Abstract

Cognitive neuroscientists study how the brain implements particular cognitive processes such as perception, learning, and decision-making. Traditional approaches in which experiments are designed to target a specific cognitive process have been supplemented by two recent innovations. First, formal models of cognition can decompose observed behavioral data into multiple latent cognitive processes, allowing brain measurements to be associated with a particular cognitive process more precisely and more confidently. Second, cognitive neuroscience can provide additional data to inform the development of cognitive models, providing greater constraint than behavioral data alone. We argue that these fields are mutually dependent: not only can models guide neuroscientific endeavors, but understanding neural mechanisms can provide critical insights into formal models of cognition.

Introduction

The past decade has seen the emergence of a multidisciplinary field: model-based cognitive neuroscience [1–6]. This field uses formal cognitive models as tools to isolate and quantify the latent cognitive processes of interest in order for them to be associated to brain measurements more effectively. At the same time, this emerging field also uses brain measurements such as single-unit electrophysiology, magneto/electroencephalography (MEG, EEG), and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to address questions about cognitive models that cannot be addressed from within the cognitive models themselves.

Figure 1 presents a schematic overview of the relation between three different fields that all study human cognition: experimental psychology, mathematical psychology, and cognitive neuroscience. These disciplines share the common goal of drawing conclusions about cognitive process, but each branch has a distinct approach: experimental psychologists focus on behavioral data, mathematical psychologists focus on formal models, and cognitive neuroscientists focus on brain measurements. The figure also illustrates how the “model-in-the-middle” approach [1] can unify these separate disciplines by using a formal model as the pivotal element to bridge behavioral data and brain measurements with latent cognitive processes.

Figure 1.

The “model-in-the-middle” paradigm [1]unifies three different scientific disciplines. The horizontal dashed arrow symbolizes experimental psychology, a field that studies cognitive processes using behavioral data; the diagonal dotted arrows symbolize the field of cognitive neuroscience, a field that studies cognitive processes using brain measurements and constraints from behavioral data; the top two solid arrows symbolize the field of mathematical psychology, a field that studies cognitive processes using formal models of cognitive processes constrained by behavioral data (see also box 1). The bi-directional red arrow symbolizes the symbiotic relationship between formal modeling and cognitive neuroscience and is the focus of this review (see also Box 3).

This review focuses on one particular element of the “model-in-the-middle” approach: the symbiotic relationship between cognitive modeling and cognitive neuroscience (Figure 1, red arrow). We begin by outlining the benefit of using formal cognitive models to guide the interpretation of neurophysiological data, a practice that has a relatively long history in vision sciences (e.g., [7–9]), but one that is becoming commonly used to formulate linking propositions of increasing complexity. We then discuss the equally important issue of using neurophysiological data to inspire and constrain cognitive models, a practice that is particularly critical when competing cognitive models cannot be discriminated solely on the basis of behavioral data (e.g., [10]). We conclude that the symbiotic relationship between cognitive modeling and cognitive neuroscience results in palpable progress towards the shared goal of better understanding the functional architecture of human cognition. Specifically, this symbiotic relationship will accelerate the search for mechanistic explanations of cognitive processes and will discourage the assignment of cognitive functions to particular neural substrates without first attempting to disentangle the myriad operations that underlie a single behavioral output measurement like response time (RT) or accuracy.

How cognitive models inform cognitive neuroscience

Before any particular cognitive model is applied in scientific practice, it must be subjected to several sanity checks in order to provisionally conclude that the model parameters are reliable and veridical reflections of hypothesized latent cognitive process (see Box 1). After validation, the cognitive model can be used to inform cognitive neuroscience in several ways.

Box 1. How to confirm that your cognitive model is valid.

The symbiotic relationship between cognitive models and cognitive neuroscience hinges on whether the cognitive models are valid: useful inferences can only be drawn if the model parameters faithfully represent the associated cognitive processes. The validity of a cognitive model can be tested in several closely related ways (Figure 2). First, the model needs to fit the behavioral data reasonably well. A model that fails to fit the data is probably misspecified, and as a result the estimated parameters cannot be assumed to measure accurately the corresponding cognitive processes.

