Abstract

Objective

Physical symptoms are common and a leading reason for primary care visits, however data are lacking on their prevalence among racial/ethnic minorities in the United States. This study aimed to compare the prevalence of physical symptoms among White, Latino, and Asian Americans, and examine the association of symptoms and acculturation.

Methods

We analyzed data from the National Latino and Asian American Study, a nationally-representative survey of 4864 White, Latino, and Asian Americans adults. We compared the age- and gender-adjusted prevalence of fourteen physical symptoms among the racial/ethnic groups and estimated the association between indicators of acculturation (English proficiency, nativity, generational status, and proportion of lifetime in the United States) and symptoms among Latino and Asian Americans.

Results

After adjusting for age and gender, the mean number of symptoms was similar for Whites (1.00) and Latinos (0.95) but significantly lower among Asian-Americans (0.60, p < 0.01 versus Whites). Similar percentages of Whites (15.4%) and Latinos (13.0%) reported 3 or more symptoms, whereas significantly fewer Asian-Americans (7.7%, p<0.05 versus Whites) did. In models adjusted for sociodemographic variables and clinical status (psychological distress, medical conditions, and disability), acculturation was significantly associated with physical symptoms among both Latino and Asian Americans, such that the most acculturated individuals had the most physical symptoms.

Conclusions

The prevalence of physical symptoms differs across racial/ethnic groups, with Asian Americans reporting fewer symptoms than Whites. Consistent with a ‘healthy immigrant’ effect, increased acculturation was strongly associated with greater symptom burden among both Latino and Asian Americans.

MeSH Key Words: Acculturation, Asian Americans, Epidemiology, Hispanic Americans, Signs and Symptoms

Introduction

General physical symptoms are prevalent in the community and are associated with functional impairment, psychopathology, and health service use.[1–5] Although many believe that physical symptoms vary across cultures, the data suggesting associations between race/ethnicity, acculturation, and physical symptoms are inconsistent. Some have suggested that physical symptoms themselves or their presentation as an expression of distress are especially common among racial/ethnic minorities [6–12] and that the process of acculturation may shape the expression of physical symptoms among racial/ethnic minorities in the United States.[13] In contrast, there is evidence that physical symptoms are common across countries and cultures, [3, 14] evidence of considerable cross-cultural overlap in idiopathic or unexplained physical symptoms,[15] and studies indicating that physical symptoms are more common among non-Latino white Americans than certain racial/ethnic minorities.[2, 5]

Because physical symptoms are the most common reason for primary care visits, are a common clinical presentation of mental disorders, and are associated with disproportionate use of general medical rather than mental health services for mental health care,[1, 2, 14, 16] it is important to understand how race/ethnicity and acculturation are associated with physical symptoms in the general population. Prior epidemiological data on lifetime physical symptoms in the community derives from the Epidemiological Catchment Area (ECA) studies of the early 1980’s, [17] which revealed mixed results on how lifetime physical symptoms are associated with race/ethnicity. Findings from the Los Angeles ECA study revealed a higher prevalence of physical symptoms among Latina women compared to white women, but this pattern was not evident among men. [6] Compared to whites and Mexican Americans in the ECA sample, island Puerto Ricans in a parallel survey had higher rates of somatization disorder and abridged somatization.[8] In contrast, in Los Angeles, Latinos, African-Americans, and Asian-Americans were significantly less likely than whites to meet criteria for somatization disorder. [18] Across respondents from four communities in the study, there were few differences in lifetime physical symptom prevalence by race, although most symptoms were slightly more common among whites compared to non-white respondents.[2] Among the full ECA sample, after adjustment for sociodemographic variables, compared to whites, significantly more African Americans but fewer Asian Americans met full criteria for somatization disorder, whereas rates did not differ among Latinos and whites.[18] Although the authors of the latter report conclude the assumption that somatization is more common among Latino and Asian Americans may be erroneous [18], nevertheless, the notion that somatization is particularly common among racial/ethnic minority groups was embedded into the highly influential Surgeon General’s report and the subsequent Supplement on culture, race, and ethnicity. [19, 20] Physical symptoms were not included in recent epidemiological surveys such as the National Comorbidity Survey, the National Comorbidity Survey replication, or the National Survey of American Life. Consequently, the National Latino and Asian American Survey (NLAAS) is the only nationally representative survey with data on the prevalence of physical symptoms in the United States.

The present study reports the prevalence of physical symptoms and their association with race/ethnicity and acculturation among the NLAAS sample, a nationally representative community-based sample of non-Latino white, Latino, and Asian Americans. This research tests the following two hypotheses: (1) Latino and Asian Americans experience more physical symptoms than non-Latino white Americans; and (2) less acculturated Latino and Asian Americans experience more physical symptoms than their more acculturated counterparts.

