Abstract

A central function of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is to coordinate protein biosynthetic and secretory activities in the cell. Alterations in ER homeostasis cause accumulation of misfolded/unfolded proteins in the ER. To maintain ER homeostasis, eukaryotic cells have evolved the unfolded protein response (UPR), an essential adaptive intracellular signaling pathway that responds to metabolic, oxidative stress, and inflammatory response pathways. The UPR has been implicated in a variety of diseases including metabolic disease, neurodegenerative disease, inflammatory disease, and cancer. Signaling components of the UPR are emerging as potential targets for intervention and treatment of human disease.

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and ER stress

The ER is a vital organelle for production of secretory proteins that are synthesized by ER-bound ribosomes and then modified and folded by a machinery of foldases and molecular chaperones in the ER lumen. Correctly folded secretory proteins exit the ER en route to other intracellular organelles and the extracellular surface. The rates of protein synthesis, folding, and trafficking are precisely coordinated by an efficient system termed “quality control” to ensure that only properly folded proteins exit the ER. Misfolded proteins are either retained within the ER or subject to degradation by the proteasome-dependent ER-associated protein degradation (ERAD) pathway or by autophagy. Many diseases result from protein misfolding caused by gene mutations that disrupt protein-folding pathways.

The ER is the major site for the synthesis of sterols and phospholipids that constitute the bulk of the lipid components of all biological membranes. The ER, therefore, plays an essential role in controlling the lipid composition in membranes, which, in turn, determines the biophysical properties and functions of cell membranes (Fagone and Jackowski, 2009). ER membrane expansion generally reflects the increased secretory capacity of the cell. Lipid homeostasis in membranes maintained by the ER is important for normal functions of secretory cells (Leonardi et al., 2009).

The ER is also the main site for storage of intracellular Ca2+. The concentration of Ca2+ in the ER lumen can reach ∼5 mM (Stutzmann and Mattson, 2011). The majority of ER-luminal Ca2+ is bound to ER molecular chaperones and is required for their optimal function. In addition, ER Ca2+ release is sensed by mitochondria as either survival or apoptotic signals in the cell. Deregulation of the ER Ca2+ content is reported in a number of diseases including Alzheimer’s disease, Huntington’s disease, and polycystic kidney disease (Sammels et al., 2010).

The ER is a highly dynamic organelle and responds to environmental stress and developmental cues through a series of signaling cascades known as the unfolded protein response (UPR; Schröder and Kaufman, 2005). The primary signal that activates the UPR is the accumulation of misfolded proteins in the ER lumen (Dorner et al., 1989). As a consequence, the UPR regulates the size, the shape (Schuck et al., 2009), and the components of the ER to accommodate fluctuating demands on protein folding, as well as other ER functions in coordination with different physiological and pathological conditions. Recent studies on the integration of ER stress signaling pathways with metabolic stress, oxidative stress, and inflammatory response signaling pathways highlight new insights into the diverse cellular processes that are regulated by the UPR (Hotamisligil, 2010). The accessibility to genetically engineered model organisms has further advanced our understanding of the physiological and pathological impacts of the UPR in human physiology and disease. Here, we summarize the adaptive and apoptotic pathways mediated by the UPR and discuss how the UPR responds in different physiological and pathological states.

The adaptive role of the mammalian UPR

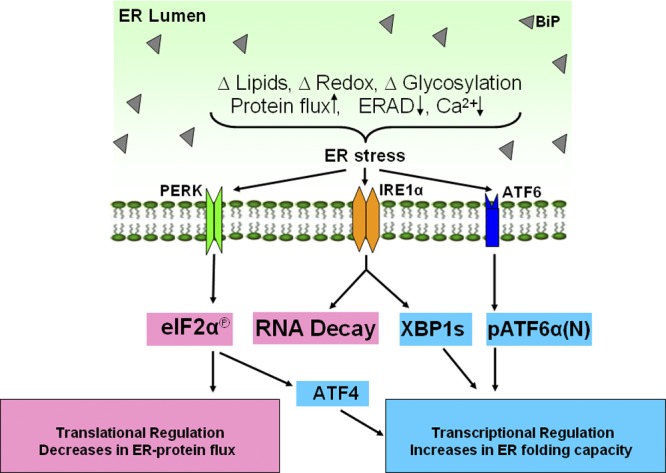

In mammals, three ER membrane-associated proteins act as ER stress sensors (Fig. 1): (1) the inositol-requiring transmembrane kinase/endoribonuclease 1 (IRE1); (2) the double-stranded RNA (PKR)–activated protein kinase-like eukaryotic initiation factor 2α kinase (PERK); and (3) the activating transcription factor-6 (ATF6). Each UPR sensor binds to the ER luminal chaperone BiP. When misfolded proteins accumulate in the ER, they bind to and sequester BiP, thereby activating the sensors (Bertolotti et al., 2000; Ma et al., 2002; Shen et al., 2002). However, additional mechanisms that initiate and modulate the activity of individual UPR branches have been reported, in particular for IRE1 (Gardner and Walter, 2011; Promlek et al., 2011), which may explain their diverse responses to different signals and/or in different cell types.

Figure 1.

ER stress and the unfolded protein response. A number of conditions such as disturbed lipid homeostasis, disturbed calcium signaling, oxidative stress, inhibition of glycosylation, increased protein synthesis, and decreased ER-associated degradation can cause ER stress and activate the unfolded protein response (UPR). The UPR is mediated by three ER membrane-associated proteins, PERK, IRE1α, and ATF6α, to induce translational and transcriptional changes upon ER stress. PERK phosphorylates eIF2α to attenuate general protein translation and decrease protein efflux into the ER. Phosphorylated eIF2α also selectively stimulates ATF4 translation to induce transcriptional regulation of UPR genes. IRE1α cleaves XBP1 mRNA to a spliced form of XBP1 that translates XBP1s to up-regulate UPR genes encoding factors involved in ER protein folding and degradation. ATF6α traffics to Golgi for cleavage by S1P and S2P to release pATF6α(N) that works synergistically or separately with XBP1s to regulate UPR gene expression.

IRE1 is the most conserved branch of the UPR, present from yeast to humans. Mammalian IRE1 has two homologues, IRE1α and IRE1β. IRE1α is expressed in all cells and tissues, whereas IRE1β is specifically expressed in the intestinal epithelium. UPR signaling is mainly mediated through IRE1α, and the function of IRE1β in the UPR is still not clear. Activated IRE1α cleaves a 26-base fragment from the mRNA encoding the X-box binding protein-1 (XBP1; Yoshida et al., 2001). Spliced Xbp1 mRNA is translated into a potent transcription factor, XBP1s, which targets a wide variety of genes encoding proteins involved in ER membrane biogenesis, ER protein folding, ERAD, and protein secretion from the cell (Lee et al., 2003; Acosta-Alvear et al., 2007). Mouse genetic studies showed that germline deletion of Xbp1 or Ire1α in mice is embryonic lethal (Reimold et al., 2000; Zhang et al., 2005). Recently, a role for IRE1α was suggested in the placenta for oxygen/nutrient exchange between the maternal and fetal circulation (Iwawaki et al., 2009). However, the contribution of XBP1 in the IRE1α pathway to placental development has not been addressed. A recent study identified an inhibitor of IRE1α endoribonuclease activity that did not alter the cellular response to ER stress, but did reduce ER expansion in an exocrine cell model of differentiation. This result suggests that IRE1α may play a more significant role in ER expansion associated with differentiation of secretory cell types than with the adaptation to ER stress (Kaufman et al., 2002; Cross et al., 2012).

PERK is the second arm of the mammalian UPR and is structurally related to IRE1α, with an ER luminal dimerization domain and a cytosolic kinase domain. The immediate effect of PERK activation is the phosphorylation of the α subunit of eukaryotic translational initiation factor 2α (eIF2α) at Ser51 that attenuates global protein synthesis to decrease protein influx into the ER lumen (Shi et al., 1998; Harding et al., 2000b; Scheuner et al., 2001). On the other hand, phosphorylation of eIF2α can change the efficiency of AUG initiation codon utilization (Kaufman, 2004), leading to, for example, preferential translation of activating transcription factor-4 (ATF4) protein over other upstream reading frames in the mRNA (Harding et al., 2000a). ATF4 is a transcription factor that induces expression of genes involved in ER function, as well as ER stress–induced apoptosis, ER stress–mediated production of reactive oxygen species, and an inhibitory feedback loop through dephosphorylation of eIF2α to prevent hyperactivation of the UPR (Harding et al., 2003). PERK was also reported to phosphorylate nuclear erythroid 2 p45-related factor 2 (NRF2) to induce antioxidant response genes including heme oxygenase 1 and glutathione S-transferase (Cullinan et al., 2003). Therefore, the PERK–eIF2α arm of the UPR acts to preserve redox balance during ER stress through activation of ATF4 and NRF2.

ATF6α is the third arm of the mammalian UPR that is an ER-associated type 2 transmembrane basic leucine zipper (bZIP) transcription factor. ATF6β is a distant homologue of ATF6α but both are ubiquitously expressed in all tissues. Upon release from BiP, ATF6α traffics to the Golgi apparatus for cleavage by serine protease site-1 (S1P) and metalloprotease site-2 (S2P) to release the transcription-activating form of ATF6, pATF6α(N) (Schindler and Schekman, 2009). The pATF6α(N) can act independently or synergistically with XBP1s for induction of UPR target genes. The role of pATF6α(N) in development is apparently minimal because mice lacking ATF6α are viable without significant abnormalities, although ATF6α-null mice are exquisitely sensitive to ER stress (Wu et al., 2007; Yamamoto et al., 2010). Although there has not been a phenotype associated with ATF6β deletion, mice lacking both ATF6α and ATF6β are embryonic lethal, suggesting they display functional redundancy in early development (Yamamoto et al., 2007). Thus, the common role(s) for ATF6α and ATF6β in development needs to be clarified.

