Abstract

Researchers studying infertility from the perspective of anthropology and other the social sciences seldom examine the assumptions embedded in the biomedical definition of infertility. Implicit in the biomedical definition is the assumption that people can be divided straightforwardly into those who are trying to conceive and those who are not trying to conceive. If being infertile implies “intent to conceive,” we must recognize that there are various degrees of intent and that the line between the fertile and the infertile is not as sharp as is usually imagined. Drawing on structured interview data collected from a random sample of Midwestern U.S. women and from qualitative interviews, we demonstrate that that there is a wide range of intent among those classified as infertile according to the biomedical definition. We explore the implications of this for research.

Keywords: infertility, pregnancy intentions, medicalization

Women’s lives are increasingly becoming medicalized (Inhorn 2006). Innovative work by feminist social scientists has helped to situate reproduction at the center of social theory (Rapp 2001) and to draw attention to the medicalization of reproduction (Davis-Floyd 1992; Lock 2001; Martin 1987; Rapp 2001; Rothman 1986). Medicalization is particularly evident in the shift from infertility as a private problem of couples to a medical condition that focuses primarily on women (Becker 2000; Bell 2009; Franklin 1997; Thompson 2005).1 The modern medicalization of infertility began in earnest with the development of fertility drugs in the United States in the 1950s (Greil 1991) but has proceeded even more rapidly since the development of such assisted reproductive technologies as in vitro fertilization and intracytoplasmic sperm injection.

When a condition is medicalized, biomedical agents assume the authority over defining and interpreting the condition, expanding their role in determining how it is to be treated, controlling access to treatment, and monitoring compliance with treatment regimens (Conrad and Schneider 1980). A major source of the increasing hegemony of the biomedical model is its appearance of neutrality and objectivity (Bell 2009). But definitions do not simply emerge out of unsocialized space. Rather, they are created by actors for a specific purpose. According to the Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (2008), the leading professional society for reproductive medicine in the United States, infertility is:

a disease defined by the failure to achieve a successful pregnancy after 12 months or more of regular unprotected intercourse. Earlier evaluation may be justified based on medical history and physical findings and is warranted after 6 months for women over age 35 years.2

It seems clear that a key purpose of the biomedical definition of infertility is to identify potential patients. The word “disease” at the beginning of this definition signals that infertility is most appropriately treated by medical practitioners. Because 85 percent of couples who achieve pregnancy without medical intervention will do so within a year, it is not unreasonable to suggest the 12-month cutoff to potential patients who think they may be in need of services (Rowe et al. 2000). At the same time, the definition makes it clear that no couple is actually excluded from the ranks of the infertile just because they fail to meet the length criterion. Whether or not couples are trying to or intending to conceive is not a formal part of this definition, and most medical and epidemiological definitions of infertility do not make intention an explicit criterion for inclusion in the category “infertile” (Schmidt and Münster 1995). Despite little explicit discussion of intentions, because most women and couples come to medical professionals for help getting pregnant, we suspect that intention to become pregnant is presumed in the “12 months of unprotected intercourse” criterion for infertility.

Biomedical definitions of health conditions appear on the surface to be free from the influence of values (Mishler et al. 1981), but, as Daston (1995) has argued, all scientific endeavors are built on a “moral economy.” The moral economy of biomedicine involves such issues as who is responsible for maintaining health, which individuals with what conditions require treatment, what is to be counted as evidence in support of a diagnosis, what constitutes a cure, and so on. Contemporary conceptions of “biological citizenship” emphasize the notion that the responsible individual practices a lifestyle calculated to maximize health and reduce the need for medical treatment (Herzlich and Pierret 1987; Rose and Novas 2005; Whyte 2009). Implicit in the contemporary understanding of biological citizenship is the belief that some people are more worthy of treatment than others. Specifically with regard to reproduction, Colen (1986) uses the phrase “stratified reproduction” to refer to the fact that reproduction is structured across social and cultural boundaries, enhancing reproductive control for some women and reducing it for other women.

In the case of infertility, for example, policymakers and scholars are often more concerned about overpopulation than infertility in non-Western countries (Inhorn and Birenbaum-Carmeli 2008; Nachtigall 2005, van Balen and Gerrits 2001). Evidence that women in non-Western countries have fewer entitlements as biological citizens than women in the West emerges in the emphasis on overpopulation, rather than infertility, despite the devastating consequences of infertility for many women in non-Western societies (Feldman-Savelsberg 1999; Handwerker 1995; Hollos 2003; Inhorn 1994, 1996; Inhorn and Bharadwaj 2008; Leonard 2002; Pashigian 2002). Within the United States, images of the typical infertility patient center on middle-class white women, leaving poor and nonwhite women constructed as hyper-fertile (Bell 2009; Sandelowski and de Lacy 2002). In the United States, where a market model of medicine prevails, infertility treatment is expensive, and most states do not mandate insurance coverage. Infertility patients therefore represent a subset of infertile women who have both a strong desire to become pregnant and the social and material resources that will allow them to do “whatever it takes” to have a child. Thus, the dominant image of “infertile woman” has become economically privileged women who attend infertility clinics.3

Medical anthropologists are less interested in identifying potential patients for infertility clinics and more concerned to understand the process by which individuals come to identify themselves as infertile, to describe the experience of infertility in various local contexts, to document and account for the steps the infertile take to resolve their situation, and to interpret the experience of infertility “treatment” in both medical and nonmedical contexts. There is, therefore, no reason why definitions and concepts used by medical professionals should be adopted in social science research. According to Lock (2001:483), “one contribution of medical anthropology is to monitor concepts and categories frequently used in the social, medical, epidemiological sciences, bioethics, and feminist theory.” There is an increasingly recognized need for social scientists to develop ethnographically informed measures to guide their research (Hirsch 1998). It is our goal here to present a more ethnographically informed approach to the concept of “infertility” than is currently employed in most contemporary social scientific research. Drawing on telephone interview data collected from a random sample of Midwestern U.S. women, supplemented by data from qualitative interviews, this admittedly exploratory article examines the complexities and ambiguities of demarcating the infertile from the fertile. We discuss the need for a more nuanced approach if we are to resolve some of the key questions in the social scientific study of infertility and show how we have dealt with these issues in our research.

