Abstract

Introduction

This study explored the relationship between depression, stigma, and risk behaviors in a multisite study of high risk youth living with HIV (YLH) in the United States.

Methods

All youth met screening criteria for either problem level substance use, current sexual risk and/or suboptimal HIV medication adherence. Problem level substance use behavior was assessed with the CRAFFT, a 6-item adolescent screener. A single item was used to screen for current sexual risk and for a HIV medication adherence problem. Stigma and depression were measured via standard self-report measures.

Results

Multiple regression analysis revealed that behavioral infection, older age, more problem behaviors, and greater stigma each contributed to the prediction of higher depression scores in YLH. Associations between depression, stigma, and problem behaviors are discussed. More than half of the youth in this study scored at or above the clinical cut-off for depression. Results highlight the need for depression focused risk reduction interventions that address stigma in YLH.

Discussion

Study outcomes suggest that interventions are needed to address stigma and depression not only among youth living with HIV but in the communities in which they live.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, Stigma, Depression

REVIEW OF LITERATURE

In the United States approximately 20.9 million Americans eighteen or older have a mood disorder and about 20% of teens will experience depression before they reach adulthood (Kessler, Chui, Demler, & Walters, 2005). Fernando (2009) reports that depression in HIV + persons are common with rates as high as 30–40%. High rates of depression in youth living with HIV (YLH) have also been reported and have shown to be associated with health risk behaviors and depression (Murphy, Duranko, Moscicki, Vermund, et al 2001). The Center for Disease Control (CDC) reported in April 2009 that more than one million people are living with HIV in the United States and that every 9 ½ minutes someone is infected with HIV in the U.S.(www.cdc.gov).

High rates of depression in people living with HIV may be, in part, due to stigma. HIV/AIDS – related stigma can be described as a process of devaluation of people either living with or associated with HIV and AIDS (USAID, 2000). The primary route of HIV infection is sex. Stigma often stems from the underlying stigmatization of sex. Stigma has been describe as a complex, social phenomenon involving interplay between social and economic factors in the environment and psychosocial issues of affected individuals (Parker and Aggleton, 2003).

A few single site studies have examined the relationship between stigma and depression in youth. Dowshen, Binns, & Garofalo (2009) found high levels of stigma positively correlated with low self-esteem and higher depression among a diverse group of 310 HIV infected young men who sex with men (YMSM). Understanding this relationship is important since young men who have sex with men (YMSM) represent an increasing number of new HIV infections in many urban communities in the United States (CDC, 2009, www.cdc.org). HIV also affects young women. (Rongkavilit, Wright, Chen, Naar-King, et al, 2010; Wright, Naar-King, Lam, Templin, et al, 2007). Based on data from 34 states with long-term confidential name-based HIV reporting, CDC reported that 25% of HIV/AIDS diagnoses among adolescents and adults were females (CDC HIV/AIDS Facts, 2009). A recent study of seventy (70) Thai youth living with HIV (TYLH) of whom 58% were female found that 53% of the study population scored at the clinically significant mental health problem range (Rongkalvilit, et al, 2010). Another study suggests that managing stigma in the lives of HIV + youth living in Australia, Canada, UK, and USA entails managing silence in the communities in which they live (Fielden, Chapman, & Cadell, 2010).

In an exploratory study using baseline data from a multi-site risk reduction intervention study of the Adolescent Trials Network (ATN), we assessed the relationship between depression, stigma, and risk behaviors in a diverse sample of youth living with HIV. We hypothesized that increased depression would be associated with increased stigma and number of problem level risk behaviors.

