Abstract

Methamphetamine (METH), a potent stimulant with strong euphoric properties, has a high abuse liability and long-lasting neurotoxic effects. Recent studies in animal models have indicated that METH can induce impairment of the blood brain barrier (BBB), thus suggesting that some of the neurotoxic effects resulting from METH abuse could be the outcome of barrier disruption. Here we provide evidence that METH alters BBB function via direct effects on endothelial cells and explore possible underlying mechanisms leading to endothelial injury. We report that METH increases BBB permeability in vivo, and exposure of primary human microvascular endothelial cells (BMVEC) to METH diminishes tightness of BMVEC monolayers in a dose- and time-dependent manner by decreasing expression of cell membrane associated tight junction (TJ) proteins. These changes were accompanied by enhanced production of reactive oxygen species, increased monocyte migration across METH-treated endothelial monolayers, and activation of myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) in BMVEC. Anti-oxidant treatment attenuated or completely reversed all tested aspects of METH induced BBB dysfunction. Our data suggest that BBB injury is caused by METH-mediated oxidative stress, which activates MLCK and negatively affects the TJ complex. These observations provide a basis for antioxidant protection against brain endothelial injury caused by METH exposure.

Keywords: methamphetamine, blood brain barrier, oxidative stress, tight junction, monocyte

Introduction

Methamphetamine (METH) is a synthetic drug that is easily abused due to its powerful psychostimulant and addictive properties. Abuse of METH is a growing problem in the US; epidemiological studies indicate that ~4.9% of Americans have tried METH at least once in their life (Tata and Yamamoto 2007). In 2004, statistics from the Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN) showed that METH related emergency department admissions accounted for 8% of all admissions or over 150,000 cases that year, underscoring that short and long-term abuse of METH leads to deleterious health effects. In the brain, METH toxicity has been characterized by disruption in monoamine production and synaptic integrity of the dopaminergic system. Furthermore, METH neurotoxicity also generates a strong and lasting glial response, resulting in astrogliosis and release of inflammatory mediators. Recently, the brain endothelium has also been shown to be a target of METH toxicity. METH exposure in vivo has been shown to disrupt the function of the blood brain barrier (BBB) (Sharma and Kiyatkin 2009).

METH-induced pathophysiological changes (hyperthemia, hyponatremia, and hypertension) can result in increased BBB permeability (Persidsky et al 2006b). Quinton and Yamamoto (Quinton and Yamamoto 2006) showed that administration of the METH derivative, 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA; ecstasy), produced long lasting disruptions of BBB permeability in the striatum and the dorsal hippocampus. Similarly, Bowyer and colleagues (Bowyer et al 2008) demonstrated BBB-increased permeability in the limbic region (the medial and ventral amygdala and the hippocampus). The underlying mechanism of METH-induced BBB impairment remains poorly understood.

HIV-1 seroincidence associated with METH use is 5.8 times higher than among non-abusers (Mansergh et al 2006). Clinical studies indicate that METH dependence has an additive effect on cognitive deficits associated with HIV-1 infection (Chana et al 2006). The causes of HIV-1-associated neurotoxicity include excitotoxic effects of glutamate, secretory products of chronically activated glial cells, and oxidative stress (Ellis et al 2007) very similar culprits to those mediating METH-induced neuronal injury (O’Dell and Marshall 2005; Quinton and Yamamoto 2006; Sekine et al 2008; Stephans and Yamamoto 1994). BBB dysfunction is a common feature of HIV-1 neurodegeneration (Persidsky et al 2006b). Taken together, METH abuse and HIV-1 central nervous system (CNS) infection could lead to combined injury, resulting in enhanced neural compromise and cognitive dysfunction.

