Abstract

Commercial vaccines against Porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2) are widely used on swine farms. Marked body weight variation at marketing age is a problem on conventional pig farms using all-in/all-out barn management. The aim of this study was to investigate whether PCV2 infection could be a factor influencing body weight variation. Seven conventional farms that routinely used PCV2 vaccination were selected, and 60 serum samples from light and heavy pigs at each site were tested for PCV2 antibody titers and viremia. At 3 farms the mean antibody titer, proportion of viremic pigs, and virus load differed significantly between the light and heavy groups. These preliminary results suggest that PCV2 infection may be a factor contributing to weight variation in vaccinated market-age hogs.

Résumé

Les vaccins commerciaux contre le circovirus porcin de type 2 (PCV2) sont largement utilisés sur les fermes porcines. Les variations marquées du poids corporel à l’âge de la mise en marché sont un problème sur les fermes porcines conventionnelles utilisant une gestion de type tout plein/tout vide. L’objectif de la présente étude était de vérifier si l’infection par PCV2 pouvait être un facteur influençant les variations de poids corporel. Sept fermes conventionnelles utilisant de routine la vaccination contre PCV2 furent sélectionnées; 60 échantillons de sérum provenant de porcs légers et de porcs lourds à chaque site ont été éprouvés pour déterminer les titres d’anticorps anti-PCV2 et la virémie. Pour 3 fermes, le titre moyen d’anticorps, la proportion de porcs virémiques et la charge virale différaient de manière significative entre les groupes léger et lourd. Ces résultats préliminaires suggèrent que l’infection par PCV2 pourrait être un facteur contribuant à la variation de poids chez les porcs vaccinés de poids de marché.

(Traduit par Docteur Serge Messier)

Porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2) is regarded as an essential causative agent of PCV-associated diseases (PCVAD), a global epizootic that has caused significant economic losses to swine industries (1,2). Although the pathogenesis of PCVAD is complex, recent observations that the prevalence of the PCV2b genotype has dramatically increased on farms with clinical PCVAD may help in our understanding (3–5).

Several PCV2 vaccines have been successfully used to prevent PCV2 infections. The efficacy of vaccination was demonstrated in significantly reduced mortality rates among growing pigs and improved growth performance under field conditions (6,7). However, light-weight late-finishing pigs have continued to be observed on the farms routinely vaccinating against PCV2. Therefore, it is hypothesized that a light weight at market age could result from PCV2 viremia in vaccinated pigs. This preliminary study was designed to compare PCV2 viremia and antibody status in the pigs that were lightest and heaviest at market age on conventional farms that vaccinated routinely against PCV2.

Seven finishing farms in Minnesota with average inventories of 2400 to 5200 pigs were selected for the study (Table I). All the pigs had been vaccinated with a commercial PCV2 vaccine around the time of weaning, the age at vaccination ranging up to 7 d within a room. None of the farms had clinical problems related to PCVAD according to herd veterinarian assessments. At less than 2 wk before first marketing, 30 of the lightest and 30 of the heaviest pigs were selected in 1 finishing barn (containing 350 to 500 finishing pigs) on each farm. Blood samples were collected from the 60 pigs on each farm, and the serum was stored at −70°C until laboratory analysis. Indirect fluorescent antibody (IFA) testing, differential nested polymerase chain reaction assay for PCV2 subtypes 2a and 2b, and PCV2b-specific quantitative real-time PCR assay for virus load (number of genome copies) were conducted as previously described (8,9).

Table I.

History of vaccination of finishing pigs against Porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2) and blood sample collection on 7 farms

| Farm | Number of pigs | Vaccinea and age at vaccination (wk) | Age at sampling (wk) | Mean body weight of group (kg)

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Light | Heavy | ||||

| A | 440 | BI (6) | 21 | 73 | 109 |

| B | 420 | IV (3 & 5) | 20 | 73 | 109 |

| C | 450 | IV (3 & 5) | 22–23 | 71 | 105 |

| D | 480 | IV (3 & 5) | 23 | 75 | 109 |

| E | 500 | BI (4) | 22 | 73 | 118 |

| F | 380 | BI (3) | 22 | 95 | 122 |

| G | 350 | IV (3 & 5) | 23 | 80 | 120 |

BI — Ingelvac CircoFLEX, Boehringer Ingelheim Vetmedica, St. Joseph, Missouri, USA; 1 dose of 1.0 mL. IV — Circumvent PCV, Intervet/Schering–Plough Animal Health, Summit, New Jersey, USA; 2 doses of 2.0 mL.

Statistical analysis was based on the individual pig. Assumptions of normality and homoscedasticity of the transformed data were tested with the Shapiro–Wilks test and the Levene test, respectively. The IFA log2 titer and the virus load were examined for differences between the groups by 1-way analysis of variance and Student’s t-test as a parametric test. The proportions of viremic pigs were analyzed by the nonparametric Wilcoxon and Mann–Whitney tests. Statistical analyses of the parametric and nonparametric data were performed with the use of SPSS software, student version 15.0 (SPSS, Chicago, Illinois, USA). A P-value of less than 0.05 was used to infer statistical significance.

