Abstract

Objective

The present study examined (a) the interactions between early behavior, early parenting, and early family adversity in predicting later ODD symptoms, and (b) the reciprocal relations between parent functioning and ODD symptoms across the preschool years.

Method

Participants were 258 3-year-old children (138 boys and 120 girls) and their parents from diverse backgrounds who participated in a 4-year longitudinal study.

Results

Early child behavior, parenting, and family adversity did not significantly interact in the predicted direction. Reciprocal relations between ODD symptoms and parent functioning were observed for maternal and paternal depression, and maternal warmth. Paternal laxness at age 4 predicted ODD symptoms at age 5 and paternal laxness at age 5 predicted ODD symptoms at age 6, but child ODD did not significantly predict paternal laxness.

Conclusion

Results suggest that ODD symptoms may develop through a transactional process between parent and child functioning across the preschool years.

Keywords: oppositional defiant disorder, parenting, longitudinal, preschool aged children

Oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) is one of the most common childhood disorders, affecting approximately 2–16% of children (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). It is characterized by a recurring pattern of negative, hostile, disobedient, and defiant behavior. ODD symptoms often cause disruption in a number of domains, including social (Frankel & Feinberg, 2002), family (Loeber, Lahey, & Thomas, 1991), and academic functioning (Gadow & Nolan, 2002). The nature and etiology of ODD has been widely studied, although much of the literature has not historically used the DSM criteria for ODD, but rather has focused on antisocial behavior, aggression, conduct problems, and externalizing behavior, which are highly related to if not synonymous with ODD symptoms.

Etiological models suggest that interactions between early child characteristics, family adversity, and parenting lead to the development of ODD (Barkley, DuPaul, & McMurray, 1990; Lahey & Waldman, 2003; Moffitt, 1993). Moreover, reciprocal relations between child behavior and family experiences may contribute to the maintenance of behaviors associated with ODD (Patterson, 1982). The preschool years are likely a critical period during which these processes unfold. Prospectively examining the interplay between family factors and ODD symptoms across the preschool years is key to further understanding the early development of ODD.

Etiological Models of ODD

Research suggests that environments (Burt, Krueger, McGue, & Iocono, 2001) and biological factors, including genetics and prenatal and perinatal complications (Brennan, Grekin, & Mednick, 2003), play a role in the development of ODD. In particular, largely heritable characteristics, including negative emotionality and hyperactivity/impulsivity are thought to increase children’s propensity to exhibit behavior problems by contributing to and interacting with family adversity and parenting behaviors (Barkley, 1990; Lahey & Waldman, 2003; Moffitt, 1990). Implicit in these models are reciprocal effects of parents and children on one another. Such effects have been emphasized in a number of theoretical models of the development of child behavior problems (Shaw & Bell, 1993), including Bell’s (1977) control systems theory and Patterson’s (1982) coercive cycle, which posits that children’s antisocial behavior elicits aversive reactions from parents, which, in turn, exacerbate children’s antisocial behavior.

Empirical Literature on Key Etiological Factors

Considerable research points to the importance of early behavior, family adversity, and parenting in the development of ODD. First, research indicates that early child characteristics put children at risk for later behavior problems. For example, over half of preschool-aged children with ODD continue to meet criteria for ODD when they reach school-age (Speltz, McClellan, DeKlyen, & Jones, 1999). Second, parenting practices have been consistently linked to children’s oppositional-defiant and conduct problems. More specifically, dysfunctional parenting practices, including negativity and lack of warmth (Barkley, Fischer, Edelbrock, & Smallish, 1991; Kashdan et al., 2004; Pfiffner, McBurnett, & Rathouz, 2005), permissiveness/inconsistency (Taylor, Schachar, Thorley, & Wieselberg, 1986), and lack of responsiveness (Johnston, Murray, & Hinshaw, 2002; Seipp & Johnston, 2005) have been linked to ODD symptoms or related conduct problems. Research that has focused on preschool-aged children has also found that negative parent-child interactions are associated with children’s current (Calkins, Smith, Gill, & Johnson, 1998; Cunningham & Boyle, 2002; Eiden, Edwards, & Leonard, 2007; Keown & Woodward, 2002; Shaw, Keenan, & Vondra, 1994) and future (Campbell & Ewing, 1990; Campbell, March, Pierce, Ewing, & Szumowski, 1991; DeKlyen, Speltz, & Greenberg, 1998; Heller, Baker, Henker, & Hinshaw, 1996) conduct problems. Third, family adversity, including low socioeconomic status (SES) and parental depression, have been well-established correlates of conduct problems in children. Preschool children who live in poverty are at greater risk for the development of conduct problems than are children from higher SES backgrounds (Qi & Kaiser, 2003). Both maternal depression (Elgar, McGrath, Waschbusch, Stewart, & Curtis, 2004) and paternal depression (Spector, 2006) have been linked with conduct problems in children. A handful of longitudinal studies have also documented a link between maternal depression when children are very young and later externalizing problems (e.g., Cummings & Davies, 1994; Downey & Coyne, 1990; Goodman & Gotlib, 1999; Lovejoy, Graczyk, O’Hare, & Neuman, 2000).

Interactions Between Early Child Characteristics, Parenting, and Family Adversity

Although early child characteristics, parenting, and family adversity have all been linked with ODD/conduct problems, only a handful of studies have directly examined interactions among these variables, which lie at the heart of many models of ODD. Shaw, Winslow, Owens, Vondra, Cohn, and Bell (1998) found that high maternal rejection and high child noncompliance at age 1 interacted in predicting higher externalizing behavior scores at age 3 1/2. Similarly, Brennan et al. (2003) found stronger relations between biological influences (i.e., perinatal risk factors) and aggression when coupled with low SES and poor family functioning. Finally, Moffitt (1990) reported a stronger relation between early and later behavior problems in the presence of higher levels of family adversity. Thus, the few studies that have examined interactions between early risk factors for later conduct problems suggest that this area warrants further study.

Reciprocal Relations Between Early Family Experiences and Behavior Problems

There is substantial empirical evidence of a reciprocal relation between family experiences and conduct problems. More specifically, there is evidence that supports both child effects and parent effects models. Experimental research suggests that mothers use more restrictive parenting when interacting with children exhibiting conduct problems (Brunk & Henggler, 1984), and parent training studies have consistently demonstrated that when parents learn new ways of interacting with their children, conduct problems also improve (Webster-Stratton & Taylor, 2001). Child effects of conduct problems have also been demonstrated on parent distress and alcohol consumption (Pelham et al., 1997), and parent effects of maternal depression on child externalizing problems have been demonstrated experimentally (Pilowsky et al., 2008). Longitudinal studies have also supported reciprocal relations between externalizing problems and both parenting (e.g., Lansford et al., 2011; Sheehan & Watson, 2008; Vuchinich, Bank, & Patterson, 1992) and parental depression (Gross, Shaw, Moilanen, Dishion, & Wilson, 2008), with some evidence that effects vary as a function of child age (Pardini, Fite, & Burke, 2008). However, research has focused largely on middle to late childhood and adolescence; more research is needed to understand parent and child influences early in development when conduct problems are often first emerging. More research is also needed to better understand the reciprocal relation between fathers’ functioning and children’s conduct problems. Finally, although researchers have examined reciprocal relations between family functioning and externalizing problems, examination of ODD symptoms specifically is important for developing and testing etiological models of this disorder.

