Abstract

We present a detailed genome-scale comparative analysis of simple sequence repeats within protein coding regions among 25 insect genomes. The repetitive sequences in the coding regions primarily represented single codon repeats and codon pair repeats. The CAG triplet is highly repetitive in the coding regions of insect genomes. It is frequently paired with the synonymous codon CAA to code for polyglutamine repeats. The codon pairs that are least repetitive code for polyalanine repeats. The frequency of hexanucleotide and dinucleotide motifs of codon pair repeats are significantly (p < 0.001) different in the Drosophila species compared to the non-Drosophila species. However, the frequency of synonymous and non-synonymous codon pair repeats vary in correlated manner (r2 = 0.79) among all the species. Results further show that perfect and imperfect repeats have significant association with the trinucleotide and hexanucleotide coding repeats in most of these insects. However, only select species show significant association between the numbers of perfect/ imperfect hexamers and repeats coding for single amino acid/ amino acid pair runs. Our data further suggests that genes containing simple sequence coding repeats may be under negative selection as they tend to be poorly conserved across species. The sequences of coding repeats of orthologous genes vary according to the known phylogeny among the species. In conclusion, the study shows that simple sequence coding repeats are important features of genome diversity among insects.

Keywords: Simple sequence repeats, codon bias, codon pair repeats, insect, comparative genomics

1 Introduction

The simple sequence repeats, also well known as microsatellites, are repetitions of sequence motifs of generally 1–6 bp that are ubiquitously found in all genomes (Tautz et al. 1986). Because of wide distribution in the genomes, the simple sequence repeat sequences are also found as the most commonly shared features among eukaryotic proteins (Marcotte et al. 1999, Golding 1999, Huntley and Golding 2005). It is well known that microsatellites loci undergo rapid expansion and contraction in length (Tautz 1989, Weber and Wong 1993, Kruglyak et al. 1998, Lai and Sun, 2003). Presence of microsatellite repeats within coding sequences is known to promote rapid variation of eukaryotic proteins (Kashi and King, 2006).

Although unequal crossing-over during meiosis often generate variation of repeat length of simple sequence repeats, replication slippage is considered as the major force in the evolution of these repeat sequences (Levinson and Gutman 1987, Schlotterer and Tautz 1992, Richard and Pâques 2000). When a slippage error occurs within a microsatellite, it creates a loop in one of strands that gives rise to an insertion or a deletion in the subsequent replications depending upon if the loop is formed in the replicating strand or in the template strand respectively. This leads to increase or decrease of repeat length of microsatellites.

Apart from slippage, selection also plays a role in the variation or maintenance of repeats in the protein coding sequences (Huntley and Golding 2006). The rate of mutation of dinucleotide repeats is generally higher than the rate of mutation of trinucleotide repeats (Schlotterer and Tautz 1992). The same study (Schlotterer and Tautz 1992) also suggests that repeats containing A/T is prone to higher mutation rate than repeats containing G/C. It has also been found that longer microsatellites have a higher mutation rate than small size microsatellites (Wierdl et al. 1997, Schlötterer 1998) indicating that longer microsatellites are relatively more susceptible to potential slippage errors than short sequences. According to the proportional slippage model, microsatellites length variation is dependent on the mutation rate of the loci (Di Rienzo et al. 1994, Weber and Wong 2006) whereas the step-wise mutation model (Ohta and Kimura 1973) proposes that repeat sequences increase or decrease by one motif at a time. Furthermore, mutation bias has also been shown to affect microsatellite evolution both in prokaryotes and eukaryotes (Rubinsztein et al. 1999, Metzgar et al. 2002). Collectively, these studies have suggested that evolution of simple sequence repeats is a complex process (Ellegren 2004, Wu and Drummond 2011).

In insects, although simple sequence repeats have been extensively exploited as molecular markers in ecology and population studies (Behura 2006), the coding features of simple sequence repeats have not been well studied. Although numerous studies have been conducted in discovering microsatellites either experimentally or computationally from whole genome sequences or expressed sequence tags (ESTs) (Zane et al. 2002, Vasemägi and Nilsson 2005, Sharma et al. 2007), distribution of simple sequence repeats representing codon repeats is not well understood. Previously, a comparative analysis was performed to study the amino acid repeats among the sequenced genomes of twelve Drosophila species (Huntley and Clark 2007). But, this investigation was not oriented to address the said objectives of the present study. Moreover, genome sequences of a number of insect species are now available where no information on codon repeats is available. In this study, we present a detailed investigation on simple sequence repeats within protein coding sequences in genome-scale manner among 25 insect species.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sequence data

A total of 25 insect genomes were investigated in this study. They included twelve Drosophila species [D. melanogaster, D. simulans, D. sechellia, D. yakuba, D. erecta, D. ananassae, D. pseudoobscura, D. persimilis, D. willistoni, D. grimshawi, D. virilis, D. mojavensis], three mosquito species [Aedes aegypti (A. aegypti ), Anopheles gambiae (A. gambiae), Culex quinquefasciatus (C. quinquefasciatus)], five ant species [leaf cutter ant (Atta cephalotes), carpenter ant (Camponotus floridanus), Argentine ant (Linepithema humile), jumping ant (Harpegnathos saltator) and red harvester ant (Pogonomyrmex barbatus)] and the wasp (Nasonia vitripennis), the honey bee (Apis mellifera), the body louse (Pediculus humanus), the silk worm (Bombyx mori) and the pea aphid (Acyrthosiphon pisum). The insect names have been abbreviated as the first letter of the genus followed by three letters of the species names throughout the text and the illustrations. The annotated coding sequences (CDS) of the twelve Drosophila genes were downloaded from FlyBase (www.flybase.org). They were r1.3 version for each Drosophila (except r5.27 for D. melanogaster, r2.10 for D. pseudoobscura and r1.2 for D. virilis). The coding sequences of the three mosquitoes and the body louse were downloaded from VectorBase (http://www.vectorbase.org). The CDS of A. mellifera genes (pre-release 2), and the four ant species (Acep OGS1.2, Cflo v3.3, Hsal v3.3, Lhum OGS1.2 and Pbar OGS 1.2) were downloaded from http://hymenopteragenome.org/. The Nasonia (N. vitripennis) coding sequences (N. vitripennis_OGS_v1.2) were obtained from http://www.hgsc.bcm.tmc.edu. The aphid CDS and protein sequences were obtained from the AphidBase (http://www.aphidbase.com/aphidbase/). The silkworm CDS and protein sequences were obtained from the SilkDB (http://www.silkdb.org/silkdb/). The protein fasta files of each genome were also obtained from the respective sources.