The Question of Intent

Much research on the infertile in industrialized societies focuses on helpseekers, such as patients at infertility clinics, participants in IVF programs, or support group members. In the United States, where we conducted our research, helpseekers are a subset of the infertile with distinctive characteristics (Greil 1997). Therefore, insights from clinic samples do not automatically translate to the experiences of women who do not seek help for infertility. Women seeking help for infertility may be especially motivated toward having children and are likely to say that they are trying to get pregnant. Researchers working with infertility helpseekers are therefore likely to share with clinicians the presumption that intent to conceive is an integral and unambiguous part of the criteria for infertility. Women seeking help are also more likely to be middle-class women who have access to and are comfortable in medical-ized settings. Researchers working with infertility helpseekers are therefore likely to ignore the concerns of women who are excluded from these settings because of a lack of resources or who are uncomfortable or feel unwelcome in such settings. In most studies, therefore, the infertile are implicitly and inadvertently defined operationally as “people who ask for and receive infertility treatment.” Women who do not or cannot present themselves for treatment disappear from view.

As long as the study of infertility is limited to the study of clinic patients, conceptualizing who should be considered to be infertile seems unproblematic. But once we move beyond treatment seekers, we observe that those who are infertile according to the biomedical definition are a much more diverse group than often might be assumed; we encounter women who have experienced 12 months of unprotected intercourse but who say “no” to the question, “Are you trying to get pregnant?” Only when confronted with such women do we come face to face with the question of whether intent to become pregnant should be an explicit part of the definition of infertility.

If intent to conceive is to be considered part of the definition of infertility, our challenge becomes determining how strong, stable, and consistent intentions must be to qualify one as infertile. Many women are uncertain about their fertility intentions (Hagewen and Morgan 2005; Morgan 1982). Scholars of fertility and fertility intentions often leave those who are uncertain out of their analyses. Morgan (1982) posits that those who are uncertain about their fertility intentions are in a transitional phase between intending to have children and intending not to have children, but it may be that some of those who are uncertain are just less “planful” about their future fertility. Demographers and others often treat such concepts as “intended pregnancy” and “unintended pregnancy” as if these terms are clear and unambiguous, but qualitative research has shown that these are not emic categories that women spontaneously apply in describing their own pregnancies (Barrett and Wellings 2002). Many women are uneasy with classifying pregnancies as planned or unplanned (Finlay 1996). Moos et al. (1997) discovered that many of the lower socioeconomic status women who participated in their focus groups had difficulty finding meaning in the phrase “planned pregnancy.” Planfulness appears to be an essential component of contemporary notions of biological citizenship in industrialized societies. Women who do not plan either to become pregnant or not to become pregnant occupy a liminal status (Douglas 2002; Turner 1967) in terms of the cultural categories of biomedicine. These women, often those who are less privileged, are rendered problematic by a perspective that assumes planfulness.

Demographers sometimes treat fertility intentions as if they are stable “statelike” traits of an individual, but there is evidence that women change their fertility intentions over time with changing social contexts (Hayford 2009; Heaton et al. 1999; Lee 1980; Quesnel-Vallee and Morgan 2003). For example, few young women value a childfree lifestyle as a personal goal; rather, the expectation that one will have no children develops slowly through a series of short-term decisions (Bulcroft and Teachman 2004). Rather than understanding intentions as simply “out there,” we might do better to try to uncover the interpersonal, material, and cultural foundations out of which “intentions” are constructed (Holland et al. 1998). Fertility researchers often measure only women’s intentions and expectations (Greene and Biddlecom 2000), but it is important to consider possible differences between partners and the implicit and explicit negotiations that take place between partners (Miller et al. 2004; Thomson 1997; Voas 2003). For example, Zabin et al. (2000) showed that women’s stated birth intentions often vary from partner to partner.

The biomedical definition of infertility seems to assume that women are either trying to become pregnant or trying not to become pregnant. In this common-sense view, women who do not want to become pregnant use contraception, and a failure to use contraception consistently is taken as evidence that one is trying to become pregnant. Greenhall and Vessey (1990:978), however, point out that “couples often do not ‘test’ their fertility in the way implied by the standard definition. They use contraception intermittently or inefficiently and they change partners and the frequency of intercourse.” Abma et al. (1997) provide additional evidence of ambiguous intentions and inconsistent contraception when they report that 40 percent of pregnancies to U.S. women are unplanned (Abma et al. 1997). Here we encounter again the implicit assumption that women ought to plan. It is (usu.privileged) women who exercise control over their fertility who are envisaged as potential infertility patients. Less planful and, perhaps, less privileged women, often represented in the media as “hyperfertile” and irresponsible, are defined out of existence.

Looking beyond treatment seekers may help us to resolve a paradox that emerges from current social scientific research on infertility in industrialized societies. Studies of infertile women (Becker 2000; Greil 1991; Sandelowski 1993) usually describe infertility as an extremely distressing experience. Despite such strong evidence that infertility is distressing, only about half of women who fit the biomedical criteria for infertility seek treatment (Boivin et al. 2007). From the biomedical perspective, this discrepancy represents “unmet need,” and the most obvious action to pursue is patient education. It is possible, however, that the women who present themselves for treatment are different in striking ways from those who do not seek help. We suggest that one fundamental difference between these two groups involves self-defined fertility intentions.

To try to develop a “correct” definition of infertility entails making the kind of essentialist assumptions that are so central to biomedicine but tend to arouse suspicion among social scientists. A constructi vist perspective suggests that infertility is best seen as an identity category that women and men employ to make sense of their experience. Infertility is in effect a “claim” that one is entitled to treatment. Like all identity categories, the infertile label is more readily offered to some women than others. But if infertility is not an objective, clearly delineated category, how are we to study it? In our own research we have tried to employ ethnographically informed categories that are respectful of the lived worlds of the women we have studied. We do not propose the categories we employ as the “correct” way to conceptualize and categorize infertility. Rather, we see our categories as ideal types that have proven useful for our research purposes. We have employed more refined categories to assess when intention matters and when it does not. Our goal is to conceptualize meaningful fertility status categories that are appropriate for a random sample of women, and that do not artificially obscure important differences in intention and perspectives among women. In this article, we illustrate the range of motherhood intentions among a random sample of U.S. women, discuss categories constructed to respect differences among women and that reflect a continuum of fertility intentions, and describe three analyses that testify to the utility of these fertility status categories for several research purposes.