Second, the model needs to fit the behavioral data with relatively few degrees of freedom; this usually means that parameters are constrained across experimental conditions in a meaningful way. For instance, when participants are told to respond quickly in one condition and accurately in another then it is desirable if a good fit is obtained with only a response caution parameter free to vary between the two conditions.

Third, the model parameters need to correspond to the hypothesized cognitive processes. This is a key aspect of a model’s validity, and it is usually assessed with a test of specific influence [37]. For instance, the diffusion model for response times and accuracy (e.g., [41]) proposes that observed behavior in speeded two-choice tasks can be decomposed in several cognitive processes such as response caution and speed of information processing. One test of specific influence entails that the model is fit to data that feature stimuli of varying difficulty. The test of selective influence is successful if drift rate is the only parameter that changes as a function of task difficulty.

Fourth, parameter recovery simulation studies need to confirm that the model is well identified. When a model contains many parameters and the observed data are sparse, there is no guarantee that the parameter estimates are reliable. When simulation studies show that the parameters with which synthetic data were generated cannot be recovered, this suggests that either the model needs to be simplified (i.e., parameters need to be eliminated) or additional data need to be collected (e.g., [42]). The above concerns are often ignored and their importance is particularly pressing for models that are newly developed.

First, cognitive models decompose observed behavior into constituent cognitive components and thereby provide predictors that allow researchers to focus more precisely on the process of interest and attenuate to the impact of nuisance processes (e.g., [11]). In this capacity, cognitive models help enhance sensitivity for detecting partially latent and uncorrelated factors in neuroscience data, thereby allowing more specific inferences. For instance, the Linear Ballistic Accumulator model (LBA; [12]) decomposes response choice and response times into meaningful cognitive concepts such as the time needed for peripheral processes (e.g., encoding the stimulus, executing the motor response), response caution, and speed of information processing (see Box 2 for details). We exploited this model-based decomposition in a recent experiment on the neural mechanisms of response bias [13]; see also [14]. In our experiment, participants had to decide quickly whether a random dot kinematogram was moving leftward or rightward (e.g., [15]). Before stimulus onset, a cue provided probabilistic information about the upcoming stimulus direction, intended to bias the participant’s decision – for instance, the cue “L9” indicated that the upcoming stimulus was 90% certain to move to the left. The behavioral data confirmed that prior information biased the decision process: actions consistent with the cue were executed quickly and accurately, and actions inconsistent with the cue were executed slowly and inaccurately. The LBA model accounted for these data by changing only the balance between the response caution parameters for the competing accumulators. Despite the fact that the cue-induced bias was clearly visible in the behavioral data and the model fits, the fMRI data did not reveal any reliable cue-induced activation. However, the inclusion of the LBA bias parameter as a covariate in the regression equation revealed cue-related activation in regions that mostly match theoretical predictions (such as the putamen, orbitofrontal cortex, and hippocampus). This result suggests that the human brain uses prior information by increasing cortico-striatal activation to selectively disinhibit preferred responses. More generally, this example highlights the practical benefits of using a formal model to simultaneously increase the specificity of inferences made about underlying cognitive processes and the sensitivity of neurophysiological measurements.

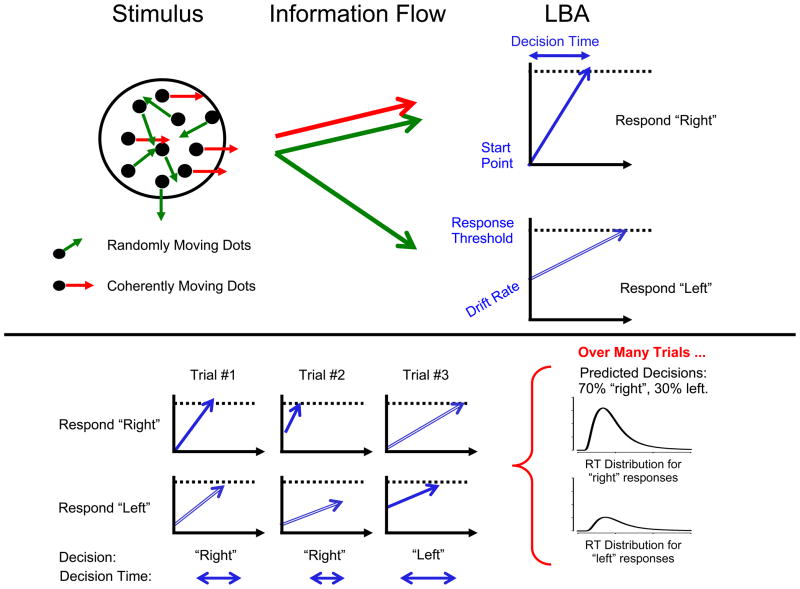

Box 2. The Linear Ballistic Accumulator model.