2.2. Identification of simple sequence coding repeats

The simple sequence coding repeats were identified using a method as shown in Figure 1. First, the CDS sequences were aligned with the protein sequences using the RevTrans software (Wernersson and Pedersen 2003) to extract the codon sequences of genes in each genome. The codon sequences (5’-3’) were then subjected to SciRoKo, a simple sequence repeat (SSR) identification program (Kofler et al. 2007) to identify SSRs in the protein coding sequences. The coding motifs repeated more than 3 times were considered as repetitive in each case. The genes where one or more coding sites were ambiguous nucleotide (such as ‘N’s) were excluded from the analysis. The mono-, di-, tri- and tetra- and hexa-nucleotide SSRs were searched comprehensively to extract both perfect and imperfect repeat sequences by SciRoKo. The SciRoKo program was set to the default parameters (mismatch, fixed penalty = 5). The repeats with more than 3 consecutive mismatch sites were not allowed to report.

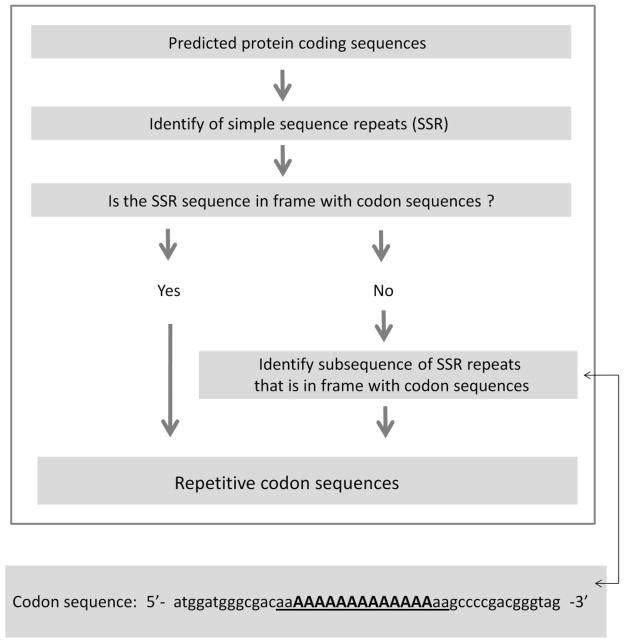

Figure 1.

Schematic description of method that was used to identify simple sequence coding repeats from whole-genome sequences. An example is provided to explain how subsequences of SSRs were determined wherein the extracted sequences were in frame with the codon sequences (bold and underlined) of the genes.

The location of SSR sequences were compared with codon sequences of genes to determine if the SSR was in frame with the coding sequence. When an SSR was in frame, the start and the end of the SSR aligned to the first and the third codon position of the gene, respectively. If they didn’t match (see Figure 1), the 5’- (and/or 3’-end) of the SSR sequences were trimmed accordingly so that the resulting subsequence of the SSR was in frame with the coding sequences. The subsequences were then extracted from the parent SSRs using the ‘seqinr’ program.

2.3. Relative codon usage of repeats

The relative usage of individual codons in the repeats was determined from the total amino acid counts corresponding to the repeats. The relative usage of codon was expressed as the proportion of observed number of codons to the expected number of codons. The expected number is estimated from total number of all synonymous codons divided by the codon degeneracy of the corresponding amino acid. The expected value of codon counts assumes no bias of codon usage i.e. all synonymous codons are equally likely to code the amino acid.

2.4. Hierarchical cluster analysis

The relative usages of individual codons among repeat regions of the 25 genomes were compared using hierarchical cluster method (average linkage) by Cluster 3.0 software (de Hoon et al. 2004). The rank order correlation based similarity matrix was used to calculate weights of both columns (codons) and rows (species) and determine correlation clusters. The self-organizing maps were viewed by TreeView program (http://www.eisenlab.org/eisen/).

2.5. Analysis of perfect and imperfect repeat sequences

The perfect and imperfect repeats were extracted from the SciRoKo output files. They were grouped separately based on motif length of SSRs (if the repeating motif is mononucleotide, dinucleotides etc.). 2 x 2 contingency tables were generated between perfect and imperfect repeats based on synonymous/ non-synonymous codon contexts of repeats. Fisher exact test was performed to determine statistical significance of association between the two factors (synonymous or non-synonymous versus perfect repeats or imperfect repeats). Similarly, the number of perfect and imperfect repeats of mononucleotides vs. trinucleotides, mononucleotides vs. hexanucleotides and trinucleotides vs. hexanucleotides were compared to know if there was a significant association between the two factors (repeat motif length types versus perfect or imperfection of the repeats). Similar tests were also performed between perfect and imperfect dinucleotides vs. perfect and imperfect hexanucleotides repeats (both coding amino acid pair repeats) to know if there was a significant association between dinucleotides/ hexanucleotides SSRs and perfect repeats/ imperfect repeats of these loci. All statistical tests were conducted using R. The p value < 0.05 was considered significant in each case.

