Abstract

Rationale

High fasting serum lipid levels are significant risk factors for atherosclerosis. However, the contributions of postprandial excursions in serum lipoproteins to atherogenesis are less well characterized.

Objective

This study aims to delineate whether changes in intestinal lipid absorption associated with loss of inositol requiring enzyme 1β (Ire1β) would affect the development of hyperlipidemia and atherosclerosis in Apoe−/− mice.

Methods and Results

We used Ire1β deficient mice to assess the contribution of intestinal lipid absorption to atherosclerosis. Here we show that Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− mice contain higher levels of intestinal microsomal triglyceride transfer protein, absorb more lipids, develop hyperlipidemia, and have higher levels of atherosclerotic plaques compared to Apoe−/− mice when fed chow and western diets.

Conclusions

These studies indicate that Ire1β regulates intestinal lipid absorption and that increased intestinal lipoprotein production contributes to atherosclerosis.

Keywords: Lipid absorption, intestine, atherosclerosis, cholesterol, Ire1β, MTP, ApoB

Introduction

Excess plasma lipids are risk factors for various cardiovascular and metabolic diseases1. The relationship between excess plasma lipids and cardiovascular disease is based on lipid measurements made in the fasting state. This implies that fasting lipemia due to increased hepatic lipoprotein production or delayed catabolism of hepatic derived lipoproteins drives the increased cardiovascular risk. However, humans spend much of day in a postprandial (fed) state and it has been proposed that chylomicron remnants arising during postprandial state also contribute to atherosclerosis because these particles are taken up by arterial smooth muscle cells2, 3, 4. A role for absorbed lipids in atherosclerosis is supported by the association of atherosclerosis with delayed elimination of postprandial triglyceride-rich lipoproteins5; the presence of apoB48 in the atherosclerotic plaque6; uptake and retention of chylomicron remnants in the arterial wall7; and increased inflammatory response to postprandial lipoproteins8. A problem associated with establishing a relationship between intestinal lipoproteins and atherosclerosis is the presence of and associated changes in hepatic lipoproteins in the postprandial state. For example, it is well known that absorption of lipids during postprandial state is also associated with increased secretion of hepatic lipoproteins5. Veniant et al9 showed that postprandial atherogenicity might be correlated with apoB48-contaning lipoproteins. However, comparison of atherosclerosis in apoB48 and apoB100 only mice in Apoe−/− background indicated that atherosclerosis was more likely related to plasma cholesterol concentration and was independent of the apoB molecules9.

To address this issue we took advantage of our previous observations that Ire1β is only expressed in the intestine10–12 and that it suppresses intestinal lipid absorption by regulating MTP13, 14; a critical chaperone required for the assembly and secretion of apoB-containing lipoproteins 15–17. Mechanistic studies have shown that Ire1β decreases MTP mRNA involving post-transcriptional degradation13. These studies also showed that hyperlipidemia observed in Ire1b−/− mice on high cholesterol and high fat diet is due to increased intestinal lipid absorption with little contribution from hepatic lipoprotein production. However, it was not clear from these studies whether this hyperlipidemia represents a response to high dietary cholesterol and fat or diets rich in high cholesterol and fat accelerate development of this phenotype. Another question remained unanswered was whether changes in intestinal lipid absorption would affect atherosclerosis. Here we address the role of the selective increase in intestinal lipid absorption associated with loss of Ire1β in the development of hyperlipidemia and atherosclerosis in Apoe−/− mice.

Methods

Materials

[14C]cholesterol, [3H]cholesterol, [3H]oleic acid, and [3H]triolein were from NEN LifeScience Products. Oleic acid, cholate, deoxycholate, taurocholate, and monoacylglycerol were procured from Sigma. Phosphatidylcholine was from Avanti Polar Lipids. Other chemicals and solvents were purchased from Fisher Scientific.

Mice and Diets

ApoE-deficient (Apoe−/−) mice on a C57Bl/6J background were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Ire1b−/− mice11, originally of a 129svev background, were backcrossed with C57Bl/6J Apoe−/− mice for 8 generations to generate Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− mice. Mice were housed in an air-conditioned room at 22 ± 0.5 °C with a 12-h lighting schedule (700–1900 h). Mice were kept on a chow diet (Research Diets, Inc) or fed a western-type diet (0.15% cholesterol, 20% saturated fat, Research Diets, Inc). Only male mice were used in these experiments to avoid the effects of hormonal changes on plasma lipids. Experiments involving animals were conducted with the approval of State University of New York Downstate Medical Center Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Plasma lipid and cytokine measurements

Total cholesterol and triglyceride levels were measured using kits (Thermo Trace, Melbourne, Australia). HDL lipids were measured after precipitating apoB lipoproteins18. Plasma cytokines were detected using the Mouse Common Cytokines Multi-Analyte ELISArray Kit from SABiosciences according to the manufacturer’s guidelines.

Lipoprotein characterization

Plasma lipoproteins were isolated by gel filtration (flow rate of 0.2 ml/min, 200-µl fractions, 10 mM Tris, pH 7.4 buffer) using a Superose 6 column. VLDL/LDL fractions were pooled and their % composition was determined. Further, they were subjected to negative staining and electron microscopy 19. Lipoproteins (d<1.006) were also isolated by ultracentrifugation (Beckman Coulter Optima Tabletop Ultracentrifuge, TLA-100 rotor, 100,000 rpm, 180 min, 4 °C) after overlaying 150 µl of plasma with 6 ml of <1.006 g/ml solution. The top (200µl) was collected and used for composition analysis and negative staining.

Postprandial lipid absorption

For postprandial lipid measurements, plasma samples were collected at 22:00 h (3 h after lights were turned off). For daytime restricted feeding experiments, mice had access to food only from 9:30 AM to 01:30 PM for 10 days. On the last day, blood was withdrawn at hourly intervals for 6 h starting from 9:30 AM (just before the food was given). Total cholesterol and triglyceride levels were measured in the plasma as described above.

Hepatic lipid mobilization and metabolic studies

Hepatic triglyceride secretion rates were determined in vivo 20. Mice were fasted for 16 h and injected intraperitoneally with poloxamer 407 (30 mg/mouse). Blood samples were drawn before injection and every 30 min for 3 h for triglyceride determinations. In a separate experiment, mice were fasted for 16 h and intraperitoneally administered with [35S]-Promix (Perkin Elmer) along with poloxamer 407 (30 mg/mouse). To study hepatic apoB secretion, apoB-containing lipoproteins were immunoprecipitated from the plasma, separated on gel, dried, and fluorographed. Albumin was used as a control.

Short-term lipid absorption studies

Age-matched male mice (4 per group) on a chow diet for 1 year or western diet for 6 weeks were fasted overnight and injected intraperitoneally with poloxamer 407 (30 mg/mouse). After 1 h, mice were gavaged with 0.5 µCi of either [3H]triolein or [14C]cholesterol with 0.2 mg of unlabeled cholesterol in 15 µl of olive oil21. After 2 h, plasma was used to measure radioactivity.

Uptake and secretion of lipids by primary enterocytes

To study uptake, primary enterocytes from overnight fasted Apoe−/− and Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− mice (n=3) were suspended in 4 ml of DMEM containing 0.5 µCi/ml of [3H]oleic acid or [3H]cholesterol and incubated at 37°C18, 21. After 1 h, enterocytes were washed and lipids were isolated to determine uptake of radiolabeled lipids. For characterization of secreted lipoproteins, enterocytes were isolated from overnight fasted mice and labeled for 1 h with 0.5 µCi/ml of [3H]oleic acid or [3H]cholesterol. Enterocytes were washed and incubated with fresh media containing 1.4 mM oleic acid containing micelles 18, 22. After 2 h, enterocytes were centrifuged and supernatants were collected. In [3H]oleic acid labeling experiment, lipids were isolated from the media and separated on thin layer chromatography to quantify incorporation of [3H]oleic acid into triglycerides and phospholipids. In [3H]cholesterol labeling experiment, media was subjected to density gradient ultracentrifugation to determine its secretion with different lipoproteins18.

