Abstract

Gd-LC6-SH is a thiol-bearing DOTA complex of gadolinium designed to bind plasma albumin at the conserved Cys34 site. The binding of Gd-LC6-SH shows sensitivity to the presence of competing thiols. We hypothesized that Gd-LC6-SH could provide magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) enhancement that is sensitive to tumor redox state and that the prolonged retention of albumin-bound Gd-LC6-SH in vivo can be exploited to identify a saturating dose above which the shortening of MRI longitudinal relaxation time (T1) of tissue is insensitive to the injected gadolinium dose. In the Mia-PaCa-2 pancreatic tumor xenograft model in SCID mice, both the small-molecule Gd-DTPA-BMA and the macromolecule Galbumin MRI contrast agents produced dose-dependent decreases in tumor T1. By contrast, the decreases in tumor T1 provided by Gd-LC6-SH at 0.05 and 0.1 mmol/kg were not significantly different at longer times after injection. SCID mice bearing Mia-PaCa-2 or NCI-N87 tumor xenografts were treated with either the glutathione synthesis inhibitor buthionine sulfoximine or the thiol-oxidizing anticancer drug Imexon, respectively. In both models, there was a significantly greater increase in tumor R1 (=1/T1) 60 minutes after injection of Gd-LC6-SH in drug-treated animals relative to saline-treated controls. In addition, Mercury Orange staining for nonprotein sulfhydryls was significantly decreased by drug treatment relative to controls in both tumor models. In summary, these studies show that thiol-bearing complexes of gadolinium such as Gd-LC6-SH can serve as redox-sensitive MRI contrast agents for detecting differences in tumor redox status and can be used to evaluate the effects of redox-active drugs.

Introduction

In mammalian cells, response to oxidative stress is brought about by the NRF2 transcription factor that triggers the transactivation of genes that contain at least one antioxidant response element in their promoters. These include genes encoding for the glutamate-cysteine ligase catalytic and modifier subunits, which catalyze the rate-limiting step in glutathione synthesis, as well as genes that encode for proteins such as glutathione reductase, thioredoxin, thioredoxin reductase, peroxiredoxin, and sulfiredoxin, which are required for restoring oxidized intracellular thiols to their reduced states [1]. Reduced glutathione (GSH) accounts for more than 90% of nonprotein thiols in cells; is a tripeptide of glutamate, cysteine, and glycine;and is synthesized intracellularly by the consecutive actions of γ-glutamylcysteine synthetase (γ-GCS) and glutathione synthetase. Feedback inhibition of γ-GCS by the final product GSH results in this step becoming rate limiting for de novo intracellular synthesis of GSH [2]. GSH is involved in the detoxification of xenobiotics, including chemotherapeutics, by conjugation of electrophilic groups on the molecule with the nucleophilic sulfhydryl of GSH. These can be nonenzymatic reactions or conjugations catalyzed by glutathione-S-transferase and GSH peroxidase. Conjugation negatively impacts the antitumor activities of platinum drugs, nitrogen mustards, doxorubicin, and nitrosoureas [3]. Detoxification of electrophilic drugs can also occur in the extracellular space through the action of plasma membrane-bound γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (γ-GT), another enzyme regulated by NRF2, on extracellular GSH [4]. Drugs such as Imexon and 2-deoxy-glucose have been reported to produce oxidative stress in cultured cells by decreasing intracellular concentrations of reduced glutathione and cysteine [5–7]. These disruptions in thiol metabolism have been reported to radiosensitize cultured tumor cells and xenograft tumor models [7,8], effects that could be augmented by concomitant use of the γ-GCS inhibitor l-buthionine-SR-sulfoximine (BSO) [5] or mitigated by concomitant use of the thiol antioxidant N-acetylcysteine [5,7]. Although N-acetylcysteine remains extracellular, it is thought to affect scavenging of intracellular reactive oxygen species produced by ionizing radiation by increasing intracellular GSH [9]. Elevated GSH concentrations have also been reported to comprise one of the mechanisms of tumor cell resistance to cyclophosphamide, and this resistance could be abolished in cultures by treating the tumor cells with BSO [10].

There is, therefore, much interest in the development of methods to selectively modify tumor redox status to therapeutic advantage [3,11]. Tissue redox status is also important in other pathologies, including aging, diabetes mellitus, and cardiovascular, inflammatory, immune, and neurodegenerative diseases. A perturbed redox balance is also a hallmark of several fibrotic diseases, and GSH and N-acetylcysteine have been used clinically for the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and cystic fibrosis [12,13]. Although the extracellular GSH pool is small, the redox potential of the GSSG/GSH pool has been measured to be more reducing than other thiol-disulfide couples in plasma, and it has been suggested that GSH provides the reducing equivalents to maintain the redox states of other thiol pools [14]. GSH is made in cells and is readily transported out to the extracellular space; current evidence indicates a role for the multidrug resistance-associated proteins (MRP/ABCC) in the export of GSH as well as oxidized glutathione (GSSG), glutathione S-conjugates, and GSH adducts formed in response to oxidative or electrophilic challenge [13]. NRF2 control of the expression of MRP and γ-GT [1] provides cells with the ability to control both intracellular and extracellular redox states in response to oxidative stress.

