Abstract

Introduction

Some general practitioners (GPs) treat acute low back pain (LBP) with acupuncture, despite lacking evidence of its effectiveness for this condition. The aim of this study was to evaluate whether a single treatment session with acupuncture can reduce time to recovery when applied in addition to standard LBP treatment according to the Norwegian national guidelines. Analyses of prognostic factors for recovery and cost-effectiveness will also be carried out.

Methods and analysis

In this randomised, controlled multicentre study in general practice in Southern Norway, 270 patients will be allocated into one of two treatment groups, using a web-based application based on block randomisation. Outcome assessor will be blinded for group allocation of the patients. The control group will receive standard treatment, while the intervention group will receive standard treatment plus acupuncture treatment. There will be different GPs treating the two groups, and both groups will just have one consultation. Adults who consult their GP because of acute LBP will be included. Patients with nerve root affection, ‘red flags’, pregnancy, previous sick leave more than 14 days and disability pension will be excluded. The primary outcome of the study is the median time to recovery (in days). The secondary outcomes are rated global improvement, back-specific functional status, sick leave, medication, GP visits and side effects. A pilot study will be conducted.

Ethics and dissemination

Participation is based on informed written consent. The authors will apply for an ethical approval from the Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics when the study protocol is published. Results from this study, positive or negative, will be disseminated in scientific medical journals.

Trial Registration Number

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT01439412.

Article summary

Article focus

Does acupuncture treatment contribute to faster pain recovery in acute LBP compared with standard treatment in general practice provided in accordance with the Norwegian national guidelines?

Does acupuncture treatment for acute LBP improve function and reduce drug use and sick leave?

Is acupuncture treatment for acute LBP a cost-effective treatment in general practice?

Key messages

This project will increase the knowledge about the effects of acupuncture treatment for acute LBP.

The primary outcome is the median time in days for recovery from pain.

A faster pain relief will aid the patients to earlier return to normal, everyday activities, including return to their work.

Strengths and limitations of this study

The methodology of the trial is stronger than previous studies.

There are still methodological challenges in acupuncture trials; in this trial, neither the patient or the GP will be blinded, and the consultation time will be longer in the intervention group.

Introduction

Low back pain (LBP) is a very common disorder with consequences for the individual patient as well as for the society. Up to 80% of the population experiences back pain at least once in their lifetime, about 50% during the previous year. Point prevalence is 15%, and the condition relapses frequently, 40% within 6 months.1 Back pain is the medical condition that ranks highest in terms of Norwegian socioeconomic expenses.2 Most people with acute LBP experience improvements in pain and disability within a month,3 but the median time to recovery recorded in studies on back pain varies widely, from 7 to 58 days.4 5

Acute LBP is treated primarily in the primary healthcare by general practitioners (GPs), physiotherapists, manual therapists and chiropractors. Recommended treatment according to clinical guidelines contains information about the condition, advice to stay active and, if possible, avoid bed rest, early and gradual mobilisation after the acute phase, pain treatment with paracetamol and/or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) with time-contingent doses.2 6

GPs educated and trained in acupuncture also use acupuncture for the treatment of both acute and chronic LBP cases.7 There is evidence that acupuncture is effective in chronic LBP, and such treatment is therefore recommended in the ‘National guidelines for LBP’ in Norway.2 8–10 Reviews and meta-analyses conclude that the documentation of acupuncture treatment for acute LBP is limited by few and poorly conducted studies, however.10 11 In a systematic review conducted by Yuan et al,12 the authors concluded that for non-specific LBP, treatment regimens of acupuncture differ by the types of reference sources, in terms of treatment frequency, the points chosen, number of points needled per session, duration and sessions, and co-interventions.