The Present Study

Although research suggests that there are links between early child characteristics, parenting, family adversity, and ODD symptoms, there is a gap in the literature regarding the interplay among these variables across the preschool years when ODD symptoms may be first developing. We have found that these factors at age 3 predict ODD symptoms at age 6 in our longitudinal study of the early development of ADHD and ODD (Authors, 2011). The proposed study seeks to extend these findings by (a) examining the interaction between early externalizing problems, early parenting practices, and early family adversity in predicting later ODD symptoms, and (b) examining the reciprocal relations between parent functioning and ODD symptoms across the preschool years. The study will test three predictions:

The relation between early externalizing problems and later ODD symptoms will be moderated by early parenting (warmth, overreactivity/negative affect, and laxness) and early family adversity (parent depression and parent education), such that there is a stronger relation between early externalizing problems and later ODD in the presence of less warmth, more overreactivity/negative affect, more laxness, and greater family adversity.

The relation between early family adversity and later ODD symptoms will be moderated by early parenting, such that there is a stronger relation between early family adversity and later ODD in the presence of less warmth, more overreactivity/negative affect, and more laxness.

There will be evidence for reciprocal relations between symptoms of ODD and parent functioning. In particular, it was hypothesized that lower parental warmth and greater overreactivity, laxness, and depression at ages 3, 4, and 5 would predict more ODD symptoms one year later, and more ODD symptoms at ages 3, 4, and 5 would predict lower parental warmth and greater overreactivity, laxness, and depression one year later.

Method

Participants

Participants were 258 children (138 boys and 120 girls) and their 258 mothers and 207 fathers who participated in a longitudinal study from age 3 to 6. The children were all 3 years old at the time of initial screening and were 36 to 50 months (M = 44.15 months, SD = 3.37) at the time of the first home visit. The sample consisted of 55% European American children, 18% Latino children (predominantly Puerto Rican), 12% African-American children, and 15% multiethnic children. One hundred ninety-nine of these children had significant externalizing problems (hyperactivity and/or aggression) at the time of screening and 59 children did not have behavioral problems. The median combined family income at Time 1 was $48,000. Most mothers (87.5%) and fathers (91.5%) had a high school diploma and 33.3% of mothers and 30% of fathers had bachelor’s degrees. Of the 258 mothers, 258 completed at least one measure at Time 1, 243 at Time 2, 215 at Time 3, and 220 at Time 4. Of the 207 fathers, 180 completed at least one measure at Time 1, 172 at Time 2, 145 at Time 3, and 146 at Time 4.

Procedure

Participants were recruited by distributing questionnaire packets through birth records, pediatrician offices, childcare centers, and community centers throughout Western Massachusetts. The questionnaire packet contained an informed consent form, a Behavior Assessment System for Children-Parent Report Scale (BASC-PRS, described in more detail below), and a questionnaire assessing for exclusion criteria, parental concern about externalizing symptoms, and demographic information. Criteria for all participants included no evidence of mental retardation, deafness, blindness, language delay, cerebral palsy, epilepsy, autism, or psychosis. Criteria for the externalizing group were: (a) parent responded “yes” or “possibly” to the question, “Are you concerned about your child’s activity level, defiance, aggression, or impulse control?” and (b) BASC-PRS hyperactivity and/or aggression subscale T scores fell at or above 65 (approximately 92nd percentile). Criteria for the non-problem comparison children were: (a) parent responded “no” to the question, “Are you concerned about your child’s activity level, defiance, aggression, or impulse control?” and (b) T scores on the BASC-PRS hyperactivity, aggression, attention problems, anxiety, and depression subscales fell at or below a T score of 60. Parents whose children met criteria listed above for either the externalizing group or nonproblem group (who were matched to 59 randomly selected children in the externalizing group on age, gender, maternal education, and ethnicity) were invited to participate in yearly home visit assessments from age 3 to age 6. Families were paid for their participation. Written informed consent was obtained from all parents who participated and verbal assent was obtained from children. The study was conducted in compliance with the authors’ Internal Review Board.

Measures

Family adversity

Socioeconomic Status

A measure of parents’ education level was used as a proxy for SES. Mothers’ and fathers’ education were significantly correlated, r (205) = .68, p < .001.

Parent depression

The Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory-III (MCMI-III; Millon, Davis, & Millon, 1997), which is a widely-used self-report questionnaire that measures adult psychopathology, was used to assess parent depressive symptomatology. The internal consistency for the MCMI-III scales in a clinical population ranged from .66 to .90; test-retest reliabilities ranged from .84 to .96 (Millon et al., 1997). In the present study, the MCMI-III subscales that assess Major Depression, Dysthymia, and Depressive personality were administered at Times 1, 2, 3 and 4. Since we were interested in assessing current depression, 8 of the 33 items were omitted from analyses because they assess symptoms over a long time-frame. Following instructions from MCMI-III manual (Millon et al., 1997), items considered prototypical for the Major Depression scale were double-weighted. Prototypical items from the Dysthymia and Depressive personality scales were not double-weighted since they represent less severe symptoms. Responses to the 25 items were summed to create a raw score, with higher scores indicating greater levels of depressive symptomatology. These 25 items demonstrated good internal consistency in the present sample (Cronbach’s alpha was .92 for mothers and .93 for fathers at Time 1). Mothers’ and fathers’ depression scores were significantly correlated at each time point, and ranged from r (205) = .39, p < .001, at Time 4 to r (205) = .55, p < .001, at Time 2.

Child behavior

Early externalizing behavior

The BASC-PRS is a 131-item comprehensive rating scale that assesses a broad range of psychopathology in children ages 2 years 6 months and older (Reynolds & Kamphaus, 1992). Parents are asked to rate on a four point scale (Never, Sometimes, Often, Almost Always) the degree to which each item describes their children. The BASC-PRS demonstrates good reliability and validity with preschool age children (Reynolds & Kamphaus, 1992). Mothers and fathers independently completed the BASC-PRS Preschool Version at Time 1. The 26-item Externalizing scale was used in the present study and raw scores were converted to T-score using General Norms. Cronbach’s alpha for the Externalizing scale was .93 for both mothers and fathers. Mothers’ and fathers’ externalizing scores were significantly correlated, r (205) = .57, p < .001.

ODD symptoms

Mothers and fathers independently completed the Disruptive Behavior Rating Scale-Parent Version (DBRS-PV; Barkley & Murphy, 1998) at each time point. This scale includes items related to the 18 DSM-IV symptoms for ADHD and 8 DSM-IV symptoms for ODD, and parents rate how often these symptoms occurred in the past 6 months from 0 (not at all) to 3 (very often). Ratings for the 8 ODD items were averaged separately for mothers and fathers at each time point. This scale has demonstrated good reliability and validity (Authors, 2009). Cronbach’s alpha ranged from .89 to .91 for mothers and from .88 to .90 for fathers across the four time points. Mothers’ and fathers’ ODD scores were significantly correlated at each time point, and ranged from r (205) = .56, p < .001, at Time 3 to r (205) = .59, p < .001, at Time 4.