2.6. Comparison of coding repeats of orthologous genes

To investigate sequence variation of coding repeats among orthologous genes, we compared the repeat sequences of one-to-one orthologous genes. The orthologous genes that retain one-to-one relationship among multiple species were assessed from the ‘Hierarchical Catalog of Eukaryotic Orthologs’ database (http://cegg.unige.ch/orthodb4). Note that the ant species have not been included in these analyses as their orthologs have not been annotated in the database. After identifying the one-to-one ortholog genes, it was found that some repeats were present at multiple positions within single gene. To make a conservative assessment of coding repeats sequences, we limited our analysis to repeats that are localized as single copy in the one-to-one orthologous genes. The flanking sequences of both ends of the repeats were used to generate the longest alignment of repeat sequences among the orthologous genes as described in Huntley and Clark (2007). The phylogenetic analyses were conducted using the Minimum Evolution method implemented in MEGA4 (Tamura et al. 2007). The evolutionary distances were computed using the Poisson correction method and are in the units of the number of amino acid substitutions per site.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Microsatellite sequences in the protein coding regions

The simple sequence coding repeats were identified from the protein coding regions of sequenced genomes of 25 insects using a procedure outlined in Figure 1. Results obtained from this analysis show that the number of coding repeats is widely variable among the species (Table 1). Although, the length of these repeats is generally ~ 29 bp (standard error ± 1.81), longer repeats (~ 64 bp) are observed in some species (e.g. Harpegnathos saltator ant). The analysis shows that on average ~ 26% of the annotated genes of these insects contain simple sequence coding repeats. This estimate is within the range (20 – 40%) of mammalian genes those contain coding repeats (Marcotte et al. 1999). The B. mori, A. aegypti and C. floridanus genome has less than 10% of genes those contain coding repeats whereas the D. grimshawi, D. virilis and D. mojavensis genome shows more than 50% of such genes. The density (counts/Mb of coding sequences) of coding repeats is higher in several Drosophila species compared to the non-Drosophila species indicating that coding repeats may be characteristic feature of Drosophila genomes. From the data shown in Table 1, it is also evident that within the Drosophila genus, the non-melanogaster species tend to have higher number of coding repeats than the melanogaster species. This result is in agreement with the similar observation made by Huntley and Clark (2007).

Table 1.

Count statistics of simple sequence coding repeats in the genome of 25 species. The average length shown is in basepair. Density is expressed as number of repeats per Mbp of coding sequences. Percentage is expressed as amount (in bp) of repeats to the total amount of coding sequences in the genome.

| Species | Counts | Avr. Length | Density | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aaeg | 818 | 19.94 | 34.49 | 0.069 |

| Acep | 1918 | 41.12 | 98.18 | 0.404 |

| Agam | 5582 | 23.75 | 246.28 | 0.585 |

| Amel | 1817 | 27.36 | 99.7 | 0.273 |

| Apis | 4283 | 23.14 | 120.08 | 0.278 |

| Bmor | 694 | 24.86 | 38.76 | 0.096 |

| Cflo | 1344 | 39.54 | 64.77 | 0.256 |

| Cqui | 2976 | 23.07 | 120.1 | 0.277 |

| Dana | 1540 | 23.44 | 136.26 | 0.319 |

| Dere | 4184 | 26.94 | 190.98 | 0.515 |

| Dgri | 9392 | 25.99 | 421.01 | 1.094 |

| Dmel | 6923 | 25.04 | 156.66 | 0.392 |

| Dmoj | 9056 | 30.7 | 418.61 | 1.285 |

| Dper | 6344 | 24.96 | 292.58 | 0.730 |

| Dpse | 7010 | 24.99 | 294.97 | 0.737 |

| Dsec | 2811 | 24.79 | 130.69 | 0.324 |

| Dsim | 2586 | 24.53 | 135.89 | 0.333 |

| Dvir | 8942 | 27.51 | 411.18 | 1.131 |

| Dwil | 7303 | 23.67 | 321.81 | 0.762 |

| Dyak | 3983 | 26.51 | 175.82 | 0.466 |

| Hsal | 3832 | 63.62 | 187.71 | 1.194 |

| Lhum | 2468 | 33.58 | 120.3 | 0.404 |

| Nvit | 2836 | 25.21 | 96.19 | 0.242 |

| Pbar | 3042 | 37.9 | 148.04 | 0.561 |

| Phum | 4232 | 22.31 | 254.26 | 0.567 |

3.2. Microsatellites and codon repeats

The simple sequence repeats within protein coding regions mostly represent single codon repeats (SCRs which are trinucleotide SSRs) and, to a lesser extent, codon pair repeats (CPRs which are hexanucleotide SSRs) (Table 2). The excess of SCRs over CPRs is most likely linked to efficiency of translational process. For example, CPRs with one rare codon and the other optimal codon as the repetitive motif can be less advantageous for translation compared to SCRs where the repetitive motif is an optimal codon. While translation of single codon repeats requires only one tRNA molecule, synthesis of two tRNAs is required in an alternate manner to translate codon pair repeats. This hypothesis is also supported from earlier works that reveal patterns of evolutionary co-adaptation between synonymous codons and their corresponding isoacceptor tRNA genes (Buchan et al. 2006, Behura et al. 2010, Behura and Severson 2011). While SCRs strictly code of single amino acid repeats (SARs), CPRs code either SARs or amino acid pair repeats (APRs) (Figure 2). This is because, in CPRs, the codon pairs are either synonymous or non-synonymous to each other. The trinucleotide microsatellites predominantly represent SARs, as also observed in other species (Sutherland and Richards 1995, Katti et al. 2001). The mononucleotide and hexanucleotide motifs also code for SARs albeit with lower frequency (Table 3).