Determination of MTP activity and mRNA levels

Small pieces (0.1 g) of liver and proximal small intestine (~ 1-cm) were homogenized in low-salt buffer, centrifuged, and supernatants were used for protein determination and the MTP assay23, 24 using a kit (Chylos, Inc). Total RNA from tissues was isolated using TriZol (Invitrogen) and MTP mRNA levels were determined13.

Mouse atherosclerotic lesion measurement

The aortas were dissected and the arches photographed25. Exposed aortas were stained with Oil Red O and en face assay was performed25. The heart was fixed in 4% formaldehyde and then embedded in paraffin. The aortic root was sectioned into 7 µm thick slices and then stained with Harris's hematoxylin and eosin. Histological and morphological analysis of collagen was performed after Masson’s trichrome staining (Richard-Allan Scientific) of these sections. Images were viewed and captured with a Nikon Labophot 2 microscope equipped with a SPOT RT3 color video camera attached to a computerized imaging system. The average area of these aortic root lesions from each animal was quantified using Image–Pro Plus version 4.5 (Media Cybernetics Inc).

Results

Ablation of IRE1β in chow fed Apoe−/− mice increases plasma lipids

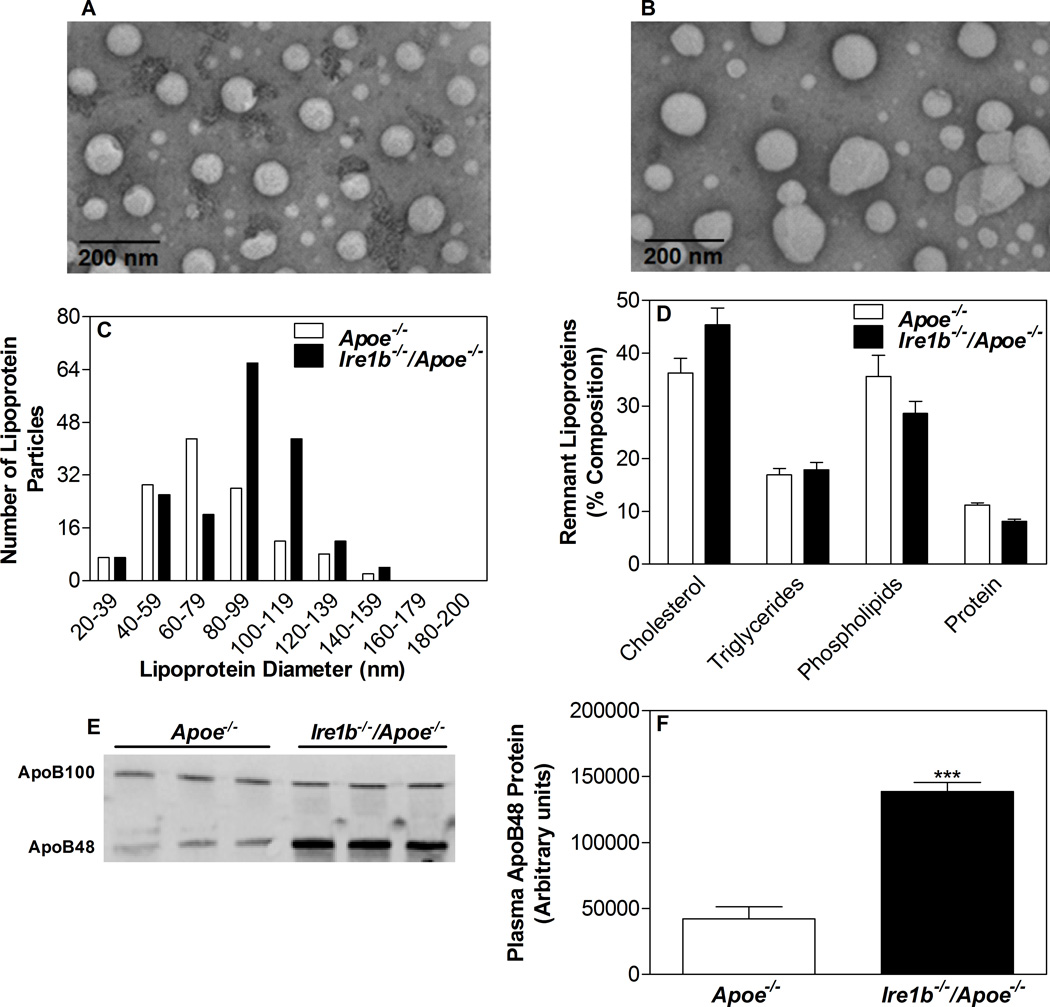

We have shown previously that Ire1b affects lipid absorption during high cholesterol or western diet feeding13. We wondered whether IRE1β knockout mice will develop hyperlipidemia on ApoE knockout background when fed a chow diet. Another question we asked was whether these mice will be more susceptible to atherosclerosis. To evaluate the role of IRE1β on hyperlipidemia and atherosclerosis, we crossed Ire1b−/− mice with Apoe−/− mice to generate Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− mice. There was no significant change in the body weight of these mice after 12 months on chow diet (Table 1). Furthermore, these mice did not register any significant differences in fasting plasma glucose, phospholipids, and free fatty acid levels (Table 1). But, Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− mice showed a significant increase of 56% and 40% in fasting plasma triglyceride and cholesterol (Table 1), respectively, compared with Apoe−/− mice mainly due to augmentations in apoB-containing lipoproteins (Suppl Fig IA–B). Further, plasma of Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− mice had 43% more pro-atherogenic apoB48 levels compared to Apoe−/− mice (Suppl Fig IC–D). Negative staining and electron microscopy (Suppl Fig IE, Apoe−/−; IF, Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/−) showed an increase in particles with diameter of 80–140 nm in Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− mice (Suppl Fig IG), but compositional analysis did not reveal any differences between the two groups (Suppl Fig IH). Characterization of plasma lipoproteins was also performed after isolating d<1.006 g/ml lipoproteins by ultracentrifugation (Fig 1A, Apoe−/−; 1B, Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/−). Again, there were more particles with diameters ranging between 80–140 nm (Fig 1C) with no significant differences in the composition of these particles (Fig 1D). Western blot analysis revealed ~ 3.3-fold increase in apoB48 levels (Fig 1E–F). These data indicate that Ire1β deficiency augments hyperlipidemia in Apoe−/− mice by increasing number of apoB-containing remnant lipoproteins with no significant effect on their composition.

Table 1. Deletion of IRE1² in ApoE knockout mice increases plasma lipids and MTP expression.

