Abstract

Recently, we provided evidence for a possible role of the cardiac proteasome during ischemia, suggesting that a subset of 26S proteasomes is a cell-destructive protease, which is activated as the cellular energy supply declines. Although proteasome inhibition during cold ischemia (CI) reduced injury of ischemic hearts, it remains unknown whether these beneficial effects are maintained throughout reperfusion, and thus, may have pathophysiological relevance. Therefore, we evaluated the effects of epoxomicin (specific proteasome inhibitor) in a rat heterotopic heart transplantation model. Donor hearts were arrested with University of Wisconsin solution (UW) and stored for 12h/24h in 4°C UW ± epoxomicin, followed by transplantation. Efficacy of epoxomicin was confirmed by proteasome peptidase activity measurements and analyses of myocardial ubiquitin pools. After 12hCI, troponin I content of UW was lower with epoxomicin. Although all hearts after 12hCI started beating spontaneously, addition of epoxomicin to UW during CI reduced cardiac edema and preserved the ultrastructural integrity of the post-ischemic cardiomyocyte. After 24hCI in UW ± epoxomicin, hearts did not regain contractility. When hearts were perfused with epoxomicin during cardioplegia, the cardiac proteasome was inhibited immediately, all of these hearts started beating after 24hCI in UW plus epoxomicin and cardiac edema and myocardial ultrastructure were comparable to hearts after 12hCI. Epoxomicin did not affect markers of lipidperoxidation or neutrophil infiltration in post-ischemic hearts. These data further support the concept that proteasome activation during ischemia is of pathophysiological relevance and suggest proteasome inhibition as a promising approach to improve organ preservation strategies.

Keywords: Adenosine-5'-triphosphate, Epoxomicin, heart transplantation, ischemia-reperfusion injury, organ preservation

Introduction

Hypothermic storage in organ preservation solution is the standard method of limiting ischemic damage following organ procurement for transplantation[1]. In human cardiac transplantation, a donor heart can be safely maintained for up to 6h before progressive tissue ischemia limits graft viability[2,3]. Subsequent myocardial reperfusion superimposes oxidative damage and inflammation, and worsens cellar injury that occurs during organ procurement and transplantation[4–6]. To date, the majority of research has focused on reperfusion injury after myocardial ischemia, while molecular events during the ischemic period remain less well characterized.

The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway of protein degradation is the principal non-lysosomal proteolytic system[7] and is thought to contribute to a variety of cardiovascular pathologies, including myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury[8–10]. Recently, we described a possible new mechanism of proteasome mediated ischemic cell injury[11]. We provided evidence that the 26S proteasome is under direct control of the cellular energy status and that a subset of 26S proteasomes is a cell destructive protease, which is activated as the tissue ATP level declines. This led to the implication that a sufficient energy supply prevents the tissue from proteasomal auto-destruction. Accordingly, proteasome inhibition during CI of hearts reduced injury of the ischemic cardiomyocyte[11]. Subsequently, this regulation of the proteasome by ATP has been confirmed in cell culture studies by other investigators [12].

However, it remains unknown whether beneficial effects of proteasome inhibition during myocardial CI are maintained throughout reperfusion, and thus, could be of pathophysiological relevance. Therefore, we hypothesized that proteasome inhibition during hypothermic storage of hearts has beneficial effects throughout reperfusion of the ischemic organs and evaluated the effects of the specific proteasome inhibitor epoxomicin in a syngeneic, heterotopic heart transplantation model in rats.

Materials and Methods

Animal protocol

All procedures were approved by the institutional animal care and use committee. Heterotopic cardiac transplantation was performed in anesthetized (1–2% isofluorane inhalation, Baxter) male Lewis rats (200–250g, Harlan Laboratories), as described[11,13]. Cardioplegic arrest was achieved by aortic injection of 7.5mL of 4°C University of Wisconson solution (UW, Duramed) supplemented with/without 50µM of the specific proteasome inhibitor epoxomicin (Boston Biochem). Explanted hearts were subjected to CI at 4°C in 2.5mL UW supplemented with/without 50µM epoxomicin for 12h or 24h prior to transplantation. Hearts that were transplanted immediately after cardioplegia with UW served as a control group (0hCI). After CI, the UW storage solution was collected and stored at −80°C for further analysis. All animals recovered to normal activity. Hearts which regained spontaneous contractility after transplantation were perfused for 4h until re-cardioplegic arrest with 4°C UW and harvest of the organ. Biopsies from the left ventricle were taken for determination of wet weight to dry weight (W/D) ratios, histology and transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Remaining myocardial tissue was snap frozen in liquid nitrogen for further analyses.

