Abstract

Objectives

The cancer multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting (MDM) is regarded as the best platform to reduce unwarranted variation in cancer care through evidence-compliant management. However, MDMs are often overburdened with many different agendas and hence struggle to achieve their full potential. The authors developed an interactive clinical decision support system called MATE (Multidisciplinary meeting Assistant and Treatment sElector) to facilitate explicit evidence-based decision making in the breast MDMs.

Design

Audit study and a questionnaire survey.

Setting

Breast multidisciplinary unit in a large secondary care teaching hospital.

Participants

All members of the breast MDT at the Royal Free Hospital, London, were consulted during the process of MATE development and implementation. The emphasis was on acknowledging the clinical needs and practical constraints of the MDT and fitting the system around the team's workflow rather than the other way around. Delegates, who attended MATE workshop at the England Cancer Networks' Development Programme conference in March 2010, participated in the questionnaire survey.

Outcome measures

The measures included evidence-compliant care, measured by adherence to clinical practice guidelines, and promoting research, measured by the patient identification rate for ongoing clinical trials.

Results

MATE identified 61% more patients who were potentially eligible for recruitment into clinical trials than the MDT, and MATE recommendations demonstrated better concordance with clinical practice guideline than MDT recommendations (97% of MATE vs 93.2% of MDT; N=984). MATE is in routine use in breast MDMs at the Royal Free Hospital, London, and wider evaluations are being considered.

Conclusions

Sophisticated decision support systems can enhance the conduct of MDMs in a way that is acceptable to and valued by the clinical team. Further rigorous evaluations are required to examine cost-effectiveness and measure the impact on patient outcomes. The decision support technology used in MATE is generic and if found useful can be applied across medicine.

Article summary

Article focus

How to improve the conduct of a cancer MDT and standardise decision making in accordance with best evidence.

Development and implementation of a novel clinical decision support (CDS) platform for breast cancer MDT.

This study evaluates (1) the concordance between the CDS suggestions and MDT recommendations and (2) the identification rate of potentially eligible patients for recruiting into the ongoing research trials, by the MDT and the CDS. A separate questionnaire survey was conducted at the national workshop at the Cancer Networks' Development Programme to get an estimate of acceptability of such MDT decision support systems by the cancer networks.

Key messages

An advanced CDS platform could significantly improve the conduct of cancer MDMs.

Further robust evaluations are necessary.

Strengths and limitations of this study

We share our experience of developing an advanced decision support system and implementing it in a complex clinical environment of cancer MDT, which was subsequently adopted as a breast MDMs management tool.

The results reported here, however encouraging, are at this point indicative of the potential benefits but not yet conclusive. They should be treated with caution until further rigorous evaluations confirm the effectiveness and generalisability of the CDS system.

Problem statement

Unwarranted practice variation across different medical domains has unfortunately become a pervasive finding in health service research, and breast cancer care is no exception.1 A recently published study reported significant differences in breast cancer survival across hospitals in the same geographical region in England.2 The reasons for practice variation are multifactorial, and standardisation of care has been attempted by the introduction of Regional Cancer Networks in England and the adoption of the multidisciplinary team (MDT) model to promote maximal adoption of evidence-based practice. The MDT model is increasingly being adopted in other non-cancer medical domains, such as stroke, cardiovascular diseases and diabetes.

Many benefits of MDTs have been claimed, but few have been backed by strong evidence.3 4 However, despite a significant lack of prospective evidence, MDTs are well accepted in clinical practice; they are regarded as a major advance in management of patients with cancer and their use appears to be increasing.5 As many healthcare systems have already committed to and invested in the MDT model, further reductions in unwarranted variation are likely to be best achieved by improving their conduct and standardising their decision-making processes.6 Data collected by the UK national cancer peer review programme from over 1000 teams across six cancer types in England indicate that there is significant room for improvement in the conduct of MDT meetings (MDMs) and show considerable variability in the performance of MDTs.7 A recent national survey of more than 2000 members of cancer MDTs demonstrated agreement on the range of criteria necessary for effective MDT working.3 A review of the literature by the authors identified many pragmatic challenges and shortcomings in the current conduct of cancer MDMs summarised in box 1.8

Box 1. Pragmatic challenges for cancer MDT meetings.