Table 2.

Total counts and amount (bp) of coding microsatellites representing single codon repeats (SCRs) or codon pair repeats (CPRs) in different species.

| Species | SCR counts | SCR amount (bp) | CPR counts | CPR amount (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aaeg | 665 | 10662 | 117 | 1698 |

| Acep | 1350 | 56526 | 341 | 8376 |

| Agam | 5126 | 100791 | 391 | 7314 |

| Amel | 1316 | 31674 | 352 | 7446 |

| Apis | 2771 | 56949 | 711 | 12162 |

| Bmor | 377 | 6489 | 165 | 3576 |

| Cflo | 804 | 16368 | 278 | 6000 |

| Cqui | 2601 | 41181 | 250 | 11988 |

| Dana | 1190 | 22989 | 328 | 5346 |

| Dere | 3010 | 69660 | 1103 | 20904 |

| Dgri | 7761 | 169089 | 1530 | 29616 |

| Dmel | 5992 | 127779 | 870 | 14118 |

| Dmoj | 6923 | 162243 | 2037 | 69018 |

| Dper | 4082 | 84936 | 2117 | 37272 |

| Dpse | 4824 | 100191 | 2076 | 37050 |

| Dsec | 2310 | 48189 | 434 | 7932 |

| Dsim | 2077 | 43422 | 421 | 7026 |

| Dvir | 7374 | 163050 | 1499 | 39810 |

| Dwil | 6243 | 121713 | 992 | 16908 |

| Dyak | 2938 | 65790 | 977 | 19176 |

| Hsal | 2021 | 62445 | 581 | 17112 |

| Lhum | 1598 | 47262 | 622 | 19188 |

| Nvit | 2121 | 43410 | 558 | 13470 |

| Pbar | 2021 | 75096 | 666 | 17706 |

| Phum | 3687 | 68298 | 331 | 5328 |

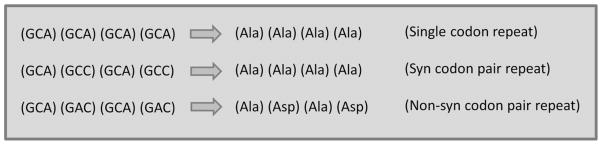

Figure 2.

Illustrative examples of single codon and codon pair repeats. Single codon repeats code for single amino acid repeats. Single amino acid repeats can also be coded by repeats of synonymous codon pairs. Non-synonymous codon pairs code for repeats of amino acid pairs.

Table 3.

Distribution of mono-, di-, tri- and hexa-nucleotide microsatellite motifs in single amino acid repeats (SARs) and amino acid pair repeats (APRs) of different insect genomes.

| Species | Mononucleotide SARs | Trinucleotide SARs | Hexanucleotide SARs | Dinucelotide APRs | Hexanucleotide APRs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aaeg | 2 | 663 | 50 | 3 | 64 |

| Acep | 3 | 1347 | 79 | 142 | 120 |

| Agam | 4 | 5122 | 146 | 72 | 173 |

| Amel | 93 | 1223 | 67 | 107 | 178 |

| Apis | 327 | 2444 | 97 | 282 | 332 |

| Bmor | 2 | 375 | 34 | 6 | 125 |

| Cflo | 7 | 797 | 64 | 74 | 140 |

| Cqui | 7 | 2594 | 49 | 21 | 180 |

| Dana | 1 | 1189 | 55 | 1 | 272 |

| Dere | 2 | 3008 | 133 | 10 | 960 |

| Dgri | 2 | 7759 | 290 | 40 | 1200 |

| Dmel | 1 | 5991 | 147 | 16 | 707 |

| Dmoj | 4 | 6919 | 366 | 23 | 1648 |

| Dper | 5 | 4077 | 252 | 27 | 1838 |

| Dpse | 0 | 4824 | 281 | 24 | 1771 |

| Dsec | 4 | 2306 | 60 | 7 | 367 |

| Dsim | 2 | 2075 | 53 | 11 | 357 |

| Dvir | 2 | 7372 | 273 | 18 | 1208 |

| Dwil | 2 | 6241 | 247 | 14 | 731 |

| Dyak | 2 | 2936 | 139 | 8 | 830 |

| Hsal | 14 | 2007 | 101 | 183 | 297 |

| Lhum | 29 | 1569 | 59 | 395 | 168 |

| Nvit | 39 | 2082 | 83 | 247 | 228 |

| Pbar | 39 | 1982 | 99 | 339 | 228 |

| Phum | 232 | 3455 | 54 | 30 | 247 |

APRs are encoded by either hexanucleotide or dinucleotide SSRs. Data in Table 3 shows that hexanucleotide repeats that code for SARs are relatively less frequent than the hexanucleotide repeats that code for APRs in most of the insects. This suggests that only a small fraction of codon pair repeats contributes to single amino acid repeats whereas majority of the codon pair repeats code for repeats of amino acid pairs. However, our analysis further reveals that a significant correlation (Spearman correlation p < 0.05; r2 = 0.79) exists between the number of hexanucleotide repeats coding for either SARs or APRs among the 25 insects. Because, the codon pairs in hexanucleotide SSRs may be either synonymous or non-synonymous to each other, the above result suggests that synonymous and non-synonymous codon contexts have similar representation to the simple sequence repeats coding for SARs and APRs across genomes.

