Abstract

Objectives

To describe the adaptive capacity of the Adjusted Clinical Groups (ACG) system to the cost of care in primary healthcare centres in Catalonia (Spain).

Design

Retrospective study (multicentres) conducted using computerised medical records.

Setting

13 primary care teams in 2008 were included.

Participants

All patients registered in the study centres who required care between 1 January and 31 December 2008 were finally studied. Patients not registered in the study centres during the study period were excluded.

Outcome measures

Demographic (age and sex), dependent (cost of care) and case-mix variables were studied. The cost model for each patient was established by differentiating the fixed and variable costs. To evaluate the adaptive capacity of the ACG system, Pearson's coefficient of variation and the percentage of outliers were calculated. To evaluate the explanatory power of the ACG system, the authors used the coefficient of determination (R2).

Results

The number of patients studied was 227 235 (frequency: 5.9 visits per person per year), with a mean of 4.5 (3.2) episodes and 8.1 (8.2) visits per patient per year. The mean total cost was €654.2. The explanatory power of the ACG system was 36.9% for costs (56.5% without outliers). 10 ACG categories accounted for 60.1% of all cases and 19 for 80.9%. 5 categories represented 71% of poor performance (N=78 887, 34.7%), particularly category 0300-Acute Minor, Age 6+ (N=26 909, 11.8%), which had a coefficient of variation =139% and 6.6% of outliers.

Conclusions

The ACG system is an appropriate manner of classifying patients in routine clinical practice in primary healthcare centres in Catalonia, although improvements to the adaptive capacity through disaggregation of some categories according to age groups and, especially, the number of acute episodes in paediatric patients would be necessary to reduce intra-group variation.

Article summary

Article focus

In health management, separating financing, purchasing and the provision of services requires more precise instruments and measurement of healthcare activity.

The ACG Case-Mix System is a system of risk adjustment that classifies persons according to the diseases they present over a given period.

Key messages

The ACG system is an appropriate manner of classifying patients in routine clinical practice in primary healthcare centres in Catalonia.

Although improvements to the adaptive capacity through disaggregation of some categories according to age groups and, especially, the number of acute episodes in paediatric patients would be necessary to reduce intra-group variation.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The greatest limitations of the study are related to the quality of the records and information systems.

Without standardisation of methodologies in terms of patient characteristics and the number and measurement of variables, the results and their generalisability should be interpreted with caution.

Introduction

In health management, separating financing, purchasing and the provision of services requires more precise instruments and measurement of healthcare activity.1 2 Various countries are developing methods of per capita funding as a mechanism for allocating healthcare resources in a given region.3 The Adjusted Clinical Groups (ACG) Case-Mix System is a system of risk adjustment that classifies persons according to the diseases they present over a given period. The main objective is to measure the degree of disease in patient populations according to different levels of morbidity.4 5

Classification systems for ambulatory patients, especially primary healthcare (PHC) patients, have not been widely used even in the USA, where they mainly originated. In addition, there is some uncertainty about the adaptive capacity of these instruments in health fields other than that for which they were designed. These classification systems relate the burden of disease, consumption of resources and the real costs of care.6–11 Therefore, studies aimed at improving knowledge of the relationships between these factors can provide valuable evidence.

In general, ACG are accepted as useful in our setting and their use is increasing in various areas. However, some ACG categories seem to have excess variability and therefore we decided to study the performance of each ACG category in PHC centres in Catalonia.6 12 13

The aim of this study was to identify the retrospective adaptive capacity and poorly performing categories of the ACG system according to the cost of care in various PHC centres in Catalonia (Spain) in daily clinical practice.

Methods

Design and study population

We conducted a retrospective, multicentre study based on computerised medical records of PHC patients. All records were dissociated to ensure the confidentiality of the data. The study population consisted of all patients (N=310 235) assigned to 13 PHC centres in Catalonia belonging to four service providers. The patient population was predominantly urban, lower-middle class, with industrial occupations. All centres included provide universal free-at-the-point-of care healthcare with private provision of services in concert with the Catalan Health Service. All patients registered in the study centres who required care between 1 January and 31 December 2008 were finally studied. Patients not registered in the study centres during the study period were excluded.