In 1997, He13 presented a Chinese study with 100 patients afflicted with LBP (5 days to 6 months duration) randomised to either manual acupuncture with moxibustion plus Chinese herbal medicine or Chinese herbal medicine alone. A later Cochrane review concludes that this trial was of low methodological quality and showed limited evidence to back the fact that the combined treatment was more effective for a global measure of pain and function in the long-term follow-up.10

Araki et al have published an abstract of a trial where 40 patients with acute LBP (<3 days) were randomised into two groups where the intervention group got acupuncture treatment in the acupuncture point SI3 bilaterally and then performed back exercises. The control group, however, received sham acupuncture treatment with mimicked needle insertion, after which they were asked to perform back exercises. Araki et al14 found no difference between the effects of acupuncture and that of the sham acupuncture.14

One of the studies referred to in the Cochrane review is a Norwegian study conducted by Kittang et al.15 They found that acupuncture was as effective as medical treatment with Naproxen per os in relation to pain and stiffness, but that the ‘Naproxen-group’ had more side effects and greater recurrences in the observation period. While Kittang et al conclude that acupuncture is effective, this result is based on other studies showing the efficacy of NSAIDs for acute LBP.16

Kennedy et al published a pilot study in 2008, which demonstrated the feasibility of a randomised controlled trial regarding the penetrating needle acupuncture when compared with non-penetrating sham acupuncture for the treatment of acute LBP in primary care. However, the study lacked sufficient power to draw any conclusion on treatment effects.17

Sham acupuncture involves inserting penetrating or non-penetrating needles in points that are not classical acupuncture points and/or are not located in the same segment. Several studies conclude, however, that sham acupuncture is not a valid placebo control, and this is explained by neurophysiologic effects of the sham treatment.18 19 Trials with sham acupuncture need to be very comprehensive in order to demonstrate differences between the effects of real acupuncture and the sham treatment.20

In 2006, Vas et al21 published a study protocol of a four-branch randomised controlled trial, which intended to obtain further evidence on the effectiveness of acupuncture on acute LBP and isolate the specific and non-specific effects of the treatment. The results have not yet been published. Shin et al22 are planning to perform a randomised controlled trial with two arms comparing a motion-style acupuncture with an NSAID injection.

However, we have not yet found evidence favouring acupuncture as a treatment for acute LBP. Our clinical experience is that an acupuncture treatment of the distal and local acupuncture points combined with small mobilising movements means faster recovery of the pain. This treatment is according to some textbooks on acupuncture.23 24 No researchers, according to the referred protocols, plan to examine this kind of acupuncture. All the points that we plan to use are mentioned among the common points used for LBP in the systematic review by Yuan et al,12 and mobilising movements are often used as a co-intervention for acute LBP.

Strong stimulation of the distal acupuncture points is thought to act through activation of the extra-segmental pain inhibition, ‘Diffuse noxious inhibitory Controls’ and the release of endorphins and possibly, other endogenous compounds in the central nervous system. Local acupuncture therapy immediately following the mobilisation movements may provide additional benefits through segmental pain inhibition along with the inhibition of myofascial trigger points.25

Clear prognostic factors for the efficacy of acupuncture for chronic LBP have, however, not been documented. In a large German study, the authors found that lower age, lower baseline spinal function and more than 10 years of education indicated a better response to acupuncture.26 Some researchers still find that optimistic treatment expectations improve the effects of acupuncture,27 28 while others find the best treatment effects in patients who are neutral to acupuncture as a treatment method.29 There are no similar studies for acute LBP.

A systematic review found evidence supporting the cost-effectiveness of the guideline-endorsed treatments of acupuncture for subacute or chronic LBP.30 Apart from the few trials of acupuncture treatment for acute LBP, there are no studies examining the cost-effectiveness of acupuncture for acute LBP.

In the present study, we aim at exploring whether a single treatment session with acupuncture can reduce the time to recovery when applied in addition to the standard LBP treatment in general practice according to Norwegian national guidelines. We will not use sham acupuncture as a control treatment. Furthermore, we will not include a pure placebo group or a ‘waiting list group’ because this will mean not giving treatment to patients with severe pain, which we consider unethical.