Apoe−/− and Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− male mice were kept on chow diet for 12 months or fed western diet for 6 weeks. Plasma samples from overnight fasted mice, unless otherwise indicated, were used to measure total lipids. To determine postprandial lipids, plasma was collected at 22:00 h (3h after lights were turned off). Intestine and liver samples were used to measure apoB and MTP. Feces collected over 48 h were used to measure lipids.

| Apoe−/−(n) | Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/−(n) | Apoe−/−(n) | Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/−(n) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Chow diet fed |

Western diet fed |

|||

| Body weight (g) | 32.4 ± 3.3 (8) | 34.1 ± 4.7 (8) | 35.5 ± 4.2 (6) | 34.2 ± 2.9 (8) |

| Plasma glucose (mg/dl) | 191.8 ± 36.8 (8) | 195.6 ± 32.3 (8) | 341.9 ± 65.8 (6) | 410.6 ± 125.6(8) |

| Plasma Phospholipids (mg/dl) | 431.8 ± 32.5 (8) | 471.2 ± 45.2 (8) | 559.2 ± 17.2 (6) | 606.9 ± 106.3(8) |

| Plasma free fatty acids (mg/dl) | 1.15 ± 0.1 (8) | 1.26 ± 0.17 (8) | 2.35 ± 0.23 (6) | 3.31 ± 0.79 (8) |

| Plasma triglycerides (mg/dl) | ||||

| Fasting | 113.5 ± 10.9 (8) | 177.5 ± 16.3 (8)*** | 46.5 ± 16.6 (6) | 104.9 ± 27.8 (8)*** |

| Postprandial | 154.4 ± 31.9 (4) | 262.3 ± 37.4 (4)** | ND | ND |

| Plasma cholesterol (mg/dl) | ||||

| Fasting | 596.5 ± 35.2 (8) | 836.7 ± 72.0 (8)*** | 1298.0 ± 71.4 (6) | 1851.8 ± 212.1(8)*** |

| Postprandial | 716.6 ± 120.1 (4) | 1119.8 ± 161.8 (4)** | ND | ND |

| MTP activity (% Transfer/mg/h) | ||||

| Intestinal | 870.2 ± 30.3 (8) | 1221.3 ± 57.6 (8)*** | 983.5 ± 52.4 (6) | 1387.4 ± 77.4(8)*** |

| Hepatic | 577.0 + 55.8 (8) | 609.8 + 60.7 (8) | 456.5 ± 62.3 (6) | 402.1 ± 43.2 (8) |

| MTP mRNA (fold change) | ||||

| Intestinal | 0.995 ± 0.18 (8) | 1.470 ± 0.12 (8)*** | 1.100 ± 0.27 (6) | 1.794 ± 0.26 (8)** |

| Hepatic | 1.023 ± 0.18 (8) | 1.165 ± 0.26 (8) | 0.965 ± 0.23 (6) | 0.737 ± 0.25 (8) |

| ApoB mRNA (fold change) | ||||

| Intestinal | 1.109 ± 0.38 (8) | 1.045 ± 0.30 (8) | ND | ND |

| Hepatic | 1.062 ± 0.22 (8) | 1.199 ± 0.28 (8) | ND | ND |

| Fecal lipids (µmol/mouse/day) | ||||

| Triglycerides | 3.315 ± 0.480 (6) | 2.520 ± 0.442 (6) * | ND | ND |

| Cholesterol | 0.130 ± 0.022 (6) | 0.088 ± 0.017 (6)** | ND | ND |

Values are mean ± SD.

p<0.01 and

p<0.001 compared to Apoe−/−. ND, not determined.

Figure 1. Deletion of IRE1β in ApoE knockout mice increases plasma apoB-lipoprotein particles.

(A–F) Apoe−/− and Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− male mice (n=3) were kept on chow diet for 12 months. Plasma d<1.006 g/ml lipoproteins were isolated by density gradient ultracentrifugation. Negative staining and electron microscopy (A, Apoe−/−; B, Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/−) were performed to determine diameter of lipoprotein particles in each group and plotted as histogram (C). These samples were also used to determine % composition (D) and apoB100 and apoB48 levels by western blotting (E). Quantification of ApoB48 was done using Image J (F). Values are mean ± SD. ***p<0.001 compared to Apoe−/−.

Hyperlipidemia due to increased lipid absorption in chow fed Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− mice

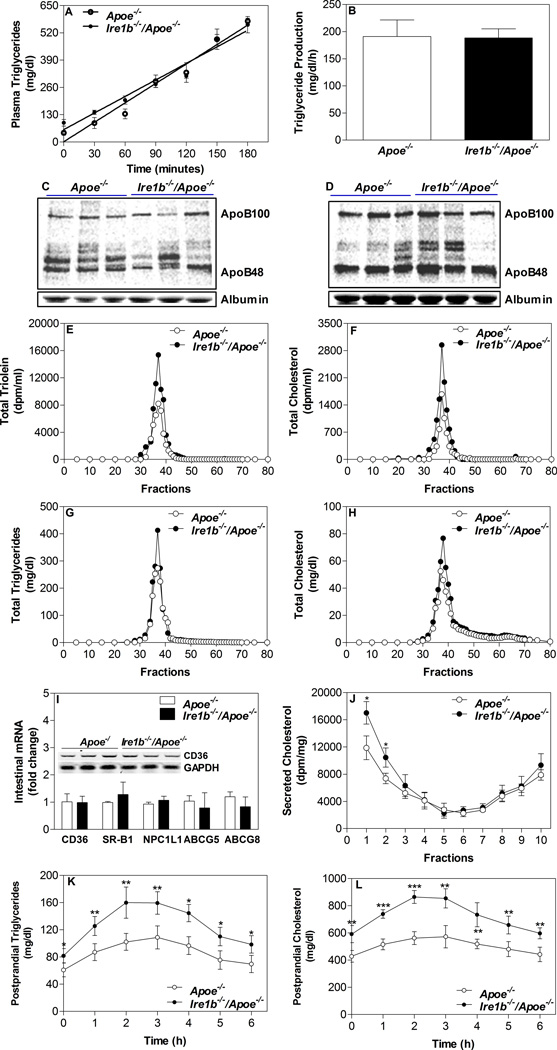

Next, we attempted to elucidate mechanisms for the origin of apoB-lipoproteins and hyperlipidemia in these mice. Increases in plasma apoB-lipoproteins in Apoe−/− mice that are deficient in clearing apoB-lipoproteins could be explained by their enhanced assembly and secretion by the liver and/or intestine. First, we determined hepatic secretion of triglycerides in these mice. Overnight fasted animals were injected with lipoprotein lipase inhibitor poloxamer P407 and 35S-Promix, and plasma lipids and nascent apolipoproteins were determined. There were no differences in time-dependent increases in plasma triglycerides (Fig 2A) and triglyceride production rates were similar between Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− (188.7 ± 16.7 mg/dl/h) and Apoe−/− (191.2 ± 30.6 mg/dl/h) mice (Fig 2B). Moreover, these mice had similar plasma levels of nascent apoB48, apoB100 and albumin (Fig 2C–D). Thus, differences in plasma lipids are not related to changes in hepatic lipoprotein production.

Figure 2. Secretion of lipids by Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− enterocytes.