W/D ratios were determined gravimetrically, as described[11,14].

Troponin I enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

UW solutions collected after CI of the hearts were assayed for troponin I using a commercially available ELISA kit (Life Diagnostics) according to manufacturer’s instructions. In the control group, transplantation was performed without CI. Therefore, UW solution was not used for storage of these organs. To serve as a negative control, the arrested hearts were submerged for 1s in 2.5mL of UW to account for contamination of the storage solution with troponin I.

ATP assay

Hearts were homogenized in 1% TCA, centrifuged (2000×g, 10min, 4°C) and supernatants collected. Supernatants were assayed for ATP using a bioluminescence assay (Invitrogen), as described[11,15]. For the calculation of the actual myocardial ATP concentrations, the ATP concentration in extracts prepared from hearts immediately after cardioplegic arrest were considered to equal the normal myocardial ATP concentration of 5mM[16, 17] and the ATP concentrations in hearts after reperfusion were calculated based on the percent of change from normal, as described[11].

Preparation of heart extracts

Proteasome peptidase activity

Proteasome peptidase activities (=total peptidase activity minus activity in the presence of epoxomicin) in myocardial extracts were measured employing the fluorogenic peptide substrate N-Suc-Leu-Leu-Val-Tyr-7-amino-4-methylcoumarin (chymotryptic-like, CT-L, Biomol), as described[11,13]. Reaction mixtures contained ATP at the actual tissue concentration. All enzyme assays were performed immediately after preparation of the cardiac extracts to prevent from proteasome inactivation by freeze-thawing. Enzyme time progression curves showed linearity for 40 min.

Myeloperoxidase (MPO) activity

Myocardial extracts were assayed for MPO activity as a quantifiable marker of polymorphonuclear leukocyte infiltration and neutrophil mediated tissue damage using a commercially available enzyme activity assay kit (Northwest Life Science Specialties) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Lipid peroxidation assay

Malondialdehyde (MDA) in combination with 4-hydroxyalkenals (4-HA) were measured as indicators of lipid peroxidation in the heart extracts using a commercially available colorimetric microplate assay (Oxford Biomedical Research), as described[14].

Western blots

Western blotting with anti-ubiquitin (Sigma) and densitometric quantification of the chemiluminescence signals were performed as described[11,13]. Anti-glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Anti-GAPDH; Applied Biosciences) in combination with HRP labeled anti-mouse (GE Healthcare) were used as control for the protein transfer to the blotting membranes. Chemiluminescence signals were detected with a Chemidoc imaging system and analyzed using the Quantity One gel analyses software (BioRad).

Light microscopy and TEM were performed as described[11]. Images were analyzed by a pathologist (M.M.P.) who was blinded as to the treatment of the hearts.

Statistics

Data are described as mean±S.E.M. Normal distribution was assessed with the Komolgorov-Smirnov test. Because not all data sets passed the normality test (alpha=0.05), the Mann-Whitney U test and the Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance with Dunn’s multiple comparisons test to control for multiple testing were used to compare differences between groups. Fisher's exact test was used for dichotomic categorical variables. Statistical analyses and spline curves were calculated with the GraphPad-Prism program (GraphPad-Software). A two-tailed p<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

All transplanted hearts started to beat spontaneously upon reperfusion after 0hCI and 12hCI in UW, with or without epoxomicin. All of these hearts maintained contractility until organ harvest 4h post transplantation (Tab.1, groups 1–3). After 24hCI in UW, only 1 of 7 hearts regained spontaneous contractility after transplantation, and 0 of 6 hearts after storage in UW plus epoxomicin, respectively (Tab.1, p>0.05, group 4 vs. 5). In contrast, when coronary arteries were perfused with UW plus epoxomicin during organ harvest prior to 24hCI in UW plus epoxomicin, all transplants regained and maintained contractility until harvest after 4h (Tab.1, group 6, p<0.05 vs. groups 4 and 5).

Table 1.

Viability of heart transplants after cold ischemic storage

| Spontaneous contractions after heterotopic heart transplantation |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | CP with | CI in | CI (h) | Yes1 (n) | No (n) |

| 1 | UW | UW | 0 | 6 | 0 |

| 2 | UW | UW | 12 | 6 | 0 |

| 3 | UW | UW/epox | 12 | 6 | 0 |

| 4 | UW | UW | 24 | 1 | 6 |

| 5 | UW | UW/epox | 24 | 0 | 6 |

| 6 | UW/epox | UW/epox | 24 | 6 | 0 * |

CP: Cardioplegia. CI: Cold ischemic storage. UW: University of Wisconsin solution. UW/epox: UW supplemented with 50µM epoxomicin.

