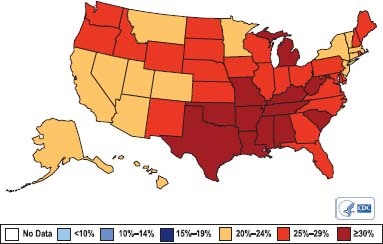

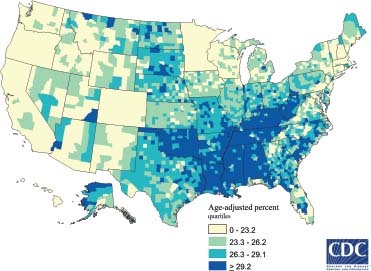

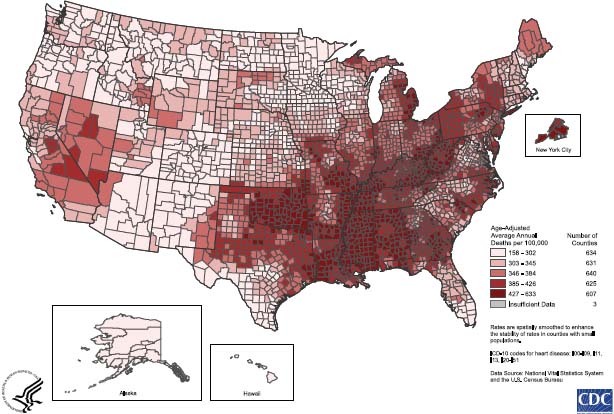

It is well known that obesity and sedentary behavior coexist and that both are associated with cardiovascular disease (CVD) in women. Data from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) show that in areas of the United States where rates of obesity are higher than 30% (Fig. 1), the prevalence of adults who report no leisure-time physical activity is also higher than 30% (Fig. 2). Likewise, the prevalence of obesity and physical inactivity predicts the presence of CVD death (Fig. 3). To highlight the association between the 3 conditions, one can nearly superimpose these 3 maps from the CDC.

Fig. 1 Obesity trends* among U.S. adults. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2010.

*Body mass index ≥30 or ∼30 lbs. overweight for 5′4″ person

Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data

Fig. 2 County-level estimates of leisure-time physical inactivity among adults aged ≥20 years: United States, 2008. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/obesity/data

Fig. 3 United States: heart disease death rates. Women, aged 35+, 2000–2006. Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/dhdsp/maps/national_maps/hd_women.htm

More recently, however, questions have been raised about whether obesity and physical activity are independently associated with CVD risk or if they simply are associated with risk through known risk factors: diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia. If the latter is true, risk reduction with pharmaceutical interventions—in spite of cost, side effects, and incomplete efficacy—might spare providers the difficult task of encouraging weight loss and promoting increases in physical activity. If the former is true, however, weight loss and physical activity are crucial therapies for the prevention of CVD in women.

Obesity and Cardiovascular Disease Risk

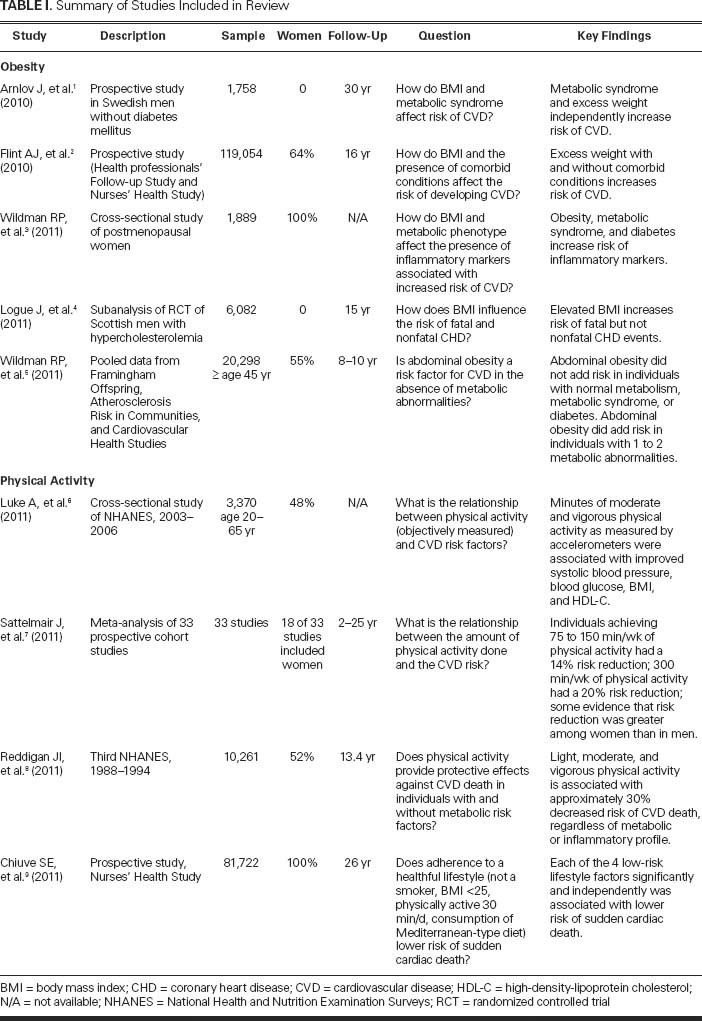

There is abundant evidence that obesity increases the risk of elevated blood sugar, hypertension, and hypercholesterolemia. Similarly, there is ample evidence that weight loss mitigates those risk factors. Several recent studies, however, have explored the question of whether obesity increases the risk of CVD in the absence of other comorbid conditions. Most of the evidence supports obesity as an independent risk factor for CVD in men and women (Table I).1–4 Even in the absence of metabolic abnormalities or comorbid conditions, individuals who are obese have higher rates of cardiovascular events over their lifetimes. One study suggests that the mechanism for this increased risk may be related to the presence, in obese individuals, of elevated inflammatory markers that are associated with CVD.3

TABLE I. Summary of Studies Included in Review

Data that did not fully support obesity as an independent CVD risk factor came from a large study of men and women for whom obesity's effect on CVD seemed to be associated solely with its effect on other metabolic abnormalities.5 Although this well-done analysis might call into question obesity's role in CVD, its follow-up duration (8–10 yr) was shorter than the follow-up of similar studies. Consequently, the results might simply indicate that the cardiovascular effects of obesity are incurred not in the short run, but over decades.