3.2. Amino acids encoded by coding microsatellites

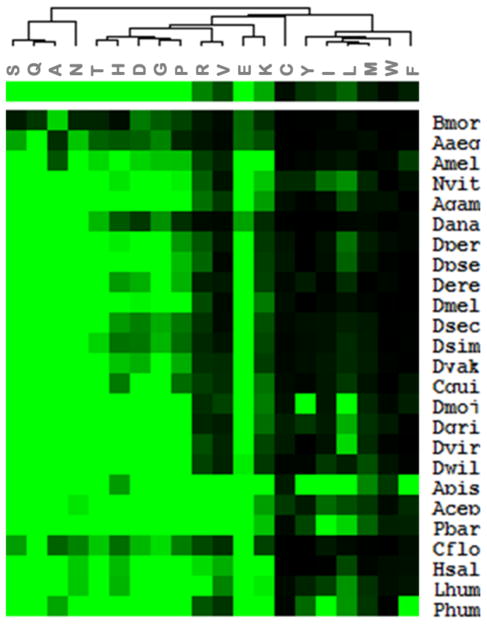

Hierarchical cluster analysis was conducted based on the amount of coding microsatellites corresponding to each of the 20 standard amino acids among the 25 genomes (Figure 3). It shows that all amino acids are not equally represented by the simple sequence coding repeats. For example, amino acids Ser, Gln, Ala and Asn are represented relatively more by coding repeats compared to Tyr, Ile, Leu, Met, Pro and Phe in all the insects. We also find that specific trinucleotide motifs are highly repetitive across all the 25 insect genomes (Table 4). The CAG codon (coding for polyglutamine repeats) is highly repetitive across the genomes. The CAG motif forms codon context with CAA (synonymous codon of CAG) resulting in repetitions of CAACAG coding polyglutamine repeats in majority of these insects (Supplementary Table 1). On the other hand, the GCAGCG sequences represent the least repetitive coding hexamers (coding polyalanine repeats) in majority of these insects suggesting that the GCAGCG synonymous codon context is strongly avoided in coding polyalanine repeats. The other highly and lowly repetitive codon sequences of these insects are listed in Table 4.

Figure 3.

Variation in the representation of amino acids by the simple sequence repeats among the 25 insects based on hierarchical cluster analysis. The green color represents high and black color shows low representation. The insect names (4 letters) are shown as rows and the amino acids (single letter abbreviations) are shown as columns. The clustering tree among the amino acids is also shown.

Table 4.

Coding sequences that are highly and lowly repetitive in different species. The amount of each repeat sequence (total bp) is also shown.

| Species | Highly repetitive | Amount (bp)** | Lowly repetitive | Amount (bp)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aaeg | CAG (Gln) | 1824 | CCG (Pro) | 12 |

| Acep | GAC (Asp) | 5730 | CTT (Leu) | 12 |

| Agam | CAG (Gln) | 40983 | AAA (Lys) | 12 |

| Amel | CAG (Gln) | 5259 | ATA (Ile) | 12 |

| Apis | CAA (Gln) | 4548 | CTA (Leu) | 12 |

| Bmor | GCC (Ala) | 966 | TGC (Cys) | 12 |

| Cflo | CAG (Gln) | 2169 | TTT (Phe) | 12 |

| Cqui | CAG (Gln) | 11907 | TTG (Leu) | 12 |

| Dana | CAG (Gln) | 10431 | CGC (Arg) | 12 |

| Dere | CAG (Gln) | 38550 | CGT (Arg) | 12 |

| Dgri | CAG (Gln) | 54909 | AGA (Arg) | 12 |

| Dmel | CAG (Gln) | 67767 | TTA (Leu) | 12 |

| Dmoj | CAG (Gln) | 64194 | TAT (Tyr) | 12 |

| Dper | CAG (Gln) | 39810 | AAA (Lys) | 12 |

| Dpse | CAG (Gln) | 48606 | TCT (Ser) | 12 |

| Dsec | CAG (Gln) | 24975 | AGT (Ser) | 12 |

| Dsim | CAG (Gln) | 23256 | CGC (Arg) | 12 |

| Dvir | CAG (Gln) | 55740 | ACT (Thr) | 21 |

| Dwil | CAG (Gln) | 24648 | CTC (Leu) | 12 |

| Dyak | CAG (Gln) | 32775 | CGT (Arg) | 12 |

| Hsal | CAG (Gln) | 10170 | TGC (Cys) | 12 |

| Lhum | CAG (Gln) | 9795 | TTG (Leu) | 15 |

| Nvit | CAG (Gln) | 13938 | CGT (Arg) | 12 |

| Pbar | GAC (Asp) | 6858 | TGT (Cys) | 30 |

| Phum | AAT (Asn) | 15540 | CGT (Arg) | 18 |

Amount of highly repetitive motif;

amount of lowly repetitive motif

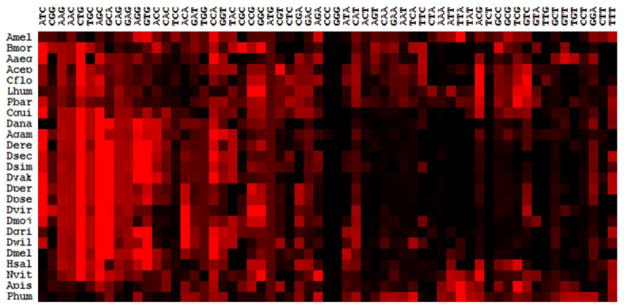

Our results further reveal that specific codons are highly preferred by all the 25 insects to code specific amino acid repeats. This was evident from hierarchal cluster analysis of RSCU values (measure of biased usage of codons) of individual codons among the 25 genomes (Figure 4). Based on results of this analysis, the (CTG)n repeats are most preferred sequences for coding polylysine repeats. On the other hand, the (GGG)n and (CCC)n repeats are strongly avoided across species while coding polyglycine and polyproline repeats respectively. Such preference/ non-preference of repeat sequences may be linked to efficiency and accuracy of coding sequences (referred to as ‘translational selection’) to synthesize the amino acid runs.