Secondary aims are pain intensity, disability, sick leave and drug use, and in addition we will evaluate the prognostic factors for recovery, and if possible, identify any factors that characterise those who have beneficial effects of the acupuncture treatment.

Finally, we also aim at carrying out a cost-effectiveness analysis.

Our hypotheses are

Acupuncture treatment contributes to faster pain recovery in acute LBP compared with standard treatment in general practice provided in accordance with the Norwegian national guidelines.

Acupuncture treatment for acute LBP improves function and reduces drug use and sick leave, compared with the standard treatment in general practice provided in accordance with national guidelines.

Acupuncture treatment for acute LBP is a cost-effective treatment in general practice.

Methods and analysis

This is a randomised, controlled multicentre study, which will involve 15 GP group practices located in different areas in southern Norway, both cities and rural municipalities. The 15 GPs administering the acupuncture have received their training through the education programme of the Norwegian Society of Medical Acupuncture and are members of the Network Group of Medical Acupuncture, under the Norwegian College of General Practice. They are specialists in general practice, and many of them are experienced participants in randomised clinical trials, given a parallel ongoing trial examining the effects of acupuncture on infantile colic.31 32 Fifteen GPs in the same practices, but without training in acupuncture, will be recruited to treat the control group.

A medical secretary at every doctor's office will carry out the telephonic interview in which the patients will be informed about the study, the inclusion and exclusion criteria will be checked, the randomisation of the patients will be performed and the distributing and collecting questionnaires for the treatment day. A two-day workshop before the start of the main study will be arranged for all the participating doctors and medical secretaries. The workshop will contribute to the standardisation of information, reporting and patient management in general. A website with information about the study will be created.

We plan to recruit patients with acute LBP and randomly allocate them into two parallell study groups (A and C) of equal sizes. Patients in both groups will receive standard treatment for LBP in accordance with the Norwegian national guidelines.2 One group will receive only the standard treatment, while the other group also will receive additional acupuncture treatment as described below. To control for potential attention bias, we will measure the time spent on each patient in the intervention and control groups. Outcome assessor will be blinded for group allocation of the patients.

Inclusion criteria

Adults (20–55 years) who contact their GP's office because of acute non-specific LBP (0–14 days).

Exclusion criteria

Nerve root affection and/or radiating pain below the knee.

LBP with suspected ‘red flags’, that is, infections, tumours and metastatic disease, rheumatic disease, fractures and significant deformities of the spine.

LBP that starts in pregnancy.

Physician-reported sick leave of 14 days or more during the month before the commencement of the back pain, for any reason.

Disability pension.

Control group C

Standard treatment in general practice is provided in accordance with the Norwegian national guidelines, that is, general advice about activity, prescription of pain relievers (paracetamol) and sick leave, if needed.

Acupuncture group A

This group will receive standard treatment as the control group and in addition acupuncture treatment.

Acupuncture: The patient sits in a chair and the doctor stimulates the acupuncture points ‘the Lumbar Pain Points’ (Yaotongxue/Yaotongdian) on the right hand, with acupuncture needles of type Seirin B-8a 0.30 × 30 mm. These are two points located between the second and third and the fourth and fifth metacarpal bones, immediately distal to the bases of the metacarpals. Insertion depth is 10–15 mm. The doctor stimulates the needles in a rotating up and down movement to impart a powerful needle sensation (called ‘de Qi’), and this is repeated in short sequences to maintain the needle sensation for a total of 1 min. The needles shall stay in the hand during the rest of the treatment. The patient is then asked to rise and to perform slow rotating pelvic movements for 2 min, before lying down on a bench to be treated in the local points Huatuojiaji (‘Jiaji’) with acupuncture needles of the type SEIRIN J-8 with sleeve 0.30 × 50 mm. These points are located 1.5 cm lateral to the depressions below the spinous processes, and we will acupuncture them bilaterally in the segments of the L2–L4 (six needles) at a depth of 3–4 cm. They are stimulated manually until the patient experiences the needle sensation. Then, the patient lies quietly on the bench for another 5 min before all the needles are removed.