Methods

In developing our argument we rely on two sources of data, a telephone survey and in-person interviews. The survey was designed as a pilot project for a larger study of a random sample of U.S. women, now in progress. The methodology is described more fully elsewhere (McQuillan et al. 2003). The primary purpose of the in-person interviews was to refine the new survey instrument for the larger survey data collection effort. As we will discuss in greater detail below, data from the pilot study revealed the existence of a group of woman who had, at some point in their lives, experienced at least a year of unprotected intercourse without achieving a pregnancy but who did not describe themselves as having “tried” to get pregnant. The survey for this pilot study dictated that these women should receive the battery of infertility questions, but interviewers reported that some of these women found these questions to be inappropriate. We conducted the in-person interviews after the pilot study, then, to learn more about women who do not seek medical help for infertility or who meet infertility criteria but were not trying to get pregnant.

Through newspaper advertisements, posted announcements, and personal invitations, we recruited women who met the following criteria: (1) They had been trying to get pregnant for at least six months or they could have gotten pregnant during the last six months; (2) they were between the ages of 25 and 45; and (3) they had not sought medical help to get pregnant. The in-person interviews involved six women and two of their male partners, for a total of eight individuals. In the two cases where partners participated, we interviewed the couple as a unit. All of the interviews were conducted in person at the University of Nebraska and lasted between a half hour and two hours. Julia McQuillan, Lynn White, and a Bureau of Sociological Research interviewer conducted the interviews. We used probes to make sure the interviews covered a set of general questions, but for the most part we gave respondents free rein to talk about their experiences in a manner that seemed appropriate to them. All of the semistructured interviews were tape-recorded, and the tapes were transcribed. We do not attempt to generalize solely on the basis of these few interviews but, rather, use them in conjunction with the telephone survey data to clarify confusing results.

Categories of Fertility Status

As part of the telephone survey, women were asked a series of questions to ascertain their fertility goals and histories. Women were regarded as infertile if they reported one of three situations: they ever tried unsuccessfully to get pregnant for one year or more, they ever tried for 12 months or more to conceive any of their pregnancies, or they ever had one year or more of unprotected intercourse without pregnancy. We used a lifetime prevalence measure of infertility; women were classified as infertile if they had ever experienced a period in their lives when they fit the medical definition of infertility.

On the basis of these women’s answers to questions about their fertility status, we created six fertility status categories (see Table 1). Of the 580 women who were interviewed, 196 (34 percent) met the criteria for infertility at some point in their life and were asked questions about help seeking. Of the 196 infertile women from the telephone interview, 123 (63 percent) were classified as “infertile with intent to conceive” because they reported that they had tried for longer than 12 months to conceive. Two of the women we interviewed in-depth were comfortable describing themselves as “trying” to get pregnant and thus exemplify women in this category. One of them, a 27-year-old woman whom we will call Lillian,4 had been trying to conceive for about two years. Although she had not yet been to an infertility specialist because of financial reasons, she did not seem very different from the treatment seekers who have been the subject of most clinic-based research. Lillian described infertility as a challenge to her identity: “It’s almost to the point where like you know I can’t even feel being a woman fully without having children. So it really upsets me.” She wanted very much to have a baby, but she felt she was running out of time: “I really feel like my biological time clock is ticking. I just really, really would love to have a child, and I think that I’m at that point right now where I’m ready to call a doctor. It’s the money situation that [makes it so] I can’t.” Members of her church had counseled her that God would give her children when He was ready, but Lillian did not intend to let religious concerns stand in the way of treatment. As she put it, “God wouldn’t allow them to have the medicine if it wasn’t here for a reason.”

Table 1.

Fertility Status Categories, Criteria for Fertility Barriers (FB), and % with Fertility Specific Distress (FSD) Data

| Fertility status | Category Inclusion criteria | Total sample N and % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No fertility barriers | Did not meet criteria for any of the fertility barriers categories. | 227 | 39 |

| Infertile with intent to conceive | Tried to conceive (with regular unprotected intercourse) for > 12 months, with or without eventual conception. | 123 | 35 |

| “Infertile without intent to conceive” | Regular, unprotected intercourse for > 12 months with or without eventual conception (not trying). | 73 | 21 |

| Other infertility | Wanted children or more children, but self or partner had been sterilized, or had been told by MD not to conceive, or has a self-perception as having difficulty but did not meet medical criteria for infertility. | 38 | 11 |

| Miscarriage | Had at least one miscarriage and did not fit in another category. | 63 | 18 |

| Situational barriers | No biomedical fertility barriers, intend to have a child in the future, has 1 or fewer children, is at least 35 years old, and faced at least one of the following situations: partner doesn’t want a child, jobs makes it difficult, can’t afford a child, can’t find a partner. | 56 | 16 |

| Total N | 580 | 100 | |

Mercedes, a 27-year-old woman with a four-year-old child, also described herself as trying to get pregnant. Although she had not yet been “off the pill” for a full year, and, thus, does not meet the biomedical criterion for infertility, she would have presented herself for treatment had money not been a barrier. According to Mercedes:

We haven’t gone so far as to do the temperature with ovulation and all that kind of stuff. We just kind of count the days and try to time. So I think this last month I was probably the most disappointed, but I know that I don’t want to get myself worked up and worried about it, because I know that’s not a good thing. And we have so much going on right now that it’s like, well maybe, you know, it’s going to happen when it’s supposed to happen. There’s too much going on right now, and you know when we finally settle down is when it will come. So but you know [it’s] in the back of my mind that here’s it been six, seven, eight months and….

Mercedes described her sense of being a person with fertility problems as something that developed gradually:

In the beginning, I really didn’t think about until about once a month. Here in the past couple of months, my best friend just had a baby, about three weeks ago. And then my sister just had a baby too, and a girl at work just had a baby about a month ago. So it’s like, you know, I’ve been around all these babies, and so I think I tend to think about it a little more. And my four-year-old really helps remind me every day here lately because she is always talking about our new baby.

We classified as “infertile without intent to conceive” the remaining 73 (37 percent) women from the telephone interview sample who reported having unprotected intercourse for more than a year without pregnancy but who did not respond affirmatively to the other qualifying questions. The “infertile without intent to conceive” are, then, women who qualify as infertile according to the “12 months of unprotected intercourse” criterion but not according to the “intent” criterion. The “infertile without intent to conceive” were not voluntarily childless; in fact, 90 percent of them were biological mothers. Four of the women from the in-person interviews could be classified as “infertile without intent to conceive.” These women said they were not comfortable with the term trying.

