Abstract

This study characterized daytime activity and apathy in patients with behavioral variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) and semantic dementia (SD) and their family caregivers. Twenty-two patient-caregiver dyads were enrolled,13 bvFTD and 9 SD.Data were collected on behaviors and movement. Patients and caregivers wore Actiwatches for 2 weeks to record activity. We predicted that bvFTD patients would show greater caregiver report of apathy and less daytime activity than patients diagnosed with SD. Findings: Patients with bvFTD spent 25% of their day immobile while patients with SD spent 16% of their day inactive. BvFTD caregivers spent 11% of their day immobile and SD caregivers 9%. Apathy was described as present in 100% of the patients with bvFTD and in all but one patient with SD, the severity of apathy was greater in bvFTD compared to SD. Apathy correlated with caregiver emotional distress in both groups. In conclusion, apathy has been defined as a condition of diminished motivation that is difficult to operationalize. Among patients with FTD, apathy was associated with lower levels of activity, greater number bouts of immobility and longer immobility bout duration. Apathy and diminished daytime activity appeared to have an impact on the caregiver. Objective measures of behavioral output may help in formulation of a more precise definition of apathy.

Keywords: frontotemporal dementia, semantic dementia, activity, caregiving, actigraphy, apathy

Introduction

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) refers to a range of neurodegenerative disorders characterized by focal atrophy of the frontal and/or anterior temporal lobes of the brain resulting in profound behavioral, cognitive, and emotional symptoms 1–3. The behavioral variant is termed bvFTD while a temporal variant is referred to as semantic dementia (SD). Both bvFTD and SD are associated with characteristic behavioral symptoms. In bvFTD these symptoms include apathy, disinhibition, aberrant motor behaviors, hyperorality or appetite disturbance, and loss of sympathy and empathy for others 3–5. Behaviorally, SD is also associated with apathy as well as mental rigidity, obsessive preoccupations, and depression 6, 7.

The neurological deterioration associated with dementia contributes to disturbances in daytime activity and disruptions have been well documented in patients with Alzheimer’s disease (AD) 8–11, dementia with Lewy bodies 12, 13, and vascular dementia 14. Daytime activity disruption has also been documented in FTD. One study of 13 patients using caregiver questionnaires reported significantly decreased morning activity compared to a normal controls and patients with AD 15. In a study of patients with advanced disease residing in a nursing home, patients with FTD showed lower mean daytime activity compared to a group of controls and patients with AD 16

In terms of daytime activity, apathy is a common symptom in FTD 3, 17, 18 and is typically rated as one of the most distressing behavioral symptoms among FTD caregivers 17, 19 Apathy incorporates cognitive, emotional, and movement features that have been historically difficult to characterize 20. Marin’s definition of apathy evolved from a core problem of motivation 21 to a reduction of goal directed behavior (lack of effort and productivity), reduction of goal directed cognition (decreased interests, decreased concern for one’s health or functional status), and emotional components (flattened affect, emotional indifference) 22. On the grounds that motivation is a difficult phenomena to assess, Levy and Dubois proposed that apathy be seen as a behavioral change from the individual’s baseline and measured as reduction in self-generated and purposeful activity 23. Others have echoed concern about the problems in assessing motivation and have suggested apathy be viewed simply as a lack of self-initiated action 20. Despite these concerns, recent consensus criteria have proposed that lack of motivation is central to characterizing apathy in AD and other neuropsychiatric conditions 24.

The purpose of this study was to characterize daytime activity using quantitative methodology in patients with mild to moderate bvFTD and SD and their family caregivers. A secondary question was whether objective data of movement could be applied toward a less ambiguous definition of apathy.

