Abstract

Objective

To develop and validate the HIV Self-Management Scale for women, a new measure of HIV self-management, defined as the day-to-day decisions that individuals make to manage their illness.

Methods

The development and validation of the scale was undertaken in three phases: focus groups, expert review and psychometric evaluation. Focus groups identified items describing the process and context of self-management in women living with HIV/AIDS (WLHA). Items were refined using expert review and were then administered to WLHA in two sites in the U.S. (n=260). Validity of the scale was assessed through factor analyses, model fit statistics, reliability testing, and convergent and discriminate validity.

Results

The final scale consists of 3-domains with 20 items describing the construct of HIV self-management. Daily self-management health practices, Social support and HIV self-management, and Chronicity of HIV self-management comprise the three domains. These domains explained 48.6% of the total variance in the scale. The item mean scores ranged from 1.7-2.77, and each domain demonstrated acceptable reliability (0.72-0.86) and stability (0.61-0.85).

Conclusions

Self-management is critical for WLHA, who constitute over 50% of PLWHA and have poorer health outcomes than their male counterparts. Methods to assess the self-management behavior of WLHA are needed to enhance their health and well-being. Presently no scales exist to measure HIV self-management. Our new 20-item HIV Self-Management Scale is a valid and reliable measure of HIV self-management in this population. Differences in aspects of self-management may be related to social roles and community resources and interventions targeting these factors may decrease morbidity in WLHA.

Keywords: Women, Self Care, Psychometrics, HIV, Empirical Research

Introduction

Over the past three decades, an increasing number of women have been infected with HIV1. In the United States, women account for 25% of all new HIV infections 2 and worldwide, they comprise almost one-half of all new infections 3. Women over age 50 are increasingly diagnosed with HIV and due to advances in medical therapy, women living with HIV/AIDS (WLHA) have longer life spans .4 Consequently, WLHA are increasingly diagnosed with chronic, non-AIDS defining health conditions including psychiatric, cardiovascular, gynecological, hepatic, and pulmonary disorders 5-7. These co-morbidities require many self-management behaviors similar to those required to successfully manage HIV including: adhering to medical treatment and appointments 8, monitoring symptoms 9, increasing engagement with one’s health care provider10,11, managing family responsibilities 12, managing the impact of stigma 13,14, preventing sexually transmitted diseases 15,16, and managing the interaction of all chronic diseases 17-20. Self-management work is challenging, but to women living with HIV/AIDS it can be particularly overwhelming, compared to men, due to the gender disparities in both accessibility to health care resources and health outcomes 21-24. The number and complexity of the numerous self management tasks can be daunting for WLHA and yet, this self-management behavior can help minimize the impact of these health conditions on a woman’s daily functioning25. This work suggests that self-management is important for WLHA, and in order to improve self-management behaviors in this population, clinicians and researchers working with WLHA to enhance these skills must consider the social and environmental context in which those behaviors will occur.

In health care, self-management has been defined as the day-to-day decisions and subsequent behaviors that individuals make to manage their illnesses and promote health19,26-28. Increasing the self-management skills of all persons living with HIV/AIDS may be a key way to achieve the broad aims put forth in the National HIV/AIDS Strategy for the U.S.29, especially those addressing the treatment and care of non-AIDS defining chronic co-morbidities. However, before behavioral interventions targeting HIV self-management can be developed, a valid and reliable measure of HIV self-management is needed. Several scales have been created to assess self-management for specific conditions such as asthma and diabetes 30, but none have been identified that are specific to HIV or specifically designed to assess self-management in women. Two validated scales have been developed to measure HIV self-management self-efficacy, the Perceived Medical Conditions Self-Management Scale 31 and the HIV Symptom Management Self-Efficacy for Women Scale 32. However, while self-efficacy is often considered an important mediator of behavior change, it is not the same as behavior. Self-efficacy describes one’s belief that they are able to accomplish a certain task33 whereas self-management describes the tasks one completes to manage their illnesses and promote health17. To date, no one has inductively designed and psychometrically tested a scale measuring HIV self-management behavior in adults living with HIV/AIDS. A comprehensive measure of self-management is required to precisely evaluate the different facets of self-management in adults and particularly in WLHA and to identify which aspects can be modified to decrease morbidity in WLHA. Without such a measure, it will be impossible to accurately assess the effects of new self-management interventions in this vulnerable population 34. Therefore, our objective is to report on the development and validation a new measure of HIV self-management for WLHA, the HIV Self-Management Scale.

Methods

Sample and Procedures

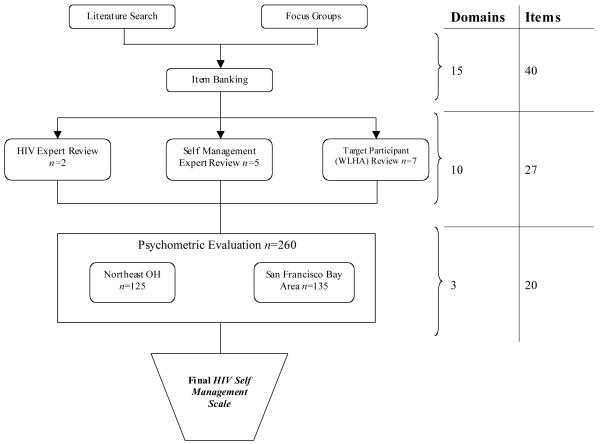

This was a prospective, mixed-method scale development study of HIV self-management in adult WLHA. We followed DeVellis’s (2003) guidelines for scale development, incorporating both qualitative and quantitative procedures 35. Accordingly, there were three main phases of scale development, (1) qualitative focus groups to generate an item pool, (2) expert review of format and item pool, and (3) psychometric evaluation of the items 35. Figure 1 describes the development of the HIV Self-Management Scale.

