Abstract

The Drosophila Suppressor of Hairy-wing [Su(Hw)] protein is a globally expressed, multi-zinc finger (ZnF) DNA-binding protein. Su(Hw) forms a classic insulator when bound to the gypsy retrotransposon and is essential for female germline development. These functions are genetically separable, as exemplified by Su(Hw)f that carries a defective ZnF10, causing a loss of insulator but not germline function. Here, we completed the first genome-wide analysis of Su(Hw)-binding sites (SBSs) in the ovary, showing that tissue-specific binding is not responsible for the restricted developmental requirements for Su(Hw). Mapping of ovary Su(Hw)f SBSs revealed that female fertility requires binding to only one third of the wild-type sites. We demonstrate that Su(Hw)f retention correlates with binding site affinity and partnership with Modifier of (mdg4) 67.2 protein. Finally, we identify clusters of co-regulated ovary genes flanked by Su(Hw)f bound sites and show that loss of Su(Hw) has limited effects on transcription of these genes. These data imply that the fertility function of Su(Hw) may not depend upon the demarcation of transcriptional domains. Our studies establish a framework for understanding the germline Su(Hw) function and provide insights into how chromatin occupancy is achieved by multi-ZnF proteins, the most common transcription factor class in metazoans.

INTRODUCTION

Transcription factors execute complex gene expression programs important for the diversity of cellular phenotypes. These processes depend upon the proper action of enhancers and silencers that modulate transcriptional output of a promoter. Enhancers and silencers act over long distances and display limited promoter specificity, requiring additional mechanisms to ensure promoter selectivity. One class of elements that constrain enhancer and silencer action is insulators, regulators that are defined by two properties (1–3). First, insulators block enhancer–promoter communication in a position-dependent manner, such that an insulator prevents enhancer-activated transcription only when located between the enhancer and promoter. Second, insulators act as barriers that disrupt the spread of repressive chromatin. Insulator function depends upon the assembly of protein complexes, initiated by a DNA-binding protein. Recognition motifs for insulator binding proteins represent one of the most conserved non-coding DNA elements in metazoan genomes (4,5), indicating that insulator proteins have a critical role in transcriptional regulation.

The Drosophila Suppressor of Hairy-wing [Su(Hw)] protein was one of the first insulator proteins identified (6,7). This 12 zinc finger (ZnF) protein plays a key role in establishing the insulator within the 5′-untranslated region (UTR) of the gypsy retrovirus (8–11). The gypsy insulator is comprised of 12 tightly clustered Su(Hw)-binding sites (SBSs). The architecture of SBSs within the gypsy insulator plays an important role in its function, as deletion of binding sites or insertions into the insulator compromise enhancer blocking (12–14). Enhancer blocking by the gypsy insulator requires Su(Hw)-dependent recruitment of two Broad-complex, Tramtrack and Bric-a-brac (BTB) domain cofactors, Modifier of (mdg4) 67.2 (Mod67.2) and Centrosomal Protein of 190 kDa (CP190) (15,16), whereas formation of a barrier against the spread of repressive chromatin requires recruitment of the Enhancer of yellow 2 (ENY2) protein (17). The gypsy insulator is portable, with evidence that placing this insulator into transgenes confers protection from chromosomal position effects throughout the Drosophila genome (18,19), as well as in other organisms (20). Based on these observations, the Su(Hw)-binding region of gypsy has become a paradigmatic insulator and Su(Hw) a classical insulator protein.

A large number of su(Hw) mutants have been identified based on reversal of gypsy-induced mutations (7,21,22). In addition to suppressing gypsy-induced phenotypes, most su(Hw) mutants show defects in female germline development, wherein oocytes are lost due to mid-oogenesis apoptosis (22). Among the su(Hw) mutants identified, two alleles carry missense mutations that disrupt a single ZnF within the multi-ZnF domain. The su(Hw)E8 mutation encodes a full-length Su(Hw) protein with a defective ZnF7, resulting in suppression of gypsy insulator activity and female sterility. These defects correlate with a loss of in vitro and in vivo DNA binding (23,24), indicating that both Su(Hw) functions depend on DNA recognition. The su(Hw)f mutation encodes a full-length Su(Hw) protein with a defective ZnF10, resulting in suppression of gypsy insulator activity but retention of female fertility. This observation indicates that loss of ZnF10 separates Su(Hw) functions. Su(Hw)f binds DNA in vitro, but displays reduced in vivo chromosome occupancy (24,25). The retention of fertility in su(Hw)f mutants suggests that Su(Hw)f remains bound at SBSs essential for female germline development.

The function of Su(Hw) in female germline development is not well understood. Emerging evidence suggests that the Su(Hw) germline function and insulator roles are distinct (25). In the present study, we investigated two questions to gain an understanding of the role of Su(Hw) in oogenesis. First, we asked whether Su(Hw) association with tissue-specific binding sites might account for its restricted developmental requirement. Second, we asked whether Su(Hw)f demarcates boundaries of co-expressed gene clusters in the ovary. To address these questions, we defined genome-wide binding of wild-type and Su(Hw)f, using chromatin immunoprecipitation coupled with deep sequencing (ChIP-Seq) and extensive validation of defined SBSs by quantitative real-time PCR (ChIP-qPCR). Our studies demonstrate that Su(Hw) binding is largely constitutive during development, suggesting that its ovary function does not involve tissue-specific binding. We show that Su(Hw)f is retained at one-third of wild-type sites genome wide, suggesting that the majority of SBSs are dispensable for oogenesis. These data demonstrate that loss of a single ZnF within a multi-ZnF domain has profound effects on chromosome occupancy genome wide. We demonstrate that multiple factors influence Su(Hw)f retention, including Su(Hw) DNA-binding affinity and partnership with Mod67.2. Using the Su(Hw)f SBS dataset, we identified clusters of genes that are co-expressed in the ovary and are delimited by Su(Hw)f retained sites. Expression studies demonstrated that loss of Su(Hw) had limited effects on transcription of these genes. Based on these data, we suggest that Su(Hw) may not play a global architectural role in establishing genome regulation important for oogenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Chromatin immunoprecipitation coupled with deep sequencing

Genome-wide association of wild-type and Su(Hw)f was determined using ChIP-Seq. These experiments used chromatin isolated from ovaries dissected from females younger than 6-h old to provide an optimized balance between chromatin contributed by somatic and germ cells (25). Approximately 450 ovary pairs were used in each experiment, dissected from females raised at 25°C, 70% humidity on standard cornmeal/agar medium. Dissected material was stored in 1 × PBS at −80 C° until needed. Chromatin was prepared as described previously (25), with the following modifications. Chromatin was cross-linked by incubating ovaries in PBS with 1.8% formaldehyde. After 10 min at room temperature, samples were sonicated with the Fisher sonic dismembrator 100 flat microtip, using eight pulses of 30 s at 6 W, 90 s between pulses, producing an average size of 150–200 bp. The resulting chromatin was processed in three ways. First, 10% of the chromatin was heat treated to reverse cross-links and phenol–chloroform extracted, to generate the input DNA fraction. Second, the remaining chromatin was divided into two fractions. One fraction was incubated with guinea pig α-Su(Hw) antibody (8 μl) (25) and the other with guinea pig pre-immune serum (8 µl). Enriched DNA was obtained by incubation with protein A beads (Sigma) and phenol–chloroform extraction. Single-end libraries for Illumina high-throughput sequencing were prepared from ∼100 ng of DNA from each fraction (Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center Genetic Variation and Gene Discovery Core Facility, Cincinnati, OH, USA).

Peak detection, validation and motif analyses

Illumina Genome Analyzer IIx fastq files were processed using bowtie v. 0.12.5 software (26) to map sequence reads containing fewer than two mismatches to the fly genome (BDGP Release 5). Bowtie output files were analyzed with the Partek Genomics Suite v. 6.5 with the following parameters: the window size was 50 bp and peaks within 100 bp of each other were merged. False discovery rate (FDR) for peak detection was set to 1%. Fold enrichment values were calculated based on the reference pre-immune ChIP sample. To define the Su(Hw)-binding motif within ovary chromatin, the top 500-fold enrichment peaks identified with Partek were evaluated using MEME v.4.4.0 (27). The sequence logo was generated using WebLogo v.2.8.2 (28,29). Information contents of the consensus sequences were calculated as described by (30). All ChIP-seq data were submitted to the NIH GEO/Sequence Read Archive database, accession number GSE33052.

Validation of individual Su(Hw)-binding regions was completed using qPCR. For these experiments, chromatin was isolated from many sources, including ovaries (75 pairs per ChIP), wing discs (200 per ChIP) and third instar larval brains with attached eye and antennal discs (referred to as larval brain, 150 per ChIP). Quantification was completed using SYBR green (BioRad) using primers designed to amplify 100–200 bp fragments centered on a Su(Hw)-binding motif (available upon request). The following formula (% input = 2Ct(input) − Ct(IP) × 1/DF × 100, where DF is the dilution factor between IP and input samples) was used to calculate ChIP/input cycle threshold change ratios. All analyses were performed in at least two biological replicates.

To define the degree of conservation among SBSs, Patser v.3b (31) was used to scan each peak region to identify highest scoring SBS. The position-specific weight matrix (PSWM) used by Patser was obtained from MEME using top 500 wild-type peaks. After determining the position of the SBS within the binding peak, we generated a phastCons score profile encompassing the highest scoring SBSs (20 bp of the binding site and 10 bp on each side). PhastCons score profiles were aligned and the median score at each position was used for further analysis.

