197:711–723. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Comi G, et al. Comparison of two dosing frequencies of subcutaneous interferon beta-1a in patients with a first clinical demyelinating event suggestive of multiple sclerosis (REFLEX): a phase 3 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11:33–41. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(11)70262-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chan S, Kingwell E, Oger J, Yoshida E, Tremlett H. High-dose frequency beta-interferons increase the risk of liver test abnormalities in multiple sclerosis: a longitudinal study. Mult Scler. 2011;17:361–367. doi: 10.1177/1352458510388823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Axtell RC, et al. T helper type 1 and 17 cells determine efficacy of interferon-beta in multiple sclerosis and experimental encephalomyelitis. Nat Med. 2010;16:406–412. doi: 10.1038/nm.2110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Comabella M, et al. A type I interferon signature in monocytes is associated with poor response to interferon-beta in multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2009;132:3353–3365. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malucchi S, et al. One-year evaluation of factors affecting the biological activity of interferon beta in multiple sclerosis patients. J Neurol. 2010 doi: 10.1007/s00415-010-5844-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rio J, et al. Defining the response to interferon-beta in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis patients. Ann Neurol. 2006;59:344–352. doi: 10.1002/ana.20740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hillert J, Olerup O. HLA and MS. Neurology. 1993;43:2426–2427. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2426-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mingioli ES, McFarlin DE. Leukocyte surface antigens in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol. 1984;6:131–139. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(84)90034-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuchroo VK, Anderson AC, Waldner H, Munder M, Bettelli E, Nicholson LB. T cell response in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE): role of self and cross-reactive antigens in shaping, tuning, and regulating the autopathogenic T cell repertoire. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:101–123. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.081701.141316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abreu SL. Suppression of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis by interferon. Immunol Commun. 1982;11:1–7. doi: 10.3109/08820138209050718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Galligan CL, et al. Interferon-beta is a key regulator of proinflammatory events in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Mult Scler. 2010;16:1458–1473. doi: 10.1177/1352458510381259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prinz M, Kalinke U. New lessons about old molecules: how type I interferons shape Th1/Th17-mediated autoimmunity in the CNS. Trends Mol Med. 2010;16:379–386. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2010.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guo B, Chang EY, Cheng G. The type I IFN induction pathway constrains Th17-mediated autoimmune inflammation in mice. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1680–1690. doi: 10.1172/JCI33342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martin-Saavedra FM, Gonzalez-Garcia C, Bravo B, Ballester S. Beta interferon restricts the inflammatory potential of CD4+ cells through the boost of the Th2 phenotype, the inhibition of Th17 response and the prevalence of naturally occurring T regulatory cells. Mol Immunol. 2008;45:4008–4019. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Annunziato F, Romagnani S. Heterogeneity of human effector CD4+ T cells. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11:257. doi: 10.1186/ar2843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jager A, Kuchroo VK. Effector and regulatory T-cell subsets in autoimmunity and tissue inflammation. Scand J Immunol. 2010;72:173–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2010.02432.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.King C, Sprent J. Emerging cellular networks for regulation of T follicular helper cells. Trends Immunol. 2012;33:59–65. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Harrington LE, Mangan PR, Weaver CT. Expanding the effector CD4 T-cell repertoire: the Th17 lineage. Curr Opin Immunol. 2006;18:349–356. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Olsson T. Cytokines in neuroinflammatory disease: role of myelin autoreactive T cell production of interferon-gamma. J Neuroimmunol. 1992;40:211–218. doi: 10.1016/0165-5728(92)90135-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bettelli E, Sullivan B, Szabo SJ, Sobel RA, Glimcher LH, Kuchroo VK. Loss of T-bet, but not STAT1, prevents the development of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Exp Med. 2004;200:79–87. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stromnes IM, Cerretti LM, Liggitt D, Harris RA, Goverman JM. Differential regulation of central nervous system autoimmunity by T(H)1 and T(H)17 cells. Nat Med. 2008;14:337–342. doi: 10.1038/nm1715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Panitch HS, Hirsch RL, Haley AS, Johnson KP. Exacerbations of multiple sclerosis in patients treated with gamma interferon. Lancet. 1987;1:893–895. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)92863-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ferber IA, et al. Mice with a disrupted IFN-gamma gene are susceptible to the induction of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) J Immunol. 1996;156:5–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Harrington LE, et al. Interleukin 17-producing CD4+ effector T cells develop via a lineage distinct from the T helper type 1 and 2 lineages. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1123–1132. doi: 10.1038/ni1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Langrish CL, et al. IL-23 drives a pathogenic T cell population that induces autoimmune inflammation. J Exp Med. 2005;201:233–240. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haak S, et al. IL-17A and IL-17F do not contribute vitally to autoimmune neuro-inflammation in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:61–69. doi: 10.1172/JCI35997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ke Y, et al. Anti-inflammatory role of IL-17 in experimental autoimmune uveitis. J Immunol. 2009;182:3183–3190. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Durelli L, et al. T-helper 17 cells expand in multiple sclerosis and are inhibited by interferon-beta. Ann Neurol. 2009;65:499–509. doi: 10.1002/ana.21652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lock C, et al. Gene-microarray analysis of multiple sclerosis lesions yields new targets validated in autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Nat Med. 2002;8:500–508. doi: 10.1038/nm0502-500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kroenke MA, Carlson TJ, Andjelkovic AV, Segal BM. IL-12- and IL-23-modulated T cells induce distinct types of EAE based on histology, CNS chemokine profile, and response to cytokine inhibition. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1535–1541. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nagai T, Devergne O, van Seventer GA, van Seventer JM. Interferon-beta mediates opposing effects on interferon-gamma-dependent Interleukin-12 p70 secretion by human monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Scand J Immunol. 2007;65:107–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2006.01880.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McRae BL, Semnani RT, Hayes MP, van Seventer GA. Type I IFNs inhibit human dendritic cell IL-12 production and Th1 cell development. J Immunol. 1998;160:4298–4304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ramgolam VS, Sha Y, Jin J, Zhang X, Markovic-Plese S. IFN-beta inhibits human Th17 cell differentiation. J Immunol. 2009;183:5418–5427. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Benveniste EN, Qin H. Type I interferons as anti-inflammatory mediators. Sci STKE. 2007;2007:pe70. doi: 10.1126/stke.4162007pe70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hesse D, Sorensen PS. Using measurements of neutralizing antibodies: the challenge of IFN-beta therapy. Eur J Neurol. 2007;14:850–859. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2007.01769.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grossberg SE, Oger J, Grossberg LD, Gehchan A, Klein JP. Frequency and Magnitude of Interferon beta Neutralizing Antibodies in the Evaluation of Interferon beta Immunogenicity in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2010 doi: 10.1089/jir.2010.0038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hegen H, et al. Persistency of neutralizing antibodies depends on titer and interferon-beta preparation. Mult Scler. 2011 doi: 10.1177/1352458511426738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lanzillo R, et al. Predictive factors of neutralizing antibodies development in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis patients on interferon Beta-1b therapy. Neurol Sci. 2011;32:287–292. doi: 10.1007/s10072-011-0483-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hartung HP, et al. Interferon beta-1b-neutralizing antibodies 5 years after clinically isolated syndrome. Neurology. 2011;77:835–843. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31822c90d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Massart C, et al. Determination of interferon beta neutralizing antibodies in multiple sclerosis: improvement of clinical sensitivity of a cytopathic effect assay. Clin Chim Acta. 2008;391:98–101. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2008.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Serrano-Fernandez P, et al. Time course transcriptomics of IFNB1b drug therapy in multiple sclerosis. Autoimmunity. 2010;43:172–178. doi: 10.3109/08916930903219040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rani MR, et al. Heterogeneous, longitudinally stable molecular signatures in response to interferon-beta. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009;1182:58–68. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05068.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rudick RA, et al. Excessive biologic response to IFNbeta is associated with poor treatment response in patients with multiple sclerosis. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19262. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tzartos JS, et al. Interleukin-17 production in central nervous system-infiltrating T cells and glial cells is associated with active disease in multiple sclerosis. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:146–155. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Werner JL, et al. Neutrophils produce interleukin 17A (IL-17A) in a dectin-1- and IL-23-dependent manner during invasive fungal infection. Infect Immun. 2011;79:3966–3977. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05493-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Navarra SV, et al. Efficacy and safety of belimumab in patients with active systemic lupus erythematosus: a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2011;377:721–731. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61354-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Preble OT, Black RJ, Friedman RM, Klippel JH, Vilcek J. Systemic lupus erythematosus: presence in human serum of an unusual acid-labile leukocyte interferon. Science. 1982;216:429–431. doi: 10.1126/science.6176024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cunninghame Graham DS, et al. Association of NCF2, IKZF1, IRF8, IFIH1, and TYK2 with systemic lupus erythematosus. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002341. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fu Q, et al. Association of a functional IRF7 variant with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:749–754. doi: 10.1002/art.30193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ramos PS, et al. Genetic analyses of interferon pathway-related genes reveal multiple new loci associated with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:2049–2057. doi: 10.1002/art.30356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sandling JK, et al. A candidate gene study of the type I interferon pathway implicates IKBKE and IL8 as risk loci for SLE. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011;19:479–484. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2010.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kono DH, Baccala R, Theofilopoulos AN. Inhibition of lupus by genetic alteration of the interferon-alpha/beta receptor. Autoimmunity. 2003;36:503–510. doi: 10.1080/08916930310001624665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nacionales DC, et al. Deficiency of the type I interferon receptor protects mice from experimental lupus. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:3770–3783. doi: 10.1002/art.23023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liu Z, et al. Interferon-alpha accelerates murine systemic lupus erythematosus in a T cell-dependent manner. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63:219–229. doi: 10.1002/art.30087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ramanujam M, et al. Interferon-alpha treatment of female (NZW x BXSB)F(1) mice mimics some but not all features associated with the Yaa mutation. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:1096–1101. doi: 10.1002/art.24414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Merrill JT, et al. Safety profile and clinical activity of sifalimumab, a fully human anti-interferon alpha monoclonal antibody, in systemic lupus erythematosus: a phase I, multicentre, double-blind randomised study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70:1905–1913. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.144485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yao Y, et al. Neutralization of interferon-alpha/beta-inducible genes and downstream effect in a phase I trial of an anti-interferon-alpha monoclonal antibody in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:1785–1796. doi: 10.1002/art.24557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shah K, et al. Dysregulated balance of Th17 and Th1 cells in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Res Ther. 2010;12:R53. doi: 10.1186/ar2964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Veldhoen M, Hocking RJ, Atkins CJ, Locksley RM, Stockinger B. TGFbeta in the context of an inflammatory cytokine milieu supports de novo differentiation of IL-17-producing T cells. Immunity. 2006;24:179–189. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.van den Berg A, et al. Interleukin-17 induces hyperresponsive interleukin-8 and interleukin-6 production to tumor necrosis factor-alpha in structural lung cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2005;33:97–104. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2005-0022OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hwang SY, et al. IL-17 induces production of IL-6 and IL-8 in rheumatoid arthritis synovial fibroblasts via NF-kappaB- and PI3-kinase/Akt-dependent pathways. Arthritis Res Ther. 2004;6:R120–128. doi: 10.1186/ar1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Illei GG, et al. Tocilizumab in systemic lupus erythematosus: data on safety, preliminary efficacy, and impact on circulating plasma cells from an open-label phase I dosage-escalation study. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:542–552. doi: 10.1002/art.27221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.De Souza A, Ali-Shaw T, Strober BE, Franks AG., Jr Successful treatment of subacute lupus erythematosus with ustekinumab. Arch Dermatol. 2011;147:896–898. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2011.185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Pittock SJ, et al. Neuromyelitis optica and non organ-specific autoimmunity. Arch Neurol. 2008;65:78–83. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2007.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nakashima I, et al. Clinical and MRI features of Japanese patients with multiple sclerosis positive for NMO-IgG. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2006;77:1073–1075. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.080390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pittock SJ, Weinshenker BG, Lucchinetti CF, Wingerchuk DM, Corboy JR, Lennon VA. Neuromyelitis optica brain lesions localized at sites of high aquaporin 4 expression. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:964–968. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.7.964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Barkhof F, et al. Comparison of MRI criteria at first presentation to predict conversion to clinically definite multiple sclerosis. Brain. 1997;120 (Pt 11):2059–2069. doi: 10.1093/brain/120.11.2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ishizu T, et al. Intrathecal activation of the IL-17/IL-8 axis in opticospinal multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2005;128:988–1002. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Icoz S, et al. Enhanced IL-6 production in aquaporin-4 antibody positive neuromyelitis optica patients. Int J Neurosci. 120:71–75. doi: 10.3109/00207450903428970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Wang HH, et al. Interleukin-17-secreting T cells in neuromyelitis optica and multiple sclerosis during relapse. J Clin Neurosci. 18:1313–1317. doi: 10.1016/j.jocn.2011.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ye P, et al. Requirement of interleukin 17 receptor signaling for lung CXC chemokine and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor expression, neutrophil recruitment, and host defense. J Exp Med. 2001;194:519–527. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.4.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zhang Z, et al. Interleukin-17 causes neutrophil mediated inflammation in ovalbumin-induced uveitis in DO11.10 mice. Cytokine. 2009;46:79–91. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2008.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Shimizu J, et al. IFNbeta-1b may severely exacerbate Japanese optic-spinal MS in neuromyelitis optica spectrum. Neurology. 2010;75:1423–1427. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181f8832e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Warabi Y, Matsumoto Y, Hayashi H. Interferon beta-1b exacerbates multiple sclerosis with severe optic nerve and spinal cord demyelination. J Neurol Sci. 2007;252:57–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2006.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Feng X, et al. Type I interferon signature is high in lupus and neuromyelitis optica but low in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2012;313:48–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2011.09.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mehta LR, et al. Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus and anti-phospholipid antibody syndrome. Mult Scler. 2008;14:425–427. doi: 10.1177/1352458507084107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Racz E, et al. Effective treatment of psoriasis with narrow-band UVB phototherapy is linked to suppression of the IFN and Th17 pathways. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:1547–1558. doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cargill M, et al. A large-scale genetic association study confirms IL12B and leads to the identification of IL23R as psoriasis-risk genes. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:273–290. doi: 10.1086/511051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Nair RP, et al. Polymorphisms of the IL12B and IL23R genes are associated with psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:1653–1661. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5701255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chan JR, et al. IL-23 stimulates epidermal hyperplasia via TNF and IL-20R2-dependent mechanisms with implications for psoriasis pathogenesis. J Exp Med. 2006;203:2577–2587. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Krueger GG, et al. A human interleukin-12/23 monoclonal antibody for the treatment of psoriasis. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:580–592. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa062382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Segal BM, Constantinescu CS, Raychaudhuri A, Kim L, Fidelus-Gort R, Kasper LH. Repeated subcutaneous injections of IL12/23 p40 neutralising antibody, ustekinumab, in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a phase II, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised, dose-ranging study. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:796–804. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70173-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Coimbra S, et al. Interleukin (IL)-22, IL-17, IL-23, IL-8, vascular endothelial growth factor and tumour necrosis factor-alpha levels in patients with psoriasis before, during and after psoralen-ultraviolet A and narrowband ultraviolet B therapy. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163:1282–1290. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2010.09992.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Fujishima S, et al. Involvement of IL-17F via the induction of IL-6 in psoriasis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2010;302:499–505. doi: 10.1007/s00403-010-1033-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Hueber W, et al. Effects of AIN457, a fully human antibody to interleukin-17A, on psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, and uveitis. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:52ra72. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.van der Fits L, van der Wel LI, Laman JD, Prens EP, Verschuren MC. In psoriasis lesional skin the type I interferon signaling pathway is activated, whereas interferon-alpha sensitivity is unaltered. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;122:51–60. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202X.2003.22113.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Reizis B, Bunin A, Ghosh HS, Lewis KL, Sisirak V. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells: recent progress and open questions. Annu Rev Immunol. 2011;29:163–183. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-031210-101345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hida S, et al. CD8(+) T cell-mediated skin disease in mice lacking IRF-2, the transcriptional attenuator of interferon-alpha/beta signaling. Immunity. 2000;13:643–655. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00064-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Scavo S, et al. Verrucous psoriasis in a patient with chronic C hepatitis treated with interferon. Clin Drug Investig. 2004;24:427–429. doi: 10.2165/00044011-200424070-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.La Mantia L, Capsoni F. Psoriasis during interferon beta treatment for multiple sclerosis. Neurol Sci. 2010;31:337–339. doi: 10.1007/s10072-009-0184-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Lopez-Lerma I, Iranzo P, Herrero C. New-onset psoriasis in a patient treated with interferon beta-1a. Br J Dermatol. 2009;160:716–717. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2008.09005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Webster GF, Knobler RL, Lublin FD, Kramer EM, Hochman LR. Cutaneous ulcerations and pustular psoriasis flare caused by recombinant interferon beta injections in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;34:365–367. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(07)80010-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Seckin D, Durusoy C, Sahin S. Concomitant vitiligo and psoriasis in a patient treated with interferon alfa-2a for chronic hepatitis B infection. Pediatr Dermatol. 2004;21:577–579. doi: 10.1111/j.0736-8046.2004.21512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Downs AM, Dunnill MG. Exacerbation of psoriasis by interferon-alpha therapy for hepatitis C. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2000;25:351–352. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2000.00655-4.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Musch E, Andus T, Malek M. Induction and maintenance of clinical remission by interferon-beta in patients with steroid-refractory active ulcerative colitis-an open long-term pilot trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:1233–1239. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Pena-Rossi C, et al. Clinical trial: a multicentre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-finding, phase II study of subcutaneous interferon-beta-1a in moderately active ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Mannon PJ, et al. Suppression of inflammation in ulcerative colitis by interferon-{beta}-1a is accompanied by inhibition of IL-13 production. Gut. 2010;60:449–455. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.226860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Martinelli S, et al. Induction of genes mediating interferon-dependent extracellular trap formation during neutrophil differentiation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:44123–44132. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405883200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Borregaard N. Neutrophils, from marrow to microbes. Immunity. 2010;33:657–670. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Krumbholz M, et al. Interferon-beta increases BAFF levels in multiple sclerosis: implications for B cell autoimmunity. Brain. 2008;131:1455–1463. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kato A, Truong-Tran AQ, Scott AL, Matsumoto K, Schleimer RP. Airway epithelial cells produce B cell-activating factor of TNF family by an IFN-beta-dependent mechanism. J Immunol. 2006;177:7164–7172. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.7164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ittah M, et al. B cell-activating factor of the tumor necrosis factor family (BAFF) is expressed under stimulation by interferon in salivary gland epithelial cells in primary Sjogren’s syndrome. Arthritis Res Ther. 2006;8:R51. doi: 10.1186/ar1912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Vaknin-Dembinsky A, Brill L, Orpaz N, Abramsky O, Karussis D. Preferential increase of B-cell activating factor in the cerebrospinal fluid of neuromyelitis optica in a white population. Mult Scler. 2010;16:1453–1457. doi: 10.1177/1352458510380416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Becker-Merok A, Nikolaisen C, Nossent HC. B-lymphocyte activating factor in systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis in relation to autoantibody levels, disease measures and time. Lupus. 2006;15:570–576. doi: 10.1177/0961203306071871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Liu Z, Davidson A. BAFF and selection of autoreactive B cells. Trends Immunol. 32:388–394. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Hsu HC, et al. Interleukin 17-producing T helper cells and interleukin 17 orchestrate autoreactive germinal center development in autoimmune BXD2 mice. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:166–175. doi: 10.1038/ni1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Xie S, et al. IL-17 activates the canonical NF-kappaB signaling pathway in autoimmune B cells of BXD2 mice to upregulate the expression of regulators of G-protein signaling 16. J Immunol. 2010;184:2289–2296. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Tohyama M, et al. IL-17 and IL-22 mediate IL-20 subfamily cytokine production in cultured keratinocytes via increased IL-22 receptor expression. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:2779–2788. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Tohyama M, Yang L, Hanakawa Y, Dai X, Shirakata Y, Sayama K. IFN-alpha Enhances IL-22 Receptor Expression in Keratinocytes: A Possible Role in the Development of Psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2012 doi: 10.1038/jid.2011.468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Kebir H, et al. Human Th17 lymphocytes promote blood-brain barrier disruption and central nervous system inflammation. Nat Med. 2007;13:1173–1175. doi: 10.1038/nm1651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Eyerich S, et al. IL-22 and TNF-alpha represent a key cytokine combination for epidermal integrity during infection with Candida albicans. Eur J Immunol. 2011;41:1894–1901. doi: 10.1002/eji.201041197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Wolk K, Kunz S, Witte E, Friedrich M, Asadullah K, Sabat R. IL-22 increases the innate immunity of tissues. Immunity. 2004;21:241–254. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Pender MP. Does Epstein-Barr virus infection in the brain drive the development of multiple sclerosis? Brain. 2009;132:3196–3198. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Mehling M, Kappos L, Derfuss T. Fingolimod for multiple sclerosis: mechanism of action, clinical outcomes, and future directions. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2011;11:492–497. doi: 10.1007/s11910-011-0216-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Shiow LR, et al. CD69 acts downstream of interferon-alpha/beta to inhibit S1P1 and lymphocyte egress from lymphoid organs. Nature. 2006;440:540–544. doi: 10.1038/nature04606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Hartung HP, Kieseier BC. Atacicept: targeting B cells in multiple sclerosis. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2010;3:205–216. doi: 10.1177/1756285610371146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Kim SS, Richman DP, Zamvil SS, Agius MA. Accelerated central nervous system autoimmunity in BAFF-receptor-deficient mice. J Neurol Sci. 2011;306:9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Yang M, et al. Novel function of B cell-activating factor in the induction of IL-10- producing regulatory B cells. J Immunol. 2010;184:3321–3325. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Zhang X, Deriaud E, Jiao X, Braun D, Leclerc C, Lo-Man R. Type I interferons protect neonates from acute inflammation through interleukin 10-producing B cells. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1107–1118. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Platanias LC. Mechanisms of type-I- and type-II-interferon-mediated signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:375–386. doi: 10.1038/nri1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Berenson LS, Gavrieli M, Farrar JD, Murphy TL, Murphy KM. Distinct characteristics of murine STAT4 activation in response to IL-12 and IFN-alpha. J Immunol. 2006;177:5195–5203. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.8.5195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Tanabe Y, Nishibori T, Su L, Arduini RM, Baker DP, David M. Cutting edge: role of STAT1, STAT3, and STAT5 in IFN-alpha beta responses in T lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2005;174:609–613. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.2.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Catalfamo M, et al. CD4 and CD8 T cell immune activation during chronic HIV infection: roles of homeostasis, HIV, type I IFN, and IL-7. J Immunol. 2011;186:2106–2116. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Nguyen KB, Cousens LP, Doughty LA, Pien GC, Durbin JE, Biron CA. Interferon alpha/beta-mediated inhibition and promotion of interferon gamma: STAT1 resolves a paradox. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:70–76. doi: 10.1038/76940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Wong LH, Hatzinisiriou I, Devenish RJ, Ralph SJ. IFN-gamma priming up- regulates IFN-stimulated gene factor 3 (ISGF3) components, augmenting responsiveness of IFN-resistant melanoma cells to type I IFNs. J Immunol. 1998;160:5475–5484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Chitnis T, et al. Effect of targeted disruption of STAT4 and STAT6 on the induction of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:739–747. doi: 10.1172/JCI12563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Lee LF, et al. IL-7 promotes T(H)1 development and serum IL-7 predicts clinical response to interferon-beta in multiple sclerosis. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:93ra68. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Gregory SG, et al. Interleukin 7 receptor alpha chain (IL7R) shows allelic and functional association with multiple sclerosis. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1083–1091. doi: 10.1038/ng2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Lundmark F, et al. Variation in interleukin 7 receptor alpha chain (IL7R) influences risk of multiple sclerosis. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1108–1113. doi: 10.1038/ng2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.von Freeden-Jeffry U, Vieira P, Lucian LA, McNeil T, Burdach SE, Murray R. Lymphopenia in interleukin (IL)-7 gene-deleted mice identifies IL-7 as a nonredundant cytokine. J Exp Med. 1995;181:1519–1526. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.4.1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Seddon B, Tomlinson P, Zamoyska R. Interleukin 7 and T cell receptor signals regulate homeostasis of CD4 memory cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:680–686. doi: 10.1038/ni946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Puel A, Ziegler SF, Buckley RH, Leonard WJ. Defective IL7R expression in T(-)B(+)NK(+) severe combined immunodeficiency. Nat Genet. 1998;20:394–397. doi: 10.1038/3877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Liu X, et al. Crucial role of interleukin-7 in T helper type 17 survival and expansion in autoimmune disease. Nat Med. 2010;16:191–197. doi: 10.1038/nm.2077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Davis CC, Marti LC, Sempowski GD, Jeyaraj DA, Szabolcs P. Interleukin-7 permits Th1/Tc1 maturation and promotes ex vivo expansion of cord blood T cells: a critical step toward adoptive immunotherapy after cord blood transplantation. Cancer Res. 2010;70:5249–5258. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Ariizumi K, Meng Y, Bergstresser PR, Takashima A. IFN-gamma-dependent IL-7 gene regulation in keratinocytes. J Immunol. 1995;154:6031–6039. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Oshima S, et al. Interferon regulatory factor 1 (IRF-1) and IRF-2 distinctively up-regulate gene expression and production of interleukin-7 in human intestinal epithelial cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:6298–6310. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.14.6298-6310.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Nanjappa SG, Kim EH, Suresh M. Immunotherapeutic effects of IL-7 during a chronic viral infection in mice. Blood. 2011;117:5123–5132. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-323154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Gregersen PK, Olsson LM. Recent advances in the genetics of autoimmune disease. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:363–391. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Herrier RN. Advances in the treatment of moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2011;68:795–806. doi: 10.2146/ajhp100227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Bellesi M, Logullo F, Di Bella P, Provinciali L. CNS demyelination during anti- tumor necrosis factor alpha therapy. J Neurol. 2006;253:668–669. doi: 10.1007/s00415-005-0055-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]