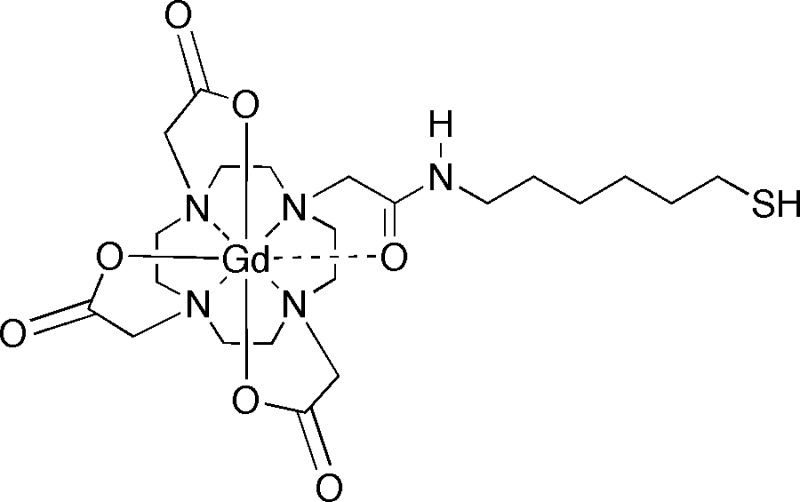

Biomedical imaging methods for interrogating spatial variations in redox status within tumors would be desirable for their relatively noninvasive nature, especially when the target tissue is not readily amenable to biopsy. Opstad et al. [15] have quantified GSH in meningiomas with localized 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) in a clinical setting, although the insensitivity of MRS limits the spatial resolution of the technique. Thelwall et al. [16] have used 1H-decoupled 13C MRS imaging to follow the incorporation of exogenously infused 13C-labeled glycine into glutathione in tumor-bearing rats. The disadvantages of their technique include the need for very long infusions with 13C-labeled substrate, as well as long imaging times to achieve relatively coarse image resolutions. Nonetheless, these methods offer a window into in vivo glutathione metabolism. Nitroxide radicals, because of their ability to participate in redox reactions, have been used as spin probes in electron paramagnetic resonance spectroscopy and imaging to monitor in vivo redox status [17]. The conversion of paramagnetic nitroxyl radicals to diamagnetic hydroxylamine molecules in reducing microenvironments in tissue can also be observed as a decrease of signal in T1-weighed magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [18]. Whether imaged by electron paramagnetic resonance or MRI, nitroxide concentrations can be used to monitor tissue redox status in vivo because the rate of disappearance of the nitroxide signal is dominated by chemical reduction rather than clearance from the animal [19]. The nitroxide doses used in these measurements are typically in the range of 0.75 to 1.5 mmol/kg, and nitroxide-enhanced MRI has recently been used to produce spatial maps of bioreductive activity in multiple tissues and organs in mice [20]. Gadolinium-based MRI contrast agents possess longitudinal water-proton relaxivities (r1) that are an order of magnitude or more greater than the r1 of nitroxide radicals, allowing the use of proportionately smaller doses in MRI studies. Tu et al. [21] have described a combination of a spiropyran group and a Gd-DO3A complex that exhibits an r1 that is sensitive to NADH. We have reported the development of thiol-bearing DOTA complexes of gadolinium designed to bind plasma albumin at the conserved Cys34 site. The in vitro binding affinities of these complexes with human serum albumin were studied using homocysteine, an endogenous thiol known to bind to the Cys34 site in plasma albumins [22]. One of these complexes, Gd-LC6-SH (Figure 1), demonstrated prolonged retention in mice after intravenous administration, and this in vivo retention could be released by chasing with homocysteine [23]. In the present work, we have used the albumin binding of this complex to identify a “saturating” dose, above which changes in tumor longitudinal relaxation time (T1) at longer times after injection were insensitive to the injected dose. The r1 of Gd-LC6-SH is higher when the complex is bound to albumin compared with the unbound molecule. We have therefore hypothesized that the change in tumor T1 (ΔT1) produced by Gd-LC6-SH injected at the saturating dose will be dependent on the local concentration of thiols capable of competing for binding albumin at Cys34; a smaller ΔT1 would be expected in highly reducing regions compared with that in oxidizing regions. We have compared the ΔT1 of Mia-PaCa-2 xenografts in mice treated with saline or BSO, and NCI-N87 tumor xenografts in mice treated with saline or Imexon, and have correlated differences in MRI results with treatment-related changes in tumor thiol content. In both models, there was a significantly greater increase in tumor R1 (=1/T1) 60 minutes after injection of Gd-LC6-SH in drug-treated animals relative to saline-treated controls. In addition, Mercury Orange staining for nonprotein sulfhydryls (NPSHs) was significantly decreased by drug treatment relative to controls in both tumor models. Multidose Imexon treatment also produced a tumor growth delay in NCI-N87 tumors relative to saline-treated controls.

Figure 1.

The Gd-LC6-SH compound.

Materials and Methods

Mice, Tumors, and Drugs

All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Arizona. Mia-PaCa-2 pancreatic carcinoma cells and NCI-N87 gastric carcinoma cells were obtained from the ATCC (Manassas, VA). Tumor cells were established as xenografts on the flanks of 4-week-old female SCID mice by the Experimental Mouse Shared Service of the Arizona Cancer Center. For MRI contrast agent characterization studies, mice were imaged when tumors were 150 to 1100 mm3 as estimated by orthogonal caliper measurements. In the first drug study, mice were randomized to control (saline) or BSO groups when Mia-PaCa-2 tumors were 172 ± 83 mm3. BSO (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) was prepared as a 250-mM solution at pH 7.4 in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Mice were administered either BSO (5 mmol/kg, i.p.) or saline (0.5 mL per 25 g, i.p.) on day 1, followed by a second dose 4 hours before MRI on day 2, and a third dose 4 hours before sacrifice and harvest of tumors on day 3. In the second drug study, mice were randomized to control (saline) or Imexon groups when NCI-N87 tumors were 111 ± 44 mm3. Imexon (Amplimexon; AmpliMed Corp, Tucson, AZ) was prepared as a 15-mg/ml solution, and mice were administered either Imexon (150 mg/kg, i.p.) or saline (0.25 ml per 25 g, i.p.) 2 hours before MRI on day 1, followed by a second dose 2 hours before sacrifice and harvest of tumors on day 2. In the third drug study, 48 mice bearing NCI-N87 tumors were administered either Imexon (150 mg/kg, i.p.) or saline (0.25 ml per 25 g, i.p.) on days 5, 9, and 13 after inoculation. Twelve mice (six with saline + six with Imexon) were used in a substudy to follow tumor volumes for 39 days. Twenty-four mice (12 with saline + 12 with Imexon) were used in a substudy to assess tumor thiols by histologic staining with Mercury Orange; these tumors were harvested 2 hours after dosing on day 13 (vide infra). The remaining 12 mice (6 with saline + 6 with Imexon) were imaged by MRI, with the dose on day 13 being administered 2 hours before imaging.

MRI Contrast Agents

Gd-LC6-SH was synthesized as detailed previously [22,23]. Gd-LC6-SH and Gd-DTPA-BMA (OmniScan; GE Healthcare, Princeton, NJ) were prepared as 25- and 50-mM solutions in PBS at pH 7.4. Galbumin (BioPAL, Inc, Worcester, MA) is a macromolecule comprising several Gd-DTPA molecules covalently attached to bovine serum albumin (BSA) and was purchased as a solution, which was 1.76 mM in terms of BSA and 31.2 mM in terms of Gd. Before in vivo use, this solution was diluted with PBS to produce solutions that were 7.8 and 15.6 mM in Gd at pH 7.4.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

All MRI measurements were made on a Bruker Biospec MR imager with a 7-T horizontal bore magnet equipped with 600 mT/m self-shielded gradients (Bruker Biospin, Billerica, MA). Mice were anesthetized using isoflurane (1.5% in O2, 1 L/min) and cannulated at the tail vein for injections. A pressure transducer pad for monitoring respiration (SA Instruments, Inc, Stony Brook, NY) was placed under the anesthetized animal, and the mouse was gently secured in a plastic holder. The animal was loaded into a 25-mm-ID small animal imaging Litz coil (Doty Scientific, Columbia, SC), and the entire assembly was centered inside the MRI magnet. Animal body temperature was maintained using a forced warm air system and monitored using a rectal temperature probe (SA Instruments). After acquisition of scout MRI images, eight gradient-echo (GRE) images were acquired using the following parameters at a scan time of 80 seconds per image: repetition time (TR) = 78 milliseconds, echo time (TE) = 3.5 milliseconds, matrix = 256 x 256, field of view = 3 x 3 cm, slice thickness = 2 mm, number of averages (NA) = 4, and eight varying flip angles ranging from 5° to 75°. These images were used for calculating a precontrast T1 map and proton density map. This was followed by a coregistered dynamic GRE series (TR = 78 milliseconds, TE = 3.5 milliseconds, flip angle = 75°, NA = 1, number of repetitions = 60, scan time = 20 minutes) during which the contrast medium was administered. After the start of the dynamic series, contrast agent solution was administered as a tail vein injection at the appropriate dose for 1 minute and chased with 0.15 ml of saline injected over 1 minute. After the dynamic series, 10 coregistered GRE images (TR = 78 milliseconds, TE = 3.5 milliseconds, flip angle = 75°, NA = 12) were acquired at regular intervals to 60 minutes after injection of the contrast agent. Together with the precontrast proton density map, these 10 postcontrast T1-weighted images were used to compute postcontrast T1 maps at the 10 time points after injection of gadolinium.