In addition to the core components of the UPR, mammals have also evolved some tissue-specific UPR sensors, most of which are transmembrane bZIP transcription factors that are activated by regulated intramembrane proteolysis in a similar manner to ATF6. To date, several of these proteins including cAMP responsive element-binding protein H (CREBH or CREB3L3), CREB3 (Luman), CREB3L1 (Oasis), CREB3L2 (BBF2H7), and CREB4 (Tisp40) have been identified in response to conventional ER stress inducers (Bailey and O’Hare, 2007). Although the exact mechanisms of their activation are not fully understood, it appears that they synergize with the mainstream UPR to expand and/or enhance the diversity of UPR signaling and fine-tune the ER stress response in a temporal and/or cell type–specific manner (Zhang et al., 2006).

The apoptotic role of the mammalian UPR

Chronic or severe ER stress activates the UPR leading to apoptotic death. Most data support the notion that PERK–eIF2α–ATF4 signaling is a primary determinant for apoptosis (Rutkowski et al., 2006). Persistent and/or severe ER stress leads to activation of the PERK–eIF2α–ATF4 pathway and culminates in the induction of the CCAAT enhancer-binding protein (C/EBP) homologous protein (CHOP/GADD153), a proapoptotic factor induced by ER stress (Zinszner et al., 1998). CHOP up-regulates apoptosis-related genes including DR5 (Yamaguchi and Wang, 2004), Trb3 (Ohoka et al., 2005), BIM (Puthalakath et al., 2007), and PUMA (Cazanave et al., 2010) to promote cell death during ER stress. Importantly, CHOP also induces GADD34, a regulatory subunit of protein phosphatase I to dephosphorylate eIF2α and reverse attenuation of mRNA translation. The cytotoxic effects of CHOP are at least in part through GADD34 because CHOP and GADD34 knockout animals are protected from ER stress–induced tissue damage (Marciniak et al., 2004; Malhotra et al., 2008; Song et al., 2008). In addition, selective inhibitors of eIF2α dephosphorylation that target GADD34 can rescue cells from protein misfolding stress (Boyce et al., 2005; Tsaytler et al., 2011). How does translation attenuation divert cells from a cell death pathway to survival during ER stress? One hypothesis is that translation attenuation prevents continued synthesis of unfolded proteins that would exacerbate protein-misfolding stress in the ER leading to a death response.

Under severe stress, activation of IRE1α was implicated in cell death mediated by apoptosis signaling kinase 1 (ASK1) through their interaction with tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated factor 2 (TRAF2; Nishitoh et al., 2002). It was also reported that IRE1α indiscriminately degrades ER-localized mRNAs that can lead to cell death (Hollien et al., 2009; Vecchi et al., 2009). However, the pro-apoptotic signaling molecule(s) that targets activation of this indiscriminate RNase activity of IRE1α has not been identified.

The UPR in health and disease

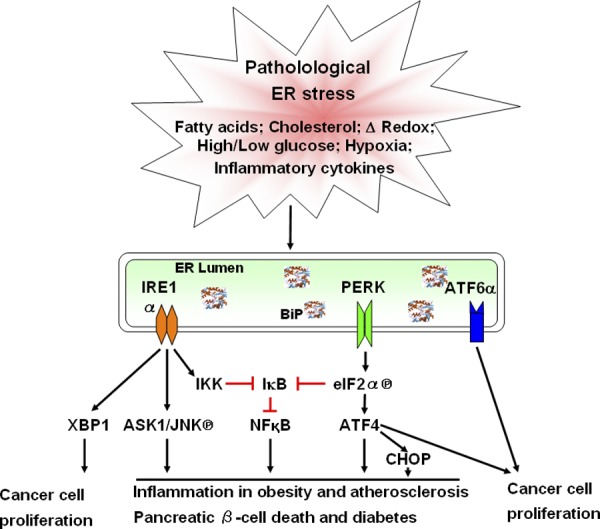

Many extracellular stimuli and fluctuations in intracellular homeostasis disrupt protein folding in the ER. As a consequence, the cell uses its ER protein-folding status as an exquisite sensor to monitor intracellular homeostasis. Pharmacological insults were initially used to elucidate how cells cope with immediate and severe challenges to the protein-folding quality control system. It is now evident that intracellular signaling, such as insulin anabolic responses, as well as metabolic conditions including hyperlipidemia, hyperhomocysteinemia, hyperglycemia, and inflammatory cytokines all disrupt protein folding in the ER. As a consequence, UPR activation is observed in many human diseases and mouse models of human disease. Therefore, it was proposed that ER stress contributes to the pathology of many human diseases (Kaufman, 2002). Cell death, a physiological consequence of chronic ER stress, is a key to the pathogenesis of many diseases including metabolic disease, inflammation, neurodegenerative disorders, and cancer (Fig. 2). Here, we describe how the use of animal models has contributed to our knowledge of how the UPR impacts cellular homeostasis, normal physiology, and disease pathogenesis.

Figure 2.

UPR signaling in diseases. Pathophysiological conditions such as hypoxia, elevated levels of fatty acids or cholesterol, oxidative stress, high or low glucose levels, and inflammatory cytokines induce ER stress and activate the UPR chronically. UPR signaling is interconnected with oxidative stress and inflammatory response pathways and involved in a variety of diseases including metabolic disease, inflammatory disease, and cancer. The three arms of the UPR, IRE1α-XBP1s, PERK-eIF2α phosphorylation-ATF4, and ATF6 are important for tumor cell survival and growth under hypoxic conditions. The UPR, IRE1α, and PERK can activate c-JUN N-terminal kinase (JNK) and NFκB to promote inflammation and apoptosis that contribute to inflammation in obesity and pancreatic β-cell death in diabetes. In addition, CHOP production in the PERK pathway exacerbates oxidative stress in diabetic states and atherosclerosis to aggravate the diseases.

The UPR in diabetes

Cells that are stimulated to secrete large amounts of protein over a short period of time are highly dependent on a functional UPR. Upon glucose stimulation, the pancreatic β cell increases proinsulin synthesis up to 10-fold (Itoh et al., 1978). The PERK–eIF2α arm of the UPR is indispensable for β cells to adapt to large fluctuations in proinsulin synthesis (Harding et al., 2000b; Scheuner et al., 2001). This is most evident from characterization of Wolcott-Rallison syndrome in which individuals require insulin at the age of three years. This autosomal recessive disease is due to loss-of-function mutations in PERK that cause β cell failure. Similarly, whole body inactivation of the PERK signaling pathway in mice causes a defect in β cell expansion during neonatal development and hyperglycemia with reduced serum insulin levels (Harding et al., 2000b; Scheuner et al., 2001). Conditional deletion of Perk in β cells further supports a homeostatic role for PERK signaling in β cell survival (Cavener et al., 2010). Consistent with these observations, mice with a Ser51Ala mutation at the PERK phosphorylation site in eIF2α in a homozygous state, or in a heterozygous state combined with stress of a high fat diet, display β cell loss due to proinsulin misfolding, ER stress, oxidative stress, and apoptosis (Scheuner et al., 2005). In addition, increased protein synthesis in β cells by removing eIF2α phosphorylation caused a reduction in insulin production, which was due to ER dysfunction, oxidative stress, and loss of β cells. Strikingly, feeding an antioxidant diet prevented the β cell failure upon increased proinsulin synthesis (Back et al., 2009). These findings demonstrate that translational control of proinsulin through phosphorylation of eIF2α is required to coordinate proinsulin synthesis with proinsulin folding to maintain β cell homeostasis. Importantly, an increase in proinsulin synthesis alone is sufficient to initiate a series of events including proinsulin misfolding, insulin granule depletion, loss of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion, and oxidative stress, similar to those observed in type II diabetes (Huang et al., 2007; Laybutt et al., 2007).

Recent genetic evidence indicates that proapoptotic components of the ER stress response exacerbate β cell failure in type II diabetes. Deletion of Chop improved glucose control and increased β cell mass in heterozygous diabetic Akita mice that express a misfolding-prone Cys96Tyr proinsulin (Oyadomari et al., 2002). Furthermore, Chop deletion improved β cell function in several mouse models of type II diabetes: (a) high fat diet-fed heterozygous Ser51Ala eIF2α mice; (b) mice fed a high fat diet and then given streptozotocin, a compound that kills β cells and induces diabetes; and (c) leptin receptor–null (db/db) mice. Chop deletion not only protected β cells from apoptosis, but also improved β cell function by reducing oxidative damage and improving protein folding in the ER (Song et al., 2008).

XBP1 is also required for insulin maturation and secretion. Xbp1 deletion in β cells markedly impaired proinsulin processing and decreased insulin production (A.H. Lee et al., 2011). Enforced expression of XBP1s, as well as ATF6α, inhibited insulin expression and ultimately killed β cells, indicating the importance of homeostatic control of UPR signaling in β cells (Allagnat et al., 2010). Although a mouse model with β cell deletion in Ire1α has not been reported, it is also likely required for insulin production, similar to XBP1. However, it was proposed that activated IRE1α degrades proinsulin mRNA to inhibit insulin production (Lipson et al., 2006; Han et al., 2009). The significance of this IRE1α-mediated proinsulin mRNA degradation needs to be confirmed in a physiological setting.