Parenting

Videotaped assessment of parenting

At each time point, children were videotaped interacting with their mothers during a 5-min play task and a clean-up task. At Time 1, mothers and children were also videotaped during a 10-min forbidden object task. Fathers did not take part in videotaped observations because of time limitations during the home visits. Each tape was coded by two independent raters (whose ratings were averaged) using a coding system developed for this study, which was adapted from Arnold, O’Leary, Wolff, & Acker (1993) who used a similar method of assessing parenting. Raters were undergraduate research assistants who were unaware of the children’s behavior status. Raters received extensive training, including reviewing their practice coding during weekly meetings for approximately 7 weeks. Global warmth ratings were used in the present study. Warmth referred to the extent to which the parent was positively attentive to the child; used praise, encouragement, and terms of endearment; conveyed affection; was supportive and available; was cheerful in mood and tone of voice; and/or conveyed interest, joy, enthusiasm, and warmth in interactions with the child. Warmth was rated on a scale from 1 (no warmth) to 7 (high level of warmth). For analyses involving only Time 1 warmth, ratings across all three tasks were averaged. For analyses involving warmth across all four time points, ratings across the two tasks that were repeated at each time point (play and clean up) were used. Intraclass correlations were .81 for warmth across the three tasks at Time 1 and averaged .70 across the four time points.

Audiotaped assessment of parenting

In order to obtain a more naturalistic, less reactive measure of parenting, mothers and fathers were each asked to use a micro-cassette player to record 2 hours of interaction with their children at Time 1, selecting times of day that tended to be challenging for them as parents. A preliminary review of the tapes suggested that 30 min of tape was sufficient for capturing a wide variety of behavior that was representative of the entire 2 hrs, and all parents who took part in this assessment completed at least 30 min. Graduate students who were unaware of the children’s behavior status rated the first 15 min of each side of one tape. Training involved approximately 40 hrs of practice coding which was reviewed during weekly meetings. Two raters overlapped for 88 participants and intraclass correlations (ICCs) were calculated to determine reliability for each code. The coding system was adapted from a system developed by the authors in a previous study (Authors, 2006) and included both event-based and global coding. This method of recording and coding parenting has been shown to be sensitive to detecting changes in parent-child interactions following parent training (Authors, 2006). In this study, the codes for parent warmth and parent negative affect were used. Global ratings of parent warmth (ICC = .53) were made every 5 minutes and ranged from 1 (not warm) to 7 (extremely warm). Each instance of parent negative affect was rated on a scale from 1 (slight) to 6 (strong), and these ratings were summed across the 30 min of interaction to create a parent negative affect score (ICC = .60). Both maternal and paternal warmth and negative affect ratings at Time 1 were found to distinguish children who entered this study with behavior problems from children without behavior problems, all ps < .05, providing support for the validity of this measure. Mothers and fathers ratings were significantly correlated with each other for warmth, r (205) = .22, p = .001, and negative affect, r (205) = .28, p < .001.

Self-report of parenting

Mothers and fathers completed the Parenting Scale at Time 1 (Arnold et al., 1993), which is a 30-item self-report scale. Ratings are made using a 7-point Likert scale, with anchors that vary across items. This scale yields scores for laxness (e.g., “When I say my child can’t do something…I let my child do it anyway [7] vs. I stick to what I said [1]”) and overreactivity (e.g., “When my child misbehaves…I get so frustrated or angry that my child can see I’m upset [7] vs. I handle it without getting upset [1]”), which are two types of parenting practices that have been hypothesized to play a key role in coercive interactions (Patterson, 1982). Scores were calculated by averaging across items that loaded on each factor according to the Arnold et al. (1993) factor structure, where high scores indicate dysfunctional parenting. This scale has demonstrated good reliability and validity among preschoolers (Arnold et al., 1993). Moreover, the overreactivity factor has been found to predict later child behavior problems among young preschool children (O’Leary, Smith Slep, & Reid, 1999). This scale demonstrated adequate reliability in the present sample (Cronbach’s alphas at Time 1 were .71 and .76 for overreactivity and .83 and .75 for laxness for mothers and fathers, respectively). Mothers’ and fathers’ reports of overreactivity were not significantly correlated with each other except for a modest correlation at Time 2, r (205) = .16, p = .02. Mothers’ and fathers’ reports of laxness were significantly correlated with each other only at Time 2, r (205) = .22, p = .001, and Time 3, r (205) = .20, p = .004, and these correlations were modest in size.

Results

Analytic Plan

Missing data were imputed using SPSS to create five imputed datasets. The imputation option was used in MPLUS 6 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2010), which provides estimates that are aggregated across the five datasets. To test interactions among child and family variables in predicting ODD outcome, latent growth curve modeling was conducted using MPLUS 6. Two components of ODD outcome were of interest: (a) rate of change in ODD symptoms, and (b) level of ODD symptoms at Time 4. Unconditional growth models were used to estimate ODD trajectories and consisted of two latent growth factors (intercept and slope). A quadratic term was also specified, but it was not significant so it was not included in the models. These latent growth factors were then used as outcome variables, with Time centered at Time 4 (Time was coded -3, -2, -1, and 0) so that the intercept would indicate Time 4 ODD symptom levels. Models were estimated separately for mothers and fathers.

To test the interaction of each pair of child and family variables (child externalizing symptoms, parenting practices, and family adversity [SES and parent depression]), each latent growth factor (intercept and slope) was regressed on the two child/family variables and a product term created by multiplying the two child/family variables. For interactions between parenting practices and family adversity variables, child externalizing symptoms was also added as a predictor of the intercept and slope in order to control for early child behavior. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to determine whether parenting variables assessing the same or similar constructs could be combined to form latent variables.

To examine the reciprocal relations between ODD symptoms and family variables, a series of cross-lagged panels were estimated using MPLUS 6 for family variables that were repeated at each time point (parent overreactivity and laxness, videotaped maternal warmth, and parent depression). For each model, ODD symptoms and the family variable were examined across the 4 time points, and each variable was regressed on the two variables from the preceding time point. Fathers’ reports of ODD symptoms were used for father models and mothers’ reports of ODD symptoms were used for mothers’ models. Residuals were allowed to correlate within measure across time point and across measures within time points when suggested by modification indices. Models were each tested allowing cross-lagged associations to vary across time, and then were estimated first holding paths from parent variables to child ODD constant across time and then holding paths from child ODD to the parent variable constant. If fixing paths across time did not result in a significantly worse model fit, based on the Chi-square fit index, those paths were set to be fixed across time.

Preliminary Analyses

Table 1 presents means and standard deviations for variables at each time point (based on imputed data). Intercorrelations among measures (Table 2) indicated that child and parent functioning were generally correlated in the expected direction.

Table 1.