Measures

Participants

Subjects were recruited from an ongoing NIH-funded Program Project Grant (PPG) examining FTD at the University of California, San Francisco Memory and Aging Center. Consent for participation in the study on rest-activity was obtained according to approved Institutional Review Board guidelines. We enrolled 22 patient-caregiver dyads from the bvFTD and SD subgroups: 13 bvFTD and 9 SD. All patients were living at home with their spouse caregivers. Clinical diagnoses were established by consensus agreement of a panel of experts consisting of a neurologist, neuropsychologist, and a clinical nurse specialist. Neary criteria were used to establish the diagnosis of FTD 2.

Patient data included dementia severity (Clinical Dementia Rating Scale [CDR]), cognitive performance (Mini Mental State Exam [MMSE]), ratings of apathy and depression (Neuropsychiatric Inventory [NPI]), ratings of daytime sleepiness (Epworth Sleepiness Scale [ESS], and physical mobility (Barthel Index). Caregiver variables included demographic data and emotional distress of patient’s behavioral symptoms (NPI). Caregivers also maintained a “sleep diary” or record of day/night habits for both the patient and themselves that was used to validate the scoring of the actigrapy data.

The CDR is used to stage the severity of dementia 25 based on a semi-structured interview with the caregiver. A global score ranging from 0 (no dementia) to 3 (severe dementia) is computed. The MMSE is a brief, 30-point measure of cognitive function. Both instruments have good reliability and validity 26,27.

The NPI, a structured interview with established reliability and validity, assesses 12 neurobehavioral domains and the severity of caregiver’s distress. The behavioral domains include: delusions, hallucinations, agitation, depression, anxiety, euphoria, apathy, disinhibition, irritability, aberrant motor behavior, nighttime behavior, and eating/appetite. There is a yes or no screening question for each domain. If respondents answer affirmatively, the behavior is rated for frequency, severity and caregiver distress. The total score is the product of the frequency and severity. Since apathy and depression share similar features, we chose these domains to include in our analysis.

Adjunctive data is necessary in clarifying the inferences made about activity derived from actigraphy. Subjective data about patients’ daytime sleepiness (Epworth Sleepiness Scale) was collected from the caregiver. The ESS is an 8-item questionnaire measuring general level of daytime sleepiness and tendency to doze during passive activities. Scores range from 0–24, with a score of 10 or more indicating excessive sleepiness. Motor function was assessed using the Barthel Index (BI) a rating of functional independence 28. Variables assessed by the BI include bowel and bladder control, personal hygiene, transfers, walking, and stair climbing. Scores range from 5–10 per variable with 100 as the highest possible score. Higher scores reflect greater functional independence and mobility. Completion of the BI was through a semi-structured interview by the clinical nurse specialist and the caregiver.

Apparatus

Rest-activity data were collected using MiniMitter Actiwatch monitors (AW-64). Developed in the early 1970’s, actigraphy has become an accepted method for studying the rest-activity rhythm in patients with dementia 29, 30. Actigraphy is movement-based monitoring used widely in sleep and circadian rhythm research based on the premise that activity is more prominent during wake periods and less prominent during sleep 30, 31. Actigraphy provides objective movement data that it used to make inferences about a person’s activity patterns. Actiwatches are wristwatch size devices that use an accelerometer to monitor the occurrence, degree and speed of motion. A signal reflecting magnitude and duration of motion is generated, amplified and digitized by an on-board circuit. This information is stored in memory as activity counts. The Actiwatches were programmed to collect data in one-minute epochs continuously over the 2-week data collection period. Data were analyzed for daytime (from “lights on” in the morning to “lights off” at bedtime).

Daytime activity outcome variables included:

Length of the daytime interval

Average activity counts per minute

Percent immobile (percentage of time without activity during the day)

Number of hours spent immobile

Number of daytime immobility bouts

Immobility bout duration (in minutes)

Procedure

After consenting to participate in the study, patients and their primary family caregivers (all spouses) were fitted with an Actiwatch and received verbal and written instructions including research staff contact information. The actiwatches were programmed to begin monitoring activity on Monday and subjects were instructed to affix the Actiwatches to their non-dominant wrist at that time and to wear them for 2 weeks. This schedule provided consistency of activity monitoring among the study cohort. At the end of the 2-week data collection period, the watches and diaries were returned to study staff in a self-addressed, pre-paid mailer and the data was subsequently downloaded and scored.

