Abstract

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) has a relatively large and complex genome, a protracted lytic replication cycle, and employs a strategy of replicational latency as part of its lifelong persistence in the infected host. An important form of gene regulation in plants and animals revolves around a type of small RNA known as microRNA (miRNA). miRNAs can serve as major regulators of key developmental pathways, as well as provide subtle forms of regulatory control. The human genome encodes over 900 miRNAs, and miRNAs are also encoded by some viruses, including HCMV, which encodes at least 14 miRNAs. Some of the HCMV miRNAs are known to target both viral and cellular genes, including important immunomodulators. In addition to expressing their own miRNAs, infections with some viruses, including HCMV, can result in changes in the expression of cellular miRNAs that benefit virus replication. In this review, we summarize the connections between miRNAs and HCMV biology. We describe the nature of miRNA genes, miRNA biogenesis and modes of action, methods for studying miRNAs, HCMV-encoded miRNAs, effects of HCMV infection on cellular miRNA expression, roles of miRNAs in HCMV biology, and possible HCMV-related diagnostic and therapeutic applications of miRNAs.

Keywords: herpesvirus, human cytomegalovirus, cytomegalovirus, human herpesvirus 5, microRNA, mammalian target of rapamycin

1. Introduction

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV; Human herpesvirus 5) is a herpesvirus; it has a relatively large and complex genome, a protracted lytic replication cycle, and employs a strategy of replicational latency as part of its lifelong persistence in the infected host. The complex lytic and latent phases are dependent on the ability of the virus to regulate many aspects of host immune responses and cell biology. The major societal burdens imposed by HCMV are the direct costs and sequelae associated with congenital infections and pathogenic viral activity in patients immunocompromised due to either AIDS or organ transplant-associated immunosuppression (Pass, 2001). In addition, evidence is accumulating that the virus may play a role in the development of inflammation-linked vascular diseases such as atherosclerosis (Reinhardt et al., 2002). Although numerous tools are available, improved diagnostic tools and therapeutic interventions are needed.

An important form of gene regulation in plants and animals revolves around a type of small RNA known as microRNA (miRNA). miRNAs can serve as major regulators of key developmental pathways, as well as provide subtle forms of regulatory control. miRNAs provide the target specificity for machinery that is most often employed to down-regulate translation of protein-coding mRNAs. In addition, miRNAs sometimes up-regulate translation and they can regulate transcription. The human genome encodes over 900 miRNAs, and miRNAs are also encoded by some viruses, including HCMV. miRNA activity can be regulated at many levels (biogenesis through end-point activities) and in response to a vast array of signals. In addition to expressing their own miRNAs, infections with some viruses, including HCMV, can result in changes in the expression of cellular miRNAs.

In this review, we summarize the connections between miRNAs and HCMV biology. We will describe the nature of miRNA genes, miRNA biogenesis and modes of action, methods for studying miRNAs, HCMV-encoded miRNAs, effects of HCMV infection on cellular miRNA expression, roles of miRNAs in HCMV biology, and possible HCMV-related diagnostic and therapeutic applications of miRNAs.

2. miRNAs: genes, biogenesis, and activity

Because the focus of this review is on the relationship between HCMV and miRNAs, we are taking the liberty of citing recent reviews for much of the background information on miRNAs.

Genes for the >900 human miRNAs are present on all but the Y chromosome (Griffiths-Jones, 2004; Shomron et al., 2009). Most miRNAs derive from 5′ capped and 3′ polyadenylated transcripts generated by RNA polymerase II. miRNA transcription is regulated by conventional regulatory mechanisms that enable individual miRNA primary transcripts to be expressed in response to diverse signals; these include particular transcription factor binding sites in promoter/regulatory regions of miRNA genes, and epigenetic mechanisms such as DNA methylation and histone modifications (Alexiou et al., 2009; Newman and Hammond, 2010). For example, p53 and c-myc can regulate miRNA gene transcription via binding to their cognate sequences present in some miRNA gene promoter/regulatory regions. miRNA can be expressed from genes whose primary product is one or multiple miRNA (miRNA clusters), and from the exons or introns of protein-coding genes. Approximately 60% of human miRNAs are expressed singly, 15% from clusters, and 25% from introns (Olena and Patton, 2010; Shomron et al., 2009).

miRNAs are formally denoted by their host organism (hsa for Homo sapiens) and a numeric designator. In instances where two miRNA derive from the same pre-miRNA, the less abundant species (at least under the conditions of the initial characterization) is designated with an asterisk, and is known as a “star” species. An example is hsa-miR-32 and hsa-miR-32*. In common use, the host designation is often dropped (e.g., miR-32).

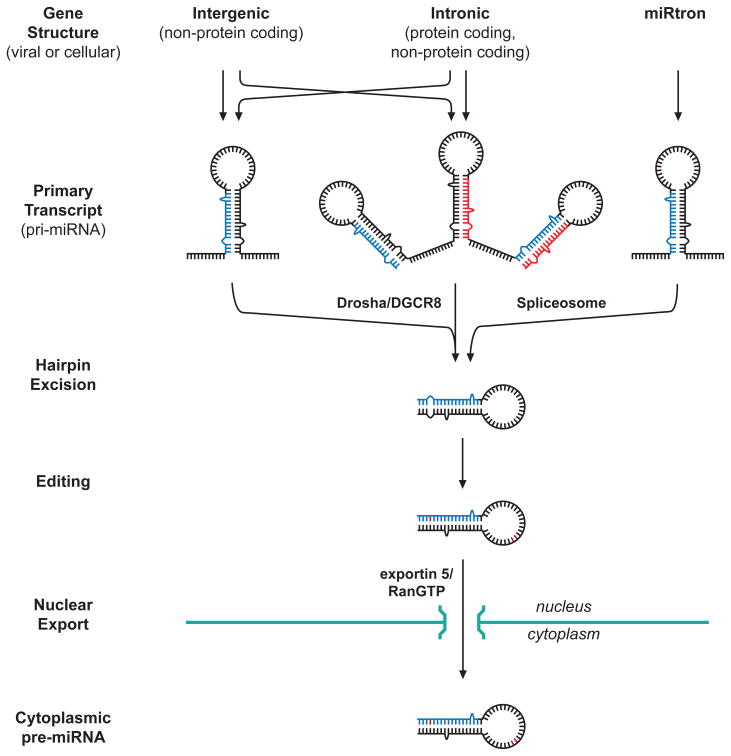

A defining aspect of miRNAs is that the primary transcript harbors a sequence capable of forming an imperfectly base-paired hairpin that has a stalk of ~22 bp and a single-stranded loop of ~25 nt (Breving and Esquela-Kerscher, 2009; Newman and Hammond, 2010) (Fig. 1). While still in the nucleus, the ~70 nt hairpin structure is cleaved from the primary miRNA transcript (pri-miRNA) by the microprocessor to form the pre-miRNA. The microprocessor is a complex that consists of Drosha (a type-III RNase) and DGCR8 (DiGeorge syndrome critical region 8 protein), plus other components. For some miRNAs, known as mirtrons, the hairpin is encoded as an intron, with hairpin excision occurring during splicing.

Fig. 1.

miRNA biogenesis: nuclear events. The major features of miRNA biogenesis are similar, regardless of whether the miRNA is encoded on the host or virus genome. Pri-miRNAs that arise from intergenic or intronic transcripts can harbor single or multiple hairpins that are each excised by Drosha/DGCR8. Hairpins arising from miRtrons are excised in the spliceosome via splice signals located near the base of the stem-loop structure. After editing (indicated as red bases), hairpins are exported by exportin 5/RanGTP through nuclear pores to the cytoplasm for subsequent processing (Fig. 2). RNA segments corresponding to mature miRNAs are indicated in red and blue.

A subset of miRNAs are edited posttranscriptionally by deaminating enzymes that convert adenosine to inosine, thereby possibly altering the specificity or mechanism of subsequent molecular interactions (Breving and Esquela-Kerscher, 2009). The process can be cell-type specific, can occur in the loop region and affect activities in the microprocessor, or can occur in the seed sequence (defined below), thereby altering target specificity.

Nuclear-to-cytoplasmic transport of the pre-miRNA stem-loop structure is generally via the Exportin-5/Ran-GTP pathway (Stewart, 2009). 5′ caps and 3′ polyadenylated sequences are removed from pri-miRNAs during Drosha/DGCR8 processing or splicing-associated hairpin excision, which could render the nascent pre-miRNA susceptible to degradation. Exportin-5 protects the deprotected 5′ and 3′ ends of the pre-miRNAs from degradation during transport from the nucleus.

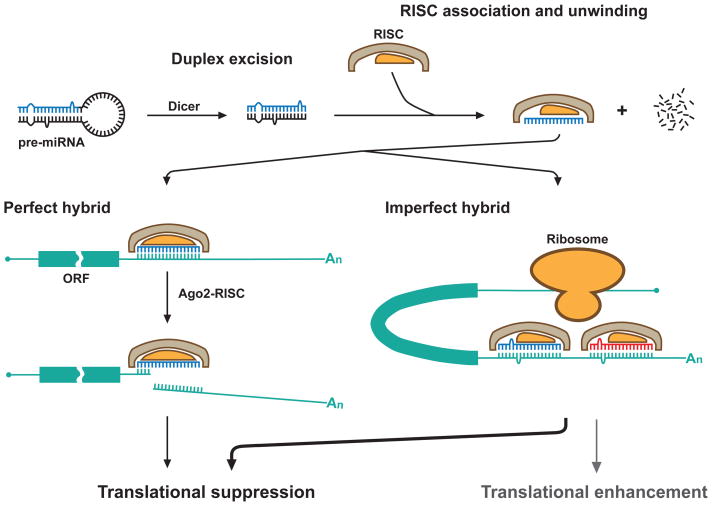

In the cytoplasm (Fig. 2), the loop is removed from the pre-miRNA by a complex that includes another type III RNase, Dicer (Breving and Esquela-Kerscher, 2009). This liberates a duplex RNA of ~22 nt, one strand of which (the mature miRNA, sometimes called the guide strand) is loaded onto the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC). The other strand is degraded. In most instances, one strand of the duplex is the preferred functional miRNA, but as mentioned above, there are instances where both strands can function independently as miRNAs that would target different sequences (one of the strands being designated as the “star” strand).

