Abstract

Background

Efforts to reduce radiation from cardiac computed tomography (CT) are essential. Using a prospectively triggered, high-pitch dual source CT (DSCT) protocol, we aim to determine the radiation dose and image quality (IQ) in patients undergoing pulmonary vein (PV) imaging.

Methods and Results

In 94 patients (61±9 years, 71% male) who underwent 128-slice DSCT (pitch 3.4), radiation dose and IQ were assessed and compared between 69 patients in sinus rhythm (SR) and 25 in atrial fibrillation (AF). Radiation dose was compared in a subset of 19 patients with prior retrospective or prospectively triggered CT PV scans without high-pitch. In a subset of 18 patients with prior magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) for PV assessment, PV anatomy and scan duration were compared to high-pitch CT. Using the high-pitch protocol, total effective radiation dose was 1.4 [1.3, 1.9] mSv, with no difference between SR and AF (1.4 vs 1.5 mSv, p=0.22). No high-pitch CT scans were non-diagnostic or had poor IQ. Radiation dose was reduced with high-pitch (1.6 mSv) compared to standard protocols (19.3 mSv, p<0.0001). This radiation dose reduction was seen with SR (1.5 vs 16.7 mSv, p<0.0001) but was more profound with AF (1.9 vs 27.7 mSv, p=0.039). There was excellent agreement of PV anatomy (kappa 0.84, p<0.0001), and a shorter CT scan duration (6 minutes) compared to MRI (41 minutes, p<0.0001).

Conclusions

Using a high-pitch DSCT protocol, PV imaging can be performed with minimal radiation dose, short scan acquisition, and excellent IQ in patients with SR or AF. This protocol highlights the success of new cardiac CT technology to minimize radiation exposure, giving clinicians a new low-dose imaging alternative to assess PV anatomy.

Keywords: arrhythmia (Heart Rhythm Disorders), atrial fibrillation, imaging, pulmonary vein isolation, computed tomography

Introduction

Radiofrequency catheter ablation of the pulmonary veins (PV) is increasingly utilized as an interventional treatment strategy for symptomatic atrial fibrillation (AF).1 However, the pulmonary venous anatomy is variable and suboptimal visualization of the PV may compromise procedural success.2 Hence a detailed knowledge of the left atrial (LA) and pulmonary venous anatomy is imperative for accurate targeting and planning during pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) as well as follow-up for PV stenosis.3–5

Both cardiac computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are non-invasive imaging modalities that are commonly used to visualize the PV and LA anatomy and for co-registration with electroanatomical mapping (EAM) prior to radiofrequency PVI.5 With regards to cardiac CT, exposure to ionizing radiation is of great concern6 and efforts to reduce radiation are essential. New CT technology allows for cardiac imaging with single-beat acquisition and minimal radiation exposure. Second generation 128-slice dual-source CT (DSCT) scanners have improved temporal resolution (~75ms) due to a gantry rotation time of 280ms compared to single source CT.7 Spiral acquisition can also be performed with high pitch (up to 3.4), enabling the entire heart to be scanned within one cardiac cycle and thus drastically reducing the radiation exposure to sub-millisievert values for certain coronary artery examinations.7–8 Pitch is defined as the longitudinal distance that the table travels per revolution of the x-ray tube divided by the total nominal irradiated width of the detector. Higher pitch also reduces acquisition of overlapping slices, which drastically reduces radiation exposure to the patient.

There is a paucity of data on the use of this new CT scanner technology for pulmonary venous imaging. Thus, we aim to determine the radiation dose and assess the adequacy of image quality (IQ) with this prospectively ECG-triggered, high-pitch scan mode using the 128-slice DSCT scanner in patients who are in sinus rhythm (SR) and AF. In addition, we compare the radiation dose and IQ between this high-pitch scan protocol and previously used “standard” retrospective or prospectively ECG-triggered CT protocols. Lastly, we compare the scan duration and PV anatomy between high-pitch CT and MRI.

Methods

Study Population

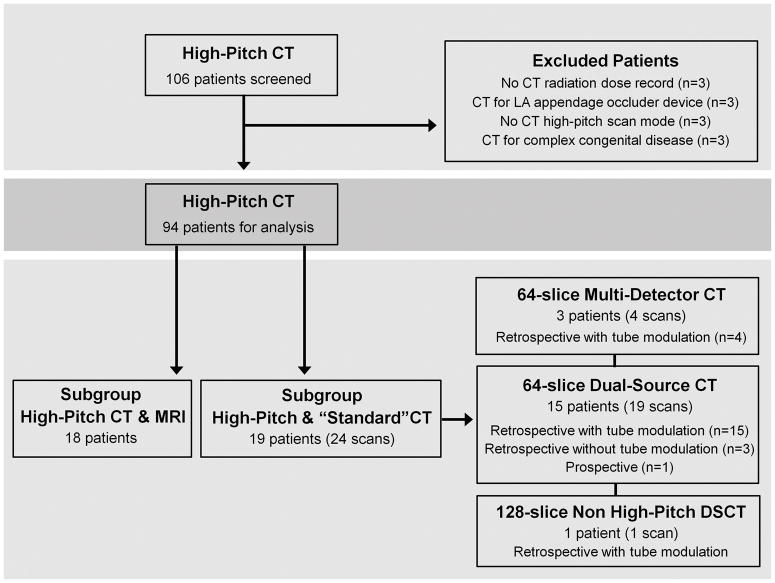

We performed a retrospective query through our radiology database (RENDER, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA) for patients who underwent DSCT evaluation for PV imaging between April 2010 and April 2011 and identified 106 consecutive patients. Figure 1 summarizes the study schema and inclusion/exclusion of patients. A total of 94 patients with a history of paroxysmal or persistent AF who underwent PV imaging with this high-pitch CT protocol were included for analysis. Of the 94 patients, 19 patients had previous standard PV CT scans and 18 patients had a MRI for PV imaging. The local Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of study schema and population.

