Abstract

Objective

We examined cardiometabolic disease and mortality over eight years among individuals with and without schizophrenia.

Method

We compared 65,362 patients in the Veteran Affairs (VA) health system with schizophrenia to 65,362 VA patients without serious mental illness (non-SMI) matched on age, service access year, and location. The annual prevalence of diagnosed cardiovascular disease, diabetes, dyslipidemia, hypertension, obesity, and all-cause and cause-specific mortality were compared for fiscal years 2000–2007. Mean years of potential life lost (YPLL) was calculated annually.

Results

The cohort was mostly male (88%) with a mean age of 54 years. Cardiometabolic disease prevalence increased in both groups with non-SMI patients having higher disease prevalence in most years. Annual between-group differences ranged from < 1% to 6%. Annual mortality was stable over time for schizophrenia (3.1%) and non-SMI patients (2.6%). Annual mean YPLL increased from 12.8 to 15.4 in schizophrenia and from 11.8 to 14.0 for non-SMI groups.

Conclusions

VA patients with and without schizophrenia show increasing but similar prevalence rates of cardiometabolic diseases. YPLLs were high in both groups and only slightly higher among patients with schizophrenia. Findings highlight the complex population served by the VA while suggesting a smaller mortality impact from schizophrenia than previously reported.

Keywords: schizophrenia, cardiovascular disease, morbidity, mortality, cardiometabolic

Introduction

Researchers estimate that individuals with schizophrenia have a life expectancy 15–30 years shorter than the general population [1, 2]. This disparity has been observed consistently in clinical and population-based studies in the U.S. and elsewhere [3–7]. Although some excess mortality is due to trauma and suicide, the majority has been associated with natural causes, such as cancer, respiratory diseases, and most notably, cardiovascular disease (CVD) [2, 8]. Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of premature mortality in persons with schizophrenia with cancer-related deaths reported nearly as frequently in some studies [2, 9], a trend consistent with the leading causes of death among the general U.S. population [11].

Premature mortality from natural causes of death among people with schizophrenia is commonly attributed to socioeconomic factors (e.g., poverty, poor education), behavioral factors (e.g., cigarette smoking, physical inactivity) and treatment factors (e.g., fragmentation of physical and mental health care, disparities in quality of medical care) and possibly to the cardiometabolic side effects of atypical antipsychotic medications [12–15]. However, the increased risk for CVD mortality existed prior to the advent of atypical antipsychotics, with some evidence indicating that first-generation antipsychotic medications might confer a greater risk for premature mortality [13]. Epidemiological evidence from time-trend studies and meta-analyses suggests that rates of premature death among individuals with schizophrenia have increased over the past three decades [3, 16, 17] although recent studies indicate that these rates may be in decline in settings with better mental health care [2, 18].

Approximately 3.5 million adults in the US have schizophrenia (1.5% of U.S adult population) [19, 20]. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) recognizes the need to reduce health and health care disparities for individuals with mental illness and in 2010 set a goal of reducing premature mortality by 10 years within 10 years [21]. Some have suggested health insurance reforms may diminish disparities through expansion of publicly-funded insurance programs at the state level [22]. To more fully understand the health needs of people with schizophrenia and care delivery models that may be effective for them, it is essential to understand the current and recent health states of this population.

Published studies addressing excess mortality among individuals with serious mental illness, and cardiometabolic morbidity and mortality specifically in people with schizophrenia, have been relatively small, with cohorts ranging from 72 to 7217 subjects, and either cross-sectional or with a limited follow-up [3, 7, 23]. Until recently, the literature lacked prospective cohort studies conducted at a population level that apply national patient registries to monitor changes in cardiovascular risk factors and mortality over time. Moreover, even in studies from countries with national data registries, results are difficult to interpret due to the absence of comparison groups that are matched by appropriate demographic characteristics [2].

The goals of this study were to examine the unadjusted crude prevalence rates and trends of five cardiometabolic morbidities as well as trends in overall and cause-specific, unadjusted crude mortality rates associated with schizophrenia for a national cohort spanning 8 years. Our large cohort consisted of individuals receiving care from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) health system. The VA health system is one of the largest providers of care to people with mental illness in the U.S. With a national electronic medical record system, integrated care design, and emphasis on care of the mentally ill, the VA represents a unique context to examine trends in morbidity and mortality of people with schizophrenia [24, 25].

Method

Setting and Design

Subjects with schizophrenia were identified from the VA National Psychosis Registry (NPR). Details of this registry have been described elsewhere [26]. Briefly, the registry includes administrative records for all VA patients who have received a diagnosis of psychosis in inpatient settings at some point since fiscal year (FY) 1988 or in outpatient settings since FY1997. The registry includes records of patient demographics, inpatient and outpatient services use, diagnoses, and prescription medication dispensing, vital signs and laboratory results.

From the NPR, our study cohort included patients with one or more diagnoses of schizophrenia in inpatient or outpatient settings from fiscal year (FY) 2000 through FY 2007 (10/1/99-9/30/07) (See Appendix for ICD-9 codes). We excluded patients with dementia diagnoses prior to the first diagnosis of schizophrenia as we believe these patients represent a distinct population with distinct care patterns and needs. A comparison population of VA patients was identified from annual random-sample cohorts of patients maintained in conjunction with NPR. This was achieved by matching each patient with one randomly selected comparison patient of the same age (within 2 years), sex, a VA clinic or inpatient visit within the same VA medical center system within 6 months of the schizophrenia patient's index diagnosis date, and with no diagnosis of serious mental illness (schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or other psychosis diagnosis) in the study period.

Outcome measures

The main outcomes were 1) annual prevalence of cardiometabolic diseases: diabetes mellitus type 2 (T2DM), hypertension (HTN), dyslipidemia, and cardiovascular disease (CVD); 2) obesity, determined by Body Mass Index (BMI); and 3) rates of all-cause and cause-specific mortality. Year and cause of death were obtained from National Death Index data. These data are requested annually for all patients who did not have VA health care utilization in FY 2008 or 2009 [27, 28]. To determine annual prevalence of each of four cardiometabolic disease states, we identified diseases using ICD-9 diagnosis codes and prescription medication fills. Patients having either a diagnosis or a prescription fill specific to the disease of interest (e.g. oral hypoglycemic agents were deemed indicative of T2DM) were classified as having the corresponding condition. The diagnosis or medication fill date that occurred earliest in the study period was considered the index date of onset of the disease. Once a patient was classified as having a disease (except for obesity) we assumed the condition continued in all study follow-up years.

Obesity was defined as having a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30. BMI was calculated from height and weight measures obtained from the VA vital signs files included among NPR data holdings. Patients categorized as obese in a given year were not assumed to be obese in subsequent years; for each year, they were categorized as obese only if a height and weight were recorded and BMI was 30 or greater.