Tissue Sections

Mercury Orange (1-[4-chloromercuriophenylazo]-2-naphthol) is a histochemical stain for thiols. Over the years, several groups have optimized solvent, exposure time, and temperature conditions to improve selectivity for NPSHs over protein sulfhydryl groups and other macromolecules and lipids [24–27]. Hedley et al. [28] report good agreement between NPSH values determined by a high-performance liquid chromatography method and NPSH quantified by fluorescence image analysis of cryostat sections of clinical tumor biopsies stained with Mercury Orange. Tumor sections were cut, fixed, stained, and mounted on slides by the Tissue Acquisition and Cellular/Molecular Analysis shared service of the Arizona Cancer Center as per the method of Hedley et al. [28]. Briefly, tumors were rapidly harvested from mice after sacrifice by cervical dislocation under anesthesia (4% isoflurane in O2). This was done the day after imaging to allow for complete clearance of Gd-LC6-SH from the animals. Harvested tumors were immediately placed into cryovials containing Tissue-Tek OCT embedding medium (Sakura Finetek USA, Torrance, CA) and frozen in isopentane immersed in liquid nitrogen. Serial sections of tumor tissue (3µm) were cut using a Microm HM550 Cryostat (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA), and two tissue sections were picked up on charged slides (SuperFrost Plus charged microscope slides, no. 48311-703, VWR, Arlington Heights, IL). One section was stained with freshly prepared Mercury Orange (Sigma-Aldrich) on ice. Mercury Orange was dissolved in acetone, and ultra pure water was added to produce a 75-µM solution in 9:1(vol/vol) acetone-water. Cut sections were rapidly placed in the Mercury Orange solution and stained on ice for 5 minutes. This was followed by two rinses with 9:1 acetone-water on ice and a final rinse with PBS, after which the slides were coverslipped with a glycerol-based nonfluorescent medium (no. 475904, Mowiol 4-88, EMD Millipore, San Diego, CA). The second tissue section was fixed in acetone, rinsed, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E).

Mercury Orange Control Experiment

In a separate experiment, serial sections of a Mia-PaCa-2 tumor were cut and picked up on slides as described above, after which the slides were immersed for 20 minutes at room temperature in either PBS, PBS containing 4 mM 5,5′-dithiobis-(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB), or PBS containing 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT). After this incubation, four sections from each condition were stained with Mercury Orange as described above, whereas additional two sections incubated in PBS for 20 minutes were stained with H&E.

Light Microscopy

H&E-stained slides were imaged at 200x on a DMetrix Model DX-40 slide scanner using the DMetrix digital Retina software (DMetrix, Inc, Tucson, AZ). Digitized images were typically very large data files and could be viewed offline at magnifications ranging from 0.6x to 40x using the DMetrix digital Eyepiece software. They were saved as 24-bit color and 8-bit grayscale TIFF files.

Fluorescence Microscopy

Fluorescence images of Mercury Orange-stained slides were captured with a Leica SP5 confocal microscope using a 10x objective lens with HeNe laser excitation centered at 543 nm and fluorescence emission collected in the 585 ± 20-nm band. A motorized scanning stage was used to acquire contiguous tiles over a field large enough to cover the entire tumor section. An optical zoom factor of 3 was used to reduce intensity mismatches at tile edges. The amplifier gain, magnification, field of view, and digitization matrix size per tile were kept constant across all slides in a given study to permit quantitative comparison of fluorescence intensities between individual tumors. Fused images were saved as 24-bit color and 8-bit grayscale TIFF files.

Data Analysis (Microscopy)

Eight-bit grayscale TIFF files of the tiled fluorescence images were analyzed using a program written in IDL (ITT Visual Information Solutions, Boulder, CO). Images were interactively thresholded to set background-level pixels to zero intensity. One or more regions of interest (ROIs) were then hand-drawn to cover the entire tumor while using the parallel H&E images for visual reference. Mean image intensity (on the 8-bit scale of 0–255) was then computed from all nonzero pixels within the tumor ROIs, and the results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation for each group.

Data Analysis (MRI)

MRI images were analyzed using a program written in IDL to calculate the longitudinal relaxation time (T1) and rate (R1 = 1/T1), as well as the time-varying changes in T1 and R1 (ΔT1 and ΔR1), on a per-pixel basis and also from ROIs drawn around the tumor and the muscle. Precontrast T1 maps and corresponding proton density maps were calculated by pixel wise fitting of the eight precontrast images acquired using eight flip angles to the GRE signal equation. Postcontrast T1 maps were calculated from the precontrast proton density maps and the corresponding postcontrast T1-weighted image using the GRE signal equation. ROIs were drawn around the tumor and muscle using a coregistered T2-weighted scout image as visual guide. Mean ΔT1 and ΔR1 values were computed from the tumor and muscle ROIs, and the results were expressed as mean ± standard deviation for each group.

Statistical Analysis

A two-tailed unpaired Student's t test (Microsoft Excel, Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA) was used to compare ROI means of ΔT1 or ΔR1 between groups imaged using various gadolinium agents at different doses and to compare treatment groups in the drug studies.