Imaging Protocols

High-pitch 128-slice DSCT Protocol

All high-pitch CT image acquisition (pitch 3.4) for LA and PV anatomy was performed at end-expiration using a 128-slice DSCT scanner (Definition Flash, Siemens Healthcare, Forchheim, Germany). CT scan parameters include: 2 × 128 × 0.6 mm slice collimation, gantry rotation time of 280ms, half-scan reconstruction for temporal resolution 75 ms, tube voltage of 100 or 120 kV, and effective tube current of 252–456 mAs using automated exposure control. Beta-blocker was not given prior to scanning except in one patient (Metoprolol 5mg intravenously). Oral barium (15 ml) was given in 88% of patients at the request of the referring electrophysiologist. We used a test bolus protocol followed by a contrast-enhanced CT scan with a flow rate of 5–6 ml/s of an iodinated contrast agent and a normal saline chase of 40 ml at the same rate. Scanning was prospectively triggered at 25% of the R-R interval on electrocardiography (ECG) and images were acquired in one heart beat. Patients with hypoattentuation of the LA appendage on the contrast-enhanced CT scan immediately had a delay non-contrast CT scan to evaluate for possible LA appendage thrombus.

Standard CT Protocol

Standard non high-pitch scans (pitch 0.2 – 0.38) were performed at end-expiration using either a 64-slice single-source multi-detector (MDCT) scanner (Siemens Sensation 64, gantry rotation of 330 ms, 32 × 0.6 mm collimation, tube voltage of 120 kVp, effective tube current of 839–862 mAs), 64-slice DSCT scanner (Siemens Definition 64, gantry rotation of 330 ms, 2 × 64 × 0.6 mm collimation, tube voltage of 120 kVp, effective tube current of 158–826 mAs) or 128-slice DSCT scanner (Siemens Definition Flash, gantry rotation of 280 ms, 2 × 128 × 0.6 mm collimation, tube voltage of 100 or 120 kVp, effective tube current of 252–456 mAs) with retrospectively-gated or prospectively-triggered acquisition (Figure 1). Similar to the high-pitch CT protocol, the standard CT protocols included a test bolus scan, followed by contrast-enhanced CT scan, and a delayed non-contrast CT scan if LA appendage thrombus was suspected.

For all high-pitch and standard CT scans, transaxial images were reconstructed with a slice thickness of 0.6 – 1.0 mm and increments of 0.4–0.5 mm. A medium smooth tissue convolution kernel was used. CT image datasets were transferred to an offline workstation (Ziostation, Ziosoft Inc., Redwood City, California) where axial and multiplanar reformatted images of PV and LA anatomy were evaluated.

MRI Protocol

MRI studies were performed using a 1.5 Tesla scanner (Signa HDx, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, Wisconsin) that had an 8-element, phased-array cardiac coil. The MRI protocol was performed with respiratory gating and consisted of 3-plane localizer, sequential 2D steady-state free-precession localizer, and asset calibration. Subsequent hyperventilation sequences included test bolus scan followed by 3D magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) of the pulmonary vessels with administration of intravenous gadolinium (0.1 or 0.2 mmol/kg, depending on renal function). All images were obtained with breath-hold at end-expiration. The 3D MRA was acquired at a slice thickness of 2.2–2.6 mm. From the 3D dataset, multiple volume rendered images and endoluminal views were reconstructed using a dedicated workstation (ADW 4.2, GE Healthcare).

Radiation Dose

For all CT scans, we calculated the effective radiation dose for the PV scan alone and for the total scan, which included the cumulative radiation dose from the topogram, test bolus, contrast-enhanced scan and if performed, the non-contrast delay scan. The effective radiation dose was calculated by multiplying the dose length product (DLP) and a conversion coefficient of 0.014 for the chest.9

Image Quality

Two CT readers, blinded to patients’ clinical data, assessed the CT IQ and PV anatomy by consensus. If there was disagreement, a third CT reader reviewed the images together with the two readers until a consensus was reached (n=4). IQ was assessed based on 5-categories as determined by the presence of artifacts affecting the LA or PV, image noise, and adequate LA and PV contrast enhancement. IQ was classified as 1=excellent, 2=good, 3=moderate, 4=poor, and 5=non-diagnostic or uninterpretable scan. Assessment of artifacts affecting the PV and LA included slab and breathing artifacts, metal or beam hardening artifacts from pacing wires or mechanical valves, and artifacts from barium in the esophagus or stomach.