A random dot kintematogram consists of many dots moving in random directions, and a few dots moving coherently. The observer’s task is to decide whether the coherent motion is rightward (as in the example in Figure 3) or leftward (which occurs on other trials). The linear ballistic accumulator [12] represents this decision as a race between two accumulators: one for the response “left” and one for the response “right”. The accumulators race towards response thresholds (dashed black lines), and the first accumulator to reach the threshold determines the response. In the figure, the racing accumulation processes are shown by the blue arrows: the filled blue arrow represents the accumulator that ultimately wins the race, and triggers the decision, the unfilled arrow represents the accumulator for the alternative response. The predicted response time is just the time taken to reach threshold (“decision time”) plus some time for processes before and after the decision process (such as stimulus perception and response execution).

The accumulators begin their race from start points that are sampled independently and randomly across trials. The speed of accumulation is termed the “drift rate”. The drift rate for each accumulator includes some trial-to-trial randomness, but is also systematically influenced by information extracted from the stimulus. In the example, the randomly-moving dots in the stimulus equally support both responses - because some move left, and others move right - and so these dots influence the drift rates in both accumulators (long green arrows). The coherently-moving dots only support one response, so they only influence drift rate in one accumulator (long red arrow). For this reason, the drift rate in the accumulator corresponding to the correct response (“right” in the example) will usually be faster than the drift rate corresponding to the wrong response.

The two accumulators are sometimes given different response thresholds or start point, to represent a priori decision bias (e.g., a preference for the “left” response over the “right” response).

Second, cognitive models allow researchers to identify the latent process that is affected by their experimental manipulation, either in a confirmatory or exploratory fashion. For instance, Sevy et al. (2006)[16] used the Expectancy-Valence model for the Iowa gambling task (e.g., [17]); this task is complex and likely involves many cognitive operations that are often not explicitly dissociated when neurophysiological measurements are recorded. However, the application of a formal model allowed the task to be decomposed into separable latent variables, permitting Yechiam et al. to argue that a reduction in dopaminergic activity selectively increased the model’s recency parameter. This finding reveals substantially more than the general statement that dopaminergic depletion impairs overall performance and instead specifically supports the hypothesis that low dopaminergic activity enhances attention to recent outcomes at the expense of outcomes obtained in the more distant past.

Third, cognitive models can be used to associate patterns of brain activation with individual differences in cognitive processes of interest. For instance, in an fMRI experiment on the speed-accuracy trade-off, Forstmann et al. (2008)[18] found that instructions to respond quickly result in focused activation of the right anterior striatum and the right pre-supplementary motor area (pre-SMA). Application of the LBA model to the behavioral data revealed that the effect of speed instruction was to selectively lower the LBA response caution parameter. However, speed instructions affected some participants more than others, and those participants who had a relatively large decrease in LBA-estimated response caution also had a relatively large increase in activation for the right anterior striatum and right pre-SMA. This example illustrates how an individual difference analysis can increase confidence in the association between a particular cognitive process and the activation in a specific brain network (see also [19]).

Fourth, cognitive models can directly drive the principled search for brain areas associated with a proposed cognitive function. This approach has been successfully used in the field of reinforcement learning, which is arguably the origin of model-based cognitive neuroscience (e.g., [2, 6, 20]). In fMRI research, this means that a formal cognitive model is designed to make predictions that are then convolved with the hemodynamic response function. Next, the predicted BOLD response profiles are used to search for brain areas with an activation profile that is qualitatively or quantitatively similar. For instance, Noppeney et al. (2010)[21] used the compatibility bias model for the Eriksen flanker task [22] to generate predicted BOLD response profiles to locate a brain region involved in the accumulation of audiovisual evidence. A similar but more confirmatory approach was taken by Borst et al. (2010)[23], who used the ACT-R model to predict hemodynamic responses in five brain regions, with each region corresponding to a cognitive resource in the model (see also [24–26]).