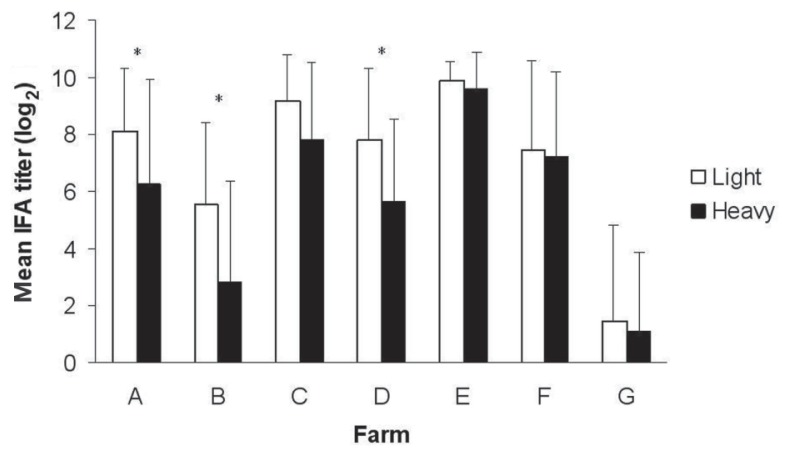

The mean IFA titers in the 2 weight groups of market-age pigs on the 7 farms are illustrated in Figure 1. Overall, the titers of the light pigs were higher than those of the heavy pigs, and at 3 of the 7 farms significantly so. As Table II shows, there was no statistically significant difference in the proportion of pigs with PCV2a viremia between the light and heavy groups on any farm. The prevalence of coinfection with PCV2a and 2b was low in both weight groups, and the rates were not significantly different. In contrast, the proportion of pigs with PCV2b viremia was significantly higher in the light group than in the heavy group on 3 of the 7 farms. Overall, the virus load, as indicated by the quantity of PCV2b genomic DNA (log10), was higher in the light pigs than in the heavy pigs (Table III), and on 3 of the 7 farms significantly so (P < 0.05).

Figure 1.

Comparison of the mean log2 titers of immunofluorescent antibody against Porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2) in serum from 30 light and 30 heavy pigs of market age selected on each of 7 finishing farms. The error bars indicate standard deviation and the asterisks a significant difference between the groups (P < 0.05).

Table II.

Proportions of pigs with each type of PCV viremia according to body weight

| Virus genotype; weight group; proportion (and percent) of tested pigs with viremia

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PCV2a

|

PCV2b

|

|||||

| Farm | Light | Heavy | P-value | Light | Heavy | P-valuea |

| A | 3/30 (10) | 5/30 (17) | 0.157 | 8/30 (27) | 2/30 (7) | 0.097 |

| B | 1/30 (3) | 1/30 (3) | 1.0 | 10/30 (33) | 7/30 (23) | 0.083 |

| C | 3/30 (10) | 4/30 (13) | 0.317 | 28/30 (93) | 28/30 (93) | 1.0 |

| D | 3/28 (11) | 0/28 (0) | 0.083 | 27/28 (96) | 16/28 (57) | 0.001 |

| E | 2/29 (7) | 0/29 (0) | 0.157 | 28/29 (97) | 3/29 (10) | 0.001 |

| F | 2/28 (7) | 2/28 (7) | 1.0 | 16/28 (57) | 12/28 (43) | 0.046 |

| G | 0/30 (0) | 0/30 (0) | 1.0 | 6/30 (20) | 4/30 (13) | 0.157 |

| Total | 14/205 (7) | 12/205 (6) | 0.157 | 123/205 (60) | 72/205 (35) | 0.001 |

Values in bold face indicate a significant difference between the weight groups.

Table III.

Mean number of PCV2b genomic copies (log10) per milliliter of serum of light and heavy pigs with PCV2b viremia

| Weight group; mean number of genomic copies/mL (± standard error)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Farm | Light | Heavy | P-value |

| A | 2.70 ± 1.46 | 2.53 ± 1.56 | 0.363 |

| B | 4.28 ± 2.32 | 2.94 ± 2.10 | 0.042 |

| C | 6.05 ± 2.11 | 5.23 ± 2.13 | 0.117 |

| D | 5.04 ± 0.92 | 3.65 ± 1.56 | 0.0003 |

| E | 5.64 ± 0.75 | 4.12 ± 1.72 | 0.0004 |

| F | 2.99 ± 2.09 | 2.83 ± 2.36 | 0.446 |

| G | 1.28 ± 1.17 | 1.15 ± 1.03 | 0.473 |

| Total | 4.02 ± 2.29 | 3.37 ± 2.25 | 0.012 |

In previous studies, the administration of commercial PCV2 vaccines significantly increased weight gain, and the vaccinated pigs were heavier on average at market age than the unvaccinated pigs (9,10). However, marked variation of body weight among pigs of market age has been observed by swine practitioners and producers despite the routine use of PCV2 vaccine. Moreover, PCV2 viremia was continuously detected in vaccinated pigs until market age (6,10).