Figure 4.

Variation of relative synonymous codon usages among the 25 insects. The insect names (4 letters) are shown in rows and codons are shown in columns.

The amino acid residues encoded by coding microsatellites of these insects are generally associated with negative hydrophobicity index (ranging from −2.4 to −1.7) (data not shown) suggesting that these amino acids hydrophilic in nature. In general, hydrophobic amino acids are more likely to be localized in the protein interiors whereas hydrophilic amino acids are localized on the outer surface to interact with the aqueous environment. Because the repetitive amino acids are mostly associated with negative hydrophobicity in these insects, it is likely that the repeat amino acid sequences may be associated with the outer surface (possibly with the hydrophilic head structures) of the encoded proteins. A possible explanation could be that, because of rapid changes in the microsatellite repeats (either by replication slippage or by expansion/contraction of repeat lengths); these hydrophilic residues may undergo rapid adaptation of the outer surface of the proteins to the aqueous environment. In support to this, the study by Katti et al. (2001) also suggests that codon repeats representing runs of hydrophilic amino acids are more prone to length variation than codon repeats representing runs of hydrophobic amino acids.

Furthermore, there are some indications that genes containing repetitive coding microsatellites are associated with specific functions. Based on gene ontologies of D. melanogaster genes, genes containing coding microsatellites are mostly associated with development, transcription, transport and proteolysis (data not shown), an observation which is consistent to other earlier reports (Karlin and Burge 1996, Huntley and Golding 2004, Huntley and Clark 2007, Behura et al. 2011).

3.3. Perfect vs. imperfect coding repeats

The simple sequence coding repeats in each genome consisted of both perfect and imperfect motifs (Supplementary Figure 1). On average, the lengths of coding microsatellites with perfect motif repeats are of 15 (± 0.6) bp whereas those of imperfect motif repeats are 36 (± 2.4) bp. The length of microsatellite motif seems to have an association with the perfect or imperfect repetition of the motif (Supplementary Table 2). It is found that trinucleotide and hexanucleotide coding repeats show significant associations between perfect and imperfect motif sequences, almost in all the insects (Table 5). Also, trinucleotide and hexanucleotide repeats are largely associated with coding SARs and APRs of the encoded proteins. The perfect and imperfect microsatellite repeats coding for APRs has no relationship with the synonymous or non-synonymous nature of the codons within the hexamer repeats (Table 6). This suggests that perfect and imperfect codon pair repeats represent single amino acid repeats (synonymous pairs) or amino acid pair repeats (non-synonymous pairs) without any bias. Although this pattern was observed for majority of the insects, significant association was observed between repeat type (perfect or imperfect) and nature of the repeating codon pairs (synonymous or non-synonymous) in some insects such as Drosophila erecta, Linepithema humile and Pediculus humanus..

Table 5.

Significant association of perfect/ imperfect sequences of different types of coding microsatellites (compared in pair-wide manner).

| Species | Mononucleotides vs. Trinucleotides | Trinucleotides vs. Hexanucleotides | Mononucleotides vs. Hexanucleotides | Dinucleotides vs. Hexanucleotides |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aaeg | − | − | − | − |

| Acep | − | + | − | - |

| Agam | − | + | − | + |

| Amel | − | + | − | + |

| Apis | + | + | + | + |

| Bmor | − | − | − | − |

| Cflo | − | + | − | + |

| Cqui | − | − | − | − |

| Dana | − | − | − | − |

| Dere | − | + | − | − |

| Dgri | − | + | − | − |

| Dmel | − | + | − | − |

| Dmoj | − | − | − | − |

| Dper | − | + | − | − |

| Dpse | − | + | − | − |

| Dsec | − | + | − | − |

| Dsim | − | + | − | − |

| Dvir | − | + | − | − |

| Dwil | − | − | − | − |

| Dyak | − | + | − | − |

| Hsal | − | − | + | − |

| Lhum | + | + | − | + |

| Nvit | + | − | + | − |

| Pbar | + | + | + | − |

| Phum | + | − | + | − |

The + sign indicates statistical significant (p < 0.05) association of SSR features (perfect vs. imperfect SSRs compared in pairs) in the genome. The entries with − sign indicates non-significant association.

Table 6.

Comparison of perfect /imperfect codon pair repeats that are either synonymous or non-synonymous to each other.

| Species | SYNs-perfect | NonSYNs-perfect | SYNs-Imperfect | NonSYNs-Imperfect | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aaeg | 39 | 59 | 11 | 8 | 0.205 |

| Acep | 55 | 155 | 24 | 107 | 0.113 |

| Agam | 107 | 169 | 39 | 76 | 0.422 |

| Amel | 45 | 188 | 22 | 97 | 0.887 |

| Apis | 74 | 438 | 23 | 176 | 0.333 |

| Bmor | 26 | 87 | 8 | 44 | 0.305 |

| Cflo | 54 | 155 | 10 | 59 | 0.069 |

| Cqui | 40 | 152 | 9 | 49 | 0.452 |

| Dana | 34 | 203 | 21 | 70 | 0.069 |

| Dere | 97 | 620 | 36 | 350 | 0.042 |

| Dgri | 188 | 758 | 102 | 482 | 0.254 |

| Dmel | 101 | 534 | 46 | 189 | 0.221 |

| Dmoj | 199 | 964 | 167 | 707 | 0.268 |

| Dper | 162 | 1200 | 90 | 665 | 1 |

| Dpse | 171 | 1155 | 110 | 640 | 0.257 |

| Dsec | 44 | 242 | 16 | 132 | 0.240 |

| Dsim | 38 | 248 | 15 | 120 | 0.637 |

| Dvir | 172 | 785 | 101 | 441 | 0.781 |

| Dwil | 154 | 512 | 93 | 233 | 0.072 |

| Dyak | 98 | 544 | 41 | 294 | 0.211 |

| Hsal | 59 | 296 | 42 | 184 | 0.575 |

| Lhum | 49 | 266 | 10 | 297 | 0.000 |

| Nvit | 60 | 345 | 23 | 130 | 1 |

| Pbar | 56 | 332 | 43 | 235 | 0.741 |

| Phum | 34 | 216 | 20 | 61 | 0.024 |

The Fisher exact test p values are shown for each genome (those in bold shows significant p value < 0.05).