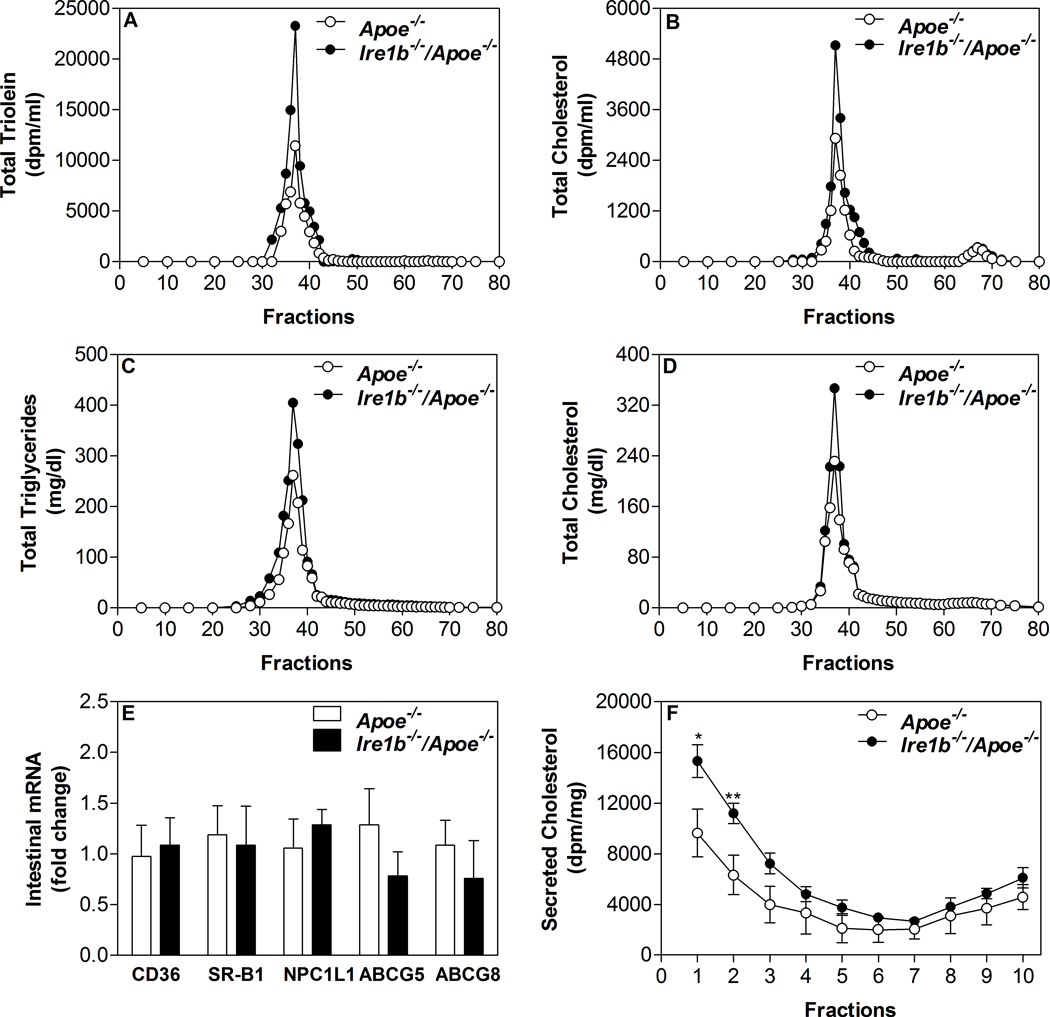

(A–D) Hepatic lipoprotein production: Apoe−/− and Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− male mice (n=3) fed a chow diet for 12 months were fasted overnight and injected intraperitoneally with [35S]-Promix (Perkin Elmer) along with poloxamer 407 (30 mg/mouse). Blood was withdrawn at the baseline and every 30 min after the injection for 3 h. Triglycerides were measured at each time and plotted against time (A). Rate of production was calculated using values between 1h and 3 h time points (B). To study hepatic apoB secretion, apoB-containing lipoproteins at 1 h (C) and 3 h (D) were immunoprecipitated from the plasma, separated on gel, dried, and fluorographed. Albumin was used as a control. (E–H) Intestinal lipoprotein production: Apoe−/− and Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− male mice were fed a chow diet (n=4) for 12 months. Mice were fasted overnight and injected intraperitoneally with poloxamer 407 (30 mg/mouse). After 1 h, mice were fed 0.5 µCi of [3H]triolein or [14C]cholesterol as well as 0.2 mg of cholesterol in 15 µL of olive oil. Plasma was collected after 2 h and separated by gel filtration to determine counts (E and F) and mass (G and H) in different lipoproteins. (I) Total RNA isolated from the intestine of Apoe−/− and Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− male mice fed a chow (n=8) diet was used to quantify mRNA levels of CD36, SR-B1, NPC1L1, ABCG5, and ABCG8 (M). Intestines were also used to perform western blotting for CD36 (Inset). (J) Increased cholesterol secretion with chylomicrons by Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− enterocytes: In a different experiment, enterocytes were isolated from chow diet fed overnight fasted mice and labeled for 1 h with 0.5 µCi/ml of [3H]cholesterol. Enterocytes were washed and incubated with fresh media containing 1.4 mM oleic acid containing micelles. Media was used for separating lipoproteins by density gradient ultracentrifugation and radioactivity was determined in separated fractions. Fractions 1–3 represent apoB-containing lipoproteins whereas fractions 8–10 represent non-apoB containing lipoproteins. Each measurement was done in triplicate with 3 mice per group. Mean ± SD, *p<0.05 compared with Apoe−/−. (K–L) Postprandial hyperlipidemia after food entrainment: Apoe−/− and Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− male mice (n=4) fed chow diet for 12 months were subjected to restricted feeding and had access to food only from 9:30 AM to 01:30 PM for 10 days. On the last day, blood was withdrawn at 9:30 AM (just before the food was given) and at hourly intervals. Total triglycerides (K) and cholesterol (L) levels were measured in the plasma at each time point.

Second, we looked at the absorption of lipids by the intestine. Mice fed chow diet for 12 months were injected intraperitoneally with a lipoprotein lipase inhibitor poloxamer P407 and fed with radioactive cholesterol and triolein in olive oil. There was a significant increase in the appearance of [3H]triolein and [14C]cholesterol in the plasma of Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− versus Apoe−/− (Table 2). Gel filtration analysis showed increased lipid counts in the apoB-lipoproteins of Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− mice (Fig 2E–F). Additionally, total mass of triglyceride and cholesterol were increased (Table 2) in apoB-lipoproteins (Fig 2G–H). These studies indicate that Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− mice absorb more lipids via apoB-lipoprotein production.

Table 2. Effect of IRE1² deficiency in ApoE knockout mice on intestinal lipid transport.

Apoe−/− and Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− male mice were fed a chow diet for 12 months or a western diet for 6 weeks. (A) Mice were fasted overnight and injected intraperitoneally with poloxamer 407 (30 mg/mouse). After 1 h, mice were fed 0.5 µCi of [3H]triolein or [14C]cholesterol with 0.2 mg of cholesterol in 15 µL of olive oil. Plasma was collected after 2 h and used to measure triolein and cholesterol counts. Plasma was also used to measure triglyceride and cholesterol mass. Proximal intestinal segment (~10 cm long) was solubilized and used to determine radioactivity. (B) Enterocytes were isolated from overnight fasted mice and incubated for 1 h with 0.5 µCi/ml of [3H]oleic acid or [3H]cholesterol. Enterocytes were washed and lipids were isolated to determine uptake of radiolabel oleic acid or cholesterol. Each measurement was done in triplicate with 3 mice per group. For secretion studies, enterocytes were isolated from overnight fasted mice, labeled for 1 h with 0.5 µCi/ml of [3H]oleic acid or [3H]cholesterol, washed and incubated with fresh media containing 1.4 mM oleic acid containing micelles. Media from oleic acid-labeled enterocytes was separated by thin layer chromatography to measure triglycerides and phospholipids. Media from cholesterol labeled enterocytes was directly quantified. Each measurement was done in triplicate.

| Apoe−/− (n) | Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− (n) | Apoe−/− (n) | Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− (n) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Chow diet fed |