Analyses of overlap between SBSs with chromatin proteins

Analyses were undertaken to determine whether SBSs overlap with binding of Mod67.2 and CP190. Binding peak data for these factors were downloaded from the modENCODE project website (http://modencode.org/). Two binding peaks were considered overlapping if the peak center distance was shorter than half of the longer peak. This criterion ensures that the shorter peaks fall within the longer peak. Statistical significance of binding site overlap was determined using 1000 random sets of binding peaks; each random set had the same length distribution as the real data. The P-value of site overlap was empirically determined as the fraction of random sets that have equal or larger number of overlapping sites.

Analysis of Su(Hw) binding

The in vitro DNA-binding properties of wild-type [Su(Hw)+] and Su(Hw)f were determined using full-length His-tagged proteins purified from Escherichia coli DE3 cells, using a protocol described previously (11). SBSs were isolated by PCR amplification of Canton S genomic DNA and cloned into StrataClone vectors (Agilent Technologies). Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSAs) were used to define interactions between purified Su(Hw)+ or Su(Hw)f with DNA, using DNA-binding conditions described previously (11). EMSA assays were used to determine the apparent association constant (M−1) for Su(Hw)+ and Su(Hw)f for selected 32P-labeled SBSs (Supplementary Figure S2), using the non-linear least-squares analysis of a Langmuir binding equation for non-cooperative binding using Kaleidagraph (Synergy Software) (32). Interactions of Su(Hw)+ or Su(Hw)f with bacterially purified full-length His-tagged Mod67.2 and CP190 were analyzed using EMSAs. In these experiments, equal molar amounts of Su(Hw)+ or Su(Hw)f were incubated with CP190 and Mod67.2 (Supplementary Figure S1) in the presence of a 32P-labeled SBS. Total protein was normalized by addition of bovine serum albumin.

Polytene chromosome staining

Salivary glands were dissected from wandering third instar larvae into Cohen Buffer (10 mM MgCl2, 25 mM Na2GlyceroPO4, 3 mM CaCl2, 10 mM KH2PO4, 0.5% NP40, 30 mM KCl, 160 mM Sucrose), fixed for 3 min in formaldehyde (100 mM NaCl, 2 mM KCl, 2% Triton X-100, 2% formaldehyde, 10 mM NaPO4 pH 7.0) and 2 min in squashing solution (45% acetic acid, 2% formaldehyde). Glands were squashed and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Following washes, slides were stained for 1–2 h with guinea pig anti-Su(Hw) (1:250), sheep anti-CP190 (1:100) and chicken anti-Mod67.2 (1:500) antibodies in PBS containing 10% normal goat serum or 10 mg/ml non-fat dry milk in the case of CP190, 5 mg/ml gamma globulins. Slides were incubated 1 h with goat anti-guinea pig Alexa Fluor 488 (A11073) at a 1:1000 dilution. Following DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) staining, slides were mounted in Vectashield H-1000 (Vector Laboratories) and imaged using a Leica DMLB or Zeiss 710 confocal microscope. Images were processed using ImageJ and Adobe Photoshop.

Quantitative PCR analyses of ovary gene expression

Ovaries were dissected from virgin females 4–6-h post-eclosion. Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol (Invitrogen), DNase treated with DNA free kit (Ambion) and reverse-transcribed using High Capacity cDNA kit with random hexamer primers (Applied Biosystems). Quantitative PCR analyses were performed using iQ SYBR green supermix (BioRad). Three independent biological replicates were analyzed. Expression level of each gene was determined relative to RpL32 as an internal control (ΔCt).

RESULTS

Genome-wide mapping of SBSs in the ovary

Previous genome-wide mapping of Su(Hw) in two embryonic cell lines suggested cell type-specific binding (33). These observations indicated that the restricted developmental requirement for Su(Hw) may result from tissue-specific binding in the ovary that contributes unique regulatory functions. To test this postulate, we used ChIP-Seq to define SBSs in the ovary. Chromatin was isolated from ovaries dissected from females <6 h old, because these ovaries contain a nearly equal contribution of chromatin from germ cells and somatic cells. The α-Su(Hw) ChIP sample generated 21 million uniquely mapped tags, with ∼13 and ∼14 million obtained from ChIP with pre-immune serum and input chromatin, respectively (Supplementary Table S1). Using a 1% FDR, we identified 2932 SBSs with a median peak size of 293 bp (Figure 1A, Supplementary Table S2). To validate the ovary SBS dataset, we completed ChIP-qPCR analysis on newly isolated ovary chromatin. In these studies, we analyzed four sets of six SBSs representing each enrichment quartile and six genomic regions that were negative in our ChIP-Seq data and lacked a Su(Hw)-binding motif. These analyses demonstrated that all 24 ChIP-seq SBSs displayed 1% or greater enrichment relative to input (Figure 1B), with the level of SBS enrichment in the ChIP-qPCR analysis generally related to that found in the ChIP-seq data. Comparison of ChIP-qPCR values for true SBSs relative to the negative control regions indicates that a 1% input discriminates between real and background Su(Hw) binding (Figure 1B). For this reason, we used this empirically defined value to evaluate significant Su(Hw) occupancy in subsequent experiments. Together, these experiments demonstrate that we have generated a high-quality dataset of wild-type Su(Hw) ovary binding sites.

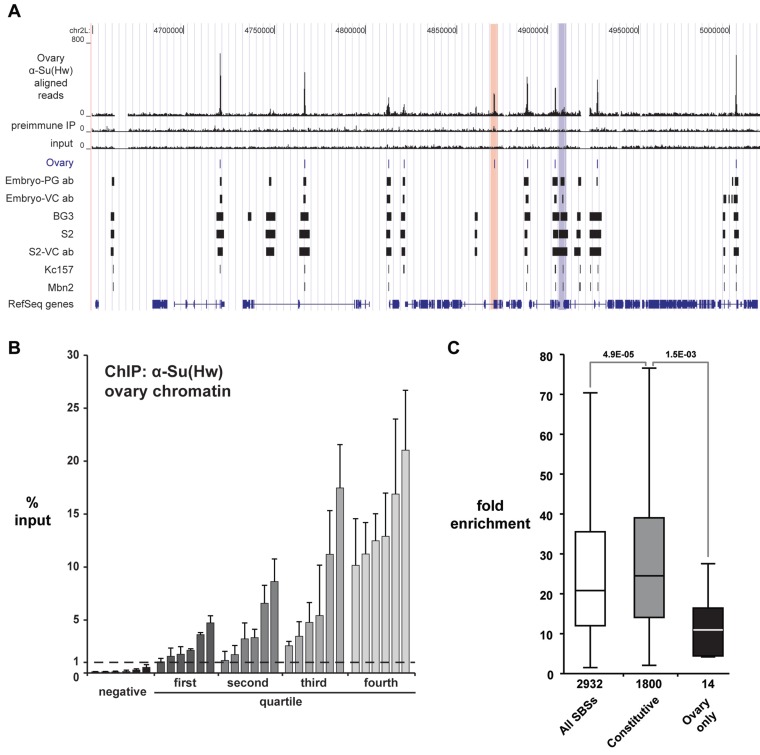

Figure 1.

ChIP-Seq analysis of SBSs in the ovary. (A) Shown is a UCSC Genome Browser view of a representative 360 kb region of chromosome 2L. Several tracks are shown, including Su(Hw)WT ovary ChIP-Seq reads, the pre-immune serum IP control reads, and the input chromatin control reads. The ovary peaks (1% FDR) defined from our data are compared to SBSs identified in (33,34). These latter datasets include peaks identified in embryos using the PG or VC antibody and four cell lines (BG3, S2, Kc157 and Mbn2). Examples of ovary-gained and ovary-lost sites are highlighted (red and blue bars). (B) Shown are data from validation studies of SBSs identified in ChIP-seq. ChIP-qPCR was completed on two biologically independent chromatin isolations, distinct from that used for ChIP-seq. SBSs are arranged into four quartiles based on the level of Su(Hw) occupancy predicted from ChIP-Seq data. Six randomly chosen SBSs from each quartile were tested. Error bars indicate standard deviation. Negative controls represent sites that lack a Su(Hw)-binding motif. These sites were not identified in the ChIP-Seq dataset. (C) Box plot of fold enrichment values of all SBSs identified in the ovary (white), SBSs identified in all genome-wide studies (constitutive, gray), and SBSs identified only in the ovary dataset (ovary only, black). Boxes represent the 25–75 percentile interval, with the median enrichment indicated by the line. Whiskers represent the non-outlier range. P-values of Student’s t-test are indicated.

To determine whether Su(Hw) was associated with ovary-specific binding sites, we defined the extent of overlap between our ovary dataset and those generated from ChIP-Chip studies of chromatin isolated from embryonic and larval cells (Figure 1A, Supplementary Table S2) (33–35). These analyses showed that ∼99% of the ovary SBSs were found in at least one other dataset, with nearly two-thirds found in all sets (61.4%, ∼1800 SBSs; referred to as constitutive SBSs). As a result, only 14 (0.5%) of SBSs were found exclusively in the ovary dataset (referred to as ovary-gained sites), while 325 (∼11%) were not found in the ovary dataset (referred to as ovary-lost sites). Together, these data predict that few, if any, SBSs are ovary specific.