Ensuring and documenting adherence with standards (eg, evidence-based guidelines).

Identifying patients who are eligible for recruitment into clinical trials.

Ensuring the consistent collection of crucial data, such as disease staging and outcomes.

Establishing robust mechanisms for prospective assessment of MDT performance.

Ensuring MDT recommendations are followed in practice.

Achieving the right balance of educational and care delivery objectives of this forum.

Establishing reliable interfaces with primary care to ensure continuity of care.

Context

The Royal Free Hospital NHS Trust (RFH) serves a population of 2.6 million within the North London Cancer Network catchment area. The number of new patients (both benign and cancer) seen as outpatients by the breast unit in 2009–2010 was 2944. The Breast Cancer MDT at RFH was established in 2005, in line with the recommendations of the NHS Cancer Plan. The MDT uses a set of North London Cancer Network-approved clinical guidelines and a standardised minimum data set.

MDMs are held every week in a conventional conference format (figure 1). The core members of a breast MDT include breast surgeons, radiologists, pathologists, medical and clinical oncologists, plastic surgeons and breast clinical nurse specialists. A typical breast MDM discusses an average of 30–40 patients at various stages in their care pathways every week to decide further courses of action in their management.

Figure 1.

MATE (Multidisciplinary meeting Assistant and Treatment sElector) in use at Royal Free breast multidisciplinary team meeting.

Prior to the introduction of our computer-based service into the MDMs, an entirely paper-based record system was used to provide case summaries and to document the MDT's discussion and decisions. These records contained free (unstructured) text rather than coded and structured data. The trade-offs between structured (computer interpretable) and unstructured electronic health records (EHRs) are well known.9 Recording MDT discussions in an unstructured form, such as free-text clinical notes, scanned documents, pdfs, hinders the process of accurate measurement of MDT performance as computer-based data analysis and auditing tools cannot be used on unstructured data.

There are many commercially available information and communication systems, which can assist in the preparation, presentation and documentation of cases at the MDMs, such as EHR systems. However, the objectives of our MDT service improvement exercise was to go beyond improvements in data management by providing active support for evidence-based decision making, improving recruitment into clinical trials and supporting prospective audit.10

Measures of improvement

Evidence compliant care: adherence with clinical practice guidelines

With the increasing recognition of shortcomings in healthcare systems, there is a significant cultural and professional shift towards using evidence-based guidance. Evidence-based standards of care, such as published practice guidelines and technology assessment reports developed by authoritative organisations, provide an objective standard against which to assess MDT decisions. There is growing evidence that use of evidence-based guidelines can improve patient outcomes,11–13 and MDMs provide the best opportunity to actively promote an appropriate and judicious use of the guidelines at the point of care.

Promoting research: identification of patients eligible for ongoing research trials

It is widely accepted that recruiting patients into clinical trials is an effective strategy for ensuring that cancer patients get the best care as well as providing important information about the efficacy of treatments. However, the literature continues to report low rates of accrual to cancer clinical trials,14 and many organisations at national and international levels are investigating strategies for improving accrual rates. Cancer MDMs offer a major opportunity for identifying patients who are eligible for participation in clinical trials.15

Methods

In order to assess the performance of the breast MDT on the above-mentioned measures, we developed a computerised decision support system, MATE (Multidisciplinary meeting Assistant and Treatment sElector), that captures patient data, identifies eligible patients for clinical trials and suggests evidence-based treatment recommendations. MATE also captures MDT decisions and hence can automatically compare them with guideline recommendations.

System development

We followed a systematic stepwise approach throughout the system development lifecycle. Requirements for MATE were identified through a systematic review of the literature8 and by working closely with members of the breast MDT at RFH. We adopted the common knowledge acquisition and design system (CommonKADS) methodology to develop a comprehensive process and knowledge model for breast cancer MDMs.16 A controlled vocabulary from the National Cancer Institute thesaurus17 was used to facilitate data standardisation. The evidence sources reviewed included clinical practice guidelines, systematic reviews and meta-analyses and reports of randomised controlled trials. Along with the guideline recommendations, the eligibility criteria of ongoing clinical trials in breast cancer that were open for recruitment at our institution were also coded into the system.