Wolfram syndrome, a rare genetic disorder, provides another link between ER stress, β cell death, and diabetes. Recent genome-wide association studies showed that polymorphisms in WFS1 are associated with impaired β cell function and risk for type II diabetes (Franks et al., 2008). WFS1, a downstream transcriptional target of XBP1, encodes an ER transmembrane protein that negatively regulates ATF6α to prevent β cell death as a consequence of prolonged ATF6α activation (Fonseca et al., 2010). There are reports of ATF6α variants associated with type II diabetes (Thameem et al., 2006; Chu et al., 2007; Meex et al., 2007), suggesting ATF6α might also play a role in β cell function, consistent with recent findings that suggest ATF6α protects β cells from ER stress (Usui et al., 2012).

The UPR in metabolic syndrome

The identification of genetic and environmental factors involved in metabolic syndrome have revealed that ER stress can intensify a variety of inflammatory and stress signaling pathways to aggravate metabolic derangement, leading to obesity, insulin resistance, fatty liver, and dyslipidemia (Fu et al., 2012). In addition to β cells, hepatocytes and adipocytes also significantly contribute to glucose and lipid homeostasis in the body.

ER stress is linked with hepatic steatosis, which is due to either enhanced lipogenesis or decreased hepatic lipoprotein secretion. Overexpression of the protein chaperone BiP in the liver, as what may occur upon activation of the UPR, inhibited activation of the central lipogenic regulator-sterol regulatory element binding protein (SREBP-1c), alleviated hepatic steatosis, and improved glucose homeostatic control in obese mice (Kammoun et al., 2009). ER stress also inhibits hepatic lipoprotein secretion (Ota et al., 2008). Although disruption of any single arm of the UPR aggravated steatosis under pharmacologically induced ER stress, it is not known whether this resulted from increased hepatic lipogenesis or decreased lipoprotein secretion (Rutkowski et al., 2008; Zhang et al., 2011). XBP1s also regulates fatty acid synthesis by inducing expression of critical lipogenic enzymes, including stearoyl-CoA desaturase-1 (Lee et al., 2008). Interestingly, XBP1s interacts with the Forkhead box O1 (FoxO1) transcription factor and the regulatory subunits of PI3K, p85α, and p85β to decrease hepatic gluconeogenesis (Park et al., 2010; Zhou et al., 2011). However, only hypolipidemia, but neither hypoglycemia nor hyperglycemia, was observed in Xbp1 liver-deleted mice, suggesting that the regulatory role of XBP1 in hepatic metabolism is primarily to maintain lipid, and not glucose, homeostasis.

CREBH, a liver-specific component of the UPR, was originally identified as a central regulator of the acute phase response, a finding that first linked ER stress with innate systemic inflammatory responses (Zhang et al., 2006). Although it was recognized that metabolic control and inflammation were intimately connected (Reddy and Rao, 2006), a mechanism was lacking. As part of a transducer of inflammatory responses in the liver, CREBH was recently demonstrated to also regulate hepatic lipogenesis, fatty acid oxidation, and lipolysis under conditions of metabolic stress (Zhang et al., 2012). In addition, CREBH regulates hepatic VLDL-triglyceride clearance in the plasma by controlling the activity of lipoprotein lipase (Lpl) through up-regulating genes encoding Lpl coactivator apolipoproteins C2, A4, and A5, respectively, and down-regulating the Lpl inhibitor Apoc3 (J.H. Lee et al., 2011). The identification of CREBH as a stress-inducible metabolic regulator is likely significant because multiple nonsynonymous mutations in CREBH produce defective CREBH proteins that were reported in humans with extreme hypertriglyceridemia (J.H. Lee et al., 2011). These findings indicate that CREBH is a molecular link between lipid homeostasis and inflammation. Although CREBH interacts with ATF6α (Zhang et al., 2006), data indicate that they exert opposite effects on gluconeogenesis. ATF6α inhibits hepatic glucose output by competing with CREB for interaction with CRTC2 (Wang et al., 2009), while CREBH promotes gluconeogenic activity in a CRTC2-independent manner via an unknown mechanism (Lee et al., 2010). In obese (ob/ob, db/db) mice, elevated gluconeogenesis was at least in part attributed to decreased levels of ATF6α resulting from chronic ER stress in obese livers (Wang et al., 2009).

Adipocyte differentiation is a crucial step in body weight gain. UPR activation including eIF2α phosphorylation and splicing of Xbp1 mRNA was detected during adipogenesis. In addition, attenuation of ER stress by treatment with the chemical chaperone 4-phenylbutyrate (4-PBA) inhibits adipogenesis (Basseri et al., 2009). Thus, the ER stress–induced UPR appears to be a stimulus for adipogenesis that requires the IRE1α–XBP1 pathway to enhance the expression of the key adipogenic factor C/EBPα (Sha et al., 2009). On the other hand, CHOP inhibits adipogenesis by interfering with C/EBPα action (Batchvarova et al., 1995). Therefore, the two arms of the UPR apparently exert opposite effects on adipogenesis, raising the question as to how the UPR coordinates adipocyte differentiation in vivo. Further studies are required to address this issue.

Accumulating evidence indicates that ER stress contributes to the development of insulin resistance in obesity. Treatment of obese and diabetic mice with the chemical chaperones PBA or taurine-conjugated ursodeoxycholic acid (TUDCA) alleviated ER stress–induced activation of c-JUN N-terminal kinase, corrected hyperglycemia, and improved systemic insulin sensitivity (Ozcan et al., 2006). PBA treatment also improved glucose tolerance in insulin-resistant humans (Xiao et al., 2011) and TUDCA improved insulin sensitivity in liver and muscle, but not adipose tissue, in obese men and women (Kars et al., 2010). Heterozygous Xbp1-deleted mice develop advanced diet-induced insulin resistance due to unresolved ER stress coupled with a compromised UPR (Ozcan et al., 2006). In contrast, BiP heterozygosity attenuated diet-induced obesity and insulin resistance associated with an activated UPR (R. Ye et al., 2010). However, deletion of BiP in the liver is extremely toxic, creating tremendous ER stress and hyperactivation of the UPR (Ji et al., 2011). Therefore, the UPR may be a binary switch between beneficial and detrimental effects to maintain metabolic homeostasis.

The UPR in infectious and inflammatory disease

The role of the UPR in viral infection was well studied in the last decade. Viruses that express high levels of glycoproteins activate IRE1α and PERK. PERK-mediated eIF2α phosphorylation is a frontline defense to viral replication in the host through repressing viral protein synthesis (Cheng et al., 2005). The role of XBP1s in the immune response was first recognized as its description as an essential transcription factor for the differentiation of mature B cells to plasma cells, where XBP1s expands the ER to support a large amount of immunoglobulin synthesis (Reimold et al., 2001). Interestingly, activation of IRE1α was required not only for B cell differentiation, but also for B lymphopoiesis in the early stages, suggesting IRE1α serves additional functions other than splicing XBP1s early in B cell lymphopoiesis (Zhang et al., 2005). Recently, XBP1 was shown to play a protective role in inflammatory bowel disease. Deletion of Xbp1 compromised ER protein folding capacity to impair antimicrobial peptide production and elevated mucosal inflammatory signals in the intestine (Kaser et al., 2008). In addition, hypomorphic variants of XBP1 are associated with ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease in humans (Kaser et al., 2008), suggesting the significance of UPR activation in intestinal epithelial cells. Presently, this is an intense area of investigation (Kaser et al., 2011).

The UPR is also involved in innate immune responses. Toll-like receptor (TLR) 4 and TLR2 specifically trigger phosphorylation of IRE1α leading to splicing of Xbp1 mRNA (Iwakoshi et al., 2007). This TLR-dependent Xbp1 mRNA splicing is required for maximal production of proinflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin 6 in macrophages (Martinon et al., 2010). In contrast, TLR signaling inhibits ATF6α and PERK activity as well as signaling through ATF4 and CHOP in macrophages (Woo et al., 2009). Another pathogenic effect of chronic ER stress on activation of inflammatory pathways in macrophages is the progression of atherosclerosis in the settings of dyslipidemia. Deletion of Chop lessened advanced lesion macrophage apoptosis and plaque necrosis in both the Ldlr−/− and ApoE−/− models of atherosclerosis (Thorp et al., 2009). However, the effect of TLR-dependent Xbp1 mRNA splicing on the progression of atherosclerosis requires further investigation.

The UPR in cancer

The UPR is required for tumor cell growth in a hypoxic environment. Inactivation of the PERK pathway by either generating mutations in the kinase domain of PERK or introducing a phosphorylation-resistant form of eIF2α impairs cell survival under extreme hypoxia (Fels and Koumenis, 2006). PERK also promotes cancer cell proliferation and tumor growth by limiting oxidative DNA damage through ATF4 (Bobrovnikova-Marjon et al., 2010). Thus, PERK–phospho-eIF2α–ATF4 signaling is critical for tumor cell proliferation and tumor growth (J. Ye et al., 2010). Although a fusion protein of CHOP, the downstream target of ATF4, with an RNA-binding domain was found in all cases of an adipose cell–based tumor (myxoid liposarcoma; Crozat et al., 1993), the function of CHOP in tumorigenesis remains unknown.

The IRE1α–XBP1 axis of the UPR is also important for tumor cell survival and growth under hypoxic conditions. In a mouse glioma model, IRE1α inhibition decreased tumor growth and reduced angiogenesis and blood perfusion, which correlated with increased overall survival in glioma-implanted recipient mice (Auf et al., 2010). Deletion of Xbp1 increased sensitivity to hypoxia-induced cell death and reduced tumor formation (Fujimoto et al., 2007). IRE1α–XBP1 transcriptional induction of proangiogenic factors, such as vascular endothelial growth factor, was suggested to promote tumorigenesis (Ghosh et al., 2010). Inhibiting the IRE1α–XBP1 axis may be a promising approach for anticancer therapy (Koong et al., 2006). Treatment with STF-083010, a selective inhibitor of the IRE1α RNase activity, demonstrated significant antimyeloma activity in human multiple myeloma xenografts (Papandreou et al., 2011). MKC-3946, another small molecule that inhibits IRE1α-mediated XBP1 splicing, was also reported to strongly suppress multiple myeloma cell growth in vivo (Mimura et al., 2012). In addition, ATF6α plays a pivotal survival role for dormant tumor cells through activation of mTOR signaling (Schewe and Aguirre-Ghiso, 2008). Increased expression of BiP/GRP78, which is primarily regulated by ATF6α, correlates with chemotherapeutic resistance and is observed in aggressive cancers (Lee, 2007).