Western diet fed |

|||

| A. Lipid absorption in mice: | ||||

| Plasma lipid mass (mg/dl) | ||||

| Triglycerides | 1550.2 ± 198.1 (4) | 2084.9 ± 167.5 (4)* | 1131.4 ± 71.1 (4) | 1557.7 ± 117.7 (4)** |

| Cholesterol | 1548.4 ± 233.7 (4) | 2076.4 ± 167.4 (4)* | 2371.4 ± 204.6 (4) | 3134.8 ± 216.7 (4)** |

| Plasma radioactivity (dpm/ml) | ||||

| [3H]Triolein | 39617 ± 5699 (4) | 58229 ± 6756 (4)* | 28624 ± 2699 (4) | 44351 ± 4353 (4)* |

| [14C]Cholesterol | 13080 ± 2003 (4) | 18735 ± 2297 (4)* | 9721 ± 1012 (4) | 16318 ± 1377 (4)** |

| Intestinal radioactivity (dpm/g tissue) | ||||

| [3H]Triolein | 224794 ± 38107 (4) | 188416 ± 30089 (4) | ND | ND |

| [14C]Cholesterol | 112552 ± 20185 (4) | 94330 ± 7997 (4) | ND | ND |

| B. Uptake and secretion of lipids by enterocytes: | ||||

| Lipid uptake (dpm/mg protein) | ||||

| Oleic acid | 290620 ±30506 (3) | 280441 ± 28029 (3) | ND | ND |

| Cholesterol | 305779 ± 28048 (3) | 341641 ± 61933 (3) | 340174 ± 24801 (3) | 374769 ± 29077 (3) |

| Lipid secretion (dpm/mg protein) | ||||

| Triglycerides | 63971 ± 7071 (3) | 110685 ± 23446 (3)* | ND | ND |

| Phospholipids | 18235 ± 2288 (3) | 25381 ± 3849 (3) | ND | ND |

| Cholesterol | 37382 ± 5871 (3) | 56306 ± 5137 (3)* | 41140 ± 4196 (3) | 67383 ± 4123 (3)*** |

Values are mean ± SD, n =3.

p<0.05,

p<0.01, and

p<0.001 compared to Apoe−/−. ND, not determined.

Increased intestinal lipid absorption could be due to increased lipid uptake by enterocytes and/or their subsequent enhanced secretion by these cells. To differentiate between these two steps, we assessed the amounts of radioactivity present in the proximal intestine (around 10 cm long) of these mice during short-term absorption studies. There was no significant difference in the levels of intestinal triolein and cholesterol counts between Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− and Apoe−/− mice (Table 2). We also used isolated primary enterocytes to explore mechanisms for enhanced lipid absorption. First, we studied the uptake of oleic acid and cholesterol and found no differences in the uptake (Table 2). To substantiate the observation that oleic acid and cholesterol uptake was not affected, we also measured mRNA levels of candidate transporters. Analysis of the mRNA levels of CD36, SR-B1, NPC1L1, ABCG5, and ABCG8 in the intestine of chow diet fed mice did not register any significant difference between Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− and Apoe−/− mice (Fig 2I). Furthermore, we did not see any change in the levels of CD36 protein (Fig 2I, inset). Hence, Ire1β deficiency does not appear to affect oleic acid or cholesterol uptake by enterocytes.

Next, we studied secretion of oleic acid-labeled lipids by these enterocytes. Secretion of oleic acid-labeled triglycerides was significantly increased by Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− enterocytes (Table 2). Similarly, these enterocytes secreted more cholesterol into the media compared to Apoe−/− enterocytes (Table 2). We have previously shown that cholesterol can be secreted as part of chylomicrons and HDL particles18, 21, 26. Density gradient ultracentrifugation analysis showed that cholesterol secretion was increased in chylomicron fractions (Fig 2J). These results suggest that Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− enterocytes secrete more chylomicrons.

If Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− mice were making more chylomicrons and absorbing more lipids, we reasoned that fecal lipid loss might be lower and plasma lipid levels might be higher during postprandial state in the absence of Ire1β. Although it is known that fecal excretion of fat is low, we measured this in feces collected over 24 h period and observed that fecal triglyceride and cholesterol levels were significantly lower in Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− compared to Apoe−/− mice (Table 1). To determine postprandial lipemia, plasma samples were collected at 22:00 h from Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− and Apoe−/− mice. Plasma triglyceride and cholesterol were significantly higher by 70% and 56%, respectively, in Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− compared to Apoe−/− mice (Table 1). To substantiate further that Ire1β deficiency increases hyperlipidemia at mealtime, we provided food for 4 h during the day for 10 days27–29. Plasma analysis during mealtime showed that Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− mice had higher lipid levels at all times during food availability compared with Apoe−/− mice (Fig 2K–L). These studies indicate that postprandial response in Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− mice is higher than in Apoe−/− mice. Further they show that higher lipids persist even after fasting. Therefore, postprandial hyperlipidemic excursions are more significant and sustained in Ire1β deficient mice.

To understand molecular basis for increases in plasma lipids and lipoproteins, we looked at the expression of apoB and MTP; two proteins critically involved in apoB-lipoprotein assembly and secretion. There was a 40% and 47% increase, respectively, in the intestinal MTP activity and mRNA levels compared with the levels in Apoe−/− mice; in contrast, no significant changes in the hepatic MTP activity and mRNA were noted (Table 1). Furthermore, there were no significant differences in apoB mRNA levels in the intestine and liver of these mice (Table 1). These results suggest that ablation of IRE1β in ApoE null background leads to increased expression of intestinal MTP, but not apoB.

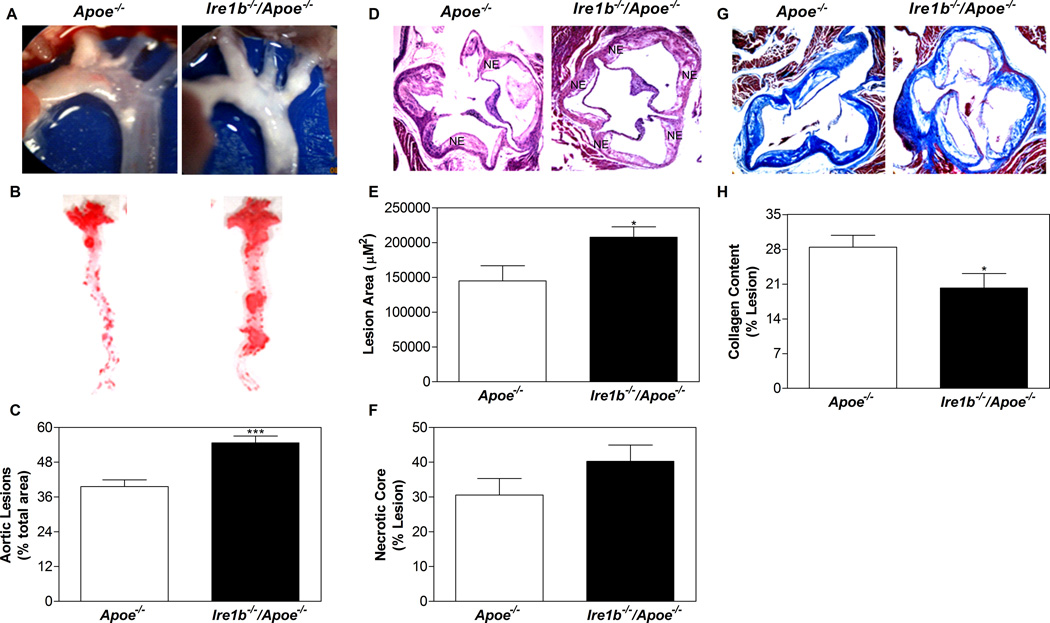

Increased atherosclerosis in Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− mice

To evaluate the impact of IRE1β deficiency on atherogenesis, Apoe−/− and Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− mouse aortas were dissected and photographed after 12 months on chow diet (Fig 3A). Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− mice had more extensive plaques compared to Apoe−/− mice at the branch points. En face analyses of Oil Red O stained thoracic aortic areas exhibited marked increases in atherosclerotic lesions in Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− mice compared to Apoe−/− mice (Fig 3B). Quantification of the stained lesions indicated ~50% increased plaque areas in Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− mice (Fig 3C). Analysis of the plaque morphology in hematoxylin and eosin stained cross sections of the cardiac/aortic junctions revealed substantial differences between Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− and Apoe−/− mice (Fig 3D). Quantification revealed that the proximal aortas of Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− mice had ~43% increased lesion area (Fig 3E). Further, plaques from Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− mice contained more necrotic core (Fig 3D), but percent necrotic core areas in these lesions were not statistically different (Fig 3F). On the other hand, plaques in Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− mice had substantially less collagen (29%), as illustrated by the analysis of Trichrome-stained images (Fig 3G–H). These studies indicate that Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− mice are more susceptible to atherosclerosis than Apoe−/− mice.