PV Anatomy

For both the CT and MRI, the PV ostium was defined as the point of inflection between the walls of the PV and LA. 10 The number of separate PV ostia entering the LA was determined in multiple orthogonal planes. On the right, we assessed for the presence of a common, superior, middle, inferior, and “top” PV. On the left, we assessed for the presence of a common, superior, middle, and inferior PV. For LA size, we report the anterior to posterior LA diameter.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous data are presented as mean±SD or median (interquartile range) as appropriate, and percentages for categorical variables. For two group comparisons, we used Student’s t-test or Wilcoxon rank sum test for continuous variables, and Chi-square or Fisher’s Exact test for categorical data, as appropriate. We classified the heart rate analyses into 5 categories using cutpoints defined by the 25th, 50th, 75th and 90th percentiles: <60, 60–70, 71–85, 86–99, ≥100 beats per minute (bpm). We compared the radiation dose across the 5 heart rate categories using Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance. We compared the IQ across the 5 heart rate categories in two ways: (1) those with excellent IQ versus those without using Chi-square test and (2) as differentiated by the ordinal 5-point IQ categories using Fisher’s Exact tests. For the comparison of high-pitch and standard CT protocols, we tested the difference in radiation dose by using mixed effects models to account for the within subject variability. For the subset of patients with CT and MRI, we used a paired t-test to compare the difference in scan duration time. For comparison of PV anatomy between CT and MRI, we reported exact agreement and used Cohen’s Kappa statistics to determine the degree of agreement between the two modalities. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS (Version 9.2, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Baseline patient characteristics for the total cohort who underwent high-pitch scans are summarized in Table 1. Medications listed represent those taken regularly at the time of CT. Baseline renal function was normal, mean left ventricular ejection fraction was preserved and mean LA size was increased in the total cohort, with no difference between SR and AF (all p≥0.06). At the time of CT acquisition, 69 (74%) were in SR. The distribution of heart rates is shown in Figure 2A. The mean total CT scan duration from the beginning of the test bolus to the end of the PV scan was 6±4 minutes, with no difference between patients in SR or AF (p=0.65).

Table 1.

Baseline patient demographics of total cohort and as classified by sinus rhythm or atrial fibrillation.

| Total (n=94) | Sinus (n=69) | AF (n=25) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age (years) | 61±9 | 60±9 | 62±8 | 0.43 |

| Male | 67 (71%) | 49 (71%) | 18 (72%) | 1.00 |

| Caucasian | 91 (97%) | 66 (96%) | 25 (100%) | 0.56 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 30±6 | 30±6 | 31±6 | 0.31 |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 72±18 | 69±16 | 82±22 | 0.01 |

| Risk factors | ||||

| Hypertension | 42 (45%) | 32 (46%) | 10 (40%) | 0.64 |

| Congestive Heart Failure | 22 (23%) | 14 (20%) | 8 (32%) | 0.27 |

| Diabetes Mellitus | 11 (12%) | 8 (12%) | 3 (12%) | 1.00 |

| CVA/TIA | 6 (6%) | 3 (4%) | 3 (12%) | 0.34 |

| CHADS2 score | ||||

| 0 | 35 (37%) | 28 (28%) | 7 (40%) | |

| 1 | 30 (32%) | 20 (29%) | 10 (40%) | 0.37 |

| 2 | 15 (16%) | 11 (16%) | 4 (16%) | |

| 3 | 11 (12%) | 9 (13%) | 2 (8%) | |

| 4 | 3 (3%) | 1 (1%) | 2 (8%) | |

| Medications | ||||

| Warfarin | 89 (95%) | 64 (93%) | 25 (100%) | 0.50 |

| Aspirin | 32 (34%) | 27 (39%) | 5 (20%) | 0.09 |

| Clopidogrel | 4 (4%) | 2 (3%) | 2 (8%) | 0.29 |

| Beta blockers | 62 (70%) | 42 (61%) | 20 (80%) | 0.09 |

| Sotolol | 15 (16%) | 15 (22%) | 0 (0%) | 0.009 |

| Calcium Channel Blocker | 24 (26%) | 18 (26%) | 6 (24%) | 1.00 |

| Amiodarone/Dronedarone/Dofetilide | 21 (22%) | 15 (22%) | 6 (24%) | 0.91 |

| Flecainide/Propafenone | 17 (18%) | 16 (23%) | 1 (4%) | 0.11 |

| Digoxin | 14 (15%) | 8 (12%) | 6 (24%) | 0.19 |

| Devices & Barium | ||||

| Pacemaker/ICD | 16 (17%) | 14 (20%) | 2 (8%) | 0.22 |

| Mechanical Valve | 4 (4%) | 3 (4%) | 1 (4%) | 1.00 |

| Barium | 83 (88%) | 60 (87%) | 23 (92%) | 0.72 |

| Cardiac Parameters | ||||

| Ejection fraction, Echo (%) | 58.0±13.0 | 59.6±12.2 | 53.7±14.2 | 0.06 |

| Left atrial diameter, CT (cm) | 42.6±5.9 | 42.3±6.3 | 43.2±4.8 | 0.58 |

| Laboratory | ||||

| Creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.96±0.20 | 0.95±0.19 | 1.00±0.23 | 0.33 |

| eGFR (ml/min/m2) | 81.9±19.1 | 82.7±18.0 | 79.5±22.3 | 0.48 |

AF denotes atrial fibrillation; BMI, body mass index; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; TIA, transient ischemic attack; ICD, implantable cardiac defibrillator; Echo, echocardiography; CT, computed tomography; and eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate.

Figure 2.

A. Histogram with distribution of heart rates of the 94 patients. B. Radiation dose as classified by heart rate categories (p-value is the result of Kruskal-Wallis test). C. Proportion of the number of patient scans as classified by heart rate categories with excellent, good and moderate image quality using the high-pitch protocol. Note there were no high-pitch scans that were uninterpretable or had poor image quality.

