Abstract

Bleeding is an important predictor of morbidity and mortality rates after the Bentall operation. This study reports our recent experience with composite aortic root replacement via a slightly modified button-Bentall operation.

Fifty-six consecutive patients underwent a Bentall operation on an elective basis from January 2008 through December 2009. In all cases, we used 2 modifications: we imbricated the pledgeted 2-0 polyester interrupted U stitches of the proximal suture line, and at that same suture line we sealed with fibrin glue the possible sources of oozing. The series featured high proportions of associated procedures (25%) and reoperations (23%).

The mean cardiopulmonary bypass and aortic cross-clamp times were 166 ± 50 and 113 ± 27 min, respectively. No case of operative or hospital (30-day) death was observed. Postoperative drainage amounted to 705 mL (median) on the first postoperative day and 377 mL (mean) on the second. Surgical re-exploration for bleeding was needed in only 1 patient (1.8%). Postoperative acute kidney injury was observed in 5 patients, neurologic complications in 3, and respiratory insufficiency requiring prolonged mechanical ventilation in another 3. Both respiratory and renal complications were significantly associated with greater consumption of blood products (P=0.03 and P=0.001, respectively).

We conclude that the combined use of imbricated proximal suture-line stitches and subsequent fibrin-sealant spraying were associated with no deaths and with low rates of bleeding and other adverse postoperative sequelae in our 2-year experience with the Bentall operation in an elective series of patients characterized by a difficult mixture of prognoses.

Key words: Anastomosis, surgical; aorta/surgery; aortic aneurysm/surgery; blood vessel prosthesis implantation; fibrin tissue adhesive;; heart valve prosthesis; hemostasis, surgical/methods; suture techniques; tissue adhesives

The surgical replacement of an aneurysmal aortic root with a valved composite graft was first reported more than 40 years ago, by Bentall and DeBono.1 For coronary artery reattachment, they used in situ circumferential suture lines around the coronary ostia, and to control bleeding they wrapped the native aortic wall around the prosthesis.

In response to evidence of increased risk of pseudoaneurysm development and of coronary compression or detachment due to oozing within the perigraft space, technical variations, such as the Cabrol modification,2 have been introduced; however, the Cabrol carries the risk of thrombosis of the interposed Dacron conduits. The most commonly performed variant for root replacement today is the “button” technique of Kouchoukos and colleagues.3 This method has proved effective in avoiding tension on the coronary anastomoses, thereby preventing excessive bleeding and kinking of the coronary arteries.

However, bleeding is still the main concern in this type of surgery. It is true that the initially reported unacceptably high rates of intra- and postoperative hemorrhage4,5 have been reduced by increased operative experience, graft preclotting, improvements in pump oxygenators, and the use of Teflon for aortic stump reinforcement. Yet early mortality and noncardiac morbidity rates are still higher than for other cardiac surgical procedures, and these rates correlate closely with excessive bleeding during operation.4,6,7 In a recent series of more than 250 patients who underwent surgery during a 15-year period,8 there was a significant association between reclamping for intraoperative bleeding and the main determinants of hospital death (that is, postoperative low-cardiac-output syndrome [P=0.018] and pulmonary complications [P=0.001]). In this regard, bleeding risk also explains the marked difference between Bentall results when elective surgery (for chronic root aneurysm) is performed, versus emergent surgery (for aneurysm rupture or dissection). The emergent procedure is characterized by greater rates of potentially fatal pulmonary and cardiac complications.9

In the present retrospective, observational study, we report our experience in a 2-year series of electively performed modified button-Bentall operations, in which we used both fibrin sealant and imbricated U stitches for the proximal anastomosis. Thereby, we focused on reducing perioperative bleeding and improving in-hospital outcomes.