We reasoned that differences among SBS datasets might represent small, but functionally important tissue-specific changes in chromosome association. Alternatively, distinct SBS identification may be related to technical differences in experimentation, such as antibody source or analysis software. To distinguish between these possibilities, we compared the fold enrichment values for the SBS classes, which revealed that the median fold enrichment for the constitutively bound sites was significantly higher than that of the ovary-gained sites (Figure 1C). These observations imply that Su(Hw) occupancy at ovary-gained sites is at the threshold for detection, accounting for the absence of these sites in other datasets. To determine whether the ovary-gained sites were reproducibly identified, we randomly selected ten sites for direct analysis by ChIP-qPCR. As controls, we analyzed 20 constitutive SBSs and 20 ovary-lost sites (Figure 2A). We found enrichment values for all constitutive sites at or above the 1% input threshold. Whereas two constitutive sites showed occupancy at 1–3% input, the rest were above 5% input. In contrast, the majority of ovary-gained sites (7/10) displayed enrichment near the 1% threshold, with only one site above 5%. These data suggest that ovary-gained sites are valid, but low occupancy SBSs. Analysis of ovary-lost sites showed that the majority (17/20) were below the 1% threshold. These findings confirm that our peak detection was robust, possibly because ChIP-Seq has a greater dynamic range than ChIP-Chip, which permitted better discrimination of ChIP peaks.

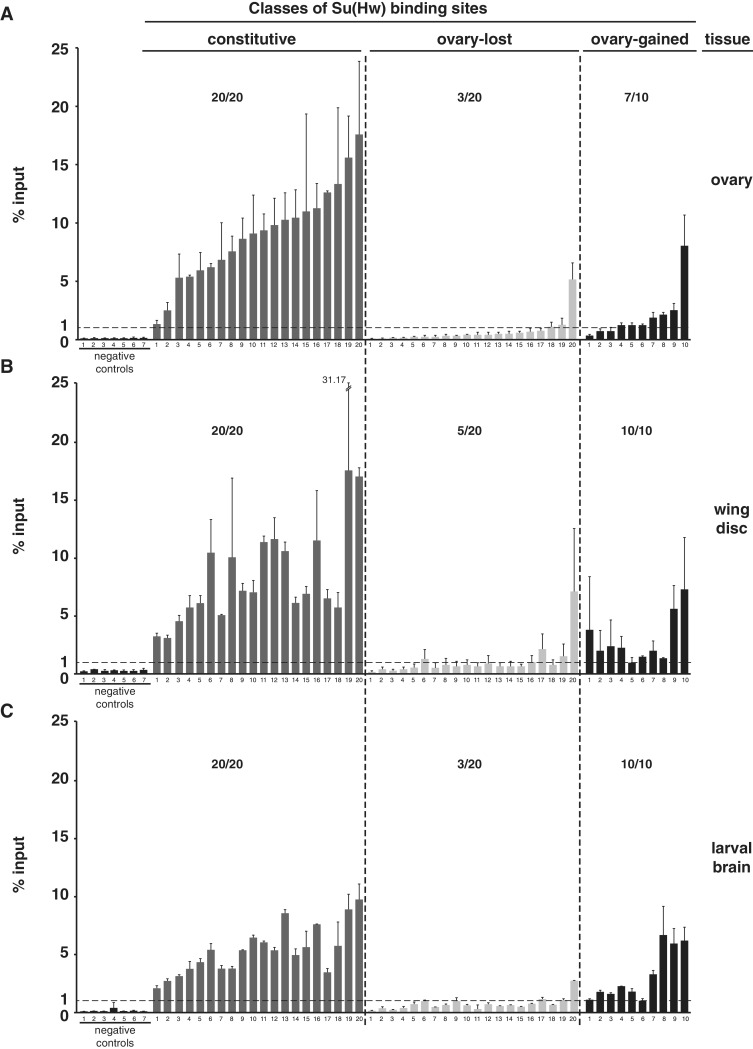

Figure 2.

Su(Hw) binding is largely constitutive. (A–C) Shown is ChIP-qPCR data analyzing Su(Hw) binding to the same sets of SBSs in chromatin obtained from the ovary (A), third instar wing disc (B) and third instar larval brain with eye and antennal disc (C). Negative controls represent sites that lack a Su(Hw)-binding motif and were not identified in the ChIP-Seq dataset. The dashed line indicates 1% input threshold. SBSs tested are divided into constitutive (20 sites), ovary-lost (20 sites) and ovary-gained (10 sites). Averaged values of two biological replicates are shown, error bars indicate standard deviation. For each experiment, the ratio represents the number of SBS above 1% input level over the total number of sites tested.

Our analyses identified a small number of ovary-gained sites. To determine whether these SBSs are tissue specific, we tested Su(Hw) occupancy at these sites in two other tissues. To this end, we conducted ChIP-qPCR using chromatin isolated from third instar larval wing discs and brains, testing Su(Hw) occupancy at the same set of constitutive, ovary-lost and ovary-gained SBSs (Figure 2B and C). Again, all constitutive SBSs were bound above the 1% threshold, with the level of occupancy generally consistent between tissues. The majority of ovary-lost SBSs (15/20 or 17/20) were below the 1% input threshold in both tissues, with the remaining SBSs displaying enrichment near 1% input. These findings suggest that many ovary-lost sites are low occupancy sites at the threshold for detection or possibly false positives in other datasets. MEME analyses showed that half of the ovary-lost sites contain a match to the Su(Hw) DNA-binding motif (data not shown), supporting that many sites in this group are not false positives. ChIP-qPCR analysis of the ovary-gained SBSs showed that many were bound in wing disc and brain chromatin, although signals for most were near the 1% input threshold. Based on these data, we conclude that SBSs originally identified as ovary-specific are found in other tissues, suggesting that Su(Hw) binding is largely constitutive throughout development.

Analysis of properties of SBS subclasses

SBSs fall into three classes based on partnership with the gypsy insulator proteins Mod67.2 and CP190 (34). These include (i) SBSs that do not bind the gypsy partners (SBS-O), (ii) SBSs with CP190 only (SBS-C) and (iii) SBSs with CP190 and Mod67.2 (SBS-CM) (34). While bulk properties of SBSs are reported (33), no studies have evaluated whether SBSs display class-specific properties. Two observations suggest that SBSs identified in our ovary ChIP-seq studies could be used as the basis for further understanding properties of SBS subclasses. First, we have demonstrated that Su(Hw) binding is largely constitutive (Figure 2), suggesting that our ovary SBSs dataset accurately reflects Su(Hw) binding genome wide. Second, our previous studies indicate that Su(Hw) partnership with Mod67.2 and CP190 is largely unchanged during development (25). This conclusion is based on immunohistochemical analyses of nurse cell polytene chromosomes obtained from the ovarian tumor mutant, which showed that co-localization of Su(Hw), Mod67.2 and CP190 parallels that observed on salivary gland polytene chromosomes (25). Further, direct qPCR analyses demonstrated that ∼90% (10/11) of SBSs that bound CP190 in embryos also bound CP190 in the ovary (25). Taken together, these data imply that the Su(Hw) partnership with Mod67.2 and CP190 is maintained in the ovary.

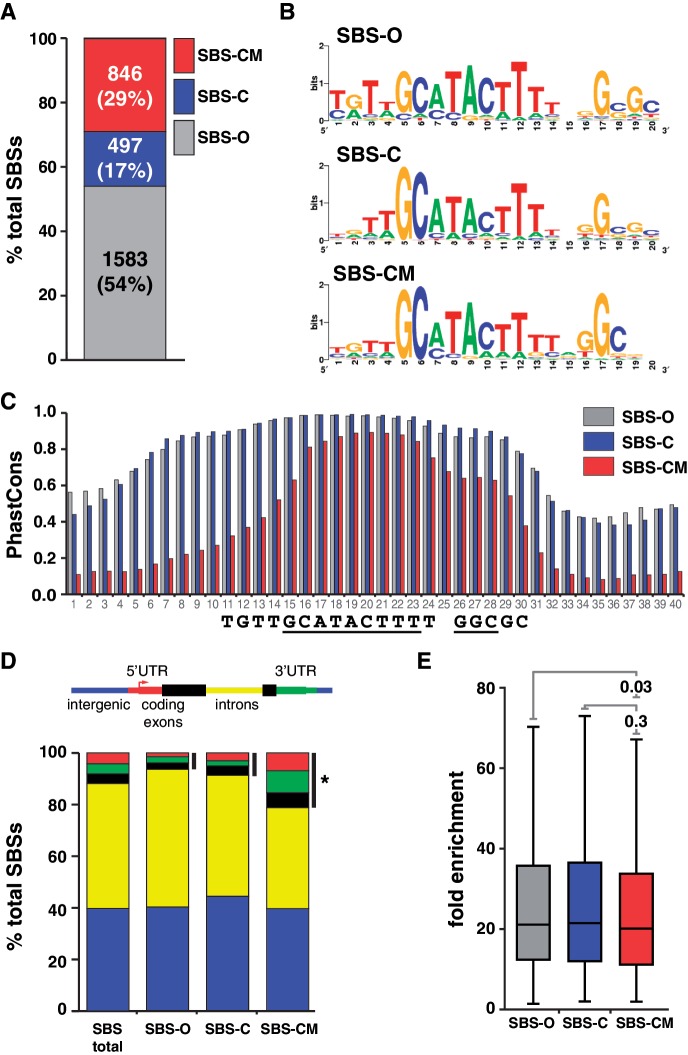

Several properties of SBS subclasses were tested. First, we determined the distribution of SBSs among the three classes. We found that SBS-O sites represent the most prevalent class, corresponding to 54% of SBSs, while SBS-CM sites were 29% and SBS-C sites were 17% (Figure 3A). These observations imply that most SBSs are not associated with the gypsy insulator proteins. Second, we used the DNA motif search program MEME to define the sequence of the Su(Hw)-binding motif associated with each class. These analyses revealed that SBS subclasses display only minor differences in information content (Figure 3B), indicating that changes in the binding motif are not responsible for differences in partner association. Third, we defined the median phastCons scores for 40 nucleotide regions centered on the Su(Hw)-binding motif to evaluate sequence conservation among SBS classes. These analyses showed that SBS-O and SBS-C sites are more conserved than SBS-CM sites, with the most striking differences corresponding to nucleotides upstream of the Su(Hw)-binding motif (Figure 3C). These data imply that additional constraints are placed upon Su(Hw) occupancy in the absence of Mod67.2. MEME analyses of SBS-O and SBS-CM SBSs failed to identify a second conserved sequence within these upstream regions, indicating the absence of a common binding site for another protein. Fourth, we defined the distribution of ovary SBS classes relative to gene features. Interestingly, these analyses uncovered class-specific differences (Figure 3D). We found that SBS-CM sites are significantly enriched within 5′-, 3′-UTRs and exons (P = 2.0e-12). This finding that the gypsy insulator-like subclass is enriched at promoters is consistent with predictions that insulators may have evolved from promoters (2,36). Fifth, we compared fold enrichment values of SBSs in each subclass to determine whether Su(Hw) occupancy differed among SBS classes. We found that each SBS subclass displayed a similar median fold enrichment, indicating that Su(Hw) does not display preferential occupancy at one SBS class (Figure 3E).