Most significantly, the success of proteasome inhibition with bortezomib in multiple myeloma (Dimopoulos et al., 2011) supports the notion that targeting protein homeostasis may be therapeutic in a number of cancers that are associated with excessive expression of secretory proteins, such as epithelial tumors. Because the UPR is highly activated in cancer cells, chemotherapeutic agents that cause ER stress such as brefeldin A, bortezomib (Velcade), and geldanamycin could be effective by exacerbating UPR activation to activate apoptosis in cancer cells (Nawrocki et al., 2005; Healy et al., 2009). Therefore, the proapoptotic effects of the UPR may be harnessed as a means to treat cancer.

The UPR in neurodegenerative disorders

In contrast to the indispensable role of the UPR in secretory cells, its function in the physiology of the nervous system is not fully understood. Studies in Xbp1-null neurons revealed that XBP1s regulates the induction of GABAergic markers including somatostatin, neuropeptide Y, and calbindin through brain-derived neurotrophic factor signaling to control the neurite extension (Hayashi et al., 2007, 2008). A polymorphism in the XBP1 promoter was linked to a risk factor for bipolar disorder and schizophrenia (Kakiuchi et al., 2003a). Interestingly, translational control of ATF4 mediated by GCN2–eIF2α phosphorylation appears important for hippocampal synaptic plasticity and memory (Costa-Mattioli et al., 2005). Targeting inactivation of ATF4 can enhance synaptic plasticity and memory storage (Chen et al., 2003). Nevertheless, the function of ATF6 and PERK–eIF2α phosphorylation in the nervous system remains to be determined.

Although the role of the UPR in the nervous system remains speculative, activation of the UPR is observed in a number of neurodegenerative diseases including amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, Parkinson’s disease, Huntington’s disease, prion-related disorders, and Alzheimer’s disease, and demyelinating neurodegenerative autoimmune diseases such as multiple sclerosis, Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease, and transverse myelitis (Doyle et al., 2011; Matus et al., 2011). Interestingly, the pathogenic contribution of the UPR is highly specific in different disease models. Chop deletion shortened lifespan and increased oligodendrocyte death in mice with Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease, whereas Chop deletion attenuated neurotoxin-induced Parkinson’s disease (Gow and Wrabetz, 2009). In addition, deletion of Xbp1 delayed ALS disease onset and increased life span due to an increase in autophagy (Hetz et al., 2009), whereas deletion of Xbp1 did not affect neuronal loss or animal survival in a prion-related disorder disease mouse model (Hetz and Soto, 2006). Thus, the importance of the UPR in neurodegeneration appears disease specific, which introduces challenges to study the functional significance of ER stress in the pathogenesis of these disorders.

Future perspectives

Although by no means exhaustive, Table 1 summarizes the physiological functions of the UPR components in mouse models and the genetic association of these components with human disease. The UPR contains considerable sensitivity and flexibility to exquisitely regulate ER activity and adapt cells to different physiological conditions. As the phase of the UPR shifts from a protective stage to proapoptotic, the UPR commits cells to death, which can concurrently intersect with inflammatory signaling pathways to either initiate or exacerbate pathogenic states. Despite tremendous progress in understanding the physiological significance of the UPR as well as the cross talk between the UPR, metabolic, inflammatory, and other signaling pathways, real-time analysis of protein folding in the ER and UPR activation has only been performed in yeast (Merksamer et al., 2008). Thus, the mechanisms involved in stimulating and sustaining UPR signals in the pathogenesis of different diseases is still unknown. Further studies on identifying these mechanisms will greatly facilitate approaches to modulate UPR activity to reach a desired therapeutic benefit.

Table 1.

Physiological functions of UPR components in mouse models and their genetic association with human disease

| Gene | Factors that regulate expression | Phenotypes of knockout mouse model | Genetic association with human diseases | References |

| IRE1α | N.A. | (1) Embryonic lethality at E12.5 due to liver hypoplasia; (2) Liver deletion: hypolipidemia | (1) Human somatic cancers | Zhang et al., 2005, 2011; Greenman et al., 2007 |

| XBP1s | XBP1s and ATF6α | (1) Embryonic lethality at E13.5 due to liver hypoplasia; (2) Liver deletion: hypolipidemia; (3) Intestinal epithelial cell deletion: enteritis; (4) Pancreatic acinar cell deletion: extensive pancreas regeneration; (5) Pancreatic β cell deletion: hyperglycemia; (6) Neuron deletion: leptin resistance | (1) Inflammatory bowel disease; (2) Schizophrenia in the Japanese population; (3) Bipolar disorder; (4) Ischemic stroke | Kakiuchi et al., 2003b, 2004; Kaser et al., 2008; Yilmaz et al., 2010 |

| ATF6α | N.A. | (1) Susceptible to pharmacologically induced ER stress | (1) Type 2 diabetes and pre-diabetic traits; (2) Increased plasma cholesterol levels | Chu et al., 2007; Wu et al., 2007; Meex et al., 2009 |

| CREBH | PPARα, HNF4α, and ATF6α | (1) Hypoferremia and spleen iron sequestration; (2) Hyperlipidemia; (3) Liver knockdown: fasting hyperglycemia | (1) Extreme hypertriglyceridemia | Zhang et al., 2006; Vecchi et al., 2009; J.H. Lee et al., 2011 |

| PERK | N.A. | (1) Neonatal hyperglycemia | (1) Wolcott-Rallison syndrome; (2) Supranuclear palsy | Delépine et al., 2000; Höglinger et al., 2011 |

| ATF4 | CHOP | (1) Delayed bone formation; (2) Severe fetal anemia; (3) Increased insulin sensitivity; (4) Defects in long-term memory | N.A. | Elefteriou et al., 2006; Costa-Mattioli et al., 2007; Yamaguchi et al., 2008 |

| CHOP | ATF4 and ATF6α | (1) Protected from pharmacologically induced ER stress; (2) Protected from type 2 diabetes; (3) Protected from atherosclerosis; (4) Protected from leukodystrophy Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease | (1) Early-onset type 2 diabetes in Italians | Oyadomari et al., 2002; Marciniak et al., 2004; Silva et al., 2005; Gragnoli, 2008; Song et al., 2008 |

| WFS1 | XBP1s | (1) Diabetes due to insufficient insulin secretion; (2) Growth retardation | (1) Wolfram syndrome; (2) Risk of type 2 diabetes in Japanese and European populations | Karasik et al., 1989; Inoue et al., 1998; Ishihara et al., 2004; Mita et al., 2008 |

| ORMDL3 | N.A. | N.A. | (1) Ulcerative colitis; (2) Risk of childhood asthma | Hjelmqvist et al., 2002; Breslow et al., 2010; McGovern et al., 2010 |

| Grp78 (BiP) | ATF6α and ATF4 | (1) Embryonic lethality at E3.5 due to impaired embryo peri-implantation; (2) Liver deletion: simultaneous liver damage and hepatic steatosis | (1) Bipolar disorder | Kakiuchi et al., 2005; Luo et al., 2006; R. Ye et al., 2010 |

| SIL1 | XBP1s | (1) Adult-onset ataxia with cerebellar Purkinje cell loss | (1) Marinesco-Sjogren syndrome; (2) Alzheimer’s disease | Tyson and Stirling, 2000; Anttonen et al., 2005; Zhao et al., 2005, 2010 |

| Grp94 | XBP1s, ATF6α, and ATF4 | (1) Embryonic lethality at E7; (2) B cell deletion: reduced antibody production; (3) Bone marrow deletion: hematopoietic stem cell expansion | (1) Bipolar disorder | Kakiuchi et al., 2007; Mao et al., 2010 |

| P58 IPK | XBP1s and ATF6α | (1) Diabetes | N.A. | Ladiges et al., 2005 |

| Calnexin | XBP1s and ATF6α | (1) Postnatal death; (2) Motor disorder | N.A. | Denzel et al., 2002 |

| Calreticulin | XBP1s and ATF6α | (1) Embryonic lethality at E14.5 | (1) A case of schizophrenia | Aghajani et al., 2006 |

| Seleno-protein S | N.A. | (1) Disturbed redox homeostasis in the liver and cataract development in eyes | (1) Inflammatory response; (2) Non-small cell lung cancer | Hart et al., 2011; Kasaikina et al., 2011 |

N.A., not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We apologize to those who we were unable to reference due to space limitations.