Patients and Methods

From January 2008 through December 2009, we performed the Bentall procedure in 85 consecutive patients, 29 of whom were excluded from the present analysis because they underwent composite root replacement for acute aortic diseases (aneurysm rupture in 1, type A dissection in 28). The other 56 patients (8 women; mean age, 59 ± 13 yr) constituted the present study population, undergoing elective modified Bentall operations for aortic root aneurysm with aortic valve dysfunction. Five patients (9%) had Marfan syndrome and 9 (16%) had congenital bicuspid aortic valve. Severe aortic regurgitation was present in 47 patients (84%); in 2 patients (4%), this condition was due to endocarditis. Three patients (5%) had mixed stenosis and regurgitation, and 6 (11%) had undergone a previous aortic valve replacement. The procedure was a reoperation in 13 of the 56 cases (23%): 6 patients had undergone a previous aortic valve replacement operation (3 isolated, 1 associated with replacement of the supracoronary aorta, 1 with ascending aortoplasty, and 1 with coronary artery bypass grafting [CABG]); 5 had a previous repair of type A aortic dissection with ascending aorta replacement and aortic valve resuspension; and 2 had a previous mitral valve replacement. The Bentall operation was associated with other procedures in 14 cases (25%): CABG in 8, hemiarch or total arch replacement in 4, hemiarch plus CABG in 1, and mitral valve replacement in 1.

Surgical Technique

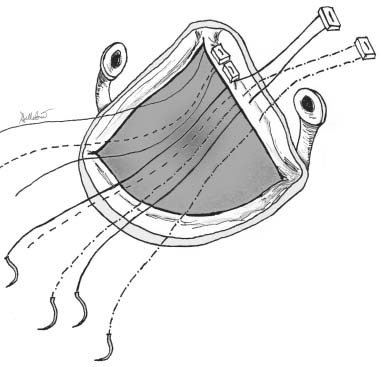

All surgical approaches were through a median sternotomy, and all operations were performed with the aid of cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) instituted by means of atrial drainage and cannulation of the distal ascending aorta (in most cases) or the femoral or right axillary artery for arterial return. We instituted moderate hypothermia and infused cold cardioplegic solution either antegrade (directly into the coronary ostia) or retrograde (into the coronary sinus)—or both. Composite conduits were implanted by means of the same technique throughout the study period: after excision of the native valve and preparation of the coronary buttons, an adequate-size valved Dacron graft was sutured to the ventriculo-aortic junction with pledgeted 2-0 polyester interrupted U sutures. Models included were the Carbomedics Carbo-Seal® (Sorin USA; Arvada, Colo) in 47 patients, the Hemashield® (Boston Scientific Corporation; Natick, Mass) in 7, the AlboGraft™ (LeMaitre Vascular, Inc.; Burlington, Mass) in 1, and a Dacron graft (Datascope Intervascular, now part of Maquet Cardiovascular, LLC; Wayne, NJ) in 1. To obtain better hemostasis of the proximal anastomosis, each suture was imbricated—that is, the first stitch of the second U suture was passed between the 2 stitches of the previous U suture, taking bites slightly larger than usual, and so on (Fig. 1). Coronary buttons were attached to the graft by means of continuous 5-0 polypropylene sutures without Teflon felt pledgets, and then the distal anastomosis was performed with a running 5-0 or 6-0 polypropylene suture. Before aortic clamp removal, we sprayed autologous or (in the last months of this experience) homologous fibrin sealant through a spray-pen applicator at all suture sites. After rewarming and air evacuation, the patients were weaned from CPB.

Fig. 1 Schematic representation of the imbricated U stitch technique used in the present series to obtain hemostatic proximal suture in elective modified Bentall operations. The aortic root has been excised and the coronary ostia prepared. Four consecutively passed pledgeted sutures are represented as continuous, dashed, bold, and dashed-dotted lines.