Two of these women said that they had not tried and would not try to become pregnant because they saw pregnancy as something couples should be open to and accept but not try to achieve or prevent. They preferred to describe themselves as “hoping” to get pregnant. Katie, a 26-year-old woman with three children, and her husband Dan, age 27, had been married about six years when we interviewed them. Katie said that she and Dan had not used contraception during that period. According to Katie, “We didn’t really plan any of our children. So they have just been kind of a surprise or like a blessing…. I mean it’s not that we were totally shocked, because I guess I figure anybody that has sex ought to figure that that’s a potential (laughter)___But we just didn’t really intentionally think about it until it happened, I guess.” Dan concurred: “I just kind of let God do what he wants to do. And so if we are going to get pregnant, then we’ll get pregnant, because that’s in God’s plan.” Katie was hoping to become pregnant once more but did not plan to see a fertility specialist. As she put it, “If 1 hadn’t had any kids, then I would probably want to see a doctor, and I would probably do it, trying to meet God half way.” Jennifer, a 29-year-old mother of three, is another woman we would classify as “infertile without intent to conceive.” Jennifer concluded on the basis of discussions with friends about what the Bible has to say about children: that people should let the Lord decide how many children they should have. “We’re Christian,” she said, “Bible believing…. So we just really feel…that God blesses us and opens and closes the womb, and he has a plan for our family. And so we’re just excited about whatever that is.” Her husband Matt, also 29, said that he would like more children but that he did not have a specific number in mind: “Now I don’t want to quit. Because every time we have a child, it’s like, ‘What if we didn’t have this child? We would miss them.’”

Thirty-year-old Marta, a third woman who would fit into the “infertile without intent to conceive” category, reported having a very different attitude to becoming pregnant. Marta told us that she had been in a stable relationship for about three years, during which she regularly had intercourse without contraception. Thinking about it, she couldn’t really explain why she had not using birth control, because she was a graduate student at the time and did not want to have a child. She was also concerned about having a child with that partner. When we asked Marta how she felt when she got her period, she replied:

The sensation is relief. You know, because it wouldn’t have been the ideal situation, that’s for sure. It would have been a bad thing for the relationship; …it wasn’t a good relationship anyway. So there was always relief, but … a day would pass by, or two days would pass by, or the next time that we had sex, I would think about it. I’d think it’s kind of weird that I’ve never gotten pregnant, you know, and it’s been so long, you know, it’s just kind of strange that I never got pregnant.

Toward the end of her relationship with this man, she confided her concerns to her sister, who replied that God was having mercy on her and that she should be grateful she had not become pregnant. When we interviewed her, Marta was about to be married to a different man and told us that she would like to start trying to have a child soon after their marriage.

A fourth woman who fits into this category, Sarah, a 32-year-old graduate student, was married to a man who did not want children. At the time we interviewed her, Sara was back on birth control, but there had been a long period when neither she nor her husband were taking steps to avoid pregnancy. Sarah knew that, because she had endometriosis, her chances of getting pregnant were low. When asked if she thought of herself as infertile, Sarah responded as follows:

It was very much in passing, just sort of a thought that was on my mind, and I really only talked to about two people. I didn’t really explore it; it was a note that I made mentally and went on. So it was, “Hey, you know, so and so got pregnant. Oh, that’s great. Isn’t it interesting that all my friends get pregnant, and I don’t? Ah, you are probably just extra careful….” (laughter)

Our primary focus in this article is on the “infertile with intent to conceive” and the “infertile without intent to conceive.” The other fertility types are described in greater detail elsewhere (Jacob et al. 2007). It is, however, briefly worth drawing attention to the 56 women who acknowledged a situational barrier and were placed in the “situational barriers” group. Reported barriers included not being able to find a partner who also wants children, having a partner who does not want to have children, having a job that makes it too difficult to have children, not being able to afford children, and having postponed having children until it was too late. Although these women are not our primary focus here, the existence of such women provides further evidence that there are alternatives to the biomedical dichotomy of fertile versus infertile. The existence of these women highlights again the idea that fertility intentions are not characteristics of individuals that remain stable over time but, rather, culturally constructed realities that shift with changing circumstances. The question of how a woman comes to define a circumstance as a situational barrier is beyond the scope of this article.

We have been especially interested in the 73 “infertile without intent to conceive” women who reported that they had 12 months or more of unprotected intercourse without getting pregnant but did not say that they were trying to get pregnant at the time. These are precisely the women who would be counted as infertile in most epidemiological studies, but who are unlikely to be included in studies employing clinic samples. Only by paying attention to women meeting common definitions of infertility but who are not trying to conceive can we begin to unravel the relevance of fertility intent for understanding the identity, experiential, and behavioral concomitants of infertility.

The evidence collected through in-person interviews suggests that women meeting criteria for infertility but without intent to conceive are not a homogeneous group. One would be hard-pressed to decide where to draw the line between intention and no intention. What we see here is a continuum of intention, rather than clearly delineated categories. The categories we have constructed to guide us in our research must be understood as ideal types, rather than as ontological categories. To study the relationships among infertility, psychosocial outcomes, or help seeking, we classify women in terms of their fecundity status for specific analyses, but we make no claim that that there are “really” a certain number of fertility statuses. Instead, we argue that fertility statuses are ambiguous and that no criterion can clearly demarcate the infertile from the noninfertile.

Motherhood Intentions among Nonmothers

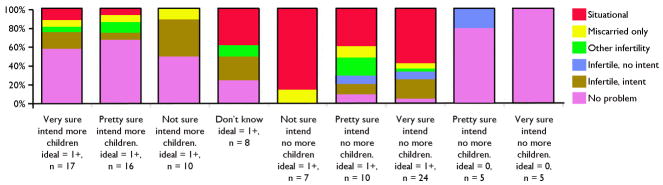

Another way to examine the question of intent is to look at what women without children tell us about their desires and intentions with regard to motherhood. The telephone survey included three questions that allowed us to assess infertility intentions among women without children (n = 102). One question asked each woman to select the ideal number of children she would like to have if she could choose freely. For the purposes of this analysis, we divided women into those whose ideal number of children is zero and those whose ideal number of children is greater than zero. A second question asked women whether or not they intended to have a baby, and a third question asked them how sure they were about their previous answer. One might expect that all women without children whose ideal number of children is greater than zero would say that they intended to have a baby, but – as Table 2 and Figure 1 show – virtually every logically possible combination of ideals, intent, and certainty were represented among our sample.