Multiple studies indicate that METH-induced neurotoxicity involves the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and nitrogen species (Flora et al 2003). The role of oxidative stress is further supported by the finding that the ROS scavengers and antioxidants attenuate the neurotoxic effects of METH (Fukami et al 2004). Considering that oxidative stress plays a significant role in METH-mediated neurotoxicity, we hypothesized that ROS generation mediated by METH also occurs in brain endothelium, resulting in BBB compromise via activation of myosin light chain kinase (MLCK) which increases BBB permeability via modifications of tight junctions (TJ) and cytoskeleton (Haorah et al 2005). Also, we posed the question whether alterations in the barrier by METH promotes monocyte transendothelial migration, to support the notion that METH BBB disruption is a contributing factor in HIV-1 neuropathogenesis. Using primary human brain microvascular endothelial cells (BMVEC), we demonstrated that METH exposure led to ROS generation, decreased expression of TJ proteins, increased BBB permeability and enhanced monocyte migration across BMVEC monolayers. Antioxidant administration prevented METH-induced effects in brain endothelium suggesting both an underlying mechanism and a potential treatment approach for drug-induced BBB dysfunction.

Materials and Methods

Animals and drug administration

Four-week old male NOD/C.B-17 SCID mice purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) were maintained in sterile microisolator cages under pathogen-free conditions in accordance with institutional ethical guidelines for care of laboratory animals, National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines, and the Institutional Animal Care Use Committee. Animals were weight-matched and randomly assigned to various treatment groups. A common pattern in most recreational METH abusers is initial use of lower doses progressively increasing to higher doses and eventually engaging in multiple daily administrations. Therefore to simulate this pattern of METH exposure, we adapted a safe escalating dosing regimen (Schmidt et al 1985) that does not produce potentially lethal hyperthermia in METH treated animals, while simultaneously producing similar stimulant effects seen in human METH abusers that binge. Mice received seven subcutaneous (s.c.) injections of 1.5–10.0 mg/kg METH or sterile 0.9% sodium chloride. Injections were administered in incremental doses on alternating days. On day 9, once the animals reached a total dose of 10mg/kg, 4 doses of 10 mg/kg every 2 hr were injected. A single dose of Trolox (50 mg/kg) was administered i.p on alternate days (Diaz et al 2007).

Cell culture

Human brain microvascular endothelial cells (BMVEC) were cultured from the resection path tissue recovered from the removal of epileptogenic cerebral cortex material in procedures of surgical treatment of epilepsy. The isolation of brain microvessels and the subsequent expansion of the endothelial culture were performed and provided by Michael Bernas and Dr. Marlys Witte (University of Arizona Health Science Center, Tucson, AZ). Transfer and use of the BMVEC cultures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at Temple University. BMVEC were maintained in DMEM/F-12 media containing 10% fetal bovine serum, endothelial cell growth supplement (ECGS, BD, Franklin Lakes, NJ), heparin (1mg/ml, Sigma, St. Louis, MO), amphotericin B (2.5μg/ml, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), penicillin (100U/ml, Invitrogen) and streptomycin (100μg/ml, Invitrogen). BMVEC of low passages and from different donors were used in repeated experiments. Confluent monolayers of BMVEC were changed to media containing the above formulation but lacking the ECGS and heparin. To confirm the presence of barrier formation, transendothelial electrical resistance was measured and the presence of typical brain endothelial markers was verified. For certain studies (as indicated in the figures), a telomerase immortalized human brain endothelial cell line was used. This hCMEC/D3 cell line exhibits similar properties to those seen in primary BMVEC and are routinely used in in vitro modeling of the BBB (Weksler et al 2005) Experiments were performed in both primary cells and on the cell line hcMEC/D3; all results shown are from primary endothelial cells except for those in Figure 2, which shows results from hCMEC/D3. Preliminary experiments demonstrated that METH at concentrations 5 μM – 1 mM did not affect viability of brain endothelial cells after 48 hr of exposure (data not shown).