3.4. Comparison of coding repeats among orthologous genes

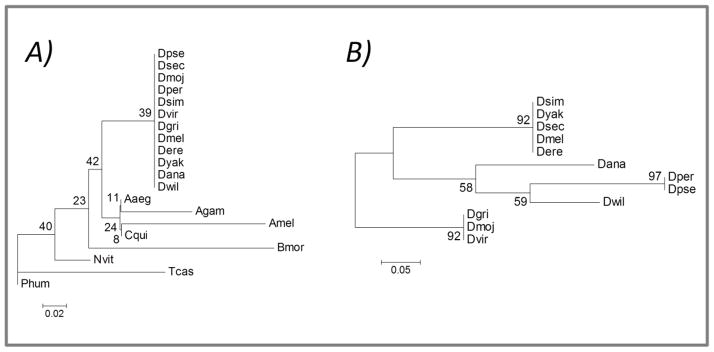

We further investigated if the repeat-containing genes were common among related species of these insects. It was found that overwhelming majorities (87%) of these genes were species-specific and had no orthologous relationship with any other species. If there is a selection constraint on repeat containing genes for which we observe such lack of orthology across species remains to be investigated. Among all the identifiable orthologous genes (including genes that are orthologous only between two species), nearly two-thirds of orthologs contain multiple repeats in each gene. A total of 4,164 genes were identified as single repeat containing orthologous genes. However, many of these genes are orthologous only between two species. Only 823 genes of these were found common among three or more species. A total of 41 repeat-containing genes were identified from the above 823 genes wherein the genes were orthologous among more than eight species (Supplementary Table 3). The sequences of coding repeats of these 41 orthologous gene sets were further analyzed. Phylogenetic analysis of these sequences clearly shows that the repeat variation is largely according to the known phylogeny of the species (Figure 5) suggesting that coding microsatellites may have evolved in species specific manner among the insects.

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic relationship of coding repeats among orthologous genes. A). Phylogeny of coding sequences of orthologous genes in different orders of insects. B). Phylogeny of coding sequences of orthologous genes within the genus Drosophila. The trees are inferred based on minimum evolution method. The percentages of replicated trees in which the associated species clustered together in the bootstrap test (1000 replicates) are shown next to the branches. The tree is drawn to scale (shown below the tree), with branch lengths in the same units as those of the evolutionary distances used to infer the phylogenetic tree.

4. Conclusions

The results of this study provide useful insights on structure and distribution of simple sequence coding repeats as well as the patterns of perfect and imperfect sequences of these repeats among diverse insect species. The study reveals that coding repeats are important features of genome diversity among insects.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Simple sequence coding repeats among 25 insect species are analyzed.

Trinucleotide repeats are predominant in the coding sequences.

Synonymous and non-synonymous codon pair repeats vary in correlated manner across species.

Exceptionally high frequency of codon pair repeats in Drosophila species.

The sequences of coding repeats of orthologous genes vary according to the known phylogeny among the species

Acknowledgments

The work was supported in part by grant RO1-AI079125-A1 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health. The authors would like to thank Dr. John Tan for useful suggestions that helped improve an initial draft of this manuscript and also Becky deBruyn and Diane Lovin for proof-reading the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- SCR