PROforma,18 an established decision modelling language for modelling clinical decisions and care pathways, was used to formalise decisions and supporting evidence in MATE. The PROforma language and application development software Tallis used in this project were originally developed at the Cancer Research UK. Tallis was used to implement a range of decision support and other servicesi as determined by the requirements development process outlined above and is used to update recommendations and other components of the PROforma knowledge base when new guidance is published. Tallis is being developed jointly by Oxford University and the Royal Free development team.

System description

MATE functionality can be categorised under two broad headings: (1) structured data capture, presentation and audit, and (2) advanced evidence-based decision support.

Data capture: MATE allows users to capture detailed structured clinical data, including, demographics, comorbidities, test results, clinical findings, imaging, pathology and treatment-related data. The data are entered into the system either before (preparation phase) or during the MDMs (presentation phase). In the preparation phase, the data are entered by a clinician, who is responsible for the preparation of the meeting. Data entry is flexible, quick and secure, and it was found to reduce preparation time. If some of the test results such as pathology reports are not available before the MDT meeting, they can easily be entered in MATE during the meeting by a clinician without delaying the proceedings. MATE also provides patient summaries automatically and prospective audit facilities.

Advanced evidence-based decision support module: It is the key component of MATE that sets it apart from cancer tracking systems, EHR systems and the first-generation decision support, such as rule-based alert and reminder systems. MATE actively evaluates diagnostic markers histopathological data and other patient-related factors, such as co-morbidities to generate patient-specific recommendations for clinical management. The Tallis decision support technology enables MATE to rank the recommended options: for example, if the fitness of the patient is in question due to comorbidity, MATE can recommend the next best option with supporting evidence. In principle, patient preferences can also be factored into the MATE decision process and we are actively exploring ways of doing this in line with widely discussed needs for greater patient empowerment.

All clinical recommendations made by MATE are presented to the user together with a summary of the rationale in the form of arguments and supporting evidence. The MATE knowledge base has been developed with reference to a comprehensive set of published national and international clinical practice guidelines, which enables MATE to give recommendations even in complex cases that are covered by these guidelines.

MATE also provides quantitative risk estimates based on published models as an adjunct to the clinical recommendations.

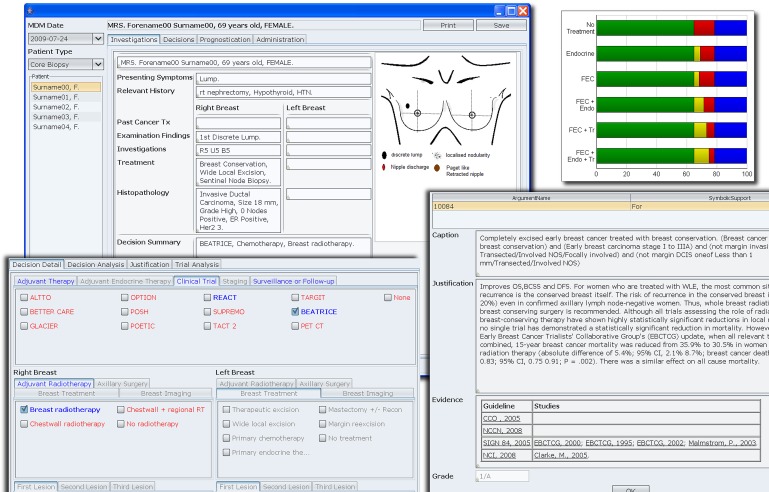

The user interface of MATE is illustrated in figure 2. The detailed description of the knowledge base, technology and architecture is published elsewhere.19

Figure 2.

Composite screenshot showing the user interface and some of the functionalities of MATE (Multidisciplinary meeting Assistant and Treatment sElector). Upper left: the summary screen for the patient; upper right: one of the many prognostication tools available; lower left: decision panel where system recommendations and eligible clinical trials are highlighted in blue; lower right: the evidential justification for each recommended option.