Patient and Care System Characteristics

Covariates included in descriptive analyses were patient age, race (categorized as black, white, Hispanic and other), sex, Category C cost-share status (a VA measure of income sufficient to pay cost-share), military service connected disability status (a VA indicator of illness related to military service), marital status (dichotomized as married, not-married), and non-SMI psychiatric comorbidities (post traumatic stress disorder [PTSD], anxiety, depression, substance abuse or dependence). Tobacco exposure was based on diagnoses of chronic obstructive lung disease and/or tobacco use. Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) was assigned based on the site of the index diagnosis of schizophrenia or of index visit for the comparison population. Further methods details are provided in the Appendix.

Follow-up and censoring

Patients were followed from their index date through the end of the study period, 9/30/2007, or until they met one of the following censoring criteria: (1) no VA visits for 13 months (censored 12 months from last recorded visit or prescription fill), (2) death date identified from the NDI, (3) admission to a VA community living center (formerly known as nursing homes) lasting more than 30 days (patients were censored 30 days after admission)

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to compare the schizophrenia and comparison population with regard to demographic characteristics, non-SMI psychiatric diagnoses, tobacco exposure, and inpatient and outpatient services use. Comparisons were conducted using methods for paired designs such as paired t-tests. For each year and group, we calculated the prevalence of each cardiometabolic morbidity, proportion of the group with BMI ≥ 30, and annual all-cause and cause-specific mortality.

The number of years of potential life lost (YPLL) was calculated for each decedent using current life expectancy tables for the U.S. population, published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [29]. This measure of premature death uses the difference between a patient's age at death and the current life expectancy for cohorts of the same age and sex as the decedent in the year of death. Individual-level YPLL were used to calculate annual mean YPLL for each group (schizophrenia and non-SMI) by summing all YPLL in each group and dividing the sum by the number of group members decedents each year [10]. We also calculated the mean age at death for each group. YPLL was performed to put our observation comparing two VA populations into the context of the general U.S. population.

Results

We identified 65,362 patients with schizophrenia meeting inclusion criteria and an equal number of matched non-SMI comparison patients. Mean (SD) age was 53.6 years (14.8), 87.9% were male, and 32.1% were ethnic/racial minorities (Table 1). Race and income distribution differed somewhat between the schizophrenia and comparison groups. Among patients with schizophrenia, 27.9% were black, 13.2% met Category C income criteria, and 27.0% were married; this compares to the non-SMI group in which 19.9% of patients were black, 26.3% met Category C income criteria, and 45.9% were married. Substance abuse, tobacco use/tobacco related disease, and cumulative prevalence of non-SMI mental illness (anxiety, depression) were all more common in the schizophrenia group than the comparison group. Patients with schizophrenia used inpatient and outpatient services more intensely than the comparison group as well.

Table 1.

Demographics, Psychiatric Comorbidities and Service Use of Patients with Schizophrenia and the Comparison Population with No Serious Mental Illness 2000–2007

| Characteristics | Overall (N=130,724) | Schizophrenia Group (N=65,362) | Non-SMI Comparison Group (N=65,362) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age SD | 53.6 (14.8)* | 53.4 (14.9) | 53.8(14.6) |

| White: N (%) | 78220 (67.9)* | 37960 (64.2) | 40260(72.0) |

| Black: N (%) | 27608 (23.9) | 16470 (27.9) | 11138(19.9) |

| Hispanic: N (%) | 6184 (5.4) | 3099 (5.2) | 3085(5.5) |

| Other Race: N (%) | 3054 (2.7) | 1619 (2.7) | 1435(2.6) |

| Male: N (%) | 115006 (87.9) | 57503 (87.9) | 57503(87.9) |

| Meets Category C Cost Share Means Test: N (%) | 24850 (19.7)* | 8408 (13.2) | 16442(26.3) |

| Service Connected: N (%) | 62317 (47.7)* | 31928 (48.9) | 30389(46.5) |

| Married: N (%) | 47507 (36.5)* | 17493 (27.0) | 30014(45.9) |

| Substance Abuse Disorder Diagnosis: N (%) | 39618 (30.3)* | 26442 (40.5) | 13176(20.2) |

| Post Traumatic Stress Disorder: N (%) | 29074 (22.2)* | 16026 (24.5) | 13048(19.9) |

| Anxiety not PTSD: N (%) | 30936 (23.7)* | 17979 (27.5) | 12957(19.8) |

| Depression: N (%) | 71243 (54.5)* | 37413 (57.2) | 33830(51.8) |

| Tobaccos Exposure Diagnoses: N (%) | 45675 (34.9)* | 27005 (41.3) | 18670(28.6) |

| No-Mental Illness Diagnosis: N (%) | 47579(72.8) | ||

| Inpatient and Outpatient Service Use | |||

| Psychiatric inpatient days/person year | 1.84 | 3.52 | 0.19 |

| Non-Psychiatric inpatient days/person years | 2.95 | 4.27 | 1.65 |

| Psychiatric outpatient clinic visits/person year | 9.89 | 15.83 | 4.04 |

| Non-Psychiatric outpatient clinic visits/person year | 18.05 | 20.39 | 15.74 |

Tobacco exposure measure is defined as a diagnosis of tobacco-associated lung disease or diagnosis of tobacco use. Category C is a Veterans Administration means tested benefit categorization, Category C patients have sufficient income to be held responsible for cost-share payments on select services. Prevalence of psychiatric and tobacco associated comorbidities presented are cumulative over the 8-year study period. Inpatient and outpatient service use rates presented are calculated for all patients during all years. Chi squared and T tests used to determine statistical difference across groups.

Indicates p< 0.05.

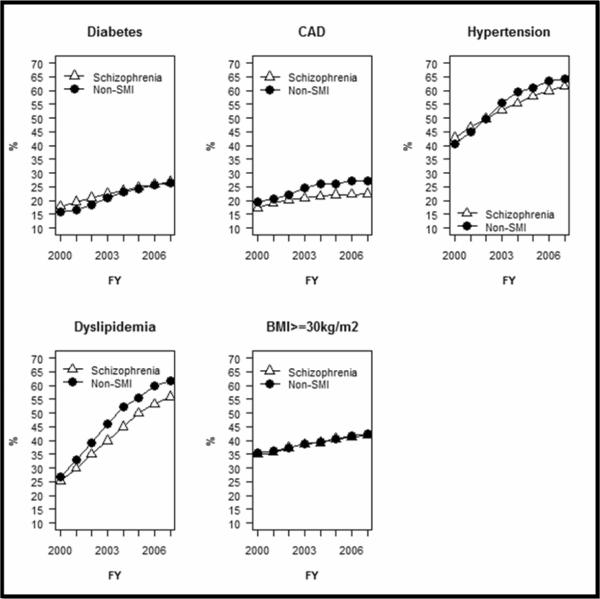

Figure 1 (and Appendix Table 2) presents morbidity measures by year. In the earlier years, diabetes and obesity were more prevalent among the schizophrenia group relative to the comparison group. T2DM affected 17.9% to 21.1% of the schizophrenia group in the first three study years and 15.8% to 18.5% of the comparison group. In the early years, the prevalence of obesity was also greater among the schizophrenia patients (25.6% to 29.2%) relative to the comparison group (24.1% to 27.7%). These differences diminished in later years. In all years, prevalence of diagnosed HTN, CAD, and hyperlipidemia were consistently lower in the schizophrenia group than the comparison group. In 2007, the prevalence of diagnosed CAD was 22.4% in the schizophrenia population and 27.1% in the comparison group. Both groups experienced a substantial increase in cardiometabolic diagnoses over the study period. Notably diagnosed dyslipidemia nearly doubled from 25.2% of the schizophrenia group and 26.9% of the comparison group in 2000 to 55.9% and 61.7%, respectively in 2007.