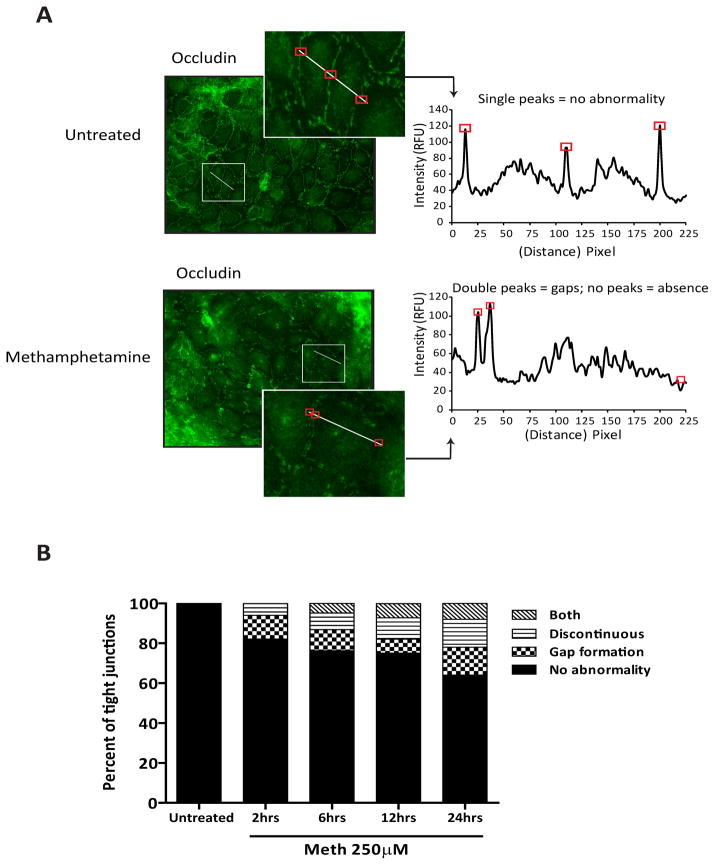

Figure 2.

Altered TJ appearance in METH-treated BMVEC. HCMEC/D3 cells were used for the results shown here. (A) Representative images showing immunofluorescence labeling of occludin depict a continuous pattern for the TJ in untreated monolayers. Discontinuous occluding staining and gap formation are found in monolayers treated with 250 μM METH for 24 hr. The histogram inserts depict values as intensity/pixel from intensity profile lines drawn across the interface (TJ) of adjacent cells. The intensity histograms graphically demonstrate where gaps (double peaks) or discontinuity at the TJ occurs (absent or small peaks). Boxes around areas in images correspond to peaks on densitometry graphs. (B) Based on the intensity line profile, the degree of occludin alteration at the cell junction was evaluated by a semi-quantitative image analysis of multiple cell junctions using the criteria described above. Because the endothelial cells have various contact points with adjacent cells, only one contact point per cell was used in the analysis. The image analysis comparing untreated endothelial cells and METH-treated cells at various times is also shown. The data is presented as the percent of cells displaying 1 of 4 categories: no abnormality, gap formation, discontinuous or discontinuous with gaps (both).

Primary human monocytes isolated by countercurrent centrifugal elutriation were obtained from the Human Immunology Core at the University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia, PA). The cells were maintained in DMEM containing heat inactivated 10% fetal bovine serum, penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 U/ml), and L-glutamine (2mM) and were used within 24 hr of elutriation.

Evaluation of BBB permeability

Changes in BBB permeability were assessed using the fluorescent tracer, sodium-fluorescein (Na-F); the procedure performed was a modification of previously described methods (Lenzser et al 2005; Phares et al 2007). Briefly, animals were injected i.p with 100μl of 2% Na-F in PBS. The tracer was allowed to circulate for 30 min. The mice were then transcardially perfused with PBS until colorless perfusion was visualized. The animals were then decapitated and the brains quickly isolated. After removal of the meninges, cerebellum, and brain stem, the tissue was weighed and homogenized in 10 times volume of 50% trichloroacetic acid. The homogenate was centrifuged for 10 min at 13000xg and the supernatant was neutralized with 5 M NaOH (1:0.8). Measurement of Na-F fluorescence was determined at excitation/emission wavelengths of 440/525 nm using a SpectraMax M5 microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Fluorescent dye content was calculated using external standards with a range of 10–200ng/ml, and the data are expressed as amount of tracer per gram of tissue.