Statistical Analysis

Actigraphy records were analyzed for both patient and caregiver dyads at the medium sensitivity setting. Areas of validated “watch off” time were deleted from analysis as well as any periods greater than 2 hours when there was no recorded activity, indicating the watch was most likely off the wrist. Records for both members of each dyad were “matched” by deleting identical periods on both records to ensure accuracy in comparison. For example if the patient had removed the watch one night, the data for both patient and caregiver were excluded on that night. To facilitate visual comparison, the actogram activity scale was calibrated to be the same for both data sets. Raw actigraphy data were subjected to a scoring algorithm in the Actiware software. Bed and rise times were interpreted by the analyst based on diary entries and the raw data. Actiware and Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) software were used for data analyses. For all variables, nonparametric independent samples were employed to compare patients with bvFTD to SD and bvFTD caregivers to SD caregivers and related samples were used to compare the bvFTD and SD patient groups with their respective caregiver groups.

Results

Means, standard deviations, and frequencies of subject baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 1. MMSE scores were significantly lower among the patients with SD compared to bvFTD (U = 26.0, p = .03). CDR scores were higher (indicating greater dementia severity) for the patients with bvFTD compared to SD (1.6 versus 1.0) (U = 29.0, p = .034).

Table 1.

Subject Baseline Characteristics

| Variables Means (standard deviations) |

FTD pts n=13 | FTD caregivers n=13 |

SD pts n= 9 | SD caregivers n=9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 61.5 (5.9) | 59.9 (9.1) | 66.2 (8.9) | 63.0 (10.8) |

| MMSE ˄ | 24.5 (3.8) | 16.4 (9.1) | ||

| CDR ∠ | 1.6 (0.6) | 1.0 (0.6) | ||

| Male | 69% | 31% | 56% | 44% |

| Barthel Index | 80.76 (22.15) | 94.44 (9.82) | ||

| ESS | 7.38 (7.44) | 6.00 (2.50) |

MMSE -Mini Mental State Exam, range 0–30;

CDR - Dementia Rating Scale, range 0–3;

ESS –Epworth Sleepiness Scale;

FTD and SD patients p = .030

FTD and SD patients p = .034

The NPI results are summarized in Table 2. Apathy was endorsed by all of bvFTD caregivers who also rated it as occurring very frequently, and by all but one SD caregiver who rated it as occurring occasionally or often. Apathy was associated with significant distress for caregivers of both patient groups (bvFTD spearman rho = .57, p < 0.05); SD spearman rho = .73, p < 0.01). There was no evidence of depression among the patients with bvFTD as rated by their caregivers. Three patients with SD were rated by their caregivers as having depression occasionally (n=1) or often (n=2).

Table 2.

Apathy and Depression Ratings

| Presence of Behavior n(%) |

Frequency Mean (sd) |

Occasionally n |

Often n |

Frequent n |

Very Frequent n |

Severity n |

Total score Mean (sd) |

Emotional distress Mean (sd) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Apathy | |||||||||

| FTD | 13 (100) | 8.3 (3.0) | - | - | - | 13 | 2.1 (0.7) | 8.3 (3.0) | 3.5 (1.1) |

| SD | 8 (88.9) | 5.5 (2.5) | 1 | - | 4 | 3 | 1.6 (0.5) | 5.5 (2.5) | 2.5 (1.3) |

| Depression | |||||||||

| FTD | 0 (0) | 0 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| SD | 3 (3) | 1.7 (0.6) | 1 | 2 | - | - | 1.0 (0) | 1.6 (0.5) | 1.7 (0.6) |

The Barthel Index scores demonstrated greater physical impairment among the patients with bvFTD compared to SD, although this reflected need for assistance with personal care and hygiene and not problems with independent movement. Only one patient with bvFTD required minor help with walking; all other patients were rated as independent in transfers, mobility, and stair climbing. Average ESS scores were 7.38 (7.44) with a range of scores from 0–23 for bvFTD and 6.00 (2.5) with a range of scores from 3.5–10 for SD. Four patients with bvFTD and one patient with SD had ESS scores greater than 10 indicating a propensity for daytime sleepiness (see Table 1).