Table 2.

Distribution of Fertility Status and Mean Value of Motherhood by Intention Status Among Women without Children

| Ideal = 1 or more children | Ideal = 0 children | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Very sure intend children | Pretty sure intend children | Not sure intend children | Don’t know | Not sure intend no children | Pretty sure intend no children | Very sure intend no children | Pretty sure intend no children | Very sure intend no children | |

| (n = 17) | (n = 16) | (n= 10) | (n = 8) | (n = 7) | (n= 10) | (n = 24) | (n = 5) | (n = 5) | |

| No problem | 58.82 | 68.75 | 50 | 25 | 0 | 10 | 4.17 | 80 | 100 |

| Infertile, intent | 17.65 | 6.25 | 40 | 25 | 0 | 10 | 20.83 | 0 | 0 |

| Infertile, no intent | 5.88 | 12.5 | 0 | 12.5 | 0 | 10 | 8.33 | 0 | 0 |

| Other infertility | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 4.17 | 20 | 0 |

| Miscarried only | 5.88 | 6.25 | 10 | 0 | 14.29 | 10 | 4.17 | 0 | 0 |

| Situational barrier only | 11.76 | 6.25 | 37.5 | 85.71 | 40 | 58.33 | 0 | 0 | |

| Valuing motherhood scale (0–3) | 2.37 | 2.06 | 2.08 | 1.58 | 1.79 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.5 | 1.2 |

Figure 1.

Fertility Ideals and Intentions by Fertility Status Category among Women without Children.

Ten women stated that their ideal number of children was zero and that they were either “very sure” or “pretty sure” they will not have children. These ten women can be safely categorized as “childfree” or “voluntarily childless.” None of these women reported any type of fertility problem. At the other end of the continuum, 33 women said they were very sure or pretty sure that they intended to have a child. Of these 43 women at either end of the continuum, 63.6 percent had no fertility problem, 12.1 percent were classified as “infertile with intent to conceive,” whereas 9.1 percent were “infertile without intent to conceive.” That leaves 59 women at various spots in the center of the scale indicating a lack of certainty about their fertility intentions. The middle of the continuum includes women from every one of the six categories of fertility status to which we assigned women.

Evidence that the continuum of fertility intentions is, in fact, a continuum can be found through an examination of the relationship between fertility intention status and a five-item importance of motherhood scale we developed. Table 2 includes mean importance of motherhood scores for all nine categories of infertility intention. Importance of motherhood is a unidimensional, five-item scale (α = .72) that taps the importance of motherhood as a life identity. Examples of statements included in the scale are “Having children is important to my feeling complete as a woman,” and “I think my life will be or is more fulfilling with children.” Those at the low end of the fertility intention scale have the lowest scores for importance of motherhood, those at the high end of the scale reported the highest levels of importance of motherhood, and those in the middle on the fertility intention scale are in the middle on the scale. On neither scale is it possible to discern any obvious line that divides those who intend to have children from those who do not, nor those who consider motherhood important from those who do not. What we see instead are gradations in levels of fertility intention and importance of motherhood.

The “Infertile without Intent to Conceive”: Some Relevant Findings

To illustrate both the utility of paying greater attention to fertility intentions and of extending our research to include nonhelpseekers, we summarize several analyses we have carried out using the data from the telephone survey. We wish to show how paying attention to the complexities and ambiguities of infertility status has informed our analysis and led to important conclusions about responses to infertility that we might well have missed had we employed a simple “infertile-not infertile” dichotomy. In particular, we consider the “infertile without intent to conceive” a group of women who deserve to be studied in their own right.

We first discuss a study (Greil and McQuillan 2004) that compared help seeking separately among the infertile with and without intent to conceive. We found that the “infertile without intent to conceive” tended to be younger and have less family income than the “infertile with intent to conceive.” Although parenthood status did not differ between the two groups, the “infertile without intent to conceive” were less likely to be married, to want another child, and to think of themselves as having fertility problems. They were also less likely to report engaging in a wide range of information-seeking or self-education activities.

The finding that these two groups had distinctive characteristics supported our decision to analyze treatment-seeking patterns separately by type of infertility. We also found that those with intent to conceive were much more likely to seek help, and among those who sought help, they were much more likely to receive treatment. Nevertheless, it is interesting that 14 percent of women who did not see themselves as trying to conceive still sought medical help for pregnancy. We speculated that the “infertile without intent to conceive” may have a more passive or fatalistic approach to parenthood than the “infertile with intent to conceive.” This seems supported by data from the in-person interviews.

In another study (White et al. 2006), we used logistic regression to examine self-identifying as infertile and help seeking for infertility as a two-step process. Controlling for all other variables in the model, women who experienced infertility with intent to conceive were eight times more likely to perceive a fertility problem than women who were “infertile without intent to conceive.” In addition, infertile women with intent to conceive were significantly and substantially more likely to have sought help. Perception of infertility as a problem was a significant mediating variable between other help-seeking predictors and help seeking only among the “infertile with intent to conceive.” Although these conclusions may seem obvious and logical, if we had only used the medical criteria for infertility, we would have missed the importance of intentions and would have underestimated these effects. If we had only examined those with intent to conceive, we would have obtained a picture similar to clinic sample findings, but we would not have gotten the message that some women experience infertility very differently from those in clinic populations, not just because they do not have access to treatment, but also because they have weaker or different fertility intentions.

Having established that the infertile with and without intent to conceive differ in some important ways with regard to help seeking, we turn now to the relationship between fertility status and the psychosocial consequences of infertility. In our earliest study based on the pilot data, we assessed the association between infertility and general psychological distress (McQuillan et al. 2003), comparing three fertility status categories: the infertile, the “other infertility” group, and the “no fertility problem” group. Our main finding was that infertility is associated with significantly higher long-term distress only for those who are not either biological or social parents. We interpreted the strong, long-term effect of involuntary childlessness as supporting the argument that frustrated attempts to achieve motherhood threaten a central life identity. When we reanalyzed the data, separating out the “infertile with intent to conceive” from those without intent to conceive, we found that the effects of infertility on general psychological distress are similar for both the “infertile with intent to conceive” and the “infertile without intent to conceive.” It is, of course, possible that a distress measure specific to infertility might have uncovered differences between these two groups.