Measurement of Transendothelial Electrical Resistance (TEER)

To determine the integrity of brain endothelial monolayers, TEER measurements were performed using the 1600R ECIS system (Applied Biophysics, Troy, NY). The ECIS system provides real-time monitoring of changes in TEER. In brief, BMVEC at 1×105/well were plated on collagen type I coated 8W10E electrode arrays (Applied Biophysics). The cells were then allowed to form monolayers reaching stable TEER values. After seven days (with media change every three days), the monolayers were exposed to various concentrations of METH as indicated. The readings were acquired continuously for 12 hr at 400 hz and at 10 min intervals. Confluent BMVEC monolayers demonstrated baseline TEER readings between 1500–2400 Ω/cm2. The data is shown as percent change of baseline TEER along with the SEM of condition replicates.

Immunofluorescence staining

Assessment of TJ protein distribution and expression was performed by indirect immunofluorescence. Using standard immunohistochemistry methods, monolayers of hCMEC/D3 on type I collagen coated coverslips (BD) were fixed with 3% (v/v) formaldehyde (Polysciences Inc, Warrington, PA) and permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS. Primary antibodies and dilutions used included: polyclonal antibodies to occludin (1:100, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and monoclonal antibodies to ZO-1 (1:100, Invitrogen). The cells and primary antibodies were incubated overnight at 4°C. For occludin staining, the cells were pre-extracted for 2 min on ice with ice cold 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS prior to fixation. The secondary antibodies used included: Alexa-fluor 488-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit antibodies (1:400, Invitrogen) and Alexa-fluor® 594-conjugated donkey anti-mouse antibodies. After removal and rinsing of the primary antibodies, the secondary antibodies were incubated with the cells at room temperature for 1 hr. Cells were then washed and mounted onto slides with ProLong Antifade plus DAPI® (Invitrogen). Immunofluorescence was visualized with a Nikon Eclipse 80i fluorescent microscope (Nikon, Japan).

Image analysis of TJ protein alteration

TJ abnormalities were evaluated by dual labeling of ZO-1 and occludin followed by measurement of pixel intensity across the TJ. Images were captured at 20X magnification from monolayers with or without METH exposure with camera setting kept uniform (i.e., exposure time) throughout all experimental sets. Line histograms, to identify values of intensity/pixel, were placed perpendicular to the TJ and intensity measured.

Because endothelial cells have various contact points with adjacent cells, only one contact point per cell selected at random was used in the analysis. The TJ intensity profiles from each condition were grouped into the following categories: intensity profiles that exemplified sharp TJ or no abnormality (a single peak), gaps (multiple peaks), discontinuity (low or absent peaks), or both gaps and discontinuity. Visualization of immunofluorescence was performed using an Eclipse 80i microscope (Nikon), fitted with a CoolSnap-EZ digital camera (Photometrics, Tucson, AZ). Image acquisition/analysis was performed with NIS Elements R (Nikon) imaging software. The data represent the analysis from at least 5 images from each replicate condition (w/o METH) and from three independent experiments.

Protein preparation and immunoblotting

Confluent monolayers of BMVEC were prepared for whole cell lysate or for membrane and cytosolic fractions. Cells were lysed with CelLytic-M (Sigma) for preparation of whole cell lysates. Cellular fractions were collected using the ProteoExtract kit (Calbiochem) as outlined by the manufacturer’s protocol and described by Stamatovic et al. (Stamatovic et al 2006). The protein concentrations in whole lysates or fractions were estimated using the BCA method (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). Cellular fractions or whole cell lysates were loaded at 50 μg/lane and resolved by SDS-PAGE on 4–20% precast gradient gels (Thermo Scientific). Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes and incubated overnight with polyclonal antibodies against occludin (1:500, Invitrogen), claudin-5 (1:500, Invitrogen), myosin light chain, MLC 2 (1:100, Cell Signaling Technologies, Danvers, MA) and phospho-MLC 2 (S19, 1:100, Cell Signaling Technologies), and β-tubulin (1:1000, Abcam, Cambridge, MA). Secondary antibodies conjugated to HRP were then added for 1 hr and then detected using Supersignal West Pico chemiluminescence substrate (Thermo Scientific). Chemiluminescence signal detection was performed with the gel documentation system G:Box Chemi HR16 (Syngene, Frederick, MD). Densitometry analysis was performed with GeneTools software package (Syngene).