Figure 3.

Distinct classes of SBSs are found in the genome. (A) Shown is a bar plot of the proportion of SBS-O, SBS-C and SBS-CM sites in the genome. Number and percentage of sites are indicated. (B) Shown are the sequence logos of Su(Hw)-binding motifs derived from SBS-O, SBS-C and SBS-CM sites. (C) Shown are the median PhastCons scores of the 40 nt encompassing the Su(Hw) consensus binding motif of SBS-O, SBS-C and SBS-CM sites. Numbers on x-axis indicate nucleotide position; sequence logo below is aligned to the plot. (D) Shown are the genomic distributions associated with total and SBS subclasses. Black bars indicate binding sites mapped to the 5′-, 3-UTRs and coding exons. *P = 2.002e-12 by two-proportion z-test. (E) Shown are the box plots corresponding to the fold enrichment values of the three subclasses of SBSs. Within each box, the black line indicates the median enrichment, boxes and whiskers represent 25–75 percentile interval and non-outlier range. P-values of Student’s t-test are indicated.

Effects of the gypsy insulator proteins on Su(Hw) occupancy

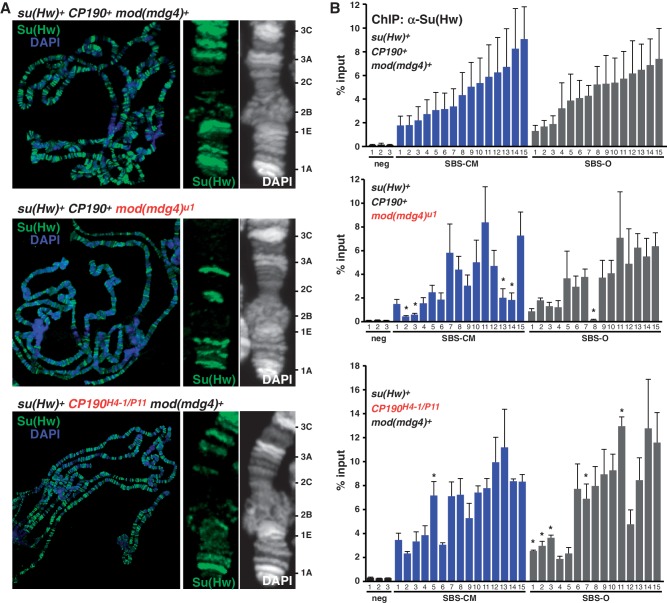

Nearly half of SBSs associate with one or both of the gypsy insulator proteins Mod6.72 and CP190. We investigated whether these proteins were involved in Su(Hw) chromosome association. To this end, we examined Su(Hw) binding on salivary gland polytene chromosomes isolated from mod(mdg4) and Cp190 mutant larvae. This strategy was selected because salivary gland chromosomes have been widely used to provide mechanistic insights into genome-wide protein recruitment (37–41). Immunohistochemical staining of Su(Hw) on mod(mdg4) mutant chromosomes demonstrated that Su(Hw) localization was reduced (Figure 4A), a finding consistent with previous reports (42,43). These observations suggest that Mod67.2 may facilitate Su(Hw) chromosome association or retention. To investigate the impact of Mod67.2 on Su(Hw) retention, we randomly selected 15 SBS-CM and 15 SBS-O sites. We predicted that if Mod67.2 improved Su(Hw) association, then we would observe decreased Su(Hw) occupancy specifically at SBS-CM sites, whereas changes at SBS-O sites would reflect general chromatin changes in mod(mdg4) mutants. Su(Hw) occupancy was defined using qPCR analyses, revealing that loss of Mod67.2 decreased Su(Hw) occupancy at 25% (4/15) of SBS-CM sites, while retention at ∼6% of SBS-O sites was affected (Figure 4B). These data support a role for Mod67.2 in facilitating Su(Hw) chromosome association at SBS-CM sites. In contrast, immunohistochemical analysis of Su(Hw) binding on Cp190 mutant polytene chromosomes revealed a minimal loss of Su(Hw) (Figure 4A). Direct tests of Su(Hw) occupancy ∼6% of SBS-CM and 30% of SBS-O were increased (Figure 4). These data suggest that enhanced Su(Hw) association in Cp190 mutants may be due to indirect effects on chromatin structure. Previous studies demonstrated that CP190 largely localizes to promoters (44), suggesting that these indirect effects may be due to changes in gene expression that affect chromatin structure. Taken together, our data indicate a role for Mod67.2, but not CP190, in facilitating Su(Hw) binding to chromatin.

Figure 4.

Mod67.2 protein facilitates chromosome association of Su(Hw). (A) Shown are the polytene chromosomes from third instar larval salivary glands of su(Hw)WT CP190WT mod(mdg4)WT, su(Hw)WT CP190H4−1/P11 mod(mdg4)WT and su(Hw)WT CP190WT mod(mdg4)u1 backgrounds stained with α-Su(Hw) antibody (green) and DAPI (blue/white). For each genotype, the tip of the X chromosome is enlarged, with cytological positions indicated on the right. (B) Shown are ChIP-qPCR analyses of Su(Hw) binding in ovaries of wild-type (top), mod(mdg4)u1 (middle) or CP190H4−1/P11 (bottom) mutants. SBSs that were analyzed fall into two subclasses, SBS-CM (blue) and SBS-O (gray). Error bars indicate standard deviation of two to four independent biological replicates. *P ≤ 0.01 (Student’s t-test).

Mutation of ZnF10 causes widespread loss of Su(Hw) binding

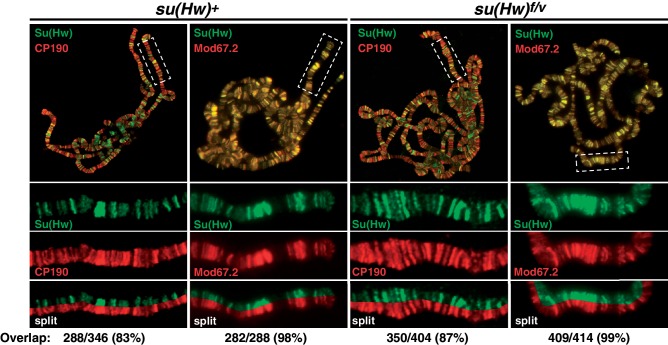

Su(Hw)f carries a defective ZnF10. To understand whether loss of ZnF10 alters Su(Hw) properties by changing its association with the gypsy insulator proteins, we studied the ability of Su(Hw)f to recruit Mod67.2 and CP190 to polytene chromosomes isolated from salivary glands. Previous studies documented extensive co-localization of Su(Hw) and the gypsy insulator proteins on salivary gland chromosomes (16,42,43,45,46), with near complete co-localization with Mod67.2 and an extensive but lower co-localization with CP190. Polytene chromosomes isolated from su(Hw)+ and su(Hw)f/v larvae were stained with antibodies against Su(Hw) and co-stained with antibodies against either Mod67.2 or CP190. Based on the quantification of banding patterns obtained from split chromosome analyses, we find that Su(Hw)f co-localized with Mod67.2 at nearly all genomic locations (Figure 5). These data indicate that loss of ZnF10 does not strongly affect Mod67.2 in vivo association, although subtle differences may not be detected. The nearly unchanged Su(Hw)f recruitment of Mod67.2 is consistent with observations that a carboxyl-terminal region of Su(Hw) outside of the zinc finger domain is required for Mod67.2 association (42,47). Similarly, we find that Su(Hw)f co-localization with CP190 is indistinguishable from wild-type Su(Hw), implying that loss of ZnF10 does not affect CP190 in vivo association, although subtle differences may not be detected. To extend our analyses of Su(Hw)f partnership with Mod67.2 and CP190, we used an EMSA assay with purified recombinant proteins to investigate effects of loss of ZnF10. Incubation of Su(Hw)+ with Mod67.2 or CP190 generated a supershift that becomes more pronounced in the presence of both proteins (Supplementary Figure S1). The observed supershift parallels that previously reported in an EMSA assay documenting associations between wild-type Su(Hw) and CP190 (16). Incubation of Su(Hw)f with recombinant gypsy insulator proteins produced a similar supershift. Taken together, these data support the conclusion that loss of ZnF10 does not alter Su(Hw)f association with the gypsy insulator proteins.

Figure 5.