Figure 1. Annual Prevalence of Diagnosed Cardiometabolic Diseases Among Veterans with Schizophrenia and a Matched Comparison Group of Veterans Without Serious Mental Illness 2000–2007.

Non-SMI group is matched on age, gender, parent Veterans Administration medical center and visit date, and has no diagnosis of psychotic disorder. Annual prevalence based on ICD-9 diagnoses and disease-specific pharmacotherapy. Once diagnosed patients with chronic conditions are assumed to continue with that condition until death or censorship. Annual prevalence of obesity is based on annual body mass index ≥30 kg/m2. Patients obese in one year are not assumed obese in subsequent years. FY = fiscal year, CAD= Coronary Artery Disease, BMI = Body Mass Index (weight in kilograms/height in meters squared). See appendix table 1 for annual rates.

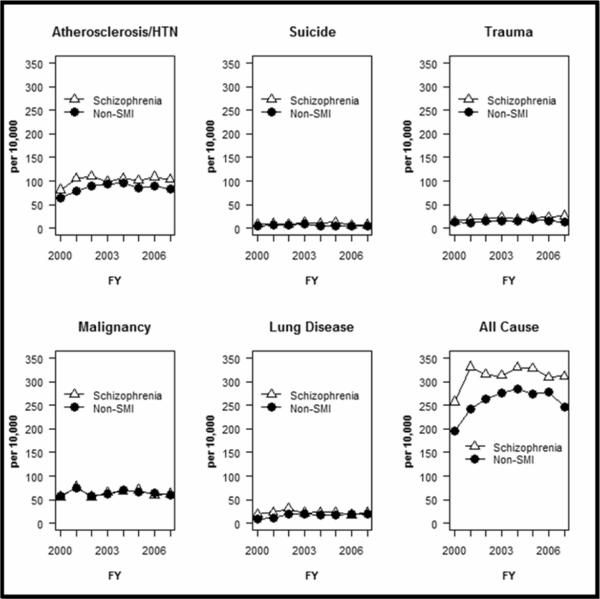

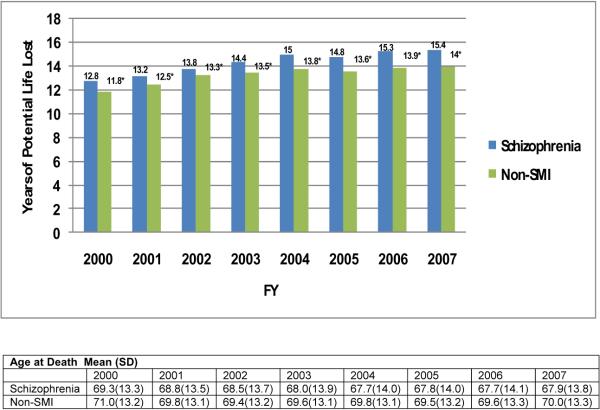

Compared to cardiometabolic morbidity, mortality rates varied more substantially across the two groups. The schizophrenia group experienced significantly higher rates of mortality due to all-causes as well as from trauma/accidents in nearly all years and from suicide in most years. (Figure 2, Table 2). For all-cause mortality, the difference in annual rates never exceeded 0.9% between the cohorts. The most substantial difference across groups in annual all cause-mortality occurred in 2003 when schizophrenia patients experienced a death rate 1.6% higher than the comparison population. Annual mean YPLL increased from 12.8 to 15.4 for schizophrenia patients and from 11.8 to 14.0 for non-SMI patients, in each year the difference between the two populations was statistically significant (p< 0.01) (See Figure 3).

Figure 2. Annual Death Rate per 10,000 Person Years Overall and by Specific Causes, for Veterans with Schizophrenia and a Matched Comparison Group of Veterans without Serious Mental Illness, 2000–2007.

Non-SMI group is matched on age, gender, parent Veterans Administration medical center and visit date. Non-SMI comparison group has no diagnosis of psychotic disorder (schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or other psychosis). Cause of death as categorized by the National Death Index Plus data. Deaths attributed to “atherosclerotic/HTN” are those categorized in this data set as death due to: atherosclerosis hypertension, coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, and aortic aneurysm. Annual mortality rates are presented in Appendix Table 2.

Figure 3. Years of Potential Life Lost and Age at Death, 2000–2007, for Veterans with Schizophrenia and a Matched Comparison Population with no Serious Mental Illness.

The number of years of potential life lost (YPLL) was calculated for each decedent using current life expectancy tables for the U.S. population, published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This measure of premature death uses the difference between a patient's age at death and the current life expectancy for cohorts of the same age and sex as the decedent in the year of death. Individual-level YPLL were used to calculate annual mean YPLL for each group (schizophrenia and non-SMI) by summing all YPLL in each group and dividing the sum by the number of group members decedents each year.[1] We also calculated the mean age at death for each group. T-test was used to assess statistical significance between groups. * denotes p< 0.01

Discussion

Our large, retrospective study of the prevalence of cardiometabolic disease as well as all-cause and cause-specific mortality rates among patients diagnosed with schizophrenia relative to a matched comparison cohort revealed unexpectedly small overall differences across the cohorts in morbidity and mortality. While there were significantly higher annual mortality rates in the schizophrenia group the overall mortality-gap with comparison group was not as large as reported in the literature. The difference in the all-cause mortality rates of the two cohorts over the 8-year observation period appears predominantly attributable to mortality from atherosclerosis/HTN, suicide, and other causes that are consistently more common among the schizophrenia patients compared to the comparison population.

We find an overall increase in cardiometabolic disease for both the schizophrenia and the comparison populations. This is likely due to many factors including intensified screening and lower diagnostic thresholds (for T2DM for example). The observed increasing prevalence of obesity mirrors that of the general U.S. population and likely explains at least some of the rise in prevalence of other morbidities for which obesity is an important risk factor [30, 31]. For some cardiometabolic conditions, prevalence was lower in the schizophrenia group than the comparison group despite substantially higher rates of tobacco exposure, comparable rates of obesity, and the added cardiometabolic risk associated with some second generation antipsychotics. This may result from lower levels of diagnostic testing in this population, due in part to the clinical demands of managing mental illness. Although schizophrenia patients had higher rates of health care encounters (psychiatric and non-psychiatric) compared to the non-SMI group, these encounters may focus on acute conditions or consequences of mental illness rather than screening and prevention which may explain some differences in documented disease prevalence [32, 33]. While lower rates of testing may explain relative low prevalence of some diseases in the schizophrenia population, the modest differences in cardiometabolic mortality suggest that disease prevalence in the two populations is not dramatically different [34].