All hearts started beating spontaneously after transplantation and maintained contractility until organ harvest after 4h.

p<0.05 vs. groups 4 and 5.

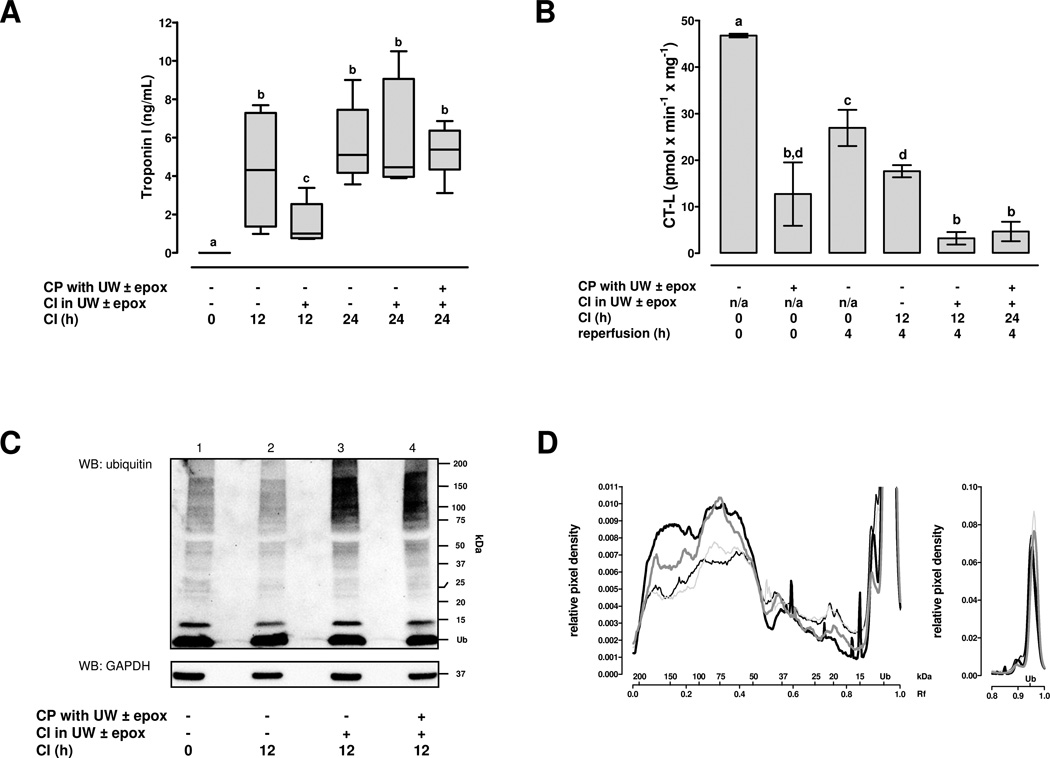

As a surrogate marker of myocardial injury during CI, we quantified troponin I in the preservation solution (Fig.1A). Compared with hearts after 12hCI in UW alone, troponin I content in the storage solution was significantly reduced when UW was supplemented with epoxomicin. Troponin I content in the storage solution after 24hCI was similar among all groups and indistinguishable from the troponin I content after 12hCI in UW alone.

Figure 1.

CP: cardioplegia. CI: cold ischemia. UW: University of Wisconsin solution. epox: epoxomicin, 50µM. A. Troponin I content in the preservation solution after cold ischemic storage of hearts (n=5/group). Boxes extend from the 25th to 75th percentile, the horizontal line shows the median. Error bars show the minimum/maximum. Boxes not sharing the same letter are significantly different (p<0.05). B. Chymotryptic-like proteasome peptidase activities (CT-L) in cardiac extracts. CT-L in extracts from hearts that were not transplanted (reperfusion: 0h) was measured at the normal myocardial ATP concentration (5mM), all other extracts were measured at 1mM ATP (=20% of normal). Mean±SEM, n=5/group. Bars not sharing the same letter are significantly different (p<0.05). C. Representative Western blot (WB) for the detection of free and conjugated ubiquitin in cardiac extracts from beating hearts 4h after transplantation. Top: Membrane probed with anti-ubiquitin. Bottom: Membrane re-probed with anti-GAPDH. Right: Migration positions of protein standards. Lane 1: Control, CP with UW, 0hCI. Lane 2: CP with UW, 12hCI in UW. Lane 3: CP with UW, 12hCI in UW plus epox. Lane 4: CP with UW plus epox, 24hCI in UW plus epox. D. Molecular mass profiles of ubiquitin immunoreactivity in cardiac extracts from 5 independent experiments, as in C. After chemiluminescence detection, pixel densities of each lane were normalized to equal 1. Spline curves were calculated and plotted against the Rf ([distance of protein migration]/[distance of tracking dye migration]) value. Molecular masses were calculated using the Rf values of protein standards. The x-axis shows the Rf value and the corresponding molecular mass (kDa). Ub: Migration position of free ubiquitin. Left: complete molecular mass profile; the y-axis was limited to 0.011 to display the distribution of ubiquitin-protein conjugates. Right: Intensity profile for free ubiquitin. Thin black line: control, CP with UW, 0hCI. Thin grey line: CP with UW, 12hCI in UW. Thick black line: CP with UW, 12hCI in UW plus epox. Thick grey line: CP with UW plus epox, 24hCI in UW plus epox.