R.J. Kaufman is supported by National Institutes of Health grants P01 HL057346, R37 DK042394, R01 DK088227, R24 DK093074, and R01 HL052173. S. Wang is supported by postdoctoral fellowship from the American Heart Association.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper:

- ATF

- activating transcription factor

- C/EBP

- CCAAT enhancer-binding protein

- CHOP

- C/EBP homologous protein

- elF2α

- eukaryotic translational initiation factor 2α

- IRE

- inositol-requiring transmembrane kinase/endoribonuclease

- PERK

- protein kinase-like eukaryotic initiation factor 2α kinase

- UPR

- unfolded protein response

- XBP

- X-box binding protein

References

- Acosta-Alvear D., Zhou Y., Blais A., Tsikitis M., Lents N.H., Arias C., Lennon C.J., Kluger Y., Dynlacht B.D. 2007. XBP1 controls diverse cell type- and condition-specific transcriptional regulatory networks. Mol. Cell. 27:53–66 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aghajani A., Rahimi A., Fadai F., Ebrahimi A., Najmabadi H., Ohadi M. 2006. A point mutation at the calreticulin gene core promoter conserved sequence in a case of schizophrenia. Am. J. Med. Genet. B. Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 141B:294–295 10.1002/ajmg.b.30300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allagnat F., Christulia F., Ortis F., Pirot P., Lortz S., Lenzen S., Eizirik D.L., Cardozo A.K. 2010. Sustained production of spliced X-box binding protein 1 (XBP1) induces pancreatic beta cell dysfunction and apoptosis. Diabetologia. 53:1120–1130 10.1007/s00125-010-1699-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anttonen A.K., Mahjneh I., Hämäläinen R.H., Lagier-Tourenne C., Kopra O., Waris L., Anttonen M., Joensuu T., Kalimo H., Paetau A., et al. 2005. The gene disrupted in Marinesco-Sjögren syndrome encodes SIL1, an HSPA5 cochaperone. Nat. Genet. 37:1309–1311 10.1038/ng1677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auf G., Jabouille A., Guérit S., Pineau R., Delugin M., Bouchecareilh M., Magnin N., Favereaux A., Maitre M., Gaiser T., et al. 2010. Inositol-requiring enzyme 1alpha is a key regulator of angiogenesis and invasion in malignant glioma. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 107:15553–15558 10.1073/pnas.0914072107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Back S.H., Scheuner D., Han J., Song B., Ribick M., Wang J., Gildersleeve R.D., Pennathur S., Kaufman R.J. 2009. Translation attenuation through eIF2alpha phosphorylation prevents oxidative stress and maintains the differentiated state in beta cells. Cell Metab. 10:13–26 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey D., O’Hare P. 2007. Transmembrane bZIP transcription factors in ER stress signaling and the unfolded protein response. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 9:2305–2321 10.1089/ars.2007.1796 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basseri S., Lhoták S., Sharma A.M., Austin R.C. 2009. The chemical chaperone 4-phenylbutyrate inhibits adipogenesis by modulating the unfolded protein response. J. Lipid Res. 50:2486–2501 10.1194/jlr.M900216-JLR200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batchvarova N., Wang X.Z., Ron D. 1995. Inhibition of adipogenesis by the stress-induced protein CHOP (Gadd153). EMBO J. 14:4654–4661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertolotti A., Zhang Y., Hendershot L.M., Harding H.P., Ron D. 2000. Dynamic interaction of BiP and ER stress transducers in the unfolded-protein response. Nat. Cell Biol. 2:326–332 10.1038/35014014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bobrovnikova-Marjon E., Grigoriadou C., Pytel D., Zhang F., Ye J., Koumenis C., Cavener D., Diehl J.A. 2010. PERK promotes cancer cell proliferation and tumor growth by limiting oxidative DNA damage. Oncogene. 29:3881–3895 10.1038/onc.2010.153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyce M., Bryant K.F., Jousse C., Long K., Harding H.P., Scheuner D., Kaufman R.J., Ma D., Coen D.M., Ron D., Yuan J. 2005. A selective inhibitor of eIF2alpha dephosphorylation protects cells from ER stress. Science. 307:935–939 10.1126/science.1101902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslow D.K., Collins S.R., Bodenmiller B., Aebersold R., Simons K., Shevchenko A., Ejsing C.S., Weissman J.S. 2010. Orm family proteins mediate sphingolipid homeostasis. Nature. 463:1048–1053 10.1038/nature08787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavener D.R., Gupta S., McGrath B.C. 2010. PERK in beta cell biology and insulin biogenesis. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 21:714–721 10.1016/j.tem.2010.08.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cazanave S.C., Elmi N.A., Akazawa Y., Bronk S.F., Mott J.L., Gores G.J. 2010. CHOP and AP-1 cooperatively mediate PUMA expression during lipoapoptosis. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 299:G236–G243 10.1152/ajpgi.00091.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen A., Muzzio I.A., Malleret G., Bartsch D., Verbitsky M., Pavlidis P., Yonan A.L., Vronskaya S., Grody M.B., Cepeda I., et al. 2003. Inducible enhancement of memory storage and synaptic plasticity in transgenic mice expressing an inhibitor of ATF4 (CREB-2) and C/EBP proteins. Neuron. 39:655–669 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00501-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng G., Feng Z., He B. 2005. Herpes simplex virus 1 infection activates the endoplasmic reticulum resident kinase PERK and mediates eIF-2alpha dephosphorylation by the gamma(1)34.5 protein. J. Virol. 79:1379–1388 10.1128/JVI.79.3.1379-1388.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu W.S., Das S.K., Wang H., Chan J.C., Deloukas P., Froguel P., Baier L.J., Jia W., McCarthy M.I., Ng M.C., et al. 2007. Activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6) sequence polymorphisms in type 2 diabetes and pre-diabetic traits. Diabetes. 56:856–862 10.2337/db06-1305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa-Mattioli M., Gobert D., Harding H., Herdy B., Azzi M., Bruno M., Bidinosti M., Ben Mamou C., Marcinkiewicz E., Yoshida M., et al. 2005. Translational control of hippocampal synaptic plasticity and memory by the eIF2alpha kinase GCN2. Nature. 436:1166–1173 10.1038/nature03897 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa-Mattioli M., Gobert D., Stern E., Gamache K., Colina R., Cuello C., Sossin W., Kaufman R., Pelletier J., Rosenblum K., et al. 2007. eIF2alpha phosphorylation bidirectionally regulates the switch from short- to long-term synaptic plasticity and memory. Cell. 129:195–206 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross B.C., Bond P.J., Sadowski P.G., Jha B.K., Zak J., Goodman J.M., Silverman R.H., Neubert T.A., Baxendale I.R., Ron D., Harding H.P. 2012. The molecular basis for selective inhibition of unconventional mRNA splicing by an IRE1-binding small molecule. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 109:E869–E878 10.1073/pnas.1115623109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crozat A., Aman P., Mandahl N., Ron D. 1993. Fusion of CHOP to a novel RNA-binding protein in human myxoid liposarcoma. Nature. 363:640–644 10.1038/363640a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cullinan S.B., Zhang D., Hannink M., Arvisais E., Kaufman R.J., Diehl J.A. 2003. Nrf2 is a direct PERK substrate and effector of PERK-dependent cell survival. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:7198–7209 10.1128/MCB.23.20.7198-7209.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delépine M., Nicolino M., Barrett T., Golamaully M., Lathrop G.M., Julier C. 2000. EIF2AK3, encoding translation initiation factor 2-alpha kinase 3, is mutated in patients with Wolcott-Rallison syndrome. Nat. Genet. 25:406–409 10.1038/78085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denzel A., Molinari M., Trigueros C., Martin J.E., Velmurgan S., Brown S., Stamp G., Owen M.J. 2002. Early postnatal death and motor disorders in mice congenitally deficient in calnexin expression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:7398–7404 10.1128/MCB.22.21.7398-7404.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimopoulos M.A., San-Miguel J.F., Anderson K.C. 2011. Emerging therapies for the treatment of relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. Eur. J. Haematol. 86:1–15 10.1111/j.1600-0609.2010.01542.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorner A.J., Wasley L.C., Kaufman R.J. 1989. Increased synthesis of secreted proteins induces expression of glucose-regulated proteins in butyrate-treated Chinese hamster ovary cells. J. Biol. Chem. 264:20602–20607 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle K.M., Kennedy D., Gorman A.M., Gupta S., Healy S.J., Samali A. 2011. Unfolded proteins and endoplasmic reticulum stress in neurodegenerative disorders. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 15:2025–2039 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2011.01374.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elefteriou F., Benson M.D., Sowa H., Starbuck M., Liu X., Ron D., Parada L.F., Karsenty G. 2006. ATF4 mediation of NF1 functions in osteoblast reveals a nutritional basis for congenital skeletal dysplasiae. Cell Metab. 4:441–451 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.10.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagone P., Jackowski S. 2009. Membrane phospholipid synthesis and endoplasmic reticulum function. J. Lipid Res. 50:S311–S316 10.1194/jlr.R800049-JLR200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fels D.R., Koumenis C. 2006. The PERK/eIF2alpha/ATF4 module of the UPR in hypoxia resistance and tumor growth. Cancer Biol. Ther. 5:723–728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonseca S.G., Ishigaki S., Oslowski C.M., Lu S., Lipson K.L., Ghosh R., Hayashi E., Ishihara H., Oka Y., Permutt M.A., Urano F. 2010. Wolfram syndrome 1 gene negatively regulates ER stress signaling in rodent and human cells. J. Clin. Invest. 120:744–755 10.1172/JCI39678 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franks P.W., Rolandsson O., Debenham S.L., Fawcett K.A., Payne F., Dina C., Froguel P., Mohlke K.L., Willer C., Olsson T., et al. 2008. Replication of the association between variants in WFS1 and risk of type 2 diabetes in European populations. Diabetologia. 51:458–463 10.1007/s00125-007-0887-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu S., Watkins S.M., Hotamisligil G.S. 2012. The role of endoplasmic reticulum in hepatic lipid homeostasis and stress signaling. Cell Metab. 