In this study, the pigs on all 7 farms had been routinely vaccinated with 1 of the PCV2 commercial vaccines and had no evidence of a clinical wasting syndrome or unusual morbidity. However, a number of underweight pigs were observed in the same barns at finishing age, and the weight difference was more than 27 kg. Some variation in weight gain is an inevitable aspect of swine production. Increased variation can be associated with nutritional, environmental, genetic, or disease factors, including vaccine failure. Opriessnig et al (11) addressed the issue that vaccine failure is particularly common among pigs vaccinated early, because the pigs could be infected by PCV2 during the middle and late finishing phases. In our previous studies, neutralizing antibody and IFA levels in conventionally reared pigs vaccinated at weaning age almost decayed around 15 wk of age, after which the level of PCV2 viremia increased until marketing (9). The value of commercial PCV2 vaccines is largely unquestioned by veterinarians, but some uncertainty remains about optimal vaccination protocols in commercial herds.

Most commercial PCV2 vaccines are designed to be injected at weaning age because PCV2 replication and PCV2-associated lesions are minimal in pigs vaccinated 2 to 4 wk before exposure to PCV2 (12). Nevertheless, finishing pigs are still susceptible to PCV2 infection, and the economic impact of infection in older pigs is likely to be greater than that in younger animals (12,13). Although some studies have described the status of PCV2 infection in finishing pigs, there are relatively few reports of PCV2 pathogenesis or vaccine efficacy in finishing pigs.

The present study showed differences in PCV2b viremia and antibody levels between light and heavy pigs of market age. Therefore, market weight may be associated with PCV2 infection even in vaccinated and clinically asymptomatic herds. We suggest that farm managers and veterinarians consider modifying vaccination protocols in herds with unacceptably high variability in body weight at market age. Since this observational study was performed as a preliminary investigation, a more controlled experimental study should be conducted to confirm these potential effects of PCV2 infection in vaccinated pigs. This information will be important for optimizing PCV2 vaccination protocols in swine herds.

Acknowledgment

This study was funded by a grant from MJ Biologics, Mankato, Minnesota, USA.

References

- 1.Allan GM, Ellis JA. Porcine circoviruses: A review. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2000;12:3–14. doi: 10.1177/104063870001200102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Segalés J, Allan GM, Domingo M. Porcine circovirus diseases. Anim Health Res Rev. 2005;6:119–142. doi: 10.1079/ahr2005106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dupont K, Nielsen EO, Baekbo P, Larsen LE. Genomic analysis of PCV2 isolates from Danish archives and a current PMWS case–control study supports a shift in genotypes with time. Vet Microbiol. 2008;128:56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2007.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olvera A, Cortey M, Segalés J. Molecular evolution of porcine circovirus type 2 genomes: Phylogeny and clonality. Virology. 2007;357:175–185. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2006.07.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grau-Roma L, Crisci E, Sibila M, et al. A proposal on porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2) genotype definition and their relation with postweaning multisystemic wasting syndrome (PMWS) occurrence. Vet Microbiol. 2008;128:23–35. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2007.09.007. Epub 2007 Sep 19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kixmoller M, Ritzmann M, Eddicks M, Saalmuller A, Elbers K, Fachinger V. Reduction of PMWS-associated clinical signs and co-infections by vaccination against PCV2. Vaccine. 2008;26:3443–3451. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kristensen CS, Baadsgaard NP, Toft N. A meta-analysis comparing the effect of PCV2 vaccines on average daily weight gain and mortality rate in pigs from weaning to slaughter. Prev Vet Med. 2011;98:250–258. doi: 10.1016/j.prevetmed.2010.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lyoo KS, Kim HB, Joo HS. Evaluation of a nested polymerase chain reaction assay to differentiate between two genotypes of Porcine circovirus-2. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2008;20:283–288. doi: 10.1177/104063870802000304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lyoo K, Joo H, Caldwell B, Kim H, Davies PR, Torrison J. Comparative efficacy of three commercial PCV2 vaccines in conventionally reared pigs. Vet J. 2011;189:58–62. doi: 10.1016/j.tvjl.2010.06.015. Epub 2010 Aug 5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horlen KP, Dritz SS, Nietfeld JC, et al. A field evaluation of mortality rate and growth performance in pigs vaccinated against porcine circovirus type 2. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2008;232:906–912. doi: 10.2460/javma.232.6.906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Opriessnig T, Patterson AR, Madson DM, Pal N, Halbur PG. Comparison of efficacy of commercial one dose and two dose PCV2 vaccines using a mixed PRRSV–PCV2–SIV clinical infection model 2–3-months post vaccination. Vaccine. 2009;27:1002–1007. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.11.105. Epub 2008 Dec 25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Opriessnig T, Meng XJ, Halbur PG. Porcine circovirus type 2 associated disease: Update on current terminology, clinical manifestations, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and intervention strategies. J Vet Diagn Invest. 2007;19:591–615. doi: 10.1177/104063870701900601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brunborg IM, Fossum C, Lium B, et al. Dynamics of serum antibodies to and load of porcine circovirus type 2 (PCV2) in pigs in three finishing herds, affected or not by postweaning multisystemic wasting syndrome [abstract] Acta Vet Scand. 2010;52:22. doi: 10.1186/1751-0147-52-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]