Loss of ZnF10 does not affect Su(Hw) recruitment of gypsy insulator proteins. Shown are third instar larval su(Hw)WT (left) and su(Hw)f/v (right) polytene chromosomes co-stained with antibodies for Su(Hw) and either CP190 or Mod67.2. The top panels represent merged images obtained for the indicated whole genome chromosome spread. The boxed area in each merged image is expanded below, showing the banding pattern for each protein alone and a split of the merged image. The degree of overlap of Su(Hw) with either CP190 or Mod67.2 is shown, with bands counted from at least three independent chromosome spreads.

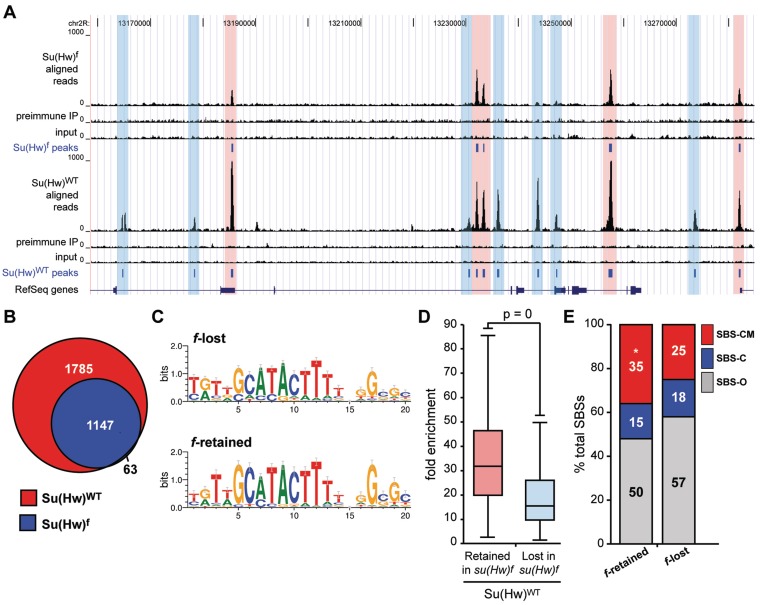

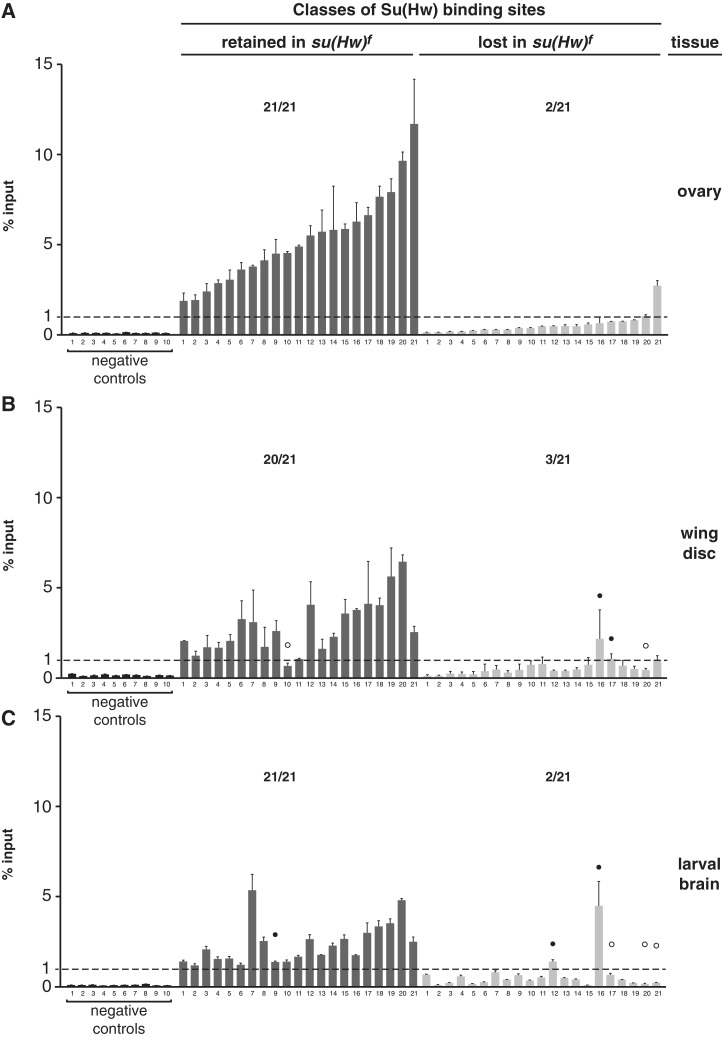

Previous studies demonstrated that ZnF10 mutant loses in vivo occupancy of Su(Hw) at the gypsy insulator and some, but not all, non-gypsy SBSs (24,25). As su(Hw)f females are fertile, we reasoned that genome-wide mapping of Su(Hw)f chromosome association would provide insights into the germline function of Su(Hw). To this end, we identified Su(Hw)f SBSs in the ovary. For Su(Hw)f, the α-Su(Hw) IP sample generated over 20.6 million uniquely mapped tags, with ∼20 million obtained both from ChIP with pre-immune serum and input chromatin (Supplementary Table S1). Using a 1% FDR, we identified 1210 SBSs with a median peak size of 249 bp (Figure 6A). The Su(Hw)f SBS dataset was validated using ChIP-qPCR analyses of a collection of randomly selected Su(Hw)f SBSs (referred to as f-retained) and SBSs that were lost (referred to as f-lost). These analyses showed that Su(Hw)f bound all f-retained sites above the 1% input threshold, whereas only two f-lost sites were above this value (Figure 7A). These experiments demonstrate that a high-quality Su(Hw)f SBS dataset was obtained.

Figure 6.

Su(Hw)f protein retains association with a third of wild-type SBSs. (A) Shown is a UCSC Genome Browser view of a representative 360 kb region of chromosome 2L. Several tracks are shown, including Su(Hw)f ovary ChIP-Seq reads, Su(Hw)f pre-immune serum control reads, and Su(Hw)f input DNA control reads. The ovary peaks (1% FDR) defined from our the Su(Hw)f data are compared with tracks showing the Su(Hw)WT ovary ChIP-Seq reads, Su(Hw)WT pre-immune serum control reads, Su(Hw)WT input DNA control reads and the Su(Hw)WT ovary peaks. For reference, the track of RefSeq genes is shown. Highlighted are f-lost sites (blue) and f-retained sites (red). (B) Venn diagram of ChIP-Seq mapped ovary Su(Hw)WT and Su(Hw)f-binding sites. (C) Sequence logos of Su(Hw)-binding motifs derived using top 500 f-lost and top 500 f-retained SBSs. (D) Box plot of fold enrichment between chromatin immunoprecipitated with α-Su(Hw) antibody and pre-immune IgG from su(Hw)wt ovaries. Box plot parameters are the same as in Figure 1. (E) Distribution of f-retained and f-lost SBSs based on the co-localization with the gypsy insulator protein partners. *P = 2.29e-09 (two-proportion z-test).

Figure 7.

Su(Hw)f binding is retained at tissue-specific sites. (A–C) ChIP-qPCR analyses of Su(Hw)f binding to the same set of 21 sites in chromatin isolated from the ovary (A), third instar wing disc (B) and third instar larval brain with eye and antennal disc (C). Negative controls represent sites that lack a Su(Hw)-binding motif and were not identified in the ChIP-Seq dataset. The dashed line indicates 1% input threshold. SBSs are divided into f-retained (dark gray, 21 sites) and f-lost (light gray, 21 sites). Averaged values of two biological replicates are shown, error bars indicate standard deviation. For each experiment, the ratio represents the number of SBS above 1% input level over the total number of sites tested. White and black circles indicate tissue-specific f-lost and f-retained sites, respectively.

Su(Hw)f SBSs largely overlapped with wild-type SBSs (95%; Figure 6B). To understand how loss of ZnF10 affects in vivo Su(Hw) occupancy, we defined the sequence motif associated with f-retained sites. Wild-type Su(Hw) [Su(Hw)+] binds a 20-bp motif containing two highly conserved 9 and 3 bp cores (48). Using the DNA motif search program MEME, we found that f-retained sites had a similar, but more restricted binding motif, with a higher information content [20.9 bits for Su(Hw)f relative to 15.0 for Su(Hw)+; Figure 6C]. These findings imply that the binding specificity of Su(Hw) is not changed in the absence of ZnF10. Instead, in vivo selection of binding sites is constrained.

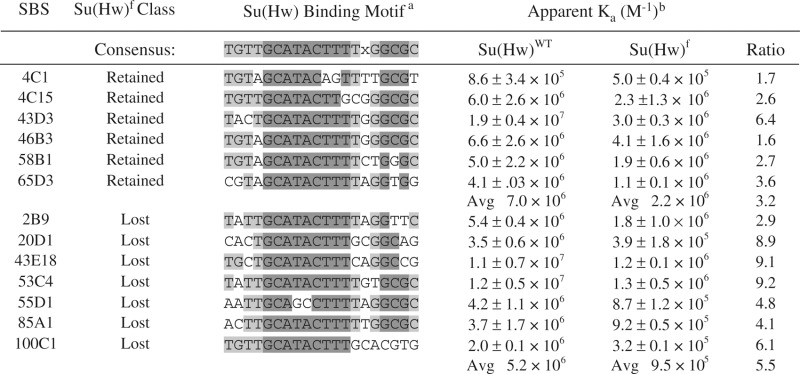

Comparison of Su(Hw)+ occupancy at Su(Hw)f retained and lost sites showed that f-retained sites had a higher fold enrichment (Figure 6D). These data indicated that retention might be related to DNA-binding affinity. Previous studies had demonstrated that Su(Hw)+ and Su(Hw)f had nearly identical in vitro DNA-binding affinities at the 1A-2 and gypsy insulators, even though in vivo binding at both was lost (24). We postulated that the presence of clustered binding motifs in these insulators might have masked differences in DNA-binding affinity. As nearly all endogenous sites contain single Su(Hw)-binding motifs, we reasoned that single motif regions might display differences in binding between the wild-type and mutant proteins. To this end, we randomly selected f-retained and f-lost sites and used EMSA assays to define apparent binding affinities for Su(Hw)+ and Su(Hw)f. We found that Su(Hw)+ demonstrated an ∼22-fold range in binding affinities between single motif SBSs (compare sites 4C1 and 43D3; Supplementary Figure S2; Table 1). In general, these studies showed that the apparent binding affinity of Su(Hw)+ for f-retained sites was greater than f-lost, differing by an average of ∼1.4-fold. Tests of Su(Hw)f revealed that this mutant had reduced binding at all sites, showing ∼1.6 to 9.2-fold lower apparent binding affinities than observed for Su(Hw)+. In general, Su(Hw)f showed reduced binding at f-lost sites compared to f-retained, differing by an average of ∼2.3-fold. Even so, the apparent binding affinities for Su(Hw)f at f-retained and f-lost sites overlap, suggesting that binding affinity is not always predictive of Su(Hw)f retention.