The whole acupuncture session lasts for a total of 8 min. Thus, part of the advice and prescription part is done while the patient is receiving acupuncture treatment, in order to let the consultation time for the two groups be as equal as possible. The consultation time will be measured and registered by the GPs. The duration of the acupuncture treatment in this trial is shorter than in earlier trials, and we will only have one treatment session.12 This is to reduce potential attention bias.

Choice of treatment

The described treatment with the specific distal and local acupuncture points has been chosen after a three-step process. We started with the treatment we used ourselves in clinical practice, compared it with the literature and standardised it for this trial. Then, we asked several experienced acupuncture doctors how they treated acute LBP and what they thought about our suggestion of standardisation.

Based on this feedback, we asked an expert group of physicians and physiotherapists experienced in administering acupuncture about which acupuncture points they preferred in the treatment of acute LBP. The end result was considered the treatment according to best practice for this study.

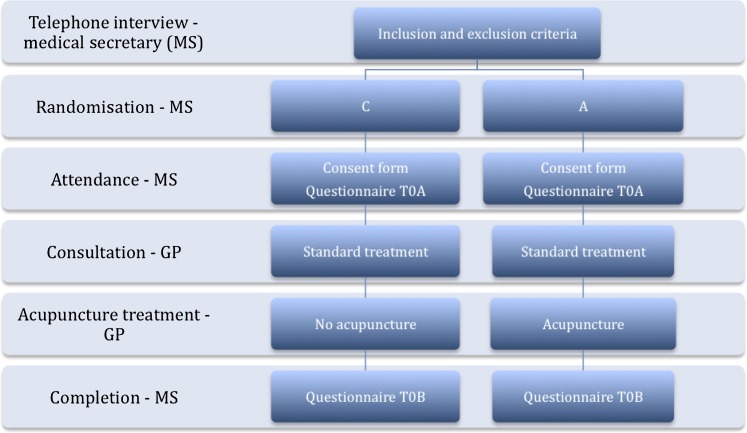

Patient flow

When a patient with acute LBP contacts the GP's office, the medical secretary provides information about the trial and asks whether the patient would want to participate in the study.

The patient will be informed that he/she will meet a GP and get the usual treatment for LBP and may or may not get acupuncture in addition to the usual treatment. During the observation period of 12 months, patients are asked for not to receive any additional acupuncture treatments.

If the patient consents, the medical secretary asks the patient questions regarding inclusion and exclusion criteria. The inclusion and exclusion criteria are checked both in the telephone interview by the secretary and in the consultation by the GP. All contacts are counted, and it is recorded at what level and for what reason exclusions are done. If the patient is eligible, the medical secretary randomises the patient to one of the two groups through the web-based application at the Unit for Applied Clinical Research in Trondheim (http://www.ntnu.no/dmf/akf). This is used to register the patient in the appropriate doctor's timetable, but the patient does not know which group or which doctor he/she is going to meet.

At the GP's office, the patient is required to fill in the consent form and the first questionnaire (T0A). This is delivered to the medical secretary prior to the consultation.

Patients who are randomised to the control group will receive one standard treatment provided by a GP without acupuncture training. The consultation will include history, examination, information, prescription and advices, according to national guidelines for LBP. If the doctor discovers exclusion criteria, the patient will be excluded from the trial.

Patients who are randomised to the acupuncture group will receive one single acupuncture treatment in addition to the standard treatment as described for the control group. The consultation will be provided by a GP who is trained in acupuncture. If the patient's condition requires further consultations in the follow-up time, these will be recorded. These consultations, however, will not include additional acupuncture treatment.

When the patient has finished the consultation, they will fill in a post-treatment questionnaire (T0B) and submit it to the secretary in an enclosed envelope. The patient then will receive a back pain diary, which he/she will be required to fill in at home at the given times. The diary also contains information about how the patient can choose to give the answers in an electronic questionnaire (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Patient flow during inclusion, randomisation and treatment.