15:623–634 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.03.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujimoto T., Yoshimatsu K., Watanabe K., Yokomizo H., Otani T., Matsumoto A., Osawa G., Onda M., Ogawa K. 2007. Overexpression of human X-box binding protein 1 (XBP-1) in colorectal adenomas and adenocarcinomas. Anticancer Res. 27(1A):127–131 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner B.M., Walter P. 2011. Unfolded proteins are Ire1-activating ligands that directly induce the unfolded protein response. Science. 333:1891–1894 10.1126/science.1209126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh R., Lipson K.L., Sargent K.E., Mercurio A.M., Hunt J.S., Ron D., Urano F. 2010. Transcriptional regulation of VEGF-A by the unfolded protein response pathway. PLoS ONE. 5:e9575 10.1371/journal.pone.0009575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gow A., Wrabetz L. 2009. CHOP and the endoplasmic reticulum stress response in myelinating glia. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 19:505–510 10.1016/j.conb.2009.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gragnoli C. 2008. CHOP T/C and C/T haplotypes contribute to early-onset type 2 diabetes in Italians. J. Cell. Physiol. 217:291–295 10.1002/jcp.21553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenman C., Stephens P., Smith R., Dalgliesh G.L., Hunter C., Bignell G., Davies H., Teague J., Butler A., Stevens C., et al. 2007. Patterns of somatic mutation in human cancer genomes. Nature. 446:153–158 10.1038/nature05610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han D., Lerner A.G., Vande Walle L., Upton J.P., Xu W., Hagen A., Backes B.J., Oakes S.A., Papa F.R. 2009. IRE1alpha kinase activation modes control alternate endoribonuclease outputs to determine divergent cell fates. Cell. 138:562–575 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding H.P., Novoa I., Zhang Y., Zeng H., Wek R., Schapira M., Ron D. 2000a. Regulated translation initiation controls stress-induced gene expression in mammalian cells. Mol. Cell. 6:1099–1108 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)00108-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding H.P., Zhang Y., Bertolotti A., Zeng H., Ron D. 2000b. Perk is essential for translational regulation and cell survival during the unfolded protein response. Mol. Cell. 5:897–904 10.1016/S1097-2765(00)80330-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harding H.P., Zhang Y., Zeng H., Novoa I., Lu P.D., Calfon M., Sadri N., Yun C., Popko B., Paules R., et al. 2003. An integrated stress response regulates amino acid metabolism and resistance to oxidative stress. Mol. Cell. 11:619–633 10.1016/S1097-2765(03)00105-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart K., Landvik N.E., Lind H., Skaug V., Haugen A., Zienolddiny S. 2011. A combination of functional polymorphisms in the CASP8, MMP1, IL10 and SEPS1 genes affects risk of non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 71:123–129 10.1016/j.lungcan.2010.04.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi A., Kasahara T., Iwamoto K., Ishiwata M., Kametani M., Kakiuchi C., Furuichi T., Kato T. 2007. The role of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)-induced XBP1 splicing during brain development. J. Biol. Chem. 282:34525–34534 10.1074/jbc.M704300200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayashi A., Kasahara T., Kametani M., Kato T. 2008. Attenuated BDNF-induced upregulation of GABAergic markers in neurons lacking Xbp1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 376:758–763 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.09.059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healy S.J., Gorman A.M., Mousavi-Shafaei P., Gupta S., Samali A. 2009. Targeting the endoplasmic reticulum-stress response as an anticancer strategy. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 625:234–246 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.06.064 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetz C.A., Soto C. 2006. Stressing out the ER: a role of the unfolded protein response in prion-related disorders. Curr. Mol. Med. 6:37–43 10.2174/156652406775574578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hetz C., Thielen P., Matus S., Nassif M., Court F., Kiffin R., Martinez G., Cuervo A.M., Brown R.H., Glimcher L.H. 2009. XBP-1 deficiency in the nervous system protects against amyotrophic lateral sclerosis by increasing autophagy. Genes Dev. 23:2294–2306 10.1101/gad.1830709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hjelmqvist L., Tuson M., Marfany G., Herrero E., Balcells S., Gonzalez-Duarte R. 2002. ORMDL proteins are a conserved new family of endoplasmic reticulum membrane proteins. Genome Biol. 3:RESEARCH0027. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/gb-2002-3-6-research0027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Höglinger G.U., Melhem N.M., Dickson D.W., Sleiman P.M., Wang L.S., Klei L., Rademakers R., de Silva R., Litvan I., Riley D.E., et al. ; PSP Genetics Study Group 2011. Identification of common variants influencing risk of the tauopathy progressive supranuclear palsy. Nat. Genet. 43:699–705 10.1038/ng.859 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollien J., Lin J.H., Li H., Stevens N., Walter P., Weissman J.S. 2009. Regulated Ire1-dependent decay of messenger RNAs in mammalian cells. J. Cell Biol. 186:323–331 10.1083/jcb.200903014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotamisligil G.S. 2010. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and the inflammatory basis of metabolic disease. Cell. 140:900–917 10.1016/j.cell.2010.02.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C.J., Lin C.Y., Haataja L., Gurlo T., Butler A.E., Rizza R.A., Butler P.C. 2007. High expression rates of human islet amyloid polypeptide induce endoplasmic reticulum stress mediated beta-cell apoptosis, a characteristic of humans with type 2 but not type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 56:2016–2027 10.2337/db07-0197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue H., Tanizawa Y., Wasson J., Behn P., Kalidas K., Bernal-Mizrachi E., Mueckler M., Marshall H., Donis-Keller H., Crock P., et al. 1998. A gene encoding a transmembrane protein is mutated in patients with diabetes mellitus and optic atrophy (Wolfram syndrome). Nat. Genet. 20:143–148 10.1038/2441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishihara H., Takeda S., Tamura A., Takahashi R., Yamaguchi S., Takei D., Yamada T., Inoue H., Soga H., Katagiri H., et al. 2004. Disruption of the WFS1 gene in mice causes progressive beta-cell loss and impaired stimulus-secretion coupling in insulin secretion. Hum. Mol. Genet. 13:1159–1170 10.1093/hmg/ddh125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itoh N., Sei T., Nose K., Okamoto H. 1978. Glucose stimulation of the proinsulin synthesis in isolated pancreatic islets without increasing amount of proinsulin mRNA. FEBS Lett. 93:343–347 10.1016/0014-5793(78)81136-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwakoshi N.N., Pypaert M., Glimcher L.H. 2007. The transcription factor XBP-1 is essential for the development and survival of dendritic cells. J. Exp. Med. 204:2267–2275 10.1084/jem.20070525 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwawaki T., Akai R., Yamanaka S., Kohno K. 2009. Function of IRE1 alpha in the placenta is essential for placental development and embryonic viability. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 106:16657–16662 10.1073/pnas.0903775106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji C., Kaplowitz N., Lau M.Y., Kao E., Petrovic L.M., Lee A.S. 2011. Liver-specific loss of glucose-regulated protein 78 perturbs the unfolded protein response and exacerbates a spectrum of liver diseases in mice. Hepatology. 54:229–239 10.1002/hep.24368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakiuchi C., Iwamoto K., Ishiwata M., Bundo M., Kasahara T., Kusumi I., Tsujita T., Okazaki Y., Nanko S., Kunugi H., et al. 2003a. Impaired feedback regulation of XBP1 as a genetic risk factor for bipolar disorder. Nat. Genet. 35:171–175 10.1038/ng1235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakiuchi C., Iwamoto K., Ishiwata M., Bundo M., Kasahara T., Kusumi I., Tsujita T., Okazaki Y., Nanko S., Kunugi H., et al. 2003b. Impaired feedback regulation of XBP1 as a genetic risk factor for bipolar disorder. Nat. Genet. 35:171–175 10.1038/ng1235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakiuchi C., Ishiwata M., Umekage T., Tochigi M., Kohda K., Sasaki T., Kato T. 2004. Association of the XBP1-116C/G polymorphism with schizophrenia in the Japanese population. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 58:438–440 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2004.01280.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakiuchi C., Ishiwata M., Nanko S., Kunugi H., Minabe Y., Nakamura K., Mori N., Fujii K., Umekage T., Tochigi M., et al. 2005. Functional polymorphisms of HSPA5: possible association with bipolar disorder. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 336:1136–1143 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.08.248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kakiuchi C., Ishiwata M., Nanko S., Kunugi H., Minabe Y., Nakamura K., Mori N., Fujii K., Umekage T., Tochigi M., et al. 2007. Association analysis of HSP90B1 with bipolar disorder. J. Hum. Genet. 52:794–803 10.1007/s10038-007-0188-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kammoun H.L., Chabanon H., Hainault I., Luquet S., Magnan C., Koike T., Ferré P., Foufelle F. 2009. GRP78 expression inhibits insulin and ER stress-induced SREBP-1c activation and reduces hepatic steatosis in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 119:1201–1215 10.1172/JCI37007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karasik A., O’Hara C., Srikanta S., Swift M., Soeldner J.S., Kahn C.R., Herskowitz R.D. 1989. Genetically programmed selective islet beta-cell loss in diabetic subjects with Wolfram’s syndrome. Diabetes Care. 12:135–138 10.2337/diacare.12.2.135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kars M., Yang L., Gregor M.F., Mohammed B.S., Pietka T.A., Finck B.N., Patterson B.W., Horton J.D., Mittendorfer B., Hotamisligil G.S., Klein S. 2010. Tauroursodeoxycholic Acid may improve liver and muscle but not adipose tissue insulin sensitivity in obese men and women. Diabetes. 