Methods

Participants

This study analyzed data from the National Latino and Asian American Survey (NLAAS), part of the NIMH Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Studies.[21] Participants were a nationally-representative sample of non-institutionalized adults (age 18 or older) living in one of the 50 states or the District of Columbia. The final NLAAS sample consisted of 2554 Latino Americans (Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, and “other”), 2095 Asian Americans (Chinese, Vietnamese, Filipino, and “other”) and 215 non-Latino whites. Classification of ethnic subgroups was based on participant self-report using the same question as the United States census. A detailed description of the sampling strategies, weighting, and study design have been reported previously. [21, 22] Trained bilingual interviewers conducted computer-assisted interviews in-person or by telephone in 2002–2003 in one of the following languages: English, Spanish, Mandarin, Vietnamese, or Tagalog. As reported elsewhere, the weighted sample was similar to the 2000 United States census population in age, gender, education, marital status, and geographic distribution, but differed from the census population because the sample included more immigrants and more low-income participants. [22] Weighted response rates were 75.5% for Latinos and 65.6% for Asian Americans.

Measures

Acculturation

A multidimensional approach to measurement of acculturation was implemented using proxy measures such as English proficiency, nativity, parental nativity, and years in the United States that have been used successfully in prior research. [23, 24] English language proficiency was determined according to participants’ responses to the question “How well do you speak English?” and coded dichotomously as “poor/fair” or “good/excellent”. [25–27] Respondents reported their own and their parents’ place of birth as within or outside the United States. Puerto Ricans who were not born in one of the fifty US states were considered foreign-born. Foreign-born participants reported their age at immigration. The proportion of the immigrant’s life spent in the United States was calculated as the number of years in the United States divided by the participant’s age. Nativity, parental nativity, and proportion of lifetime spent in the United States were combined to create a single aggregate variable with the following six categories: Immigrant, 0–25% lifespan in the US; Immigrant, 25–50% lifespan in US; Immigrant, 50–100% lifespan in US; US-born, 2 foreign-born parents; US-born, 1 foreign-born parent; US-born, 2 parents US-born.

Physical Symptoms

The NLAAS included a module of physical symptoms that was not included in other surveys of the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Studies. Fourteen symptoms were selected based upon prior studies of physical symptoms in the community and among racial/ethnic minority populations [1, 5] indicating that these symptoms are common and disabling, and associated with psychopathology: dizziness; fainting spells; trouble swallowing or lump in throat; nausea, gas, indigestion; stomach or belly pain; diarrhea or constipation; chest pain; heart pounding or racing; shortness of breath or trouble breathing; pain in arms, legs, joints; back pain; pains or problems related to menstruation; pain or problems during sex; and numbness or tingling. To exclude symptoms that were transient or minor, a symptom was counted as present if participants reported that it was “frequent or severe” such that they had discussed the symptom with a healthcare professional within the past 12 months. Because the requirement for discussion with a professional may reflect help-seeking behavior rather than severity, sensitivity analyses were conducted using lifetime symptoms that did not require that they were discussed with a provider.

Covariates

Participants reported demographic information including age, gender, marital status (married/cohabitating, divorced/separated/widowed, never married), education (≤ 11 years, 12 years, 13–15 years, ≥16 years), employment status (employed, unemployed, or out of labor force), and income (≤ $14,999, $15,000 to $34,999, $35,000 to $74,999, ≥ $75,000). The presence of chronic medical conditions (arthritis or rheumatism, gastrointestinal ulcer, hypertension, myocardial infarction, stroke, diabetes, cancer, asthma, COPD or chronic lung disease, tuberculosis, or HIV/AIDS) was also determined. The Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K-10) assessed symptoms of psychological distress over the last 30 days. Scores on this instrument are strongly associated with the likelihood of having anxiety and depressive disorders. [28, 29] Functional disability in the past 30-days was assessed with the World Health Organization disability assessment scale (WHO-DAS). [30] This instrument covers the domains of cognitive functioning, mobility, self-care, social functioning, and role functioning, and assesses the number of days in the past 30 days when these problems interfered with functioning.

Data Analysis

Sociodemographic variables and physical symptoms were compared among racial/ethnic groups using Rao-Scott chi-square tests, which adjust for the complex survey design. [31] Logistic regression models were constructed to assess the association between language proficiency, acculturation, and physical symptoms while controlling for additional sociodemographic variables and the following clinical variables that have previously been shown to be related to physical symptoms: psychological distress, disability and medical morbidity. For sensitivity analyses, we adjusted for healthcare access.