Eight dyads had 13 days (24-hour periods) for analysis, eight dyads had between 9 and 12 days and five dyads had between 4 and 6 days of monitoring. Means and standard deviations for daytime variables were calculated and are summarized in Table 3. In all measures of daytime activity, patients with bvFTD were less mobile than their caregivers. While there were no significant differences between the patient groups, there were significant differences between the bvFTD patients and their caregivers. Mean activity counts per minute were lower for the bvFTD patients and percentage of immobile time during the daytime was higher. Patients with bvFTD were immobile 25% of the daytime hours while their caregivers were immobile 11% of the time. Thus, for the average patient with bvFTD with a daytime period length of 14.16 hours, 3.49 hours were spent immobile. Although patients with SD had similar characteristics (lower activity counts, higher percentage of time immobile) compared to their caregivers, again, these differences did not reach statistical significance.

Table 3.

Daytime variables

| Variables Mean (standard deviations) |

FTD n= 13 |

FTD CG n=13 |

SD n=9 |

SD CG n=9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Length of daytime interval in hours | 14.16 (1.6) | 15.34 (.92) | 13.85 (1.36) | 15.71 (.65) |

| Activity counts per minute | 201.07(148.95)* | 316.67 (102.45)* | 247.81 (112.07) | 332.55 (110.62) |

| Percent immobile | 24.71 (17.74)** | 11.22 (6.85)** | 15.75 (13.69) | 9.08 (5.26) |

| Number of hours spent immobile | 3.49 (.28) | 1.72 (.06) | 2.18 (.18) | 1.42 (.03) |

| Number of immobility bouts | 67.58 (31.60) | 48.88 (24.70) | 50.58 (24.63) | 41.00 (21.90) |

| Immobility bout duration (in minutes) | 2.78 (1.10) | 2.176 (0.69) | 2.37 (1.14) | 2.01 (0.43) |

Comparisons are between patient groups and their caregivers:

Wilcoxen Z = −2.621, p = .009

Wilcoxen Z = −2.830, p = .005

Correlation coefficients were calculated to examine the relationship between the patients’ total apathy score and number of immobility bouts, and total apathy score and immobility bout duration. A strong positive correlation was found (rho (11) = .756, p = .01) between apathy score and number of immobility bouts among patients with bvFTD but not SD.