Evaluation of concordance between MATE and MDT recommendations

MATE was used in the background to prospectively record the proceedings of breast MDMs between April 2008 and July 2009 to gather 1295 cases discussed in the MDMs during this period (each time a patient was discussed in the MDT meeting was counted as a separate encounter). The patient data and the MDT decisions were entered in MATE during the meeting by the first author. MATE recommendations were not shown to the MDT to avoid any confounding effect. After the meeting, the correctness of patient data and MDT recommendations entered in MATE were cross-checked with the official paper MDT records by a research associate from the research team and, in case of any discrepancies, the patient data and MDT decisions entered in MATE record data were amended to be in line with the official MDT record. Approval for an audit study was obtained from the Research and Development department of the hospital before starting the study, and data-security measures such as encryption were put in place.

One of the key features of MATE comparedwith a traditional EHR is the clinical decision support (CDS) element. MATE is able to actively evaluate patient data and to offer guideline-based recommendations in real time, which are specific for each individual patient. We compared MATE recommendations with the MDT decisions. The discordant cases (where MATE recommendations differed from those of MDT decisions) were further investigated by a panel who reviewed the patient's clinical notes. MATE also automatically flags patients who meet eligibility criteria for ongoing clinical trials.

Structured feedback from members of cancer networks in the UK

The MATE development team was invited to conduct a workshop at the England Cancer Networks' Development Programme conference in March 2010. The conference was attended by key members from all cancer networks, who are instrumental in governing and improving MDT conduct in their respective cancer networks. MATE was demonstrated in a workshop, and a questionnaire survey was conducted at the end of the presentation and discussion session. The aim of the structured feedback was to gather the views of the members of cancer networks about the usefulness of CDS systems in general and MATE in particular, in the context of cancers MDMS.

Respondents were asked to select from a choice of five categories (strongly agree, agree, neutral, disagree, strongly disagree) for five structured questions regarding usefulness of the system. They were also asked open-ended questions to find any perceived barriers and their general comments. For simplicity, we have combined ‘strongly agree’ and ‘agree’ responses into an overall ‘agree’ rating and ‘neutral’, ‘disagree’ and ‘strongly disagree’ responses into a an overall ‘disagree’ rating. The ‘neutral’ category was included in ‘disagree’ to ensure a conservative interpretation.

Results

Evaluation phase results

The case mix of 1295 breast cases included cancers and benign pathologies. Table 1 shows the overall distribution of cases recorded on the MATE system during the study. Metastatic, recurrent and non-epithelial malignancies were excluded from the guideline concordance analysis as the guidelines and evidence-base for those subsets were not initially coded in MATE. In 239 cases of recurrent metastatic or non-epithelial malignancies, MATE therefore provided data capture services but no decision support. The remaining 1056 cases were analysed for concordance between management recommendations made by MATE and the actual MDT decisions; the level of concordance was encouragingly high (93.2%; N=984). When the 6.8% discordant cases were further analysed, it was found that in 3.2% cases, the MDT decisions that differed from MATE recommendations were corrected by the treating clinician in the results clinic.

Table 1.

Distribution of breast cases discussed at MDM according to type

| Pathology | Number |

| Benign breast disease | 413 |

| Operable breast cancer (in situ and invasive) | 511 |

| No final diagnosis reached (eg, C1/C3/C4 on cytology or B1/B3/B4 on core biopsy) at the time of MDT meeting | 132 |

| Metastatic and/or recurrent cancers | 198 |

| Other than breast epithelial malignancies | 41 |

| Total cases | 1295 |

MDT, multidisciplinary team; MDM, MDT meeting.

MATE also identified 61% more patients who were potentially eligible for recruitment into clinical trials than the MDT alone. Note that MATE only screens the patients as possibly eligible for the trials, based on the main eligibility criteria. All the information needed before recruiting the patient is often not available to the MDT. Certain tests specific for the trial (eg, 2D Echo for ejection fraction) are done after MDT discussion, and the results are not available at the MDM.