Results

Sociodemographic data

Table 1 reports the demographic characteristics for Latino, Asian, and non-Latino white participants adjusted for age and gender. Relative to non-Latino whites, more Latinos had low income, whereas both Latinos and Asians were more likely to be married or cohabitating, have lower education, to be foreign-born, with foreign-born parents, and to have lived a smaller proportion of their lives in the United States.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of White, Latino, and Asian Americans (Age- and Gender- Adjusted)

| Characteristic | White N = 215 |

Latino N = 2554 |

p (Latino vs White) |

Asian N = 2095 |

p (Asian vs. White) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marital Status | |||||

| Married/cohabitating | 60.1% | 64.5% | 70.8% | ||

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 16.0% | 20.1% | 0.05 | 10.2% | 0.04 |

| Never married | 23.9% | 15.4% | 19.0% | ||

| Education | |||||

| 11 years or less | 7.7% | 48.0% | 17.0% | ||

| 12 years | 19.3% | 22.1% | <0.001 | 17.9% | 0.03 |

| 13–15 years | 32.5% | 19.6% | 24.3% | ||

| 16 years or more | 40.4% | 10.4% | 40.8% | ||

| Household Income | |||||

| $0–$14,999 | 14.2% | 29.4% | 19.3% | ||

| $15,000–$34,999 | 11.1% | 27.8% | <0.001 | 13.5% | 0.25 |

| $35,000–$74,999 | 22.7% | 27.3% | 28.3% | ||

| $75,000+ | 52.0% | 15.4% | 38.9% | ||

| Employment | |||||

| Employed | 67.8% | 57.7% | 61.4% | ||

| Unemployment | 4.3% | 6.0% | 0.09 | 5.8% | 0.32 |

| Out of Labor Force | 28.0% | 36.4% | 32.8% | ||

| Acculturation Categories | |||||

| US-born, 2 US-born parents | 70.5% | 19.8% | 9.0% | ||

| US-born, 1 foreign-born parent | 13.8% | 6.9% | 4.8% | ||

| US-born, 2 foreign-born parents | 7.6% | 14.0% | <0.001 | 8.6% | <0.001 |

| Foreign-born, > 50% Life span in US | 3.9% | 27.9% | 24.4% | ||

| Foreign-born, 25–50% Life span in US | 2.0% | 18.5% | 26.8% | ||

| Foreign-born, < 25% Life span in US | 2.1% | 12.9% | 26.4% | ||

| Physical Symptoms | |||||

| Number (mean) | 1.00 | 0.95 | 0.69 | 0.60 | 0.005 |

| At least 1 physical symptom | 40.7% | 37.2% | 0.27 | 29.1% | <0.001 |

| At least 3 physical symptoms | 15.4% | 13.0% | 0.47 | 7.7% | 0.005 |

| Chronic Medical Conditions | |||||

| 0 | 52.0% | 54.0% | 56.2% | ||

| 1 | 26.2% | 23.3% | 0.69 | 26.3% | 0.42 |

| ≥2 | 21.8% | 22.8% | 17.5% | ||

| Psychological distress (K10 score, range 10–50) | 12.76 | 13.94 | <0.001 | 13.20 | 0.11 |

| Days out of role because of mental health problems (Range 0–30 days) | 0.26 | 0.31 | 0.77 | 0.12 | 0.36 |

| Cognitive Functioning Score (Range 0–100) | 0.68 | 0.81 | 0.57 | 0.65 | 0.91 |

| Mobility Score (Range 0–100) | 1.78 | 3.90 | 0.002 | 1.39 | 0.44 |

| Self-care Score (Range 0–100) | 0.65 | 1.05 | 0.37 | 0.42 | 0.55 |

| Social Functioning Score (Range 0–100) | 0.34 | 0.45 | 0.42 | 0.43 | 0.72 |

| Role Functioning Score (Range 0–100) | 7.41 | 9.42 | 0.14 | 6.11 | 0.31 |

Clinical data

After adjustment for age and gender, psychological distress was higher among Latinos than non-Latino whites (Table 1), but racial/ethnic groups did not differ in the prevalence of chronic medical conditions. Only one of the comparisons for functional disability was statistically significant, with Latinos reporting worse mobility than non-Latino whites.