Measurements

For evaluation of the effects of treatment, we will use standardised instruments that have been validated, both internationally and nationally.33 34 The outcome measures will be filled in at baseline and after 1, 2, 4, 12 weeks and 12 months, and the following outcome measurements will be included:

The primary outcome is the median time in days to the recovery of pain, measured on the first day the patient scores 0 or 1 point on the Numerical Rating Scale. Clinically relevant differences between the groups are considered to be minimum 3 days.

Secondary outcome measures will be:

Pain intensity is assessed by the numerical rating scale before and immediately after treatment and at the other follow-up times. The patient indicates his perceived pain intensity on an 11-point scale from 0 to 10 with endpoints indicating ‘no pain’ and ‘worst imaginable pain’. Based on other studies, clinical relevant improvement is estimated to 1.5 points in a previous Norwegian study on patients with acute LBP.35

Back-specific functional status by the Roland Morris Disability Questionnaire. This measures patients' perceptions of function.36 The patient answers yes or no concerning24 allegations about the activities and conditions, depending on whether they feel that the statement describes them on this day.

Sick leaves, the number of days away from work due to back pain.

Global measure of improvement (Likert improvement assessment scale). This assesses the patients' perceptions of change, stated in whole numbers from 1= much better to 5= much worse.

Use of medication (paracetamol, eventually others), counting of daily consumption.

Number of new visits at the GP's office.

Side effects of treatment (acupuncture and medications).

Health-related quality-of-life by the EuroQoL (EQ-5D). This enumerates five questions that map the following areas: walking, personal care, daily activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression, as well as a 100 mm VAS (Visual Analogue Scale).37

In addition, the patients will be asked to fill in a back pain diary. This refers to a small printed matter where the patient completes a daily questionnaire about the condition, as an aid to remember the results between each registration in the electronic questionnaire. It contains question about the pain level, function, use of medications, side effects and other comments every day for 2 weeks, 4 and 12 weeks and 12 months after treatment.

The following questions will be included at the baseline for describing the baseline characteristics of the included sample and for the evaluation of potential prognostic factors for recovery:

Socio-demographic variables: This refers to age, gender, marital status, education, smoking status, use of alcohol, height, weight and serious life events during the 12 last months.

In addition, we will ask the patients about their preferences for the two treatment options for LBP and if they believe that acupuncture will contribute to faster recovery than the usual treatment.

Örebro screening form for musculoskeletal pain: These are 25 questions that map all the main ‘yellow flags’. This questionnaire about the pain and how it influences job-related activities shows prognostic factors for acute LBP.38 39

Subjective health complaints: Here, the patient indicates in what degree he/she has had 29 different health complaints the last 30 days and how long the complaints have lasted.40

Patients will fill in the questionnaire at baseline (before the first treatment) and then immediately after the first treatment at the GPs office. Patients will fill in the back pain diary at home every day for 2 weeks, after 4 and 12 weeks and after 12 months. They may choose to fill in the results directly in the electronic questionnaire. If the results are not registered electronically, the patients may have to send the hard copy version of the diary to the project leader after 12 weeks. The last questionnaire has to be sent after 12 months, which is the maximum follow-up time.

Patients will receive a SMS reminder about the registration. If the patient does not respond to the electronic questionnaire or the back pain diary, he/she will be reminded by SMS or telephone twice. Those who withdraw will be asked for the reason for doing so.

Sample size

We have calculated that a total of 270 patients will be needed for the study. Based on previous studies and clinical experience, we estimate that the 3 days' difference in median time to recovery between the acupuncture group and control group is clinically significant, with a median time to recovery of 7 days in the intervention group.4 41 42 The probability is 80% that the study will detect a treatment difference at a two sided 5% significance level, if the true HR is 1.429. This is based on the assumption that the accrual period will be 0 days, the follow-up period will be 365 days and the median survival is 7 days.43 In addition, we calculate with up to 10% dropout in the study.

Pilot study

Prior to the main study, we plan to conduct a pilot study to test the study design, the assessment and reporting tools with a total of eight patients, four in each group.