In sum, there are many ways in which cognitive models have informed cognitive neuroscience. There is no standard procedure and the single best way to proceed depends on the model, the brain measurement technique, and the substantive research question. Although the above examples focused primarily on fMRI studies, the general principles apply regardless of the specific measurement technique (e.g., see [27]), for an application involving EEG), and can be used to gain insight into the relationship between latent processes and neural mechanisms on both a within- and between-subject basis (Box 3).

Box 3. Case study.

The subjective value of a stimulus has long been known to bias behavioral choice, and neurophysiological investigations over the last decade suggest that value directly modulates the operation of the sensorimotor neurons that are guide motor interactions with the environment. Following the approaches employed by these early single-unit recording studies, Serences used a combination of linear-non-linear-Poisson (LNP) models [43–45] and logistic regression models [46–47] to show that the subjective value of a stimulus also modulates neural activation in areas of early visual cortex (V1, V2, etc.) that are typically thought to play a primary role in representing basic low-level sensory features (as opposed to regions more directly involved in mediating motor responses). The implication of this observation is that reward not only influences late-stage response thresholding mechanisms, but also the quality of the sensory evidence being accumulated during decision making (e.g., the drift rate, see Box 2).

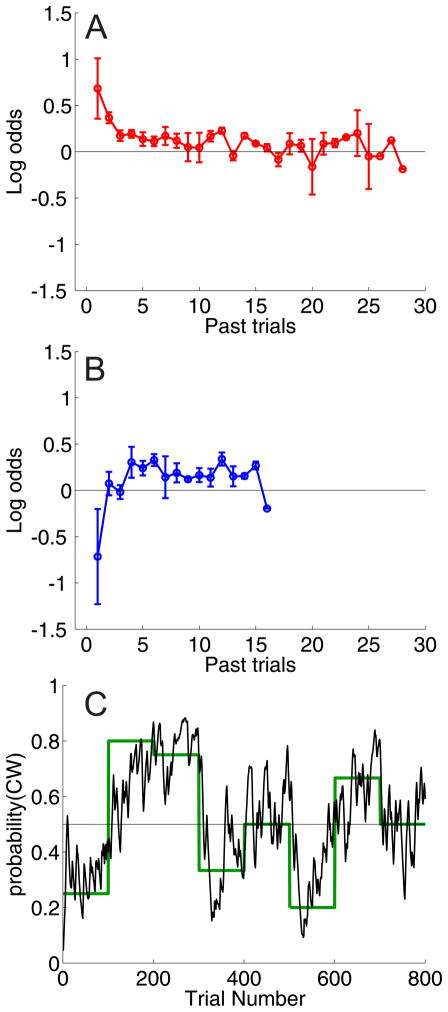

More importantly, however, the computational models that were employed provided trial-by-trial estimates of the subjective (and latent) value assigned to each of two stochastically rewarded choice alternatives based on the prior reward and prior choice history of each option (Figure 4). These trial-by-trial estimates open up a number of analysis alternatives ranging from the within-subject sorting of trials into several discrete bins based on the subjective value of the selected alternative (e.g., [43, 45]), to evaluating the continuous mapping between value and neural responses. This ability is critical because there is considerable variability in the strategies employed by individual subjects (see e.g., [47]), so within-subject estimates are inherently more sensitive than simply comparing the value of two stimulus classes on a between-subject basis. For example, some subjects heavily weight recent rewards while disregarding past rewards, and thus are fast to adapt to transitions in reward probability at the expense of choice stability. On the other hand, other subjects employ a much longer integration window that trades-off improved stability for decreased flexibility to adapt as reward ratios change over time. These formal models may thus provide a powerful tool to classify reward sensitivity (or any other potential cognitive factor of interest) on a within-subject basis, thereby opening up many new avenues of clinical inquiry. For example, a predilection for overweighting distal rewards might be associated with extreme anxiety, whereas a predilection for overweighting recent rewards might be associated with impulsivity and addiction. These individual hypotheses clearly need further exploration, but the use of relatively simple computational models to reveal how individuals respond to stochastic changes in the reward structure of their environment may prove to be a powerful tool for gaining insights into both normal and abnormal decision mechanisms.