Figure 3. Ablation of IRE1β in Apoe−/− mice enhances atherosclerosis.

Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− and Apoe−/− mice were fed a chow diet (n=8) for 12 months. (A) Aortic arch and other proximal arteries were dissected and photographed. A representative photograph from each group is shown. (B–C) Aortas were isolated, stained with Oil Red O (B) and quantified (C). (D–F) Hematoxylin and eosin staining (D) of the proximal aorta (root assay) showing necrotic core (NE) is shown. Quantitative analyses of the lesion (E) and necrotic core (F) were done by Image-Pro-Plus 4.5 software. (G–H) Collagen was stained with Masson’s trichrome (G) and quantified using Image J (H). Values are mean ± SD. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, and ***p<0.001 compared to Apoe−/−.

Accelerated hyperlipidemia and increased atherosclerosis in Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− mice on western diet

Next we studied the effect of a western diet on plasma lipids. Age matched (3 month old males) Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− and Apoe−/− mice were fed a western diet for 6 weeks. Similar to chow fed mice, no difference in the body weights was observed between Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− and Apoe−/− mice on the western diet (Table 1). Again, no differences in the fasting plasma glucose, phospholipids, and free fatty acid levels were observed between Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− and Apoe−/− mice (Table 1). However, the western diet increased fasting plasma triglyceride and cholesterol (Table 1) in Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− mice compared to Apoe−/− mice mainly due to increases in VLDL/LDL fractions (Suppl Fig IIA–B). We then studied changes in MTP levels. Double knockout mice had higher intestinal MTP activity and mRNA levels; but there were no significant differences in the hepatic MTP expression (Table 1). Further, plasma of Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− mice had 93% more pro-atherogenic apoB48 levels compared to Apoe−/− mice (Suppl Fig IIC–D). These studies show that Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− mice develop increased hyperlipidemia when fed a western diet.

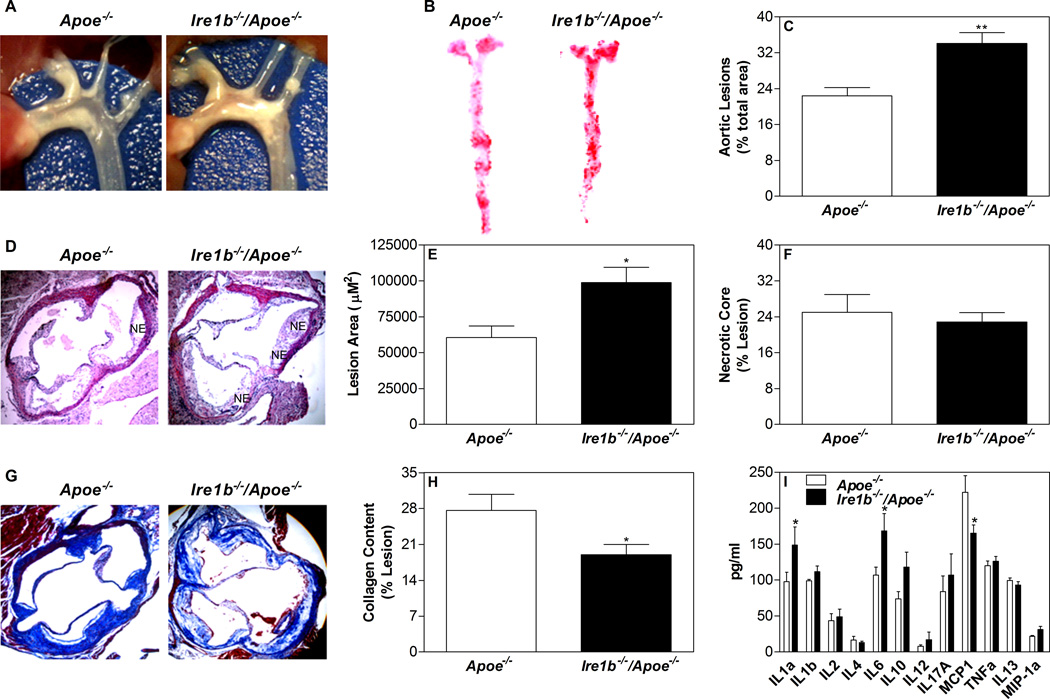

Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− mice had more extensive plaques compared to Apoe−/− mice (Fig 4A) and showed a marked increase (~50%) in atherosclerotic lesions (Fig 4B–C). Analysis of the plaque morphology after hematoxylin/eosin staining (Fig 4D) demonstrated ~63% increase in lesion area (Fig 4E) in the proximal aortas of Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− mice with more necrotic core (Fig 4D), but percent necrotic core area in these lesions were not statistically different (Fig 4F). Trichrome-stained images showed substantially less collagen (30%) in the plaques of Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− mice compared to Apoe−/− mice (Fig 4G–H). Analysis of various cytokines and inflammatory markers in the plasma revealed significant increases in IL-1α, IL-6 and IL-10 in Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− mice (Fig 4I). These studies indicate that Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− mice on a western diet are more susceptible to atherosclerosis than Apoe−/− mice.

Figure 4. Ablation of IRE1β in western diet fed Apoe−/− mice enhances atherosclerosis.

Twelve week old Apoe−/− (n=6) and Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− (n=8) male mice were fed a western diet for 6 weeks. Mice were fasted overnight and sacrificed. (A) Aortic arch and other proximal arteries were dissected and photographed. Representative photographs from each group are shown. (B–C) Aortas were isolated, stained with Oil Red O (B) and quantified (C). (D–F) Hematoxylin and eosin staining (D) of the proximal aorta (root assay) showing necrotic core (NE) is shown. Quantitative analyses of the lesion (E) and necrotic core (F) were done by Image-Pro-Plus 4.5 software. (G–H) Collagen was stained with Masson’s trichrome (G) and quantified using Image J (H). (I) Plasma samples from Apoe−/− and Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− male mice (n=3) were used to measure various cytokines and inflammatory markers using a kit from SA Biosciences (Qiagen). Values are mean ± SD. *p<0.05 and **p<0.01 compared to Apoe−/−.

Mechanistic studies revealed that western diet fed Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− mice absorbed 55% and 68% more [3H]triolein and [14C]cholesterol, respectively, compared to Apoe−/− mice (Table 2). Gel filtration analysis showed increased counts in the apoB-lipoproteins of Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− mice (Fig 5A–B). There was 38% and 32% increase in total triglyceride and cholesterol mass, respectively (Table 2) due to increases in apoB-lipoproteins (Fig 5C–D). These studies indicate that Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− mice absorb more lipids via apoB-lipoprotein production. Next, we studied the uptake of cholesterol by enterocytes isolated from western diet fed mice and found no differences (Table 2). Analysis of the mRNA levels of CD36, SR-B1, NPC1L1, ABCG5, and ABCG8 in the intestine of western diet fed mice also did not register any significant difference between Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− and Apoe−/− mice (Fig 5E). Hence, Ire1β deficiency does not affect cholesterol uptake by enterocytes. However, Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− enterocytes secreted more cholesterol into the media compared to Apoe−/− enterocytes (Table 2) and this increase was mainly in chylomicron fractions (Fig 5F).