Results

MRI Contrast Agent Dose-Response

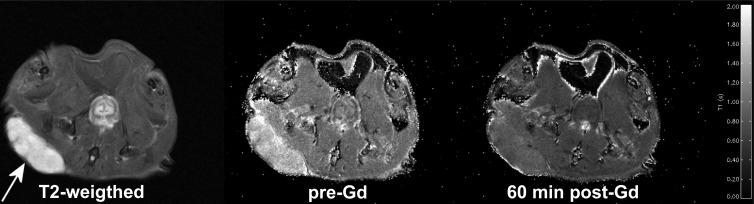

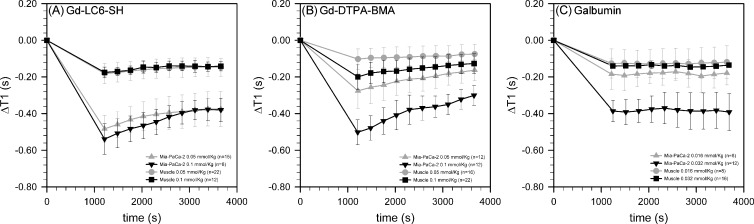

At 7 T and 37°C in PBS, the r1 of Gd-DTPA-BMA was measured to be 3.03/mM/sec, whereas the r1 of Galbumin was measured to be 86.16/mM/sec on a per-BSA basis and 4.86/mM/sec on a per-Gd basis. Under these same conditions, the r1 of Gd-LC6-SH is 3.23/mM/sec, increasing to 4.74/mM/sec when bound to human serum albumin [22]. The time-varying change of tumor and muscle T1 were measured in vivo after injection of the two small-molecule contrast agents at 0.05 mmol/kg and the standard dose of 0.1 mmol/kg. The macromolecule agent Galbumin was injected at 0.016 and 0.032 mmol Gd/kg because significantly higher doses produced unacceptable numbers of animal death soon after injection. Figure 2 depicts an axial T2-weighted MRI image of a SCID mouse bearing a Mia-PaCa-2 tumor xenograft, as well as coregistered T1 maps calculated before and 60 minutes after administration of 0.05 mmol/kg Gd-LC6-SH. The change in T1(ΔT1) relative to precontrast calculated on a pixel-by-pixel basis and averaged in tumor and muscle ROIs is plotted as a function of time in Figure 3. Dynamic data in the first 20 minutes after injection were acquired without signal averaging and were therefore relatively noisy, and have been omitted for visual clarity. As seen in Figure 3A, at 20 minutes (1200 seconds) after injection, Gd-LC6-SH decreased Mia-PaCa-2 tumor T1 by 0.48 seconds at the half-dose and 0.54 seconds at the standard dose, decreasing in both cases to 0.38 seconds by 60 minutes after injection. The corresponding changes in muscle T1were smaller, from 0.18 seconds at 20 minutes after injection to 0.15 seconds at 60 minutes after injection at both doses. As shown in Figure 3B, at the half-dose, Gd-DTPA-BMA decreased Mia-PaCa-2 tumor T1 by 0.28 seconds and muscle T1 by 0.10 seconds at 20 minutes after injection, decreasing to 0.16 seconds in tumor and 0.07 seconds in muscle by 60 minutes after injection. At the standard dose, Gd-DTPA-BMA decreased tumor T1 by 0.50 seconds and muscle T1 by 0.20 seconds at 20 minutes after injection, decreasing to 0.30 seconds in tumor and 0.13 seconds in muscle by 60 minutes after injection. The ΔT1-versus-time plots for both Gd-LC6-SH and Gd-DTPA-BMA show evidence of varying degrees of washout. Whereas Gd-DTPA-BMA demonstrates classic dose-dependent washout kinetics (Figure 3B), the plots for Gd-LC6-SH indicate some degree of retention of the agent in both tumor and muscle such that there is a lack of dose dependence in tumor and muscle at longer times after injection (Figure 3A). The macromolecule Galbumin is not expected to be renally filtered, and the kinetics of this agent were essentially time-invariant between 20 and 60 minutes after injection. Galbumin reduced Mia-PaCa-2 tumor T1 by ∼0.18 seconds and muscle T1 was reduced by ∼0.12 seconds at a gadolinium dose of 0.016 mmol/kg, whereas at a dose of 0.032 mmol/kg, tumor T1 was reduced by ∼0.39 seconds and muscle T1 was reduced by ∼0.14 seconds (Figure 3C).

Figure 2.

T2-weighted axial MR image of a SCID mouse showing a Mia-PaCa-2 tumor xenograft on the right flank (left, arrow), and the corresponding pre-Gd T1 map (center) and T1 map obtained 60 minutes after injection of 0.05 mmol/kg Gd-LC6-SH (right). The T1 map legend runs from 0.0 (black) to 2.0 (white) seconds.

Figure 3.

Decreases in the longitudinal relaxation time T1 of muscle (circles and squares) and Mia-PaCa-2 tumor xenograft (triangles) at various times after injection of (A) Gd-LC6-SH, (B) Gd-DTPA-BMA, and (C) Galbumin. The gadolinium dosesin A and B were 0.05 mmol/kg (gray) or 0.1 mmol/kg (black), and those in C were 0.016 mmol/kg (gray) or 0.032 mmol/kg (black). The number of animals at each condition (n) varied from 8 to 22. Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation at each time point.

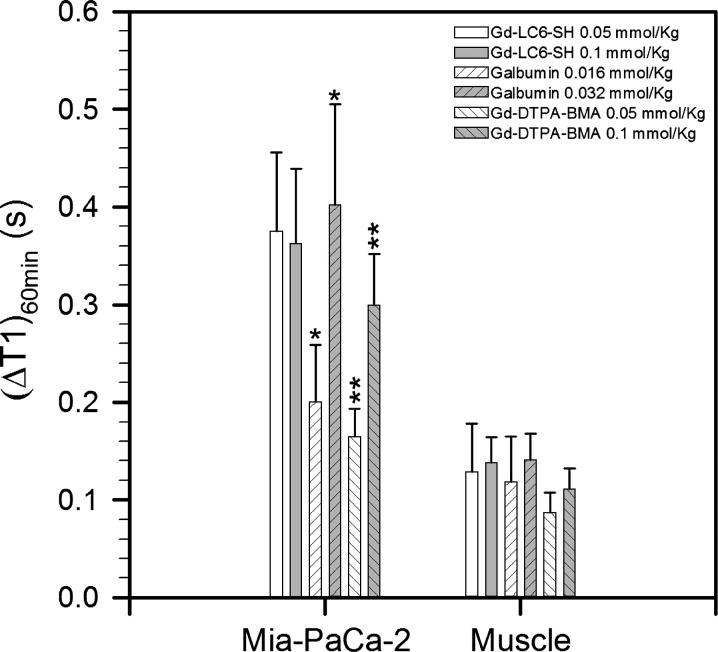

At 60 minutes after injection, the decrease in tumor T1 produced by Galbumin and Gd-DTPA-BMA was dose dependent at the two doses tested (Figure 4; P < .05 for both agents). At 60 minutes after injection, the tumor ΔT1 produced by Galbumin at 0.032 mmol/kg was roughly twice the tumor ΔT1 produced by Galbumin at 0.016 mmol/kg (Figure 4). This is consistent with negligible clearance of the macromolecule from the animal during the course of the experiment. The tumor ΔT1 produced by Gd-DTPA-BMA at 0.1 mmol/kg was also approximately twice that at 0.05 mmol/kg (Figure 4), consistent with renal clearance of this small molecule from the animal with first-order kinetics. The decrease in tumor T1at 60 minutes after injection produced by Gd-LC6-SH at 0.05 mmol/kg was comparable to that produced using twice the dose (Figure 4). This is consistent with binding of a fraction of the injected Gd-LC6-SH to serum albumin (or other nonfiltered targets) in the animal, with continuous renal clearance of the unbound fraction such that by 60 minutes after injection, there is no significant difference in tumor ΔT1 produced by Gd-LC6-SH at the two doses. The decrease in tumor T1at 60 minutes after injection produced by Gd-LC6-SH at the two doses was also comparable to that produced by 0.032 mmol Gd/kg Galbumin but greater than that produced by 0.016 mmol Gd/kg Galbumin (Figure 4). Given the similar per-Gd relaxivities of albumin-bound Gd-LC6-SH and Galbumin, this indicates that the dose of Gd-LC6-SH required to saturate its nonfilterable binding sites in vivo after bolus intravenous administration is less than 0.05 mmol/kg but greater than 0.016 mmol/kg. Muscle ΔT1 at 60 minutes after injection was not dose dependent for any agent, with only a modest shortening of T1 relative to measurement variability (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Summary of the changes (before contrast minus after contrast) in T1 of Mia-PaCa-2 tumor and muscle at 60 minutes after injection of Gd-LC6-SH, Gd-DTPA-BMA, and Galbumin at two different doses of gadolinium. The number of animals at each condition (n) varied from 8to 22. Results are expressed as median ± standard deviation (*,**P < .05).