Physical Activity and Cardiovascular Disease Risk

Like the question of obesity, it is important to understand whether physical activity directly reduces CVD risk or if it does so only by lessening other risk factors. Four studies published in 2011 provide evidence that physical activity not only reduces long-known CVD risk factors but reduces CVD risk on its own (Table I).6–9 One study even suggests that the risk reducing benefits of exercise might be more pronounced in women than in men.7 It is of interest that as little as 75 minutes a week of light physical activity could reduce cardiovascular risk by as much as 14%.

Evidence-Based Interventions and Clinical Implications

The evidence described here supports the importance of weight reduction and physical activity in the prevention of CVD in women and men alike. Physicians can and should assist patients in this effort by using evidence-based programs. Two large randomized-control trials provide guidance on strategies and programs that work. The first study is the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP). Individuals who were determined by laboratory testing to be at risk for diabetes were randomized to receive metformin or an intensive lifestyle intervention that promoted calorie control and 150 min/wk of physical activity. Fifty percent of the intensive lifestyle-intervention group lost 7% of their body weight and reduced their risk of developing diabetes over 3 years by nearly 60%, which surpassed the findings in the metformin group.10 The 2nd study compared the effects on CVD risk factors of an intensive lifestyle-intervention program (similar to that of DPP) in diabetic patients to the effects of routine diabetes support and education in a control group. The lifestyle-intervention group, in comparison with the control group, had greater weight loss and significantly greater improvement in blood sugar, blood pressure, and lipids.11 Evidently, these programs accomplished CVD risk reduction not only by preventing or reducing known risk factors, but by reducing weight and increasing activity levels.

Use of these evidence-based programs has become easier for practitioners in two ways: 1) DPP educational materials are free and easy to obtain online, and 2) there are newly implemented community-based DPP programs for at-risk individuals. The DPP program materials can be downloaded at http://www.bsc.gwu.edu/dpp/lifestyle/dpp_part.html and are available in English and Spanish. Moreover, YMCA centers around the country are offering the DPP in the community. Participating centers can be found at http://www.ymca.net/diabetes-prevention.

Conclusions

Weight loss and physical activity independently reduce CVD risk in women and are important tools for prevention and risk reduction for CVD in women. Clinicians can assist patients with lifestyle changes by using the tenets and materials of the Diabetes Prevention Program in their offices or by referring patients to community-based programs at area YMCAs.

Footnotes

Address for reprints: Ann Smith Barnes, MD, MPH, Department of Medicine, One Baylor Plaza, MS 285, Houston, TX 77030

E-mail: smith@bcm.edu

Presented at the 2nd Annual Symposium on Risk, Diagnosis and Treatment of Cardiovascular Disease in Women; Texas Heart Institute, Houston; 1 October 2011.

⋆ CME Credit

References

- 1.Arnlov J, Ingelsson E, Sundstrom J, Lind L. Impact of body mass index and the metabolic syndrome on the risk of cardiovascular disease and death in middle-aged men. Circulation 2010;121(2):230–6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Flint AJ, Hu FB, Glynn RJ, Caspard H, Manson JE, Willett WC, Rimm EB. Excess weight and the risk of incident coronary heart disease among men and women. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2010;18(2):377–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Wildman RP, Kaplan R, Manson JE, Rajkovic A, Connelly SA, Mackey RH, et al. Body size phenotypes and inflammation in the Women's Health Initiative Observational Study. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011;19(7):1482–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Logue J, Murray HM, Welsh P, Shepherd J, Packard C, Macfarlane P, et al. Obesity is associated with fatal coronary heart disease independently of traditional risk factors and deprivation. Heart 2011;97(7):564–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Wildman RP, McGinn AP, Lin J, Wang D, Muntner P, Cohen HW, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk of abdominal obesity vs. metabolic abnormalities. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2011;19(4):853–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 6.Luke A, Dugas LR, Durazo-Arvizu RA, Cao G, Cooper RS. Assessing physical activity and its relationship to cardiovascular risk factors: NHANES 2003–2006. BMC Public Health 2011;11:387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Sattelmair J, Pertman J, Ding EL, Kohn HW 3rd, Haskell W, Lee IM. Dose response between physical activity and risk of coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis. Circulation 2011;124 (7):789–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Reddigan JI, Ardern CI, Riddell MC, Kuk JL. Relation of physical activity to cardiovascular disease mortality and the influence of cardiometabolic risk factors. Am J Cardiol 2011; 108(10):1426–31. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Chiuve SE, Fung TT, Rexrode KM, Spiegelman D, Manson JE, Stampfer MJ, Albert CM. Adherence to a low-risk, healthy lifestyle and risk of sudden cardiac death among women. JAMA 2011;306(1):62–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, Hamman RF, Lachin JM, Walker EA, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med 2002;346(6):393–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Look AHEAD Research Group, Pi-Sunyer X, Blackburn G, Brancati FL, Bray GA, Bright R, et al. Reduction in weight and cardiovascular disease risk factors in individuals with type 2 diabetes: one-year results of the Look AHEAD trial. Diabetes Care 2007;30(6):1374–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]