Data retrieval and processing

Dependent variables were defined as the mean number of episodes and the direct costs of PHC. The independent variables analysed were age, sex, care provider and clinical service (family medicine (age ≥15 years) and paediatrics (age 0–14 years)). An episode or reason for consultation was considered as a care process equivalent to a diagnosis. The health problems diagnosed were coded using the International Classification for Primary Care (ICPC-2).14 A conversion (mapping) from ICPC-2 codes to ICD-9-CM was made by a working group (one documentalist, two clinicians and two technical consultants). Relationships between the ICPC-2 and ICD-9-CM were divided into three groups: (1) no relationship (ICPC-2 code with no equivalent in ICD-9-CM), (2) one-way relationship (one ICPC-2 code with a single equivalent in ICD-9-CM, the optimal situation) and (3) multiple relationships (one ICPC-2 code with several possible equivalents in ICD-9-CM).

The following measures were used to calculate overall morbidity: (1) the Charlson comorbidity index15 as an approximation of severity and (2) the individual case-mix index obtained using the ACG. The operating algorithm of the ACG Grouper V.8.2 (http://www.acg.jhsph.edu)16 consists of a series of consecutive steps that result in 106 ACG, which are mutually exclusive groups for each patient treated.

To construct an ACG, the age, sex and the reasons for consultation or diagnosis according to ICD-9-CM are required. The first stage groups the diagnoses of the ICD-9-CM in 32 Ambulatory Diagnostic Groups (ADG) (a patient may have one or more ADG), the second step groups the ADG into 12 Collapsed Ambulatory Diagnostic Groups, the third step transforms these into 25 Major Ambulatory Categories and finally these are transformed into an ACG category. At the end of the process, each patient is assigned to a single group with similar resource consumption. The application provides resource utilisation bands (RUB), with each patient being grouped into one of the five mutually exclusive categories according to their morbidity (1: healthy users, 2: low morbidity, 3: moderate morbidity, 4: high morbidity and 5: very high morbidity).4 5

To measure the performance or adaptive capacity of each ACG category (intra-group variability of the total cost of care), we used: (1) the Pearson's coefficient of variation (CV), in which a coefficient >100% was considered poor performance and (2) the percentage of outliers obtained through data refining of variables. The cut-off point (T) for outliers was established using the formula: T = Q3 + 1.5 (Q3 – Q1), where Q3 and Q1 are the third and first quartile of the distribution, respectively.

Use of resources and cost model

The design of the system of costs took into account the information requirements and degree of development of available information systems. The unit of care product used as the basis for the final calculation was the cost per patient treated during the study period. For each patient, we differentiated fixed costs and variable costs. The main fixed costs were staff (salaries and wages), purchases (drugs, medical supplies, etc), outsourced services (building repair and maintenance, professional services, etc) and a set of costs relating to structural services and centre management according to the General Accounting Plan for Health Care Centers. Fixed costs were allocated per visit (mean/unit: fixed costs/total number of visits). Variable costs per patient were calculated according to diagnostic petitions (laboratory, radiology, diagnostic or therapeutic, referrals to specialists and drug prescriptions). The tariffs used to calculate costs came from analytical cost-accounting studies (see table 1). Finally, the cost per patient was calculated as: Cp = (mean cost per visit × number of visits (fixed costs)) + (variable costs).

Table 1.

Mean unit costs in 2008

| Health resources | Unit cost (€) |

| Health visit | 23.62 |

| Laboratory tests | 22.70 |

| Conventional radiology | 18.84 |

| Diagnostic tests/therapy | 37.85 |

| Referral to reference specialist | 106.29 |

| Drug prescriptions | RRPvat |

Analytical accounting conducted for this study.

RRPvat, recommended retail price including Value Added Tax.

Data confidentiality

According to Spanish law, being a retrospective design and because it is not investigated the effectiveness of any medicine, the study does not need specific approval from an institutional review board or the patient's consent but instead required the dissociation of the data. The confidentiality of records according to the Organic Law on Data Protection (15/1999, 13 December) was respected by dissociating the data.

Data quality and statistical analysis

In a preliminary analysis, we carefully reviewed the medical records to observe their frequency and distribution and to search for possible errors in recording or coding. We performed a descriptive univariate analysis including mean values, SD, proportions and percentiles. The normal distribution of variables was confirmed using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. In the bivariate analysis, we used the χ2 test, the Student t test, ANOVA, Pearson's linear correlation and the Mann–Whitney–Wilcoxon non-parametric test. To evaluate the explanatory power of the ACG system, we used the coefficient of determination (R2) obtained from the ratio intra-group variability/total variability (ANOVA). The analysis was made using the SPSS for Windows V.18 statistical package. Statistical significance was established as p<0.05.