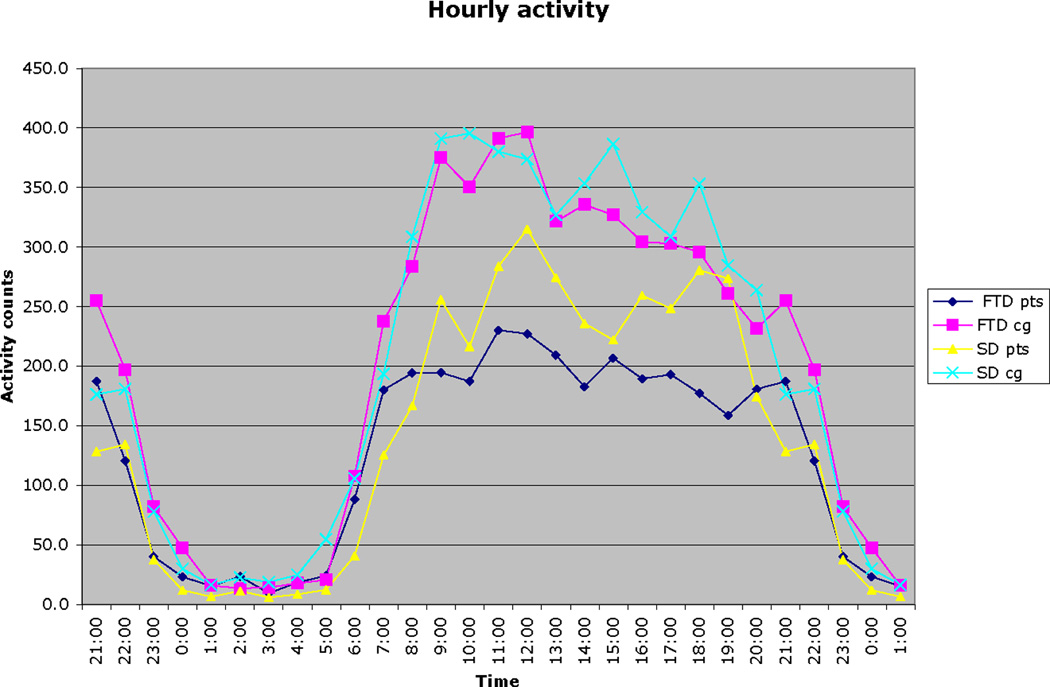

Average hourly activity scores for patients and caregivers are illustrated in Figure 1. As shown, the lowest amount of daytime activity was exhibited in the bvFTD patient group followed by the patients with SD. Both groups of caregivers showed overall greater activity than the patient groups, with the bvFTD caregivers showing less activity during the afternoon hours compared to the SD caregivers.

Figure 1.

Average hourly activity scores for patients and caregivers

Discussion

The results from this study provide objective data on daytime activity and behavior in bvFTD and SD and demonstrate that disruptions in activity are an important feature in these illnesses even in the relatively mild stages as characterized by CDR ratings and MMSE scores. In addition, these disruptions in daytime activity are associated with significant caregiver distress.

These results demonstrate that daytime activity was lower in both patient groups compared to their caregivers, but only significantly so in the bvFTD sample. This diminished activity was associated with high apathy scores (as measured by the NPI) particularly among the patients with bvFTD. Apathy incorporates cognitive, emotional, and movement features that have been historically difficult to characterize 20. Dictionaries refer to apathy as a lack of emotion, feeling, concern, or interest 32. Terms that have been used in studies of apathy include remoteness, disinterest, passivity, mental sluggishness, boredom, social withdrawal, social avoidance, lessened drive, lessened motivation, less caring, less concern, self-centeredness, loss of awareness, aspontaneity, inertia, reduction in activities of daily living, loss of interest in hobbies and leisure activities, loss of initiative, deficits in goal-directed behavior, decreased involvement in chores, decreased personal hygiene, and flattened affect. Recent consensus criteria propose that apathy be viewed as a disorder of motivation 24, yet acknowledge that “motivation” is difficult to operationalize. Since the frontal lobes are considered a primary site in the modulation of motivation, apathy in bvFTD is not a surprising finding. The results of this study help to define apathy as encompassing an observable and measurable effect on movement.

Actigraphy studies measuring movement in patients with apathy related to other brain-related conditions have yielded similar results. For example, Muller (2006) compared levels of apathy between adult patients with brain damage (n=24) and normal controls. The brain-damaged group with high apathy scores exhibited lower daytime activity, shorter episodes of daytime activity, and an increased number of naps 33. In a case report, we used actigraphy to measure activity on two occasions, one year apart in a patient with bvFTD. Activity significantly decreased by the 2nd measurement and this correlated with increased caregiver ratings of the patients’s apathy. 34.