Means and Standard Deviations of Child and Family Variable Across Time

| Time 1 | Time 2 | Time 3 | Time 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |

| Mothers (N = 258) | ||||||||

| Maternal years of education | 13.46 | 2.75 | ||||||

| Child BASC externalizing | 58.79 | 13.94 | ||||||

| Child DBRS ODD | 1.07 | 0.70 | 1.12 | 0.70 | 1.07 | 0.72 | 1.09 | 0.75 |

| Maternal depression | 5.48 | 6.19 | 5.60 | 7.03 | 5.17 | 6.73 | 5.02 | 6.10 |

| Maternal overreactivity | 2.70 | 0.75 | 2.71 | 0.76 | 2.64 | 0.75 | 2.71 | 0.79 |

| Maternal laxness | 2.96 | 1.03 | 2.76 | 0.96 | 2.69 | 0.99 | 2.72 | 0.96 |

| Maternal videotaped warmth | 4.38 | 1.11 | 4.28 | 0.98 | 4.41 | 0.61 | 4.23 | 0.55 |

| Maternal audiotaped warmth | 4.47 | 1.05 | ||||||

| Maternal audiotaped negative affect | 2.80 | 2.46 | ||||||

| Fathers (N = 207) | ||||||||

| Paternal years of education | 13.49 | 2.67 | ||||||

| Child BASC externalizing | 54.58 | 13.85 | ||||||

| Child DBRS ODD | 0.91 | 0.63 | 0.93 | 0.62 | 0.88 | 0.66 | 0.92 | 0.62 |

| Paternal depression | 3.70 | 4.87 | 3.21 | 4.19 | 3.94 | 5.58 | 3.35 | 4.52 |

| Paternal overreactivity | 2.51 | 0.80 | 2.72 | 0.77 | 2.66 | 0.85 | 2.67 | 0.88 |

| Paternal laxness | 2.75 | 0.86 | 2.83 | 0.88 | 2.78 | 0.87 | 2.87 | 0.88 |

| Paternal audiotaped warmth | 4.69 | 0.91 | ||||||

| Paternal audiotaped negative affect | 1.88 | 1.57 | ||||||

Note. BASC = Behavior Assessment System for Children. DBRS ODD = Disruptive Behavior Rating Scale-Parent Version Oppositional Defiant Disorder subscale.

Table 2.

Intercorrelations Among Child and Family Variables Across Time

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Years of education | -- | −.08 | −.11 | −.19** | .10 | −.13† | -- | .13† | −.08 | −.05 |

| 2. BASC Externalizing | −.21*** | -- | .74*** | .37*** | .18** | .22** | -- | −.14* | .15* | .37*** |

| 3. DBRS ODD | ||||||||||

| Time 1 | −.18*** | .75*** | -- | .35*** | .28*** | .32*** | -- | −.19** | .18** | .38*** |

| Time 2 | -- | .51*** | .30*** | .19** | -- | |||||

| Time 3 | -- | .42*** | .38*** | .27*** | -- | |||||

| Time 4 | -- | .44*** | .24*** | .27*** | -- | |||||

| 4. Depression | ||||||||||

| Time 1 | −.31*** | .29*** | .28*** | -- | .07 | .22** | -- | −.06 | .13† | .15* |

| Time 2 | .34*** | -- | .14* | .26*** | -- | |||||

| Time 3 | .36*** | -- | .22** | .13 | -- | |||||

| Time 4 | .44*** | -- | .26*** | .24*** | -- | |||||

| 5. Overreactivity | ||||||||||

| Time 1 | .00 | .29*** | .30*** | .29*** | -- | .13† | -- | −.12† | .19** | .21*** |

| Time 2 | .25*** | .27*** | -- | .10 | -- | |||||

| Time 3 | .37*** | .37*** | -- | .13† | -- | |||||

| Time 4 | .30*** | .22*** | -- | .12† | -- | |||||

| 6. Laxness | ||||||||||

| Time 1 | −.27*** | .29*** | .23*** | .34*** | .21*** | -- | -- | −.10 | .05 | .17* |

| Time 2 | .26*** | .35*** | .24*** | -- | -- | |||||

| Time 3 | .24*** | .34*** | .34*** | -- | -- | |||||

| Time 4 | .18** | .25*** | .36*** | -- | -- | |||||

| 7. Videotaped warmth | ||||||||||

| Time 1 | .30*** | −.13* | −.16* | −.24*** | .02 | −.28*** | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Time 2 | −.21*** | −.27*** | −.11 | −.20*** | -- | -- | -- | -- | ||

| Time 3 | −.11† | −.22*** | .02 | −.10 | -- | -- | -- | -- | ||

| Time 4 | −.14* | −.25*** | −.09 | −.28*** | -- | -- | -- | -- | ||

| 8. Audiotaped warmth | .42*** | −.35*** | −.31*** | −.27*** | −.13* | −.33*** | .32*** | -- | −.50*** | −.18** |

| 9. Audiotaped negative affect | .20*** | .27*** | .25*** | .25*** | .22*** | .29*** | −.15* | −.52*** | -- | .16* |

| 10.Behavior group (1) vs. nonproblem group (0) at Time 1 | −.10† | .53*** | .46*** | .24*** | .26*** | .12† | −.12† | −.17** | .17** | -- |

Note. BASC = Behavior Assessment System for Children. DBRS ODD = Disruptive Behavior Rating Scale-Parent Version Oppositional Defiant Disorder subscale. Fathers’ correlations (N = 207) are above the diagonal and mothers’ correlations (N = 258) are below the diagonal.

p < .10,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

CFA was conducted in order to determine whether parenting variables measuring similar constructs could be combined into latent variables. For mothers, CFA was conducted with maternal self-reported overreactivity and negative affect loading on one latent variable (Over/Neg) and maternal audio warmth and video warmth loading on a second latent variable (Warm). Model fit indices for this model were good, χ2(3) = 1.91, p = .59, RMSEA = .01, SRMR = .02, CFI = 1.00, and all factor loadings were significant (ps < .01). Maternal self-reported laxness was kept separate because it was a theoretically distinct construct, and because loading laxness on either the Warm or Over/Neg latent variables resulted in poor to mediocre model fit (for Warm, χ2(6) = 25.17, p = .02; RMSEA = .11, SRMR = .07, CFI = .89; for Over/Neg, χ2(6) = 33.02, p < .001, RMSEA = .13, SRMR = .09, CFI = .84.)

For fathers, CFA supported a single latent variable (Over/Neg vs. Warm) with significant standardized loadings for paternal self-reported overreactivity (.27, p = .004), audiotaped negative affect (.57, p = .001), and audiotaped warmth (−.62, p =.001). However, in order to facilitate comparisons between mothers and fathers and for theoretical reasons, audiotaped warmth was analyzed separately from overreactivity and negative affect. Paternal self-reported laxness was also kept separate because it was a theoretically distinct construct and because laxness did not load significantly on the Over/Neg vs. Warm factor (−.28, p = .12).

Although the focus of the present study was on the interactions between parenting and other measures of family functioning, some previous research has found interactions among parenting variables as well. Therefore, before testing the hypotheses of the present study, we first explored whether parenting variables interacted with one another in predicting ODD outcome, and they did not (all ps > .15). We therefore proceeded with treating each parenting dimensions separately.

Do Parenting and Family Adversity Moderate the Relation Between Early Externalizing Problems and ODD Symptoms?

Contrary to prediction, there were no significant interactions between early child behavior and maternal or paternal parenting or family adversity in predicting ODD change or Time 4 outcome (see Table 3 for interaction coefficients). Examination of boys and girls separately using multigroup analyses also yielded no significant interactions.