Fig. 2.

miRNA biogenesis and activity: cytoplasmic events. RNA segments corresponding to mature miRNAs are indicated in red and blue. As indicated, the major path of miRNA activity involves imperfect miRNA/mRNA hybrids and results in translational suppression.

The RISC includes one of the four human members of the argonaute protein family (Ago1–4/eIF2C) (Breving and Esquela-Kerscher, 2009). Ago2 is responsible for the “slicer” activity required for cleavage of the target mRNA in the event of perfect complementarity between the miRNA and its target. The other argonaute proteins contribute to translational silencing by other mechanisms. Although many details remain to be learned, these mechanisms include inhibition of translation initiation by blocking mRNA cap-binding by eukaryotic initiation factor 4E (eIF4E), reduced translational processivity, and increased ribosomal drop-off.

miRNA biogenesis can be shaped by interactions of pre-miRNAs with loop-interacting factors (Breving and Esquela-Kerscher, 2009; Newman and Hammond, 2010). LIN-28 is a protein that recognizes and binds to the stem-loop structure of the let-7 miRNA (let-7 was one of the first two microRNAs to be discovered and has retained its original name). In the nucleus, LIN-28 inhibits interaction of the let-7 pre-miRNA with the Drosha complex; in the cytoplasm, LIN-28 blocks Dicer cleavage of the let-7 precursor and also triggers terminal uridylation of the let-7 pre-miRNA, which targets the RNA for degradation.

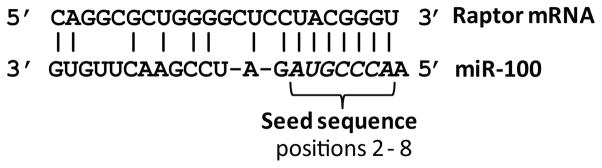

The major activity of miRNAs is translational suppression. While associated with the RISC, miRNAs can form duplexes with target mRNA sequences. Perfectly base-paired duplexes can form, but more commonly, miRNAs form imperfect hybrids with their targets (Figs. 2 and 3). Most miRNA-target interactions involve perfect or near-perfect sequence complementarity across miRNA positions 2 through 8, the seed sequence. The ability to form imperfect hybrids allows individual miRNA species to interact with multiple targets. This provides a wide range of biological control, even as it makes it difficult to reliably predict targets.

Fig. 3.

Predicted interaction between a miRNA (miR-100) and one of its predicted targets (Raptor mRNA). Possible Watson-Crick basepairing is indicated by vertical bars and the perfectly basepaired seed sequence at miRNA positions 2 through 8 is italicized.

While translational repression is the most common outcome of miRNA regulation, miRNAs can also act as positive regulators (Steitz and Vasudevan, 2009). One example of this is the cell cycle-dependent regulation of tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) by miR-369-3. Predicted binding sites for miR-369-3 are present in an AU-rich element in the TNFα - 3′UTR. In proliferating cells, the miR-393-3/RISC interaction leads to translational repression. Under conditions of serum starvation, the Ago2-RISC associates with the fragile-X-mental retardation related protein (FXR1), which leads to up-regulation of TNFα. AU-rich elements are present in the 3′ untranslated regions (3′ UTR) of other genes whose expression levels are regulated in a cell cycle-linked manner, thus related mechanisms likely regulate numerous other targets.

It is clear that miRNAs can have profound and subtle effects on gene regulation. Single miRNAs can serve as key regulators of important steps in organismal development, cellular differentiation, and oncogenesis. Individual miRNAs can target multiple mRNA species and can have multiple targets in individual mRNAs. Conversely, individual mRNAs can be targeted by multiple miRNAs. miRNA regulatory networks are interwoven with other forms of regulation. Thus, miRNAs can help to fine-tune expression levels, enable rapid changes in protein expression in response to environmental stimuli, and complement other forms of negative regulation to ensure that some particularly potent proteins are not inadvertently expressed at the wrong time or in the wrong place. As an example of this, herpesvirus-encoded miRNAs can contribute to regulation of the latent-to-lytic switch (described in Section 4.1).

3. Analysis of miRNAs

miRNAs have been identified by methods that include (i) bioinformatic predictions based on properties such as size, stability, and evolutionary conservation of predicted hairpin structures (Li et al., 2010), (ii) cloning and sequencing of small RNAs followed by bioinformatic analyses to see whether they may have originated from appropriate precursor hairpins, and (iii) increasingly, by deep sequencing of populations of small RNAs, followed by bioinformatic analysis of possible precursor structures (Creighton et al., 2009). Validation can include quantitative RT-PCR and Northern blotting to verify appropriate precursor and product sizes.

miRNA levels can be measured with varying levels of relative or absolute quantitative precision by methods that include miRNA gene arrays, bead-based assays, Northern blots, quantitative RT-PCR, and counting the frequency of detection in deep sequencing experiments. Deep sequencing is particularly attractive for miRNA analyses because the size of miRNAs is nicely compatible with the read lengths of many current generation high-throughput sequencers.

Identification and validation of miRNA targets remains a hard problem (Alexiou et al., 2009; Barbato et al., 2009). The challenge is rooted in the large number of potential targets made possible by the ability of miRNAs to interact with their targets via imperfect hybrids (Fig. 3). Numerous computational approaches have been developed to deal with the problem of target degeneracy, but positive predictive values for individual candidate targets remain low (Alexiou et al., 2009; Barbato et al., 2009; Li et al., 2010; Shomron et al., 2009). Investigators interested in the biological effects of particular miRNAs are commonly confronted with lists of hundreds of predicted targets for the miRNA of interest, with somewhat different lists and relative scores being generated by the various predictive algorithms. Individual candidate targets can be evaluated by linking their predicted miRNA binding site to a suitable reporter, and then measuring reporter activity in the presence of biochemical mimics of the miRNA of interest (Orom and Lund, 2010). Engineered mutations in the seed sequence of either the miRNA mimic or the target can help in assessing the specificity of the interaction.

Although the most common activity of miRNAs is translational suppression, miRNAs can reduce mRNA levels, for example by routing mRNAs for degradation in processing bodies (P bodies). In addition, miRNA regulation of regulatory proteins can influence transcript levels for other genes in regulatory pathways and networks. Thus, gene arrays can be used to identify targets of miRNAs and miRNA-regulated pathways (Orom and Lund, 2010). A useful screening approach for identifying effects at the protein level employs stable isotope labeling in cell culture (SILAC) (Baek et al., 2008; Selbach et al., 2008; Vinther et al., 2006). In one variation of this approach, cells are divided into two populations. An individual miRNA is over expressed in one population and one of the populations is grown in cell culture media that is enriched in amino acids that harbor stable heavy isotopes of carbon and nitrogen (13C and 15N). Mass spectroscopy can then be used to identify relative differences in expression of individual proteins, as expressed in the presence of absence of the miRNA of interest. Another relatively unbiased screening strategy involves immunoprecipitation of RISC complexes with antibodies against RISC components or by pull-down of the RISC via biotinylated synthetic miRNAs, followed by gene array analysis (Grey et al., 2010).

A final step in target validation is to verify that interactions observed in isolation are biologically meaningful (Orom and Lund, 2010). Thus, it is important to verify that the biological process or pathway associated with the putative target is in fact regulated by the miRNA of interest. Such experiments can be very challenging given the plethora of possible targets for most miRNAs.

4. Viruses and miRNAs

4.1. Virally encoded miRNAs

miRNAs are encoded by several types of viruses that have dsDNA genomes, including adenoviruses, an ascovirus, herpesviruses, and polyomaviruses (Skalsky and Cullen, 2010). Thus far, virally encoded miRNAs have not been found for papillomaviruses or poxviruses. No RNA virus miRNAs have been detected. The HIV-1 TAR RNA forms a structure that can be cleaved to form miRNA precursors, but mature TAR-derived miRNAs have not been detected.

Viruses of the family Herpesviridae are distributed among three subfamilies, the Alpha-, Beta-, and Gammaherpesvirinae, with viruses within a subfamily sharing major biological properties, as well as features of their genome structure and genetic content (Pellett and Roizman, 2007). Herpesviruses are remarkable in the numbers of miRNAs they encode, and for the diversity of miRNA coding strategies represented across the family (reviewed in (Boss et al., 2009; Skalsky and Cullen, 2010; Umbach and Cullen, 2009)). Herpesvirus miRNAs are encoded singly, as clusters, and in sense or antisense orientations relative to overlapping viral genes. Herpes simplex viruses 1 and 2 (HSV-1 and HSV-2; Human herpesvirus 1 and Human herpesvirus 2) encode at least 8 and 6 miRNAs, respectively, most of which map to the latency associated transcript (LAT) and are antisense to ICP0, a key transcriptional regulator, and ICP34.5, a late gene that is required for viral gene expression in neurons (Boss et al., 2009; Skalsky and Cullen, 2010). HCMV, a betaherpesvirus, encodes at least 14 miRNAs (Dolken et al., 2009) (details in Section 5.2). The other human betaherpesviruses, Human herpesvirus 6 and Human herpesvirus 7, are not predicted to encode miRNAs (Pfeffer et al., 2005). For the gammaherpesviruses, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV; Human herpesvirus 4) encodes at least 25 miRNAs, and the major latency-associated region of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV; Human herpesvirus 8) encodes 12 miRNA genes, which produce at least 17 miRNAs (Boss et al., 2009; Cai et al., 2005; Grundhoff et al., 2006; Pfeffer et al., 2005; Samols et al., 2005). Ten of the KSHV miRNA genes are clustered in an intron that maps between ORF71 and the kaposin open reading frame. Murine gammaherpesvirus 68 (Murid herpesvirus 4) encodes miRNAs that are physically linked to virally-encoded, RNA polymerase III-transcribed tRNAs (Pfeffer et al., 2005), with the pre-miRNA being liberated from the tRNA by cleavage with the cellular tRNAse Z (Bogerd et al., 2010).