A limitation of actigraphy is that, while it provides an objective measure of activity, it cannot define behavior. For example, periods of high activity could be due to purposeful and goal-directed behavior or due to psychomotor agitation lacking in purpose. Conversely, some purposeful activities are sedentary, for example watching television, talking on the telephone, or working at a computer. Periods of inactivity could also indicate motor impairment, depression, drowsiness, or sleeping. Thus, in an attempt to associate patient behavior with raw actigraphy data, we examined adjunctive measures in addition to employing scoring algorithms. These adjunctive measures showed no compelling evidence that low patient activity was associated with sleepiness, physical impediments, or depression. ESS scores were below 10 for the majority of patients, thus there was little evidence of patient excessive daytime sleepiness as subjectively assessed by the caregiver. Scores from the Barthel Index, while overall suggesting problems with independent function, actually support that all but one patient with bvFTD had full independent movement. There was also no evidence of depression among the patients with bvFTD as rated by their caregivers whereas three patients with SD were rated as having depression occurring either occasionally or often.

Apathy is typically measured in dementia by querying the caregiver. While caregiver reports are valuable, ratings may be biased and influenced by caregiver fatigue and burden 35. Incorporating objective measures in characterizing behavioral output among patients with dementia therefore provides useful supplementary information. While current consensus criteria recommend that apathy be conceptualized as a disorder of drive and motivation, without objective measures apathy is difficult to assess and quantify. In our study, activity counts provided objective data that was used to compare cohorts. All patients with bvFTD had apathy, and spent more time immobile than patients with SD and caregivers.

Patient behavior and activity can significantly impact family caregivers. Apathy in FTD has been associated with high levels of emotional distress for caregivers 17, 19, 36 and our data confirmed this relationship. The relationship between apathy and emotional distress was stronger among the SD caregivers compared to bvFTD caregivers. It may be that patients with SD exhibit more cognitive or emotional aspects of apathy and this is more distressful for caregivers than the movement aspect of apathy.

In addition, the lower levels of activity in patients with bvFTD appeared to be associated with lower activity in the afternoon by their caregivers. This relationship is not apparent in SD and there are several potential reasons for this finding. BvFTD caregivers may find it too difficult to engage the apathetic patient in activity, and given the need to provide patient supervision, caregivers are unable to engage in activity themselves. It is also possible that the bvFTD caregivers had diminished activity related to their own physical or emotional conditions.

Limitations

The sample size was relatively small and therefore the findings from this study may not be generalizable to other populations. We were not able to include actigraphy data from age-matched normal controls; these data would contribute to the characterization of activity in a more diverse sample. In addition, there are limitations in how apathy and depression were assessed. This study relied on caregiver ratings using the NPI. In making an assessment of apathy, caregivers are asked a stem question focused primarily on the cognitive aspect of apathy and could potentially miss identifying those patients exhibiting only emotional and movement features associated with apathy. In addition, depression is assessed by asking the caregiver if the patient appears sad or depressed, features that can be easily mistaken for apathy.

Summary

FTD is associated with early and profound changes in daytime activity. In particular, bvFTD is associated with greater apathy and lower levels of daytime activity, greater number of immobility bouts and longer immobility bout duration.. Apathy is a deficit in drive and motivation, concepts difficult to operationalize, therefore findings from this study could be applied toward a definition of apathy. Of the variables assessed, daytime immobility may be the most useful term in defining the movement aspects of apathy. In addition, activity of the patients may influence activity of the caregivers: afternoon movement was lower in the bvFTD caregiver group compared to the SD caregivers. And, while apathy was significantly associated with caregiver emotional distress for both groups, it was higher among the SD caregivers. These findings warrant further exploration with a larger sample. Choosing to objectively measure features of both the patient and their caregiver holds promise as a method for accurately assessing behavioral outputs and the functional impact of disease.