To determine whether epoxomicin exposure of the hearts was able to inhibit the myocardial proteasome after cardioplegic arrest and throughout reperfusion after storage in UW, we measured proteasome peptidase activities in the cardiac extracts at the actual tissue ATP concentration. ATP concentrations in reperfused hearts were comparable among all groups (µmol ATP/g wet weight; 0hCI: 0.22±0.02, 12hCI in UW: 0.27±0.04; 12hCI in UW plus epoxomicin: 0.18±0.03; 24hCI in UW plus epoxomicin after cardioplegia with epoxomicin: 0.21±0.03, p>0.05 among the groups) and averaged 20% of the normal myocardial ATP concentration, as determined in extracts from hearts that were prepared immediately after cardioplegic arrest (0.98±0.2 µmol ATP/g wet weight, p<0.05 vs. all other groups). The proteasome CT-L peptidase activities are shown in Fig.1B. Coronary artery perfusion of the hearts with epoxomicin during cardioplegic arrest inhibited myocardial proteasome activities immediately (cardioplegia with UW alone: 46.7±0.4 pmol/mg/h, cardioplegia with UW plus epoxomicin: 12.7±6.8 pmol/mg/h; p<0.05). As compared with hearts after cardioplegic arrest with UW, subsequent transplantation and reperfusion reduced proteasome peptidase activities in the cardiac extracts to 26.9±3.9 pmol/mg/h (p<0.05 vs. hearts after cardioplegia with UW). This inhibition of proteasome peptidase activities in post-ischemic hearts was more pronounced after 12hCI in UW (17.6±1.3 pmol/mg/h, p<0.05 vs. 0h CI in UW). Addition of epoxomicin to UW during 12hCI and 24hCI reduced myocardial proteasome peptidase activities at 4h after transplantation by 70%–80%, as compared with hearts after 12hCI in UW alone.

As a read-out for biological relevant effects of epoxomicin, we analyzed myocardial ubiquitin-protein conjugates in post-ischemic hearts. A typical Western blot with anti-ubiquitin for the analysis of ubiquitin immunoreactivity in the cardiac extracts is shown in Fig.1C and the average molecular mass profiles of ubiquitin immunoreactivity in cardiac extracts from five independent experiments are shown in Fig.1D. After 4h of reperfusion, the intensity of bands corresponding to myocardial high molecular mass ubiquitin-protein conjugates was increased with exposure of hearts to epoxomicin during CI (Fig.1C, lanes 3/4), as compared with control hearts and hearts after 12hCI in UW alone (Fig.1C, lanes 1/2). The molecular mass profiling showed that this shift towards higher amounts of high molecular mass ubiquitin-protein conjugates (>50 kDa) was accompanied by reduced intensities of low molecular mass ubiquitin-protein conjugates (<50 KDa), with no obvious changes in free ubiquitin.