Table 3.

Interaction Coefficients Predicting Time 4 DBRS ODD Symptoms and Linear Rate of Change in DBRS ODD Symptoms

| Predictor | Predicting Time 4 ODD Symptoms (Intercept Growth Factor) | Predicting Linear Rate of Change in ODD Symptoms (Linear Growth Factor) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| γ (SE) | p | γ (SE) | p | |

| Mothers | ||||

| Laxness × BASC externalizing | −0.002 (0.001)† | .070 | −0.002 (0.001)† | .075 |

| Over/neg × BASC externalizing | −0.018 (0.016) | .250 | −0.008 (0.008) | .270 |

| Warm × BASC externalizing | 0.010 (0.010) | .276 | 0.001 (0.004) | .744 |

| Depression × BASC externalizing | 0.000 (0.000) | .617 | 0.000 (0.000) | .440 |

| Depression × laxnessa | −0.013 (0.006) | .042* | −0.003 (0.002) | .180 |

| Depression × over/nega | −0.014 (0.019) | .481 | −0.010 (0.007) | .120 |

| Depression × warma | 0.015 (0.017) | .366 | 0.008 (0.005) | .100 |

| Education × BASC externalizing | 0.000 (0.001) | .782 | 0.000 (0.000) | .570 |

| Education × laxnessa | −0.003 (0.013) | .792 | 0.008 (0.004) | .049* |

| Education × over/nega | −0.002 (0.037) | .962 | 0.017 (0.015) | .269 |

| Education × warma | 0.034 (0.027) | .200 | −0.005 (0.009) | .600 |

| Fathers | ||||

| Laxness × BASC externalizing | 0.002 (0.004) | .568 | 0.001 (0.002) | .649 |

| Over/neg × BASC externalizing | 0.014 (0.016) | .380 | −0.008 (0.006) | .222 |

| Warm × BASC externalizing | 0.003 (0.003) | .350 | 0.001 (0.001) | .328 |

| Depression × BASC externalizing | −0.001 (0.001) | .429 | 0.000 (0.000) | .827 |

| Depression × laxnessa | 0.012 (0.009) | .207 | 0.002 (0.004) | .595 |

| Depression × over/nega | 0.025 (0.037) | .491 | 0.004 (0.011) | .753 |

| Depression × warma | 0.002 (0.012) | .876 | −0.001 (0.005) | .888 |

| Education × BASC externalizing | 0.000 (0.001) | .983 | 0.000 (0.001) | .919 |

| Education × laxnessa | 0.010 (0.025) | .675 | 0.007 (0.009) | .444 |

| Education × over/nega | 0.101 (0.158) | .524 | 0.057 (0.080) | .475 |

| Education × warma | −0.008 (−0.018) | ,646 | 0.002 (0.007) | .772 |

Time 1 Externalizing Scores were entered as controls in these models.

Note. DBRS ODD = Disruptive Behavior Rating Scale-Parent Version Oppositional Defiant Disorder subscale. BASC = Behavior Assessment System for Children. Over/Neg = overreactivity/negative Affect. Models were estimated separately for each parenting variable and separately for mothers and fathers; main effect coefficients are not shown. Coefficients are unstandardized.

p < .10,

p < .05.

Does Parenting Moderate the Relation Between Early Family Adversity and ODD Symptoms?

Maternal laxness significantly moderated the relation between maternal depression and Time 4 ODD symptoms and the relation between maternal education and changes in ODD symptoms (see Table 3). However, the direction of these relations was contrary to prediction. Higher laxness was associated with a significantly weaker relation between maternal depression and Time 4 ODD symptoms, and a significantly weaker relation between maternal education and changes in ODD symptoms. When analyses were conducted separately for boys and girls using multigroup analyses, neither of these interactions were significant, but the magnitudes of the interaction coefficients were nearly identical for boys, girls, and the combined sample, and model fit was not significantly improved by allowing coefficients to differ for boys and girls compared to a model in which coefficients were set to be equal for boys and girls. No other interactions were significant for mothers or fathers and examination of boys and girls separately also yielded no significant interactions.

Are There Reciprocal Relations Between Symptoms of ODD and Parent Functioning?