Rates of much morbidity in the schizophrenia group are comparable with non-SMI Veteran population, yet for both groups, rates were significantly greater than the general U.S. population. For example, the prevalence of diabetes and obesity (BMI≥30) in 2005 for men between the ages of 40–59 years old averaged 7.9% and 39.7% respectively in objectively measured samples of American adults [35, 36], whereas the concurrent rates in the cohort of non-SMI Veterans averaged 24.1% and 40.7% and 24.9% and 40.6% in the schizophrenia group. VHA FY 2010 operational data indicate that the combined prevalence of overweight/obesity is 77% among VA patients (39% for obesity only), 10% greater than the general U.S. population [37]. These figures underscore the morbidity burden in the VA patient population that distinguishes it from general U.S. population and validate our choice of Veterans without SMI as the best comparison population.

Mortality is a critical measure of effectiveness of specific clinical treatment strategies [2, 16]. Our findings support conclusions of a 2009 publication reporting a 1.5-year difference in life expectancy among the general population of VA patients with and without SMI [38]. Likewise, a 2010 survey-based publication [39] comparing the mortality for VA patients with and without schizophrenia found that the hazards ratio for death for Veterans with schizophrenia compared to those with no mental illness was 1.2, significantly lower than the average 2.5 mortality ratio reported in community samples [3]. The similar rates in mortality among Veterans with and without SMI treated through VA healthcare facilities contrasts reports of a life expectancy gap of over 20–30 years among persons with schizophrenia compared to the general population even in settings with socialized medicine including the Nordic countries and Taiwan [6, 7, 18]. Gaps in mortality of this magnitude among people with serious mental illnesses have also been observed in the U.S. and in other countries [1, 3, 13].

While not the primary focus of the current study, mortality rates for cancer and suicide were notably lower than reported in other studies [2, 9, 40]. A number of methodological issues can obscure clear comparisons between the causes of mortality from suicide or specific cancers including the age of the cohort, the length and decade of follow-up, the cohort size, patient access to quality integrated and preventive health care services, and the reliability of data to measure causes of death. However, crude and unadjusted mortality findings from the current study are consistent with results from a recent retrospective study [41] examining causes of death and years of potential life lost (YPLL) among decedents with a serious mental illness persons from the general population in a Midwestern U.S. state. Researchers found that heart disease was the leading cause of death in both groups while cancer was the second leading cause of death in the general population but only the fifth cause of death for SMI patients (suicide was not in the top 10 causes of death for SMI patients overall). However, suicide, accidents, and cancer were leading causes of premature mortality (YPLL), causing the authors to conclude that community mental health clinics should place more emphasis on integrated care and preventive screening for these risks. In addition, mortality and morbidity results from the current study not only parallel similar findings reported by Bouza and colleagues in Spain [42], but also the leading cause of death (CVD) and mortality gap (i.e., 8 years) in a community-based study of American patients with mental disorders published by Druss et al. [43]

Indeed the relatively small disparities observed for patients within VA may be due to the unique, nationally and regionally integrated nature of this system. The VA's nationally integrated health care system is unique compared to other national health systems because of the high-risk population that the VA serves. Unlike many health systems, patients not only have access to mental and physical health care, but also receive targeted services to screen for and prevent both suicide and many forms of common cancers that might be attributed to exposures incurred during military service. The VA has made integrated care a priority for patients with psychotic disorders since landmark studies were published in 2001 suggesting this approach improves outcomes [33, 44]. Patients with schizophrenia have greater access to substance abuse treatment services [45], inpatient and intensive case management to facilitate recovery, and immediate access to primary care in the same facility. As one of the largest single providers of mental health care in the U.S., the VA has also been at the forefront in implementing mental health parity, notably through the Mental Health Strategic Plan and the Uniform Mental Health Services Handbook. We speculate that lower unadjusted prevalence rates for cancer and suicide most likely reflect significant efforts to enact quality improvement efforts to target these risks for VA patients in general. Not only are older Veterans more likely to receive preventive screening for conditions like cancer than similar individuals outside the VA [46, 47], but patients who often do not receive preventive screenings in community settings due to conditions like obesity are actually more likely to be screening in the VA [48]. Finally, while quality improvement initiatives such as the implementation of a national electronic medical records system has radically improved care for all Veterans [24], efforts to improve coordination of care between specialty mental health and medical health providers is an ongoing process.

Present findings do not adjust for the prevalence of common psychiatric comorbidities that may raise CVD risk such as anxiety or depressive disorders. However, in a 9-year retrospective cohort study of 559,985 VA patients that examined the effects of mental health diagnoses on all-cause mortality, Chwastiak and colleagues [39] reported that only VA patients with schizophrenia and substance abuse disorders had an increased risk for all-cause mortality, even after adjustment for psychiatric and medical comorbidity, obesity, current smoking, and exercise frequency. While Chwastiak et al. did not address CVD mortality specifically, Kilbourne and colleagues [49] conducted a similar 8-year retrospective study of 147,193 VA patients with and without mental disorders, and found that VA patients with schizophrenia or other psychotic disorders, were more likely to die from heart disease-related mortality than Veterans diagnosed with depression or bipolar disorder, even after adjusting for sociodemographic factors, co-occurring diagnoses, and behavioral variables, including smoking and physical inactivity. These two studies offer support to the validity of the current study's findings despite limitations raised by analyses unadjusted for covariates. Subsequent studies will report the influence of important confounding variables including, exposure to specific psychiatric medications suggested to affect the onset and progression of CVD (e.g., antipsychotic medications).

Our finding of a mortality gap much smaller than that reported by other studies may also result from our choice of matched Veterans as our comparison population. We believe the relative homogeneity of U.S. Veterans making up both our schizophrenia and non-SMI groups, permits us to isolate more than other researchers to date, the impact of schizophrenia on mortality, at least for schizophrenia patients similar to our cohort. Other explanations for the small mortality gap we observed include possible selection effects. VA SMI patients are often diagnosed after enlistment and during military service, and may have had higher premorbid functioning compared to the general U.S. population with schizophrenia prior to their first psychotic episode. Additionally, early diagnosis and access to appropriate and continuous mental health care may help to mitigate the pathophysiological effects of psychosis on disease risk factors and help to identify common and avoidable medical conditions that can contribute to premature mortality if untreated (e.g., infectious disease, lung disease).