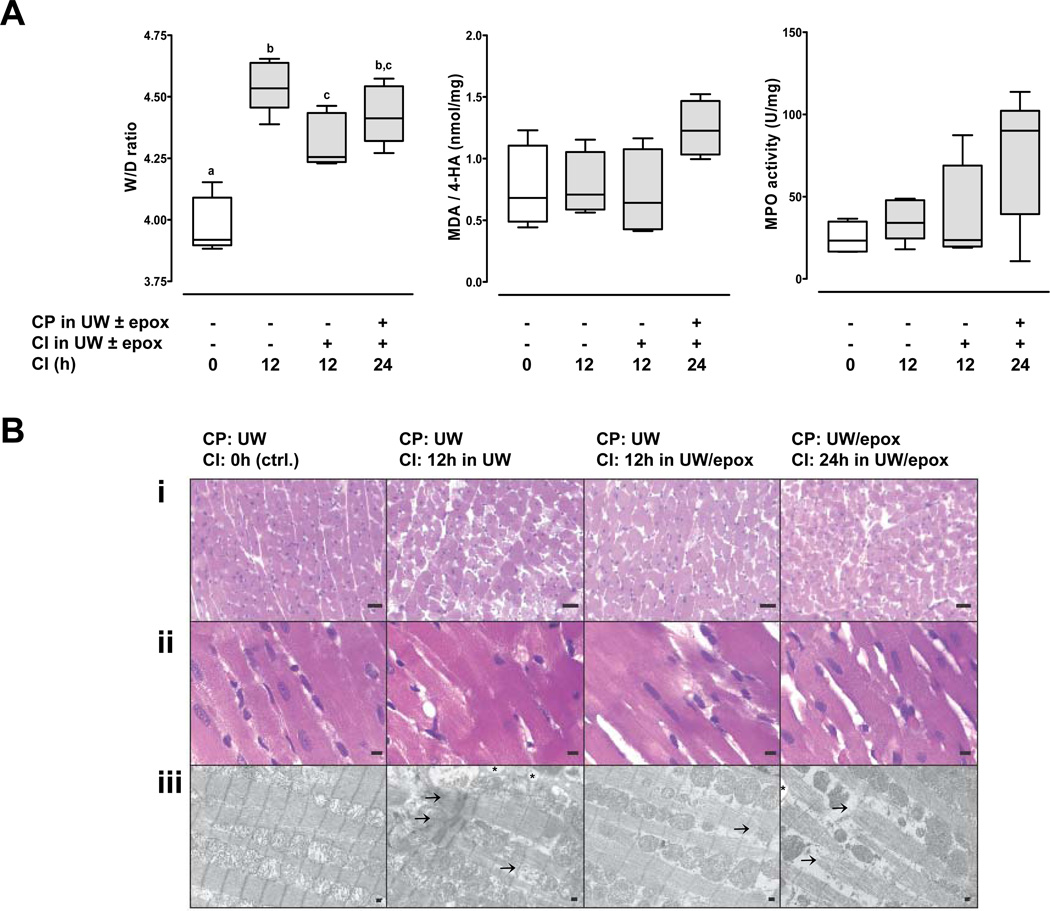

To assess cardiac edema formation, we determined W/D ratios of the beating hearts after 4h of reperfusion (Fig.2A, left). After 12hCI W/D ratios were significantly lower in hearts that were stored in UW plus epoxomicin (W/D ratio: 4.3±0.05), as compared with hearts stored in UW alone (W/D ratio: 4.6±0.05; p<0.05 vs. hearts stored in UW plus epoxomicin). W/D ratios of post-ischemic hearts after cardioplegia with epoxomicin and 24hCI in UW plus epoxomicin were indistinguishable from W/D ratios after 12hCI (W/D ratio: 4.4±0.05).

Figure 2.

CP: cardioplegia. CI: cold ischemia. UW: University of Wisconsin solution. epox: epoxomicin, 50 µM. A. Variables of myocardial injury in beating hearts 4h after transplantation. Boxes extend from the 25th to 75th percentile, the horizontal line shows the median. Error bars show the minimum/maximum. N=5/group. Boxes not sharing the same letter are significantly different (p<0.05). CP: cardioplegia. CI: cold ischemia. UW: University of Wisconsin solution. epox: epoxomicin, 50µM. Left: W/D ratios. Center: MDA/4-HA concentrations. Right: MPO activity. B. Representative photomicrographs of beating hearts 4h after transplantation showing H&E (i.-100×, ii.–400×) and TEM (iii.-6000×). Arrows: disrupted myofibrils. *: vacuolization. Scale bars in A–C represent 50µm, 10µm and 1µm, respectively.

As additional biochemical markers of ischemia-reperfusion injury in the post-ischemic transplants, we measured MDA in combination with 4-HA (Fig.2A, center) and MPO activity (Fig.2A, right) in the heart extracts. Although MDA/4-HA concentrations and MPO activities did not show significant differences among the treatment groups, both parameters were highest after 24hCI.