Results

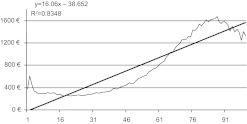

A total of 227 235 patients were registered in the study centres in 2008 (86.5% in family medicine and 13.5% in paediatrics). Table 2 details the general characteristics of the patient population, the comorbidity and the total costs. Patients had a mean of 4.5 (3.2) episodes and 8.1 (8.2) visits per year. The percentage of men (51.1% vs 43.3%, p<0.001) and visits (9.7 vs 7.8, p<0.001) were higher in paediatric patients. The mean age of women was higher than that of men, 39.2 vs 37.8 (p<0.001). The total cost was €148.7 million (93.3% for family medicine). Drugs were prescribed to 80.1% of patients. Fixed costs accounted for 29.1% of total costs and variable costs for 70.9% (including 47.5% on drug prescriptions). Therefore, the mean total cost per patient/year was €654.2 (851.7), €702.5 in family medicine and €344.6 in paediatric (p<0.001). A total of 6.2% of patients were considered outliers, and after data refining, the mean unitary cost per year was €556.7. The association between the mean/unit cost according to age is shown in figure 1.

Table 2.

General characteristics of study: comorbidity and cost model

| Characteristics | Total |

| Patients | N=227 235 |

| General | |

| Number of physicians | 224 |

| Number of episodes | 1 020 606 |

| Number of visits | 1 834 326 |

| Mean age, years | 44.1 (23.7) |

| 25 percentile | 27.0 |

| 50 percentile | 43.0 |

| 75 percentile | 67.0 |

| Sex (female) | 55.6% |

| General comorbidity | |

| Mean ADG | 3.7 (2.2) |

| 25 percentile | 2.0 |

| 50 percentile | 3.0 |

| 75 percentile | 5.0 |

| Mean episodes | 4.5 (3.2) |

| Mean Charlson index | 0.2 (0.6) |

| RUB | 2.4 (0.8) |

| 1 | 16.9% |

| 2 | 31.0% |

| 3 | 47.9% |

| 4 | 3.8 |

| 5 | 0.5 |

| Outliers (N=14 066) | 6.2% |

| Mean/unit | % | |

| Cost model (in euros)/year | ||

| Fixed costs | 190.7 (193.3) | 29.1 |

| Laboratory | 51.9 (73.8) | 7.9 |

| Conventional radiology | 21.4 (34.1) | 3.3 |

| Complementary tests | 6.2 (19.6) | 1.0 |

| Referrals to specialists | 73.1 (117.3) | 11.2 |

| Drug prescriptions | 310.8 (681.2) | 47.5 |

| Total cost of PHC | 654.2 (851.7) | 100.0 |

| Cost of family medicine | 92.9% | |

| Cost of paediatric medicine (0–14 years) | 7.1% | |

Values expressed as mean (SD) or percentage.

RUB, resource utilisation bands; ADG, Ambulatory Diagnostic Groups; PHC, primary healthcare.

Figure 1.

Correlation of the cost of care according to age. R2: coefficient of determination.

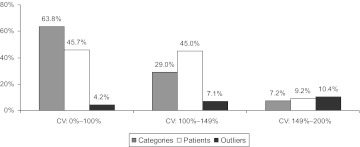

The performance (patient distribution) and adaptive capacity (intra-group variation in categories) of the ACG classification are shown in table 3. All patients were grouped in a category. However, no patients were grouped in 37 of the 106 categories, meaning that all patients were grouped in the remaining 69 categories. Furthermore, 61% of all patients were grouped in 10 categories and 80.9% in 19 (N=183 721, table 3). This distribution showed no significant differences according to the service provider. In 10 ACG categories, a poor performance (poor adaptive capacity) was observed (CV >100%, N=110 917, 48.8% of patients, table 3 and figure 2). The two categories with the highest CV were 1600-Preventive/Administrative (N=8527, 3.8%, outliers: 12.5%) and 1300-Psychosocial, w/o Psychosocial Unstable (N=3653, 1.6%, outliers: 10.7%).

Table 3.