How cognitive neuroscience informs cognitive models

Up until a few years ago, neurophysiological data played a very modest role in constraining cognitive models and guiding their development (with the exception of neurocomputational models specifically designed to account for neural data: e.g., [28–29]). One example of a prominent cognitive model that has undergone a transformation as a result of neuroscience data is ACT-R (e.g., [24–26]), which now associates particular brain areas with separate cognitive modules, thus placing severe constraints on the model. For instance, when a task evokes activity in a certain area of posterior parietal cortex this constrains ACT-R to employ the “imaginal module” to account simultaneously for observed behavior and the BOLD response. In addition, the specific subdivision of cognitive modules in ACT-R was informed by the neuroscience data ([24–26], p. 142).

In general, brain measurements can be viewed as another variable to constrain a model or select between competing models that could not otherwise have been distinguished [6]. For instance, two competing models may have fundamentally different information processing dynamics but nonetheless generate almost identical predictions for observed behavior. When brain measurements can be plausibly linked to the underlying dynamics, this provides a powerful way to adjudicate competing models. We illustrate this approach with three closely related examples.

A first example comes from Churchland et al. (2008)[30], who studied multi-alternative decision making in monkeys using single-cell recordings. Monkeys performed a random dot discrimination task (Box 2) with either two or four response alternatives. Mathematical models of multi-alternative decision making such as the LBA (Box 2) often assume that when the number of choice alternatives increases, participants compensate for the concomitant increase in task difficulty by increasing their response caution, that is, by increasing the distance from starting point to response threshold (e.g., [31]). Although these models predict increased separation between start point and response threshold, behavioral data cannot discriminate between a decrease in starting point and an increase in response threshold as these mechanisms are conceptually distinct but mathematically equivalent. The results from Churchland et al., however, support the decrease-in-starting point account and not the increase-in-threshold account: in the four-alternative task, neural firing rates in the lateral intraparietal area started at a relatively low level but finished at a level that was the same as in the two-alternative task.

A second example comes from Ditterich (2010)[10], who compared a range of formal models for multi-alternative perceptual decision making. All of the models integrated noisy information over time until threshold, but they differed in many other important aspects: integration was done with and without leakage, competition between accumulators was accomplished by feedforward or feedback inhibition, and accumulator output was combined across alternatives by linear or nonlinear mechanisms. After fitting the models to data, Ditterich (2010, p. 12) concluded that “it seems to be virtually impossible to discriminate between these different options based on the behavioral data alone”. However, this does not mean that the models cannot be discriminated at all. In fact, Ditterich (2010) demonstrated that the internal dynamics of the models have unique signatures that could be distinguished in principle using neurophysiological data (e.g., [30]).

A third example comes from Purcell et al. (2010)[32] who used a speeded visual search task in which monkeys were required to make an eye movement toward a single target presented among seven distractors. Purcell et al. measured single-cell firing rates in visual and movement neurons from frontal eye field in an attempt to distinguish various accumulator models for evidence integration and decision. Constraint for the models was gained by using the neural data (spike rates) as inputs for the cognitive models (to drive the accumulators to threshold). A crucial aspect of this procedure is that the models must determine the point in time where the accumulators start to be driven by the stimulus, as prior to stimulus onset neural activity is dominated by random noise and is best ignored. For this reason, all models with perfect integration failed, as they were overly impacted by early spiking activity that was unrelated to the stimulus. However, two classes of models were able to account for the behavioral data: leaky integration models effectively attenuate the persistent influence of early noise inputs, and gated integration models block the influence of noise inputs until a certain threshold level of activation has been reached. Once again, behavioral data alone could not distinguish between these competing accounts. However, this model mimicry was resolved by evaluating empirical data collected from movement neurons during the decision making task. Models with leaky integration failed to account for the detailed dynamics in the movement neurons, whereas models with gated integration accounted for these neurophysiological data with impressive precision.