What we find most interesting about the telephone survey data is that, in some ways, those with and without intent to conceive are very similar, while in other ways they are very different. When we study infertility help seeking, we find that the “infertile without intent to conceive” behave very differently from the “infertile with intent to conceive.” They are less likely to see themselves as having a fertility problem, and they are much less likely to seek and to receive treatment. We might be inclined to conclude that the “infertile without intent to conceive” should be excluded from the category of the infertile altogether were it not for the fact that the “infertile without intent to conceive” respond very similarly to the “infertile with intent to conceive” when it comes to psychological distress. Thus, it would be a mistake to leave the “infertile without intent to conceive” out of our analysis, because they seem to experience the same emotional consequences of infertility as do those with intent to conceive. At the same time, it would be a mistake to lump the “infertile without intent to conceive” together with “infertile with intent to conceive,” because they can interpret their infertility so differently and respond to it so differently.

Conclusion

Studies of infertile women in industrialized societies that focus on clinic samples or samples of women who have sought and received treatment do not reveal the experiences of nonhelpseekers. The world of the infertility clinic often serves as a backdrop for much of what we think we know about infertility. The subjects of much infertility research are biological citizens who come to the clinic feeling that biomedical treatment is appropriate for them, and they are reinforced in this belief once they arrive. Because treatment is voluntary, some prefiguring in the direction of the biomedical model will have already taken place, even before entering the clinic. Because treatment is time consuming, costly, and invasive, a strong intent to become pregnant characterizes most infertility patients. Because assisted reproduction is economically and racially stratified, only women with a strong desire to become pregnant, women who have the resources to afford treatment, and women who feel comfortable in biomedical settings will become patients.

Thus, a research focus on those who visit infertility clinics renders invisible the experiences of women who have not sought treatment, either because they do not feel they have access to the resources of biomedicine or because they do not identify as infertile or do not see their situation in medicalized terms. A focus on treatment seekers not only ignores the experiences of half of U.S. women who are infertile by the medical definition, but it takes for granted the biomedical concept of “infertility” without subjecting that concept to a close examination. The implicit definition of the infertile both in medical practice and in much social scientific research is “anyone who shows up at the clinic.” Although intention to become pregnant is not a formal part of the biomedical definition, it appears to be taken for granted.

Once we go beyond the clinic setting, we trade a spurious definitional certainty for complexity, ambiguity, and questions about intentionality. Women cannot be easily divided into those who intend to become pregnant and those who do not. Not all women who have had unprotected intercourse for a period of 12 months or longer see themselves as having tried to get pregnant. Nor do all women who meet the medical criterion for infertility acknowledge that they have or have had a fertility problem. Taking intention status into account does much to illuminate the experience of infertile women. Our research suggests that an adequate social scientific approach to infertility needs to recognize that infertility is a socially constructed phenomenon. Attempts to delineate the infertile from the noninfertile or to understand the experience of infertility are less likely to be successful if they do not attend to the lived experience and self-definition of actors.

It is difficult to know if “intent” and “no intent” precede behavior or if they are retrospective constructions of past events. Longitudinal data will provide a way to assess whether fertility intentions change as social contexts change. We have not been able to observe women in the process of constructing infertile identities either in the context of their everyday lives or in the context of their encounters with the world of the infertility clinic. We have not been able to observe the ways in which stratified reproductive pathways shape the intentions, identities, and behaviors of the women in our sample. It is important to look at women before they enter the world of fertility treatment as well as after to access the impact of those encounters. Only then will we know to what extent women learn infertile identities in the treatment context and to what extent that identity has already taken shape before they arrive. Only then can we know if intention to become pregnant is a prerequisite for seeking infertility treatment or if intention to become pregnant is intensified by the experience of treatment. With multiple observations on the same women over time, we will be close to answering whether self-identity helps to explain why some women seek help and others do not, or whether self-identity is constructed primarily in the clinic context. At present we cannot know if women who do not seek treatment have a construction of their situation that is at odds with the moral economy of biomedicine or if they are simply unaware that their situation meets the criteria for infertility. We are currently collecting data for a longitudinal study that will allow us to watch women change as they discover their infertility and come to identify as infertile (or not).

Even longitudinal survey data, however, cannot replace the thick description of ethnographic research. Our survey is built on qualitative research but sacrificed depth for greater generalizability. We have tried to bring an ethnographic sensibility to the tasks of developing our concepts and of trying to make sense out of our results. We have not tried to replace the biomedical definition of infertility with our own, “better” definition. To do so would be to fall into the same essentialism for which we have criticized the biomedical definition. Our goal, rather, has been to sensitize anthropologists and other social scientists to the issue of intentions that the biomedical definition has obscured. Although much theory and research begins with the assumption that the infertile are a unitary group, our research has convinced us that differences among the infertile, especially differences in fertility intention status and in the perception of a fertility problem, are crucial for understanding both the psychological consequences of infertility and patterns of help seeking. As we move from convenience-based clinic samples to population-based studies, we will discover that the relatively neglected issues of parenthood intentions and self-definition take on increased importance.

Footnotes

Infertility can affect both women and men. Because this article refers to research about women, we employ the term women, rather than women and men or couples to refer to those with infertility.

Most Internet web sites define infertility more simply as failure to conceive after 12 months of unprotected intercourse. This definition has been used by the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) in the United States and by researchers in the Netherlands, Norway, and other industrialized societies (Schmidt and Münster 1995). There is not, however unanimous agreement about the 12-month cutoff. The World Health Organization (WHO) considers a couple to be infertile if they have experienced two years of unprotected intercourse, and some demographers have used longer intervals of either five or seven years (Larsen 2000). The justification offered for use of longer intervals is that this allows demographers to be as certain as possible that only women who are extremely unlikely to ever conceive will be classified as infertile.