Although still a new area of research, activities and biological roles have been identified for several herpesvirus-encoded miRNAs. Some virally-encoded miRNAs are encoded antisense to known protein coding regions, and target transcripts for those proteins. In such cases, the miRNA:mRNA hybrid has perfect complementarity and would be targeted by an Ago2/RISC for cleavage. Thus, a long observed small transcript from the EBV DNA polymerase gene (BALF5) turned out to be a product of cleavage mediated by EBV miRNA that is encoded on the complementary strand (Barth et al., 2008; Furnari et al., 1993; Pfeffer et al., 2004). Some viral miRNAs have no known viral target, but target cellular transcripts. Examples include targeting of the p53 up-regulated modulator of apoptosis (PUMA) by EBV miR-BART5 (Choy et al., 2008), and thrombospondin 1 by four KSHV miRNAs (miR-K12-1, miR-K12-3-3p, miR-K12-6-3p, and miR-K12-11) (Samols et al., 2007).

Virally-encoded miRNAs can have roles during latent and lytic infections. During latency, some viral miRNAs contribute to maintaining IE genes in an inactive state (Grey et al., 2007; Murphy et al., 2008) (Bellare and Ganem, 2009; Cai et al., 2005; Tang et al., 2009; Umbach et al., 2008). Latency-associated miRNAs of KSHV can target cellular genes, including an inhibitor of angiogenesis (thrombospondin 1) and a proapoptotic gene, Bcl-2-associated factor that can influence reactivation from latency (Ziegelbauer et al., 2009).

4.2. Viruses and host miRNAs

Virus infections can be expected to result in changes in cellular miRNA expression, biogenesis, or activity that are (i) cellular responses to the infection, and/or (ii) changes induced by the virus that benefit the virus. One of the first surveys of the effect of virus infection on host cell miRNAs was done for human immunodeficiency virus 1 (HIV-1) (Triboulet et al., 2007). Among other changes, miRNAs expressed from the mir-17/92 cluster were markedly downregulated. Transfections of mimics of some of these miRNAs resulted in reduced HIV-1 replication, while transfection of complements of these miRNAs (anti-miRNAs, or antigomirs) resulted in enhanced replication. Thus, it appears that miRNAs expressed from the miR-17/92 cluster have antiviral activity that the virus must suppress to ensure efficient replication. In other work, herpes simplex virus 1 infection of human neural cells led to increased expression of miR-146a, which is transcriptionally regulated by NF-κB in response to inflammatory cytokines (Hill et al., 2009). Santhakumar et al. (Santhakumar et al., 2010) devised an elegant screen for miRNA activity during virus infection. The screen is based on measuring the effect of miRNA inhibitors and mimics on expression of GFP from viral genomes. A set of cellular miRNAs was identified that can inhibit infection by members of all three herpesvirus families (herpes simplex virus 1, murine cytomegalovirus, and murine gamma herpesvirus 68), as well as an RNA virus (Semliki Forest virus). These miRNAs affected the expression of mRNAs of genes involved in biological pathways important during infection, including the ERK/MAP and PI3K/AKT pathways, prostaglandin synthesis, and oxidative stress signaling.

5. HCMV encoded miRNAs

5.1. HCMV genomes and gene expression

As isolated from humans, HCMV genomes are approximately 235 kb in length and harbor approximately 165 protein-coding genes (Dolan et al., 2004; Murphy et al., 2003) (Fig. 4). Mutations in the RL13 and then the UL128 locus occur relatively soon during passage in fibroblasts, with assorted other changes accumulating during more extensive passage (Dargan et al., 2010). In some virus strains that have been highly passaged in cell culture, specifically, the widely used Towne and AD169 strains, the genome has rearranged by deleting segments of 13 kb (Towne strain) and 15 kb (strain AD169) that encode at least 19 proteins, while duplicating another segment (Cha et al., 1996).

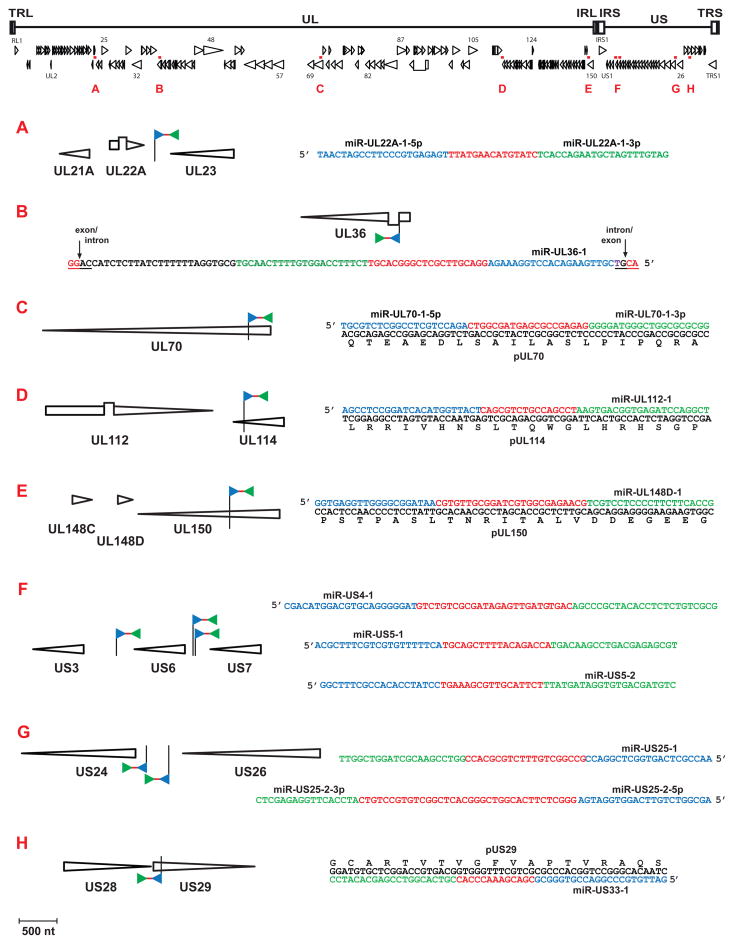

Fig. 4.

Genomic locations and environments of HCMV-encoded miRNAs. HCMV genomic architecture and open reading frames representative of clinical strains are illustrated across the top of the diagram (Davison et al., 2003). Loci encoding miRNAs are indicated with small red boxes and by letters. Each of the lettered regions is expanded below (all at the same scale). In the expanded diagrams, locations of miRNA hairpins are indicated by pennants that consist of a staff that marks the location of the 5′ end of the stem-loop structure, a blue triangle representing the 5′ stem, a red line representing the loop, and a green triangle representing the 3′ stem. Other than the location of the staff, the pennants are not drawn to scale; at scale, the stem-loop structures would be shorter than the blue triangles. For miRNAs that do not span protein coding regions, only the sequence of the stem-loop region is shown (5′ stem in blue, loop in red, and 3′ stem in green; sequence segments at the 5′ and 3′ ends of the stem-loop sequences that may extend beyond the known miRNA sequences are not shown). For miRNAs that span protein coding regions, the protein coding sequence and the protein sequence are also shown. Stem-loop arms that are processed to mature miRNAs are indicated with the miRNA name. miR-UL31-1 (locus B) may be expressed as a miRtron, so the intron/exon boundaries are shown. All sequences are from HCMV strain AD169 (Accession number NC_001347), except for miR-148D-1, which is from the HCMV strain Merlin sequence (Accession number NC_006273).

HCMV proteins are encoded on both genomic strands, with little overlap of protein coding open reading frames. HCMV genes fall into two major classes: those expressed during the lytic phase and those expressed during latency. To a first approximation, lytic genes belong to one of three major kinetic classes: alpha, or immediate early genes can be transcribed in the absence of de novo protein synthesis. Thus, alpha genes are generally transcribed during the earliest stages of lytic infection, and can be transcribed in the presence of protein synthesis inhibitors such as cycloheximide. Beta, or early genes are dependent on immediate early proteins for their transcription, and generally code for proteins involved in viral DNA replication. Transcription of gamma, or late genes, is dependent on viral DNA replication, and thus commences later during lytic replication. Most viral structural proteins are products of gamma genes. Only a few HCMV mRNAs are spliced. In addition to protein-coding mRNAs, HCMV expresses a large number of transcripts that do not appear to encode proteins; many of these transcripts are antisense to mRNAs and have no known function (Zhang et al., 2007). HCMV encodes proteins (TRS1 and IRS1) that bind dsRNA and inhibit protein kinase R (PKR) mediated shutoff of protein synthesis (Hakki and Geballe, 2005). Sense-antisense transcript pairs would be expected to be processed to virus-specific small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) that would have the potential to affect HCMV gene regulation via RNAi, but this has not been demonstrated.