Table 1.

Summary of in vitro Su(Hw) and Su(Hw)f DNA-binding analyses

|

aA match to the Su(Hw) consensus motif is noted using shading, where dark gray identifies a match to a nucleotide in the conserved 9 and 3 bp cores and light gray identifies a match of a residue outside of the conserved cores. X represents any nucleotide. bKa, apparent association constant, where M−1 is reverse molar.

Tissue-specific effects on Su(Hw)f retention

Based on the absence of a strict correlation between the in vitro and in vivo binding data, we postulated that chromatin accessibility might impact Su(Hw)f retention. As a first step to address this prediction, we determined whether Su(Hw)f retention was correlated with gene structure or one of the nine global chromatin states defined by the ModEncode project (35). These analyses failed to uncover any significant connection with these features (Supplementary Figure S3). Next, we reasoned that if decreased chromatin accessibility were responsible for differential Su(Hw)f binding, then Su(Hw)f binding might show tissue-specific differences in site occupancy, as the chromatin landscapes are cell type specific. This possibility was tested using ChIP-qPCR of chromatin isolated from larval wing disc and brain tissues. We found largely unchanged Su(Hw)f occupancy at f-retained sites in these cell types, while occupancy at f-lost sites showed tissue-specific differences (Figure 7B). In wing discs, we found that 14% (3/21) of the ovary f-lost sites were bound, while in brain, 9.5% (2/21) of the ovary f-lost sites were bound. These findings suggest minor differences in Su(Hw)f occupancy between tissues.

As SBS subclasses show differences in enrichment at gene features, we investigated whether Su(Hw)f retention differed among these subclasses. Parsing f- retained sites into subclasses showed that SBS-CM sites were over-represented, while the proportion of SBS-C and SBS-O sites decreased (P = 2.29e-09; Figure 6E). This profile links Su(Hw)f retention with the presence of Mod67.2, a finding that is consistent our demonstration that Mod67.2 enhances Su(Hw)+ occupancy (Figure 4).

Ovary expression of gene clusters does not depend on Su(Hw) defined boundaries

The Drosophila genome is organized into clusters of co-regulated genes (49–52). We reasoned that if the germline function of Su(Hw) depended on an insulator activity, then Su(Hw) might be required for proper expression of co-regulated ovary gene clusters. To test this prediction, we used the FlyAtlas database (53) to identify clusters of two or more genes that showed 2-fold or greater up- or down-regulation in the ovary relative to whole fly. From this analysis, we found 772 down- and 219 up-regulated gene clusters, which we refer to as ovary-repressed and ovary-expressed gene clusters, respectively. The presence of a larger number of repressed gene clusters is consistent with observations that tissue-specific gene expression involves widespread transcriptional silencing (54).

Potential Su(Hw) regulated gene clusters were identified using our ovary SBS datasets. We postulated that if the critical ovary function of Su(Hw) was to define transcriptional domains, then the ovary gene clusters should be delimited by an SBS that retained binding of the fertile Su(Hw)f mutant. Using these parameters, the number of clusters was reduced to 25 down- and 3 up-regulated gene clusters. Of the 34 f-retained sites bordering these domains, nearly half (47%) were gypsy insulator-like SBS-CM sites, with the remaining corresponding to SBS-O (44%) and SBS-C (9%). These observations imply an over-representation of the SBS-CM sites at the borders of gene clusters.

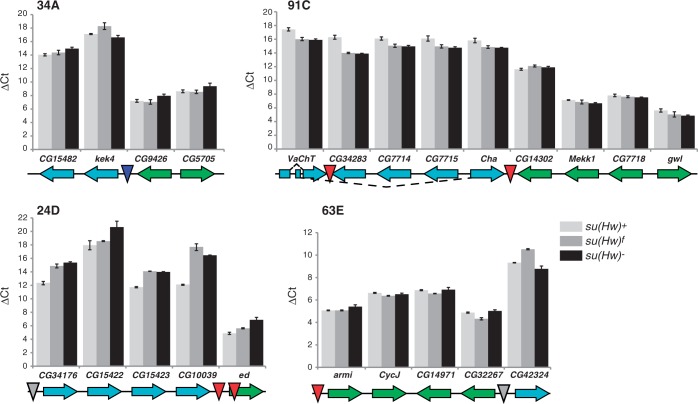

To test whether Su(Hw) is required for transcriptional regulation of these ovary-regulated gene clusters, we measured RNA levels of genes in and neighboring the clusters, in a su(Hw) wild-type and mutant backgrounds (Figure 8). We predicted that if the essential germline function of Su(Hw) involved formation of a chromatin insulator, then loss of Su(Hw) would lead to cross-regulatory interactions between clustered and neighboring genes, resulting in an equalization of gene expression across the SBS boundary. In our studies, gene expression was measured in RNAs isolated from newly eclosed wild-type and mutant ovaries. These ovaries were chosen for two reasons. First, newly eclosed ovaries contain oocytes developed only to early stages of oogenesis, so that wild-type ovaries do not contain developmental stages lost in su(Hw) mutants. Second, newly eclosed su(Hw) mutant ovaries display defective development, suggesting that gene expression changes caused by loss of Su(Hw) should be manifest in these ovaries. QPCR analyses of su(Hw)+ RNA confirmed the predicted patterns of gene expression, wherein genes in up-regulated clusters had higher RNA levels than down-regulated clusters, displaying 4- to 128-fold higher levels of expression than neighboring genes (Figure 8). Measuring RNA levels in su(Hw) mutant backgrounds revealed that loss of Su(Hw) caused limited changes to expression of the clustered genes, with the exception of cluster 24D where all repressed genes demonstrated further decreased RNA accumulation. Importantly, all clusters retained the distinction between ovary-expressed and ovary-repressed genes in the su(Hw) null mutant background, suggesting that the ovary function of Su(Hw) may not involve formation of insulators to establish domains of gene expression.

Figure 8.

Loss of Su(Hw) has limited effects on transcription of clusters of co-regulated genes in the ovary. Gene expression studies were completed on four gene clusters (34A, 91C, 24D, 63E). Genes showing up-regulated in the ovary relative to other tissues are labeled in green, while genes that are down-regulated in the ovary are labeled in cyan. The orientation of the arrow denotes direction of transcription. The position of the SBS is shown by the inverted triangle, where SBS-O sites are shown as gray, SBS-C sites as blue and SBS-CM sites as red. Bar graphs of ΔCt values obtained from qPCR analyses of each gene relative to the housekeeping gene RpL32. RNAs analyzed were isolated from newly eclosed ovaries from su(Hw)WT (light gray), su(Hw)f (intermediate gray) and su(Hw)null (black) females. Error bars indicate standard deviation of three independent biological replicates.

DISCUSSION

Su(Hw) is a broadly expressed transcription factor that is required for oogenesis (21,25). Much of our understanding of Su(Hw) function has been obtained through investigation of the gypsy insulator. These studies have led to the concept that Su(Hw) is an architectural protein involved in establishing higher order chromosomal structure critical for regulation of gene expression (45). However, emerging evidence suggests that the function of Su(Hw) extends beyond that of an insulator protein, including the recent demonstration that 1A-2, a cluster of two SBSs, is required for activation of yar, a non-coding RNA gene (55). These data suggest that Su(Hw) has multiple functions in the genome.

The function of Su(Hw) in the ovary

Previous studies estimate that between five to eighteen percent of SBSs are cell type specific (33), with evidence that 1–3% of SBSs are developmentally regulated (56). Here, we used ChIP-seq coupled with extensive ChIP-qPCR to show that Su(Hw) chromosome occupancy is largely constitutive throughout development (Figures 1 and 2). While we identified a small set of ‘ovary-specific’ SBSs among the low fold enrichment SBSs, we showed that these sites are occupied in non-ovary tissues. Our data are consistent with the previous analysis of SBSs in the three megabase alcohol dehydrogenase region, in which Su(Hw) binding was conserved between different tissues (48). Our studies provide a cautionary note for investigations relying solely on computational evaluation of high-throughput genomic datasets, as we find that extensive validation is required to establish confident binding thresholds needed for data interpretation.