Prevalence of Physical Symptoms

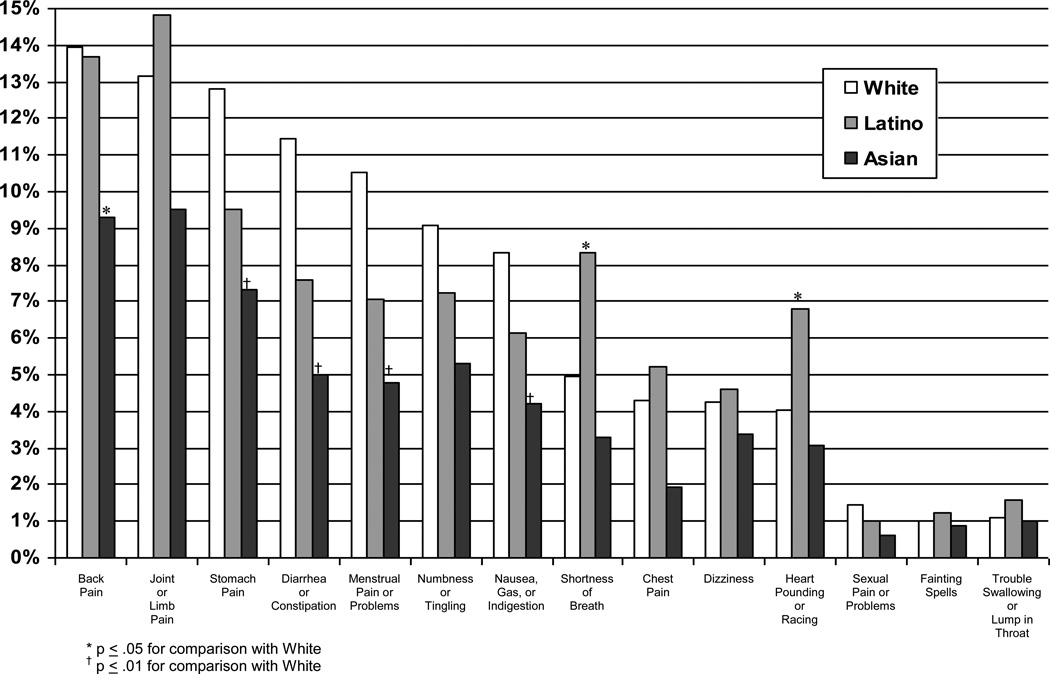

The overall number of physical symptoms reported by non-Latino whites and Latinos after adjustment for age and gender was comparable (white: 1.00; Latino: 0.95, p = 0.69), whereas Asian Americans reported significantly fewer physical symptoms than whites (Asian: 0.60, p < 0.01) (Table 1). This pattern was unchanged following adjustment for marital status, education, income, employment, psychological distress, disability, and chronic medical conditions. Likewise, significantly fewer Asians than whites reported a high symptom burden of 3 or more physical symptoms (white: 15.4%, Asian: 7.7%, p < 0.05), whereas Latinos and whites did not differ (Latino: 13.0%). Twelve of the fourteen individual symptoms were reported equally among Latinos and whites, whereas significantly more Latinos than whites reported shortness of breath (white: 4.9%; Latino 8.3%, p < 0.05) and palpitations (white: 4.0%; Latino: 6.8%, p < 0.05) (Figure 1 and Supplementary Table). In contrast, fewer Asians than whites endorsed five of the fourteen symptoms: back pain (white: 14.0%; Asian: 9.3%, p < 0.05); stomach pain (white: 12.8%; Asian 7.3%, p < 0.01); diarrhea or constipation (white: 11.5%; Asian: 5.0%, p < 0.05); menstrual pain (white: 10.5%; Asian: 4.8%, p < 0.01); and nausea, gas or indigestion (white: 8.3%; Asian 4.2%, p < 0.01). The sensitivity analyses using lifetime symptoms yielded the same results among Asians, but did reveal some differences among Latinos. Specifically, when lifetime symptom prevalence was adjusted only for age and gender, Latinos reported significantly more symptoms than Whites (1.55 versus 1.23, p < 0.05), although they were not significantly more likely than Whites to have any lifetime symptom (48.8% versus 45.3%, p=0.27) or 3 or more symptoms (22.8% versus 19.8%, p = 0.33). Additionally, following adjustment for sociodemographic and clinical characteristics, Latinos and Whites did not differ in the number of lifetime symptoms (Latino OR: 1.12, p=0.42).

Figure 1.

Prevalence of Physical Symptoms by Racial/Ethnic Group (Age- and Gender-Adjusted)

Association of Acculturation and Physical Symptoms

Multivariate analyses controlling for sociodemographic variables, psychological distress, chronic medical conditions, and disability demonstrated that greater acculturation was significantly and positively associated with the number of physical symptoms reported among both Latino and Asian Americans (Table 2). After adjusting for covariates, US-born individuals with 2 US-born parents reported the most physical symptoms. Among Latinos, the association follows a graded pattern with reducing risk associated with progressively lower levels of acculturation. After accounting for the aggregate indicator of acculturation, language proficiency did not add significantly to the model. To evaluate the possibility that health service use confounded the association between acculturation and physical symptoms, two sets of sensitivity analyses were conducted. First, we restricted the analyses to those individuals who had a primary care provider or used a general medical service within the past year. The results were unchanged with exception that the reduced risk for physical symptoms among the least acculturated Latinos was slightly attenuated (OR 0.64, p=0.065, data not shown). A second sensitivity analysis with lifetime symptoms produced the same results as the first sensitivity analyses, again with the reduced risk for physical symptoms attenuated among the least acculturated Latinos (OR 0.89, p=0.45).