Microscopy of H&E-Stained Sections

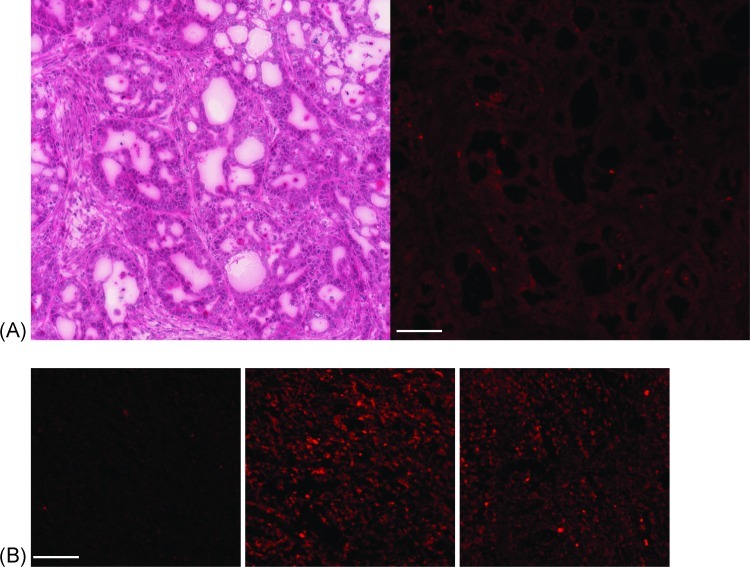

Mia-PaCa-2 pancreatic carcinoma cells in H&E-stained sections appeared diffusely packed and without significant signs of desmoplasia. NCI-N87 gastric carcinoma cells in H&E-stained sections appeared to be organized into glandular structures (Figure 5A). In both tumor types, the H&E-stained sections were used as a visual guide when drawing ROIs on fluorescence images of corresponding Mercury Orange-stained sections.

Figure 5.

(A) H&E-stained light microscopy (left) and Mercury Orange-stained fluorescence microscopy (right) images of adjacent 3-µm sections cut from an NCI-N87 tumor xenograft. (B) Example Mercury Orange-stained fluorescence microscopy images of Mia-PaCa-2 tumor sections treated with 4 mM DTNB in PBS (left), 5 mM DTT in PBS (center), and PBS (right) for 20 minutes at room temperature before staining and fixation. Scale bar, 100 µm in all panels.

Mercury Orange Control Experiments

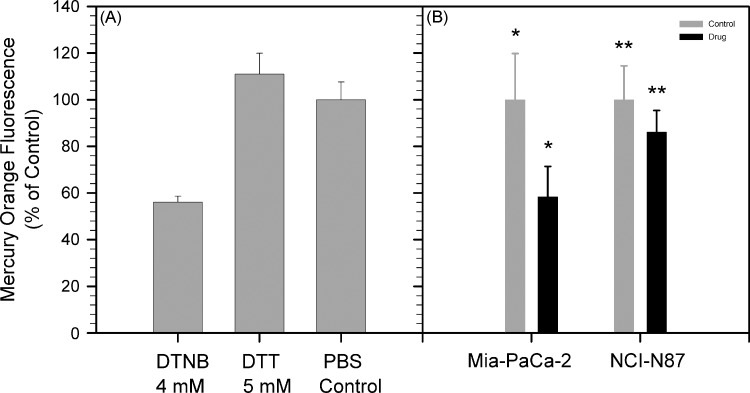

Figure 5B depicts Mercury Orange-stained fluorescence microscopy images of Mia-PaCa-2 tumor sections treated with 4 mM DTNB in PBS, 5 mM DTT in PBS, and PBS (control), for 20 minutes at room temperature before staining and fixation. Mercury Orange binds to thiols, and oxidation of thiols in the tissue sections by the disulfide DTNB produced a significant decrease in Mercury Orange staining relative to the tumor that was treated with only PBS (Figure 6A). Treatment of tumor sections with the reducing agent DTT resulted in a small increase in Mercury Orange staining relative to the PBS control that did not rise to statistical significance (Figure 6A). Two tumor sections were incubated in PBS for 20 minutes at room temperature and then stained with H&E. These sections did not show obvious signs of tissue degradation but did show increased nuclear staining and interstitials welling compared with sections that were fixed and stained without preincubation in PBS.

Figure 6.

(A) Mean ± standard deviation Mercury Orange fluorescence in Mia-PaCa-2 tumor sections (n = 4) treated with DTNB and DTT relative to PBS (control). (B) Mean ± standard deviation Mercury Orange fluorescence in Mia-PaCa-2 tumors after BSO treatment (n = 8; *P < .001) and NCI-N87 tumors after Imexon treatment (n = 8; **P < .05) relative to saline treatment (control).

Mercury Orange Fluorescence Measurements of NPSH

Multidose regimens of BSO injections have previously been noted to provide sustained decreases in tumor GSH, with the nadir occurring 4 hours after an injection [29]. Both MRI and harvest of Mia-PaCa-2 tumors were performed 4 hours after a BSO injection. Tumors were harvested for staining with Mercury Orange on the day after MRI to reduce the likelihood of cross-reactivity with residual Gd-LC6-SH in the tumor. Treatment with BSO decreased Mercury Orange staining intensity by 42% in Mia-PaCa-2 tumors relative to saline-treated controls (P < .001), whereas treatment with Imexon decreased Mercury Orange staining intensity by 14% in NCI-N87 tumors relative to saline-treated control tumors (P <.05; Figure 6B). This response in Mia-PaCa-2 tumors is somewhat less than the 50% to 55% decreases in Mercury Orange fluorescence that have been observed by Vukovic et al. [30] in cervical cancer xenograft tumors after BSO treatment but is comparable to the decrease in GSH measured by Kuppusamy et al. [17] in RIF-1 tumors after BSO treatment.