These three case studies highlight the notion that data from cognitive neuroscience can constrain models aimed at characterizing the cognitive architecture of human information processing. This is also the virtue of the cognitive models themselves; the detailed predictions about underlying dynamics that follow from a valid and well-specified model allow competing accounts to be critically tested given the appropriate constraints – and these constraints may increasingly come in the form of neurophysiological data. The major limitation of this mutually constraining synthesis, and a major challenge for future research, is to further validate linking hypotheses between neural activity in a particular brain region and behavior. For instance, are the neural generators that govern behavioural output in a visual 2AFC task adequately characterized by the spiking activity in LIP or FEF? Certainly a great deal of evidence supports this conclusion [15, 32], but important functional properties that only emerge when examining systems-level neural dynamics may be missed, and these emergent properties may require a re-evaluation of existing linking hypotheses between neural activity and cognition.

Conclusion and outlook

Model-based cognitive neuroscience is an exciting new field that unifies several disciplines that have traditionally operated in relative isolation (Figure 1). We have illustrated how cognitive models can help cognitive neuroscience reach conclusions that are more informative about the cognitive process under study, and we have shown how cognitive neuroscience can help distinguish between cognitive models that provide almost identical predictions for behavioral data.

Within the field of model-based cognitive neuroscience, new trends may evolve in the near future (Box 4). For instance, cognitive models are already being extended to account for more detailed aspects of information processing on the level of a single trial [33–35]. As the models become more powerful, the experimental tasks may increase in complexity and ecological validity [36]. In addition, new models may be developed to identify differences in information processing for subsets of participants (e.g., [37]) or subsets of trials (e.g., [38]). Categorization of different participants and trials may greatly increase the specificity with which neuroscientist draw their conclusions.

Box 4. Outstanding questions.

The neuroscientific and behavioral approaches to investigating cognitive theories have only recently begun to be linked in meaningful ways. The benefits – to both fields – of a combined approach are clearest in those cases where formal models have been used as a link. Such studies have advanced knowledge in areas where the exclusive consideration of one type of data or the other does not provide sufficient theoretical constraint: such as in atheoretical localization of cognitive function from neural data without considering behavioral models; or in the differentiation of cognitive accounts that are equivalent in terms of behavioral data. The advances made so far suggest some questions that will become more important as the new field of model-based cognitive neuroscience progresses:

How can we apply our knowledge from formal models and cognitive neuroscience to psychiatric and neurological disorders [48]? Can parameters from cognitive models provide endophenotypes that are more sensitive and specific than those based on observed behavior?

What are the benefits for cognitive neuroscience when relatively abstract cognitive models are combined with more concrete neurocomputational models? As the field of cognitive neuroscience and cognitive modeling grow closer, abstract models should ideally start to incorporate assumptions about the neural substrate.

Can we strengthen our inferences through development of integrated approaches that combine data-driven cognitive neuroscience with cognitive modelling techniques? Initial work with analysis methods such as ancestral graph theory [49] and single trial estimation based on multivariate decomposition (e.g., [50]) point in this direction.

What are the benefits for cognitive neuroscience when mixture models are used to classify participants or trials into separate categories? This approach could for instance be applied to allow the probabilistic identification of task-unrelated thoughts (TUTs), that is, trials on which the participant experiences a lapse of attention.

Cognitive psychologists and cognitive neuroscientists have not always seen eye to eye (e.g., [39–40]). Some cognitive psychologists do not care about brain measurements and believe cognitive neuroscience is mostly an expensive fishing expedition. On the other hand, some cognitive neuroscientist do not care about mathematical models and believe that those who do are on the verge of extinction. Neither bias is helpful or productive. We are enthusiastic about the recent synthesis between formal modeling and cognitive neuroscience, and we believe that by fostering this mutually constraining relationship we will gain insights that have eluded the field since the inception of the cognitive revolution.

Figure 2.

Flowchart for the assessment of model validity.

Figure 3.

The LBA model for response time and accuracy.

Figure 4.