Table 2.

Correlates of Physical Symptom Burden among Latino and Asian Americans

| Latino | Asian | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | p | OR | p | |

| Independent Variables | ||||

| Acculturation categories | ||||

| US-born, 2 US-born parents - reference | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| US-born, 1 foreign-born parent | 0.71 | 0.06 | 0.52 | 0.009 |

| US-born, 2 foreign-born parents | 0.64 | 0.03 | 0.56 | 0.03 |

| Foreign-born, > 50% Life span in US | 0.51 | <0.001 | 0.44 | <0.001 |

| Foreign-born, 25–50% Life span in US | 0.47 | <0.001 | 0.50 | 0.004 |

| Foreign-born, < 25% Life span in US | 0.46 | 0.002 | 0.43 | <0.001 |

| English Proficiency | ||||

| Limited English Proficiency - reference | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Good English Proficiency | 1.00 | 0.98 | 1.09 | 0.61 |

| Sociodemographic Covariates | ||||

| Age | ||||

| 18–34 years – reference | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 35–49 years | 1.16 | 0.26 | 0.85 | 0.29 |

| 50–64 years | 1.38 | 0.09 | 0.86 | 0.47 |

| 65 years or more | 1.29 | 0.34 | 0.98 | 0.94 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male - reference | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Female | 1.91 | <0.001 | 1.83 | <0.001 |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Married/cohabitating – reference | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Divorced/separated/widowed | 1.08 | 0.75 | 1.56 | 0.04 |

| Never married | 1.27 | 0.18 | 0.90 | 0.56 |

| Education | ||||

| 11 years or less – reference | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 12 years | 1.51 | 0.01 | 0.67 | 0.13 |

| 13–15 years | 1.32 | 0.14 | 0.85 | 0.51 |

| 16 years or more | 2.14 | 0.001 | 1.19 | 0.51 |

| Household Income | ||||

| $0–$14,999 - reference | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| $15,000–$34,999 | 0.93 | 0.64 | 1.22 | 0.37 |

| $35,000–$74,999 | 1.23 | 0.25 | 0.93 | 0.76 |

| $75,000+ | 1.07 | 0.67 | 1.17 | 0.53 |

| Employment | ||||

| Employed – reference | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| Unemployment | 0.88 | 0.61 | 1.04 | 0.84 |

| Out of Labor Force | 1.42 | 0.02 | 0.70 | 0.04 |

| Clinical Covariates | ||||

| Chronic Medical Conditions | ||||

| 0 – reference | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||

| 1 | 3.12 | <0.001 | 1.78 | <0.001 |

| ≥ 2 | 4.49 | <0.001 | 3.65 | <0.001 |

| Psychological Distress (K10 score, range 0–50) | 1.06 | <0.001 | 1.11 | <0.001 |

| Days out of role because of mental health problems (Range 0–30 days) | 0.96 | 0.02 | 0.97 | 0.06 |

| Cognitive Functioning Score (Range 0–100) | 1.01 | 0.25 | 0.99 | 0.50 |

| Mobility Score (Range 0–100) | 1.01 | 0.04 | 1.01 | 0.03 |

| Self-care Score (Range 0–100) | 0.99 | 0.006 | 1.03 | 0.22 |

| Social Functioning Score (Range 0–100) | 1.00 | 0.59 | 1.00 | 0.70 |

| Role Functioning Score (Range 0–100) | 1.01 | 0.001 | 1.01 | <0.001 |

Discussion

The prevalence of physical symptoms in the United States is associated with race/ethnicity and acculturation. Overall, non-Latino whites and Latinos report a similar number of physical symptoms and the percentages experiencing any physical symptom or a high symptom burden are similar. Some prior research has found higher rates of physical symptoms among Latinos,[6, 8, 18] whereas our findings indicate that rates do not differ once the influence of other individual characteristics are taken into account. This suggests that prior elevated rates of physical symptoms may reflect the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics (particularly psychological distress and chronic conditions) that are more common among Latinos as opposed to ethnicity per se. In contrast, relative to non-Latino whites, Asian Americans are less likely to report any physical symptoms, less likely to report multiple symptoms, and report fewer physical symptoms on average. Among both Latino and Asian Americans, greater acculturation, as evidenced by a multidimensional proxy indicator including nativity, parental nativity, and lifespan in the United States, was associated with increased physical symptoms. These findings were robust and persisted after accounting for potential confounders including psychological distress, disability, medical comorbidity, and access to healthcare.