When compared with control transplanted hearts, reperfused hearts after CI in UW with or without epoxomicin showed increased interstitial edema by light microscopy (Fig.2B, top/center). Furthermore, control transplanted hearts and transplanted hearts after 12hCI in UW plus epoxomicin stained homogeneously, whereas transplanted hearts after 12h in UW alone and after 24hCI in UW plus epoxomicin subsequent to cardioplegia with epoxomicin demonstrated patchy staining. However, these differences were subtle and the various CI conditions could not be differentiated with confidence based on the histomorphology of the hearts. In contrast, TEM demonstrated impairment of the cardiomyocyte ultrastucture of reperfused hearts after 12hCI in UW, as represented by cellular edema, ballooned and disrupted mitochondria, vacuolization and disrupted myofibrils (Fig.2B, bottom). These ultrastructural changes were attenuated in reperfused hearts after 12hCI in UW supplemented with epoxomicin. The ultrastructural appearance of cardiomyocytes in reperfused hearts after cardioplegia with epoxomicin and 24hCI in UW plus epoxomicin was similar to hearts after 12 hCI in UW alone.

Discussion

In the present study we demonstrate that proteasome inhibition during CI of hearts prolongs myocardial viability and reduces reperfusion injury. These findings further support the concept that activation of the 26S proteasome during CI is a pathophysiologically relevant mechanism that contributes to the overall ischemia-reperfusion injury in post ischemic hearts[11]. In addition, our findings have direct implications for human heart transplantation and suggest proteasome inhibition as a promising approach to improve current organ preservation strategies.

It was shown that maintenance of the actual tissue ATP concentration is required for an accurate assessment of proteasome peptidase activities in crude tissue extracts[11,15,18]. Accordingly, we demonstrated that exposure of hearts to epoxomicin during CI suppressed myocardial proteasome activity throughout the reperfusion period. Proteasome inhibition by epoxomicin has been shown to increase cellular levels of high molecular mass ubiquitin-protein conjugates[19]. Thus, our finding that high molecular mass ubiquitin-protein conjugates were increased in extracts from post-ischemic hearts after epoxomicin exposure documents biologically relevant effects of epoxomicin in our model.

We have shown previously that myocardial ATP levels in hearts after cardioplegic arrest decrease during CI with a half-life of 8.2h[11]. Therefore, the determined ATP levels in the hearts after reperfusion suggest that their energy status had not recovered. These findings are consistent with observations during the early reperfusion period after human heart transplantation[20].

Previous studies on myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury reported significantly reduced proteasome peptidase activities in extracts from post-ischemic hearts after 30 – 180 min of warm or cold ischemia[13,21–23], which has been attributed to oxidative damage of proteasome subunits during the reperfusion period[21,24,25]. In the present study, all transplanted hearts were subject to an ischemic period of 40–60 min, which is intrinsic to the surgical procedure and resulted from the time required to complete anastomoses and permit reperfusion. This ischemic period at room temperature explains the finding that proteasome peptidase activities in extracts from control transplanted hearts (0hCI) were already significantly reduced, as compared with extracts that were prepared from hearts immediately after cardioplegic arrest.

Recently, we have shown that proteasome inhibition during CI reduced cellular injury and preserved the ultrastructural integrity of the ischemic cardiomyocyte[11]. The present findings on troponin I content in the preservation solution imply that epoxomicin delayed troponin I leakage from the ischemic hearts, and thus, further confirms our previous observations.

Although all hearts after 12hCI regained and maintained contractility upon reperfusion, proteasome inhibition during CI showed beneficial effects throughout the reperfusion period, as documented by reduced organ edema and improved ultrastucture of the reperfused cardiomyocyte. In contrast, hearts were not viable after 24hCI in UW, irrespective of epoxomicin supplementation. This suggested that either prolonged preservation of hearts through proteasome inhibition is not possible, or that myocardial delivery of epoxomicin through diffusion may not allow fast enough entry into the cardiomyocyte to prevent early ischemic injury. Our findings that all hearts that were perfused with epoxomicin during cardioplegic arrest exhibited immediate inhibition of the proteasome and regained contractility after 24hCI agues in favor of the latter assumption and demonstrates that direct introduction of proteasome inhibitor to the coronary microcirculation affords for maximal cardioprotective effects.

In contrast to the effects of epoxomicin during 12hCI, a true assessment of W/D ratios and cardiomyocyte ultrastucture in reperfused hearts after 24hCI is impossible, because hearts that were not perfused with epoxomicin were not viable. Nevertheless, these parameters suggest organ preservation comparable with transplanted hearts after 12hCI. Although the present study is limited by the lack of quantifiable parameters of myocardial function, the ability to regain and maintain contractility is an indisputable index of myocardial viability. Thus, our findings provide initial evidence that proteasome inhibition prolongs organ viability during CI.