Radiation dose

Table 2 shows the CT scan length, total contrast administered and radiation doses of the high-pitch component as well as the total scan. The median total effective radiation dose of the total scan was 1.4 [1.3, 1.9] mSv, which includes 15 patients who underwent a delay non-contrast scan to further investigate for LA appendage thrombus. There was no difference in the median DLP, volume CT dose index (CTDIvol) or effective radiation dose between patients in SR and AF (all p≥0.22). There was no difference in radiation dose when classified by the five heart rate categories (p=0.78, Figure 2B).

Table 2.

CT parameters of total patient population and as classified by sinus rhythm or atrial fibrillation.

| Total (n=94) | Sinus (n=69) | AF (n=25) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT Features | |||||

| Scan Length (mm) | 195 [184, 210] | 194 [182, 210] | 199 [189, 209] | 0.62 | |

| Total Contrast (ml) | 84.8±11.0 | 85.6±11.4 | 82.6±9.8 | 0.24 | |

| High Pitch Scan | |||||

| Tube Voltage | 100 kV | 80 (85%) | 60 (87%) | 20 (80%) | 0.51 |

| 120 kV | 14 (15%) | 9 (13%) | 5 (20%) | ||

| CTDI vol (mGy) | 3.6 [3.5, 3.6] | 3.6 [3.5, 3.6] | 3.6 [3.5, 3.6] | 0.55 | |

| DLP (mGy × cm) | 88 [81, 97] | 88 [80, 95] | 89 [84, 97] | 0.43 | |

| Effective Dose (mSv) | 1.2 [1.1, 1.4] | 1.2 [1.1, 1.3] | 1.3 [1.2, 1.4] | 0.43 | |

| Total Scan | |||||

| DLP (mGy × cm) | 103 [94, 135] | 103 [92, 122] | 104 [99, 138] | 0.22 | |

| Effective Dose (mSv) | 1.4 [1.3, 1.9] | 1.4 [1.3, 1.7] | 1.5 [1.4, 1.9] | 0.22 | |

Abbreviations as in Table 1. CTDIvol denotes Computed Tomography Dose Index Volume; and DLP, Dose Length Product

When classified by kV, the median effective radiation dose was 1.2 [1.1, 1.3 mSv] for 80 patients scanned with 100 kV and 2.5 [2.2, 2.7] mSv for 14 patients scanned with 120kV (p<0.0001). The mean body mass index [BMI] was 29±5 kg/m2 for patients scanned with 100kV and 34±6 kg/m2 for those scanned with 120 kV.

All 15 delay scans showed no LA appendage thrombus by CT with subsequent confirmation by transesophageal echocardiography. The median effective radiation dose of the 15 delayed scans was 0.6 [0.5, 0.7] mSv.

Image Quality

IQ was assessed as being excellent or good in 93 (99%), and no scans had poor IQ or were non-diagnostic. There was no difference in IQ between patients in SR or AF (p=0.73, Table 3). All 80 patients scanned with 100 kV had good to excellent IQ scans. In the 14 remaining patients who were scanned with 120 kV, 13 had good to excellent IQ and 1 scan was assessed as having moderate IQ due to severe image noise in a patient with BMI of 31 kg/m2 and suboptimal LA contrast enhancement (Figure 3). No scans had slab or breathing artifacts. Artifacts affecting IQ of the LA and PV were predominantly due to barium and beam hardening artifacts. Pacing devices or mechanical valve artifacts affected the LA in 7 (7%) scans, the PV in 8 (9%) scans and both LA and PV in 1 (1%) scan. Of the 30 patients where there was artifact from barium, the barium artifact affected the LA in 19 (20%) patients, PV in 5 (5%) and both in 6 (6%) patients. Regardless of SR or AF, there was no difference in the number of patients affected by metal (p=0.78) or barium artifacts (p=0.6). Image noise level was graded as none to average in the majority of CT scans (n=87, 93%). One (1%) scan was affected by severe noise as mentioned above. Figure 2C depicts the distribution of IQ across the 5 heart rate categories. Across the heart rate categories, there was no difference in the proportion of scans with excellent versus those deemed not excellent in IQ, nor when comparing excellent, good and moderate IQ (both p≥0.28). Of note, the IQ was either excellent or good at high rates (>85 bpm).

Table 3.

CT assessment of image quality and artifacts in the total cohort and as classified by sinus rhythm or atrial fibrillation.

| Total (n=94) | Sinus (n=69) | AF (n=25) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Image Quality | ||||

| Excellent | 59 (63%) | 42 (61%) | 17 (68%) | 0.73 |

| Good | 34 (36%) | 26 (38%) | 8 (32%) | |

| Moderate | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Poor | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Non-diagnostic | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Artifacts | ||||

| Slab | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| Breathing | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | - |

| Metal/Beam Hardening | 16 (17%) | 13 (19%) | 3 (12%) | 0.78 |

| Barium | 30 (32%) | 23 (33%) | 7 (28%) | 0.60 |

| Noise | ||||

| No – average noise | 87 (93%) | 64 (93%) | 23 (92%) | |

| Above average noise | 6 (6%) | 4 (6%) | 2 (8%) | 0.75 |

| Severe noise | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | |

Abbreviations as in Table 1.

Figure 3.

Examples of excellent, good, and moderate image quality from the high-pitch DSCT protocol. CT oblique sagittal and corresponding 3-dimensional volume rendered images showing excellent (A, D), good (B, E), and moderate (C, F) image quality, respectively. Note the absence of breathing or slab artifacts.