Fibrin-Sealant Preparation

In the first months of this experience, on the day of operation, 120 mL of blood was withdrawn just before each patient entered the operating room. The blood bank of our hospital then prepared autologous fibrin glue by using the Vivostat® system (Vivostat A/S; Alleroed, Denmark), including a processor unit, for automatic and microprocessor-controlled elaboration of blood via batroxobin-enhancing human fibrinogen conversion to fibrin by endogenous thrombin; the thrombin was then removed by filtration, to obtain the final fibrin product. This preparation lasted 30 minutes on average. During the last months, we prepared fibrin glue from homologous frozen Plasmasafe plasma (Torrinomedica; Rome, Italy). An automatic applicator unit was used to store and transport the fibrin sealant to the operating room, and a disposable spray-pen kit was used to apply the sealant to the suture lines. The spray-pen provided the surgeon with 7 minutes of total irrigation (5 mL of sealant). Care was taken to avoid application to wet surfaces, both by aspirating liquid and by applying gauzes before spraying the glue.

Statistical Analysis

This was a retrospective, observational study: perioperative and 30-day data were collected by review of hospital and outpatient charts. Considered variables included demographics and anthropometrics, relevant preoperative comorbidities, previous cardiac operations, New York Heart Association functional class, valve function variables, type of prosthesis implanted, cross-clamp and CPB times, associated procedures, postoperative complications, and durations of stay in the hospital and intensive care unit. Outcomes included hospital morbidity and mortality rates, with particular focus on postoperative hemorrhage, respiratory, renal, and neurologic complications. In order to compare subgroups at different risks for bleeding (for example, patients receiving deep hypothermic arrest and reoperative patients) with the remaining part of the study cohort, we applied the Student t test for normally distributed continuous variables (CPB and cross-clamp times, 2nd-day drainage amount; summarized as mean ± SD) and the Mann-Whitney U test for asymmetrically distributed variables (1st-day drainage amount, blood products received; summarized as median and interquartile range [IQR]). Significance was set at 5% probability of the null hypothesis.

Results

Comorbidities

In our analysis of these patients' baseline characteristics, we found hypertension in 80% of patients, diabetes mellitus in 16%, dyslipidemia in 23%, coronary artery disease in 16%, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in 23%, chronic renal failure in 7%, and chronic hepatitis C virus infection in 9%.

Operative Outcomes

In regard to intraoperative results, mean CPB time and aortic cross-clamp times were 166 ± 50 and 113 ± 27 min, respectively. The use of imbricated sutures did not increase cross-clamp time in comparison with our previous use of a conventional suturing technique (data not shown). It is noteworthy that in the reoperative cases CPB was usually started retrograde through the femoral artery and vein, before mediastinal reopening. The most often used size of prosthetic valve was 23 mm (39%), followed by 25 mm (34%), 27 mm (20%), and 26 and 28 mm (1.8% each). All 5 patients in whom the aortic arch was replaced underwent deep hypothermic circulatory arrest (DHCA) with the Kazui technique for antegrade selective cerebral perfusion (mean lowest temperature reached, 22 ± 0.6 °C); their average circulatory arrest time was 30 ± 9 min. In only 1 instance was aortic reclamping necessary to control bleeding from the distal suture line.

No intraoperative death was observed. One patient developed low-cardiac-output syndrome during weaning from CPB, but it was successfully managed by intra-aortic balloon pumping and the infusion of inotropic agents. No bleeding was observed at the proximal anastomosis, which had been sutured and sealed in the manner described herein.

Postoperative Outcomes

In regard to postoperative results, no case of hospital death (≤ 30 days) was recorded. The mean duration of intensive care unit stay was 4 ± 3 d, while the mean duration of hospital stay was 13 ± 6 d.

The total postoperative drainage amount was 705 mL (median; interquartile range, 555–922 mL) in the 1st postoperative day and 377 mL (mean, ± 212 mL) in the 2nd day. Surgical re-exploration for bleeding was needed in only 1 patient (1.8%), who had manifested abnormal bleeding during the first 2 postoperative hours (then had reached a total of 1,590 mL at the end of the first 24 hr). This patient had previously undergone ascending aorta replacement for type 1 acute aortic dissection and had a history of chronic hepatic disease; on the present occasion, he underwent the Bentall operation and bypass of the left anterior descending coronary artery with a left internal mammary artery graft. No discrete surgical bleeding source was found at re-exploration, and bleeding decreased to normal values after clot removal from the pericardium and the patient's re-entry into intensive care.