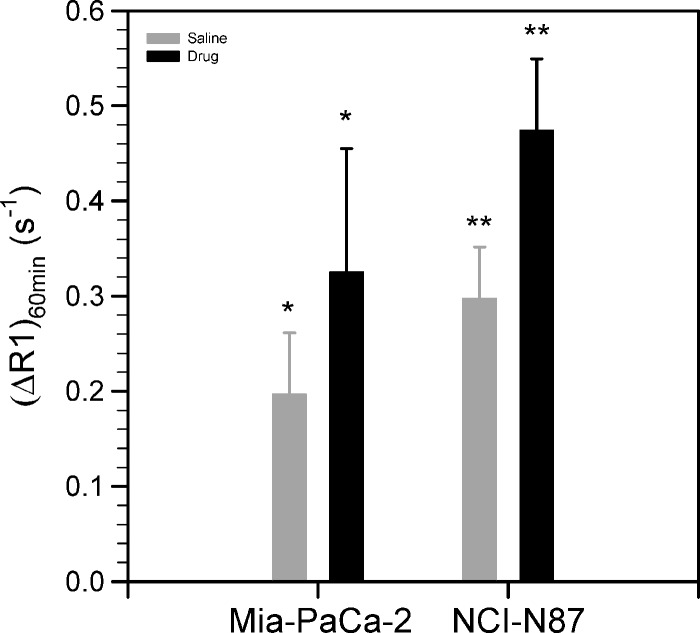

MRI of Tumor Response to BSO and Imexon

The change in longitudinal relaxation rate, ΔR1, in a given pixel can be related to Gd-LC6-SH concentration in that pixel using Equation 1

| (1) |

where T1 is the longitudinal relaxation time at a given time after injection of gadolinium, T10 is the precontrast longitudinal relaxation time, [Gd] is the total concentration of Gd-LC6-SH in the pixel at that given time, and (r1)eff is the weighted average relaxivity of the Gd-LC6-SH between its various forms (free or bound to small molecules versus bound to albumin or other large molecules). Figure 7 depicts the increase in tumor relaxation rate 60 minutes after tail vein injection of 0.05 mmol/kg Gd-LC6-SH (ΔR1_60 min) in mice treated with saline or drug. A significant increase in ΔR1_60 min was measured in Mia-Pa-Ca-2 tumors from BSO-treated mice relative to saline-treated mice (Figure 7; P < .034). A significant increase in ΔR1_60 min was measured in NCI-N87 tumors from Imexon-treated mice relative to saline-treated mice (Figure 7; P < .001).

Figure 7.

Mean ± standard deviation of the change in longitudinal relaxation rates (ΔR1) at 60 minutes after injection of 0.05 mmol/kg Gd-LC6-SH in Mia-PaCa-2 tumors after saline or BSO treatment (n = 8; *P < .034) and NCI-N87 tumors after single-dose treatment with saline or Imexon (n = 8; **P < .001).

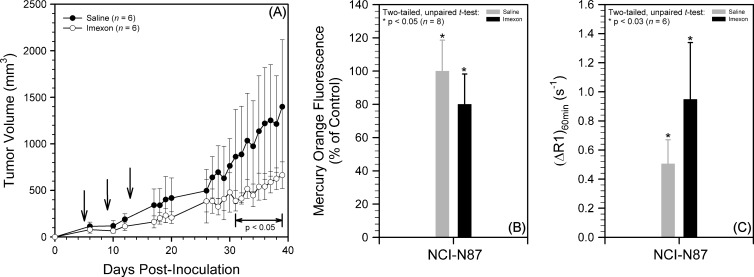

NCI-N87 Tumor Response to Multidose Imexon

We have also investigated the effect of a multidose regimen of Imexon on NCI-N87 tumor xenografts (Figure 8). SCID mice bearing NCI-N87 xenografts were administered saline or Imexon on days 5, 9, and 13 after tumor inoculation. Mean tumor volumes in the Imexon-treated group were smaller than in the saline group, with the difference becoming statistically significant in the period 31 to 39 days after inoculation (Figure 8A); the experiment was terminated at that point because of excessive tumor burdens in some mice in the saline group. In the drug studies reported in Figure 6, tumors were harvested from the same animals that were imaged by MRI, on the day after MRI, after the mice had received an additional dose of saline or drug before tumor harvest. Figure 8 (B and C) reports Mercury Orange and MRI measurements on separate cohorts of mice, with the tumor harvest or MRI occurring 2 hours after saline or Imexon administration on day 13 after inoculation. For the study reported in Figure 8B, four tumors were excluded from each group to yield eight size-matched tumors each in the saline (100 ± 21 mm3) and Imexon (106 ± 33 mm3) treatment groups. Mercury Orange fluorescence was significantly higher in the saline group relative to the Imexon group 2 hours after treatment on day 13 after inoculation (Figure 8B; n = 8, P < .05), indicative of a lower level of reduced thiols in the Imexon group. In the corresponding MRI study, the increase in longitudinal relaxation rates at 60 minutes after injection of 0.05 mmol/kg Gd- LC6-SH (i.e., ΔR1_60 min) in NCI-N87 tumors was significantly higher in Imexon-treated animals compared with saline-treated animals (Figure 8C; n = 6, P < .03).

Figure 8.

Multidose treatment of mice bearing NCI-N87 tumor xenografts with saline or Imexon. (A) Mean ± standard deviation tumor volumes versus days after inoculation (n = 6; P < .05 in period indicated, arrows indicate treatment). (B) Mean ± standard deviation Mercury Orange fluorescence after Imexon treatment relative to saline control on day 13 after inoculation (n = 8; *P < .05). (C) Mean ± standard deviation of the change in longitudinal relaxation rates (ΔR1) at 60 minutes after injection of 0.05 mmol/kg Gd-LC6-SH in NCI-N87 tumors after treatment with saline or Imexon on day 13 after inoculation (n = 6; *P < .03).

Discussion

Previous results with Gd-LC6-SH [22,23] suggest that it binds to the Cys34 residue in human serum albumin, a residue that is conserved in mammalian albumins. The longitudinal relaxivity (r1) of Gd-LC6-SH is 47% higher when it is bound to albumin, compared with the r1 of the molecule by itself or when it is bound to another small molecule. In more reducing microenvironments, competition for binding to the Cys34 by endogenous small-molecule thiols is likely to decrease the bound fraction of Gd-LC6-SH. Thus, we hypothesized that a higher relaxation rate would be expected in an oxidizing tumor microenvironment relative to a reducing tumor microenvironment. A confounding factor is that the change in tumor relaxation rate could also be a function of the injected dose of Gd. We have exploited the prolonged retention of albumin-bound Gd-LC6-SH in the mouse to identify a dose and time after injection at which the change in tumor R1 is insensitive to injected dose. Albumin-bound Gd-LC6-SH is protected from renal filtration, and we hypothesized that, at sufficiently long times after injection (e.g., 60 min), bulk Gd-LC6-SH not bound to a macromolecular target has been cleared and a pseudo steady-state is established between bound and free Gd-LC6-SH in tumor. The results in Figures 3 and 4 are consistent with the saturation of Cys34 binding sites for Gd-LC6-SH on serum albumin when a dose of 0.05 mmol/kg is used, such that by 60 minutes after injection, there is still significant shortening of tumor T1 but not significantly less so than when a dose of 0.1 mmol/kg is used. We have explored the utility of ΔR1_60 min as a biomarker of tumor redox status in Mia-PaCa-2 tumor xenografts after treatment with the glutathione synthesis inhibitor BSO and in NCI-N87 tumors after treatment with the thiol-oxidizing drug Imexon. An advantage of being able to wait 60 minutes after injection is that it allows more time for tissues to recover from any potential perturbation of redox caused by injection of the tracer itself. Systemic perturbations are further minimized by using half the standard dose of gadolinium in these experiments.