Distribution of ACG categories with the most patients: variability of categories

| ACG | ACG description | N | % | Cost* | CV | Outliers† |

| 4100 | 2-3 Other ADG Combinations, Age 35+ | 28 864 | 12.7 | 776.3 | 107 | 6.5 |

| 0300 | Acute Minor, Age 6+ | 26 909 | 11.8 | 169.6 | 139 | 6.6 |

| 4910 | 6-9 Other ADG Combinations, Age 35+, 0-1 Major ADGs | 14 876 | 6.5 | 1624.4 | 67 | 4.5 |

| 2100 | Acute Minor/Likely to Recur, Age 6+, w/o Allergy | 11 867 | 5.2 | 304.7 | 91 | 5.3 |

| 4410 | 4-5 Other ADG Combinations, Age 45+, no Major ADGs | 10 551 | 4.6 | 1025.4 | 74 | 5.3 |

| 4420 | 4-5 Other ADG Combinations, Age 45+, 1 Major ADGs | 10 137 | 4.5 | 1336.2 | 79 | 4.6 |

| 0500 | Likely to Recur, w/o Allergies | 9872 | 4.3 | 187.2 | 140 | 6.6 |

| 1800 | Acute Minor/Acute Major | 9077 | 4.0 | 353.2 | 104 | 5.9 |

| 1600 | Preventive/Administrative | 8527 | 3.8 | 229.5 | 215 | 12.5 |

| 0400 | Acute Major | 8160 | 3.6 | 237.3 | 160 | 8.1 |

| 0900 | Chronic Medical: Stable | 6319 | 2.8 | 506.7 | 114 | 6.2 |

| 3900 | 2-3 Other ADG Combinations, Males Age 18 to 34 | 5877 | 2.6 | 341.7 | 117 | 6.0 |

| 3200 | Acute Minor/Acute Major/Likely to Recur, Age 12+, w/o Allergy | 5785 | 2.5 | 525.0 | 89 | 6.3 |

| 2300 | Acute Minor/Chronic Medical: Stable | 5756 | 2.5 | 612.6 | 95 | 6.3 |

| 3600 | Acute Minor/Acute Major/Likely to Recur/Chronic Medical: Stable | 5575 | 2.5 | 1022.1 | 72 | 5.0 |

| 4310 | 4-5 Other ADG Combinations, Age 18 to 44, no Major ADGs | 4168 | 1.8 | 554.8 | 86 | 6.4 |

| 4920 | 6-9 Other ADG Combinations, Age 35+, 2 Major ADGs | 4089 | 1.8 | 2102.5 | 67 | 3.5 |

| 2800 | Acute Major/Likely to Recur | 3659 | 1.6 | 351.0 | 102 | 6.9 |

| 1300 | Psychosocial, w/o Psychosocial Unstable | 3653 | 1.6 | 340.4 | 175 | 10.7 |

Nineteen ACG categories contain 80.9% of patients (N=183 721). No patient was grouped in 37 ACG categories; ACG, Adjusted Clinical Groups (Code)*: Gross cost (mean/unit in euros), CV: Pearson's coefficient of variation† :outliers: percentage of patients, cut-off: T = Q3 + 1.5 (Q3 − Q1), where Q3 and Q1 are the third and first quartiles of the distribution, respectively. Total sample: N=227 235, CV =130.0%, outliers: 6.2%.

Figure 2.

Percentage distribution of coefficients of variation according to the number of categories, patients and outliers. CV: Pearson's coefficient of variation; contrast statistic: χ2, p<0.001 for all categories.

We carried out a more-detailed analysis according to poor performance and the number of patients in each category. Table 4 shows the distribution of five ACG categories (making up 71% of poorly performing categories, N=78 887). Compared with the total of 69 categories (N=227 235), these five categories had a lower explanatory power (coefficient of determination, R2) in episodes (44.3% vs 77.4%) and total costs (18.8% vs 36.9%), p<0.001. For refined data, the results were 46.4% vs 78.4% for episodes and 36.5% vs 56.5% for total costs, p<0.001. Category 0300-Acute Minor, Age 6+ (N=26 909; 11.8%) had a CV =139% and 6.6% of outliers and showed significant differences before and after data refining. Categories 0400-Acute Major (N=8160) and 1800-Acute Minor/Acute Major (N=9077) performed similarly. Category 4100-2-3 Other ADG Combinations, Age 35+, had the highest number of patients (N=28 864, 12.7%), with a high mean number of episodes (3.9 of total cases compared with 4.5 in outliers, p<0.001), resulting in increased costs in these patients. The R2 of the five poorly performing categories was 34.7%.

Table 4.