In regard to postoperative events other than bleeding, 1 patient experienced severe acute renal failure that required a period of continuous venovenous hemofiltration, but this was followed by recovery of renal function and stabilization of the serum creatinine level. Another 4 patients had transient renal injury that resolved spontaneously. Neurologic complications occurred in 3 patients (2 had transient deficits and 1 experienced a stroke). These patients had undergone isolated Bentall operations (2 patients) or Bentall plus double CABG (1 patient), all 3 without circulatory arrest. Three patients had respiratory complications that required prolonged mechanical ventilation (1 patient also underwent a tracheostomy).

The 3 patients with respiratory complications had received significantly greater total amounts of blood products than did the remaining study population (median, 19 units [IQR, 9–46] vs 5 units [IQR, 0–13]; P=0.03). Similarly, the 5 patients who experienced kidney injury received more units of blood than did the others (median, 26 units [IQR, 18–46] vs 7 units [IQR, 0–13]; P=0.001). In none of the patients with neurologic problems was an embolic cause found by means of computed tomography, which test result was negative in the 2 patients with transient deficit, but led to a diagnosis of diffuse hypoperfusion and hypoxia in the 3rd patient.

When reoperative patients were compared with 1st-operation patients, a significant difference was observed in CPB time (212 ± 71 vs 153 ± 31 min; P=0.012), but not in cross-clamp time (110 ± 32 vs 113 ± 26 min; P=NS). Significant differences between these 2 groups were also observed in mean total drainage (1st postoperative day (median, 750 mL [IQR, 575–1,140 mL] vs median, 700 mL [IQR, 545–900 mL]; P=0.60) and in blood-product consumption (fresh frozen plasma, 4 units [IQR, 2–6] vs 3 units [IQR, 0–5], P=0.12; and platelets, 4 units [IQR, 0–11] vs 0 [IQR, 0–6], P=0.08). The exception was red blood cells (2 units [IQR 1–4] vs 0 [IQR 0–2]; P=0.001), mainly due to differences in the intraoperative administration of red blood cells.

When patients receiving hemiarch replacement under DHCA were compared with the others, CPB time was not significantly longer (200 ± 41 vs 163 ± 50 min; P=0.16): this subgroup did not have significantly different drainage amounts (1st postoperative day: median, 725 mL [IQR, 500–1,190] vs 705 mL [IQR 555–922]; P=NS) or blood-product requirements (all P=NS).

Discussion

After the introduction of the “button” technique,3 preventing early and late coronary distortion or kinking, the results of the Bentall procedure greatly improved. Consequently, bleeding at the level of the proximal anastomosis remains the main problem, especially when the posterior aortic circumference is involved. That portion of the aorta is almost impossible to reach after completion of the procedure, and mobilizing the graft after left main coronary artery anastomosis is a high-risk maneuver.

Recently, many modifications of the original technique have been proposed to prevent the problem. Copeland and colleagues10 used a tandem-suture-lines technique, with interrupted mattress sutures to anchor the prosthesis to the aorto-ventricular junction and a running suture between the prosthesis and the remnants of the supra-annular aortic wall. Khanna and Akhter11 proposed a purse-string suture reinforced with Teflon pledgets through the aortic wall above the proximal suture line. Mohite and associates12 recently reported their experience with the use of interrupted pledgeted everting mattress sutures at the proximal anastomosis, passed through the sewing cuff of the valved conduit and then through an autologous pericardial strip. Chen and colleagues13 used a prosthesis that was modified with a short skirt of Dacron attached to the sewing cuff, which was sutured to the remaining proximal aortic tissue—thereby forming a peri-anastomotic space that is then filled with fibrin glue. Most of the cited authors simply described their techniques to prevent or control bleeding during Bentall procedures, without describing any series or reporting any short-term result.