Structured feedback results

The MATE workshop at the Cancer Networks' Development Programme conference was attended by 54 people, of whom 48 completed the questionnaire. The roles of respondents were categorised as follows:

Clinicians (Doctors and Nurses) = 13

Patients/survivors = 5

Service improvement managers = 18

Informaticians = 7

Others = 5

There was a very high consensus on the usefulness of CDS in general, and MATE in particular, for cancer MDMs. Most respondents (95.8%) agreed that CDS has a useful role in cancer MDMs. The majority of respondents found the services provided by MATE useful for the breast MDM (93.47) and potentially for other types of cancer MDMs (92.6%). The CDS component and ability to automatically screen patients for ongoing clinical trials were seen as the two most valuable capabilities of MATE by the majority of respondents (84.5% and 81.2% of respondents, respectively). Other capabilities of MATE, identified as valuable were patient data capture (70% of respondents), clinical audit services (67%), peer review support (58%) and education/training (45%). The majority of respondents (73.8%) were favourable to recommending MATE if it were made available in their network.

The survey also identified important barriers to large-scale deployment of MATE. The main perceived obstacle to adoption was double data entry (50%) in situations where existing data capture systems are in place, and it was suggested that MATE should be able to interface with existing data capture systems. Other barriers identified were costs and resources, clinical buy-in, scalability and the need for appropriate knowledge maintenance mechanisms that can cope with the large volumes of clinical evidence.

Challenges and next steps

We wish to emphasise that the role of MATE or any similar IT system is purely supportive and the MDT meeting continues to be led by the clinical team. Advanced IT systems can only complement an effective and functional MDT20 and cannot compensate for inherent weaknesses in team composition, organisation or operation. The preliminary audit results and the qualitative assessment data reported in this study, however encouraging, are at this point indicative of the potential benefits but not yet conclusive until further rigorous evaluations confirm the effectiveness and generalisability of MATE or similar services.

Generalisability

It has been reported that CDS systems produce better results when the developing team is also responsible for the trial of the system. One review reported, for example, that the success rate for CDS systems dropped from 74% to 28% when the systems were tested by independent teams.21 The team involved in the development of MATE was also involved in testing and the deployment of the system so replication of our results on other sites is a key objective. It was for the same reason that the questionnaire survey from the user was not conducted at this stage, and this is planned during the wider implementation phase. Demonstrating that MATE can confer significant benefits for other cancer MDTs is also a high priority. MATE has attracted the attention of the UK Department of Health's National Cancer Action Team, and deployment of the system in other NHS trusts is being explored.

Effectiveness trials

Definitive evidence of the value of complex (multifaceted) interventions such as MATE requires a multicentre trial in which a cluster randomised design is likely to be the preferred methodology.22 The trial should look into all important impacts of the intervention, including quantitative measures of cost, patient outcomes and process measures as well as qualitative measures.

Patient empowerment

Patient involvement in decisions about their treatment is widely considered to be crucial to improving outcomes, and many cancer patients wish to play a more active role in their care. The current structure of the cancer MDT meeting makes patient participation very difficult to achieve.23 We are therefore exploring ways in which MATE could facilitate patient engagement, by extending access to certain of its functions by the patients. This could be achieved in a variety of settings, including consultations in results clinic and from the patient's home using the internet, allowing the patients to review their clinical history, the MDT recommendations and the reasons and justifying evidence for those recommendations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Cancer Research UK for funding the development and the trial of the system and all members of the breast multidisciplinary team at Royal Free for their consistent support.

Footnotes

To cite: Patkar V, Acosta D, Davidson T, et al. Using computerised decision support to improve compliance of cancer multidisciplinary meetings with evidence-based guidance. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000439. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000439

Contributors: All authors have made substantial contributions as follows: VP, JF and MK: conception and design; VP, DA, TD, AJ and MK: conducting the pilot study; VP and DA: developing the MATE knowledge base and software, and acquisition of data; VP and MK: analysis and interpretation of data; VP, DA, JF and MK: drafting the article. All authors: revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and have given final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: The development and subsequent trial of the MATE decision support system was funded by Cancer Research UK by an extramural programme grant to JF.