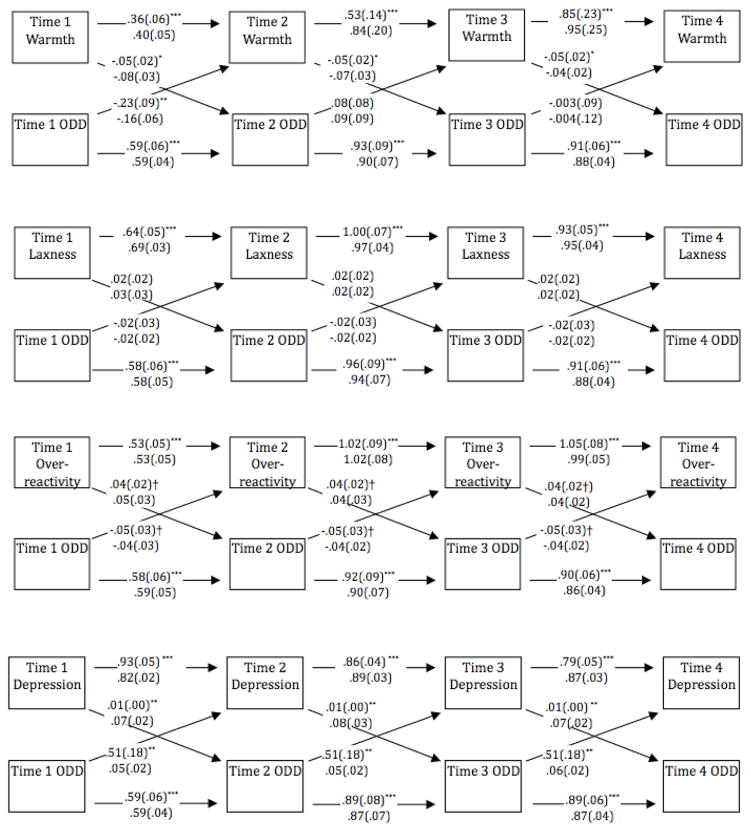

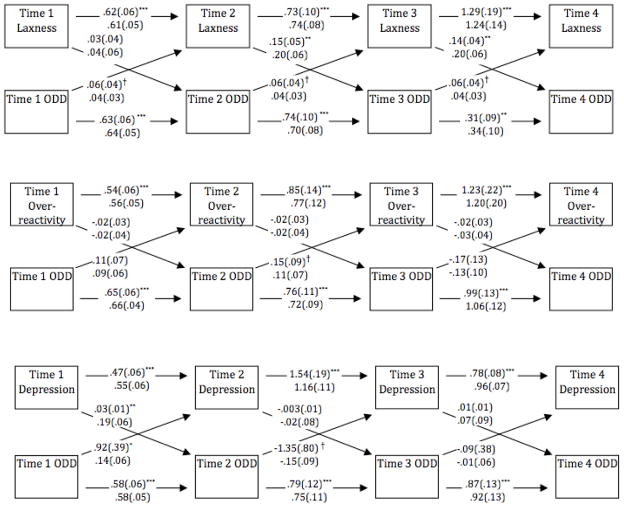

Results of the cross-lagged autoregressive models are presented in Figures 1 and 2. Correlated residuals are not shown for simplicity. For maternal depression, laxness, and overreactivity, holding cross-lagged paths equal across time did not result in significantly worse model fit, so these models were conducted with time invariant cross-lagged paths. For maternal warmth and paternal overreactivity, holding parent functioning to child ODD pathways equal across time did not result in worse model fit, but holding child ODD to parent functioning pathways equal across time did result in significantly worse model fit, so these models were estimated with only the parent to child pathways set equal across time. For paternal laxness, holding child ODD to parent functioning pathways equal across time did not result in worse model fit, but holding parent functioning to child ODD pathways equal across time did result in significantly worse model fit, so these models were conducted with only the child to parent pathways set equal across time. Finally, for paternal depression, setting cross-lagged paths equal across time resulted in significantly worse fit, so this model was conducted allowing cross-lagged paths to vary across time. Models in which paths were allowed to differ for boys and for girls did not result in significantly better model fit than models in which paths were set to be equal for boys and for girls, suggesting that cross-lagged models were not significantly different for boys and girls.

Figure 1. Cross-lagged Models for Mothers.

Note. Unstandardized coefficients are presented on the top line and standardized coefficients on the bottom line. ODD = Oppositional Defiant Disorder symptoms measured using the Disruptive Behavior Rating Scale-Parent Version

†p < .10, *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Figure 2. Cross-lagged Models for Fathers.

Note. Unstandardized coefficients are presented on the top line and standardized coefficients on the bottom line. ODD = Oppositional Defiant Disorder symptoms measured using the Disruptive Behavior Rating Scale-Parent Version.

†p < .10, *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

There was partial support for reciprocal relations between ODD symptoms and maternal warmth, overreactivity, and depression. ODD symptoms significantly predicted warmth only from Time 1 to Time 2, but warmth significantly predicted subsequent ODD symptoms at each time point. Model fit statistics suggested moderately good fit, χ2(10) = 15.91, p = .10, RMSEA = .09, CFI = .97, and SRMR = .03. For maternal overreactivity, cross-lagged paths approached significance in both directions (p = .08), and model fit was good, χ2(12) = 9.57, p = .65, RMSEA = .02, CFI = 1.00, and SRMR = .03. Maternal depression significantly predicted subsequent ODD symptoms, and ODD symptoms significantly predicted subsequent maternal depression, and model fit was good, χ2(12) = 13.15, p = .36, RMSEA = .05, CFI = .99, and SRMR = .03. There was no evidence for a reciprocal relation between maternal laxness and ODD symptoms, though model fit was good, χ2(12) = 13.07, p = .36, RMSEA = .04, CFI = 1.00, and SRMR = .03.

For fathers, there was evidence that laxness predicted subsequent ODD symptoms, with Time 2 laxness significantly predicting Time 3 ODD symptoms, and Time 3 laxness significantly predicting Time 4 ODD symptoms; ODD symptoms predicted subsequent paternal laxness at a probability level that approached significance, p = .08. Model fit for paternal laxness was good, χ2(9) = 6.64, p = .67, RMSEA = .05, CFI = .99, and SRMR = .03. There was evidence for an early reciprocal relation between paternal depression and ODD symptoms, with Time 1 depression predicting Time 2 ODD symptoms, and Time 1 ODD symptoms predicting Time 2 depression, and good model fit, χ2(8) = 14.45, p = .07, RMSEA = .06, CFI = .99, and SRMR = .02. There was no evidence of a reciprocal relation between paternal overreactivity and child ODD symptoms, χ2(10) = 32.13, p < .001, RMSEA = .10, CFI = .97, and SRMR = .05.

Discussion

The present study examined (a) the interaction between early behavior, early parenting, and early family adversity in predicting later ODD symptoms; and (b) the reciprocal relations between parent functioning and ODD symptoms across the preschool years. Based on existing theory that suggests that interactions between early child characteristics, family adversity, and parenting lead to the development of ODD (Barkley et al., 1990; Lahey & Waldman, 2003; Moffitt, 1993), it was expected that there would be a stronger relation between children’s early behavior and later ODD symptoms in the presence of more parental overreactivity/negative affect, less parental warmth, more parental laxness, and more family adversity. It was also anticipated that there would be a stronger relation between early family adversity and later ODD in the presence of more parental overreactivity/negative affect, less parental warmth, and more parental laxness. These predictions were not supported. Only maternal laxness moderated the relations between family adversity variables and ODD symptoms, and these interactions were not in the predicted direction. Greater maternal laxness was associated with a significantly weaker relation between maternal depression and age 6 ODD symptoms and with a weaker relation between maternal education and changes in ODD symptoms.

There was, however, evidence supporting reciprocal relations between ODD symptoms and some, though not all, aspects of parent functioning. The reciprocal effects were small, as is often the case in cross-lagged panels, because once autoregressive effects are controlled, there is less remaining variance to account for (Taris & Kompier, 2006). Thus, child ODD symptoms and parent functioning were primarily determined by their respective levels at the preceding time point, with reciprocal effects playing a small but significant role. The relation between maternal depression and ODD symptoms showed the clearest support for a reciprocal relation across time, with small but consistent effects at each time point. Maternal warmth and ODD symptoms predicted one another from age 3 to age 4, but effects in later years were observed only from maternal warmth to child ODD and not vice versa. Fathers’ depression at age 3 predicted children’s ODD symptoms at age 4 and children’s ODD symptoms at age 3 predicted fathers’ depression at age 4. Age 4 ODD symptoms and paternal depression in turn showed stability from age 4 to 5 and age 5 to 6, but did not show reciprocal effects after age 4. The relation between paternal laxness and ODD symptoms appeared to be driven largely by parent effects, with paternal laxness at age 4 predicting ODD symptoms at age 5 and paternal laxness at age 5 predicting ODD symptoms at age 6. Taken together, these findings provide some corroboration of previous experimental research that has demonstrated both child effects on parents (e.g., Pelham et al., 1997) and parent effects on children (Webster-Stratton & Taylor, 2001). Reciprocal relations uncovered in the present study are also consistent with previous longitudinal studies (Gross et al., 2008) that have supported reciprocal models of parent-child functioning (Bell, 1977; Patterson, 1982). These findings extend previous research by documenting how parent and child effects may vary across the preschool years, and across different types of parent functioning.

Results failed to support existing theory that argues that early child characteristics, early family adversity, and parenting interact in a particular way in the development of antisocial behavior (Lahey & Waldman, 2003). There are several possible explanations for this discrepancy. First, it is possible that this process unfolds when children are younger or older than 3 years old. The fact that Shaw et al. (1998), who studied children beginning at 1 year of age, has been one of the few studies to support interactions between parenting and early child characteristics in predicting later behavior supports the possibility that interactions may take place before 3 years of age. Second, it is possible that power was insufficient to detect significant interactions. However, the sample size in this study should have been sufficient to detect reasonable size interactions. Moreover, interaction coefficients in the present study were generally in the opposite direction than would be predicted from theory, suggesting that it is unlikely that our failure to support existing theory was due to low power. Finally, it is possible that early child characteristics, parenting, and family adversity do not interact with one another, but instead have simple effects on the development of behavior problems in young children. It may be that so few published studies have addressed these interactions because of the well-documented “file drawer” phenomenon (Dickersin, 1990). Perhaps other studies that have analyzed such interactive effects have failed to publish due to the nonsignificance of the findings. More research is needed to tease apart these possibilities.