Functionally, HCMV genes can be grouped into two major classes: those directly responsible for virus structure and replication (core genes), and those responsible for modulating the interaction between the virus and the host cell and organism (accessory genes) (Davison et al., 2002). Most core genes are conserved across the herpesvirus family. Accessory genes are much more divergent, a reflection of the diversity of these viruses with respect to host cell and tissue tropism, routes of infection, mechanisms of immune evasion, and form of latency. Most core genes are essential for virus replication in cell culture, while many accessory genes are not always required for replication.

HCMV exerts profound and diverse influence on cellular processes. These range from biasing the outputs of metabolic pathways in ways that are to the advantage of the virus (Chambers et al., 2010; Munger et al., 2008), remodeling of the cytoplasmic secretory apparatus (Das et al., 2007), reprogramming the cell cycle and apoptosis pathways (Sanchez and Spector, 2008), and employing a variety of methods to avoid detection and destruction by the host immune system (Mocarski, Jr., 2004).

5.2. Identification and mapping of HCMV-encoded miRNAs

Clinical isolates of HCMV encode at least 14 miRNAs (Dunn et al., 2005; Grey et al., 2005; Pfeffer et al., 2005) (Fig. 4), which were initially identified by (i) Northern blot confirmation of predictions made on the basis of stem loop structures that are conserved between HCMV and its close relative, chimpanzee CMV (CCMV) (Grey et al., 2005; Grey and Nelson, 2008), (ii) bioinformatic prediction that HCMV was likely to encode miRNAs followed by cloning and then sequencing a library of small RNA species present in HCMV-infected cells (Pfeffer et al., 2005), and (iii) through a combination of small RNA cloning, sequence analysis, and then Northern blotting (Dunn et al., 2005). Thus far, deep sequencing has not been applied to the search for HCMV-encoded miRNAs, thus the list of HCMV miRNAs might expand.

The 14 Northern blot-confirmed HCMV-encoded mature miRNAs arise from 11 pre-miRNAs (Table 1 and Fig. 4). They are named according to the overlapping gene or the nearest upstream gene encoded on the same strand of the viral genome. HCMV miRNAs genes are scattered across the genome (Fig. 3); this contrasts with miRNAs of alphaherpesviruses and gammaherpesviruses, for which most miRNAs are encoded as clusters (Boss et al., 2009; Dolken et al., 2009). HCMV miRNAs are well-conserved among HCMV strains (Dunn et al., 2005), and all 11 HCMV miRNAs that were assayed by quantitative RT-PCR were expressed in cells infected with two low-passage clinical HCMV strains (Stern-Ginossar et al., 2009). miR-UL22A-1-5p, miR-UL22A-1-3p, and miR-US25-1 were detected by Northern blots in four cell types relevant to HCMV infection, primary fibroblasts, endothelial cells, epithelial cells, and astrocytes (Dunn et al., 2005). Five of the 14 HCMV miRNAs map within and antisense to protein-coding open reading frames (ORF), while the remainder do not map within known protein coding sequences; miR-36-1 is located in an intron.

Table 1.

HCMV miRNAs

| miRa | Genomic environment | Verified Target(s) | Kinetic Classb | Function | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-UL22A-1-5p miR-UL22A-1 miR-UL22A-5p miR-UL22-1 miR-UL-22A miR-UL23-5p |

Intergenic region between UL22A and UL23 | E 2 hpi | (Dunn et al., 2005; Grey et al., 2005; Stern-Ginossar et al., 2009) | ||

| miR-UL22A-1-3p miR-UL23-3p |

Intergenic region between UL22A and UL23 | IE 24 hpi | (Dunn et al., 2005) | ||

| miR-UL36-1 miR-UL-36 |

Spliced intron of UL36 | IE 24 hpi | (Grey et al., 2005; Stern-Ginossar et al., 2009) | ||

| miR-UL70-1-5p miR-UL-70 miR-UL-70-1 |

Within and antisense to UL70 coding region | IE 24 hpi | (Grey et al., 2005; Stern-Ginossar et al., 2009) | ||

| miR-UL70-1-3p | Within and antisense to UL70 coding region | (Grey et al., 2005; Stern- Ginossar et al., 2009) | |||

| miR-UL112-1 miR-UL-112 |

Within and antisense to UL114 coding region | Cellular: MICB Viral: IE1 |

E 24 hpi | Inhibits IE1 expression, acts as immune response inhibitor and helps viral replication. | (Grey et al., 2005; Murphy et al., 2008; Stern-Ginossar et al., 2007; Stern-Ginossar et al., 2009) |

| miR-UL148D-1 miR-UL-148D |

Within and antisense to UL150 coding region, | Not required for virus replication in cell culture. | (Dunn et al., 2003b; Grey et al., 2005; Stern-Ginossar et al., 2009) | ||

| miR-US4-1 miR-US-4 |

Intergenic region between US3 and US6 | E 24 hpi | Not required for virus replication in cell culture. | (Dunn et al., 2003b; Grey et al., 2005; Stern-Ginossar et al., 2009) | |

| miR-US5-1 | Intergenic region between US6 and US7 | E 24 hpi | Not required for virus replication in cell culture. | (Dunn et al., 2003b; Grey et al., 2005; Stern-Ginossar et al., 2009) | |

| miR-US5-2 | Intergenic region between US6 and US7 | E, 24 hpi | Not required for virus replication in cell culture. | (Dunn et al., 2003b; Grey et al., 2005; Stern-Ginossar et al., 2009) | |

| miR-US25-1 miR-UL24 |

Intergenic region between US24 and US26 | Cellular: Cyclin E2 | E 8 hpi | Reduces DNA synthesis and viral replication. Inhibits cyclin E2 protein expression. | (Fannin Rider et al., 2008; Grey et al., 2010; Grey et al., 2005; Stern-Ginossar et al., 2009) |

| miR-US25-2-5p | Intergenic region between US24 and US26 | E 48 hpi | Not required for virus replication in cell culture. | (Dunn et al., 2003b; Grey et al., 2005; Stern-Ginossar et al., 2009) | |

| miR-US25-2-3p | Intergenic region between US24 and US26 | Not required for virus replication in cell culture. | (Dunn et al., 2003b; Grey et al., 2005; Stern-Ginossar et al., 2009) | ||

| miR-US33-1 miR-US-33 |

Within and antisense to US29 coding region | Not required for virus replication in cell culture. | (Grey et al., 2005; Stern- Ginossar et al., 2009) |

miRNAs are named according to a recent compilation (Dolken et al., 2009); these names are used in the text. Previous designations are listed beneath the current designation. Fields for which information is not available were left blank.

In addition to the kinetic class, the time of earliest detection in Northern blot time-course experiments is also shown. IE, immediate early; E, early.

5.3. miRNA orthologs in HCMV, MCMV, and chimpanzee cytomegalovirus (CCMV)

Although miRNAs are expressed by many herpesviruses, including viruses from each of the subfamilies, no miRNA is conserved across the family. Other than for very closely related viruses, e.g., HCMV and CCMV (Panine herpesvirus 2) or the herpes simplex viruses and simian B virus (Macacine herpesvirus 1), there is little conservation of individual miRNAs even within subfamilies (Dolken et al., 2007; Dolken et al., 2009; Skalsky and Cullen, 2010). CCMV is the closest known relative of HCMV (Davison et al., 2003); on the basis of sequence comparisons, 10 of the 11 pre-miRNAs of HCMV are conserved in CCMV, but there is no experimental data yet to demonstrate that the CCMV miRNAs are indeed expressed (Dolken et al., 2009).

The more distantly related murine cytomegalovirus (MCMV; Murid herpesvirus 1) encodes 18 pre-miRNAs that produce 21 mature miRNAs during lytic infection (Dolken et al., 2007). Eleven of the 18 pre-miRNAs are distributed among 3 clusters: m01, m21/m22/M23, and m107/m108 (Buck et al., 2007). There is no discernable conservation with respect to overall sequence, seed sequences, or genomic location between the MCMV and HCMV miRNAs (Buck et al., 2007). Although HCMV and MCMV do not encode orthologous miRNAs, the ability to genetically manipulate MCMV and to use it in laboratory infections of its native host provides a useful animal model for learning how miRNAs can function during virus infections in vivo (Buck et al., 2007; Dolken et al., 2007).

5.4. Kinetics of HCMV miRNA expression

During lytic infection in cultured cells, HCMV miRNAs are expressed at high levels, constituting as much as 20% of the total miRNA population in infected cells (Dunn et al., 2005). Two main types of kinetic studies have been done: time course experiments in which the steady-state levels of individual miRNA species are detected by Northern blotting, and experiments in which the state of the cell is altered using drugs. In such experiments, infections are performed in the presence of a protein synthesis inhibitor (cycloheximide) to identify alpha genes or a DNA synthesis inhibitor such as foscarnet or phosphonoacetic acid to identify and differentiate beta and gamma genes.

In time course experiments, some miRNAs were detected by Northern blots as early as 2 hpi or 8 hpi, while others were not detected until 24 hpi, with steady-state levels remaining relatively constant over the remaining time (48 or 72 hrs total) (Table 1). All of the HCMV miRNAs studied thus far are expressed either as IE or E genes; none are expressed as L genes (Table 1).

miR-UL36-1 is expressed with unusual kinetics. An apparent pre-miRNA species of ~90 nt is detectable as early as 8 hpi and in the presence of cycloheximide, but the mature miRNA is not detectable until 24 hpi, and was not detected in the presence of cycloheximide (Grey et al., 2005). miR-UL22A-1-5p was not detected in the presence of cycloheximide (Grey et al., 2005) but a miRNA apparently derived from the same pre-miRNA (miR-UL22A-1-3p) was detected in the presence of cycloheximide (Dunn et al., 2005). These results suggest that HCMV infection alters some aspects of miRNA biogenesis.