(A) Influence of rewards earned n trials in the past on the log odds of choosing one of two options on the current trial (a clockwise or counter-clockwise rotated grating), where each option was stochastically rewarded at an independent rate. (B) Similar to A, but depicts influence of prior choices on current choice: a prior choice decreases the probability of the same choice being made on the current trial because the task included a ‘baiting’ scheme to encourage switching between alternatives (see refs. 43–47). (C) The estimated influence of prior rewards and choices (panels A,B) can be combined to generate a trial-by-trial estimate of the probability that one of the options will be selected (in this case, the probability of the clockwise grating being selected is shown by the black line after the application of a causal Gaussian filter to smooth the data, see refs. 46–47). The solid green line depicts the expected choice probabilities on each block of trials based on the relative reward probability assigned to each choice alternative. For this subject, the estimated choice probability (black line) closely tracked the expected probabilities, supporting the notion that the estimated choice probability can serve as a stand-in for the subjective value of each alternative. Note, however, that there are local trial-by-trial fluctuations away from the expected choice probabilities, consistent with momentary changes in the subjective value of an option given the stochastic reward structure of the task. Data based on ref. 47.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by VENI and VIDI grants from the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (B.U.F. and E.J.W., respectively); Australian Research Council Discovery Project DP0878858 (S.B.), and National Institutes of Mental Health Grant R01-MH092345 (J.T.S.)