The finding that, in the presence of less laxness, there were stronger relations between maternal depression and later ODD symptoms and between low maternal education and increases in ODD symptoms needs to be replicated, but suggests interesting possibilities. For example, it is possible that depressed mothers who are firmer and more consistent may interact more with their children than depression mothers who are lax, and there may be greater opportunity for their depression to affect their children. It is also possible that the negative effects of laxness on children leave less room for parent depression and low maternal education to affect children. If future studies replicate this finding, more research will be needed to explore these possibilities.

The findings of this study have a number of clinical implications. First, although evidence for reciprocal effects emerged for some aspects of parent functioning, autoregressive effects were much stronger than reciprocal relations, suggesting that parent and child functioning is quite stable during the preschool years. Prevention efforts are therefore key and may need to take place even before the preschool years. However, the presence of reciprocal effects--even relatively small ones--suggests that interventions that target certain aspects of parent functioning early in development may benefit from a positive cycle in which improved parent functioning leads to decreased child symptomatology which in turn may improve parent functioning. Second, these results suggest that fathers’ depression and laxness may play a role in the development of ODD, and underscore the importance of continuing to study fathers in developmental psychopathology research (Phares, Fields, Kamboukos, & Lopez, 2005). Third, evidence that paternal laxness, and to some extent maternal warmth, showed stronger parent effects than child effects, suggest that these variables may be important to target in parenting interventions. Finally, findings that both maternal and paternal depression are tied to children’s ODD symptoms early in development, suggest that it may be critical for parenting interventions to attend to parents’ emotional functioning.

The results of the present study should be interpreted in the context of its limitations. First, method variance may account for some of the observed relations in this study. In cases in which parents reported on both their own parenting/family adversity and their children’s behavior, shared method variance may have inflated the observed associations. Second, although the sample in this study was ethnically diverse, sample sizes for individual ethnic groups were too small to examine each ethnic group separately. Third, the sample included disproportionately more children with behavior problems than children without behavior problems. Although this provided the advantage of greater variability in child ODD symptoms, findings may not generalize to a more representative community sample. Fourth, reliability was low for audiotaped observations, which may have reduced power to detect effects for those variables. Fifth, assessments of fathers’ parenting were less extensive than assessments of mothers’ parenting, and there were fewer fathers than mothers, making comparisons of mothers’ and fathers’ results difficult. Sixth, mothers and fathers were analyzed separately because not all children had both parents participate, so this study was not able to examine the unique contribution of mothers’ and fathers’ functioning. Similarly, the sample size of the present study was not sufficient for testing the unique contributions of each aspect of parent functioning controlling for other aspects of parent functioning in cross-lagged models.

Despite these limitations, this study contributes to the literature in several ways. First, it is one of only a handful of longitudinal studies to test the widely posited theory that there are interactive relations between early child and family variables in predicting behavior problems. Second, this study provides some support for existing research pointing to the reciprocal relation between early child and family characteristics, and extends this literature through its focus on ODD symptoms across multiple time points during the preschool years. Finally, this study furthers our understanding of the role of fathers in the early development of ODD.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (MH60132) awarded to the first author.

Contributor Information

Elizabeth A. Harvey, Department of Psychology, University of Massachusetts Amherst

Lindsay A. Metcalfe, Department of Psychology, University of Massachusetts Amherst

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. revised. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold DS, O’Leary SG, Wolff LS, Acker MM. The parenting scale: A measure of dysfunctional parenting in discipline situations. Psychological Assessment. 1993;5:137–144. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.5.2.137. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Authors. The outcome of group parent training for families of children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and defiant/aggressive behavior. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2006;37:188–205. doi: 10.1016/j.jbtep.2005.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Disruptive Behavior Rating Scale-Parent Version (DBRS-PV): Factor analytic structure and validity among young preschool children. Journal of Attention Disorders. 2009;13:42–55. doi: 10.1177/1087054708322991. Authors. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The role of family experiences and ADHD in the early development of oppositional defiant disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011;79:784–795. doi: 10.1037/a0025672. Authors. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: A handbook for diagnosis and treatment. New York: Guilford Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA, DuPaul GJ, McMurray MB. Comprehensive evaluation of attention deficit disorder with and without hyperactivity as defined by research criteria. Journal of Consulting Clinical Psychology. 1990;58:775–789. doi: 10.1037//0022-006X.58.6.775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA, Fischer M, Edelbrock C, Smallish L. The adolescent outcome of hyperactive children diagnosed by research criteria: III. Mother-child interactions, family conflicts and maternal psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1991;32:233–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1991.tb00304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA, Murphy K. Attention-de cit hyperactivity disorder: A clinical workbook. 2. New York: Guilford; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Bell RQ. Socialization findings re-examined. In: Bell RQ, Harper RV, editors. Child effects on adults. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1977. pp. 53–84. [Google Scholar]

- Brennan PA, Grekin ER, Mednick SA. Prenatal and perinatal influences on conduct disorder and serious delinquency. In: Lahey BB, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, editors. Causes of conduct disorder and juvenile delinquency. New York: Guilford Press; 2003. pp. 319–341. [Google Scholar]