Randomisation

Randomisation will be performed by a web-based randomisation system developed and administered by the Unit of Applied Clinical Research, Institute of Cancer Research and Molecular Medicine, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway, and it will use block randomisation with various sizes of the blocks.

Each patient is randomised after the inclusion and exclusion criteria are considered. It is the GP's medical secretary who checks the randomisation online, and the patient is then given an appointment with either the ‘control-GP’ or the ‘acupuncture-GP’. The patient is not told which group he/she is randomised to or the name of the GP before the consent form and the first questionnaire are filled in.

Analyses

Data will be analysed by an outcome assessor who is blinded to group status. The groups will be analysed only as group 1 and group 2, and the results presented in tables and figures will be worked out before the codes are broken. The primary analyses will be by intention to treat, and we will restrict the number of analyses in order to reduce the possibility of type I errors. For primary outcomes, a p value of <0.05 will be considered statistically significant. For the secondary outcomes, a p value of <0.01 will be considered significant.

Primary outcome analyses

We will assess the difference in survival curves (days to recovery) for the two groups using the log-rank statistic. The median days to recovery will be used to express the time to recovery for the two groups. Cox regression will be used to assess the effect of treatment group on HRs after allowing for the days of pain duration as baseline covariate.

Secondary outcome analyses

Differences between the groups will be presented as mean with 95% CI or in categories with OR for categorical data. A mixed model with group as a fixed factor will be used for the other outcome measures. Post hoc analyses will be conducted if there is a significant difference between treatment groups. We will also test for potential confounding factors in these models. Analyses of prognostic factors will be carried out by a multivariate regression models.

Ethics and dissemination

When the patient contacts the GPs office, he/she will be informed about the objectives of the study and asked if he/she is willing to participate. The patients will be told that their participation is voluntary and that they will be granted full anonymity. Informed written consent will be required from the included patients.

All patients will receive the treatment they normally would receive from their GP, but half of them will undergo acupuncture treatment in addition to this. Given the randomisation, some patients will not meet their usual GP. Instead, another GP will consult the patient, though in the same office.

The risk of side effects of the acupuncture treatment has been found to be low.44–46 We will examine any side effects of the treatment during the trial.

The trial is registered in the ClinicalTrials.gov-register, NCT01439412.

We plan to apply to the Regional Ethics Committee of South-Eastern Norway when the protocol is published.

Publication policy

The results of the trial will be published in appropriate journals regardless of outcome. The trial will be implemented and reported in accordance with the recommendations of CONSORT and STRICTA.

Discussion

This paper presents the design and rationale for a randomised, controlled multicentre study examining the effects of acupuncture on the recovery of patients with acute LBP. The project will increase the knowledge about the effects of acupuncture treatment for acute LBP, a common disorder seen by GPs entailing high costs for the patient and society. For the individual, a faster pain relief will aid an earlier return to normal everyday activities. For the society, the effect may be that LBP patients will return earlier to their work. The primary outcome is the median time in days for recovery from pain. The secondary outcomes are rated global improvement, back-specific functional status, sick leaves, medication, GP visits and side effects. A pilot study will be conducted. In the present study, we will also analyse possible prognostic factors for recovery and cost-effectiveness of acupuncture treatment for LBP.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Magne Thoresen, Professor of Biostatistics, University of Oslo, for assistance with the statistical power calculation.

Footnotes

To cite: Skonnord T, Skjeie H, Brekke M, et al. Acupuncture for acute non-specific low back pain: a protocol for a randomised, controlled multicentre intervention study in general practice—the Acuback Study. BMJ Open 2012;2:e001164. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001164