The ovary-specific developmental requirement for Su(Hw) may be explained based on its function at the gypsy insulator. The insulator properties of Su(Hw) suggest that oogenesis may require establishment of domain boundaries that permit appropriate gene expression in the ovary. To test this postulate, we defined genome-wide binding sites for Su(Hw)f, a mutant isoform that lacks insulator activity, but retains fertility. These studies revealed that Su(Hw)f was retained at only one third of wild-type sites (Figure 6). Ostensibly, these observations are surprising for an architectural protein, as two-thirds of SBSs can be lost without effects on essential functions needed for fertility (25). We extended these global analyses through direct studies of co-regulated gene clusters delimited by f-retained SBSs. We show that loss of Su(Hw) has limited, if any, effects on expression of these genes in the ovary (Figure 8). Based on these observations, we suggest that the essential ovary function of Su(Hw) may not be related to establishment of boundaries of transcriptional domains, a conclusion supported by recent findings that null and nearly null alleles of mod(mdg4) and Cp190 do not affect oogenesis. We suggest that Su(Hw) may act locally to change gene expression. Recent studies demonstrate that Su(Hw) is associated with repressed chromatin domains (35,57) and is enriched in lamin-associated domains (58). These observations, together with findings that enhancer blocking activity of the gypsy insulator is disrupted by a lamin mutation (59), suggest that Su(Hw)-dependent regulation may involve gene silencing that requires Su(Hw) targeting to the nuclear periphery.

Three classes of SBSs exist with distinct properties

The availability of a high-quality dataset of SBSs provided the opportunity to investigate the genome-wide association of Su(Hw) with its partner proteins, Mod67.2 and CP190. These analyses showed that SBS-O sites represented the largest class (Figure 3). Further, we found that SBS-O and SBS-C sites displayed sequence conservation that extended beyond the Su(Hw)-binding motif, which was not observed for the SBS-CM class. These data suggest that Mod67.2 confers greater flexibility to Su(Hw) association, a postulate supported by our demonstration that Mod67.2 facilitates Su(Hw) occupancy (Figure 4). These findings imply that the structurally related BTB-domain protein CP190 cannot replace the function of Mod67.2 in facilitating Su(Hw) occupancy of SBSs. Although SBSs collectively display no enrichment with genic features, we find a skewed localization of SBS-CM sites to the 5′- and 3′-end of genes and coding exons (Figure 3D). Taken together, these data indicate that different classes of SBSs may have distinct regulatory contributions in the genome.

Effects of loss of a single ZnF on genome-wide binding

Su(Hw) has 12 ZnFs, with ten corresponding to C2H2 fingers and two corresponding to C2HC (7). Previous studies suggest that the major mode for Su(Hw) chromosome association is DNA binding, as loss of ZnF7 causes complete loss of in vivo localization to chromosomes that correlates with defective in vitro binding (23,24). We demonstrated that loss of ZnF10 eliminates Su(Hw)f occupancy at two-thirds of SBSs (Figure 6), with binding site selection of Su(Hw)f showing greater constraints than Su(Hw)+. While Su(Hw)f is lost at many genomic sites, this protein binds f-lost SBSs in vitro, although with reduced affinity relative to Su(Hw)+ (Supplementary Figure S2). Yet, this reduced Su(Hw)f-binding affinity cannot account for all f-lost sites, as there is an absence of a strict correlation between in vitro DNA binding and in vivo chromosome Su(Hw)f occupancy. Further investigation revealed that some SBSs showed tissue-specific Su(Hw)f retention and that Su(Hw)f retention was optimal at SBSs that associate with Mod67.2, a protein partner associated with enhanced occupancy of Su(Hw) (Figure 6). Taken together, these data suggest that Su(Hw)f retention is affected by multiple factors, including DNA sequence, tissue-specific effects that may depend on local chromatin structure and a protein partner of the gypsy insulator complex.

Multi-ZnF domains are the most common DNA-binding motif among transcription factors in metazoan genomes (60). Our data are relevant to understanding how mutation of a single ZnF within a large ZnF-binding domain impacts chromatin occupancy of this class of transcription factors. We show that individual fingers may make distinct contributions to chromosome association, without altering the recognition sequence of the binding site. Interestingly, a second well-characterized vertebrate insulator protein CCCTC-binding factor (CTCF) is an eleven ZnF DNA-binding protein (61–65). Mutations in the gene encoding CTCF have been found in several human tumor samples, including breast, prostate and kidney (66). These tumor-associated alleles carried missense mutations that changed specific CTCF ZnFs, with none producing a truncated protein. Interestingly, in vitro studies demonstrated that these CTCF ZnF mutants had altered in vitro DNA-binding properties, reminiscent of Su(Hw)f. However, no in vivo binding studies were completed. Data obtained from analysis of Su(Hw)f predict that the cancer-associated CTCF mutations may alter the in vivo landscape of CTCF occupancy genome-wide. As a result, these effects may lead to complex changes in gene expression that may promote tumorigenesis.

ACCESSION NUMBER

All ChIP-seq data were submitted to the NIH GEO/Sequence Read Archive database, accession number GSE33052.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR online: Supplementary Figures S1–S3 and Supplementary Tables S1 and S2.

FUNDING

The National Institutes of Health (grant GM42539 to P.K.G., training support T32073610 to R.M.B.); National Science Foundation (grant 0718898 to C.M.H.). Funding for open access charge: National Institutes of Health (grant GM42593 to P.K.G.).