Perhaps most importantly, we note morbidity and mortality among Veterans with and without schizophrenia did not improved appreciably in the 8 years studied. This suggests, like the general U.S. population additional efforts are needed to improve the health of Veterans.

Limitations

Observational studies based on computerized administrative data have well-understood limitations that include unmeasured confounding factors. However, by matching schizophrenia Veterans with non-SMI Veterans, we believe we address major unmeasured confounders. We did not have a sufficient sample size or accurate measure to permit matching on race/ethnicity, but given the lower life expectancy of racial minorities in the U.S, we expect matching on race would result in even smaller difference across our study group. We also lack data on important cardiometabolic risk factors including: education, physical activity, diet, and environment. By intention, we did not adjust our analyses for comorbidities because our aim was to describe the relative health experiences of the two populations matched on age, gender, geography and visit timing. We expect such adjustment would move our observations closer to the null.

We relied on ICD-9 diagnosis codes from VA administrative data to identify patients' psychiatric and medical diagnoses, our measures depend on the accuracy and completeness of the codes recorded. Such data frequently underestimate the prevalence of psychiatric morbidity which affected both groups in this study [33]. Similarly, the prevalence of smoking is likely underestimated because VA providers often do not report this ubiquitous behavior with a formal diagnostic code. We additionally rely on the NDI Plus data for mortality statistics and cause of death; these data may lack sufficient sensitivity to accurately identify the primary cause of death [50, 51]. Finally, we were limited to an eight-year observation because VA pharmacy data used to confirm inclusion in both cohorts only became linked to the National Psychosis Registry starting in FY 2000. Future reports will explore differential effects of treatment with specific classes of psychotrophic drugs on morbidity and mortality outcomes, adjusting for key confounding variables such as demographic and comorbid health conditions.

Conclusions

This study described and compared the prevalence of cardiometabolic morbidity and mortality in a matched cohort of VA patients with and without schizophrenia diagnoses and found that while the burden of cardiometabolic disease continues to increase in all Veterans, schizophrenia does not appear associated with substantially higher differences in these diseases. Observed differences in mortality of patients with and without schizophrenia are significantly lower than reported in the literature and do not appear to have widened over this time period. We note that atherosclerotic disease stands out as the single greatest cause of the mortality gap we observed. Future research should further assess the modifiable causes of this excess atherosclerotic mortality and interventions and care models specific to these patients should be developed to address this. Exploration of such causes should include, in addition to behavioral factors, the potential contribution of cardiometabolically offensive psychotropic medications, especially second generation antipsychotics.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the VA Ann Arbor HSR&D Center for Clinical Management Research, the VA National Serious Mental Illness Treatment Resource and Evaluation Center, and the Health Services Research and Development Program within the Veterans Health Administration, Department of Veterans Affairs (IIR 08-116). The funders had no role in the design conduct or manuscript preparation for this study. Views expressed are those of the authors and not the Veterans Administration.

Appendices

Appendix Table 1.

Annual Prevalence of Cardiometabolic Diseases among Veterans Diagnosed with Schizophrenia and Matched Veterans without Serious Mental Illness Diagnosis, 2000 through 2007. N = 130,724 (62,362 from each group)

| 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | ||

| Diabetes | Schizophrenia | 17.9* | 19.6* | 21.1* | 22.5* | 23.5 | 24.9* | 25.9 | 26.8 |

| Non-SMI | 15.9 | 16.7 | 18.5 | 21.1 | 23.1 | 24.1 | 25.7 | 26.5 | |

| Coronary Artery Disease | Schizophrenia | 17.2* | 19.0* | 20.1* | 20.9* | 21.6* | 22.1* | 22.3* | 22.5* |

| Non-SMI | 19.6 | 20.7 | 22.2 | 24.6 | 26.2 | 26.2 | 27.3 | 27.1 | |

| Hypertension | Schizophrenia | 42.8* | 46.7* | 49.7 | 52.8* | 55.4* | 58.0* | 59.9* | 61.6* |

| Non-SMI | 40.6 | 45.0 | 49.6 | 55.4 | 59.61 | 60.8 | 63.6 | 64.3 | |

| Dyslipidemia | Schizophrenia | 25.2* | 29.9* | 35.1* | 40.0* | 45.0* | 49.9* | 53.2* | 55.9* |

| Non-SMI | 26.9 | 33.1 | 39.0 | 46.2 | 52.1 | 55.6 | 59.7 | 61.7 | |

| Obesity | Schizophrenia | 34.9 | 35.6 | 37.4 | 38.6 | 39.3 | 40.6 | 41.1 | 41.9 |

| Non-SMI | 35.6 | 36.1 | 37.4 | 38.9 | 39.7 | 40.7 | 41.7 | 42.4 | |

| No medical Cardio-metabolic morbidities | Schizophrenia | 37.0* | 33.4* | 30.4* | 27.3* | 24.7* | 22.1* | 20.5* | 19.6* |

| Non-SMI | 38.3 | 35.3 | 31.3 | 26.0 | 22.0 | 20.7 | 18.9 | 18.4 |

Chi-squared tests assessed significance of difference across the groups.

p<0.05.

Non-SMI group is matched on age, gender, parent Veterans Administration medical center and visit date. Non-SMI comparison group has no diagnosis of psychotic disorder. Annual prevalence based on ICD-9 diagnoses and disease-specific pharmacotherapy, once diagnosed patients with chronic conditions are assumed to continue with that condition until death or censorship. Obesity is defined as Body Mass Index ≥30 kg/m2. Annual prevalence of obesity is based on annual body mass index measures. Patients obese in one year are not assumed obese in subsequent years.

Appendix Table 2.

Annual Mortality Rate (per 10,000) by Fiscal Year Among Veterans Diagnosed with Schizophrenia and Matched Veterans without Serious Mental Illness Diagnosis

| 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rate | N | Rate | N | Rate | N | Rate | N | Rate | N | Rate | N | Rate | N | Rate | N | ||

| All Cause | Schizophrenia | 257* | 477 | 331* | 893 | 315* | 986 | 313* | 1129 | 330* | 1299 | 328* | 1328 | 309* | 1317 | 311* | 1369 |

| Non-SMI | 196 | 213 | 243 | 592 | 264 | 880 | 276 | 967 | 285 | 1041 | 274 | 1131 | 279 | 1169 | 247 | 1127 | |

| Atherosclerosis/HTN | Schizophrenia | 81 | 150 | 105* | 282 | 110* | 344 | 99 | 358 | 106 | 415 | 101* | 409 | 109* | 463 | 103* | 451 |

| Non-SMI | 64 | 69 | 78 | 189 | 90 | 300 | 94 | 329 | 96 | 352 | 86 | 356 | 89 | 372 | 84 | 384 | |

| Suicide | Schizophrenia | 8 | 14 | 10 | 27 | 8 | 24 | 12 | 42 | 11* | 45 | 13* | 54 | 6 | 27 | 7* | 30 |