59:1899–1905 10.2337/db10-0308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasaikina M.V., Fomenko D.E., Labunskyy V.M., Lachke S.A., Qiu W., Moncaster J.A., Zhang J., Wojnarowicz M.W., Jr., Natarajan S.K., Malinouski M., et al. 2011. Roles of the 15-kDa selenoprotein (Sep15) in redox homeostasis and cataract development revealed by the analysis of Sep 15 knockout mice. J. Biol. Chem. 286:33203–33212 10.1074/jbc.M111.259218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaser A., Lee A.H., Franke A., Glickman J.N., Zeissig S., Tilg H., Nieuwenhuis E.E., Higgins D.E., Schreiber S., Glimcher L.H., Blumberg R.S. 2008. XBP1 links ER stress to intestinal inflammation and confers genetic risk for human inflammatory bowel disease. Cell. 134:743–756 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaser A., Flak M.B., Tomczak M.F., Blumberg R.S. 2011. The unfolded protein response and its role in intestinal homeostasis and inflammation. Exp. Cell Res. 317:2772–2779 10.1016/j.yexcr.2011.07.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman R.J. 2002. Orchestrating the unfolded protein response in health and disease. J. Clin. Invest. 110:1389–1398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman R.J. 2004. Regulation of mRNA translation by protein folding in the endoplasmic reticulum. Trends Biochem. Sci. 29:152–158 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman R.J., Scheuner D., Schröder M., Shen X., Lee K., Liu C.Y., Arnold S.M. 2002. The unfolded protein response in nutrient sensing and differentiation. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3:411–421 10.1038/nrm829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koong A.C., Chauhan V., Romero-Ramirez L. 2006. Targeting XBP-1 as a novel anti-cancer strategy. Cancer Biol. Ther. 5:756–759 10.4161/cbt.5.7.2973 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladiges W.C., Knoblaugh S.E., Morton J.F., Korth M.J., Sopher B.L., Baskin C.R., MacAuley A., Goodman A.G., LeBoeuf R.C., Katze M.G. 2005. Pancreatic beta-cell failure and diabetes in mice with a deletion mutation of the endoplasmic reticulum molecular chaperone gene P58IPK. Diabetes. 54:1074–1081 10.2337/diabetes.54.4.1074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laybutt D.R., Preston A.M., Akerfeldt M.C., Kench J.G., Busch A.K., Biankin A.V., Biden T.J. 2007. Endoplasmic reticulum stress contributes to beta cell apoptosis in type 2 diabetes. Diabetologia. 50:752–763 10.1007/s00125-006-0590-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee A.S. 2007. GRP78 induction in cancer: therapeutic and prognostic implications. Cancer Res. 67:3496–3499 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee A.H., Iwakoshi N.N., Glimcher L.H. 2003. XBP-1 regulates a subset of endoplasmic reticulum resident chaperone genes in the unfolded protein response. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:7448–7459 10.1128/MCB.23.21.7448-7459.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee A.H., Scapa E.F., Cohen D.E., Glimcher L.H. 2008. Regulation of hepatic lipogenesis by the transcription factor XBP1. Science. 320:1492–1496 10.1126/science.1158042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee A.H., Heidtman K., Hotamisligil G.S., Glimcher L.H. 2011. Dual and opposing roles of the unfolded protein response regulated by IRE1alpha and XBP1 in proinsulin processing and insulin secretion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 108:8885–8890 10.1073/pnas.1105564108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.H., Giannikopoulos P., Duncan S.A., Wang J., Johansen C.T., Brown J.D., Plutzky J., Hegele R.A., Glimcher L.H., Lee A.H. 2011. The transcription factor cyclic AMP-responsive element-binding protein H regulates triglyceride metabolism. Nat. Med. 17:812–815 10.1038/nm.2347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee M.W., Chanda D., Yang J., Oh H., Kim S.S., Yoon Y.S., Hong S., Park K.G., Lee I.K., Choi C.S., et al. 2010. Regulation of hepatic gluconeogenesis by an ER-bound transcription factor, CREBH. Cell Metab. 11:331–339 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.02.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonardi R., Frank M.W., Jackson P.D., Rock C.O., Jackowski S. 2009. Elimination of the CDP-ethanolamine pathway disrupts hepatic lipid homeostasis. J. Biol. Chem. 284:27077–27089 10.1074/jbc.M109.031336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipson K.L., Fonseca S.G., Ishigaki S., Nguyen L.X., Foss E., Bortell R., Rossini A.A., Urano F. 2006. Regulation of insulin biosynthesis in pancreatic beta cells by an endoplasmic reticulum-resident protein kinase IRE1. Cell Metab. 4:245–254 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo S., Mao C., Lee B., Lee A.S. 2006. GRP78/BiP is required for cell proliferation and protecting the inner cell mass from apoptosis during early mouse embryonic development. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26:5688–5697 10.1128/MCB.00779-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma K., Vattem K.M., Wek R.C. 2002. Dimerization and release of molecular chaperone inhibition facilitate activation of eukaryotic initiation factor-2 kinase in response to endoplasmic reticulum stress. J. Biol. Chem. 277:18728–18735 10.1074/jbc.M200903200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra J.D., Miao H., Zhang K., Wolfson A., Pennathur S., Pipe S.W., Kaufman R.J. 2008. Antioxidants reduce endoplasmic reticulum stress and improve protein secretion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 105:18525–18530 10.1073/pnas.0809677105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao C., Wang M., Luo B., Wey S., Dong D., Wesselschmidt R., Rawlings S., Lee A.S. 2010. Targeted mutation of the mouse Grp94 gene disrupts development and perturbs endoplasmic reticulum stress signaling. PLoS ONE. 5:e10852 10.1371/journal.pone.0010852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marciniak S.J., Yun C.Y., Oyadomari S., Novoa I., Zhang Y., Jungreis R., Nagata K., Harding H.P., Ron D. 2004. CHOP induces death by promoting protein synthesis and oxidation in the stressed endoplasmic reticulum. Genes Dev. 18:3066–3077 10.1101/gad.1250704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinon F., Chen X., Lee A.H., Glimcher L.H. 2010. TLR activation of the transcription factor XBP1 regulates innate immune responses in macrophages. Nat. Immunol. 11:411–418 10.1038/ni.1857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matus S., Glimcher L.H., Hetz C. 2011. Protein folding stress in neurodegenerative diseases: a glimpse into the ER. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 23:239–252 10.1016/j.ceb.2011.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGovern D.P., Gardet A., Törkvist L., Goyette P., Essers J., Taylor K.D., Neale B.M., Ong R.T., Lagacé C., Li C., et al. ; NIDDK IBD Genetics Consortium 2010. Genome-wide association identifies multiple ulcerative colitis susceptibility loci. Nat. Genet. 42:332–337 10.1038/ng.549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meex S.J., van Greevenbroek M.M., Ayoubi T.A., Vlietinck R., van Vliet-Ostaptchouk J.V., Hofker M.H., Vermeulen V.M., Schalkwijk C.G., Feskens E.J., Boer J.M., et al. 2007. Activating transcription factor 6 polymorphisms and haplotypes are associated with impaired glucose homeostasis and type 2 diabetes in Dutch Caucasians. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 92:2720–2725 10.1210/jc.2006-2280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meex S.J., Weissglas-Volkov D., van der Kallen C.J., Thuerauf D.J., van Greevenbroek M.M., Schalkwijk C.G., Stehouwer C.D., Feskens E.J., Heldens L., Ayoubi T.A., et al. 2009. The ATF6-Met[67]Val substitution is associated with increased plasma cholesterol levels. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 29:1322–1327 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.180240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merksamer P.I., Trusina A., Papa F.R. 2008. Real-time redox measurements during endoplasmic reticulum stress reveal interlinked protein folding functions. Cell. 135:933–947 10.1016/j.cell.2008.10.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimura N., Fulciniti M., Gorgun G., Tai Y.T., Cirstea D., Santo L., Hu Y., Fabre C., Minami J., Ohguchi H., et al. 2012. Blockade of XBP1 splicing by inhibition of IRE1alpha is a promising therapeutic option in multiple myeloma. Blood. http://dx.doi.org/10.1182/blood-2011-07-366633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mita M., Miyake K., Zenibayashi M., Hirota Y., Teranishi T., Kouyama K., Sakaguchi K., Kasuga M. 2008. Association study of the effect of WFS1 polymorphisms on risk of type 2 diabetes in Japanese population. Kobe J. Med. Sci. 54:E192–E199 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nawrocki S.T., Carew J.S., Dunner K., Jr., Boise L.H., Chiao P.J., Huang P., Abbruzzese J.L., McConkey D.J. 2005. Bortezomib inhibits PKR-like endoplasmic reticulum (ER) kinase and induces apoptosis via ER stress in human pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Res. 65:11510–11519 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishitoh H., Matsuzawa A., Tobiume K., Saegusa K., Takeda K., Inoue K., Hori S., Kakizuka A., Ichijo H. 2002. ASK1 is essential for endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced neuronal cell death triggered by expanded polyglutamine repeats. Genes Dev. 16:1345–1355 10.1101/gad.992302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohoka N., Yoshii S., Hattori T., Onozaki K., Hayashi H. 2005. TRB3, a novel ER stress-inducible gene, is induced via ATF4-CHOP pathway and is involved in cell death. EMBO J. 24:1243–1255 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ota T., Gayet C., Ginsberg H.N. 2008. Inhibition of apolipoprotein B100 secretion by lipid-induced hepatic endoplasmic reticulum stress in rodents. J. Clin. Invest. 118:316–332 10.1172/JCI32752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyadomari S., Koizumi A., Takeda K., Gotoh T., Akira S., Araki E., Mori M. 2002. Targeted disruption of the Chop gene delays endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated diabetes. J. Clin. Invest. 109:525–532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozcan U., Yilmaz E., Ozcan L., Furuhashi M., Vaillancourt E., Smith R.O., Görgün C.Z., Hotamisligil G.S. 2006. Chemical chaperones reduce ER stress and restore glucose homeostasis in a mouse model of type 2 diabetes. Science. 