From Equation 1, in the dose-insensitive regime, tumor ΔR1_60 min can be related to (r1)eff, which in turn depends on the ratio of free versus bound Gd-LC6-SH in the tumor. We see a significant increase in ΔR1_60 min (Figure 7) and decrease in Mercury Orange staining (Figure 6B) of Mia-PaCa-2 tumors with BSO treatment relative to control tumors. This is consistent with an oxidizing effect of BSO treatment on Mia-PaCa-2 tumors, leading to increased binding of Gd-LC6-SH to albumin in the tumor with a consequent increase in ΔR1_60 min after treatment. Studies of the chemical reactivity of Imexon with the sulfur atom of small-molecule thiols showed that binding could occur by two routes: a classic opening of the aziridine ring of Imexon to form a drug-GSH conjugate or opening of the iminopyrrolidone ring of Imexon to yield a thiazoline conjugate with cysteine [31]. In human 8226 multiple myeloma cells, Imexon induced a concentration-dependent decrease in both oxidized and reduced glutathione levels that was correlated with the induction of apoptosis [5]. Furthermore, in an initial phase 1 clinical trial of Imexon in cancer patients, Imexon decreased the plasma levels of cystine in proportion to the area under the curve of drug achieved in the blood of the study participants. This finding is consistent with a depletion of reduced sulfhydryls in cells after Imexon therapy, leading to depletion of plasma cystine, which comprises the primary cysteine storage form used to replenish intracellular GSH [32]. The plasma half-life of Imexon in mice is 12 to 15 minutes after intraperitoneal injection, whereas the nadir in tissue GSH levels occurs 2 to 4 hours after administration [33]. The ΔR1_60 min of NCI-N87 tumors was significantly larger in Imexon-treated mice than in saline-treated mice (Figures 7 and 8C). This is consistent with an oxidizing effect of Imexon treatment on NCI-N87 tumors, leading to increased binding of Gd-LC6-SH to albumin in the tumor and, consequently, an increase in ΔR1_60 min after treatment. These MRI results are supported by assays of tissue thiol levels using the histologic stain Mercury Orange (Figures 6B and 8B). An important difference between the MRI and Mercury Orange measurements is that, whereas the MRI contrast agent Gd-LC6-SH would be expected to respond primarily to extracellular thiols (the agent is not expected to cross the cell membrane), the Mercury Orange would be expected to stain for both intracellular and extracellular thiols with the former being the dominant pool [14]. However, it is reasonable for there to be metabolic connectivity between the intracellular and extracellular pools of thiols in a tumor, especially given the known control of γ-GT and MRP expression by the NRF2 transcription factor [1]. Although gadolinium complexes generally do not cross the cell membrane by themselves, it should be noted that SPARC secretion by stromal fibroblasts is a feature of many tumors [34]. It has been suggested that high levels of SPARC can lead to accumulation of albumin in tumors [35]; this could conceivably lead to increased tumor retention of albumin-bound Gd-LC6-SH. We have not investigated either tumor model for potential changes in albumin uptake after drug treatment.

GSH and cysteine can chemically reduce and repair DNA radicals produced by ionizing radiation, potentially serving as a mechanism of radioresistance in tumors. Research efforts to identify agents that will augment the therapeutic index of radiation therapy have shifted toward more targeted biologic agents that either modulate redox reactions within tumor cells or are activated under certain redox conditions [36]. Moreno-Merlo et al. [37] have demonstrated that NPSH levels are ∼50% greater in hypoxic regions of human cervical cancer xenografts, relative to better oxygenated tumor tissue, and that hypoxic regions that are proximal to blood vessels have greater levels of NPSH than nor moxic regions or distal hypoxic regions [38]. But in a limited study, tumor NPSH levels were not predictive of the outcome in patients with locally advanced cervical carcinomas who were treated with radiation therapy [39]. Difficulties in relating tumor NPSH levels to outcome in patients can be appreciated from the finding that GSH and N-acetylcysteine inhibit the activation and function of MMP-9, a matrix metalloproteinase implicated in the malignant progression of precancerous lesions, by preserving the cysteine sulfur blockage of the active site in the propeptide [40]. The physiological small-molecule thiols cysteine, homocysteine, and GSH have been reported to cause inactivation of transforming growth factor β, which functions as a tumor suppressor in early stages of carcinogenesis but can induce epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition of cells in late-stage tumors and promote tumor growth and metastasis [41]. Thus, high levels of tumor NPSH may influence both cancer progression and tumor response to therapies but toward opposing clinical outcomes. This highlights the need for noninvasive techniques for measuring tumor redox in vivo. We have presented a paradigm wherein thiol-containing complexes of gadolinium such as Gd-LC6-SH can serve as redox-sensitive MRI contrast agents. One can envision a role for redox-sensitive MRI in personalized cancer therapy, from prospectively identifying a patient subset that might be more (or less) susceptible to redox-dependent drug therapy, to monitoring tumor response to novel redox-active therapies by imaging. Further optimization of these gadolinium agents must focus on increasing the difference in r1 between free and albumin-bound gadolinium, as well as fine-tuning the sensitivity of the complexes to the presence of competing small-molecule thiols.

Footnotes

This work was funded through the following grants from the National Institutes of Health: R01-CA118359, P01-CA017094, and P30-CA023074.