Contributors: TS and HS initiated the project. TS, HS, MB, MG, IL and AF all contributed to conceptualisation and design of the study, and all revised this manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: TS has received research grants from the Norwegian College of General Practitioners to plan this trial. The study funder will not have any impact on the trial and the publication of the results.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: We want to have the protocol peer-reviewed before applying the Regional Ethics Committee. Then, we can apply with the finally edited protocol. When the protocol is accepted for publication, we will apply the Regional Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Carey TS, Garrett JM, Jackman A, et al. Recurrence and care seeking after acute back pain: results of a long-term follow-up study. North Carolina Back Pain Project. Med Care 1999;37:157–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laerum E, Brox JI, Storheim K, et al. National Clinical Guidelines. Low Back Pain with and Without Nerve Root Affection. Oslo: Formi, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pengel LH, Herbert RD, Maher CG, et al. Acute low back pain: systematic review of its prognosis. BMJ 2003;327:323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coste J, Delecoeuillerie G, Cohen de Lara A, et al. Clinical course and prognostic factors in acute low back pain: an inception cohort study in primary care practice. BMJ 1994;308:577–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henschke N, Maher CG, Refshauge KM, et al. Prognosis in patients with recent onset low back pain in Australian primary care: inception cohort study. BMJ 2008;337:a171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hunskaar [Textbook of General Practice]. Oslo: Gyldendal Norsk Forlag AS, 2003:338–41 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hopton AK, Curnoe S, Kanaan M, et al. Acupuncture in practice: mapping the providers, the patients and the settings in a national cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manheimer E, White A, Berman B, et al. Meta-analysis: acupuncture for low back pain. Ann Intern Med 2005;142:651–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yuan J, Purepong N, Kerr DP, et al. Effectiveness of acupuncture for low back pain: a systematic review. Spine (Phila Pa) 2008;33:E887–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Furlan AD, van Tulder MW, Cherkin DC, et al. Acupuncture and dry-needling for low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;2:CD001351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Furlan AD, Yazdi F, Tsertsvadze A, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of efficacy, cost-effectiveness, and safety of selected complementary and alternative medicine for neck and low-back pain. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2012;2012:953139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yuan J, Kerr D, Park J, et al. Treatment regimens of acupuncture for low back pain–a systematic review. Complement Ther Med 2008;16:295–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He RY. Clinical observation on treatment of lumbago due to Cold-Dampness by Warm-acupuncture plus Chinese medicine. Chin Acupuncture Moxibustion 1997;17:279–80 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Araki S, Kawamura O, Mataka T, et al. Randomized controlled trial comparing effect manual acupuncture sham acupuncture acute low back pain. J Jpn Soc Acupuncture Moxibustion 2001;51:382 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kittang G, Melvaer T, Baerheim A. Acupuncture contra antiphlogistics in acute lumbago (In Norwegian). Tidsskr Nor Laegeforen 2001;121:1207–10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Tulder MW, Scholten RJ, Koes BW, et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000;(2):CD000396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kennedy S, Baxter GD, Kerr DP, et al. Acupuncture for acute non-specific low back pain: a pilot randomised non-penetrating sham controlled trial. Complement Ther Med 2008;16:139–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lund I, Naslund J, Lundeberg T. Minimal acupuncture is not a valid placebo control in randomised controlled trials of acupuncture: a physiologist's perspective. Chin Med 2009;4:1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lundeberg T, Lund I, Naslund J, et al. The Emperors sham—wrong assumption that sham needling is sham. Acupunct Med 2008;26:239–42 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Linde K, Niemann K, Schneider A, et al. How large are the nonspecific effects of acupuncture? A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Med 2010;8:75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vas J, Perea-Milla E, Mendez C, et al. Efficacy and safety of acupuncture for the treatment of non-specific acute low back pain: a randomised controlled multicentre trial protocol [ISRCTN65814467]. BMC Complement Altern Med 2006;6:14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shin JS, Ha IH, Lee TG, et al. Motion style acupuncture treatment (MSAT) for acute low back pain with severe disability: a multicenter, randomized, controlled trial protocol. BMC Complement Altern Med 2011;11:127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deadman P, Al-Khafaji M, Baker K. A manual of acupuncture. 3 edn. J Chinese Medicine 2008:574–80 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Heyerdahl O, Lystad N. [Textbook of Acupuncture]. Oslo: Universitetsforlaget, 2007:291–303 [Google Scholar]