Multiple proteasome inhibitors have been developed and are known to possess profound anti-inflammatory properties[19,26–30]. Proteasome inhibitors have been shown to diminish cellular injury during reperfusion in various organs and tissues, such as brain[31], kidney[32], liver[33] or heart[34]. The majority of these studies attributed beneficial effects of proteasome inhibitors to their anti-inflammatory actions during the reperfusion period. As assessed by MPO/MDA/4-HA measurements in the cardiac extracts, epoxomicin did not influence oxidative or neutrophil mediated cell damage, which occur during the reperfusion period. This observation is consistent with the experimental model, in which the recipient is not systemically exposed to epoxomicin. In addition, this further supports the notion that beneficial effects of proteasome inhibition in the present study are caused by direct cardioprotective effects during the ischemic period.

Taken together, the findings of the present study, in combination with previously reported beneficial effects of proteasome inhibition on cardiac allograft rejection[35], suggest that proteasome inhibitors could be useful during heart transplantation. In addition to well described anti-inflammatory actions of proteasome inhibitors, the present study demonstrates that proteasome inhibition during CI exerts direct and functionally relevant cardioprotective effects. Our results provide physiological relevance for a new mechanism of ischemic tissue injury. This may have implications beyond organ preservation as it is likely applicable to a multitude of pathological situations during which the cellular energy supply decreases.