- Brunk MA, Henggeler SW. Child influences on adult controls: An experimental investigation. Developmental Psychology. 1984;20:1074–1081. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.20.6.1074. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burt SA, Krueger RF, McGue M, Iocono WG. Sources of covariation among attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, and conduct disorder: The importance of shared environment. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2001;110:516–525. doi: 10.1037//0021-843X.110.4.516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins SD, Smith CL, Gill KL, Johnson MC. Maternal interactive style across contexts: Relations to emotional, behavioral, and physiological regulation during toddlerhood. Social Development. 1998;7:350–369. doi: 10.1111/1467-9507.00072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB, Ewing LJ. Follow-up of hard-to-manage preschoolers: Adjustment at age 9 and predictors of continuing symptoms. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1990;31:871–889. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1990.tb00831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell SB, March C, Pierce E, Ewing LJ, Szumowski E. Hard to manage preschool boys: Family context and the stability of externalizing behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1991;19:301–318. doi: 10.1007/BF00911233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, Davies PT. Maternal depression and child development. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 1994;35:73–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1469–7610.1994.tb01133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham CE, Boyle MH. Preschoolers at risk for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and oppositional defiant disorder: Family, parenting, and behavioral correlates. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychiatry. 2002;30:555–569. doi: 10.1023/a:1020855429085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeKlyen M, Speltz ML, Greenberg MT. Fathering and early onset conduct problems: Positive and negative parenting, father-son attachment, and the marital context. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 1998;1:3–21. doi: 10.1023/a:1021844214633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickersin K. The existence of publication bias and risk factors for its occurrence. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1990;263:1385–1389. doi: 10.1001/jama.263.10.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downey G, Coyne JC. Children of depressed parents: An integrative review. Psychological Bulletin. 1990;108:50–76. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.108.1.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eiden RD, Edwards EP, Leonard KE. A conceptual model for the development of externalizing behavior problems among kindergarten children of alcoholic families: Role of parenting and children’s self-regulation. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43:1187–1201. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.5.1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elgar FJ, McGrath PJ, Waschbusch DA, Stewart SH, Curtis LJ. Mutual influences on maternal depression and child adjustment problems. Clinical Psychology Review. 2004;24:441–459. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankel F, Feinberg D. Social problems associated with ADHD vs. ODD in children referred for friendship problems. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 2002;33:125–146. doi: 10.1023/A:1020730224907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadow KD, Nolan EE. Differences between preschool children with ODD, ADHD, and ODD + ADHD symptoms. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2002;43:191–201. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SJ, Gotlib IH. Risk for psychopathology in the children of depressed mothers: A developmental model for understanding mechanisms of transmission. Psychological Review. 1999;106:458–490. doi: 10.1037//0033-295X.106.3.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross HE, Shaw DS, Moilanen KL, Dishion TJ, Wilson MN. Reciprocal models of child behavior and depressive symptoms in mothers and fathers in a sample of children at risk for early conduct problems. Journal of Family Psychology. 2008;22:742–751. doi: 10.1037/a0013514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heller TL, Baker BL, Henker B, Hinshaw SP. Externalizing behavior and cognitive functioning from preschool to first grade: Stability and predictors. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1996;25:376–387. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2504_3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston C, Murray C, Hinshaw SP. Responsiveness in interactions of mothers and sons with ADHD: Relations to maternal and child characteristics. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30:77–88. doi: 10.1023/A:1014235200174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan TB, Jacob RG, Pelham WE, Lang AR, Hoza B, Blumenthal JD, Gnagy EM. Depression and anxiety in parents of children with ADHD and varying levels of oppositional-defiant behaviors: Modeling relationships with family functioning. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33:169–181. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3301_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keown L, Woodward LJ. Early parenting and family relationships of preschool children with pervasive hyperactivity. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30:541–553. doi: 10.1023/A:1020803412247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Waldman ID. A developmental propensity model of the origins of conduct problems during childhood and adolescence. In: Lahey BB, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, editors. Causes of conduct disorder and juvenile delinquency. New York, NY: Guildford Press; 2003. pp. 76–117. [Google Scholar]

- Lansford JE, Criss MM, Laird RD, Shaw DS, Pettit GS, Bates JE, Dodge KA. Reciprocal relations between parents’ physical discipline and children’s externalizing behavior during middle childhood and adolescence. Development and Psychopathology. 2011;23:225–238. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loeber R, Lahey BB, Thomas C. Diagnostic conundrum of oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1991;100:379–390. doi: 10.1037//0021-843X.100.3.379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovejoy MC, Graczyk PA, O’Hare E, Neuman G. Maternal depression and parenting behavior: A metaanalytic review. Clinical Psychology Review. 2000;20:561–592. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(98)00100-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millon TM, Davis R, Millon C. Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory - III manual. 2. Minneapolis, MN: National Computer Systems, Inc; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE. Juvenile delinquency and attention deficit disorder: Boys’ developmental trajectories from age 3 to age 15. Child Development. 1990;61:893–910. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE. The neuropsychology of conduct disorder. Development and Psychopathology. 1993;5:135–151. doi: 10.1017/S0954579400004302. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 6. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2010. [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary SG, Smith Slep AM, Reid MJ. A longitudinal study of mothers’ overreactive discipline and toddlers’ externalizing behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1999;27:331–341. doi: 10.1023/A:1021919716586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardini DA, Fite P, Burke JD. Bidirectional associations between parenting practices and conduct problems in boys from childhood to adolescence: The moderating effect of age and African-American ethnicity. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:647–662. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9162-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR. A Social learning approach: III. Coercive family process. Eugene, OR: Castalia; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Pelham W, Lang AR, Atkeson B, Murphy DA, Gnagy EM, Greiner AR, Greenslade KE. Effects of deviant child behavior on parental distress and alcohol consumption in laboratory interactions. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1997;25:413–424. doi: 10.1023/A:1025789108958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfiffner LJ, McBurnett K, Rathouz PJ. Family correlates of oppositional and conduct disorders in children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2005;33:551–563. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-6737-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phares V, Fields S, Kamboukos D, Lopez E. Still looking for poppa. American Psychologist. 2005;60:735–736. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.60.7.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilowsky DJ, Wickramaratne P, Talati A, Tang M, Hughes CW, Garber J, …Weissman MM. Children of depressed mothers a year after the initiation of maternal treatment: Finding from STAR*D-Child. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;165:1136–1147. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07081286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi C, Kaiser AP. Behavior problems of preschool children from low-income families: Review of the literature. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education. 2003;23:188–216. [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CR, Kamphaus RW. Behavior Assessment System for Children. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Seipp CM, Johnston C. Mother-son interactions in families of boys with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder with and without oppositional behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2005;33:87–98. doi: 10.1007/s10802-005-0936-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Bell RQ. Developmental theories of parental contributors to antisocial behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1993;21:493–518. doi: 10.1007/BF00916316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Keenan K, Vondra JI. The developmental precursors of antisocial behavior: Ages 1–3. Developmental Psychology. 1994;30:355–364. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.30.3.355. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw DS, Winslow EB, Owens EB, Vondra JI, Cohn JF, Bell RQ. The development of early externalizing problems among children from low-income families: A transformational perspective. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1998;26:95–107. doi: 10.1023/A:1022665704584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan MJ, Watson MW. Reciprocal influences between maternal discipline techniques and aggression in children and adolescents. Aggressive Behavior. 2008;34:245–255. doi: 10.1002/ab.20241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spector A. Fatherhood and depression: A review of risks, effects, and clinical application. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2006;27:867–883. doi: 10.1080/01612840600840844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speltz ML, McClellan J, DeKlyen M, Jones K. Preschool boys with oppositional defiant disorder: Clinical presentation and diagnostic change. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1999;38:838–845. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199907000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taris TW, Kompier MAJ. Games researchers play: Extreme-groups analysis and mediation analysis in longitudinal occupational health research. Scandinavian Journal of Work, Environment & Health. 2006;32:463– 472. doi: 10.5271/sjweh.1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor E, Schachar R, Thorley G, Wieselberg M. Conduct disorder and hyperactivity: I. Separation of hyperactivity and antisocial conduct in British child psychiatric disorders. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1986;149:760–767. doi: 10.1192/bjp.149.6.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuchinich S, Bank L, Patterson GR. Parenting, peers, and the stability of antisocial behavior in preadolescent boys. Developmental Psychology. 1992;28:510–521. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.28.3.510. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Webster-Stratton C, Taylor T. Nipping early risk factors in the bud: Preventing substance abuse, delinquency, and violence in adolescence through interventions targeted at young children (0 to 8 years) Prevention Science. 2001;2:165–192. doi: 10.1023/A:1011510923900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]