High-pitch vs Standard CT Protocols

A subset of 19 patients (59±9 years, BMI 29±5 kg/m2) had a high-pitch scan and a previous standard protocol CT scan for PV anatomy assessment, both of which were clinically indicated at the time. The median duration between high-pitch and standard CT scans was 15.8 months (range 3–52 months). Figure 1 shows the type of CT scanner and protocol used. All 24 standard CT scans were performed with 120 kV. Of the high-pitch scans, 13 (68%) were performed with 100 kV and the remaining 6 scans (32%) with 120 kV.

The median total effective radiation dose was drastically reduced when comparing the standard CT scans to the high-pitch protocol (19.3 [15.1, 25.4] vs 1.6 [1.3, 2.8] mSv, respectively, p<0.0001; Figure 4). Similar differences in radiation dose reduction was seen for patients in SR (standard CT: 16.7 [11.2, 20.5] vs high-pitch scan: 1.5 [1.3, 2.7] mSv, p<0.0001) and even more pronounced in patients with AF (standard CT: 27.7 [21.9, 31.7] vs high-pitch scan: 1.9 [1.4, 2.9] mSv, p=0.039). When comparing radiation dose of scans performed at 120 kV, we found similar marked dose reduction (standard CT: 19.3 [15.1, 25.4] vs high-pitch scan: 2.8 [2.6, 2.9], p=0.01). Only one of the standard CT protocol was performed using a prospectively-triggered, non high-pitch, 120 kV acquisition with a radiation dose of 4.5 mSv (patient was in SR).

Figure 4.

Difference in total effective radiation dose between patients with the high-pitch and standard CT scan protocols, and classified by sinus rhythm and atrial fibrillation (p-values are the results of mixed effect models).

While all high-pitch and 92% of standard CT scans were assessed as having excellent or good IQ, two (8%) scans performed with the standard protocol were assessed to have poor IQ due to large slab artifacts—one in SR (Figure 5) and the other in AF (Figure 6). Additionally, slab artifacts were present in 4 other standard CT scans, however these slab artifacts did not involve the left atrium or PV and thus not graded as severely affecting IQ. Notably, there were no slab or breathing artifacts in the high-pitch subgroup.

Figure 5.

CT oblique sagittal and volume rendered images from a patient who had a previous “standard” retrospective scan on the 64-slice DSCT (A, C) and subsequently a high-pitch 128-DSCT scan (B, D). In both CT scans, the patient was in normal sinus rhythm. Note the slab artifact (arrow) in the retrospective CT scan resulting in a grading of poor image quality but not in the high-pitch scan which was graded as excellent in image quality. The radiation dose was 19.5 mSv for the retrospective scan and 1.2 mSv for the high-pitch scan.

Figure 6.

CT oblique sagittal and volume rendered images from a patient who had a previous “standard” retrospective scan (A, C) and subsequently a high-pitch CT scan (B, D). Both CT scans were performed on the 128-slice DSCT with the patient in atrial fibrillation. Note the slab artifact (arrow) in the retrospective CT scan resulting in a grading of poor image quality but not in the high-pitch scan which was graded as excellent in image quality. The radiation dose was 25 mSv for the retrospective scan and 2.9 mSv for the high-pitch scan.

High-pitch CT vs MRI

When comparing the 18 patients (61±9 years, BMI 30±6 kg/m2) with both CT and MRI, the CT scan duration was strikingly shorter from time of first image acquisition to the final image acquired (CT: 6±1 vs MRI: 41±16 minutes, p<0.0001). The median duration between high-pitch CT and MRI was 24.5 months (range 0.5–102 months).

In total, CT identified 72 PV (right: 38, left: 34) and MRI identified 71 PV (right: 39, left: 32). There was excellent agreement of PV anatomy (presence or absence of each PV) between CT and MRI (kappa 0.84, p<0.0001). There was near perfect agreement between the two modalities when assessing right-sided PV (kappa 0.98, p<0.0001) and good agreement for left-sided PV anatomy (kappa 0.66, p<0.0001). Table 4 shows the excellent agreement between CT and MRI for the assessment of PV anatomy. More specifically, the main discordance between the two modalities was with MRI classifying three left common ostia while CT distinguished these as two separate ostia.

Table 4.

Agreement of pulmonary vein anatomy between high-pitch CT and MRI (n=18 patients).

| Concordance | Discordance | Agreement | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT+/MRI+ | CT−/MRI− | CT+/MRI− | CT−/MRI+ | ||

| Right PV Branch | |||||

| Common | 0 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 100% (18/18) |

| Superior | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100% (18/18) |

| Middle | 2 | 15 | 0 | 1 | 94% (17/18) |

| Inferior | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100% (18/18) |

| Top | 0 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 100% (18/18) |

| Left PV Branch | |||||

| Common | 1 | 13 | 1 | 3 | 78% (14/18) |

| Superior | 13 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 78% (14/18) |

| Middle | 0 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 100% (18/18) |

| Inferior | 13 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 78% (14/18) |

CT denotes computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; and PV, pulmonary vein.

Discussion

CT technology continues to rapidly evolve, especially in the area of reducing radiation dose while preserving IQ. In this study, we employed a high-pitch, ECG-triggered scan mode on a second generation DSCT scanner to assess PV and LA anatomy in patients with SR or AF. Our results show that PV imaging can be performed with a very low median radiation dose of 1.4 mSv and achieves good to excellent CT IQ. CT scanning is feasible with no difference in IQ between patients in AF compared to SR, without the need for heart rate lowering agents. When compared to prior standard CT protocols, we observed a remarkable reduction in radiation dose for both patients with SR and AF with this high-pitch CT protocol. Scan time acquisition was much faster with this low radiation CT scanning technique as compared to MRI, with excellent agreement of PV anatomy between the two imaging modalities.