6. Targets and biological activity of HCMV miRNAs

Like host miRNAs, virus encoded miRNAs have the potential to target both viral and host mRNAs. Only a few targets have been identified for HCMV-encoded miRNAs, thus their functions are still largely unknown. As described above, miRNA targets can be identified via two main approaches: bioinformatic target prediction followed by experimental verification, and through the use of relatively unbiased biochemical screens.

6.1. Viral targets of HCMV encoded miRNAs

Grey et al. used a target prediction algorithm (RNAhybrid) to identify candidate targets of miR-UL112-1 (Grey et al., 2007) in 3′UTRs of HCMV genes. Fourteen candidate targets identified as being conserved between HCMV and CCMV were then evaluated in a luciferase reporter assay. Co-transfection assays were performed using expression plasmids harboring the candidate HCMV 3′UTR target sequence, and a plasmid expressing either miR-UL112-1 or a random hairpin sequence negative control. miR-UL112-1 reduced expression from constructs that harbored the 3′UTR from UL112/113, UL120/121, and UL123 (IE72 or IE1, an important HCMV gene regulator). In further studies they found that miR-112-1 downregulated IE1 protein expression but not its mRNA. As expressed from a plasmid containing the pre-miR-112-1 sequence, miR-112-1 led to reduced IE protein expression and reduced viral DNA levels at 24 hpi. This demonstrated that a single viral miRNA can regulate the expression of multiple viral genes.

Murphy et al. devised an algorithm for predicting viral genes targeted by viral miRNAs (Murphy et al., 2008). They found strongly predicted interactions between several HCMV miRNAs and 3′ UTRs of protein coding open reading frames, including a predicted interaction between miR-112-1 and the UL123 (IE1) 3′ UTR. In addition to demonstrating that miR-112-1 could suppress expression of a reporter construct containing its predicted target, two mutant viruses were constructed, one of which lacked the miRNA target seed sequence and the other was unable to express the miRNA. These viruses and a revertant had growth properties similar to the parental virus in cultured fibroblasts, although the mutants expressed increased levels of IE1 protein at the latest time point tested (48 hpi), consistent with the hypothesis that miRNA suppression of IE and other lytic genes can contribute to establishment and maintenance of latency.

Stern-Ginossar et al. found that miR-UL112-1, whose gene is located within and antisense to the UL114 open reading frame (Fig. 4, Table 1) targets and reduces expression of pUL114, which encodes a uracil DNA glycosylase that can affect minimal viral replication (Stern-Ginossar et al., 2009). The authors suggest that miR-UL112-1 may function either to increase the mutation rate late in infection or to suppress lytic infection as part of establishing latency.

6.2. Cellular targets of HCMV encoded miRNAs

Target prediction software (RepTar) was used to identify human genes whose 3′UTRs might be targeted by HCMV encoded miRNAs (Stern-Ginossar et al., 2007). The highest score was for a possible interaction between HCMV miR-112-1 and the gene encoding the major histocompatibility complex class-1-related chain B (MICB). MICB interacts with the natural killer (NK) cell activating receptor, NKG2D, which can lead to NK killing of infected cells in which MHC antigen presentation has been inhibited as part of the viral immune evasion strategy. As part of counteracting this, HCMV pUL16 downregulates cell-surface expression of MICB (Cosman et al., 2001; Dunn et al., 2003a). It was hypothesized that miR-UL112-1 may contribute to ensuring that MICB expression is downregulated, thus helping the virus to avoid this arm of the innate immune response. After verification by a reporter assay, subsequent experiments showed that HCMV miR-UL112-1 can indeed downregulate MICB gene expression, which led to decreased binding of NKG2D and reduced NK cells killing. Subsequent studies showed that (i) KSHV and EBV also encode miRNAs that target MICB, (ii) the MICB-targeting viral miRNAs are not homologous to each other, (iii) the viral miRNAs interact with sequences in the MICB 3′UTR that overlap with but are distinct from cellular miRNA binding sites, and (iv) the viral and cellular miRNAs can have additive and even synergistic effects on MICB expression (Nachmani et al., 2009; Nachmani et al., 2010).

Lentivirus vectored GFP constructs were used to analyze 11 of the HCMV encoded miRNAs for their ability to reduce cell-surface expression of several immune system related genes (MHC class I, MICA, ULBP2, ULBP3, ICAM1, IFN-α receptor, and PVR), some of which harbor seed sequence matches with some of the HCMV miRNAs (Stern-Ginossar et al., 2009). Somewhat surprisingly, none of the tested genes was affected by any of the viral miRNAs. In tests of a panel of 10 of these HCMV miRNAs, miR-US25-1 and US25-2 inhibited HCMV DNA replication, reduced expression of an IE and a late gene, and reduced infectious yields. The likelihood that these viral miRNAs target a cellular gene(s) is suggested by the observation that they could also inhibit the replication of other DNA viruses (herpes simplex virus 1 and an adenovirus), but not an RNA virus (influenza A) (Stern-Ginossar et al., 2009).

Based on their previous work showing that miR-US25-1 is one of the most highly expressed HCMV miRNAs (Grey et al., 2005), Grey et al. performed two RISC-immunoprecipitation screens to identify cellular targets of miR-US25-1 (Grey et al., 2010), which fell into three main groups: cell cycle control, tumor progression, and histone genes. The major effect of miR-US25-1 was a reduction in levels of target transcripts and proteins. A novel observation was that most of the targets for miR-US25-1 are in 5′UTR regions rather than in coding or 3′UTR regions. A recombinant virus deleted for the miR-US25-1 pre-miR coding region showed modest differences in regulation of its targets during infection, but the mutant virus replicated with efficiency equivalent to its parent.

7. HCMV and host miRNAs

7.1. Cellular miRNA expression after HCMV infection

As described above, HCMV employs diverse mechanisms for the regulation of cellular system, and the infection results in a variety of changes in host cell signaling pathways, including calcium flux and lipid metabolism, activation of kinase signaling cascades, cytoskeleton re-arrangements, and activation of cellular transcription factors.

Wang et al. hypothesized that HCMV infection can alter cellular miRNA expression and that re-regulated miRNAs may play roles in HCMV infection (Wang et al., 2008). Using miRNA microarrays, the time course of cellular miRNA expression was monitored in HCMV infected cells. Total RNA was extracted at different time points (6, 24, 48, and 96, or 120 h post infection) from MRC-5 cells that had been infected with HCMV Towne BAC at a MOI of 2. Forty nine miRNAs had significant changes in their expression levels at at least one time point. There were no global unidirectional changes; rather, some miRNAs were either positively or negatively regulated, with changes for these miRNAs sometimes being transient (only seen at one time point) and sometimes the direction of change persisted over the full time course. In addition, the patterns of changes in miRNA levels linked to the time course of infection. Thus, the patterns seen at 6 hpi were most similar to patterns in uninfected cells, and the late time points were most similar to each other.

The diversity of responses for individual miRNAs demonstrated that HCMV infection does not affect all aspects of miRNA expression and biogenesis in the same manner. Instead, management of miRNA expression is regulated in a much more fine-grained manner. This is consistent with the observations described above for HCMV-encoded miRNAs, such as the expression of the miR-UL36-1 pre-miRNA in the presence of cycloheximide but not the mature form. The coherence of the temporal changes in expression patterns suggests that there are some shared modes of regulation.

This initial study of the effects of HCMV infection on cellular miRNA expression left many unanswered questions. These include (i) the relationship of changes in cellular miRNA expression to expression of the various kinetic classes of viral genes, (ii) the identity of the viral genes that are the effectors of re-regulation, and (iii) the nature of cellular miRNA expression in other cell types and during infections with low passage clinical isolates. In addition, the array used did not contain probes for all currently known miRNAs.

The miR-199a/214 cluster (miR-199a-5p, miR-199a-3p, and miR-214) was recently found to be downregulated in HCMV- and MCMV-infected cells (Santhakumar et al., 2010). Gene array analyses were conducted on cells transfected with a miR-199a-3p mimic and inhibitor. Affected transcripts were associated with cellular pathways related to PI3K/Akt signaling, ERK/MAPK signaling, prostaglandin synthesis, oxidative stress signaling, and pathways involved in endocytic viral entry; all of these pathways are important during HCMV infection.

7.2. Roles of cellular miRNAs in HCMV biology

Cellular miRNAs re-regulated during the course of HCMV infection have predicted and demonstrated targets on biological pathways that are important in cell proliferation, differentiation, or oncogenesis. After consideration of lists of predicted targets for the cellular miRNAs that had the most significant changes in expression after HCMV infection, Wang et al. elected to conduct further studies on miR-100 and miR-101, two of the most strongly downregulated miRNAs (Wang et al., 2008). These miRNAs were chosen for further study in part because they both had predicted targets on the phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase-Akt-mammalian target of rapamycin (PI3K/Akt/mTOR) pathway. It is well known that many mammalian viruses regulate diverse signaling pathways (Chaisuparat et al., 2008; Cooray, 2004; Mannova and Beretta, 2005; Zaborowska and Walsh, 2009). Most mammalian DNA viruses inhibit the effects of stress signals and regulate the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway to enhance their replication and survival through maintenance of growth, metabolic, anti-apoptotic, and translational functions (Alwine, 2008; Buchkovich et al., 2008; Hay and Sonenberg, 2004; Mamane et al., 2006).