Distribution of five poorly performing ACG categories according to age, episodes and cost

| ACG categories (coding and description) | Total |

No outliers |

Outliers |

|||

| Variables | N | Mean | N | Mean | N | Mean |

| 4100: 2-3 Other ADG Combinations, Age 35+ | 28 864 | 26 992 | 1872 | |||

| Age | 60.5 (14.8) | 59.7 (14.6) | 70.9 (12.8) | |||

| Episodes | 3.9 (1.3) | 3.9 (1.2) | 4.5 (1.5) | |||

| Total cost | 776.3 (828.2) | 620.3 (448.7) | 3026.1 (1504.4) | |||

| 0300: Acute Minor, Age 6+ | 26 909 | 25 142 | 1767 | |||

| Age | 33.1 (16.5) | 31.9 (15.4) | 50.5 (22.1) | |||

| Episodes | 1.7 (1.1) | 1.7 (0.9) | 2.5 (1.4) | |||

| Total cost | 169.5 (236.5) | 125.2 (91.7) | 800.0 (554.3) | |||

| 1800: Acute Minor/Acute Major | 9077 | 8538 | 539 | |||

| Age | 32.1 (19.8) | 30.8 (18.5) | 51.6 (27.1) | |||

| Episodes | 3.6 (1.5) | 3.6 (1.4) | 4.8 (2.3) | |||

| Total cost | 353.2 (366.2) | 288.7 (166.5) | 1374.2 (843.8) | |||

| 0400: Acute Major | 8160 | 7503 | 657 | |||

| Age | 38.5 (18.2) | 36.6 (16.7) | 59.9 (20.6) | |||

| Episodes | 1.6 (0.8) | 1.5 (0.7) | 2.1 (1.1) | |||

| Total cost | 237.3 (379.5) | 158.3 (108.7) | 1139.1 (877.8) | |||

| 3900: 2-3 Other ADG Combinations, Males Age 18 to 34 | 5877 | 5523 | 354 | |||

| Age | 28.1 (4.5) | 28.0 (4.5) | 28.7 (4.2) | |||

| Episodes | 3.3 (1.0) | 3.3 (1.1) | 3.8 (1.2) | |||

| Total cost | 341.6 (399.1) | 273.7 (154.1) | 1401.2 (1040.1) | |||

Contrast statistic: χ2 test or Mann–Whitney–Wilcoxon test; p<0.001 in all cases.

ADG, Ambulatory Diagnostic Groups.

Discussion

This study determined the retrospective adaptive capacity of the ACG classification system according to the cost of PHC in Catalonia (Spain) in daily clinical practice, identifying 10 categories that performed poorly in the Catalan health system. In Catalonia, the use of capitation-based funding is still in its infancy compared with other European healthcare systems. The focus is on incorporating risk adjustment indicators in order to provide unbiased estimates of the expected costs of an individual patient in each health plan.2–17

There is abundant published evidence on the use and overall performance of the ACG classification, but evidence on categories that perform poorly is very limited.4–7 9 12 18–24 It is expected that persons with similar morbidity and demographic characteristics will have a similar use of resources. In this respect, the available empirical evidence shows that it is technically possible to find an adjustment formula to predict at least a portion of the variation in health expenditure per person and also that the highest predictive values are achieved by systems that incorporate diagnostic information.6 21 25 This has been proven in our study since the number of episodes showed a greater explanatory power with respect to ACG categories than the total costs. Furthermore, data refining may lessen the weight of random factors in predicting expenditure, although it is known that no system of classification of patients into RUB explains all the variation in the use of resources.6 7 10 26

In general, the Grouper requires a limited number of variables for each patient: age, sex and diagnosis (not necessarily correlated in time). This simplicity of use is compatible with the needs of PHC, which must work with large daily volumes of information, limited time for each patient, professional cooperation (doctors, nurses, social workers, etc) and repeated visits from the same patient. However, a greater degree of computerisation of PHC and the establishment of mechanisms for consensus between health professionals would be required to increase data quality and the consistency of records, especially in the identification of diagnoses.11 23

The general results of the study (demographic variables (age and sex), case mix (morbidity) and resource use levels (RUB)) fall within the parameters expected in PHC in Spain. Furthermore, the distribution of patients within ACG categories is similar to the results obtained in other studies (60% of patients are grouped in 10 ACG categories) and stable over time.4 6 8 9 12 18–23 25–28