Thorough assessment of PV and LA anatomy with a non-invasive imaging modality such as CT is important in patients with paroxysmal or persistent AF prior to PVI. Anatomical information from the CT dataset can be integrated into a three dimensional reconstruction of the PV and LA using EAM systems for guidance during radiofrequency PV ablation.5, 11 However, minimizing radiation exposure during CT while maintaining good to excellent IQ is essential. Although CT and EAM integration has been shown to result in reduced procedural duration and radiation exposure11 patients can receive radiation doses of between 15 to 20 mSv from procedural fluoroscopy alone. 12–13 Moreover, recurrence of AF is common and as high as 56% after ablation therapy, repeat procedures are often necessary. 14–15 Hence, minimizing CT radiation dose remains a priority as patients may be further exposed to ionizing radiation during post-procedural follow-up scans and need for repeat ablation procedures, which includes re-imaging the PV anatomy beforehand.

Various CT techniques and modes are available for the imaging of PV anatomy including the use of non-gated and ECG-gating. While non-gated scans historically involve much less radiation than gated scans (4.6 mSv for non-gated scans and 13.4 mSv for gated scans), both may be used for integration with EAM16, though in our experience gated-CT scans have less motion artifact and better IQ. ECG-gated CT scans can be acquired with retrospective gating or prospectively-triggered, at the expense of much higher radiation dose when retrospective gating is employed. 16–17 In our study, the median total radiation dose of the standard CT protocol subgroup was 19.3 mSv which was inclusive of the test bolus, PV scan and delay scans if required and most importantly included patients in SR and AF. If we exclude patients in AF, our median radiation dose with the retrospective gated scans was 16.7 mSv, which is comparable to that reported by Wagner et al. which included only patients in SR.16 Alternatively, prospectively-triggered scanning can also be used to lower radiation dose during CT scan acquisition, 17 as with our one patient who was scanned using the non high-pitch prospective mode with a radiation dose of 4.5 mSv. However, this prospective scan mode is utilized mainly in patients with regular and low heart rates, and in our institution, is no longer implemented for PV imaging since it can be performed with the newer and much lower radiation high-pitch CT protocol.

Non-contrast enhanced prospective ECG-triggered scans using a 64-slice MDCT has also been investigated for its feasibility to accurately assess PV anatomy prior to radiofrequency ablation with low radiation dose of 1.3 mSv.18 However, the CT scan protocol used in the study by Lee et al. was the low-dose non-contrast calcium score scan (which was not used to co-register with EAM) followed by a contrast-enhanced retrospectively-gated CT angiography scan with a mean radiation dose of 8.5 mSv. The non-contrast scans were assessed as having high diagnostic performance for identifying variations in PV when compared to the contrast-enhanced CT scan, and therefore thought as a potential alternative scan mode in patients with renal dysfunction. However, while the 3D-volume rendered reconstructions with the non-contrast CT scans were possible, they were unable to be used to co-register with EAM prior to PVI, thus limiting the clinical utility of non-contrast CT scans in this patient cohort.

Newer CT scanner technology using single-beat acquisition with prospective-triggering can be performed with either > 64-slice MDCT or DSCT scanners.7, 19 The radiation dose for a 320-detector row, single-source CT have yielded low radiation doses for PV imaging of 1.9 mSv for patients with BMI ≤25kg/m2 using 100 kV and 3.8 mSv for patients with BMI >25 kg/m2 using 120 kV.19 When comparing our findings to that of 320-detector row CT with prospective scanning for PV anatomy, our radiation dose for patients scanned at 100kV was lower at 1.2 mSv with the 128-slice DSCT high-pitch protocol despite a higher mean BMI of 29 kg/m2. Similarly, when using 120kV (mean BMI 34kg/m2), CT scanning with the DSCT high-pitch mode resulted in lower radiation dose (2.5 mSv) than that reported with the 320-slice single source scanner. Not only does our study show that this high-pitch DSCT scan mode for imaging of PV anatomy is feasible, this can be achieved with very low radiation dose (median 1.4 mSv). This value is remarkably lower than other previously reported radiation doses for PV imaging without the use of high-pitch scanning.16, 19 To put the radiation dose into perspective, the average annual background radiation amounts to approximately 3 mSv.20 We were able to achieve such low radiation dose because of the high-pitch factor of 3.4 on the second-generation dual-source CT, which allows image acquisition of the entire thorax within one heart beat.

The main issue with poor IQ is the potential for artifacts to adversely affect the co-registration process with EAM. For the high-pitch scans, rate slowing agents were not required for heart rate control in patients with either SR or AF. Regardless of the heart rate or rhythm, we found that IQ was preserved and good to excellent IQ was possible even at overall high heart rates. Notably, since the entire LA and PV ostia are captured within one cardiac cycle on a high-pitch CT scan, slab and breathing artifacts are not present. Interestingly, with the non high-pitch CT scans, we had two cases out of 24 with slab artifacts despite much higher radiation dose (Figures 5–6).

MRI is another option for imaging PV anatomy and has the benefit of not requiring ionizing radiation. However, this imaging modality is time-intensive with a mean total examination time of 48 minutes to complete a PV imaging protocol. 21 In our study, the median total scan duration from the beginning of the test bolus to the end of the CT scan was 6 minutes compared to 41 minutes for MRI, which is an advantage of CT and an important alternative imaging option for patients with claustrophobia, an inability to lie supine for prolonged periods, or those unable to perform long-breath holds due to dyspnea or musculoskeletal issues due to its much shorter scan duration.