METHODS

Procedures

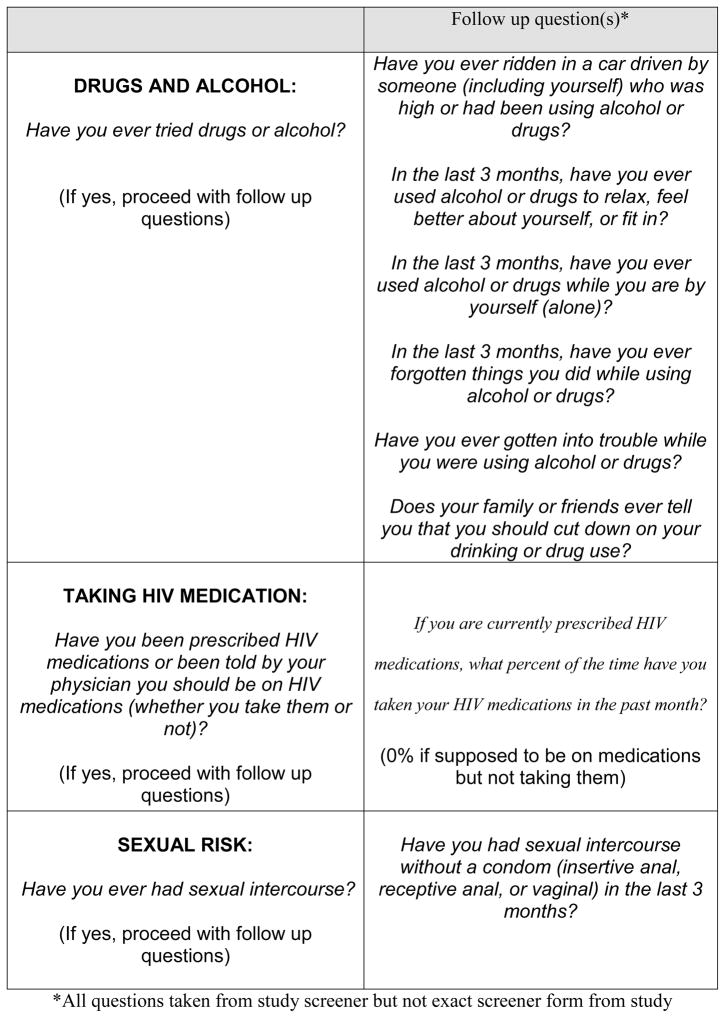

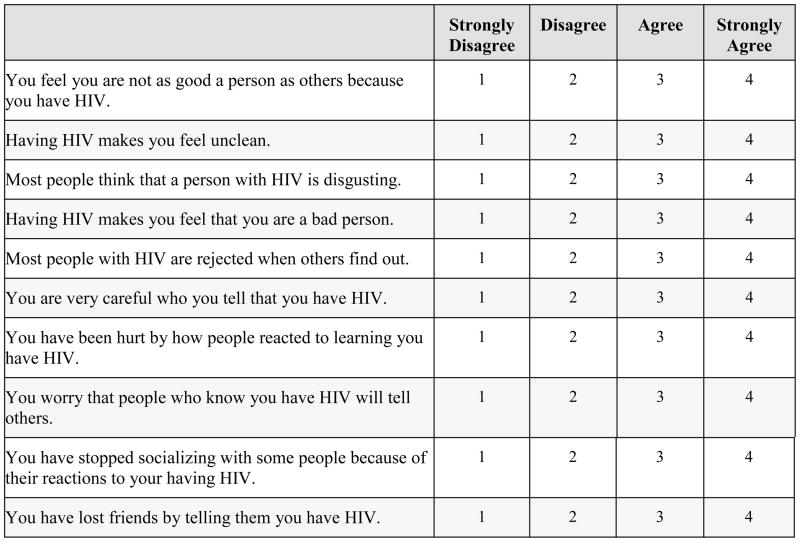

The protocol was approved by each site’s Institutional Review Board and a certificate of confidentiality was obtained from the National Institutes of Health. Youth were recruited from four Adolescent Trials Network (ATN) sites located in Fort Lauderdale, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Los Angeles, and one non-ATN site located in Detroit. All five adolescent medicine clinics offered multidisciplinary care including social work, case management, and access to mental health services. Youth were approached at the time of a regularly scheduled visit or at supportive activities. Upon determination of eligibility, written informed consent was obtained. A waiver of parental consent was permitted for youth under age 18 as per site IRB approval under 45 CFR Part 46.408 © that allows youth access to HIV treatment, care and research without parental permission. By use of a brief screener (Figure 1), risk behaviors were identified in youth living with HIV. The 10 item Stigma questionnaire (Figure 2) measures were collected along with 19 other measures using computer assisted personal interviewing (CAPI) where the researcher conducts a face-to-face interview but enters responses directly into the computer. Preliminary outcomes at 3 months of correlations between stigma scale, depression and psychosocial variables are presented.