313:1137–1140 10.1126/science.1128294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papandreou I., Denko N.C., Olson M., Van Melckebeke H., Lust S., Tam A., Solow-Cordero D.E., Bouley D.M., Offner F., Niwa M., Koong A.C. 2011. Identification of an Ire1alpha endonuclease specific inhibitor with cytotoxic activity against human multiple myeloma. Blood. 117:1311–1314 10.1182/blood-2010-08-303099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park S.W., Zhou Y., Lee J., Lu A., Sun C., Chung J., Ueki K., Ozcan U. 2010. The regulatory subunits of PI3K, p85alpha and p85beta, interact with XBP-1 and increase its nuclear translocation. Nat. Med. 16:429–437 10.1038/nm.2099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Promlek T., Ishiwata-Kimata Y., Shido M., Sakuramoto M., Kohno K., Kimata Y. 2011. Membrane aberrancy and unfolded proteins activate the endoplasmic reticulum stress sensor Ire1 in different ways. Mol. Biol. Cell. 22:3520–3532 10.1091/mbc.E11-04-0295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puthalakath H., O’Reilly L.A., Gunn P., Lee L., Kelly P.N., Huntington N.D., Hughes P.D., Michalak E.M., McKimm-Breschkin J., Motoyama N., et al. 2007. ER stress triggers apoptosis by activating BH3-only protein Bim. Cell. 129:1337–1349 10.1016/j.cell.2007.04.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy J.K., Rao M.S. 2006. Lipid metabolism and liver inflammation. II. Fatty liver disease and fatty acid oxidation. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 290:G852–G858 10.1152/ajpgi.00521.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimold A.M., Etkin A., Clauss I., Perkins A., Friend D.S., Zhang J., Horton H.F., Scott A., Orkin S.H., Byrne M.C., et al. 2000. An essential role in liver development for transcription factor XBP-1. Genes Dev. 14:152–157 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimold A.M., Iwakoshi N.N., Manis J., Vallabhajosyula P., Szomolanyi-Tsuda E., Gravallese E.M., Friend D., Grusby M.J., Alt F., Glimcher L.H. 2001. Plasma cell differentiation requires the transcription factor XBP-1. Nature. 412:300–307 10.1038/35085509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutkowski D.T., Arnold S.M., Miller C.N., Wu J., Li J., Gunnison K.M., Mori K., Sadighi Akha A.A., Raden D., Kaufman R.J. 2006. Adaptation to ER stress is mediated by differential stabilities of pro-survival and pro-apoptotic mRNAs and proteins. PLoS Biol. 4:e374 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutkowski D.T., Wu J., Back S.H., Callaghan M.U., Ferris S.P., Iqbal J., Clark R., Miao H., Hassler J.R., Fornek J., et al. 2008. UPR pathways combine to prevent hepatic steatosis caused by ER stress-mediated suppression of transcriptional master regulators. Dev. Cell. 15:829–840 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.10.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sammels E., Parys J.B., Missiaen L., De Smedt H., Bultynck G. 2010. Intracellular Ca2+ storage in health and disease: a dynamic equilibrium. Cell Calcium. 47:297–314 10.1016/j.ceca.2010.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheuner D., Song B., McEwen E., Liu C., Laybutt R., Gillespie P., Saunders T., Bonner-Weir S., Kaufman R.J. 2001. Translational control is required for the unfolded protein response and in vivo glucose homeostasis. Mol. Cell. 7:1165–1176 10.1016/S1097-2765(01)00265-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheuner D., Vander Mierde D., Song B., Flamez D., Creemers J.W., Tsukamoto K., Ribick M., Schuit F.C., Kaufman R.J. 2005. Control of mRNA translation preserves endoplasmic reticulum function in beta cells and maintains glucose homeostasis. Nat. Med. 11:757–764 10.1038/nm1259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schewe D.M., Aguirre-Ghiso J.A. 2008. ATF6alpha-Rheb-mTOR signaling promotes survival of dormant tumor cells in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 105:10519–10524 10.1073/pnas.0800939105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schindler A.J., Schekman R. 2009. In vitro reconstitution of ER-stress induced ATF6 transport in COPII vesicles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 106:17775–17780 10.1073/pnas.0910342106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schröder M., Kaufman R.J. 2005. The mammalian unfolded protein response. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 74:739–789 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.074134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuck S., Prinz W.A., Thorn K.S., Voss C., Walter P. 2009. Membrane expansion alleviates endoplasmic reticulum stress independently of the unfolded protein response. J. Cell Biol. 187:525–536 10.1083/jcb.200907074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sha H., He Y., Chen H., Wang C., Zenno A., Shi H., Yang X., Zhang X., Qi L. 2009. The IRE1alpha-XBP1 pathway of the unfolded protein response is required for adipogenesis. Cell Metab. 9:556–564 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.04.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J., Chen X., Hendershot L., Prywes R. 2002. ER stress regulation of ATF6 localization by dissociation of BiP/GRP78 binding and unmasking of Golgi localization signals. Dev. Cell. 3:99–111 10.1016/S1534-5807(02)00203-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi Y., Vattem K.M., Sood R., An J., Liang J., Stramm L., Wek R.C. 1998. Identification and characterization of pancreatic eukaryotic initiation factor 2 alpha-subunit kinase, PEK, involved in translational control. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:7499–7509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva R.M., Ries V., Oo T.F., Yarygina O., Jackson-Lewis V., Ryu E.J., Lu P.D., Marciniak S.J., Ron D., Przedborski S., et al. 2005. CHOP/GADD153 is a mediator of apoptotic death in substantia nigra dopamine neurons in an in vivo neurotoxin model of parkinsonism. J. Neurochem. 95:974–986 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03428.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song B., Scheuner D., Ron D., Pennathur S., Kaufman R.J. 2008. Chop deletion reduces oxidative stress, improves beta cell function, and promotes cell survival in multiple mouse models of diabetes. J. Clin. Invest. 118:3378–3389 10.1172/JCI34587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stutzmann G.E., Mattson M.P. 2011. Endoplasmic reticulum Ca(2+) handling in excitable cells in health and disease. Pharmacol. Rev. 63:700–727 10.1124/pr.110.003814 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thameem F., Farook V.S., Bogardus C., Prochazka M. 2006. Association of amino acid variants in the activating transcription factor 6 gene (ATF6) on 1q21-q23 with type 2 diabetes in Pima Indians. Diabetes. 55:839–842 10.2337/diabetes.55.03.06.db05-1002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorp E., Li G., Seimon T.A., Kuriakose G., Ron D., Tabas I. 2009. Reduced apoptosis and plaque necrosis in advanced atherosclerotic lesions of Apoe−/− and Ldlr−/− mice lacking CHOP. Cell Metab. 9:474–481 10.1016/j.cmet.2009.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsaytler P., Harding H.P., Ron D., Bertolotti A. 2011. Selective inhibition of a regulatory subunit of protein phosphatase 1 restores proteostasis. Science. 332:91–94 10.1126/science.1201396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyson J.R., Stirling C.J. 2000. LHS1 and SIL1 provide a lumenal function that is essential for protein translocation into the endoplasmic reticulum. EMBO J. 19:6440–6452 10.1093/emboj/19.23.6440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usui M., Yamaguchi S., Tanji Y., Tominaga R., Ishigaki Y., Fukumoto M., Katagiri H., Mori K., Oka Y., Ishihara H. 2012. Atf6alpha-null mice are glucose intolerant due to pancreatic beta-cell failure on a high-fat diet but partially resistant to diet-induced insulin resistance. Metabolism. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.metabol.2012.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vecchi C., Montosi G., Zhang K., Lamberti I., Duncan S.A., Kaufman R.J., Pietrangelo A. 2009. ER stress controls iron metabolism through induction of hepcidin. Science. 325:877–880 10.1126/science.1176639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y., Vera L., Fischer W.H., Montminy M. 2009. The CREB coactivator CRTC2 links hepatic ER stress and fasting gluconeogenesis. Nature. 460:534–537 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woo C.W., Cui D., Arellano J., Dorweiler B., Harding H., Fitzgerald K.A., Ron D., Tabas I. 2009. Adaptive suppression of the ATF4-CHOP branch of the unfolded protein response by toll-like receptor signalling. Nat. Cell Biol. 11:1473–1480 10.1038/ncb1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J., Rutkowski D.T., Dubois M., Swathirajan J., Saunders T., Wang J., Song B., Yau G.D., Kaufman R.J. 2007. ATF6alpha optimizes long-term endoplasmic reticulum function to protect cells from chronic stress. Dev. Cell. 13:351–364 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao C., Giacca A., Lewis G.F. 2011. Sodium phenylbutyrate, a drug with known capacity to reduce endoplasmic reticulum stress, partially alleviates lipid-induced insulin resistance and beta-cell dysfunction in humans. Diabetes. 60:918–924 10.2337/db10-1433 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi H., Wang H.G. 2004. CHOP is involved in endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis by enhancing DR5 expression in human carcinoma cells. J. Biol. Chem. 279:45495–45502 10.1074/jbc.M406933200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi S., Ishihara H., Yamada T., Tamura A., Usui M., Tominaga R., Munakata Y., Satake C., Katagiri H., Tashiro F., et al. 2008. ATF4-mediated induction of 4E-BP1 contributes to pancreatic beta cell survival under endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell Metab. 7:269–276 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto K., Sato T., Matsui T., Sato M., Okada T., Yoshida H., Harada A., Mori K. 2007. Transcriptional induction of mammalian ER quality control proteins is mediated by single or combined action of ATF6alpha and XBP1. Dev. Cell. 13:365–376 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.07.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto K., Takahara K., Oyadomari S., Okada T., Sato T., Harada A., Mori K. 2010. Induction of liver steatosis and lipid droplet formation in ATF6alpha-knockout mice burdened with pharmacological endoplasmic reticulum stress. Mol. Biol. Cell. 21:2975–2986 10.1091/mbc.E09-02-0133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]