Figure 1. The Development of the HIV Self Management Scale.

Phase 1: Qualitative Focus Groups

Forty-eight adult (≥21 years) women living with HIV/AIDS in Ohio attended one of twelve focus groups in January-April 2010. The purpose of the focus groups was to describe qualitatively how women living with HIV/AIDS understand and practice self-management of chronic diseases. Prior to beginning the focus groups, each participant completed an informed consent document and a demographic survey. The focus groups were digitally recorded, transcribed verbatim, and a research assistant kept field notes to record key points of the discussion and important observations (nonverbal agreement, mood of the group, body language). Each participant was compensated for their time. A semi-structured focus group guide was used to facilitate the discussion on HIV self-management, which was iteratively revised after each focus group to reflect the new issues discussed. We used qualitative description and content analysis 36-38 to identify important themes and potential scale items. When possible, the participants’ actual language was used to generate possible scale items, thus enhancing item validity 35. Using these methods, we ended up with 40 possible items, representing 15 categories of HIV self-management. Additional information on the study design, sample, methods, data analysis, and results of the qualitative focus group can be found in previous publications. 39,40

Phase 2: Expert Review of Scale Format and Item Pool

For the next phase of the study, 14 HIV experts (social workers, community advocates, researchers), self-management experts (clinicians and researchers), and adult women living with HIV were recruited to evaluate the scale format and each item. To be included in this phase of the study, participants had to be adult, and either be a WLHA or someone deemed to have expertise in the area of HIV self-management. In accordance with established standards, participants were purposively selected for their clinical or scientific expertise because they were believed to have knowledge related to the practical or theoretical underpinnings of HIV self-management.41 The mean age of the experts was 43 years (+/− 8.3) and 86% (12/14) were female. All participants signed an informed consent document prior to reviewing the scale format and item pool. Participants were then given a list of each of the 40 items and asked to read, evaluate, and then rate each item on its relevance to HIV self-management, its clarity, and its uniqueness on a 10-point Likert scale (1= not relevant, clear or unique; 10= totally relevant, clear or unique).41 Participants also provided written comments about each of the items. The research team met and evaluated each of these responses, and arrived at consensus about which items to include in the psychometric evaluation of the HIV Self-Management Scale. Using these methods, we discarded 13 items which reduced the scale to 27 total items in 10 domains (Figure 1). Additionally, we modified the responses to include a 3-point Likert Scale to enhance the consistency of scoring by WLHA35. For this scaling 0 indicated the item was not applicable to the individual participant; 1 meant the individual item occurred none of time; 2 meant the item occurred some of the time; and 3 indicated the item occurred all of the time for the individual participant. With this scoring method, higher scores suggest more HIV self-management. We submitted this 27-item, unidirectional, 3-point Likert scale for psychometric evaluation.

Phase 3: Psychometric Evaluation of the Items

To evaluate the psychometric properties for the HIV Self-Management Scale we recruited 260 women from HIV Clinics and AIDS Service Organizations in Northeast Ohio and the San Francisco Bay Area in California. To be included in this sample, participants had to have a confirmed HIV diagnosis; be adult (≥21 years); identify as biologically female, and speak fluent English. Individuals were excluded if they were unable to give written informed consent or complete the survey. We chose to recruit from the San Francisco Bay Area in addition to Northeast Ohio to capture a wide range of experiences from participants. After explaining the study to potential participants, they were asked to sign an informed consent document and complete a pen and paper survey containing the HIV Self-Management Scale and related scales (described below). To assess test-retest reliability of the scale, 40% (n=108) of the participants returned two to five weeks later to complete the same survey. Each time the participant completed the survey, she was compensated with a $25 gift card. All study data were managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at University Hospitals, Case Medical Center42.

At all times the ethical implications of the study and sensitive nature of the topics discussed were at the forefront of the researcher’s actions. All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the institutional review committees for the protection of human subjects at the University Hospitals, Case Medical Center and at the University of California, San Francisco. To further protect participant privacy, a Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained from the National Institutes of Health.

Measures

Scales were chosen based on Ryan and Sawin’s Individual and Family Self-Management Theory 43 which organizes the process of self-management into contextual and process factors, and proximal and distal outcomes. These factors are particularly relevant to WLHA given the unique self-management issues they face including balancing self-management tasks with their many social roles, and completing self-management tasks in the context of fewer economic, educational, and health care resources than their male counterparts 23,24,44.

Contextual Factors

Information on the HIV-specific factors related to self-management was obtained through a demographic survey and from medical chart abstraction. The Brief Demographic Survey assessed age, education and family level of income. The Medical Information Form assessed the individual participant’s health status and health care utilization in the previous 12 months.

Access to care and transportation were assessed using Cunningham’s Access to Care Instrument45,46. The social environment was assessed using the Social Capital Scale 47,48. A description of the number of items, the reliability, and the scoring procedures of each of the scales used in this study can be found in Supplemental Table 1.

Process Factors

Self-efficacy was assessed using the abbreviated Chronic Disease Self-Efficacy Scale 49 and additional process factors, including goal setting, self-monitoring, planning and action, social support, and collaboration with the health care provider were assessed with the HIV Self-Management Instrument; the newly developed 27-item scale described in Phase 2.

Outcome Factors

The proximal outcomes of HIV specific behaviors included engagement with a health care team and HIV medication adherence. We assessed engagement with a health care team by administering the Health Care Provider Scale10. HIV medication adherence behavior was assessed using a 3-Day Visual Analog Scale 50. Additionally, reasons for non-adherence were assessed using the 9-item Revised ACTG Reasons for Missed Medications 51. The distal outcomes of quality of life and health care utilization were assessed using the HIV-Targeted Quality of Life Instrument (HAT-QOL)52 and the Medical Information Form (described above).