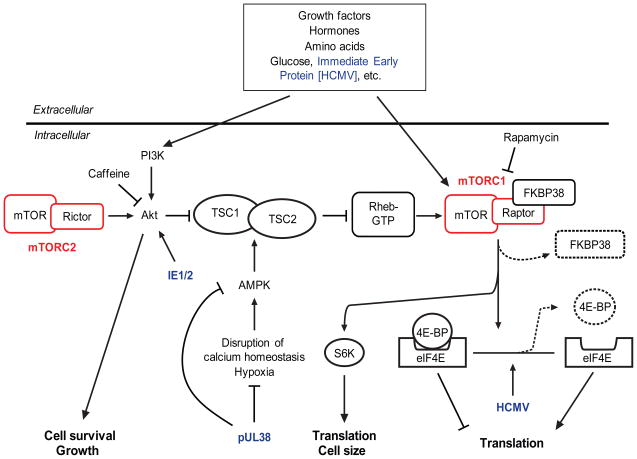

Several mechanisms have been identified by which HCMV directly regulates the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway (Alwine, 2008; Buchkovich et al., 2008) (Fig. 4): (i) HCMV IE1 and IE2 can activate Akt phosphorylation and also stimulate PI3K (Yu and Alwine, 2002). (ii) pUL38 (an HCMV immediate early protein) limits 5′ adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase (AMPK) phosphorylation and inactivates tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC), thereby inhibiting stress signals triggered by HCMV infection, as well as by hypoxia or disruption of calcium homeostasis (Moorman et al., 2008). (iii) HCMV also acts downstream of mTORC1, causing either hyperphosphorylation of 4E-BP to lower its affinity for elF4E, or increasing levels of elF4E to titrate out hypophosphorylated 4E-BP; in either case, translation initiation is maintained (Walsh et al., 2005).

Wang et al. found that miR-100 and -101 each has predicted targets in the 3′-UTR of the mTOR mRNA. In addition, miR-100 has a predicted target in the 3′-UTR of raptor, a partner of mTOR in the rapamycin sensitive mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1), and miR-101 has two predicted targets in the 3′-UTR of rictor, a partner of mTOR in the rapamycin insensitive mTOR complex 2 (mTORC2). To determine whether miR-100 and -101 interact with components of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway, reporter plasmids were constructed in which the 3′-UTRs of mTOR and raptor were inserted into the 3′-UTR of an EGFP expression plasmid (pHygEGFP-mTOR and pHygEGFP-raptor). MRC-5 cells were co-transfected with the reporter plasmids (pHygEGFP-mTOR and pHygEGFP-raptor) and synthetic mimics of miR-100 and/or -101. EGFP expression from pHygEGFP -mTOR, which has predicted targets for miR-100 and -101, was reduced by 48% by the combination of the miR-100 and -101 mimics. In cells transfected with pHygEGFP-raptor, which has a predicted target for miR-100, the miR-100 mimic reduced EGFP expression by 50% and the miR-101 mimic had no effect alone. The miR-100 and -101 mimics also suppressed expression of endogenous levels mTOR in transfected Hela cells.

In follow-up experiments, we have found that these miRNAs can also affect expression of endogenous rictor and raptor proteins; the effects are different in uninfected vs. infected cells (K.D. and P.E.P., unpublished data). Additional computational analysis revealed that some HCMV-regulated cellular miRNAs have predicted targets on positive (PI3K, AKT-IP, mTOR, raptor, rictor, and SINI) and negative (TSC1 and 2, FKBP38, and 4E-BP) regulators of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway (K.D. and P.E.P., unpublished observations). As described in Sections 4.2 and 7.1, the miR-199a/214 cluster (miR-199a-5p, miR-199a-3p, and miR-214) is downregulated in HCMV- and MCMV-infected cells and these miRNAs are negative regulators of MCMV replication (Santhakumar et al., 2010). These miRNAs downregulate components of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway, as well as other pathways relevant to HCMV biology.

Several recent reports confirm the observation that miR-100 and -101 can regulate components of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway and extend this to other regulatory pathways and possible roles in different type of cancers. miR-100 expression is strongly downregulated in clear cell ovarian cancer and can regulate mTOR expression (Nagaraja et al., 2010). miR-100 is also downregulated in adrenocortical tumors, which have elevated levels of mTOR, p-mTOR, raptor and insulin-like growth factor (IGF-IR) (Doghman et al., 2010). A miR-100 inhibitor increased expression of mTOR, raptor, and IGF-IR in adrenocortical cell tumor cell lines. miR-100 activity was dependent on its predicted binding sites in the 3′UTR of the mRNAs for these proteins. miR-101 (i) is downregulated in colorectal cancer and can reduce COX-2 mRNA levels (Strillacci et al., 2009); (ii) inhibits expression and function of Enhancer of Zeste Homolog 2 (EZH2) in cancer cell lines (Cao et al., 2010; Varambally et al., 2008), (iii) inhibits cell invasion and migration of prostate cancer cell lines (Cao et al., 2010), and negatively regulates the amyloid precursor protein (APP), which affects the accumulation of the amyloid beta (Aβ) proteolytic products that are associated with Alzheimer disease (Vilardo et al., 2010). It is no surprise that at least some of the miRNAs affected by HCMV infection are indeed involved regulation of important cellular pathways.

To assess whether downregulation of miR-100 and -101 might influence viral replication, these miRNAs were added back in the form of synthetic miRNA mimics, thus reversing the downregulation (Wang et al., 2008). In this experiment, MRC-5 cells were transfected with various concentrations of synthetic mimics of miR-100 and -101 and then infected with HCMV; culture supernatants were harvested at 4 days after infection. In a concentration-dependent manner, the synthetic miRNAs reduced virus yield. Interestingly, when present at equal concentrations, the two mimics inhibited viral replication more effectively than did the same total concentration of either miRNA by itself. Although the details differ, this result is analogous to the HIV-induced suppression of a cellular miRNA that regulates an antiviral pathway (Triboulet et al., 2007).

miR-132 is among the miRNAs whose expression is elevated at 24 hpi (Wang et al., 2008). As originally observed for KSHV and then extended to HCMV (Lagos et al., 2010), upregulation of miR-132 after infection negatively regulates interferon expression and expression of interferon-stimulated genes, facilitating infection. It will be important to learn the mechanism(s) by which cellular miRNA expression is affected by HCMV infection, as well as the specific mechanism(s) by which expression of some cellular miRNAs can adversely impact viral replication. In addition, the roles of other miRNAs whose expression is altered by HCMV infection remain to be studied.

8. The miRNA-HCMV interface: clinical applications

A large percentage of the US population acquires HCMV at an early age (Staras et al., 2006). The virus establishes life-long latency and remains dormant after the primary infection, rarely causing any symptoms in healthy adults and children. Primary infection during pregnancy may lead to congenital infection in the newborn with serious consequences (Cannon and Davis, 2005). In adults, the virus can reactivate in immunocompromised patients with conditions such as HIV/AIDS or post-transplant immunosuppression, and then cause multi-organ disease including fever, pancytopenia, pneumonia, gastroenteritis, retinitis, and encephalitis (Mocarski et al., 2007).

8.1. Possible relevance of miRNAs to improving HCMV diagnosis

Molecular techniques such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR), as well as non-molecular techniques such as antigenemia are available for detection of HCMV virus. HCMV virus can be detected in blood, body fluids such as cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), broncho-alveolar lavage fluid (BAL) and urine, as well as in tissues (Kearns et al., 2001). Antigenemia assays detect the HCMV lower matrix protein pp65 expressed in leukocytes by immune-florescence staining. The number of HCMV antigen positive cells reflects the viral load. PCR-based methods are plasma based and measure the number of copies of virus present per milliliter of tested sample (Boeckh and Boivin, 1998). Although widely used in diagnosis of HCMV infection, both the tests have disadvantages. The antigenemia test is very labor intensive and has low sensitivity for detection in post-transplant patients before engraftment due to lack of leukocytes. The PCR method lacks standardization of the assays and an accepted universal CMV DNA standard. Importantly, these diagnostic tests do not reliably differentiate pathogenic and benign viral replication.

Methods such as microarray profiling and quantitative real-time reverse-transcriptase PCR (RT-PCR) are available for detection and quantification of miRNAs (Hunt et al., 2009). miRNAs can be reliably detected from various samples such as serum, cells and tissue sections due to their small size, relative stability and resistance to RNase degradation. Currently available quantitative RT-PCR methods to detect miRNAs are very sensitive and can be used on very small samples and even single cells (Paranjape et al., 2009). As shown by Wang et al. (Wang et al., 2008), the patterns of host cell miRNA expression change after HCMV infection. A unique miRNA expression pattern (profile) in response to infection may provide useful diagnostic and prognostic information. Signature profiles of cellular miRNAs have been identified for various diseases, including cancers, multiple sclerosis, stroke and asthma (Bartels and Tsongalis, 2009; Keller et al., 2009; Liu et al., 2009; Williams et al., 2009). miRNAs have also been identified in serum and plasma and may serve as biomarkers for some disease states such as prostate cancer, sepsis and acute myocardial infarction (D’Alessandra et al., 2010; Mitchell et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2010).

Expression patterns of cellular miRNAs in plasma, peripheral blood mononuclear cells that serve as a latent reservoir for the virus or from infected tissues such as lungs, liver, colon, during viral activity may illuminate useful early biomarkers for the diagnosis of HCMV infection. Changes in cellular miRNA expression profiles, possibly even prior to viral replication may provide solutions to current diagnostic challenges in HCMV infection.