Additionally, CT can be performed in patients with cardiac devices, such as pacemakers, defibrillators, or cardiac resynchronization therapy. Metal from device therapy did not adversely affect IQ or the ability to assess PV anatomy on CT. Specifically, 17% of patients in our study had device therapy and underwent CT instead of MRI due to safety concerns, though there are now increasing reports of the safety of MRI in patients with cardiac devices. 22–23

With respect to PV anatomy, we found great agreement between CT and MRI (kappa=0.84), with near perfect agreement for the right sided PV (kappa=0.98). The slight difference between the number of PV between CT and MRI likely reflects the subjective nature of differentiating a short common trunk of a PV from two separate ostia. This discordance between the two modalities may be explained by the better spatial resolution in the z-axis with CT, where images were acquired with a thinner slice thickness of 0.6 to 0.75 mm, in comparison to 2.2 to 2.6 mm with MRI. For this reason, the isotropic spatial resolution of CT provides greater detail of PV anatomy than MRI. Delineating a common ostium correctly is important as it may impact the ablation strategy.

Limitations

The number of patients who had standard CT/MRI for comparison with high-pitch CT scans is small. The choice in PV imaging is dependent on the local expertise and equipment available. CT scans were performed for clinical indications, with variations in PV and LA protocols dictated by individual cardiac CT imagers. However, this reflects real-world practice in a single-tertiary center.

Conclusions

Very low radiation dose (median 1.4 mSv) and good to excellent IQ are achievable with prospectively ECG-triggered, high-pitch DSCT for pulmonary venous imaging in patients with either SR or AF at comparable doses. This radiation dose is drastically lower in comparison to the non high-pitch scan protocol. Scan times are significantly shorter than MRI, with excellent agreement of PV anatomy between the two imaging modalities. This protocol highlights the success of new cardiac CT technology to minimize radiation exposure, giving clinicians a new low-dose imaging alternative to assess PV anatomy.

Acknowledgments

We thank Heather Brown, PhD for her assistance with the CT images. We thank Hang Lee, PhD from the Harvard Catalyst for his statistical guidance. We gratefully acknowledge the clinical services of the Massachusetts General Hospital.

Funding Sources: Dr. Truong received support from NIH grant K23HL098370 and L30HL093896.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr. Truong receives research grant support from Ziosoft, Inc. Dr. Heist receives research grant support and/or honoraria from Biotronik, Boston Scientific, Medtronic, Sorin and St. Jude Medical, and is a consultant to Boston Scientific, Sorin and St. Jude Medical. Dr. Singh receives research grant support, honoraria and is a consultant to St. Jude Medical, Medtronic Inc., Boston Scientific Corp. and Biotronik. He is a consultant to CardioInsight, Thoratec Inc. and Biosense Webster and receives honoraria from Guidant Corp and Sorin Group.