Data Analysis

We analyzed all demographic and medical characteristics using appropriate descriptive statistics. In the psychometric evaluation phase of the HIV Self-Management Scale we used descriptive statistics to explain each of the 27 items based on the 0-3 point Likert scale scores described above. In accordance with the acceptable standard procedures of instrument development,35 we performed exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses, obtained fit statistics, completed reliability testing, and examined convergent and discriminate validity. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) using principle axis factoring with direct oblimin rotation was conducted using all 27 items at baseline, from both sites 53. We examined the factor loadings for each item to ensure they met our inclusion criteria of a 0.40 loading, which is conventionally assumed to explain the major components of a factor 35. We deleted the poorest performing items, one at a time, and re-ran the EFA after each item deletion. We repeated this process until all items had a factor loading of approximately 0.40 and loaded on one coherent factor. We performed reliability testing using Cronbach’s alpha for internal consistency on the resulting factors, at baseline and follow up. We calculated Pearson’s correlation coefficients to analyze the convergent and discriminant validity of the scale. We used Stata version 11.2 and SPSS version 17.0 to analyze the data.

Results

Demographics and Medical Characteristics

A total of 260 WLHA completed the survey packet during the psychometric evaluation phase. The mean age was 46 (+/− 9.3) years. Most (86%) had children, were African American (66%), and single (59%). Most (79%) were unemployed, had permanent housing (82%), and had a mean annual income of $12,576 (+/− $15,001). Medically, participants’ mean year of HIV diagnosis was 1997 (+/− 7.3 years), most were currently prescribed antiretroviral therapy (ART) (80%), had an undetectable viral load (70%), and had a median CD4 cell /μ1 of 484. A range of chronic comorbidities were reported including psychiatric, cardiovascular, gynecological, hepatic, and pulmonary disorders. Additional information about the demographics and medical characteristics of participants in the psychometric evaluation phase are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic and Medical Characteristics of the Participants in the Psychometric Evaluation Phase.

| Northeast Ohio (n=125) |

San Francisco Bay Area, CA (n=135) |

Total (N=260) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency (%)a | Frequency (%)1 | Frequency (%)a | |

| Mean Age (+/−SD), years b | 45 (9.4) | 48 (8.9) | 46 (9.3) |

| Have Children | 97 (78) | 89 (66) | 186 (72) |

|

Mean number of children living with

participant (+/−SD) |

1.3 (1.2) | 0.62 (0.99) | 0.93 (1.1) |

| Race | |||

| African American | 91(73) | 78 (58) | 169 (65) |

| White/Angelo | 24 (19) | 22 (16) | 46 (18) |

| Hispanic/Latina | 13 (10) | 9 (7) | 22 (9) |

| Other | 1 (0) | 20 (15) | 21 (8) |

| Marital Status | |||

| Single | 67 (54) | 85 (63) | 152 (59) |

| Divorced | 17 (14) | 12 (9) | 29 (11) |

| Married | 21 (17) | 16 (12) | 37 (14) |

| Separated | 11 (9) | 6 (4) | 17 (7) |

| Other | 8 (6) | 8 (6) | 16 (6) |

| Education Level 3 | |||

| 11th grade or less | 52 (42) | 37 (27) | 89 (34) |

| High School or GED | 51 (41) | 52 (39) | 103 (40) |

| 2 years college/AA | 20 (16) | 28 (21) | 48 (19) |

| 4 years college/BS/BA | 5 (4) | 9 (7) | 14 (5) |

| Mean Annual Income (+/−SD) b | $10,253 (12,423) | $14,620 (16,733) | $12,576 (15,001) |

| Currently Works for Pay | 28 (22) | 26 (19) | 54 (21) |

| Has Permanent Housing c | 115 (92) | 100 (74) | 215 (83) |

| Has Health Insurance c | 118 (94) | 132 (98) | 250 (96) |

| Type of Health Insurance c | |||

| Medicaid | 87 (70) | 64 (47) | 151 (58) |

| Medicare | 18 (14) | 41 (30) | 59 (23) |

| Private, not by work | 2 (2) | 1 (0.7) | 3 (1) |

| ADAP | 4 (3) | 12 (9) | 16 (6) |

| Private, provided by work | 4 (3) | 11 (8) | 15 (6) |

| Medical Information d | |||

| Mean Year Diagnosed with HIV (+/−SD) | 1999 (7.4) | 1995 (7.4) | 1997 (7.5) |

|

Prescribed Anti-Retroviral Therapy

(ART) c |

102 (86) | 96 (74) | 198 (80) |

| Mean Year Initiated ART | 2001 (6.2) | 2001 (7.3) | 2001 (6.6) |

| Undetectable HIV Viral Load | 51 (52) | 54 (49) | 105 (50) |

|

Median HIV Viral Load for those with

detectable values/mL (IQR) |

1,747.5 (563- 9240) | 2,250 (200-10,000) | 2,027.5 (400-10,000) |

| Median CD4 cells/μ1 (IQR) | 429.5 (206-697) | 505 (266-800) | 484 (233-780) |

| Comorbidities e | |||

| Psychiatric Disorders | |||

| Depression | 46 (47) | 33 (30) | 79 (38) |

| Bipolar Disorder | 10 (10) | 6 (4) | 16 (8) |

| Anxiety | 7(7) | 2 (2) | 9 (4) |

| Cardiovascular Disorders | |||

| Hypertension | 33 (34) | 38 (34) | 71 (34) |

| Diabetes | 12(12) | 14 (13) | 26 (12) |

| High Cholesterol | 6 (6) | 6 (5) | 12 (6) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 5 (5) | 0 (0) | 5 (2) |