Acknowledgments

Sources of support:

The Integra Foundation Neuroscience Nursing Foundation Research Grant Program NIH 5 P01 AG019724

The John A. Hartford Center of Geriatric Excellence

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Brun A. Frontal lobe degeneration of non-Alzheimer type. I. Neuropathology. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 1987 Sep;6(3):193–208. doi: 10.1016/0167-4943(87)90021-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neary D, Snowden JS, Gustafson L, et al. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: a consensus on clinical diagnostic criteria. Neurology. 1998 Dec;51(6):1546–1554. doi: 10.1212/wnl.51.6.1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosen HJ, Allison SC, Schauer GF, Gorno-Tempini ML, Weiner MW, Miller BL. Neuroanatomical correlates of behavioural disorders in dementia. Brain. 2005 Nov;128(Pt 11):2612–2625. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller B, Darby A, Benson D, Cummings J, Miller M. Aggressive, socially disruptive and antisocial behaviour associated with fronto-temporal dementia. Br J Psychiatry. 1997 Feb;170:150–154. doi: 10.1192/bjp.170.2.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bathgate D, Snowden JS, Varma A, Blackshaw A, Neary D. Behaviour in frontotemporal dementia, Alzheimer's disease and vascular dementia. Acta Neurol Scand. 2001 Jun;103(6):367–378. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0404.2001.2000236.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bozeat S, Gregory CA, Ralph MA, Hodges JR. Which neuropsychiatric and behavioural features distinguish frontal and temporal variants of frontotemporal dementia from Alzheimer's disease? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000 Aug;69(2):178–186. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.69.2.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Seeley WW, Bauer AM, Miller BL, et al. The natural history of temporal variant frontotemporal dementia. Neurology. 2005 Apr 26;64(8):1384–1390. doi: 10.1212/01.WNL.0000158425.46019.5C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Witting W, Kwa IH, Eikelenboom P, Mirmiran M, Swaab DF. Alterations in the circadian rest-activity rhythm in aging and Alzheimer's disease. Biol Psychiatry. 1990 Mar 15;27(6):563–572. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(90)90523-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dowling GA, Hubbard EM, Mastick J, Luxenberg JS, Burr RL, Van Someren EJ. Effect of morning bright light treatment for rest-activity disruption in institutionalized patients with severe Alzheimer's disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 2005 Jun;17(2):221–236. doi: 10.1017/S1041610205001584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hatfield CF, Herbert J, van Someren EJ, Hodges JR, Hastings MH. Disrupted daily activity/rest cycles in relation to daily cortisol rhythms of home-dwelling patients with early Alzheimer's dementia. Brain. 2004 May;127(Pt 5):1061–1074. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Volicer L, Harper DG, Manning BC, Goldstein R, Satlin A. Sundowning and circadian rhythms in Alzheimer's disease. Am J Psychiatry. 2001 May;158(5):704–711. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.5.704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grace JB, Walker MP, McKeith IG. A comparison of sleep profiles in patients with dementia with lewy bodies and Alzheimer's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000 Nov;15(11):1028–1033. doi: 10.1002/1099-1166(200011)15:11<1028::aid-gps227>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harper DG, Stopa EG, McKee AC, Satlin A, Fish D, Volicer L. Dementia severity and Lewy bodies affect circadian rhythms in Alzheimer disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2004 Jul;25(6):771–781. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2003.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aharon-Peretz J, Masiah M, Pillar T, Epstein R, Tzischinksy O, Lavie P. Sleep-wake cycles in multi-infarct dementia and dementia of the Alzheimer type. Neurology. 1991;41:1616–1619. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.10.1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anderson KN, Hatfield C, Kipps C, Hastings M, Hodges JR. Disrupted sleep and circadian patterns in frontotemporal dementia. Eur J Neurol. 2009 Mar;16(3):317–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2008.02414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harper DG, Stopa EG, McKee AC, et al. Differential circadian rhythm disturbances in men with Alzheimer disease and frontotemporal degeneration. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001 Apr;58(4):353–360. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.4.353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Massimo L, Powers C, Moore P, et al. Neuroanatomy of apathy and disinhibition in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2009;27(1):96–104. doi: 10.1159/000194658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shinagawa S, Ikeda M, Fukuhara R, Tanabe H. Initial symptoms in frontotemporal dementia and semantic dementia compared with Alzheimer's disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2006;21(2):74–80. doi: 10.1159/000090139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.de Vugt ME, Riedijk SR, Aalten P, Tibben A, van Swieten JC, Verhey FR. Impact of behavioural problems on spousal caregivers: a comparison between Alzheimer's disease and frontotemporal dementia. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2006;22(1):35–41. doi: 10.1159/000093102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stuss DT, Van Reekum R, Murphy KJ. Differentiation of States and Causes of Apathy. In: Borod JC, editor. The Neuropsychology of Emotion. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000. pp. 340–363. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marin RS. Apathy: a neuropsychiatric syndrome. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1991 Summer;3(3):243–254. doi: 10.1176/jnp.3.3.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marin RS. Apathy: Concept, Syndrome, Neural Mechanisms, and Treatment. Semin Clin NeuroPsychiatry. 1996 Oct;1(4):304–314. doi: 10.1053/SCNP00100304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levy R, Dubois B. Apathy and the functional anatomy of the prefrontal cortex-basal ganglia circuits. Cereb Cortex. 2006 Jul;16(7):916–928. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robert P, Onyike CU, Leentjens AF, et al. Proposed diagnostic criteria for apathy in Alzheimer's disease and other neuropsychiatric disorders. Eur Psychiatry. 2009 Mar;24(2):98–104. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2008.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morris J. The Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993;43:2412–2414. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.11.2412-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morris J, Ernesto C, Schafer K, et al. Clinical dementia rating training and reliability in multicenter studies: the Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study experience. Neurology. 1997 Jun;48(6):1508–1510. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.6.1508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. "Mini-mental state". A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975 Nov;12(3):189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mahoney FI, Barthel DW. Functional Evaluation: the Barthel Index. Md State Med J. 1965 Feb;14:61–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Littner M, Kushida CA, Anderson WM, et al. Practice parameters for the role of actigraphy in the study of sleep and circadian rhythms: an update for 2002. Sleep. 2003 May 1;26(3):337–341. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.3.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ancoli-Israel S, Cole R, Alessi C, Chambers M, Moorcroft W, Pollak CP. The role of actigraphy in the study of sleep and circadian rhythms. Sleep. 2003 May 1;26(3):342–392. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.3.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Morgenthaler T, Alessi C, Friedman L, et al. Practice parameters for the use of actigraphy in the assessment of sleep and sleep disorders: an update for 2007. Sleep. 2007 Apr 1;30(4):519–529. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.4.519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dictionaries. The New Oxford Dictionary. 2nd ed. Oxford University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muller U, Czymmek J, Thone-Otto A, Von Cramon DY. Reduced daytime activity in patients with acquired brain damage and apathy: a study with ambulatory actigraphy. Brain Inj. 2006 Feb;20(2):157–160. doi: 10.1080/02699050500443467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Merrilees J, Hubbard E, Mastick J, Miller BL, Dowling GA. Rest-activity and behavioral disruption in a patient with frontotemporal dementia. Neurocase. 2009 Dec;15(6):515–526. doi: 10.1080/13554790903061371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCurry SM, Gibbons LE, Logsdon RG, Teri L. Anxiety and nighttime behavioral disturbances. Awakenings in patients with Alzheimer's disease. J Gerontol Nurs. 2004 Jan;30(1):12–20. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-20040101-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mourik JC, Rosso SM, Niermeijer MF, Duivenvoorden HJ, Van Swieten JC, Tibben A. Frontotemporal dementia: behavioral symptoms and caregiver distress. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2004;18(3–4):299–306. doi: 10.1159/000080123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]