Competing interest: VP, DA, JF and MK have following specified non-financial interests that may be relevant to the submitted work. UCL (B) (a subsidiary of University College London) and ISIS innovation (a subsidiary of the University of Oxford) are actively seeking to commercialise aspects of this project through a spin-out company.

Ethics approval: Ethics approval was not required for the study; however, for a randomised controlled trial, which is ongoing, ethics approval was obtained from the Moorfields and Whittington Research Ethics Committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There are no additional data available.

References

- 1.Westert GP, Faber M. Commentary: the Dutch approach to unwarranted medical practice variation. BMJ 2011;342:d1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wishart GC, Greenberg DC, Chou P, et al. Treatment and survival in breast cancer in the Eastern Region of England. Ann Oncol 2010;21:291–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor C, Munro AJ, Glynne-Jones R, et al. Multidisciplinary team working in cancer: what is the evidence? BMJ 2010;340:c951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lamb BW, Brown KF, Nagpal K, et al. Quality of care management decisions by multidisciplinary cancer teams: a systematic review. Ann Surg Oncol 2011;18:2116–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mazzaferro V, Majno P. Principles for the best multidisciplinary meetings. Lancet Oncol 2011;12:323–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lamb BW, Green JS, Vincent C, et al. Decision making in surgical oncology. Surg Oncol 2011;20:163–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Cancer Peer Review Programme Report 2009/2010. An overview of the findings from the 2009/2010 National Cancer Peer Review of Cancer Services in England. National Cancer Peer Review Programme: National Cancer Action Team, 2010.

- 8.Patkar V, Acosta D, Davidson T, et al. Cancer multidisciplinary team meetings: evidence, challenges, and the role of clinical decision support technology. Int J Breast Cancer 2011;2011:831605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosenbloom ST, Denny JC, Xu H, et al. Data from clinical notes: a perspective on the tension between structure and flexible documentation. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2011;18:181–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Webb SB, Jr, Bracken MB, Wagner FC., Jr Retrospective versus prospective audit: a trial of two methods. Hosp Med Staff 1978;7:13–17 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scott IA, Harper CM. Guideline-discordant care in acute myocardial infarction: predictors and outcomes. Med J Aust 2002;177:26–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peterson ED, Roe MT, Mulgund J, et al. Association between hospital process performance and outcomes among patients with acute coronary syndromes. JAMA 2006;295:1912–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bahtsevani C, Uden G, Willman A. Outcomes of evidence-based clinical practice guidelines: a systematic review. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 2004;20:427–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lara PN, Jr, Higdon R, Lim N, et al. Prospective evaluation of cancer clinical trial accrual patterns: identifying potential barriers to enrollment. J Clin Oncol 2001;19:1728–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bouvier AM, Bauvin E, Danzon A, et al. Place of multidisciplinary consulting meetings and clinical trials in the management of colorectal cancer in France in 2000. Gastroenterol Clin Biol 2007;31:286–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schreiber G, Akkermans H, Anjewierden A, et al. Knowledge Engineering and Management: The Common KADS Methodology. The MIT Press, 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 17.Golbeck J, Fragoso G, Hartel F, et al. The national cancer institutes thesaurus and ontology. J Web Semantics 2003;1:75–80 [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sutton DR, Fox J. The syntax and semantics of the PROforma guideline modeling language. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2003;10:433–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Acosta D, et al. Challenges in delivering decision support systems: the MATE experience. In: Knowledge Representation for Health-Care. Data, Processes and Guidelines. Lecture Notes in Computer Science. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer, 2010:124–40 http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-11808-1_11 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lemieux-Charles L, McGuire W. What do we know about health care team effectiveness? A review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev 2006;63:263–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garg AX, Adhikari NK, McDonald H, et al. Effects of computerized clinical decision support systems on practitioner performance and patient outcomes: a systematic review. JAMA 2005;293:1223–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Campbell NC, Murray E, Darbyshire J, et al. Designing and evaluating complex interventions to improve health care. BMJ 2007;334:455–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choy ET, Chiu A, Butow P, et al. A pilot study to evaluate the impact of involving breast cancer patients in the multidisciplinary discussion of their disease and treatment plan. Breast 2007;16:178–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.