- 25.White A, Cummings M, Filshie J. An Introduction to Western Medical Acupuncture. London: Churchill Livingstone Elsevier, 2008:7–76 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Witt CM, Jena S, Selim D, et al. Pragmatic randomized trial evaluating the clinical and economic effectiveness of acupuncture for chronic low back pain. Am J Epidemiol 2006;164:487–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kalauokalani D, Cherkin DC, Sherman KJ, et al. Lessons from a trial of acupuncture and massage for low back pain: patient expectations and treatment effects. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2001;26:1418–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Linde K, Witt CM, Streng A, et al. The impact of patient expectations on outcomes in four randomized controlled trials of acupuncture in patients with chronic pain. Pain 2007;128:264–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thomas KJ, MacPherson H, Thorpe L, et al. Randomised controlled trial of a short course of traditional acupuncture compared with usual care for persistent non-specific low back pain. BMJ 2006;333:623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lin CW, Haas M, Maher CG, et al. Cost-effectiveness of guideline-endorsed treatments for low back pain: a systematic review. Eur Spine J 2011;20:1024–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Skjeie H, Skonnord T, Fetveit A, et al. A pilot study of ST36 acupuncture for infantile colic. Acupunct Med 2011;29:103–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.ClinicalTrials Effects of Acupuncture in the Treatment of Infant Colic (NCT00907621). 2009. http://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00907621?term=NCT00907621&rank=1 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mannion AF, Elfering A, Staerkle R, et al. Outcome assessment in low back pain: how low can you go? Eur Spine J 2005;14:1014–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mannion AF, Porchet F, Kleinstuck FS, et al. The quality of spine surgery from the patient's perspective. Part 1: the Core Outcome Measures Index in clinical practice. Eur Spine J 2009;18(Suppl 3):367–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grotle M, Brox JI, Vollestad NK. Concurrent comparison of responsiveness in pain and functional status measurements used for patients with low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2004;29:E492–501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roland M, Morris R. A study of the natural history of back pain. Part I: development of a reliable and sensitive measure of disability in low-back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1983;8:141–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Solberg TK, Olsen JA, Ingebrigtsen T, et al. Health-related quality of life assessment by the EuroQol-5D can provide cost-utility data in the field of low-back surgery. Eur Spine J 2005;14:1000–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Linton SJ, Hallden K. Can we screen for problematic back pain? A screening questionnaire for predicting outcome in acute and subacute back pain. Clin J Pain 1998;14:209–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grotle M, Vollestad NK, Brox JI. Screening for yellow flags in first-time acute low back pain: reliability and validity of a Norwegian version of the Acute Low Back Pain Screening Questionnaire. Clin J Pain 2006;22:458–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Grovle L, Haugen AJ, Ihlebaek CM, et al. Comorbid subjective health complaints in patients with sciatica: a prospective study including comparison with the general population. J Psychosom Res 2011;70:548–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Curtis P, Carey TS, Evans P, et al. Training primary care physicians to give limited manual therapy for low back pain: patient outcomes. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2000;25:2954–60; discussion 60–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hancock MJ, Maher CG, Latimer J, et al. Assessment of diclofenac or spinal manipulative therapy, or both, in addition to recommended first-line treatment for acute low back pain: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2007;370:1638–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schoenfeld D. Find Statistical Considerations for a Study Where the Outcome is a Time to Failure. 2001. http://hedwig.mgh.harvard.edu/sample_size/time_to_event/para_time.html [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vincent C. The safety of acupuncture. BMJ 2001;323:467–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.White A. A cumulative review of the range and incidence of significant adverse events associated with acupuncture. Acupunct Med 2004;22:122–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Witt CM, Pach D, Brinkhaus B, et al. Safety of acupuncture: results of a prospective observational study with 229,230 patients and introduction of a medical information and consent form. Forsch Komplementmed 2009;16:91–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.