References

- 1.Hayes JD, McMahon M. NRF2 and KEAP1 mutations: permanent activation of an adaptive response in cancer. Trends Biochem Sci. 2009;34:176–188. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson ME. Glutathione: an overview of biosynthesis and modulation. Chem Biol Interact. 1998;111–112:1–14. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(97)00146-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen X, Carystinos GD, Batist G. Potential for selective modulation of glutathione in cancer chemotherapy. Chem Biol Interact. 1998;111–112:263–275. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(97)00166-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pompella A, De Tata V, Paolicchi A, Zunino F. Expression of γ-glutamyltransferase in cancer cells and its significance in drug resistance. Biochem Pharmacol. 2006;71:231–238. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dvorakova K, Payne CM, Tome ME, Briehl MM, McClure T, Dorr RT. Induction of oxidative stress and apoptosis in myeloma cells by the aziridine-containing agent Imexon. Biochem Pharmacol. 2000;60:749–758. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00380-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lin X, Zhang F, Bradbury CM, Kaushal A, Li L, Spitz DR, Aft RL, Gius D. 2-Deoxy-d-glucose-induced cytotoxicity and radiosensitization in tumor cells is mediated via disruptions in thiol metabolism. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3413–3417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coleman MC, Asbury CR, Daniels D, Du J, Aykin-Burns N, Smith BJ, Li L, Spitz DR, Cullen JJ. 2-Deoxy-d-glucose causes cytotoxicity, oxidative stress, and radiosensitization in pancreatic cancer. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;44:322–331. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cho H, Koto M, Riesterer O, Molkentine DP, Giri U, Milas L, Story MD, Ha CS, Raju U. Imexon augments sensitivity of human lymphoma cells to ionizing radiation: in vitro experimental study. Anticancer Res. 2009;29:4409–4416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tuttle S, Horan A, Koch CJ, Held K, Manevich Y, Biaglow J. Radiation-sensit ive tyrosine phosphorylation of cellular proteins: sensitive to changes in GSH content induced by pretreatment with N-acetyl-l-cysteine or l-buthionine-S,R-sulfoximine. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1998;42:833–838. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(98)00331-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Richardson ME, Siemann DW. Tumor cell heterogeneity: impact on mechanisms of therapeutic drug resistance. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;39:789–795. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(97)00469-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Renschler MF. The emerging role of reactive oxygen species in cancer therapy. Eur J Can. 2004;40:1934–1940. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2004.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu RM, Gaston Pravia KA. Oxidative stress and glutathione in TGF-β-mediated fibrogenesis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;48:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2009.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ballatori N, Krance SM, Marchan R, Hammond CL. Plasma membrane glutathione transporters and their roles in cell physiology and pathophysiology. Mol Aspects Med. 2009;30:13–28. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jones DP, Carlson JL, Mody VC, Cai J, Lynn MJ, Sternberg P. Redox state of glutathione in human plasma. Free Radic Biol Med. 2000;28:625–635. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00275-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Opstad KS, Provencher SW, Bell BA, Griffiths JR, Howe FA. Detection of elevated glutathione in meningiomas by quantitative in vivo 1H MRS. Magn Reson Med. 2003;49:632–637. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thelwall PE, Yemin AY, Gillian TL, Simpson NE, Kasibhatla MS, Rabbani ZN, Macdonald JM, Blackband SJ, Gamcsik MP. Noninvasive in vivo detectio n of glutathio ne metabolism in tumors. Cancer Res. 2005;65:10149–10153. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuppusamy P, Li H, Ilangovan G, Cardounel AJ, Zweier JL, Yamada K, Krishna MC, Mitchell JB. Noninvasive imaging of tumor redox status and its modification by tissue glutathione levels. Cancer Res. 2002;62:307–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hyodo F, Matsumoto K, Matsumoto A, Mitchell JB, Krishna MC. Probing the intracellular redox status of tumors with magnetic resonance imaging and redox-sensitive contrast agents. Cancer Res. 2006;66:9921–9928. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gallez B, Bacic G, Goda F, Jiang J, O'Hara JA, Dunn JF, Swartz HM. Use of nitroxides for assessing perfusion, oxygenation, and viability of tissues: in vivo EPR and MRI studies. Magn Reson Med. 1996;35:97–106. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910350113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davis RM, Matsumoto S, Bernardo M, Sowers A, Matsumoto K-I, Krishna MC, Mitchell JB. Magnetic resonance imaging of organic contrast agents in mice: capturing the whole-body redox landscape. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;50:459–468. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tu C, Osborne EA, Louie AY. Synthesis and characterization of a redox- and light-sensitive MRI contrast agent. Tetrahedron. 2009;65:1241–1246. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2008.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raghunand N, Guntle GP, Gokhale V, Nichol G, Mash EA, Jagadish B. Design, synthesis, and evaluation of 1,4,7,10-tetraazacyclododecane-1,4,7-triacetic acid-derived, redox-sensitive contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging. J Med Chem. 2010;53:6747–6757. doi: 10.1021/jm100592u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Raghunand N, Jagadish B, Trouard TP, Galons JP, Gillies RJ, Mash EA. Redox-sensitive contrast agents for MRI based on reversible binding of thiols to serum albumin. Magn Reson Med. 2006;55:1272–1280. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bennett HS. The demonstration of thiol groups in certain tissues by means of a new colored sulfhydryl reagent. Anat Rec. 1951;110:231–247. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091100208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asghar K, Reddy BG, Krishna G. Histochemical localization of glutathione in tissues. J Histochem Cytochem. 1975;3:774–779. doi: 10.1177/23.10.53246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chieco P, Boor PJ. Use of low temperatures for glutathione histochemical stain. J Histochem Cytochem. 1983;31:975–976. doi: 10.1177/31.7.6189887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Larrauri A, Lopez P, Gomez-Lechon M-J, Castell JV. A cytochemical stain for glutathione in rat hepatocytes cultured on plastic. J Histochem Cytochem. 1987;35:271–274. doi: 10.1177/35.2.2432118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vukovic V, Nicklee T, Hedley DW. Microregional heterogeneity of non-protein thiols in cervical carcinomas assessed by combined use of HPLC and fluorescence image analysis. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:1826–1832. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Minchinton AI, Rojas A, Smith A, Soranson JA, Shrieve DC, Jones NR, Bremner JC. Glutathione depletion in tissues after administration of buthionine sulphoximine. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1984;10:1261–1264. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(84)90329-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Vukovic V, Nicklee T, Hedley DW. Differential effects of buthionine sulphoximine in hypoxic and non-hypoxic regions of human cervical carcinoma xenografts. Radiother Oncol. 2001;60:69–73. doi: 10.1016/s0167-8140(01)00331-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iyengar BS, Dorr RT, Remers WA. Chemical basis for the biological activity of Imexon and related cyanoaziridines. J Med Chem. 2004;47:218–223. doi: 10.1021/jm030225v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dragovich T, Gordon M, Mendelson D, Wong L, Modiano M, Chow HHS, Samulitis B, O'Day S, Grenier K, Hersh E, et al. Phase 1 trial of Imexon in patients with advanced malignancy. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1779–1784. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.9672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pourpak A, Meyers RO, Samulitis BK, Chow HHS, Kepler CY, Raymond MA, Hersh E, Dorr RT. Preclinical antitumoractivity, pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of Imexon in mice. Anti-Cancer Drugs. 2006;17:1179–1184. doi: 10.1097/01.cad.0000236305.43209.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mantoni TS, Schendel RRE, Rodel F, Niedobitek G, Al-Assar O, Masamune A, Brunner TB. Stromal SPARC expression and patient survival after chemoradiation for non-resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Cancer Biol Ther. 2008;7:1806–1815. doi: 10.4161/cbt.7.11.6846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Desai N, Trieu V, Damascelli B, Soon-Shiong P. SPARC expression correlates with tumor response to albumin-bound paclitaxel in head and neck cancer patients. Translational Oncol. 2009;2:59–64. doi: 10.1593/tlo.09109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosenberg A, Knox S. Radiation sensitization with redox modulators: a promising approach. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;64:343–354. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moreno-Merlo F, Nicklee T, Hedley DW. Association between tissue hypoxia and elevated non-protein sulphydryl concentrations in human cervical carcinoma xenografts. Br J Can. 1999;81:989–993. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6690797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vukovic V, Nicklee T, Hedley DW. Multiparameter fluorescence mapping of nonprotein sulfhydryl status in relation to blood vessels and hypoxia in cervical carcinoma xenografts. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;52:837–843. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(01)02716-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hedley DW, Nicklee T, Moreno-Merlo F, Pintilie M, Fyles A, Milosevic M, Hill RP. Relations between non-protein sulfhydryl levels in the nucleus and cytoplasm, tumor oxygenation, and clinical outcome of patients with uterine cervical carcinoma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;61:137–144. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2004.02.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pei P, Horan MP, Hille R, Hemann CF, Schwendeman SP, Mallery SR. Reduced nonprotein thiols inhibit activation and function of MMP-9: implications for chemoprevention. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;41:1315–1324. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Blakytny R, Erkell LJ, Brunner G. Inactivation of active and latent transforming growth factor beta by free thiols: potential redox regulation of biological action. Intl J Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;38:1363–1373. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2006.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]