| Gynecological Disorders | |||

| Cervical Dysplasia | 7 (7) | 3 (3) | 10 (5) |

| HPV | 4 (4) | 2(2) | 6 (3) |

| Herpes Simplex Virus | 4 (4) | 0 (0) | 4 (2) |

| Hepatitis | |||

| Hepatitis C | 14 (14) | 31 (28) | 45 (22) |

| Hepatitis B | 0 | 3 (3) | 3 (1) |

| Pulmonary Disorders | |||

| Asthma | 15(15) | 6 (5) | 21 (10) |

| COPD | 4 (4) | 3 (3) | 7 (3) |

| Other Disorders | |||

| Arthritis | 4 (4) | 10 (9) | 14 (7) |

| Obesity | 5 (5) | 0 | 5 (2) |

| Kidney Disease | 3 (3) | 2 (2) | 5 (2) |

|

Admitted to Emergency Department in

Past 12 months |

55 (56) | 55 (50) | 110 (53) |

| Admitted to Hospital in Past 12 months | 39 (40) | 37 (33) | 76 (36) |

|

Mean Percent Missed HIV Primary Care Appointments in past 12 months (+/− SD) f |

21 (31) | 17 (26) | 19 (29) |

|

Mean medical appointments missed (+/−

SD) |

1.1 (1.9) | 1.6 (2.6) | 1.4 (2.3) |

Descriptive statistics are reported as frequency and per cent of total sample, unless otherwise noted;

Statistically significant differences between sites were found between sites and tested using a Student’s t-test at the 0.05 p-value;

Statistically significant differences between sites were found between sites and tested using either a Spearman rank correlation or chi-square at the 0.05 p-value;

Medical information was available for 98/125 (78%) of participants at the Northeast Ohio site and 111/136 (82%) of those at the San Francisco Bay area site;

Patients may have had multiple co-morbid health conditions and those reported are not mutually exclusive;

Figure calculated as the number of appointments missed/total number of the primary care appointments schedule in the previous 12 months

Psychometric and Quantitative Results

After iteratively deleting poor items, we removed 7 of the original 27 items, determining that a 3-factor solution with 20 items best described the construct of HIV self-management, and fit the psychometric data. This factor solution included factors with eigenvalues greater than 1.0 and explained 48.6% of the total variance in the scale (Table 2). The three domain solution corresponded to the process factors of Individual and Family Self-Management Theory 43.

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics and Item Factor Loadings of the HIV Self-Management Scale.

| Baseline | Factor Loading | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean +/− SD (range 0-3) |

Median | Domain 1 | Domain 2 |

Domain 3 |

|

| Domain 1: Daily Self-Management Health Practices | |||||

| 1.Staying physically active (exercising) is an important part of my HIV management strategy |

2.31 (0.76) | 2.0 | 0.12 | 0.1 | 0.65 |

| 2.I have been successful at staying physically active (walking, exercising ,stretching, weight lifting, physical work) |

2.20 (0.79) | 2.0 | 0.1 | 0.59 | |

| 3.Spirituality/Religion is my motivator to manage HIV | 2.36 (0.84) | 3.0 | −0.15 | 0.49 | |

| 4.I have been changing some aspect of my health to better manage HIV (ex: taking medication, exercising, reducing stress) |

2.41 (0.72) | 3.0 | 0.40 | ||

| 5.I have been successful at achieving my health goals | 2.21 (0.76) | 2.0 | 0.63 | ||

| 6.I modified my diet to better manage HIV (vegetables, fruits, natural ingredients) |

2.17 (0.75) | 2.0 | 0.63 | ||

| 7.Even with all of my family responsibilities I had have enough time to take care of my health needs |

2.42 (0.78) | 3.0 | 0.53 | ||

| 8.I set aside personal time to do things I enjoy | 2.30 (0.77) | 2.0 | 0.67 | ||

| 9.My job responsibilities help me to take care of my health | 1.70 (1.22) | 2.0 | −0.17 | −0.22 | 0.58 |

| 10. Educating others about HIV helps me stay in control of HIV (working as a counselor, advocating for safe sex) |

1.90 (1.14) | 2.0 | −0.21 | −0.41 | 0.41 |

| 11. When I was stressed out I did positive things to relieve the stress (exercising OR journaling OR joining a group) |

2.12 (0.84) | 2.0 | 0.59 | ||

| 12. I was able to control (or manage) HIV symptoms and medication side effects |

2.14 (0.86) | 2.0 | 0.41 | ||

| Domain Total | 2.19 (0.53) | 2.17 | |||

| Domain 2: Social Support and HIV Self-Management | |||||

| 13. When I feel overwhelmed, I find that talking to my counselor or attending support groups is very helpful. |

2.13 (0.90) | 2.0 | 0.16 | −0.73 | |

| 14. Attending support groups is an important part of HIV management strategy. |

1.95 (1.0) | 2.0 | −0.93 | ||

| 15. I have been attending support groups because I found that listening to someone’s testimony or personal story motivates me to take better care of myself. |

1.9 (1.1) | 2.0 | 0.82 | ||

| Domain Total | 2.0 (0.86) | 2.0 | |||

| Domain 3: Chronic Nature of HIV Self-Management | |||||

| 16. I have accepted that HIV is a chronic (or life-long) condition that can be managed |

2.62 (0.65) | 3.0 | 0.42 | .013 | |

| 17. Managing HIV is a number one priority for me | 2.55 (0.68) | 3.0 | 0.63 | ||

| 18. HIV has been my motivator to take better care of myself | 2.59 (0.61) | 3.0 | 0.51 | −0.13 | 0.20 |

| 19. I call to make appointments with my HIV doctor when I needed to (change in symptoms, problems with meds, new health concern) |