Conversely, this present paper reports the excellent in-hospital outcomes of a consecutive series of patients who underwent the Bentall procedure with the technical hemostatic variant of imbricated proximal interrupted sutures and fibrin-sealant application. Although small, the study cohort was both homogeneous (patients who underwent surgery on an emergency basis were excluded) and representative of patients in a real tertiary cardiac surgery referral center today. High proportions of our patients presented with important comorbidities that often required associated procedures (Bentall plus CABG, for example), and nearly one quarter had a history of previous cardiac operation. Therefore, we believe that the analysis of short-term outcomes reported here is clinically important.

Compared with the previously proposed hemostatic modifications of the proximal anastomosis,10–13 our technique does not call for the use of additional material or adjunctive sutures, which can lengthen cross-clamp and CPB times, potentially canceling the effect of the technical modification itself by impairing coagulation and promoting postoperative morbidity. In the present series, we had CPB and cross-clamp times comparable to those of our previous routine experience with the Bentall operation in the absence of imbricating sutures. No peri-anastomotic space is created; instead, the proximal suture line is left visible, so that possible sources of bleeding can be detected and controlled. In our experience, residual oozing from the proximal suture line was successfully prevented by the topical spraying of fibrin sealant before clamp removal.

The hemostatic effectiveness of fibrin glue has been widely demonstrated, first in peripheral vascular surgery and thereafter in cardiac and aortic surgery.14,15 The absence of potentially toxic components, such as glutaraldehyde, makes this type of surgical glue the safest option available. We have seen warnings that one possible drawback of the use of fibrin sealant (as well as any other type of surgical glue) is the risk of penetration between the stitches of the suture lines and consequent systemic embolization after flow has been restarted.16 However, the use of imbricated sutures for proximal anastomosis virtually eliminates the spaces between stitches, which makes sealant penetration at that level of the aortic lumen unlikely.

Our results (most notably, no early deaths and a very low bleeding-complication rate among 56 patients) were satisfactory when compared with other authors' results (death rates ranging from 2% to 11% among elective patients17–19), especially considering the high-risk population included in our study group. Also our 1.8% rate of hemorrhagic complication compares favorably to those reported in recent papers on elective Bentall procedures, which average 9% to 10%.8,9 The present results are an improvement over our previous experience in this setting: in the 62 consecutive elective composite root replacements performed during the preceding 3 years, bleeding that necessitated reopening the sternum occurred at a rate of 8% (5 patients). At that time, we used neither of the 2 technical expedients here introduced.

Limitations. We must acknowledge several limitations to our study. First, the low mortality and morbidity rates could have been a result of correct perioperative management, rather than imbricated sutures and fibrin sealant. However, it has been widely recognized that, regardless of perioperative methods, bleeding and bleeding-related complications (encompassing surgical re-exploration, massive blood-product transfusion, hemorrhagic shock, secondary coagulopathy, and systemic inflammatory reaction) are among the major determinants of early death and relevant morbidity in aortic root surgery.4–9 Therefore, it can be argued that our low rate of bleeding and related complications accounts for our low rates of death and organ morbidity. Another limitation is that the specific role of each of the 2 technical expedients applied in the present series cannot be isolated, because they were both used in all patients. Our belief that the 2 methods complement each other—confronting 2 different mechanisms of surgical hemorrhage (suture-line bleeding and needle-hole oozing)—overcame our wish for investigational purity. Finally, we had no control group to undergo the Bentall procedure without imbricated sutures and fibrin sealant. The present study, with its small numbers, is intended as a descriptive report of a pilot experience; for a formal comparison, a larger series must be cumulated, in order to provide the required statistical power for matched comparisons.

Conclusion. These limitations notwithstanding, we conclude that the combined use of imbricated proximal suture-line stitches and subsequent fibrin-sealant spraying was associated with no deaths and with low rates of bleeding and other adverse postoperative sequelae in our 2-year experience with the Bentall operation—this in an elective series of patients characterized by a difficult mixture of prognoses.