References

- 1.Calkins H, Brugada J, Packer DL, Cappato R, Chen SA, Crijns HJ, Damiano RJ, Jr, Davies DW, Haines DE, Haissaguerre M, Iesaka Y, Jackman W, Jais P, Kottkamp H, Kuck KH, Lindsay BD, Marchlinski FE, McCarthy PM, Mont JL, Morady F, Nademanee K, Natale A, Pappone C, Prystowsky E, Raviele A, Ruskin JN, Shemin RJ. HRS/EHRA/ECAS expert consensus statement on catheter and surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation: recommendations for personnel, policy, procedures and follow-up. A report of the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) Task Force on Catheter and Surgical Ablation of Atrial Fibrillation developed in partnership with the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) and the European Cardiac Arrhythmia Society (ECAS); in collaboration with the American College of Cardiology (ACC), American Heart Association (AHA), and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS). Endorsed and approved by the governing bodies of the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association, the European Cardiac Arrhythmia Society, the European Heart Rhythm Association, the Society of Thoracic Surgeons, and the Heart Rhythm Society. Europace. 2007;9:335–379. doi: 10.1093/europace/eum120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lacomis JM, Goitein O, Deible C, Schwartzman D. CT of the pulmonary veins. J Thorac Imaging. 2007;22:63–76. doi: 10.1097/RTI.0b013e3180317aaf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwartzman D, Lacomis J, Wigginton WG. Characterization of left atrium and distal pulmonary vein morphology using multidimensional computed tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:1349–1357. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(03)00124-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jongbloed MR, Bax JJ, Lamb HJ, Dirksen MS, Zeppenfeld K, van der Wall EE, de Roos A, Schalij MJ. Multislice computed tomography versus intracardiac echocardiography to evaluate the pulmonary veins before radiofrequency catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation: a head-to-head comparison. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:343–350. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tops LF, Bax JJ, Zeppenfeld K, Jongbloed MR, Lamb HJ, van der Wall EE, Schalij MJ. Fusion of multislice computed tomography imaging with three-dimensional electroanatomic mapping to guide radiofrequency catheter ablation procedures. Heart Rhythm. 2005;2:1076–1081. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2005.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hausleiter J, Meyer T, Hermann F, Hadamitzky M, Krebs M, Gerber TC, McCollough C, Martinoff S, Kastrati A, Schomig A, Achenbach S. Estimated radiation dose associated with cardiac CT angiography. JAMA. 2009;301:500–507. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alkadhi H, Stolzmann P, Desbiolles L, Baumueller S, Goetti R, Plass A, Scheffel H, Feuchtner G, Falk V, Marincek B, Leschka S. Low-dose, 128-slice, dual-source CT coronary angiography: accuracy and radiation dose of the high-pitch and the step-and-shoot mode. Heart. 2010;96:933–938. doi: 10.1136/hrt.2009.189100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Achenbach S, Marwan M, Ropers D, Schepis T, Pflederer T, Anders K, Kuettner A, Daniel WG, Uder M, Lell MM. Coronary computed tomography angiography with a consistent dose below 1 mSv using prospectively electrocardiogram-triggered high-pitch spiral acquisition. Eur Heart J. 2010;31:340–346. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christner JA, Kofler JM, McCollough CH. Estimating effective dose for CT using dose-length product compared with using organ doses: consequences of adopting International Commission on Radiological Protection publication 103 or dual-energy scanning. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194:881–889. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.3462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kato R, Lickfett L, Meininger G, Dickfeld T, Wu R, Juang G, Angkeow P, LaCorte J, Bluemke D, Berger R, Halperin HR, Calkins H. Pulmonary vein anatomy in patients undergoing catheter ablation of atrial fibrillation: lessons learned by use of magnetic resonance imaging. Circulation. 2003;107:2004–2010. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000061951.81767.4E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Estner HL, Deisenhofer I, Luik A, Ndrepepa G, von Bary C, Zrenner B, Schmitt C. Electrical isolation of pulmonary veins in patients with atrial fibrillation: reduction of fluoroscopy exposure and procedure duration by the use of a non-fluoroscopic navigation system (NavX) Europace. 2006;8:583–587. doi: 10.1093/europace/eul079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Efstathopoulos EP, Katritsis DG, Kottou S, Kalivas N, Tzanalaridou E, Giazitzoglou E, Korovesis S, Faulkner K. Patient and staff radiation dosimetry during cardiac electrophysiology studies and catheter ablation procedures: a comprehensive analysis. Europace. 2006;8:443–448. doi: 10.1093/europace/eul041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McFadden SL, Mooney RB, Shepherd PH. X-ray dose and associated risks from radiofrequency catheter ablation procedures. Br J Radiol. 2002;75:253–265. doi: 10.1259/bjr.75.891.750253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katritsis D, Wood MA, Giazitzoglou E, Shepard RK, Kourlaba G, Ellenbogen KA. Long-term follow-up after radiofrequency catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation. Europace. 2008;10:419–424. doi: 10.1093/europace/eun018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cappato R, Calkins H, Chen SA, Davies W, Iesaka Y, Kalman J, Kim YH, Klein G, Natale A, Packer D, Skanes A, Ambrogi F, Biganzoli E. Updated worldwide survey on the methods, efficacy, and safety of catheter ablation for human atrial fibrillation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2010;3:32–38. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.109.859116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wagner M, Butler C, Rief M, Beling M, Durmus T, Huppertz A, Voigt A, Baumann G, Hamm B, Lembcke A, Vogtmann T. Comparison of non-gated vs. electrocardiogram-gated 64-detector-row computed tomography for integrated electroanatomic mapping in patients undergoing pulmonary vein isolation. Europace. 2010;12:1090–1097. doi: 10.1093/europace/euq135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hlaihel C, Boussel L, Cochet H, Roch JA, Coulon P, Walker MJ, Douek PC. Dose and image quality comparison between prospectively gated axial and retrospectively gated helical coronary CT angiography. Br J Radiol. 2011;84:51–57. doi: 10.1259/bjr/13222537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee HJ, Kim YJ, Hur J, Nam JE, Hong YJ, Kim HY, Kim HS, Choe KO, Choi BW. Low-dose electrocardiography synchronized nonenhanced computed tomography for assessing left atrium and pulmonary veins before radiofrequency catheter ablation for atrial fibrillation. Am J Cardiol. 2011;108:536–540. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.03.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yang L, Xu L, Yan Z, Yu W, Fan Z, Lv B, Zhang Z. Low dose 320-row CT for left atrium and pulmonary veins imaging-the feasibility study. Eur J Radiol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2011.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gerber TC, Carr JJ, Arai AE, Dixon RL, Ferrari VA, Gomes AS, Heller GV, McCollough CH, McNitt-Gray MF, Mettler FA, Mieres JH, Morin RL, Yester MV. Ionizing radiation in cardiac imaging: a science advisory from the American Heart Association Committee on Cardiac Imaging of the Council on Clinical Cardiology and Committee on Cardiovascular Imaging and Intervention of the Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention. Circulation. 2009;119:1056–1065. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.191650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allgayer C, Zellweger MJ, Sticherling C, Haller S, Weber O, Buser PT, Bremerich J. Optimization of imaging before pulmonary vein isolation by radiofrequency ablation: breath-held ungated versus ECG/breath-gated MRA. Eur Radiol. 2008;18:2879–2884. doi: 10.1007/s00330-008-1070-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dickfeld T, Tian J, Ahmad G, Jimenez A, Turgeman A, Kuk R, Peters M, Saliaris A, Saba M, Shorofsky S, Jeudy J. MRI-Guided ventricular tachycardia ablation: integration of late gadolinium-enhanced 3D scar in patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2011;4:172–184. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.110.958744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nazarian S, Hansford R, Roguin A, Goldsher D, Zviman MM, Lardo AC, Caffo BS, Frick KD, Kraut MA, Kamel IR, Calkins H, Berger RD, Bluemke DA, Halperin HR. A prospective evaluation of a protocol for magnetic resonance imaging of patients with implanted cardiac devices. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:415–424. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-7-201110040-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]