2.60 (0.73) | 3.0 | 0.49 | ||

| 20. My HIV doctor and I have a good relationship | 2.77 (0.60) | 3.0 | 0.63 | ||

| Domain Total | 2.64(0.43) | 2.8 | |||

Domain 1: Daily Self-Management Health Practices

The first domain, Daily Self-Management Health Practices, included 12 items (Table 3). Participants in the San Francisco Bay Area had significantly higher domain scores at baseline (t=−2.31, p=0.02). This domain corresponds to the process dimension of the Individual and Family Self-Management Theory which includes self-regulation skills and abilities (goal setting, self-monitoring, planning and action, self-evaluation, and emotional control). This factor had high internal consistency indicating acceptable levels of scale reliability. As expected, we also found evidence for convergent validity of Domain 1 with the Chronic Disease Self Efficacy Scale (r=0.34, p<0.01 at baseline; r=0.32, p<0.01 at follow-up) due the well-established relationship between chronic self-efficacy and self-management practices 19.

Table 3. Exploratory Factor Analysis Factor Summary using Principle Axis Factoring Extraction.

| Domain | Number of Items |

Item Mean Range |

Rotated Eigenvalue |

% Explained Variance |

Cronbach’s Alpha Baseline |

Cronbach’s Alpha, Follow-up (n=108) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domain 1: Daily Self-Management Health Practices |

12 | 1.7-2.42 | 5.64 | 28.2 | 0.84 | 0.85 |

| Domain 2: Social Support and HIV Self-Management |

3 | 1.90-2.13 | 2.24 | 11.2 | 0.86 | 0.83 |

| Domain 3: Chronic Nature of HIV Self-Management |

5 | 2.55-2.77 | 1.82 | 9.1 | 0.72 | 0.61 |

Domain 2: Social Support and HIV Self-Management

The second domain, Social Support and HIV Self-Management, consisted of 3 items. Participants in the San Francisco Bay Area site had significantly higher domain scores at baseline (t=−2.10, p=0.04) and follow-up (t=−2.80, p<0.01). This domain represents the social facilitation aspect of the process dimension of the Individual and Family Self-Management Theory which includes concepts of social influence, social support, and collaboration with healthcare professionals. This domain also had high internal consistency and we found evidence for convergent validity of this domain with the Social Capital Scale (r=0.18, p<0.01 at baseline; r=0.24, p=0.03 at follow-up).

Domain 3: Chronic Nature of HIV Self-Management

The final domain, Chronic Nature of HIV Self-Management, consisted of 5 items. There were no significant differences in the mean domain score between the two sites. This domain represents the knowledge and beliefs aspect of the process dimension of the Individual and Family Self-Management Theory which includes concepts of self-efficacy, outcome expectancy, and goal congruence. This factor had moderate internal consistency. We also found evidence for convergent validity of domain three with the Chronic Disease Self Efficacy Scale (r=0.26, p<0.01 at baseline; r=0.27, p<0.01 at follow-up), with our assessments of ART adherence (r=0.18, p<0.01 at baseline), and the number of years living with an HIV diagnosis (r=0.29, p<0.01 at baseline).

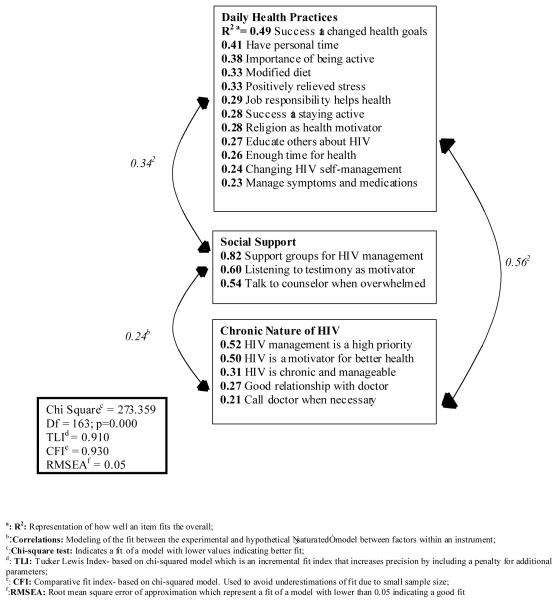

Model Fit

Fit statistics provided additional evidence that our final scale represents a good fit of the data [χ2 (163) = 273.36, p<0.01; Root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA)=.050; Tucker Lewis Index (TLI)=0.91; Confirmatory Fit Index (CFI)=0.93]. This model appears in Figure 2. The RMSEA, TLI, and the CFI approximated to the recommended cut-off range for fit indices (RMSEA <0.60; TLI & CFI >0.95). 54 Taken together, the results of our factor analyses and the corresponding fit statistics indicate that the 20-item HIV Self-Management Scale is a valid measure of the process of HIV self-management in women living with HIV/AIDS.

Figure 2. Model of the Dimensions of HIV Self-Management in Women Living with HIV/AIDS.