8.2. miRNAs and management of HCMV infection

Current strategies to control HCMV infection in post-transplant population include either prophylaxis with antivirals or preemptive antiviral therapy based on weekly measurements of HCMV blood levels by PCR or antigen detection tests (Boeckh and Ljungman, 2009). Both strategies involve excessive antiviral drug use, with the attendant toxicities, frequent blood tests, need for intravenous access, and development of antiviral drug resistance. Given the high morbidity and mortality associated with HCMV infections and the difficulties in managing it, novel approaches are needed.

miRNA based therapeutics such as knockdown of target miRNAs by anti-miRNA oligonucleotides, or overexpression of miRNA by transfection or transduction are promising approaches for treating human diseases (Liu et al., 2008). miR-122 is a liver-specific miRNA which promotes hepatitis C replication; miR-122 antagonists have in vivo activity against HCV in non-human primates (Jopling et al., 2005; Lanford et al., 2010). Viral-encoded miRNAs that may have pathogenic properties offer a novel attractive target for antiviral therapy (Kurzynska-Kokorniak et al., 2009; Moens, 2009). By silencing the action of these viral miRNAs the host cell may be able to gain control and/or eliminate the virus.

We have previously shown that HCMV alters cellular miRNA expression to benefit its own replication (Wang et al., 2008). HCMV also has immune modulating effects in human tissues, which has significant clinical impact in organ transplant recipients, where HCMV infection increases risk of graft versus host disease and vice-versa (Sing and Ruscetti, 1995). miRNAs also play important roles in regulating both adaptive and innate immunity, including controlling the differentiation of various immune cell subsets as well as their functions (Lu and Liston, 2009). The HCMV-miRNA interactions may also play a role in immune modulation by the virus, possible regulating outcomes such as graft versus host disease. Thus, understanding the miRNA-HCMV virus interactions may pave the way to development of a novel class of therapeutic targets against this virus and its various deleterious effects in humans.

8.3. miRNAs and congenital HCMV infection

With an estimated 40,000 children born with congenital HCMV infections in the United States, it is the leading cause of congenital infections in the United States (Cannon and Davis, 2005). About 90% of these children are asymptomatic at birth and 10–15% of them subsequently develop symptoms such as hearing loss and mental retardation. Because there is no proven method for prevention of transmission, routine CMV testing during pregnancy is not recommended; testing is recommended only when a fetal anomaly is detected, a pregnant woman experiences a mononucleosis-like illness, or a pregnant woman requests the test (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2008).

Placental miRNA signatures have been identified in patients with pre-eclampsia and cigarette smoking-related fetal growth reduction (Maccani et al., 2010; Zhu et al., 2009). miRNA signatures can be assessed in placentas of patients giving birth to symptomatic and asymptomatic congenital HCMV infections. Such expression signatures may help identify patients with congenital HCMV who are asymptomatic at birth and at risk for developing symptoms later in life, enabling monitoring and earlier intervention. Another possibility is to identify ante-natal miRNA signatures due to HCMV infection of the placenta in maternal samples such as plasma/amniotic fluid.

9. Future perspectives

Studies of the roles of miRNAs in HCMV infection are still in their early stages. Several areas are ripe for immediate investigation.

Detailed transcript maps are not available for most of the HCMV genome and we do not know the nature of the primary transcripts from which the HCMV miRNAs arise. It is not known whether any HCMV miRNAs are expressed during latency (Skalsky and Cullen, 2010). A combination of approaches is needed that includes deep sequencing, use of tiled oligonucleotide arrays that span the genome, and targeted precise 5′ and 3′ mapping of individual transcripts. It will also be necessary to use low passage viruses that have as close to a full complement of wild-type genes as is possible, to examine a variety of cell types that are relevant to infections in vivo (such as from an in vitro model of latency (Goodrum et al., 2002), as well as endothelial and epithelial cells), and to explore cells and tissues obtained from HCMV-infected humans.

We need to learn the effects of HCMV infection on miRNA biogenesis. As illustrated by the differences in expression of the miR-UL36-1 pre- and mature miRNAs, HCMV infection influences at least some step of miRNA biogenesis (Grey et al., 2005). We also need to understand the mechanisms that regulate transcription of individual miRNAs during infection. and the relationship of the microprocessor to nuclear replication compartments during HCMV infection.

RISC-based immunoprecipitation experiments have proven informative in uninfected cells that express viral miRNAs (Grey et al., 2010); similar screens are needed of infected cells.

Reasonably clear paths are available for addressing the issues listed above. The challenging long-term problem will be to learn the biological roles of miRNAs during HCMV infection. Systems approaches will be important at the early stages of this exploration, but in the end, the significant advances will be the product of creative, focused analysis of small sets of miRNAs and their effects on particular biological pathways.

Fig. 5.

HCMV management of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway. The schematic illustrates some of the major inputs and regulatory control points along the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, including points where HCMV is known to exert influence (indicated in blue) (Alwine, 2008; Buchkovich et al., 2008). The two mTOR-containing complexes, mTORC1 and mTORC2 are indicated in red. As described in the text, levels of mTOR, Rictor, and Raptor may be regulated in part by miRNAs that are downregulated after HCMV infection (Wang et al., 2008). Dashed lines and objects indicate the loss of inhibitory subunits, which is required as part of activation of mTORC1 and eIF4E.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Wayne State University and a grant from the National Institutes of Health (5R21 AI064907). We thank Dr. Fayth Yoshimura for helpful comments.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Kavitha Dhuruvasan, Email: kdhuruva@med.wayne.edu.

Geetha Sivasubramanian, Email: geejag@gmail.com.