Our results are contrary to the notion that certain racial/ethnic minorities have more physical symptoms, yet they are consistent with prior research demonstrating low rates of physical symptoms and a positive association between acculturation and physical symptoms among Chinese and Filipino American adolescents. [12] In both Latino and Asian Americans, physical symptoms were associated with psychological distress, functional impairment, and chronic medical conditions, thereby extending the existing evidence documenting substantial overlap between psychological and physical symptoms to these groups. [5, 32] Our findings that Asian Americans reported fewer symptoms than whites and that less acculturated Latino and Asian Americans reported fewer symptoms than their more acculturated counterparts are in accord with a large body of literature documenting better mental health and lower rates of substance use disorders among some immigrant and racial/ethnic minority groups relative to non-Latino white Americans. [33–35] Similarly, our findings are consistent with prior studies demonstrating that certain chronic diseases, such as hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and diabetes are less common among less acculturated groups. [36–38] As such, these findings contribute further evidence supporting the ‘healthy immigrant’ effect whereby recently-arrived immigrants to the United States have better health status than their counterparts who have lived in the United States for longer periods of time. Although the mechanisms underlying these patterns are not well-understood, the present study suggests that the manifestations extend beyond substance use and emotional symptoms to include general physical symptoms.

These findings contrast with the conventional wisdom that racial/ethnic minorities, particularly those with low levels of acculturation, have the most physical symptoms. Symptom self-reports such as the one used in this study conflate the experience of the symptom with symptom reporting which is known to be socially patterned. In sensitivity analyses, we restricted the sample to participants who accessed health services, which reduces the possible impact of bias associated with lower healthcare service use among racial/ethnic minorities, particularly those with low acculturation. The data reported here suggest that the perception that physical symptoms are more common among racial/ethnic minorities, cannot be accounted for by a higher prevalence of symptoms among these groups. It is plausible that this perception results from other aspects of patient-physician interaction that were not measured as part of this epidemiological survey. Racial/ethnic groups may differ in the manner in which they discuss symptoms with providers, including the amount of time spent discussing a single symptom, the meaning or emphasis placed on a given symptom, the urgency with which symptoms are communicated, or the likelihood of offering symptoms that match the service setting. In one study of patient-provider communication in mental health settings, Latinos discussed physical symptoms less than whites did despite endorsing symptoms at similar rates. [39] Alternately, it is plausible that patterns may differ between community samples and clinical samples. For example, some evidence suggests that racial/ethnic minorities are more likely to delay seeking care thus, may present to healthcare providers only once symptoms are severely disabling. [40] Conversely, physicians may arrive at the encounter with biases toward the preferential discussion of biomedical rather than mental health topics [41] and patients may respond to the cues in physician behavior. Indeed, an international study demonstrated that physical symptoms were reported more by depressed patients who received their care in walk-in settings as opposed to settings where they had a personal physician. [3] A further possibility is that the perception of excess physical symptoms among racial/ethnic minorities reflects historical patterns of communication of symptoms and diagnosis that have changed over time. Such an evolution has occurred over the last thirty years for the symptoms and diagnosis of neurasthenia in China. [42]

Although it has been suggested that high burdens of physical symptoms among racial/ethnic minorities may contribute to under-detection of concurrent mental health problems, [3, 11] findings from the current research suggest that this explanation may be insufficient because physical symptoms were not more common among Latino and Asian Americans than whites. Similarly, some recent studies have found that physical symptoms are associated with increased, rather than decreased, perception of mental health problems. [43–45] Thus, the presence of concurrent physical symptoms is an unlikely explanation for the documented disparities in receipt of mental health care among racial/ethnic minorities.

Some limitations of the present study deserve notation. First, this community-based sample excluded individuals who were hospitalized, incarcerated, or otherwise institutionalized, which may exclude the most severely ill people. The reporting of physical symptoms may have been subject to recall bias and symptom reporting is inherently subjective and subject to limitations associated with self-reports. It is not possible to discern whether the observed differences across racial/ethnic groups reflect differences in the true prevalence of symptoms or differences in the threshold for reporting symptoms. The restriction to frequent or severe symptoms occurring within the last year and the inclusion of only symptoms discussed with a physician may have mitigated potential biases by restricting the analyses only to symptoms that were considered by participants to be serious. Discussion of a symptom may reflect help-seeking rather than severity. However, our analyses using lifetime symptoms without requiring discussion with a provider yielded the same results among Asians and similar results among Latinos, together suggesting that our findings are not explained by different help-seeking patterns across groups. Although a standardized measure of physical symptoms was not employed, twelve of the fourteen symptoms measured in this study are identical to symptoms of the PHQ-15. [46] Because past research indicates that these physical symptoms are associated with psychopathology and mental health service use regardless of whether symptoms are considered “explained” versus “unexplained”, we chose not to include this distinction in our report of symptom prevalence. The measurement of acculturation was based on proxy measures that have been used successfully in prior studies but do not capture many important aspects of the acculturative process such as social integration and change in social networks. Finally, a relatively small number of non-Latino whites participated, which may affect the reliability of the estimates for this group. However, analyses of acculturation were conducted separately among Asian and Latino groups and thus, would not have been affected by the relative small number of non-Latino white participants.