Studies of the experience of infertility among members of racial minority groups (see Becker et al. 2005; Culley et al. 2006; Inhorn and Fakih 2006) suggest that, although the psychosocial response to infertility among these groups is similar in many ways to the response of more frequently studied groups, minority women feel that they have equal access to infertility treatment. Thus, race differences in infertility help seeking cannot be assumed to be because of race differences in the personal and social experience of infertility. The NSFG has documented race disparities in infertility help seeking (Stephen and Chandra 2000). Of 31,047 women interviewed between 1982 and 2002, 15.8 percent of white women reported ever having received treatment for infertility as compared to 10.7 percent of black women and 12.2 percent of Hispanic women.

All of the participant names used in this article are pseudonyms.

Contributor Information

Arthur L. Greil, Division of Social Sciences, Alfred University

Julia McQuillan, Department of Sociology, University of Nebraska Lincoln.

References

- Abma Jill, Chandra Anjani, Mosher William A, Peterson Linda S, Piccinino Linda J. Fertility, Family Planning, and Women’s Health: New Data from the 1995 National Survey of Family Growth. National Center for Health Statistics. Vital and Health Statistics. 1997;23(19):1–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Definitions of Infertility and Recurrent Pregnancy Loss. Fertility and Sterility. 2008;90:S60. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.08.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett Geraldine, Wellings Kaye. What Is a “Planned” Pregnancy? Empirical Data from a British Study. Social Science and Medicine. 2002;55(4):545–557. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00187-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker Gay. The Elusive Embryo: How Women and Men Approach New Reproductive Technologies. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Becker Gay, Castrillo Martha, Jackson Rebecca, Nachtigall Robert D. Infertility among Low-Income Latinos. Fertility and Sterility. 2005;85(4):882–887. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.09.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell Ann. MA thesis. Department of Sociology, University of Michigan; 2009. Beyond (Financial) Accessibility: Inequalities within the Medicalization of Infertility. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boivin Jacky, Bunting Laura, Collins John A, Nygren Karl G. International Estimates of Infertility Prevalence and Treatment-Seeking: Potential Need and Demand for Infertility Medical Care. Human Reproduction. 2007;22:1506–1506. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulcroft Richard, Teachman Jay. Ambiguous Constructions: Development of a Childless or Childfree Life Course. In: Coleman Marilyn, Ganong Lawrence H., editors. Handbook of Contemporary Families. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 2004. pp. 116–135. [Google Scholar]

- Colen Shellee. With Respect and Feelings: Voices of West Indian Childcare and Domestic Workers in New York City. In: Cole Johnetta B., editor. All American Women: Lines that Divide, Ties that Bind. New York: Free Press; 1986. pp. 46–70. [Google Scholar]

- Conrad Peter, Schneider Joseph W. The Medicalization of Deviance: From Badness to Sickness. St. Louis: Mosby; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Culley Lorraine A, Hudson Nicky, Rapport Frances L, Katbamna Savita, Johnson Mark RD. British South Asian Communities and Fertility Services. Human Fertility. 2006;9(1):37–45. doi: 10.1080/14647270500282644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daston Lorraine. Moral Economy of Science. Osiris. 1995;10:3–26. [Google Scholar]

- Davis-Floyd Robbie. Birth as an American Rite of Passage. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Douglass Mary. Purity and Danger: An Analysis of the Concepts of Pollution and Taboo. London: Routledge; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman-Savelsberg Pamela. Plundered Kitchens, Empty Wombs: Threatened Reproduction and Identity in the Cameroon Grassfields. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Finlay Andrew. Teenage Pregnancy, Romantic Love, and Social Science: An Uneasy Relationship. In: James Veronica, Gabe Jonathan., editors. Health and Sociology of the Emotions. Oxford: Blackwell; 1996. pp. 79–96. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin Sarah. Embodied Progress: A Cultural Account of Assisted Conception. London: Routledge; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Greene Margaret E, Biddlecom Anne E. Absent and Problematic Men: Demographic Accounts of Male Reproductive Roles. Population and Development Review. 2000;26(1):81–115. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhall Elizabeth, Vessey Martin. The Prevalence of Subfertility: A Review of the Current Confusion and a Report of Two New Studies. Fertility and Sterility. 1990;54(6):978–983. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)53990-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greil Arthur L. Not Yet Pregnant: Infertile Couples in Contemporary America. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Greil Arthur L. Infertility and Psychological Distress: A Critical Review of the Literature. Social Science and Medicine. 1997;45(11):1679–1704. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00102-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greil Arthur L, McQuillan Julia. Help-Seeking Patterns among U.S. Women. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology. 2004;22(4):305–319. [Google Scholar]

- Hagewen Kellie J, Philip Morgan S. Intended and Ideal Family Size in the United States, 1970–2002. Population and Development Review. 2005;31(3):507–527. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2005.00081.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handwerker Lisa. The Hen That Can’t Lay an Egg (Bu xia dan de mu ji): Conceptions of Female Infertility in Modern China. In: Terry Jennifer, Urla Jacqueline., editors. Deviant Bodies: Critical Perspectives on Difference in Science and Popular Culture. Bloomington: Indiana University Press; 1995. pp. 358–379. [Google Scholar]

- Hayford Sarah R. Evolution of Fertility Expectations over the Life Course. Demography. 2009;46(4):765–783. doi: 10.1353/dem.0.0073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton Timothy B, Jacobson Cardell J, Holland Kimberlee. Persistence and Change in Decisions to Remain Childless. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1999;61(3):531–539. [Google Scholar]

- Herzlich Claudine, Pierret Janine. Illness and Self in Society. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch Jennifer. Culture. Long-Range Planning Report, National Institutes of Health. [accessed February 26, 2010.];Electronic document. 1998 http://0-www.nichd.nih.gov.library.unl.edu/about/meetings/2001/DBS_planning/hirschl.cfm.