Figure 5. Intestines from western diet fed Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− mice secrete more lipids with apoB-lipoproteins.

Twelve week old Apoe−/− and Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− male mice (n=4) were kept on western diet for 6 weeks. (A–D) Mice were fasted overnight and injected intraperitoneally with poloxamer 407 (30 mg/mouse). After 1 hour, mice were fed 0.5 µCi of [3H]triolein or [14C]cholesterol as well as 0.2 mg of cholesterol in 15 µL of olive oil. Plasma was collected after 2 hours and separated by gel filtration to determine counts (A and B) and mass (C and D) in different lipoproteins. (E) Total RNA isolated from the intestine of Apoe−/− (n=3) and Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− (n=5) male mice fed a western diet was used to quantify mRNA levels of CD36, SR-B1, NPC1L1, ABCG5, and ABCG8. (F) To study lipid secretion, enterocytes were isolated from western diet fed overnight fasted mice and labeled for 1 h with 0.5 µCi/ml of [3H]cholesterol. Enterocytes were washed and incubated with fresh media containing 1.4 mM oleic acid containing micelles. Media was used for separating lipoproteins by density gradient ultracentrifugation and radioactivity was determined in each fraction. Fractions 1–3 and 8–10 represent chylomicrons and HDL, respectively. Each measurement was done in triplicate with 3 mice per group. Mean ± SD, *p<0.05 and **p<0.01 compared with Apoe−/−.

Discussion

We previously reported that Ire1β deficiency results in hyperlipidemia in C57Bl/6J mice fed high cholesterol and western diets13. Here, we show that Ire1β deficiency enhances hyperlipidemia in one year old Apoe−/− mice fed a chow diet. Increases in plasma lipids were accelerated when Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− mice were fed a western diet. These studies indicate that Ire1β deficiency increases susceptibility towards hyperlipidemia independent of the genetic background and this propensity is further augmented when more dietary fat is available.

Physiological studies indicated that a major reason for hyperlipidemia in Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− mice compared with Apoe−/− mice was increased intestinal lipid absorption with no significant change in hepatic lipoprotein production (Fig 2A–J). Significant hyperlipidemia persisted in these mice after fasting as well as in daytime during ad libitum feeding. Moreover, food-entrainment studies indicated that hyperlipidemia was more pronounced at the time of food availability (Fig 2K–L). Despite increased absorption there were no significant differences in body weights of Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− and Apoe−/− mice indicating that higher absorption at mealtime results in sustained hyperlipidemia and not in obesity.

Further studies were performed to delineate biochemical mechanisms involved in lipid absorption. These studies showed that Ire1β deficiency has no effect on oleic acid or cholesterol uptake by enterocytes but these enterocytes secrete more lipids with chylomicrons. It is known that free fatty acids are taken up by enterocytes and hepatocytes. After uptake, fatty acids are converted to triglycerides that are either incorporated into newly synthesized lipoproteins and secreted or stored in the cytoplasm. It is also known that lipid secretion is a slower process than fat uptake. For this reason, during postprandial state there is significant accumulation of fat in enterocytes 30. This fat is eventually transported to plasma but after a significant lag. In human studies, it is now well established that dietary lipids ingested in one meal are present in chylomicrons secreted in the following meal 31, 32. Our studies suggest that Ire1β does not affect lipid uptake but it helps in faster intracellular processing and secretion of lipids with intestinal lipoproteins.

We had previously shown that one molecular mechanism for increased intestinal lipid absorption was enhanced MTP expression13. Again, in Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− mice we observed significant augmentations in MTP mRNA and activity with no alterations in hepatic MTP levels. Therefore, it is likely that increases in intestinal MTP expression contributes to increased chylomicron assembly and lipid absorption in the absence of Ire1β. This leads to sustained hyperlipidemia in the absence of ApoE.

It is unclear why enhanced lipid absorption did not increase body weight and why lipoproteins accumulate in the plasma of Ire1β deficient mice. It is likely that plasma lipoprotein lipolysis and their clearance by other tissues are unaltered in the absence of Ire1β. This is supported by our limited studies in the liver that did not show significant differences between Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− and Apoe−/− mice.

Hyperlipidemia is a known risk factor for atherosclerosis. Therefore, we hypothesized that sustained hyperlipidemia might enhance atherosclerosis in Apoe−/− mice. Indeed, we report for the first time that Ire1β deficiency increases atherosclerosis in Apoe−/− mice fed a chow diet. Moreover, the disease development was accelerated when fed a western diet. Overall, there were more lesions throughout the aorta in Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− mice compared to Apoe−/− mice fed either chow or western diets. Therefore, these studies indicate that more intestinal lipoprotein assembly and secretion can contribute to atherogenesis.

Deficiency of Ire1β also resulted into higher levels of plasma apoB48 levels. Veniant et al9 related atherosclerosis more likely to plasma cholesterol concentration although they showed increased postprandial atherogenicity in apoB48 only mice in Apoe−/− background. Presence of apoB48 has been found in atherosclerotic plaques in both animal and human studies and are suspected to be atherogenic 33, 34. Hence, increased plasma apoB48-containing lipoproteins in Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− mice may render these mice more susceptible to atherosclerosis.

In short, these studies support the hypothesis that Ire1β reduces intestinal lipid absorption. They show that Ire1β deficiency increases intestinal lipid absorption mainly due to enhanced chylomicron assembly and secretion. Further, we observed more atherosclerotic plaques in Ire1b−/−/Apoe−/− mice. Thus, increased sustained amounts of intestinal lipoproteins in the absence of Ire1β could contribute to atherogenesis. It is likely that agents that increase expression of Ire1β might reduce hyperlipidemia and atherosclerosis.

Supplementary Material

Novelty and Significance.

What is known?

Excessive plasma concentrations of triglycerides and cholesterol enhance the risk for several prevalent diseases, such as obesity, diabetes, and atherosclerosis.

It has been proposed that chylomicron remnants generated during the postprandial state also contribute to atherosclerosis

What new information does this article contribute?

Ire1β regulated intestinal lipid absorption in Apoe−/− mice.

Ire1β deficiency led to hyperlipidemia in Apoe−/− mice.

The absence of Ire1β increases plasma concentrations of intestinally-derived lipoproteins and contributed to atherogenesis.

Excess plasma lipid concentrations are risk factors for several cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. The relationship between excess lipid concentrations and cardiovascular disease is based on measurements of plasma samples collected during a fasting state. However, humans spend much of the day in a postprandial (fed) state. A confounding factor in interpreting associations between intestinally-derived lipoproteins and development of atherosclerosis is the concomitant change in hepatic lipoproteins in the postprandial state. To address this issue, we took advantage of our previous observation that inositol requiring enzyme 1β (Ire1β) is only expressed in the intestine where it suppresses intestinal lipid absorption by regulating microsomal triglyceride transfer protein (MTP), a critical chaperone required for the assembly and the secretion of apoB-containing lipoproteins. In the present study,, we show that Ire1β deficiency enhances hyperlipidemia in 1 year old Apoe−/− mice fed a normal or saturated fat enriched diet. We demonstrated that that Ire1β deficiency increased atherosclerosis in Apoe−/− mice fed a normal laboratory diet. Moreover, atherosclerotic lesion development was accelerated during feeding a saturated fat enriched diet. Thus, sustained increases in intestinally-derived lipoprotein concentrations due to the absence of Ire1β contributed to atherogenesis. It is likely that agents that increase expression of Ire1β will reduce hyperlipidemia and atherosclerosis.

Acknowledgements

We thank Wei Quan for technical assistance in negative staining and electron microscopy.