As the first nationally-representative study of physical symptoms among major racial/ethnic groups in the United States, the present study makes an important contribution to the literature in documenting the prevalence of symptoms and their associations with race/ethnicity and acculturation. Future research in clinical settings is warranted to further understand how patient-physician communication around physical symptoms may vary according to race/ethnicity, acculturation and patient-provider language concordance.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The NLAAS data used in this analysis were provided by the Center for Multicultural Mental Health Research at the Cambridge Health Alliance. The authors gratefully acknowledge financial support from the Dupont-Warren and Livingston Fellowships of the Department of Psychiatry at Harvard Medical School and training grant T32 MH20021 from the National Institute of Mental Health. NIH Research Grant # U01 MH62209 funded by the National Institute of Mental Health as well as the Substance Abuse & Mental Health Services Administration/Center for Mental Health Services and the Office of Behavioral and Social Science Research. This publication was also made possible by Grant # P60 MD002261-01 from the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NCMHD) and Grant #P50 MH073469-02 from the National Institute of Mental Health. A preliminary version of this report was presented at the annual meeting of the Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine in Phoenix AZ, November 2011.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Escobar JI, Golding JM, Hough RL, et al. Somatization in the community: relationship to disability and use of services. Am J Public Health. 1987;77:837–840. doi: 10.2105/ajph.77.7.837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kroenke K, Price RK. Symptoms in the community. Prevalence, classification, and psychiatric comorbidity. Arch Intern Med. 1993;153:2474–2480. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simon GE, VonKorff M, Piccinelli M, Fullerton C, Ormel J. An international study of the relation between somatic symptoms and depression. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1329–1335. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910283411801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kisely S, Simon G. An international study comparing the effect of medically explained and unexplained somatic symptoms on psychosocial outcome. J Psychosom Res. 2006;60:125–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.06.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Escobar JI, Cook B, Chen CN, et al. Whether medically unexplained or not, three or more concurrent somatic symptoms predict psychopathology and service use in community populations. J Psychosom Res. 2010;69:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Escobar JI, Burnam MA, Karno M, Forsythe A, Golding JM. Somatization in the community. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1987;44:713–718. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800200039006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bhatt A, Tomenson B, Benjamin S. Transcultural patterns of somatization in primary care: a preliminary report. J Psychosom Res. 1989;33:671–680. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(89)90082-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Escobar JI, Rubio-Stipec M, Canino G, Karno M. Somatic symptom index (SSI): a new and abridged somatization construct. Prevalence and epidemiological correlates in two large community samples. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1989;177:140–146. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198903000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Canino IA, Rubio-Stipec M, Canino G, Escobar JI. Functional somatic symptoms: a cross-ethnic comparison. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 1992;62:605–612. doi: 10.1037/h0079376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Parker G, Gladstone G, Chee KT. Depression in the planet's largest ethnic group: the Chinese. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:857–864. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.6.857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lewis-Fernández R, Das AK, Alfonso C, Weissman MM, Olfson M. Depression in US Hispanics: diagnostic and management considerations in family practice. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2005;18:282–296. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.18.4.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Willgerodt MA, Thompson EA. Ethnic and generational influences on emotional distress and risk behaviors among Chinese and Filipino American adolescents. Res Nurs Health. 2006;29:311–324. doi: 10.1002/nur.20146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kirmayer L, Sartorius N. Cultural Models and Somatic Syndromes. Psychosom Med. 2007;69:832–840. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31815b002c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirmayer LJ, Young A. Culture and somatization: clinical, epidemiological, and ethnographic perspectives. Psychosom Med. 1998;60:420–430. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199807000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Escobar J, Gureje O. Influence of Cultural and Social Factors on the Epidemiology of Idiopathic Somatic Complaints and Syndromes. Psychosom Med. 2007;69:841–845. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31815b007e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kroenke K. Patients presenting with somatic complaints: epidemiology, psychiatric comorbidity and management. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2003;12:34–43. doi: 10.1002/mpr.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Regier DA, Myers JK, Kramer M, et al. The NIMH Epidemiologic Catchment Area program. Historical context, major objectives, and study population characteristics. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1984;41:934–941. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1984.01790210016003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang AY, Snowden LR. Ethnic characteristics of mental disorders in five U.S. communities. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 1999;5:134–146. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.5.2.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health; 1999. Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. [Google Scholar]