FIGURE 1.

Study Screener

FIGURE 2.

Stigma Questionnaire

I am going to read a list of statements that you may or may not agree with. For each statement, please tell me whether you Strongly Agree, Agree, Disagree, or Strongly Disagree.

Study methods have been previously reported (Wright et al, 2007; Tanney, Naar-King, Murphy, & Parsons, et al, 2010; Naar-King, Kolmodin, Parsons, Murphy, et al, 2010, Naar-King, Parsons, Murphy, Kolmodin, et al, 2010). In brief, YLH were participants in a randomized clinical trial examining the efficacy of a motivational intervention addressing multiple risk behaviors and baseline data were used in the current study. YLH were screened for problem level substance use behavior with the CRAFFT (Car, Relax, Alone, Forget, Friends, and Trouble) (Knight, Shrier, Bravender, Farrell, et al, 1999), a 6-item adolescent screener that combines items from 3 existing screening measures. A single item determined screening for current sexual risk behavior where YLH endorsed the presence or absence of an unprotected intercourse act in the previous three months. A single item determined screening for a medication adherence problem where YLH endorsed whether or not they were less than 90% adherent in the last month. If they were prescribed medications but had refused them, this was considered less than 90% adherent. The screener also included gender, age, and mode of HIV infection.

Youth with at least one problem level risk behavior (sexual risk, medication non-adherence, or substance use) were recruited from four Adolescent Trials Network (ATN) sites, and one non-ATN site (see Table 1). Of the 205 participants enrolled in the study, 24 youth did not complete all baseline measures. The current sample consisted of 186 participants. Youth completed the baseline assessment using a computer assisted personal interviewing (CAPI) method via an internet based application. Responses CAPI questions were entered into the computer by the research interviewer in a confidential manner. All participant responses were anonymous and no personal identifying information was recorded during the computer session.

TABLE 1.

Sample Demographics by Site: (N=186)

| Site | African American* | Sexual Minority*1 | Female* | Perinatally infected?* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Los Angeles | 48.8% | 48.8% | 37.2% | 9.3% |

| Philadelphia | 91.1 | 64.7 | 44.1 | 5.9 |

| Baltimore | 100.0 | 35.3 | 55.6 | 13.9 |

| Fort Lauderdale | 84.8 | 3.0 | 81.8 | 36.4 |

| Detroit | 97.5 | 60.5 | 25.0 | 20.0 |

Significant difference across sites, p ≤ .05

Sexual Minority – LGBT (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender)

Measures

Youth completed a demographic questionnaire as well as the following baseline measures:

Depression

The depression scale of the Brief Symptom Inventory measured symptom patterns of depression. The BSI has shown evidence of reliability and validity in many studies of medical, psychiatric, and non-patient populations (Derogatis & Spencer, 1982) as well as in youth living with HIV (Naar-King, Wright, Parsons, Frey, et al, 2006b, 2006c). The BSI yields t-scores where scores greater than 65 indicate clinical distress.

Stigma

Youth completed a shortened version of the Berger, Ferrans, & Lashley, (2001) stigma scale (Figure 2) which showed adequate reliability and validity in a single site study of YLH (Wright et al, 2007). Ten items rated on a 4 point scale (1=Strongly Disagree to 4=Strongly Agree) measure Personalized Stigma, Disclosure Concerns, Negative Self-image, and Public Attitudes. Reliability in the current sample as measured by Cronbach’s alpha was 0.8.

RESULTS

Of the 186 participants, 65.6 % (122) had problem level substance use, 44.1% (82) for HIV medication non-adherence, and 53.8% (100) for sexual risk. Among the 186 participants, 46.2% (86) had one of these problem behaviors, 44.1% (82) had two problem behaviors and 9.7% (18) had all three problem behaviors. More than half of youth (52%) scored at or above the clinical cut-off for depression. Mean stigma score was 2.35 (SD=.61). Table 2 shows bivariate correlations between depression, stigma, number of problem behaviors and demographic variables.

TABLE 2.