Footnotes

Address for reprints: Alessandro Della Corte, MD, PhD, Department of Cardiovascular Surgery & Transplant, V. Monaldi Hospital, Via L. Bianchi, 80131 Naples, Italy

E-mail: aledellacorte@libero.it

References

- 1.Bentall H, De Bono A. A technique for complete replacement of the ascending aorta. Thorax 1968;23(4):338–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Cabrol C, Pavie A, Gandjbakhch I, Villemot JP, Guiraudon G, Laughlin L, et al. Complete replacement of the ascending aorta with reimplantation of the coronary arteries: new surgical approach. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1981;81(2):309–15. [PubMed]

- 3.Kouchoukos NT, Wareing TH, Murphy SF, Perrillo JB. Sixteen-year experience with aortic root replacement. Results of 172 operations. Ann Surg 1991;214(3):308–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Gott VL, Gillinov AM, Pyeritz RE, Cameron DE, Reitz BA, Greene PS, et al. Aortic root replacement. Risk factor analysis of a seventeen-year experience with 270 patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1995;109(3):536–45. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Asano KI, Ando T, Hanada S, Maruyama Y. Control of bleeding during the Bentall operation. J Cardiovasc Surg (Torino) 1983;24(1):13–4. [PubMed]

- 6.Baumgartner WA, Cameron DE, Redmond JM, Greene PS, Gott VL. Operative management of Marfan syndrome: The Johns Hopkins experience. Ann Thorac Surg 1999;67 (6):1859–60. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Sokullu O, Sanioglu S, Orhan G, Kut MS, Hastaoglu O, Karaca P, et al. New use of Teflon to reduce bleeding in modified Bentall operation. Tex Heart Inst J 2008;35(2):147–51. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Mataraci I, Polat A, Kiran B, Caliskan A, Tuncer A, Erentug V, et al. Long-term results of aortic root replacement: 15 years' experience. Ann Thorac Surg 2009;87(6):1783–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Apaydin AZ, Posacioglu H, Islamoglu F, Calkavur T, Yagdi T, Buket S, Durmaz I. Analysis of perioperative risk factors in mortality and morbidity after modified Bentall operation. Jpn Heart J 2002;43(2):151–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Copeland JG 3rd, Rosado LJ, Snyder SL. New technique for improving hemostasis in aortic root replacement with composite graft. Ann Thorac Surg 1993;55(4):1027–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Khanna SK, Akhter M. Hemostatic modification in aortic root replacement with composite graft. Ann Thorac Surg 1995;60(4):1161–2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Mohite PN, Thingnam SK, Puri S, Kulkarni PP. Use of pericardial strip for reinforcement of proximal anastomosis in Bentall's procedure. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2010; 11(5):527–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Chen LW, Dai XF, Wu XJ. A modified composite valve Dacron graft for prevention of postoperative bleeding from the proximal anastomosis after Bentall procedure. Ann Thorac Surg 2009;88(5):1705–7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Kram HB, Nugent P, Reuben BI, Shoemaker WC. Fibrin glue sealing of polytetrafluoroethylene vascular graft anastomoses: comparison with oxidized cellulose. J Vasc Surg 1988; 8(5):563–8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Seguin JR, Picard E, Frapier JM, Chaptal PA. Repair of the aortic arch with fibrin glue in type A aortic dissection. J Card Surg 1994;9(6):734–9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Carrel T, Maurer M, Tkebuchava T, Niederhauser U, Schneider J, Turina MI. Embolization of biologic glue during repair of aortic dissection. Ann Thorac Surg 1995;60(4):1118–20. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Bachet J, Termignon JL, Goudot B, Dreyfus G, Piquois A, Brodaty D, et al. Aortic root replacement with a composite graft. Factors influencing immediate and long-term results. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 1996;10(3):207–13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Michielon G, Salvador L, Da Col U, Valfre C. Modified button-Bentall operation for aortic root replacement: the miniskirt technique. Ann Thorac Surg 2001;72(3):S1059–64. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Baraki H, Al Ahmad A, Sarikouch S, Koigeldiev N, Khaladj N, Hagl C, et al. The first fifty consecutive Bentall operations with a prefabricated tissue-valved aortic conduit: a single-center experience. J Heart Valve Dis 2010;19(3):286–91. [PubMed]