- 20.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Rockville, MD: Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services; 2001. Mental Health: Culture, Race, and Ethnicity: A Supplement to Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heeringa SG, Wagner J, Torres M, et al. Sample designs and sampling methods for the Collaborative Psychiatric Epidemiology Studies (CPES) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:221–240. doi: 10.1002/mpr.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alegria M, Takeuchi D, Canino G, et al. Considering context, place and culture: the National Latino and Asian American Study. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:208–220. doi: 10.1002/mpr.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alegria M. The challenge of acculturation measures: what are we missing? A commentary on Thomson &Hoffman-Goetz. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69:996–998. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thomson MD, Hoffman-Goetz L. Defining and measuring acculturation: a systematic review of public health studies with Hispanic populations in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69:983–991. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abe-Kim J, Takeuchi D, Hong S, et al. Use of mental health-related services among immigrant and US-born Asian Americans: Results from the National Latino and Asian American Study. Am J Public Health. 2006;97:91–98. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.098541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pippins JR, Alegria M, Haas JS. Association between language proficiency and the quality of primary care among a national sample of insured Latinos. Med Care. 2007;45:1020–1025. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31814847be. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bauer AM, Chen CN, Alegria M. English language proficiency and mental health service use among Latino and Asian Americans with mental disorders. Med Care. 2010;48:1097–1104. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181f80749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andrews G, Slade T. Interpreting scores on the Kessler Psychological Distress Scale (K10) Aust N Z J Public Health. 2001;25:494–497. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2001.tb00310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, et al. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med. 2002;32:959–976. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rehm J, Üstün TB, Saxena S, et al. On the development and psychometric testing of the WHO screening instrument to assess disablement in the general population. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 1999;8:110–122. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rao JNK, Scott AJ. On chi-squared tests for multi-way tables with cell proportions estimated from survey data. Annals of Statistics. 1984;12:46–60. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, et al. Physical symptoms in primary care. Predictors of psychiatric disorders and functional impairment. Arch Fam Med. 1994;3:774–779. doi: 10.1001/archfami.3.9.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alegria M, Canino G, Shrout PE, et al. Prevalence of mental illness in immigrant and non-immigrant U.S. Latino groups. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:359–369. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07040704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vega WA, Canino G, Cao Z, Alegria M. Prevalence and correlates of dual diagnoses in U.S. Latinos. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;100:32–38. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gonzalez HM, Tarraf W, Whitfield KE, Vega WA. The epidemiology of major depression and ethnicity in the United States. J Psychiatr Res. 2010;44:1043–1051. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Steffen PR, Smith TB, Larson M, Butler L. Acculturation to Western society as a risk factor for high blood pressure: a meta-analytic review. Psychosom Med. 2006;68:386–397. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000221255.48190.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mojtabai R. Social comparison of distress and mental health help-seeking in the US general population. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67:1944–1950. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Teppala S, Shankar A, Ducatman A. The association between acculturation and hypertension in a multiethnic sample of US adults. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2010;4:236–243. doi: 10.1016/j.jash.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carson N, Katz AM, Gao S, Alegría M. Assessment of physical illness by mental health clinicians during intake visits. Psychiatr Serv. 2010;61:32–37. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.61.1.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang PS, Berglund P, Olfson M, et al. Failure and delay in initial treatment contact after first onset of mental disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:603–613. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tai-Seale M, McGuire T, Colenda C, Rosen D, Cook MA. Two-minute mental health care for elderly patients: inside primary care visits. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:1903–1911. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee S, Kleinman A. Are Somatoform Disorders Changing With Time? The Case of Neurasthenia in China. Psychosom Med. 2007;69:846–849. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31815b0092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Vera M, Alegría M, Freeman DH, Jr, et al. Help seeking for mental health care among poor Puerto Ricans: problem recognition, service use, type of provider. Med Care. 1998;36:1047–1056. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199807000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mojtabai R, Olfson M, Mechanic D. Perceived need and help-seeking in adults with mood, anxiety, or substance use disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:77–84. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nadeem E, Lange JM, Miranda J. Perceived need for care among low-income immigrant and U.S.-born black and Latina women with depression. J Womens Health. 2009;18:369–375. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2008.0898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-15: validity of a new measure for evaluating the severity of somatic symptoms. Psychosom Med. 2002;64:258–266. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200203000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.