Bivariate Correlations among Variables

| Variable | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Depression | .44** | .27** | .10 | −.16* | −.29** | .32** | .22** |

| 2. Stigma Total | -- | .01 | .02 | .04 | .03 | .05 | .004 |

| 3. Problem Behaviors | -- | .10 | −.16* | −.07 | .22** | .22* | |

| 4. Race | -- | −.14 | −.05 | .07 | .11 | ||

| 5. Gender | -- | .18 | −.07 | −.71** | |||

| 6. Perinatally Infected | -- | −.40** | −.40** | ||||

| 7. Age | -- | .09 | |||||

| 8. Sexual Orientation | -- |

p < .05.

p<.01

Variables associated with depression at p<.10 were entered into a multiple regression model (age, sexual minority, perinatally versus behaviorally infected, number of problem behaviors, and stigma). Multiple regression analysis revealed that behavioral infection (standardized beta of −.15, t =−2.03, p < .05), older age (standardized beta of .21, t=3.00, p<.01), more problem behaviors (standardized beta of .19, t=2.91, p<.01), and higher stigma (standardized beta of .42, t= 6.76, p<.01) each contributed unique variance to the prediction of higher depression scores. Sexual minority status was not independently predictive of depression (p=.14). The model accounted for 35% of the variance in depression (F (5,181) = 18.64, p <01).

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated the relationship between depression and stigma in a multi-site sample of youth living with HIV (YLH) and that both stigma and risk behavior independently contributed to the variance in depression. Assessing youth with higher stigma for depression could help providers to intervene early with treatment options for the depression before depressive symptoms worsen. Reducing HIV related stigma and depression among minority youth could decrease some of the barriers to healthy behaviors, such as treatment adherence and safer sex behavior. In addition, such interventions might help to alleviate the negative consequences from the impact of stigma and depression in YLH.

A limitation to this study is that it is a sample of urban primarily African American youth and a more diverse sample may show different results. Another limitation is this sample of YLH agreed to a treatment study and these were youth who acknowledged they engaged in high risk behaviors. There is also a lack of clarity in the conceptualization and measurement of stigma at the individual level that can affect the youth’s response on the measure. In addition, the community context of YLH could affect their level of stigma and depression as well as their response to stigma and depression.

In conclusion, studies in resource-poor countries have begun to address the effect of community based interventions to reduce stigma. In a recent study conducted in China to reduce HIV-related stigma,Lin-Jin Lang and colleagues (2010) found that their intervention reduced the level of HIV-related stigmatizing attitudes toward people living with HIV/AIDS in a Chinese community. This intervention provided HIV transmission knowledge and skill training about how to communicate with others in the community about HIV prevention and safer sex behaviors. Over 3,550 Chinese market workers participated in this study. At 12 month and 24 month follow-up, the results demonstrated positive attitude changes associated with HIV-related stigma among these market workers. Studies to reduce HIV stigma in urban US communities are warranted. There is a need to provide focused risk reduction interventions at both the societal and individual levels. Finally, additional research and interventions are needed to address stigma and depression not only among YLH but the communities in which they live.

Acknowledgments

The Adolescent Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions (ATN) supported this work [U01-HD040533 and U01-HD040474] from the National Institutes of Health through the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (B. Kapogiannis, S. Lee)], with supplemental funding from the National Institutes on Drug Abuse (N. Borek) and Mental Health (P. Brouwers, S. Allison). The study was scientifically reviewed by the ATN’s Behavioral Leadership Group. Network, scientific and logistical support was provided by the ATN Coordinating Center (C. Wilson, C. Partlow) at The University of Alabama at Birmingham. Network operations and data management support was provided by the ATN Data and Operations Center at Westat, Inc. (J. Korelitz, J. Davidson, and B. Harris). We acknowledge the contribution of the investigators and staff at the following ATN 004 sites that participated in this study: Children’s Diagnostic and Treatment Center (Ana Puga, MD, Esmine Leonard, BSN, Zulma Eysallenne, RN); Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles (Marvin Belzer, MD, Cathy Salata, RN, Diane Tucker, RN, MSN); University of Maryland (Ligia Peralta, MD, Leonel Flores, MD, Esther Collinetti, BA); University of Pennsylvania and the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (Bret Rudy, MD, Mary Tanney, CPNP, MSN, MPH, Naini Seth, BSN, Kelly Lannutti, BA); University of Southern California (Andrea Kovacs, M.D.,), and Wayne State University Horizons Project (K. Wright, D.O., P. Lam, M.A., V. Conners, B.A.). We sincerely thank the youth who participated in this project.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None to report