Discussion

Longer life expectancies of PLWH have led to an aging population living with HIV. Many WLHA will be increasingly diagnosed with additional chronic disease comorbidities and compared to men, WLHA tend to have fewer health care resources and poorer health outcomes.23,24 These comorbidities will require additional self-management work, and interventions to increase self-management behaviors will be critical to maintaining and improving the health of these women and their families. However, before assessing the efficacy of such interventions, we must first have a way to measure the process of HIV self-management. Such a scale will help us to better understand which aspects of self-management influence health outcomes and how to improve self-management behavior in this population. Similar disease-specific scales have been developed for other chronic illnesses including diabetes 55, multiple sclerosis 56, and heart failure57, but none have been developed for HIV. These scales have been used to evaluate the efficacy of clinical self-management interventions. This psychometric evaluation study provided initial evidence for the validity and reliability of a scale measuring HIV self-management in WLHA. We developed a brief, 20-item, HIV-specific scale in a generalizable sample of women living with HIV/AIDS in the U.S. and, at this time, this scale should only be considered valid in this population. However, this scale could have wider applicability, namely to WLHA in other countries with a high prevalence of HIV. To facilitate this, future research should expand this work by employing appropriate translation procedures, conducting additional psychometric testing, and reporting these findings in relevant scholarly venues. Additionally, this scale could be adapted for clinical settings to help health care providers more efficiently address self-management issues impacting the medical management goals of WLHA. The clinical application of the HIV Self-Management Scale can also help fulfill the recommendation of the National HIV/AIDS Strategy to enhance client assessment tools and measurement of health outcomes in people living with HIV with non-AIDS defining health conditions.

This valid and reliable scale captures three overarching aspects of HIV self-management that apply both to HIV itself and the other non-AIDS defining conditions that are increasingly prevalent in this population. This scale measures aspects of self-management that are commonly cited as desirable for women with chronic health conditions (including the health promotion activities of physical activity, dietary modifications, and setting health goals; engaging in social support activities; and maintaining a good relationship with one’s health care provider). It also highlights several new factors impacting the ability of a WLHA to self-manage her HIV disease, including the: [1] relationship between job and family responsibilities and self-management, [2] centrality of and difficulty obtaining personal time in this population, and [3] importance of accepting the chronic nature of HIV in order to enhance self-management behaviors. These factors can be modified through well-designed community-based and clinic-based interventions and such interventions may decrease morbidity and increase quality of life in WLHA.

It is important to note that the daily self-management health practices domain and the social support and self-management domains had significant differences between the Northeast Ohio site and the San Francisco Bay Area site. These geographic differences may indicate the context-specific nature of several of domains. Daily self-management practices and social support may depend more on the available community resources including accessibility to health care, availability of social services (case managers, housing, public transportation), and a more institutionalized acceptance of WLHA. However, the chronic nature of HIV is perhaps a more stable domain and this acceptance may not depend on the availability of social and community resources, as shown by little difference in this domain between the two sites. For example, once a woman accepts the chronic nature of her HIV disease, her priorities, motivators, and relationship with her health care provider may become more routine and less sensitive to changes in her social environment; whereas the ability of WLHA to engage in health promotion activities, to manage distressing symptoms, and to attend support groups may depend on the more flexible environmental factors described above. These factors should be further explored as they may be ideal targets of interventions to increase self-management in WLHA.

We acknowledge several limitations in our study. First, we choose to use methodology consistent with classical testing theory instead of the more recently developed item response theory. We made this choice because we believed the results of these analyses would be more familiar to scholars in the field and would enhance the usefulness of our study. However, it is possible that our findings are different than those that would have been obtained with item response analyses. Second, participants in both the focus group and expert review phases of this study were all from Northeast Ohio. This limited geographic area may represent a source of bias in our scale development, and may have led us to exclude pertinent items from the scale. This may also explain the site differences in daily self-management health practices domain and the social support and self-management domains. However, by testing the tool in San Francisco, which we believe represents a different environment than Ohio, we feel that the differences in the findings between the sites in fact strengthens the validity of the scale. Third, participants were recruited from a convenience sample and not through a random sampling of WLHA. It is possible that our participants vary systematically from the entire sample of WLHA and this may have impacted our findings and decreased the generalizability of our scale. However, the sites from which we recruited our participants are representative of the sites in which WLHA in the United States seek out care and treatment, which minimizes this risk of bias. Finally, most of our participants were prescribed ART and the self-management issues contained in our scale may not be entirely generalizable to WLHA not on or adherent to ART and those at higher risk for opportunistic infections and other complications.

In conclusion, the development and validation testing of the HIV Self-Management Scale supports the reliability and validity of this new scale. This measure will permit future researchers and clinicians to assess and integrate aspects of HIV self-management in a variety of samples and settings, to better understand how to increase these important behaviors in this population.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of the women who participated in this study, our clinical colleagues in Northeast Ohio including Jane Baum, Robert Bucklew, Barbara Gripsholver, Isabel Hilliard, Melissa Kolenz, Monique Lawson, Jason McMinn, Michele Melnick, Cheryl Streb-Baran, and Julie Ziegler, and in the San Francisco Bay Area including Roland Zepf, Lisa Dazols and all the staff at Ward 86; Edward Machtinger and the staff of the Women’s HIV Program at the University of California, San Francisco and WORLD, Oakland. We also acknowledge the contributions of Anna G. Henry, Ryan Kofman, and Ann Williams.

Footnotes

Meetings at which part of this data was presented: Preliminary findings were presented at the Clinical and Translational Research Education Meeting, Washington, DC, April 2011; Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, Baltimore, MD, November, 2011

Conflicts of Interest and Sources of Funding: This was not an industry supported study andthe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. This research was funded in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (5KL2RR024990, 1UL1 RR024989, TL1 RR024129, T32 NR007081, & P30 NR010676) in the United States. The contents of this article are solely the views of the authors and do not represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Allison R. Webel, Clinical Research Scholar, Frances Payne Bolton School of Nursing Case Western Reserve University, 10900 Euclid Avenue Cleveland, OH 44106-4904, USA.

Alice Asher, Center for AIDS Prevention Studies, University of California, San Francisco School of Nursing.

Yvette Cuca, Department of Social and Behavioral Sciences, University of California, San Francisco.

Jennifer G. Okonsky, Department of Community Health Systems, University of California, San Francisco School of Nursing.