| Non-SMI | 5 | 5 | 7 | 18 | 7 | 25 | 8 | 29 | 5 | 17 | 5 | 21 | 5 | 23 | 4 | 16 | |

| Trauma/accident | Schizophrenia | 15 | 27 | 19* | 50 | 19 | 60 | 23* | 83 | 19 | 73 | 22 | 91 | 23* | 96 | 26* | 114 |

| Non-SMI | 13 | 14 | 12 | 28 | 15 | 49 | 16 | 57 | 15 | 53 | 19 | 79 | 16 | 65 | 13 | 59 | |

| Malignancy | Schizophrenia | 56 | 104 | 77 | 207 | 56 | 176 | 65 | 235 | 67 | 265 | 71 | 287 | 60 | 257 | 62 | 271 |

| Non-SMI | 58 | 63 | 74 | 180 | 58 | 193 | 62 | 218 | 70 | 255 | 66 | 271 | 65 | 271 | 59 | 269 | |

| Pulmonary Disease | Schizophrenia | 19* | 36 | 23* | 63 | 31* | 98 | 22 | 79 | 23 | 90 | 23 | 95 | 18 | 75 | 23 | 101 |

| Non-SMI | 8 | 9 | 12 | 28 | 20 | 67 | 20 | 70 | 18 | 64 | 18 | 73 | 19 | 81 | 20 | 90 | |

| Other causes | Schizophrenia | 80* | 146 | 100* | 264 | 93* | 284 | 94* | 332 | 107* | 411 | 99* | 392 | 96 | 399 | 93* | 402 |

| Non-SMI | 50 | 53 | 62 | 149 | 75 | 246 | 77 | 264 | 84 | 300 | 82 | 331 | 87 | 357 | 69 | 309 | |

Chi-squared tests assessed significance of difference across the groups. Death rate is calculated as number of deaths per 10,000 person years. SMI= serious mental illness. Patients in the non-SMI group are matched with the schizophrenia patients on age, gender, parent medical center and visit date; they have no diagnosis of psychotic illness. Cause of death as categorized by the National Death Index Plus data. Deaths attributed to “atherosclerotic/HTN” are those categorized in this data set as death due to: atherosclerosis hypertension, coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular disease, and aortic aneurysm.

p<0.05

Appendix Table 3.

Years of Potential Life Lost Patients with Schizophrenia and Matched Comparison Population with No Serious Mental Illness, by Year Mean(SD)

| 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Schizophrenia | 12.8 (10) | 13.2 (10) | 13.8 (10.1) | 14.4 (10.1) | 15.0 (10.0) | 14.8 (10.0) | 15.3 (10.0) | 15.4 (9.8) |

| Non-SMI | 11.8 (9.6) | 12.5 (9.3) | 13.3 (9.3) | 13.5 (9.3) | 13.8 (9.5) | 13.6 (9.5) | 13.9 (9.6) | 14.0 (9.5) |

| P Value | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

Statistical test of difference of YPLL between the two cohorts: t-test was used

Appendix Table 4.

Psychiatric and Neurocognitive ICD-9 Codes

| Schizophrenia | 295.0 – 295.9 schizophrenia disorders |

| Exclusion Criteria | |

|

| |

| Dementia | 290.0 Senile dementia uncomplicated |

| 290.1 Presenile dementia uncomplicated | |

| 290.11 Presenile dementia with delirium | |

| 290.12 Presenile dementia with delusional features | |

| 290.13 Presenile dementia with depressive features | |

| 290.20 Senile dementia with delusional features | |

| 290.21 Senile dementia with depressive features | |

| 290.30 Senile dementia with delirium | |

| 290.40 Vascular dementia uncomplicated | |

| 290.41 Vascular dementia with delirium | |

| 290.42 Vascular dementia with delusions | |

| 290.43 Vascular dementia with depressed mood | |

| 290.8 Other specified senile psychotic conditions | |

| 290.9 Unspecified senile psychotic condition | |

| 291.2 Alcohol-induced persisting dementia | |

| 294.0 Amnestic disorder CCEa | |

| 294.1 Dementia in CCEa | |

| 294.10 Dementia CCE without behavioral disturbancea | |

| 294.11 Dementia CCE w/ behavioral disturbancesa | |

| 294.8 Other persistent mental disorder due CCEa | |

| 294.9 Unspecified persistent mental disorder due to CCEa | |

| 331.0 Alzheimers disease | |

| 331.2 Senile degeneration of brain | |

| 333.4 Huntington's chorea | |

| 331.19 Other frontotemporal dementia | |

| 331.82 Dementia with Lewy bodies | |

| 331.11 Pick's disease | |

| 797.0 Senility without mention of psychosis | |

CCE = Conditions classified elsewhere

Appendix Table 5.

Cardiometabolic Disease ICD-9 Diagnosis Codes

| Included Diagnoses | ICD-9 codes |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Diabetes mellitus type 2 | 250.xx Diabetes mellitus (except 250.1 – with ketoacidosis) |

|

| |

| Coronary artery disease | 411 Other acute and subacute forms of ischemic heart disease |

| 413 Angina pectoris | |

| 414 Other forms of chronic ischemic heart disease | |

|

| |

| Hyperlipidemia | 272.0 Pure hypercholesterolemia |

| 272.1 Pure hyperglyceridemia | |

| 272.2 Mixed hyperlipidemia | |

| 272.3 Hyperchylomicronemia, other and unspecified | |

| 272.4 Hyperlipidemia | |

|

| |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 410 AMI inpatient diagnosis only |

|

| |

| Obesity | 278.00 Obesity |

| 278.01 Morbid obesity | |

| 783.1 Abnormal weight gain | |

|

| |

| Hypertension | 401 Essential hypertension |

|

| |

| Cerebrovascular accident (Inpatient diagnosis only) | 431 Intracerebral hemorrhage |

| 434.01 Cerebral thrombosis with cerebral infarction | |

| 434.11 Cerebral embolism with cerebral infarction | |

| 434.91 Cerebral artery occlusion unspecified with cerebral infarction | |

Appendix Table 6.

Prescription Drug Classes Used to Identify Disease Prevalence and Morbidity

| Disease | VA Medication Code | Prescription Classification |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Diabetes | ||

| HS500 | Blood glucose regulation agents | |

| HS501 | Insulin | |

| HS502 | Oral hypoglycemic agents | |

| HS503 | Anti-hypoglycemics | |

|

| ||

| Coronary Artery Disease/Arrythmia (Heart disease) | ||

| CV050 | Digitalis glycosides | |

| CV250 | Antianginals | |

| CV300 | Antiarrhthmics | |

| CV900 | Other cardiovascular agents | |

|

| ||

| Hyperlipidmia | ||

| CV350 | ||

|

| ||

| Hypertension | ||

| CV701 | Thiazides - related diuretics | |

| CV150 | Alpha blockers | |

|

| ||

| Coronary Artery Disease and/or Hypertension | ||

| CV100 | Beta blocker | |

| CV200 | Calcium channel blockers | |

| CV400 | Antihypertensive combinations | |

| CV490 | Other antihypertensives | |

| CV500 | Peripheral vasodilatorsa | |

| CV703 | Carbonic anhydrase inhibitor diuretics | |

| CV800 | Ace inhibitors (no diabetes mellitus) | |

| CV805 | Angiotensin II inhibitor (no diabetes mellitus) | |

| Cv806 | Direct rennin inhibitora | |

No prescriptions for this class found in VA formulary

Appendix Table 7.