Acknowledgement

This study was supported in part by grants AHA#0755604B, DFGMA2474/2-2 (both to MM) and NIHT32 GM008750 (to RLG).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Feng S. Donor intervention and organ preservation: where is the science and what are the obstacles? Am J Transplant. 2010;10:1155–1162. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hicks M, Hing A, Gao L, Ryan J, Macdonald PS. Organ preservation. Methods Mol Biol. 2006;333:331–374. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-049-9:331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Patel J, Kobashigawa JA. Cardiac transplantation: the alternate list and expansion of the donor pool. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2004;19:162–165. doi: 10.1097/00001573-200403000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forman MB, Puett DW, Virmani R. Endothelial and myocardial injury during ischemia and reperfusion: pathogenesis and therapeutic implications. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1989;13:450–459. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(89)90526-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Richard VJ, Murry CE, Jennings RB, Reimer KA. Oxygen-derived free radicals and postischemic myocardial reperfusion: therapeutic implications. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 1990;4:85–103. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-8206.1990.tb01019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tsao PS, Aoki N, Lefer DJ, Johnson G, 3rd, Lefer AM. Time course of endothelial dysfunction and myocardial injury during myocardial ischemia and reperfusion in the cat. Circulation. 1990;82:1402–1412. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.82.4.1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hershko A, Ciechanover A. The ubiquitin system. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:425–479. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yu X, Kem DC. Proteasome inhibition during myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;85:312–320. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Willis MS, Townley-Tilson WH, Kang EY, Homeister JW, Patterson C. Sent to destroy: the ubiquitin proteasome system regulates cell signaling and protein quality control in cardiovascular development and disease. Circ Res. 2010;106:463–478. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.208801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsukamoto O, Minamino T, Kitakaze M. Functional alterations of cardiac proteasomes under physiological and pathological conditions. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;85:339–346. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geng Q, Romero J, Saini V, Baker TA, Picken MM, Gamelli RL, Majetschak M. A subset of 26S proteasomes is activated at critically low ATP concentrations and contributes to myocardial injury during cold ischemia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2009;390:1136–1141. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2009.10.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang H, Zhang X, Li S, Liu N, Lian W, McDowell E, Zhou P, Zhao C, Guo H, Zhang C, Yang C, Wen G, Dong X, Lu L, Ma N, Dong W, Dou QP, Wang X, Liu J. Physiological levels of ATP negatively regulate proteasome function. Cell Res. 2010 Aug 31; doi: 10.1038/cr.2010.123. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Majetschak M, Patel MB, Sorell LT, Liotta C, Li S, Pham SM. Cardiac proteasome dysfunction during cold ischemic storage and reperfusion in a murine heart transplantation model. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;365:882–888. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.11.092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garcia-Covarrubias L, Manning EW, 3rd, Sorell LT, Pham SM, Majetschak M. Ubiquitin enhances the Th2 cytokine response and attenuates ischemia-reperfusion injury in the lung. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:979–982. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0B013E318164E417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Majetschak M, Sorell LT. Immunological methods to quantify and characterize proteasome complexes: development and application. J Immunol Methods. 2008;334:91–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2008.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Beer M, Seyfarth T, Sandstede J, Landschutz W, Lipke C, Kostler H, von Kienlin M, Harre K, Hahn D, Neubauer S. Absolute concentrations of high-energy phosphate metabolites in normal, hypertrophied, and failing human myocardium measured noninvasively with (31)P-SLOOP magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;40:1267–1274. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02160-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kostler H, Landschutz W, Koeppe S, Seyfarth T, Lipke C, Sandstede J, Spindler M, von Kienlin M, Hahn D, Beer M. Age and gender dependence of human cardiac phosphorus metabolites determined by SLOOP 31P MR spectroscopy. Magn Reson Med. 2006;56:907–911. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Powell SR, Davies KJ, Divald A. Optimal determination of heart tissue 26S-proteasome activity requires maximal stimulating ATP concentrations. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;42:265–269. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meng L, Mohan R, Kwok BH, Elofsson M, Sin N, Crews CM. Epoxomicin, a potent and selective proteasome inhibitor, exhibits in vivo antiinflammatory activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:10403–10408. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.18.10403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smolenski RT, Lachno DR, Yacoub MH. Adenine nucleotide catabolism in human myocardium during heart and heart-lung transplantation. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1992;6:25–30. doi: 10.1016/1010-7940(92)90094-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bulteau AL, Lundberg KC, Humphries KM, Sadek HA, Szweda PA, Friguet B, Szweda LI. Oxidative modification and inactivation of the proteasome during coronary occlusion/reperfusion. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:30057–30063. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100142200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Das S, Powell SR, Wang P, Divald A, Nesaretnam K, Tosaki A, Cordis GA, Maulik N, Das DK. Cardioprotection with palm tocotrienol: antioxidant activity of tocotrienol is linked with its ability to stabilize proteasomes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H361–H367. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01285.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Powell SR, Wang P, Katzeff H, Shringarpure R, Teoh C, Khaliulin I, Das DK, Davies KJ, Schwalb H. Oxidized and ubiquitinated proteins may predict recovery of postischemic cardiac function: essential role of the proteasome. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2005;7:538–546. doi: 10.1089/ars.2005.7.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farout L, Mary J, Vinh J, Szweda LI, Friguet B. Inactivation of the proteasome by 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal is site specific and dependant on 20S proteasome subtypes. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2006;453:135–142. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2006.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Divald A, Kivity S, Wang P, Hochhauser E, Roberts B, Teichberg S, Gomes AV, Powell SR. Myocardial ischemic preconditioning preserves postischemic function of the 26S proteasome through diminished oxidative damage to 19S regulatory particle subunits. Circ Res. 2010;106:1829–1838. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.219485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Groll M, Huber R. Inhibitors of the eukaryotic 20S proteasome core particle: a structural approach. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1695:33–44. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2004.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moore BS, Eustaquio AS, McGlinchey RP. Advances in and applications of proteasome inhibitors. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2008;12:434–440. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.06.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McConkey DJ, Zhu K. Mechanisms of proteasome inhibitor action and resistance in cancer. Drug Resist Updat. 2008;11:164–179. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kisselev AF, Goldberg AL. Proteasome inhibitors: from research tools to drug candidates. Chem Biol. 2001;8:739–758. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(01)00056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guedat P, Colland F. Patented small molecule inhibitors in the ubiquitin proteasome system. BMC Biochem. 2007;8(Suppl 1):S14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2091-8-S1-S14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Phillips JB, Williams AJ, Adams J, Elliott PJ, Tortella FC. Proteasome inhibitor PS519 reduces infarction and attenuates leukocyte infiltration in a rat model of focal cerebral ischemia. Stroke. 2000;31:1686–1693. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.7.1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takaoka M, Itoh M, Kohyama S, Shibata A, Ohkita M, Matsumura Y. Proteasome inhibition attenuates renal endothelin-1 production and the development of ischemic acute renal failure in rats. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2000;36:S225–S227. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200036051-00067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alexandrova A, Petrov L, Georgieva A, Kessiova M, Tzvetanova E, Kirkova M, Kukan M. Effect of MG132 on proteasome activity and prooxidant/antioxidant status of rat liver subjected to ischemia/reperfusion injury. Hepatol Res. 2008;38:393–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2007.00270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Campbell B, Adams J, Shin YK, Lefer AM. Cardioprotective effects of a novel proteasome inhibitor following ischemia and reperfusion in the isolated perfused rat heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 1999;31:467–476. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.1998.0880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luo H, Wu Y, Qi S, Wan X, Chen H, Wu J. A proteasome inhibitor effectively prevents mouse heart allograft rejection. Transplantation. 2001;72:196–202. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200107270-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]