Alphoncina Kaihura, Department of Community Health Systems, University of California, San Francisco School of Nursing.

Carol Dawson Rose, Department of Community Health Systems, University of California, San Francisco School of Nursing.

Jan E. Hanson, Department of Anthropology and Public Health, Case Western Reserve University

Robert A. Salata, Department of Medicine Division of Infectious Diseases and HIV Medicine, Case Western Reserve University.

References

- 1.Aziz M, Smith KY. Challenges and Successes in Linking HIV-Infected Women to Care in the United States. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2011 Jan 15;52(suppl 2):S231–S237. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq047. 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers, for, Disease, Control, and, Prevention. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report . Estimated numbers of cases of HIV/AIDS, by year of diagnosis and selected characteristics, 2004-2007-34 states and 5 U.S. dependent areas with confidential name-based HIV infection reporting. Vol. 19. Department of Health and Human Services Public Health Service; Atlanta, GA: [Accessed May 17, 2010]. 2010. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/reports/2007report/table1.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 3.UNAIDS . In: UNAIDS; WHO, editor. Geneva: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 4.CDC [Accessed February 7, 2012];Persons Aged 50 and Older. 2008 http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/over50/index.htm.

- 5.Phillips AN, Neaton J, Lundgren JD. The role of HIV in serious diseases other than AIDS. AIDS. 2008;22(18):2409–2418. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283174636. 2410.1097/QAD.2400b2013e3283174636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Israelski DM, Prentiss DE, Lubega S, et al. Psychiatric co-morbidity in vulnerable populations receiving primary care for HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care. 2007;19(2):220–225. doi: 10.1080/09540120600774230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cejtin HE. Gynecologic issues in the HIV-infected woman. Infectious disease clinics of North America. 2008;22(4):709–739. vii. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murphy EL, Collier AC, Kalish LA, et al. Highly Active Antiretroviral Therapy Decreases Mortality and Morbidity in Patients with Advanced HIV Disease. Annuals of Internal Medicine. 2001 Jul 3;135(1):17–26. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-1-200107030-00005. 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spirig R, Moody K, Battegay M, De Geest S. Symptom Management in HIV/AIDS: Advancing the Conceptualization. Advances in Nursing Science. 2005;28(4):333–344. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200510000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bakken S, Holzemer W, Brown M, et al. Relationships Between Perception of Engagement with Health Care Provider and Demographic Characteristics, Health Status, and Adherence to Therapeutic Regimen in Persons with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Patient Care and STDs. 2000;14(4):189–197. doi: 10.1089/108729100317795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schneider J, Kaplan S, Greenfield S, Li W, Wilson I. Better physician-patient relationships are associated with higher reported adherence to antiretroviral therapy in patients with HIV infection. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2004;19(11):1096–1103. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30418.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hackl K, Somlai A, Kelly J, Kalichman S. Women living with HIV/AIDS: The dual challenge of being a patient and caregiv. Health and Social Work. 1997;22(1):53–63. doi: 10.1093/hsw/22.1.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Clark H, Linder G, Armistead L, Austin B. Stigma, Disclosure, and Psychological Functioning Among HIV-Infected and Non-Infected African-American Women. Women & Health. 2003;38(4):57–71. doi: 10.1300/j013v38n04_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vanable P, Carey M, Blair D, Littlewood R. Impact of HIV-Related Stigma on Health Behaviors and Psychological Adjustment Among HIV-Positive Men and Women. AIDS And Behavior. 2006;10(5):473–482. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9099-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jemmott LS, Jemmott JB, III, O’Leary A. Effects on Sexual Risk Behavior and STD Rate of Brief HIV/STD Prevention Interventions for African American Women in Primary Care Settings. American Journal of Public Health. 2007 Jun 1;97(6):1034–1040. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.020271. 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marks G, Crepaz N, Senterfitt JW, Janssen RS. Meta-Analysis of High-Risk Sexual Behavior in Persons Aware and Unaware They are Infected With HIV in the United States: Implications for HIV Prevention Programs. JAIDS Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2005;39(4):446–453. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000151079.33935.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bodenheimer T, Lorig K, Holman H, Grumbach K. Patient Self-management of Chronic Disease in Primary Care. JAMA:Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002 Nov 20;288(19):2469–2475. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.19.2469. 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lorig Ritter. Plant. A disease-specific self-help program compared with a generalized chronic disease self-help program for arthritis patients. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2005;53(6):950–957. doi: 10.1002/art.21604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lorig K, Holman H. Self-management education: History, definition, outcomes, and mechanisms. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2003;26(1):1–7. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2601_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swendeman D, Ingram BL, Rotheram-Borus M. Common elements in self-management of HIV and other chronic illnesses: an integrative framework. AIDS Care. 2009;21(10):1321–1334. doi: 10.1080/09540120902803158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Webel A. Testing a peer-based symptom management intervention for women living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care. 2010;22(9):1029–1040. doi: 10.1080/09540120903214389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Webel A, Holzemer W. Positive Self-Management Program for Women Living With HIV: A Descriptive Analysis. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS care. 2009;20(6):458–467. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2009.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meditz AL, MaWhinney S, Allshouse A, et al. Sex, Race, and Geographic Region Influence Clinical Outcomes Following Primary HIV-1 Infection. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2011 Feb 15;203(4):442–451. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiq085. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stone V. HIV/AIDS in Women and Racial/Ethnic Minorities in the U.S. Current Infectious Disease Reports. 2012;14(1):53–60. doi: 10.1007/s11908-011-0226-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coleman M, Newton K. Supporting self-management in patients with chronic illness. Am Fam Physician. 2005;72(8):1503–1510. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bodenheimer T, Lorig K, Holman H, Grumbach K. Patient Self-management of Chronic Disease in Primary Care. JAMA. 2002 Nov 20;288(19):2469–2475. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.19.2469. 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mulcahy K, et al. Diabetes Self-management education: History, definition, outcomes and mechanisms. Annuals of Behavioral Medicine. 2003;26(1):1–7. doi: 10.1207/S15324796ABM2601_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuijer R, De Ridder D, Colland V, Schreurs K, Sprangers M. Effects of a short self-management intervention for patients with asthma and diabetes: Evaluating health-related quality of life usign then-test methodology. Psychology and Health. 2007;22(4):387–411. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Policy WHOoNA . National HIV/AIDS Strategy for the United States. Vol. 60. Washington, DC: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mulcahy K, Maryniuk M, Peeples M, et al. Diabetes Self-Management Education Core Outcomes Measures. The Diabetes Educator. 2003 Sep 1;29(5):768–803. doi: 10.1177/014572170302900509. 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wallston KA, Osborn CY, Wagner LJ, Hilker KA. The Perceived Medical Condition Self-Management Scale Applied to Persons with HIV/AIDS. Journal of Health Psychology. 2011;16(1):109–115. doi: 10.1177/1359105310367832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Webel AR, Okonsky J. Psychometric properties of a Symptom Management Self-Efficacy Scale for women living with HIV/AIDS. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2011;41(3):549–557. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bandura A. Social Foundation of Thoughts and Actions: A Social Cognitive Theory. Prentice Hall; Englewoods Cliffs, NJ: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Services DoHaH . AHRQ Health Services Research Projects (R01) Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; Washington, DC: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 35.DeVellis RF. Scale development: Theory and Application. 2nd ed Sage; Thousan Oaks, CA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Neergaard M, Olesen F, Andersen R, Sondergaard J. Qualitative description - the poor cousin of health research? BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2009;9(1):52. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-9-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health. 2000;23:334–340. doi: 10.1002/1098-240x(200008)23:4<334::aid-nur9>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sullivan-Bolyai S, Bova C, Harper D. Developing and refining interventions in persons with health disparities: the use of qualitative description. Nurs Outlook. 2005;53:127–133. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2005.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Webel A, Higgins P. The relationship between social roles and self-management behavior in women living with HIV/AIDS. Womens Health Issues. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2011.05.010. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Webel AR, Dolansky M, Henry A, Salata R. Women’s Self-Management of HIV: Context, Strategies and Considerations. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS care. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2011.09.002. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Davis LL. Instrument review: Getting the most from a panel of experts. Applied Nursing Research. 1992;5(4):194–197. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Paul A, Harris RT, Robert Thielke, Jonathon Payne, Nathaniel Gonzalez, Jose G, Conde R. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) - A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ryan P, Sawin KJ. The Individual and Family Self-Management Theory: Background and perspectives on context, process, and outcomes. Nursing Outlook. 2009;57(4):217–225. e216. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Webel A, Higgins P. The relationship between social roles and self-management behavior in women living with HIV/AIDS. Womens Health Issues. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cunningham WE, Ron DH, Williams KW, Beck KC, Dixon WJ, Shapiro MF. Access to Medical Care and Health-Related Quality of Life for Low-Income Persons with Symptomatic Human Immunodeficiency Virus. Medical Care. 1995;33(7):739–754. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199507000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cunningham WE, Andersen RM, Katz MH, et al. The impact of competing subsistence needs and barriers on access to medical care for persons with human immunodeficiency virus receiving care in the United States. Medical Care. 1999;37(12):1270–1281. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199912000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Onyx J, Bullen P. Measuring Social Capital in Five Communities. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science. 2000;36(1):23–42. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Webel A, Phillips J, Dawson-Rose C, et al. International AIDS Society. Rome, Italy: 2011. A Description of Social Capital in Persons Living with HIV/AIDS. Vol Abstract MOAC0105. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lorig K, Stewart A, Ritter P, González V, Laurent D, Lynch J. Outcome Measures for Health Education and other Health Care Interventions. 24-25. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks CA: 1996. pp. 41–45. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Walsh JC, Mandalia S, Gazzard BG. Responses to a 1 month self-report on adherence to antiretroviral therapy are consistent with electronic data and virological treatment outcome. Aids. 2002 Jan 25;16(2):269–277. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200201250-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chesney MA, Ickovics JR, Chambers DB, Gifford AL. Self-reported adherence to antiretroviral medications among participants in HIV clinical trials: The AACTG adherence instruments. AIDS Care. 2000;12(3):255–266. doi: 10.1080/09540120050042891. 255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Holmes WC, Shea JA. Performance of a New, HIV/AIDS-Targeted Quality of Life (HAT-QoL) Instrument in Asymptomatic Seropositive Individuals. Quality of Life Research. 1997;6(6):561–571. doi: 10.1023/a:1018464200708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jaworski B, Carey M. Development and psychometric evaluation of the self-administered questionnaire to measure knowledge and sexually transmitted diseases. AIDS And Behavior. 2007;11:557–574. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9168-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hu Lt, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6(1):1–55. 1999/01/01. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Toobert DJ, Hampson SE, Glasgow RE. The summary of diabetes self-care activities measure: results from 7 studies and a revised scale. Diabetes Care. 2000 Jul 1;23(7):943–950. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.7.943. 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bishop M, Frain M. Development and Initial Analysis of Multiple Sclerosis Self-Management Scale. International Journal of Multiple Sclerosis Care. 2007;9:35–42. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Riegel B, Carlson B, Glaser D. Development and testing of a clinical tool measuring self-management of heart failure. Heart Lung. 2000 Jan-Feb;29(1):4–15. doi: 10.1016/s0147-9563(00)90033-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.