Psychiatric Comorbidity Codes

| Included Diagnoses | ICD-9 codes |

|---|---|

| Anxiety disorders | |

| 300.00 Anxiety disorder unspecified | |

| 300.01 Panic disorder without agoraphobia | |

| 300.02 Generalized anxiety disorder | |

| 300.09 Other anxiety disorders | |

| 300.10 Dissociative, conversion and factitious disorders | |

| 300.20 Phobia unspecified | |

| 300.21 Agoraphobia with panic attacks | |

| 300.22 Agoraphobia without panic attacks | |

| 300.23 Social phobia | |

| 300.29 Other isolated or specific phobias | |

| Post traumatic stress disorder | |

| 309.81 Posttraumatic stress disorder | |

| Bipolar Disorders | |

| 296.0 Bipolar I, single manic episode | |

| 296.1 Manic disorder recurrent episode | |

| 296.4 Bipolar I disorder, most recent episode manic | |

| 296.5 Bipolar I disorder, most recent episode depressed | |

| 269.6 Bipolar I disorder, most recent episode mixed | |

| 269.7 Bipolar I disorder most recent episode unspecified | |

| 296.8 Other and unspecified bipolar disorders | |

| Depression | |

| 293.83 Mood disorder in conditions classified elsewhere | |

| 296.2 Major depressive disorder single episode | |

| 296.3 Major depressive disorder recurrent episode | |

| 296.9 Unspecified episodic mood disorder | |

| 296.99 Other specified episodic mood disorder | |

| 298.0 Depressive type psychosis | |

| 300.4 Dysthymic disorder | |

| 301.12 Chronic depressive personality disorder | |

| 309.0 Adjustment disorder with depressed mood | |

| 309.1 Adjustment reaction with prolonged depressive reaction | |

| 311.0 Depressive disorder not elsewhere classified | |

| Substance abuse disorder | 303.0 Acute alcoholic intoxication |

| 291 Alcohol withdrawal delirium | |

| 292 Drug-induced mental disorders | |

| 303.9 Other and unspecified alcohol dependence | |

| 304.1 Sedative, hypnotic or anxiolytic dependence | |

| 304.4 Amphetamine and other psychostimulant dependence | |

| 304.5 Hallucinogen dependence | |

| 304.6 Other specified drug dependence | |

| 304.8 Combinations of drug dependence excluding opioid type drug | |

| 304.9 Unspecified drug dependence | |

| 305.0 Nondependent alcohol abuse | |

| 305.2 Nondependent cannibus abuse | |

| 305.3 Nondependent hallucinogen abuse | |

| 305.4 Nondependent sedative, hypnotic, or anxiolytic abuse | |

| 305.5 Nondependent opioid abuse | |

| 305.6 Nondependent cocaine abuse | |

| 305.7 Nondependent amphetamine/acting sympathommetic abuse | |

| 305.8 Nondependent antidepressant type abuse | |

| 305.9 Nondependent other mixed or unspecified drug abuse | |

| Tobacco Exposure Measure (tobacco related disease or diagnosis of tobacco use) | Chronic Non-Asthmatic Lung Disease: ICD-9 Dx code: 415.0, 416.8, 416.9, 491.0, 492.0, 494.0, 496.0 |

| Tobacco use: ICD-9 305.1, V15.82, 989.84 tobacco | |

| 649.0 Tobacco use disorder complicating pregnancy, childbirth, puerperium |

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

All authors fulfill authorship requirements. Authors Lai, McCarthy, Austin, Welsh and Kilbourne had full access to the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

This work has not been previously published in any form.

References

- 1.Colton CW, Manderscheid RW. Congruencies in increased mortality rates, years of potential life lost, and causes of death among public mental health clients in eight states. Prev Chronic Dis. 2006;3:A42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bushe CJ, Taylor M, Haukka J. Mortality in schizophrenia: a measurable clinical endpoint. J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24:17–25. doi: 10.1177/1359786810382468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saha S, Chant D, McGrath J. A systematic review of mortality in schizophrenia: is the differential mortality gap worsening over time? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:1123–1131. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.10.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bouza C, Lopez-Cuadrado T, Amate JM. Physical disease in schizophrenia: A population-based analysis in Spain. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:745. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Curkendall SM, Mo J, Glasser DB, Rose Stang M, Jones JK. Cardiovascular disease in patients with schizophrenia in Saskatchewan, Canada. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65:715–720. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen YH, Lee HC, Lin HC. Mortality among psychiatric patients in Taiwan--results from a universal National Health Insurance programme. Psychiatry Res. 2010;178:160–165. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2008.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fors BM, Isacson D, Bingefors K, Widerlov B. Mortality among persons with schizophrenia in Sweden: an epidemiological study. Nord J Psychiatry. 2007;61:252–259. doi: 10.1080/08039480701414932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown S, Inskip H, Barraclough B. Causes of the excess mortality of schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;177:212–217. doi: 10.1192/bjp.177.3.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bushe CJ, Hodgson R. Schizophrenia and cancer: in 2010 do we understand the connection? Can J Psychiatry. 2010;55:761–767. doi: 10.1177/070674371005501203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aragon TJ, Lichtensztajn DY, Katcher BS, Reiter R, Katz MH. Calculating expected years of life lost for assessing local ethnic disparities in causes of premature death. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:116. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu J, Kochanek KD, Murphy SL, Tejada-Vera B. National vital statistic reports. vol. 58. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: 2010. Deaths: Final data for 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McEvoy JP, Meyer JM, Goff DC, Nasrallah HA, Davis SM, Sullivan L, Meltzer HY, Hsiao J, Scott Stroup T, Lieberman JA. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia: baseline results from the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) schizophrenia trial and comparison with national estimates from NHANES III. Schizophr Res. 2005;80:19–32. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Osborn DP, Levy G, Nazareth I, Petersen I, Islam A, King MB. Relative risk of cardiovascular and cancer mortality in people with severe mental illness from the United Kingdom's General Practice Rsearch Database. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:242–249. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.2.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Copeland LA, Zeber JE, Rosenheck RA, Miller AL. Unforeseen inpatient mortality among veterans with schizophrenia. Med Care. 2006;44:110–116. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000196973.99080.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laursen TM, Nordentoft M. Heart disease treatment and mortality in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder - changes in the Danish population between 1994 and 2006. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45:29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown S, Kim M, Mitchell C, Inskip H. Twenty-five year mortality of a community cohort with schizophrenia. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196:116–121. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.109.067512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Capasso RM, Lineberry TW, Bostwick JM, Decker PA, St Sauver J. Mortality in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder: an Olmsted County, Minnesota cohort: 1950–2005. Schizophr Res. 2008;98:287–294. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tiihonen J, Lonnqvist J, Wahlbeck K, Klaukka T, Niskanen L, Tanskanen A, Haukka J. 11-year follow-up of mortality in patients with schizophrenia: a population-based cohort study (FIN11 study) Lancet. 2009;374:620–627. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60742-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. [ http://www.census.gov/]