- Holland Dorothy C, Lachicotte William, Jr, Skinner Debra, Cane Carole. Identity and Agency in Cultural Worlds. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hollos Marida. Problems of Infertility in Southern Nigeria: Women’s Voices from Amakiri. African Journal of Reproductive Health. 2003;7:46–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inhorn Marcia C. Quest for Conception: Gender, Infertility, and Egyptian Medical Traditions. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Inhorn Marcia C. Infertility and Patriarchy: The Cultural Politics of Gender and Family Life in Egypt. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Inhorn Marcia C. Defining Women’s Health: A Dozen Messages from More than 150 Ethnographies. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 2006;20(3):345–378. doi: 10.1525/maq.2006.20.3.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inhorn Marcia C, Bharadwaj Aditya. Reproductively Disabled Lives: Infertility, Stigma, and Suffering in Egypt and India. In: Ingstad Bendicte, Whyte Susan Reynolds., editors. Disability in Local and Global Worlds. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2008. pp. 78–106. [Google Scholar]

- Inhorn Marcia C, Birenbaum-Carmeli Daphne. Assisted Reproductive Technologies and Culture Change. Annual Review of Anthropology. 2008;37:177–196. [Google Scholar]

- Inhorn Marcia C, Fakih MH. Arab Americans, African Americans, and Infertility: Barriers to Reproduction and Medical Care. Fertility and Sterility. 2006;85(4):844–852. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacob Mary Casey, McQuillan Julia, Greil Arthur L. Psychological Distress by Type of Fertility Barrier. Human Reproduction. 2007;22:885–894. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen Ulla. Primary and Secondary Infertility in Sub-Saharan Africa. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2000;29(2):285–291. doi: 10.1093/ije/29.2.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Ronald D. Aiming at a Moving Target: Fertility and Changing Reproductive Goals. Population Studies. 1980;34(2):205–226. doi: 10.1080/00324728.1980.10410385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard Lori. “Looking for Children”: The Search for Fertility among the Sara of Southern Chad. Medical Anthropology. 2002;21(1):79–112. doi: 10.1080/01459740210618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lock Margaret. The Tempering of Medical Anthropology: Troubling Natural Categories. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 2001;15(4):478–192. doi: 10.1525/maq.2001.15.4.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin Emily. The Woman in the Body: A Cultural Analysis of Reproduction. Boston: Beacon; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- McQuillan Julia, Greil Arthur L, White Lynn, Jacob Mary Casey. Frustrated Fertility: Infertility and Psychological Distress among Women. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2003;65(4):1007–1019. [Google Scholar]

- Miller Warren B, Severy Lawrence J, Pasta David J. A Framework for Modeling Fertility Motivation in Couples. Population Studies: A Journal of Demography. 2004;58(2):193–205. doi: 10.1080/0032472042000213712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishler Elliot G, Amarasingham Lorna R, Osherson Samuel D, Hauser Stuart T, Waxier Nancy E, Liem Ramsay. Social Contexts of Health, Illness, and Patient Care. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Moos Merry-K, Petersen Ruth, Meadows Katherine, Melvin Cathy L, Spitz Alison M. Pregnant Women’s Perspectives on Intendedness of Pregnancy. Women’s Health Issues. 1997;7(6):385–391. doi: 10.1016/s1049-3867(97)00081-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan S Philip. Parity-Specific Fertility Intentions and Uncertainty: The United States, 1970 to 1976. Demography. 1982;19:315–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nachtigall Robert D. International Disparities in Access to Infertility Services. Fertility and Sterility. 2005;85(4):871–874. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.08.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pashigian Melissa J. Conceiving the Happy Family: Infertility and Marital Politics in Northern Vietnam. In: Inhorn Marcia C, van Balen Frank., editors. Infertility around the Globe: New Thinking on Childlessness, Gender, and Reproductive Technologies: A View from the Social Sciences. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2002. pp. 134–151. [Google Scholar]

- Quesnel-Vallee Amelie, Philip Morgan S. Missing the Target? Correspondence of Fertility Intentions and Behavior in the US. Population Research and Policy Review. 2003;22(5–6):497–525. [Google Scholar]

- Rapp Rayna. Gender, Body, Biomedicine: How Some Feminist Concerns Dragged Reproduction to the Center of Social Theory. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 2001;15(4):466–t77. doi: 10.1525/maq.2001.15.4.466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose Nikolas, Novas Carlos. Biological Citizenship. In: Ong A, Collier SJ, editors. Global Assemblages: Technology, Politics, and Ethics as Anthropological Problems. Maiden, MA: Blackwell; 2005. pp. 439–463. [Google Scholar]

- Rothman Barbara Katz. Recreating Motherhood: Ideology and Technology in a Patriarchal Society. New York: Norton; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe Patrick J, Comhane Frank J, Hargreave Timothy B, Mahmoud Ahmed MA. WHO Manual for the Standardized Investigation, Diagnosis, and Management of the Infertile Male. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski Margarete. With Child in Mind: Studies of the Personal Encounter with Infertility. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski Margarete, de Lacey Sheryl. The Use of a “Disease:” Infertility as a Rhetorical Vehicle. In: Inhorn MC, van Balen F, editors. Infertility around the Globe: New Thinking on Childlessness, Gender, and Reproductive Technologies: A View from the Social Sciences. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2002. pp. 33–51. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt Lone, Münster Kirstine. Infertility, Involuntary Infecundity, and the Seeking of Medical Advice in Industrialized Countries 1970–1992: A Review of Concepts, Measurements, and Results. Human Reproduction. 1995;10(6):1407–1418. doi: 10.1093/humrep/10.6.1407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephen Elizabeth Hervey, Chandra Anjali. Use of Infertility Services in the United States: 1995. Family Planning Perspectives. 2000;32(3):132–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson Charis. Making Parents: The Ontological Choreography of Reproductive Technologies. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Thomson Elizabeth. Couple Childbearing Desires, Intentions, and Births. Demography. 1997;34(3):343–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner Victor. The Forest of Symbols: Aspects of Ndembu Ritual. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- van Balen Frank, Gerrits Trudie. Quality of Infertility Care in Poor-Resource Areas and the Introduction of New Reproductive Technologies. Human Reproduction. 2001;16(2):215–219. doi: 10.1093/humrep/16.2.215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voas David. Conflicting Preferences: A Reason Fertility Tends to Be Too High or Too Low. Population and Development Review. 2003;29(4):627–646. [Google Scholar]

- White Lynn, McQuillan Julia, Greil Arthur L, Johnson David R. Infertility: Testing a Helpseeking Model. Social Science and Medicine. 2006;64(4):1031–1041. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whyte Susan Reynolds. Health Identities and Subjectivities: The Methodological Challenge. Medical Anthropology Quarterly. 2009;23(1):6–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1548-1387.2009.01034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabin Laurie Schwab, Huggins George R, Emerson Mark R, Cullins Vanessa E. Partner Effects on a Woman’s Intention to Conceive: “Not with This Partner”. Family Planning Perspectives. 2000;32(l):39–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]