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

We thank the Geyer laboratory for their critical reading of this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Gurudatta BV, Corces VG. Chromatin insulators: lessons from the fly. Brief. Funct. Genomic. Proteomic. 2009;8:276–282. doi: 10.1093/bfgp/elp032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raab JR, Kamakaka RT. Insulators and promoters: closer than we think. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2010;11:439–446. doi: 10.1038/nrg2765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuhn EJ, Geyer PK. Genomic insulators: connecting properties to mechanism. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2003;15:259–265. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(03)00039-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jung CH, Makunin IV, Mattick JS. Identification of conserved Drosophila-specific euchromatin-restricted non-coding sequence motifs. Genomics. 2010;96:154–166. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim TH, Abdullaev ZK, Smith AD, Ching KA, Loukinov DI, Green RD, Zhang MQ, Lobanenkov VV, Ren B. Analysis of the vertebrate insulator protein CTCF-binding sites in the human genome. Cell. 2007;128:1231–1245. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Modolell J, Bender W, Meselson M. Drosophila melanogaster mutations suppressible by the suppressor of Hairy-wing are insertions of a 7.3-kilobase mobile element. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1983;80:1678–1682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.6.1678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parkhurst SM, Harrison DA, Remington MP, Spana C, Kelley RL, Coyne RS, Corces VG. The Drosophila su(Hw) gene, which controls the phenotypic effect of the gypsy transposable element, encodes a putative DNA-binding protein. Genes Dev. 1988;2:1205–1215. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.10.1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spana C, Harrison DA, Corces VG. The Drosophila melanogaster suppressor of Hairy-wing protein binds to specific sequences of the gypsy retrotransposon. Genes Dev. 1988;2:1414–1423. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.11.1414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harrison DA, Geyer PK, Spana C, Corces VG. The gypsy retrotransposon of Drosophila melanogaster: mechanisms of mutagenesis and interaction with the suppressor of Hairy-wing locus. Dev. Genet. 1989;10:239–248. doi: 10.1002/dvg.1020100313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Geyer PK, Green MM, Corces VG. Mutant gene phenotypes mediated by a Drosophila melanogaster retrotransposon require sequences homologous to mammalian enhancers. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1988;85:8593–8597. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.22.8593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parnell TJ, Kuhn EJ, Gilmore BL, Helou C, Wold MS, Geyer PK. Identification of genomic sites that bind the Drosophila suppressor of Hairy-wing insulator protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006;26:5983–5993. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00698-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peifer M, Bender W. Sequences of the gypsy transposon of Drosophila necessary for its effects on adjacent genes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1988;85:9650–9654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.24.9650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geyer PK, Green MM, Corces VG. Reversion of a gypsy-induced mutation at the yellow (y) locus of Drosophila melanogaster is associated with the insertion of a newly defined transposable element. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1988;85:3938–3942. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.11.3938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Scott KC, Taubman AD, Geyer PK. Enhancer blocking by the Drosophila gypsy insulator depends upon insulator anatomy and enhancer strength. Genetics. 1999;153:787–798. doi: 10.1093/genetics/153.2.787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gerasimova TI, Gdula DA, Gerasimov DV, Simonova O, Corces VG. A Drosophila protein that imparts directionality on a chromatin insulator is an enhancer of position-effect variegation. Cell. 1995;82:587–597. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90031-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pai CY, Lei EP, Ghosh D, Corces VG. The centrosomal protein CP190 is a component of the gypsy chromatin insulator. Mol. Cell. 2004;16:737–748. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kurshakova M, Maksimenko O, Golovnin A, Pulina M, Georgieva S, Georgiev P, Krasnov A. Evolutionarily conserved E(y)2/Sus1 protein is essential for the barrier activity of Su(Hw)-dependent insulators in Drosophila. Mol. Cell. 2007;27:332–338. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roseman RR, Johnson EA, Rodesch CK, Bjerke M, Nagoshi RN, Geyer PK. A P element containing suppressor of hairy-wing binding regions has novel properties for mutagenesis in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics. 1995;141:1061–1074. doi: 10.1093/genetics/141.3.1061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Markstein M, Pitsouli C, Villalta C, Celniker SE, Perrimon N. Exploiting position effects and the gypsy retrovirus insulator to engineer precisely expressed transgenes. Nat. Genet. 2008;40:476–483. doi: 10.1038/ng.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.She W, Lin W, Zhu Y, Chen Y, Jin W, Yang Y, Han N, Bian H, Zhu M, Wang J. The gypsy insulator of Drosophila melanogaster, together with its binding protein suppressor of Hairy-wing, facilitate high and precise expression of transgenes in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genetics. 2010;185:1141–1150. doi: 10.1534/genetics.110.117960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harrison DA, Gdula DA, Coyne RS, Corces VG. A leucine zipper domain of the suppressor of Hairy-wing protein mediates its repressive effect on enhancer function. Genes Dev. 1993;7:1966–1978. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.10.1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klug WS, Bodenstein D, King RC. Oogenesis in the suppressor of hairy-wing mutant of Drosophila melanogaster. I. Phenotypic characterization and transplantation experiments. J. Exp. Zool. 1968;167:151–156. doi: 10.1002/jez.1401670203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim J, Shen B, Rosen C, Dorsett D. The DNA-binding and enhancer-blocking domains of the Drosophila suppressor of Hairy-wing protein. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1996;16:3381–3392. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.7.3381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuhn-Parnell EJ, Helou C, Marion DJ, Gilmore BL, Parnell TJ, Wold MS, Geyer PK. Investigation of the properties of non-gypsy suppressor of hairy-wing-binding sites. Genetics. 2008;179:1263–1273. doi: 10.1534/genetics.108.087254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baxley RM, Soshnev AA, Koryakov DE, Zhimulev IF, Geyer PK. The role of the Suppressor of Hairy-wing insulator protein in Drosophila oogenesis. Dev. Biol. 2011;356:398–410. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.05.666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Langmead B. Aligning short sequencing reads with Bowtie. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics. 2010;32:11.7.1–11.7.14. doi: 10.1002/0471250953.bi1107s32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bailey TL, Elkan C. Fitting a mixture model by expectation maximization to discover motifs in biopolymers. Proc. Int. Conf. Intell Syst. Mol. Biol. 1994;2:28–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Crooks GE, Hon G, Chandonia JM, Brenner SE. WebLogo: a sequence logo generator. Genome Res. 2004;14:1188–1190. doi: 10.1101/gr.849004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schneider TD, Stephens RM. Sequence logos: a new way to display consensus sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:6097–6100. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.20.6097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stormo GD, Fields DS. Specificity, free energy and information content in protein-DNA interactions. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1998;23:109–113. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(98)01187-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hertz GZ, Stormo GD. Identifying DNA and protein patterns with statistically significant alignments of multiple sequences. Bioinformatics. 1999;15:563–577. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/15.7.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim C, Paulus BF, Wold MS. Interactions of human replication protein A with oligonucleotides. Biochemistry. 1994;33:14197–14206. doi: 10.1021/bi00251a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bushey AM, Ramos E, Corces VG. Three subclasses of a Drosophila insulator show distinct and cell type-specific genomic distributions. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1338–1350. doi: 10.1101/gad.1798209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nègre N, Brown CD, Shah PK, Kheradpour P, Morrison CA, Henikoff JG, Feng X, Ahmad K, Russell S, White RA, et al. A comprehensive map of insulator elements for the Drosophila genome. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000814. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kharchenko PV, Alekseyenko AA, Schwartz YB, Minoda A, Riddle NC, Ernst J, Sabo PJ, Larschan E, Gorchakov AA, Gu T, et al. Comprehensive analysis of the chromatin landscape in Drosophila melanogaster. Nature. 2011;471:480–485. doi: 10.1038/nature09725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Geyer PK. The role of insulator elements in defining domains of gene expression. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 1997;7:242–248. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(97)80134-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Srinivasan S, Dorighi KM, Tamkun JW. Drosophila Kismet regulates histone H3 lysine 27 methylation and early elongation by RNA polymerase II. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000217. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Armstrong JA, Papoulas O, Daubresse G, Sperling AS, Lis JT, Scott MP, Tamkun JW. The Drosophila BRM complex facilitates global transcription by RNA polymerase II. EMBO J. 2002;21:5245–5254. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morettini S, Tribus M, Zeilner A, Sebald J, Campo-Fernandez B, Scheran G, Wörle H, Podhraski V, Fyodorov DV, Lusser A. The chromodomains of CHD1 are critical for enzymatic activity but less important for chromatin localization. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:3103–3115. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Regnard C, Straub T, Mitterweger A, Dahlsveen IK, Fabian V, Becker PB. Global analysis of the relationship between JIL-1 kinase and transcription. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1001327. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Longworth MS, Herr A, Ji JY, Dyson NJ. RBF1 promotes chromatin condensation through a conserved interaction with the Condensin II protein dCAP-D3. Genes Dev. 2008;22:1011–1024. doi: 10.1101/gad.1631508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ghosh D, Gerasimova TI, Corces VG. Interactions between the Su(Hw) and Mod(mdg4) proteins required for gypsy insulator function. EMBO J. 2001;20:2518–2527. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.10.2518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wallace HA, Plata MP, Kang HJ, Ross M, Labrador M. Chromatin insulators specifically associate with different levels of higher-order chromatin organization in Drosophila. Chromosoma. 2010;119:177–194. doi: 10.1007/s00412-009-0246-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bartkuhn M, Straub T, Herold M, Herrmann M, Rathke C, Saumweber H, Gilfillan GD, Becker PB, Renkawitz R. Active promoters and insulators are marked by the centrosomal protein 190. EMBO J. 2009;28:877–888. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yang J, Corces VG. Chromatin insulators: a role in nuclear organization and gene expression. Adv. Cancer Res. 2011;110:43–76. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-386469-7.00003-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gerasimova TI, Lei EP, Bushey AM, Corces VG. Coordinated Control of dCTCF and gypsy Chromatin Insulators in Drosophila. Mol. Cell. 2007;28:761–772. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.09.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gause M, Morcillo P, Dorsett D. Insulation of enhancer-promoter communication by a gypsy transposon insert in the Drosophila cut gene: cooperation between suppressor of hairy-wing and modifier of mdg4 proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001;21:4807–4817. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.14.4807-4817.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Adryan B, Woerfel G, Birch-Machin I, Gao S, Quick M, Meadows L, Russell S, White R. Genomic mapping of Suppressor of Hairy-wing binding sites in Drosophila. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R167. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-8-r167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Spellman PT, Rubin GM. Evidence for large domains of similarly expressed genes in the Drosophila genome. J. Biol. 2002;1:5. doi: 10.1186/1475-4924-1-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boutanaev AM, Kalmykova AI, Shevelyov YY, Nurminsky DI. Large clusters of co-expressed genes in the Drosophila genome. Nature. 2002;420:666–669. doi: 10.1038/nature01216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weber CC, Hurst LD. Support for multiple classes of local expression clusters in Drosophila melanogaster, but no evidence for gene order conservation. Genome Biol. 2011;12:R23. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-3-r23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dorus S, Busby SA, Gerike U, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Karr TL. Genomic and functional evolution of the Drosophila melanogaster sperm proteome. Nat. Genet. 2006;38:1440–1445. doi: 10.1038/ng1915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chintapalli VR, Wang J, Dow JA. Using FlyAtlas to identify better Drosophila melanogaster models of human disease. Nat. Genet. 2007;39:715–720. doi: 10.1038/ng2049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Meister P, Mango SE, Gasser SM. Locking the genome: nuclear organization and cell fate. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2011;21:167–174. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2011.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Soshnev AA, Li X, Wehling MD, Geyer PK. Context differences reveal insulator and activator functions of a Su(Hw) binding region. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000159. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wood AM, Van Bortle K, Ramos E, Takenaka N, Rohrbaugh M, Jones BC, Jones KC, Corces VG. Regulation of chromatin organization and inducible gene expression by a Drosophila insulator. Mol. Cell. 2011;44:29–38. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.07.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Filion GJ, van Bemmel JG, Braunschweig U, Talhout W, Kind J, Ward LD, Brugman W, de Castro IJ, Kerkhoven RM, Bussemaker HJ, et al. Systematic protein location mapping reveals five principal chromatin types in Drosophila cells. Cell. 2010;143:212–224. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.van Bemmel JG, Pagie L, Braunschweig U, Brugman W, Meuleman W, Kerkhoven RM, van Steensel B. The insulator protein SU(HW) fine-tunes nuclear lamina interactions of the Drosophila genome. PLoS One. 2010;5:e15013. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0015013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Capelson M, Corces VG. The ubiquitin ligase dTopors directs the nuclear organization of a chromatin insulator. Mol. Cell. 2005;20:105–116. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.08.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Klug A. The discovery of zinc fingers and their applications in gene regulation and genome manipulation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2010;79:213–231. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-010909-095056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ohlsson R, Lobanenkov V, Klenova E. Does CTCF mediate between nuclear organization and gene expression? Bioessays. 2010;32:37–50. doi: 10.1002/bies.200900118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nativio R, Sparago A, Ito Y, Weksberg R, Riccio A, Murrell A. Disruption of genomic neighbourhood at the imprinted IGF2-H19 locus in Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome and Silver-Russell syndrome. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2011;20:1363–1374. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nikolaev LG, Akopov SB, Didych DA, Sverdlov ED. Vertebrate protein CTCF and its multiple roles in a large-scale regulation of genome activity. Curr. Genomics. 2009;10:294–302. doi: 10.2174/138920209788921038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Phillips JE, Corces VG. CTCF: master weaver of the genome. Cell. 2009;137:1194–1211. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wallace JA, Felsenfeld G. We gather together: insulators and genome organization. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2007;17:400–407. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2007.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Filippova GN, Qi CF, Ulmer JE, Moore JM, Ward MD, Hu YJ, Loukinov DI, Pugacheva EM, Klenova EM, Grundy PE, et al. Tumor-associated zinc finger mutations in the CTCF transcription factor selectively alter tts DNA-binding specificity. Cancer Res. 2002;62:48–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.