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Mary R. Tanney, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Sylvie Naar-King, Wayne State University

Karen MacDonnel, Wayne State University

References

- Berger BE, Ferrans CE, Lashley FR. Measuring stigma in people with HIV: psychometric assessment of the HIV stigma scale. Research Nursing Health. 2001;24:518–529. doi: 10.1002/nur.10011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. 2009 www.cdc.gov.

- Derogatis L, Spencer P. Brief Symptom Inventory: Administration, Scoring, and Procedures Manual-I. Baltimore: Clinical Psychometric Research, NC; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Dowshen N, Binns HJ, Garofalo R. Experiences of HIV-related stigma among young men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2009;23 (5):371–376. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrando SJ. Psychopharmacologic treatment of patients with HIV/AIDS. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2009;11 (3):235–242. doi: 10.1007/s11920-009-0036-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fielden SJ, Chapman GE, Cadell S. Managing stigma in adolescent HIV: silence, secrets, and sanctioned spaces. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 2010 Nov;2:1–15. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2010.525665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of twelve-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62(6):617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knight JR, Shrier LA, Bravender TJ, Farrell M, Vander Bilt J, Shafer HJ. A new brief screen for adolescent substance abuse. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 1999;53:591–596. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.6.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin-Jin Lang LL, Lin C, Wu Z, Rotheram-Borus MJ. HIV prevention intervention to reduce HIV-related stigma: evidence from China. AIDS. 2010;24 (1):115–121. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283313e83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy DA, Durako S, Moscicki AB, Vermund SH, Yong MA, Schwarz DF. No change in health risk behaviors over time among HIV infected Adolescents in care: role of psychological distress. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2001 Sep;29 (3S):57–63. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(01)00287-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naar-King S, Wright K, Parsons JT, Frey M, Templin T, Ondersma S. Transtheoretical model and condom use in HIV-positive youths. Health Psychology. 2006b;25(5):648–652. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.5.648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naar-King S, Wright K, Parsons JT, Frey M, Templin T, Ondersma S. Transtheoretical model and substance use in HIV-positive youth. AIDS Care. 2006c;18(7):839–845. doi: 10.1080/09540120500467075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naar-King S, Kolmodin K, Parsons J, Murphy D the ATN 004 Protocol Team. Psychosocial factors and substance use in high risk youth living with HIV: A multisite study. AIDS Care. 2010;22(4):475–482. doi: 10.1080/09540120903220279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naar-King S, Parsons J, Murphy D, Kolmodin K, Harris R the ATN 004 Protocol Team. A multisite randomized trial of Healthy Choices: design and preliminary outcomes of Motivational Enhancement Therapy targeting multiple risk behaviors in youth living with HIV. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;46(5):422–428. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.11.198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker R, Aggleton P. HIV and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: a conceptual framework and implications for action. Social Science and Medicine. 2003;57 (1):15–24. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00304-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rongkavilit C, Wright K, Chen X, Naar-King S, Chuenyam T, Phanuphak P. HIV stigma, disclosure and psychosocial distress among Thai youth living with HIV. International Journal of STD and AIDS. 2010;21 (2):126–132. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2009.008488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanney M, Naar-King S, Murphy D, Parsons J, Janisse H. Multiple risk behaviors among youth living with human immunodeficiency virus in five U. S. cities. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;46 (1):11–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combating HIV/AIDS stigma, Discrimination and Denial: What way forward. June 23, 2000, unpublished paper. Washington, DC: USAID; Jun 23, 2000. USAID concept paper. www.usaid.org. [Google Scholar]

- Wright K, Naar-King S, Lam P, Templin T, Frey M. Stigma Scale Revised: Reliability and Validity of a brief measure of stigma for HIV + youth. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2007;40:96–98. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]