single codon repeats

- CPR

codon pair repeats

- SAR

single amino acid repeats

- APR

amino acid pair repeats

- RSCU

relative synonymous codon usage

- Syn

synonymous

- Non-syn

non-synonymous

- Dmel

Drosophila melanogaster

- Dsim

Drosophila simulans

- Dsec

Drosophila sechellia

- Dyak

Drosophila yakuba

- Dere

Drosophila erecta

- Dana

Drosophila ananassae

- Dpse

Drosophila pseudoobscura

- Dper

Drosophila persimilis

- Dwil

Drosophila willistoni

- Dgri

Drosophila grimshawi

- Dvil

Drosophila virilis

- Dmoj

Drosophila mojavensis

- Aaeg

Aedes aegypti

- Agam

Anopheles gambiae

- Cqui

Culex quinquefasciatus

- Acep

Atta cephalotes

- Cflo

Camponotus floridanus

- Lhum

Linepithema humile

- Hsal

Harpegnathos saltator

- Pbar

Pogonomyrmex barbatus

- Nvit

Nasonia vitripennis

- Amel

Apis mellifera

- Phum

Pediculus humanus

- Bmor

Bombyx mori

- Apis

Acyrthosiphon pisum

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Behura SK. Molecular marker systems in insects: current trends and future avenues. Mol Ecol. 2006;15:3087–3113. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2006.03014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behura SK, Haugen M, Flannery E, Sarro J, Tessier CR, Severson DW, Duman-Scheel M. Comparative genomic analysis of Drosophila melanogaster and vector mosquito developmental genes. PLoS One. 2011;6:e21504. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behura SK, Severson DW. Coadaptation of isoacceptor tRNA genes and codon usage bias for translation efficiency in Aedes aegypti and Anopheles gambiae. Insect Mol Biol. 2011;20:177–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2010.01055.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behura SK, Stanke M, Desjardins CA, Werren JH, Severson DW. Comparative analysis of nuclear tRNA genes of Nasonia vitripennis and other arthropods and relationships to codon usage bias. Insect Mol Biol. 2010;19:49–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2583.2009.00933.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchan JR, Aucott LS, Stansfield I. tRNA properties help shape codon pair preferences in open reading frames. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:1015–1027. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Hoon MJ, Imoto S, Nolan J, Miyano S. Open source clustering software. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:1453–1454. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Rienzo A, Peterson AC, Garza JC, Valdes AM, Slatkin M, Freimer NB. Mutational processes of simple-sequence repeat loci in human populations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:3166–3170. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.8.3166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellegren H. Microsatellites: simple sequences with complex evolution. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5:435–445. doi: 10.1038/nrg1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golding GB. Simple sequence is abundant in eukaryotic proteins. Protein Sci. 1999;8:1358–1361. doi: 10.1110/ps.8.6.1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huntley M, Golding GB. Neurological proteins are not enriched for repetitive sequences. Genetics. 2004;166:1141–1154. doi: 10.1534/genetics.166.3.1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huntley M, Golding GB. Evolution of simple sequence in proteins. J Mol Evol. 2005;51:131–140. doi: 10.1007/s002390010073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huntley M, Golding GB. Selection and slippage creating serine homopolymers. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23:2017–2025. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huntley MA, Clark AG. Evolutionary analysis of amino acid repeats across the genomes of 12 Drosophila species. Mol Biol Evol. 2007;24:2598–2609. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlin S, Burge C. Trinucleotide repeats and long homopeptides in genes and proteins associated with nervous system disease and development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:1560–1565. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.4.1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashi Y, King DG. Simple sequence repeats as advantageous mutators in evolution. Trends Genet. 2006;22:253–259. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2006.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katti MV, Ranjekar PK, Gupta VS. Differential distribution of simple sequence repeats in eukaryotic genome sequences. Mol Biol Evol. 2001;18:1161–1167. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a003903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kofler R, Schlötterer C, Lelley T. SciRoKo: a new tool for whole genome microsatellite search and investigation. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:1683–1685. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruglyak S, Durrett RT, Schug MD, Aquadro CF. Equilibrium distributions of microsatellite repeat length resulting from a balance between slippage events and point mutations. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:10774–10778. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai Y, Sun F. The relationship between microsatellite slippage mutation rate and the number of repeat units. Mol Biol Evol. 2003;20:2123–2131. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msg228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levinson G, Gutman GA. Slipped-strand mispairing: A major mechanism for DNA sequence evolution. Mol Bio Evol. 1987;4:203–221. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcotte EM, Pellegrini M, Yeates TO, Eisenberg D. A census of protein repeats. J Mol Biol. 1999;293:151–160. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzgar D, Liu L, Hansen C, Dybvig K, Wills C. Domain-level differences in microsatellite distribution and content result from different relative rates of insertion and deletion mutations. Genome Res. 2002;12:408–413. doi: 10.1101/gr.198602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta T, Kimura M. A model of mutation appropriate to estimate the number of electrophoretically detectable alleles in a finite population. Genet Res. 1973;22:201–204. doi: 10.1017/s0016672300012994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richard GF, Pâques F. Mini- and microsatellite expansions: the recombination connection. EMBO Rep. 2000;1:122–126. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvd031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinsztein DC, Amos B, Cooper G. Microsatellite and trinucleotide-repeat evolution: evidence for mutational bias and different rates of evolution in different lineages. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1999;354:1095–1099. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1999.0465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlötterer C. Genome evolution: are microsatellites really simple sequences? Curr Biol. 1998;8:R132–4. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70989-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlotterer C, Tautz D. Slippage synthesis of simple sequence DNA. Nuc Acid Res. 1992;20:211–215. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.2.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma PC, Grover A, Kahl G. Mining microsatellites in eukaryotic genomes. Trends Biotechnol. 2007;25:490–498. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2007.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sutherland GR, Richards RI. Simple tandem DNA repeats and human genetic disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:3636–3641. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.9.3636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA4: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Bio Evol. 2007;24:1596–1599. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tautz D. Hypervariability of simple sequences as a general source for polymorphic DNA markers. Nucl Acids Res. 1989;17:6463–6471. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.16.6463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tautz D, Trick M, Dover G. Cryptic simplicity in DNA is a major source of genetic variation. Nature. 1986;322:652–656. doi: 10.1038/322652a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasemägi A, Nilsson J, Primmer CR. Expressed sequence tag-linked microsatellites as a source of gene-associated polymorphisms for detecting signatures of divergent selection in atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22:1067–1076. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber JL, Wong C. Mutation of human short tandem repeats. Hum Mol Genet. 1993;2:1123–1128. doi: 10.1093/hmg/2.8.1123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wernersson R, Pedersen AG. RevTrans: Multiple alignment of coding DNA from aligned amino acid sequences. Nuc Acid Res. 2003;31:3537–3539. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wierdl M, Dominska M, Petes TD. Microsatellite instability in yeast: dependence on the length of the microsatellite. Genetics. 1997;146:769–779. doi: 10.1093/genetics/146.3.769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu CH, Drummond AJ. Joint inference of microsatellite mutation models, population history and genealogies using transdimensional Markov Chain Monte Carlo. Genetics. 2011;188:151–164. doi: 10.1534/genetics.110.125260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zane L, Bargelloni L, Patarnello T. Strategies for microsatellite isolation: a review. Mol Ecol. 2002;11:1–16. doi: 10.1046/j.0962-1083.2001.01418.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.