Sources of Funding

This work was supported in part by NIH grant DK-46900 to MMH and DK47119 to DR. DR is a Principal Research Fellow of the Wellcome Trust.

Non-standard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- Ire1β

Inositol requiring enzyme 1β

- MTP

microsomal triglyceride transfer protein

- ApoB

apolipoprotein B

- ApoE

apolipoprotein E

- FPLC

fast protein liquid chromatography

Footnotes

Disclosures

None

Reference List

- 1.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Merz CN, Brewer HB, Jr, Clark LT, Hunninghake DB, Pasternak RC, Smith SC, Jr, Stone NJ. Implications of recent clinical trials for the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III guidelines. Circulation. 2004;110:227–239. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000133317.49796.0E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zilversmit DB. Atherogenesis: a postprandial phenomenon. Circulation. 1979;60:473–485. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.60.3.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lopez-Miranda J, Williams C, Lairon D. Dietary, physiological, genetic and pathological influences on postprandial lipid metabolism. Br J Nutr. 2007;98:458–473. doi: 10.1017/S000711450774268X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tomkin GH, Owens D. The chylomicron: relationship to atherosclerosis. Int J Vasc Med. 2012;2012:784536. doi: 10.1155/2012/784536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Karpe F. Postprandial lipoprotein metabolism and atherosclerosis. J Intern Med. 1999;246:341–355. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1999.00548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Proctor SD, Vine DF, Mamo JC. Arterial retention of apolipoprotein B(48)- and B(100)-containing lipoproteins in atherogenesis. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2002;13:461–470. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200210000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Proctor SD, Mamo JCL. Retention of fluorescent-labelled chylomicron remnants within the intima of the arterial wall - evidence that plaque cholesterol may be derived from post-prandial lipoproteins. Eur J Clin Invest. 1998;28:497–503. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.1998.00317.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alipour A, Elte JW, van Zaanen HC, Rietveld AP, Castro CM. Novel aspects of postprandial lipemia in relation to atherosclerosis. Atheroscler Suppl. 2008;9:39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosissup.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Veniant MM, Pierotti V, Newland D, Cham CM, Sanan DA, Walzem RL, Young SG. Susceptibility to atherosclerosis in mice expressing exclusively apolipoprotein B48 or apolipoprotein B100. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:180–188. doi: 10.1172/JCI119511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bertolotti A, Zhang Y, Hendershot LM, Harding HP, Ron D. Dynamic interaction of BiP and ER stress transducers in the unfolded-protein response. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:326–332. doi: 10.1038/35014014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bertolotti A, Wang X, Novoa I, Jungreis R, Schlessinger K, Cho JH, West AB, Ron D. Increased sensitivity to dextran sodium sulfate colitis in IRE1beta-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2001;107:585–593. doi: 10.1172/JCI11476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iwawaki T, Hosoda A, Okuda T, Kamigori Y, Nomura-Furuwatari C, Kimata Y, Tsuru A, Kohno K. Translational control by the ER transmembrane kinase/ribonuclease IRE1 under ER stress. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:158–164. doi: 10.1038/35055065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iqbal J, Dai K, Seimon T, Jungreis R, Oyadomari M, Kuriakose G, Ron D, Tabas I, Hussain MM. IRE1β inhibits chylomicron production by selectively degrading MTP mRNA. Cell Metab. 2008;7:445–455. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dai K, Khatun I, Hussain MM. NR2F1and IRE1β suppress MTP expression and lipoprotein assembly in undifferentiated intestinal epithelial cells. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30:568–574. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.109.198135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hussain MM, Rava P, Walsh M, Rana M, Iqbal J. Multiple functions of microsomal triglyceride transfer protein. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2012;9:14. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-9-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hussain MM, Shi J, Dreizen P. Microsomal triglyceride transfer protein and its role in apolipoprotein B-lipoprotein assembly. J Lipid Res. 2003;44:22–32. doi: 10.1194/jlr.r200014-jlr200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berriot-Varoqueaux N, Aggerbeck LP, Samson-Bouma M, Wetterau JR. The role of the microsomal triglygeride transfer protein in abetalipoproteinemia. Annu Rev Nutr. 2000;20:663–697. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.20.1.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iqbal J, Anwar K, Hussain MM. Multiple, independently regulated pathways of cholesterol transport across the intestinal epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:31610–31620. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301177200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anderson LJ, Boyles JK, Hussain MM. A rapid method for staining large chylomicrons. J Lipid Res. 1989;30:1819–1824. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Millar JS, Cromley DA, McCoy MG, Rader DJ, Billheimer JT. Determining hepatic triglyceride production in mice: comparison of poloxamer 407 with Triton WR-1339. J Lipid Res. 2005;46:2023–2028. doi: 10.1194/jlr.D500019-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iqbal J, Hussain MM. Evidence for multiple complementary pathways for efficient cholesterol absorption in mice. J Lipid Res. 2005;46:1491–1501. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500023-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anwar K, Iqbal J, Hussain MM. Mechanisms involved in vitamin E transport by primary enterocytes and in vivo absorption. J Lipid Res. 2007;48:2028–2038. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M700207-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Athar H, Iqbal J, Jiang XC, Hussain MM. A simple, rapid, and sensitive fluorescence assay for microsomal triglyceride transfer protein. J Lipid Res. 2004;45:764–772. doi: 10.1194/jlr.D300026-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rava P, Athar H, Johnson C, Hussain MM. Transfer of cholesteryl esters and phospholipids as well as net deposition by microsomal triglyceride transfer protein. J Lipid Res. 2005;46:1779–1785. doi: 10.1194/jlr.D400043-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu J, Huan C, Chakraborty M, Zhang H, Lu D, Kuo MS, Cao G, Jiang XC. Macrophage sphingomyelin synthase 2 deficiency decreases atherosclerosis in mice. Circ Res. 2009;105:295–303. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.194613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brunham LR, Kruit JK, Iqbal J, Fievet C, Timmins JA, Pape TD, Coburn BA, Bissada N, Staels B, Groen AK, Hussain MM, Parks JS, Kuipers F, Hayden MR. Intestinal ABCA1 directly contributes to HDL biogenesis in vivo. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1052–1062. doi: 10.1172/JCI27352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pan X, Hussain MM. Diurnal regulation of microsomal triglyceride transfer protein and plasma lipid levels. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:24707–24719. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M701305200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pan X, Hussain MM. Clock is important for food and circadian regulation of macronutrient absorption in mice. J Lipid Res. 2009;50:1800–1813. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M900085-JLR200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pan X, Zhang Y, Wang L, Hussain MM. Diurnal regulation of MTP and plasma triglyceride by CLOCK is mediated by SHP. Cell Metab. 2010;12:174–186. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.05.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Douglass JD, Malik N, Chon SH, Wells K, Zhou YX, Choi AS, Joseph LB, Storch J. Intestinal mucosal triacylglycerol accumulation secondary to decreased lipid secretion in obese and high fat fed mice. Front Physiol. 2012;3:25. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fielding BA, Callow J, Owen RM, Samra JS, Matthews DR, Frayn KN. Postprandial lipemia: the origin of an early peak studied by specific dietary fatty acid intake during sequential meals. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996;63:36–41. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/63.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Robertson MD, Parkes M, Warren BF, Ferguson DJ, Jackson KG, Jewell DP, Frayn KN. Mobilisation of enterocyte fat stores by oral glucose in humans. Gut. 2003;52:834–839. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.6.834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Proctor SD, Mamo JC. Intimal retention of cholesterol derived from apolipoprotein. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:1595–1600. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000084638.14534.0A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pal S, Semorine K, Watts GF, Mamo J. Identification of lipoproteins of intestinal origin in human atherosclerotic plaque. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2003;41:792–795. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2003.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.