This may be because the grouping works by binary combinations of ADG, regardless of the number of recurrences and the type of disorder.4 5 For example, a patient with one or more episodes of upper respiratory tract infection over time, with or without concomitant pharyngitis, may remain grouped in the same ACG category, resulting in widely differing use of resources and degree of variation in costs. This point has been suggested by some authors as a limitation of the ACG system, although recent years have seen an expansion of categories from 51 to 103 to avoid such problems.23

Poor performance or adaptive capacity was observed in 10 ACG categories (N=110 917, 48.8% of patients). The two categories with the highest CV were Preventive/Administrative and Psychosocial, w/o Psychosocial Unstable. These results are difficult to compare for several reasons: (1) these categories include many different circumstances and conditions (administrative processes, preventive actions and health promotion, unstable conditions with an unpredictable risk of recurrence, etc), (2) these conditions tend to be associated with poor-quality medical records (prescriptions not linked to a diagnosis, etc) and (3) the presence of different organisational models between centres (patient circuits, etc) as a result of health policies, causing a high degree of variability that affects the use of resources and their costs.

We found that five categories accounted for 71% of poor performance. In general, acute disease (0300-Acute Minor, Age 6+, 0400-Acute Major and 1800-Acute Minor/Acute Major), representing a large number of paediatric patients, had a poor adaptive capacity. The ACG classification in Catalonia might be improved by expanding some of these categories according to age groups and, especially, by quantifying the number of episodes occurring during the study period. However, in the categories 4100-2-3 Other ADG Combinations, Age 35+ and 3900-2-3 Other ADG Combinations, Males Age 18–34, the performance with respect to classification into RUB could be improved by separating different ranges of episodes or ADG.

Therefore, a possible scenario for the debate on the funding model for PHC teams could be developed using a combination of factors: (1) the weighting of structural costs related to accessibility; (2) the variable costs according to the case mix (ACG) and patient complexity, adapting the classification to the country and (3) quality targets derived from the policy sought by the purchaser and expected by the customer. In this aspect, the adaptive capacity of the ACG system to the Catalan setting could be bettered by improving the definition of some categories. This would facilitate policy making using benchmarking with respect to the complexity (case mix) and efficiency of PHC centres with the population served, enabling capitation payments (risk adjustment).4 26

The greatest limitations of the study are related to the quality of the records and information systems. Without standardisation of methodologies in terms of patient characteristics and the number and measurement of variables, the results and their generalisability should be interpreted with caution.24 In addition, possible differences between health professionals in the selection of diagnoses may contaminate the comparison of costs between groups. However, strength of the study is that the large sample size could minimise these drawbacks. The ACG system was designed to measure the health status and medical resources consumed in a set of patients and, therefore, population-based studies of risk-adjusted capitation payments and the clinical management of PHC centres may be of considerable interest in Catalonia.23 29

Conclusions

The ACG system is an appropriate manner of classifying patients in routine clinical practice in PHC centres in Catalonia, although improvements to the adaptive capacity through disaggregation of some categories according to age groups and, especially, the number of acute episodes in paediatric patients would be necessary to reduce intra-group variation.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

To cite: Sicras-Mainar A, Velasco-Velasco S, Navarro-Artieda R, et al. Adaptive capacity of the Adjusted Clinical Groups Case-Mix System to the cost of primary healthcare in Catalonia (Spain): a observational study. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000941. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-000941

Contributors: AS-M, SV-V, RN-A, CV-F and AP-T planned the study. AS-M, RN-A and SV-V supervised the campaign registration, data entry and follow-up. AS-M was responsible for the statistical analysis with help from SV-V. AS-M wrote the first draft of the paper and has the primary responsibility for the final content. All authors contributed to and approved the final manuscript. AS-M is the head of the Catalan study.