References

- Alexiou P, Maragkakis M, Papadopoulos GL, Reczko M, Hatzigeorgiou AG. Lost in translation: an assessment and perspective for computational microRNA target identification. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:3049–3055. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alwine JC. Modulation of host cell stress responses by human cytomegalovirus. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2008;325:263–279. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-77349-8_15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baek D, Villen J, Shin C, Camargo FD, Gygi SP, Bartel DP. The impact of microRNAs on protein output. Nature. 2008;455:64–71. doi: 10.1038/nature07242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbato C, Arisi I, Frizzo ME, Brandi R, Da SL, Masotti A. Computational challenges in miRNA target predictions: to be or not to be a true target? J Biomed Biotechnol. 2009;2009:803069. doi: 10.1155/2009/803069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartels CL, Tsongalis GJ. MicroRNAs: novel biomarkers for human cancer. Clin Chem. 2009;55:623–631. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.112805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth S, Pfuhl T, Mamiani A, Ehses C, Roemer K, Kremmer E, Jaker C, Hock J, Meister G, Grasser FA. Epstein-Barr virus-encoded microRNA miR-BART2 down-regulates the viral DNA polymerase BALF5. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:666–675. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm1080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellare P, Ganem D. Regulation of KSHV lytic switch protein expression by a virus-encoded microRNA: an evolutionary adaptation that fine-tunes lytic reactivation. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;6:570–575. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeckh M, Boivin G. Quantitation of cytomegalovirus: methodologic aspects and clinical applications. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:533–554. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.3.533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeckh M, Ljungman P. How we treat cytomegalovirus in hematopoietic cell transplant recipients. Blood. 2009;113:5711–5719. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-143560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogerd HP, Karnowski HW, Cai X, Shin J, Pohlers M, Cullen BR. A mammalian herpesvirus uses noncanonical expression and processing mechanisms to generate viral MicroRNAs. Mol Cell. 2010;37:135–142. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boss IW, Plaisance KB, Renne R. Role of virus-encoded microRNAs in herpesvirus biology. Trends Microbiol. 2009;17:544–553. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breving K, Esquela-Kerscher A. The complexities of microRNA regulation: mirandering around the rules. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchkovich NJ, Yu Y, Zampieri CA, Alwine JC. The TORrid affairs of viruses: effects of mammalian DNA viruses on the PI3K-Akt-mTOR signalling pathway. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6:266–275. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buck AH, Santoyo-Lopez J, Robertson KA, Kumar DS, Reczko M, Ghazal P. Discrete clusters of virus-encoded microRNAs are associated with complementary strands of the genome and the 7.2-kilobase stable intron in murine cytomegalovirus. J Virol. 2007;81:13761–13770. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01290-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai X, Lu S, Zhang Z, Gonzalez CM, Damania B, Cullen BR. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus expresses an array of viral microRNAs in latently infected cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:5570–5575. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408192102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon MJ, Davis KF. Washing our hands of the congenital cytomegalovirus disease epidemic. BMC Public Health. 2005;5:70. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-5-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao P, Deng Z, Wan M, Huang W, Cramer SD, Xu J, Lei M, Sui G. MicroRNA-101 negatively regulates Ezh2 and its expression is modulated by androgen receptor and HIF-1alpha/HIF-1beta. Mol Cancer. 2010;9:108. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Knowledge and practices of obstetricians and gynecologists regarding cytomegalovirus infection during pregnancy--United States, 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2008;57:65–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha TA, Tom E, Kemble GW, Duke GM, Mocarski ES, Spaete RR. Human cytomegalovirus clinical isolates carry at least 19 genes not found in laboratory strains. J Virol. 1996;70:78–83. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.1.78-83.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaisuparat R, Hu J, Jham BC, Knight ZA, Shokat KM, Montaner S. Dual inhibition of PI3Kalpha and mTOR as an alternative treatment for Kaposi’s sarcoma. Cancer Res. 2008;68:8361–8368. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers JW, Maguire TG, Alwine JC. Glutamine metabolism is essential for human cytomegalovirus infection. J Virol. 2010;84:1867–1873. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02123-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choy EY, Siu KL, Kok KH, Lung RW, Tsang CM, To KF, Kwong DL, Tsao SW, Jin DY. An Epstein-Barr virus-encoded microRNA targets PUMA to promote host cell survival. J Exp Med. 2008;205:2551–2560. doi: 10.1084/jem.20072581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooray S. The pivotal role of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-Akt signal transduction in virus survival. J Gen Virol. 2004;85:1065–1076. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.19771-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosman D, Mullberg J, Sutherland CL, Chin W, Armitage R, Fanslow W, Kubin M, Chalupny NJ. ULBPs, novel MHC class I-related molecules, bind to CMV glycoprotein UL16 and stimulate NK cytotoxicity through the NKG2D receptor. Immunity. 2001;14:123–133. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00095-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creighton CJ, Reid JG, Gunaratne PH. Expression profiling of microRNAs by deep sequencing. Brief Bioinform. 2009;10:490–497. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbp019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Alessandra Y, Devanna P, Limana F, Straino S, Di CA, Brambilla PG, Rubino M, Carena MC, Spazzafumo L, De SM, Micheli B, Biglioli P, Achilli F, Martelli F, Maggiolini S, Marenzi G, Pompilio G, Capogrossi MC. Circulating microRNAs are new and sensitive biomarkers of myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J. 2010 doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dargan DJ, Douglas E, Cunningham C, Jamieson F, Stanton RJ, Baluchova K, McSharry BP, Tomasec P, Emery VC, Percivalle E, Sarasini A, Gerna G, Wilkinson GW, Davison AJ. Sequential mutations associated with adaptation of human cytomegalovirus to growth in cell culture. J Gen Virol. 2010;91:1535–1546. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.018994-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das S, Vasanji A, Pellett PE. Three-dimensional structure of the human cytomegalovirus cytoplasmic virion assembly complex includes a reoriented secretory apparatus. J Virol. 2007;81:11861–11869. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01077-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison AJ, Dargan DJ, Stow ND. Fundamental and accessory systems in herpesviruses. Antiviral Res. 2002;56:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(02)00107-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison AJ, Dolan A, Akter P, Addison C, Dargan DJ, Alcendor DJ, McGeoch DJ, Hayward GS. The human cytomegalovirus genome revisited: comparison with the chimpanzee cytomegalovirus genome. J Gen Virol. 2003;84:17–28. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.18606-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doghman M, El WA, Cardinaud B, Thomas E, Wang J, Zhao W, Peralta-Del Valle MH, Figueiredo BC, Zambetti GP, Lalli E. Regulation of insulin-like growth factor-mammalian target of rapamycin signaling by microRNA in childhood adrenocortical tumors. Cancer Res. 2010;70:4666–4675. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan A, Cunningham C, Hector RD, Hassan-Walker AF, Lee L, Addison C, Dargan DJ, McGeoch DJ, Gatherer D, Emery VC, Griffiths PD, Sinzger C, McSharry BP, Wilkinson GW, Davison AJ. Genetic content of wild-type human cytomegalovirus. J Gen Virol. 2004;85:1301–1312. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.79888-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolken L, Perot J, Cognat V, Alioua A, John M, Soutschek J, Ruzsics Z, Koszinowski U, Voinnet O, Pfeffer S. Mouse cytomegalovirus microRNAs dominate the cellular small RNA profile during lytic infection and show features of posttranscriptional regulation. J Virol. 2007;81:13771–13782. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01313-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolken L, Pfeffer S, Koszinowski UH. Cytomegalovirus microRNAs. Virus Genes. 2009;38:355–364. doi: 10.1007/s11262-009-0347-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn C, Chalupny NJ, Sutherland CL, Dosch S, Sivakumar PV, Johnson DC, Cosman D. Human cytomegalovirus glycoprotein UL16 causes intracellular sequestration of NKG2D ligands, protecting against natural killer cell cytotoxicity. J Exp Med. 2003a;197:1427–1439. doi: 10.1084/jem.20022059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn W, Chou C, Li H, Hai R, Patterson D, Stolc V, Zhu H, Liu F. Functional profiling of a human cytomegalovirus genome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003b;100:14223–14228. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2334032100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn W, Trang P, Zhong Q, Yang E, van Belle C, Liu F. Human cytomegalovirus expresses novel microRNAs during productive viral infection. Cell Microbiol. 2005;7:1684–1695. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fannin Rider PJ, Dunn W, Yang E, Liu F. Human cytomegalovirus microRNAs. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2008;325:21–39. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-77349-8_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furnari FB, Adams MD, Pagano JS. Unconventional processing of the 3′ termini of the Epstein-Barr virus DNA polymerase mRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:378–382. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.2.378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodrum FD, Jordan CT, High K, Shenk T. Human cytomegalovirus gene expression during infection of primary hematopoietic progenitor cells: a model for latency. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:16255–16260. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252630899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grey F, Antoniewicz A, Allen E, Saugstad J, McShea A, Carrington JC, Nelson J. Identification and characterization of human cytomegalovirus-encoded microRNAs. J Virol. 2005;79:12095–12099. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.18.12095-12099.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grey F, Meyers H, White EA, Spector DH, Nelson J. A human cytomegalovirus-encoded microRNA regulates expression of multiple viral genes involved in replication. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e163. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grey F, Nelson J. Identification and function of human cytomegalovirus microRNAs. J Clin Virol. 2008;41:186–191. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2007.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grey F, Tirabassi R, Meyers H, Wu G, McWeeney S, Hook L, Nelson JA. A viral microRNA down-regulates multiple cell cycle genes through mRNA 5′UTRs. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000967. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths-Jones S. The microRNA Registry. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(Database issue):D109–D111. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundhoff A, Sullivan CS, Ganem D. A combined computational and microarray-based approach identifies novel microRNAs encoded by human gamma-herpesviruses. RNA. 2006;12:733–750. doi: 10.1261/rna.2326106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakki M, Geballe AP. Double-stranded RNA binding by human cytomegalovirus pTRS1. J Virol. 2005;79:7311–7318. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.12.7311-7318.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay N, Sonenberg N. Upstream and downstream of mTOR. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1926–1945. doi: 10.1101/gad.1212704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill JM, Zhao Y, Clement C, Neumann DM, Lukiw WJ. HSV-1 infection of human brain cells induces miRNA-146a and Alzheimer-type inflammatory signaling. Neuroreport. 2009;20:1500–1505. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3283329c05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt EA, Goulding AM, Deo SK. Direct detection and quantification of microRNAs. Anal Biochem. 2009;387:1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2009.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jopling CL, Yi M, Lancaster AM, Lemon SM, Sarnow P. Modulation of hepatitis C virus RNA abundance by a liver-specific MicroRNA. Science. 2005;309:1577–1581. doi: 10.1126/science.1113329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kearns AM, Draper B, Wipat W, Turner AJ, Wheeler J, Freeman R, Harwood J, Gould FK, Dark JH. LightCycler-based quantitative PCR for detection of cytomegalovirus in blood, urine, and respiratory samples. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39:2364–2365. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.6.2364-2365.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller A, Leidinger P, Lange J, Borries A, Schroers H, Scheffler M, Lenhof HP, Ruprecht K, Meese E. Multiple sclerosis: microRNA expression profiles accurately differentiate patients with relapsing-remitting disease from healthy controls. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7440. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurzynska-Kokorniak A, Jackowiak P, Figlerowicz M, Figlerowicz M. Human- and virus-encoded microRNAs as potential targets of antiviral therapy. Mini Rev Med Chem. 2009;9:927–937. doi: 10.2174/138955709788681573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lagos D, Pollara G, Henderson S, Gratrix F, Fabani M, Milne RS, Gotch F, Boshoff C. miR-132 regulates antiviral innate immunity through suppression of the p300 transcriptional co-activator. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:513–519. doi: 10.1038/ncb2054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanford RE, Hildebrandt-Eriksen ES, Petri A, Persson R, Lindow M, Munk ME, Kauppinen S, Orum H. Therapeutic silencing of microRNA-122 in primates with chronic hepatitis C virus infection. Science. 2010;327:198–201. doi: 10.1126/science.1178178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Xu J, Yang D, Tan X, Wang H. Computational approaches for microRNA studies: a review. Mamm Genome. 2010;21:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s00335-009-9241-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu DZ, Tian Y, Ander BP, Xu H, Stamova BS, Zhan X, Turner RJ, Jickling G, Sharp FR. Brain and blood microRNA expression profiling of ischemic stroke, intracerebral hemorrhage, and kainate seizures. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009 doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2009.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Sall A, Yang D. MicroRNA: an emerging therapeutic target and intervention tool. Int J Mol Sci. 2008;9:978–999. doi: 10.3390/ijms9060978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu LF, Liston A. MicroRNA in the immune system, microRNA as an immune system. Immunology. 2009;127:291–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2009.03092.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maccani MA, vissar-Whiting M, Banister CE, McGonnigal B, Padbury JF, Marsit CJ. Maternal cigarette smoking during pregnancy is associated with downregulation of miR-16, miR-21 and miR-146a in the placenta. Epigenetics. 2010:5. doi: 10.4161/epi.5.7.12762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamane Y, Petroulakis E, LeBacquer O, Sonenberg N. MTOR, translation initiation and cancer. Oncogene. 2006;25:6416–6422. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannova P, Beretta L. Activation of the N-Ras-PI3K-Akt-mTOR pathway by hepatitis C virus: control of cell survival and viral replication. J Virol. 2005;79:8742–8749. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.14.8742-8749.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]