References

- 1.Corrado G, Doya K. Understanding neural coding through the model-based analysis of decision making. J Neurosci. 2007;27:8178–8180. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1590-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dolan RJ. Neuroimaging of cognition: past, present, and future. Neuron. 2008;60:496–502. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Friston KJ. Modalities, modes, and models in functional neuroimaging. Science. 2009;326:399–403. doi: 10.1126/science.1174521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gold JI, Shadlen MN. Neural computations that underlie decisions about sensory stimuli. Trends Cogn Sci. 2001;5:10–16. doi: 10.1016/s1364-6613(00)01567-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mars RB, et al. Model-based analyses: Promises, pitfalls, and example applications to the study of cognitive control. Q J Exp Psychol (Colchester) 2010:1–16. doi: 10.1080/17470211003668272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Doherty JP, et al. Model-based fMRI and its application to reward learning and decision making. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1104:35–53. doi: 10.1196/annals.1390.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Celebrini S, Newsome WT. Neuronal and psychophysical sensitivity to motion signals in extrastriate area MST of the macaque monkey. J Neurosci. 1994;14:4109–4124. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-07-04109.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Geisler WS. Frontiers of Visual Science. National Academy Press; 1987. Ideal-observer analysis of visual discrimination. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ress D, Heeger DJ. Neuronal correlates of perception in early visual cortex. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:414–420. doi: 10.1038/nn1024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ditterich J. A Comparison between Mechanisms of Multi-Alternative Perceptual Decision Making: Ability to Explain Human Behavior, Predictions for Neurophysiology, and Relationship with Decision Theory. Front Neurosci. 2010;4:184. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2010.00184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grafton ST, et al. Neural substrates of visuomotor learning based on improved feedback control and prediction. Neuroimage. 2008;39:1383–1395. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.09.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown SD, Heathcote A. The simplest complete model of choice response time: linear ballistic accumulation. Cogn Psychol. 2008;57:153–178. doi: 10.1016/j.cogpsych.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Forstmann BU, et al. The neural substrate of prior information in perceptual decision making: a model-based analysis. Front Hum Neurosci. 2010;4:40. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2010.00040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lauwereyns J. The anatomy of bias: How neural circuits weigh the options. MIT Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gold JI, Shadlen MN. The neural basis of decision making. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2007;30:535–574. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.29.051605.113038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sevy S, et al. Emotion-based decision-making in healthy subjects: short-term effects of reducing dopamine levels. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;188:228–235. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0450-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yechiam E, et al. Using cognitive models to map relations between neuropsychological disorders and human decision-making deficits. Psychol Sci. 2005;16:973–978. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2005.01646.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Forstmann BU, et al. Striatum and pre-SMA facilitate decision-making under time pressure. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:17538–17542. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805903105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Forstmann BU, et al. Cortico-striatal connections predict control over speed and accuracy in perceptual decision making. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:15916–15920. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004932107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Behrens TE, et al. Learning the value of information in an uncertain world. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1214–1221. doi: 10.1038/nn1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Noppeney U, et al. Perceptual decisions formed by accumulation of audiovisual evidence in prefrontal cortex. J Neurosci. 2010;30:7434–7446. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0455-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu AJ, et al. Dynamics of attentional selection under conflict: toward a rational Bayesian account. J Exp Psychol Hum Percept Perform. 2009;35:700–717. doi: 10.1037/a0013553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Borst JP, et al. The neural correlates of problem states: testing FMRI predictions of a computational model of multitasking. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12966. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anderson JR, et al. A central circuit of the mind. Trends Cogn Sci. 2008;12:136–143. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Anderson JR, Qin Y. Using brain imaging to extract the structure of complex events at the rational time band. J Cogn Neurosci. 2008;20:1624–1636. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2008.20108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anderson JR, et al. Using fMRI to test models of complex cognition. Cognitive Science. 2008;32:1323–1348. doi: 10.1080/03640210802451588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ratcliff R, et al. Quality of evidence for perceptual decision making is indexed by trial-to-trial variability of the EEG. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:6539–6544. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812589106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ashby FG, et al. Cortical and basal ganglia contributions to habit learning and automaticity. Trends Cogn Sci. 2010;14:208–215. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2010.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stocco A, et al. Conditional routing of information to the cortex: a model of the basal ganglia’s role in cognitive coordination. Psychol Rev. 2010;117:541–574. doi: 10.1037/a0019077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Churchland AK, et al. Decision-making with multiple alternatives. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:693–702. doi: 10.1038/nn.2123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Usher M, et al. Hick’s law in a stochastic race model with speed-accuracy tradeoff. Journal of Mathematical Psychology. 2002;46:704–715. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Purcell BA, et al. Neurally constrained modeling of perceptual decision making. Psychol Rev. 2010;117:1113–1143. doi: 10.1037/a0020311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Lange FP, et al. Accumulation of evidence during sequential decision making: the importance of top-down factors. J Neurosci. 2010;30:731–738. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4080-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krajbich I, et al. Visual fixations and the computation and comparison of value in simple choice. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:1292–1298. doi: 10.1038/nn.2635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Resulaj A, et al. Changes of mind in decision-making. Nature. 2009;461:263–266. doi: 10.1038/nature08275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Behrens TE, et al. Associative learning of social value. Nature. 2008;456:245–249. doi: 10.1038/nature07538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wetzels R, et al. Bayesian inference using WBDev: a tutorial for social scientists. Behav Res Methods. 2010;42:884–897. doi: 10.3758/BRM.42.3.884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vanderkerckhove J, et al. Hierarchical diffusion models for two-choice response times. Psychological Methods. doi: 10.1037/a0021765. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Coltheart M. What has functional neuroimaging told us about the mind (so far)? Cortex. 2006;42:323–331. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(08)70358-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Page MP. What can’t functional neuroimaging tell the cognitive psychologist? Cortex. 2006;42:428–443. doi: 10.1016/s0010-9452(08)70375-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ratcliff R, McKoon G. The diffusion decision model: theory and data for two-choice decision tasks. Neural Comput. 2008;20:873–922. doi: 10.1162/neco.2008.12-06-420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van Ravenzwaaij D, et al. Cognitive model decomposition of the BART: Assessment and application. Journal of Mathematical Psychology. 55:94–105. (in press) [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sugrue LP, et al. Matching behavior and the representation of value in the parietal cortex. Science. 2004;304:1782–1787. doi: 10.1126/science.1094765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Corrado GS, et al. Linear-Nonlinear-Poisson models of primate choice dynamics. J Exp Anal Behav. 2005;84:581–617. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2005.23-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Serences JT. Value-based modulations in human visual cortex. Neuron. 2008;60:1169–1181. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lau B, Glimcher PW. Dynamic response-by-response models of matching behavior in rhesus monkeys. J Exp Anal Behav. 2005;84:555–579. doi: 10.1901/jeab.2005.110-04. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Serences JT, Saproo S. Population response profiles in early visual cortex are biased in favor of more valuable stimuli. J Neurophysiol. 2010;104:76–87. doi: 10.1152/jn.01090.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maia TV, Frank MJ. From reinforcement learning models to psychiatric and neurological disorders. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:154–162. doi: 10.1038/nn.2723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Waldorp L, et al. Effective connectivity of fMRI data using ancestral graph theory: dealing with missing regions. Neuroimage. 2011;54:2695–2705. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2010.10.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eichele T, et al. Prediction of human errors by maladaptive changes in event-related brain networks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:6173–6178. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708965105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]