Funding: This work was supported by Fondo de Investigaciones Sanitarias de la Seguridad Social (Instituto Carlos III, Majahonda, Madrid, Spain), grant number PI 08/1567.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: The study project was approved by the Ethics and Clinical Research Committee of the Jordi Gol Clinical Research Institute (IDIAP Jordi Gol).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Rice N, Smith P. Capitation and risk adjustment in health care financing: an international progress report. Milbank Q 2001;79:81–113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Forrest CB, Lemke KW, Bodycombe DP, et al. Medication, diagnostic, and cost information as predictors of high-risk patients in need of care management. Am J Manag Care 2009;15:41–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rico A, Saltman RB, Boerma WG. Organizational restructuring in European health care systems: the role of primary care. Social Policy Admin 2003;37:592–608 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weiner JP, Starfield BH, Steinwachs DM, et al. Development and application of a population-oriented measure of ambulatory care case-mix. Med Care 1991;29:452–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Starfield B, Lemke KW, Bernhardt T, et al. Comorbidity: implications for the importance of primary care in ‘case’ management. Ann Fam Med 2003;1:8–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sicras-Mainar A, Serrat-Tarres J. Measurement of relative cost weights as an effect of the retrospective application of adjusted clinical groups in primary care. Gac Sanit 2006;20:132–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petersen LA, Pietz K, Woodard LD, et al. Comparison of the predictive validity of diagnosis-based risk adjusters for clinical outcomes. Med Care 2005;43:61–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hughes JS, Averill RF, Eisenhandler J, et al. Clinical Risk Groups (CRGs): a classification system for risk adjusted capitation-based payment and health care management. Med Care 2004;42:81–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meenan RT, Goodman MJ, Fishman PA, et al. Using risk-adjustment models to identify high-cost risks. Med Care 2003;41:1301–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Buglioli M, Bonilla M, Ortún Rubio V. Sistemas de ajuste por riesgo. Rev Med Uruguay 2000;16:123–32 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fusté J, Bolíbar B, Castillo A, et al. Hacia la definición de un conjunto mínimo básico de datos de atención primaria. Aten Primaria 2002;30:229–35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aguado A, Guino E, Mukherjee B, et al. Variability in prescription drug expenditures explained by adjusted clinical groups (ACG) case-mix: a cross-sectional study of patient electronic records in primary care. BMC Health Serv Res 2008;8:53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sicras-Mainar A, Serrat-Tarrés J, Navarro-Artieda R, et al. Adjusted Clinical Groups use as a measure of the referrals efficiency from primary care to specialized in Spain. Eur J Public Health 2007;17:657–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lamberts H, Wood M, Hofmans-Okkes IM, eds. The International Classification of Primary Care in the European Community. With a Multi-language Layer. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis 1987;40:373–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The Johns Hopkins ACG® Case-mix System version 8.2. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vargas I. La utilización del mecanismo de asignación per cápita: la experiencia de Cataluña. Cuadernos de Gestión 2002;8:167–78 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fishman PA, Goodman MJ, Hornbrook MC, et al. Risk adjustment using automated ambulatory pharmacy data: the RxRisk model. Med Care 2003;41:84–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosen AK, Loveland SA, Rakovski CC, et al. Do different case-mix measures affect assessments of provider efficiency? Lessons from the Department of Veterans Affairs. J Ambul Care Manage 2003;26:229–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shen Y, Ellis RP. How profitable is risk selection? A comparison of four risk adjustment models. Health Econ 2002;11:165–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Carlsson L, Strender LE, Fridh G, et al. Types of morbidity and categories of patients in a Swedish county. Applying the Johns Hopkins Adjusted Clinical Groups System to encounter data in primary health care. Scand J Prim Health Care 2004;22:174–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reid RJ, MacWilliam L, Verhulst L, et al. Performance of ACG case-mix system in two Canadian provinces. Med Care 2001;39:86–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chang HY, Weiner J. An in-depth assessment of a diagnosis-based risk adjustment model based on national health insurance claims: the application of the Johns Hopkins Adjusted Clinical Group case-mix system in Taiwan. BMC Med 2010;8:7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sackett D, Rosenberg W, Gray J, et al. Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn't. BMJ 1996;312:71–2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Orueta JF, Urraca J, Berraondo I, et al. Adjusted Clinical Groups (ACGs) explain the utilization of primary care in Spain based on information registered in the medical records: a cross-sectional study. Health Policy 2006;76:38–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greenwald LM. Medicare risk-adjusted capitation payments: from research to implementation. Health Care Financ Rev 2000;21:1–5 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reid RJ, Roos NP, MacWilliam L, et al. Assessing population health care need using a claims-based ACG morbidity measure: a validation analysis in the Province of Manitoba. Health Serv Res 2002;37:1345–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kuo R, Lai MS. Comparison of Rx-defined morbidity groups and diagnosis based risk adjusters for predicting healthcare costs in Taiwan. BMC Health Serv Res 2010;10:126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gosden T, Forland F, Kristiansen IS, et al. Capitation, salary, fee-for-service and mixed systems of payment: effects on the behaviour of primary care physicians. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000;(3):CD002215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.