- 20.Narrow WE, Regier DA, Norquist G, Rae DS, Kennedy C, Arons B. Mental health service use by Americans with severe mental illnesses. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2000;35:147–155. doi: 10.1007/s001270050197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. SAMHSA 10 × 10 Wellness Campaign [ http://www.promoteacceptance.samhsa.gov/10by10/]

- 22.Druss BG, Bornemann TH. Improving health and health care for persons with serious mental illness: the window for US federal policy change. JAMA. 2010;303:1972–1973. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brown S. Excess mortality of schizophrenia. A meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;171:502–508. doi: 10.1192/bjp.171.6.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kizer KW, Dudley RA. Extreme makeover: Transformation of the Veterans Health Care system. Annu Rev Public Health. 2009;30:313–339. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.29.020907.090940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Post EP, Metzger M, Dumas P, Lehmann L. Integrating mental health into primary care within the Veterans Health Administration. Fam Syst Health. 2010;28:83–90. doi: 10.1037/a0020130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Blow FC, McCarthy JF, Valenstein M, Visnic S, Welsh D, Mach J. Care for Veterans with Psychosis in the Veterans Health Administration, FY09: 11th Annual National Psychosis Registry Report. Serious Mental Illness Treatment Resource and Evaluation Center; Ann Arbor, MI: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCarthy JF, Valenstein M, Kim HM, Ilgen M, Zivin K, Blow FC. Suicide mortality among patients receiving care in the veterans health administration health system. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169:1033–1038. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Doody MM, Hayes HM, Bilgrad R. Comparability of national death index plus and standard procedures for determining causes of death in epidemiologic studies. Ann Epidemiol. 2001;11:46–50. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00177-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Life Tables. [ http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/life_tables.htm]

- 30.Lloyd-Jones D, Adams R, Carnethon M, De Simone G, Ferguson TB, Flegal K, Ford E, Furie K, Go A, Greenlund K, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2009 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2009;119:480–486. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.191259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Data Warehouse on trends in health and aging. [ http://www.cdc.govnchs/agingact.htm]

- 32.Redelmeier DA, Tan SH, Booth GL. The treatment of unrelated disorders in patients with chronic medical diseases. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1516–1520. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199805213382106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Druss BG, Rosenheck RA, Desai MM, Perlin JB. Quality of preventive medical care for patients with mental disorders. Med Care. 2002;40:129–136. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200202000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krein SL, Bingham CR, McCarthy JF, Mitchinson A, Payes J, Valenstein M. Diabetes treatment among VA patients with comorbid serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57:1016–1021. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.7.1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cowie CC, Rust KF, Ford ES, Eberhardt MS, Byrd-Holt DD, Li C, Williams DE, Gregg EW, Bainbridge KE, Saydah SH, et al. Full accounting of diabetes and pre-diabetes in the U.S. population in 1988–1994 and 2005–2006. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:287–294. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2008. JAMA. 2010;303:235–241. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kahwati LC, Lance TX, Jones KR, Kinsinger L. RE-AIM evaluation of the Veterans Health Administration's MOVE! Weight Management Program. Translational Behavioral Medicine. 2011;1:551–560. doi: 10.1007/s13142-011-0077-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kilbourne AM, Ignacio RV, Kim HM, Blow FC. Datapoints: are VA patients with serious mental illness dying younger? Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60:589. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.5.589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chwastiak LA, Rosenheck RA, Desai R, Kazis LE. Association of psychiatric illness and all-cause mortality in the National Department of Veterans Affairs Health Care System. Psychosom Med. 2010;72:817–822. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181eb33e9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tran E, Rouillon F, Loze JY, Casadebaig F, Philippe A, Vitry F, Limosin F. Cancer mortality in patients with schizophrenia: an 11-year prospective cohort study. Cancer. 2009;115:3555–3562. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Piatt EE, Munetz MR, Ritter C. An examination of premature mortality among decedents with serious mental illness and those in the general population. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61:663–668. doi: 10.1176/ps.2010.61.7.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bouza C, Lopez-Cuadrado T, Amate JM. Hospital admissions due to physical disease in people with schizophrenia: a national population-based study. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2010;32:156–163. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Druss BG, Zhao L, Von Esenwein S, Morrato EH, Marcus SC. Understanding excess mortality in persons with mental illness: 17-year follow up of a nationally representative US survey. Med Care. 2011;49:599–604. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31820bf86e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Druss BG, Rohrbaugh RM, Levinson CM, Rosenheck RA. Integrated medical care for patients with serious psychiatric illness: a randomized trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:861–868. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.9.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kilbourne AM, Salloum I, Dausey D, Cornelius JR, Conigliaro J, Xu X, Pincus HA. Quality of care for substance use disorders in patients with serious mental illness. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2006;30:73–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Trivedi AN, Grebla RC. Quality and equity of care in the veterans affairs health-care system and in medicare advantage health plans. Med Care. 2011;49:560–568. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31820fb0f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chao HH, Schwartz AR, Hersh J, Hunnibell L, Jackson GL, Provenzale DT, Schlosser J, Stapleton LM, Zullig LL, Rose MG. Improving colorectal cancer screening and care in the Veterans Affairs Healthcare system. Clinical colorectal cancer. 2009;8:22–28. doi: 10.3816/CCC.2009.n.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yancy WS, Jr., McDuffie JR, Stechuchak KM, Olsen MK, Oddone EZ, Kinsinger LS, Datta SK, Fisher DA, Krause KM, Ostbye T. Obesity and receipt of clinical preventive services in veterans. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18:1827–1835. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kilbourne AM, Morden NE, Austin K, Ilgen M, McCarthy JF, Dalack G, Blow FC. Excess heart-disease-related mortality in a national study of patients with mental disorders: identifying modifiable risk factors. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2009;31:555–563. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Saydah SH, Geiss LS, Tierney E, Benjamin SM, Engelgau M, Brancati F. Review of the performance of methods to identify diabetes cases among vital statistics, administrative, and survey data. Ann Epidemiol. 2004;14:507–516. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2003.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smith Sehdev AE, Hutchins GM. Problems with proper completion and accuracy of the cause-of-death statement. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:277–284. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.2.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]