ROS measurement

Detection of ROS generation was measured in BMVEC monolayers with the fluorescence probe, 5-(and-6)-chloromethyl-2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (CM-H2DCFDA, Invitrogen). After 24 hr treatment of the experimental conditions (as shown in Figure 4), the cells were washed three times with serum-free media and then loaded with 10μM CM-H2DCFDA in serum-free media for 45 min at 37°C. Once inside the cell, the cell permeable H2DCFDA becomes fluorescent following the removal of the acetate groups and oxidation of the indicator has occurred. After the loading of the indicator, the cells were washed once with HBSS and the fluorescence measured at excitation/emission wavelengths of 495/525 nm using kinetic mode settings of 5 min intervals on a SpectraMax M5 microplate reader (Molecular Devices). When present, the concentration of the antioxidant Trolox was 25 μM, consistent with previous reports by other investigators (Martin et al 2005; Yatin et al 2002). The data for the 30 min time point are shown in the figure and expressed as relative fluorescence.

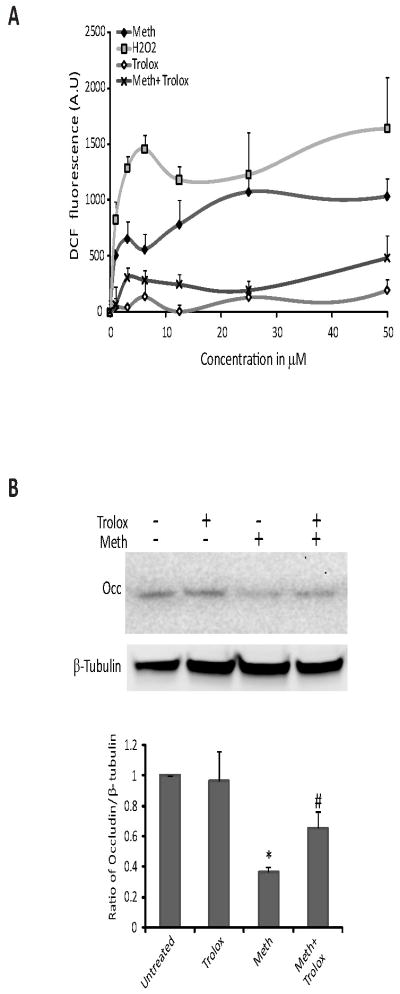

Figure 4.

METH generates ROS in the BMVEC. (A) BMVEC were exposed to increasing concentrations of either H2O2 (control), METH or the antioxidant Trolox (6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid). In parallel, cells were exposed together with increasing concentration of METH and a fixed concentration of Trolox (25 μM). The results show the fluorescence readings acquired 30 min after the start of treatments. METH generated a dose-dependent increase in the amount of ROS; however in the presence of Trolox, ROS production was significantly inhibited (p<0.005 when compared to METH-exposed cells). Data represent the mean values ± SEM (n=3). (B) Western blot shows occludin levels after 24 hr in untreated BMVEC, Trolox-treated (25 μM), METH-treated (50 μM) and METH with Trolox treated BMVEC. Densitometry values were used to quantify decreases in occludin due to METH treatment (bar graph).

Migration assay

In order to quantitatively measure the transendothelial migration of monocytes in vitro, a fluorescence-based assay was used as previously described (Ramirez et al 2008). In brief, BMVEC at 2.5 ×104 cells/insert were plated on type I collagen coated FluoroBlok® tissue culture inserts (with 3 micron pores, BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ). Since the cells on these inserts cannot be visualized by microscopy, TEER measurements taken with a voltmeter (EVOM, World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL) confirmed that the monolayers displayed typical barrier formation (Persidsky et al 2006a). The endothelial cells were then treated (as indicated in Figure 5) for 24 hr. Prior to initiation of the migration assay, all treatments were removed and media replaced lacking the experimental compounds. Monocytes were labeled with the cell tracker, calcein-am (Invitrogen), according to manufacturer’s instructions and then introduced to the endothelial monolayers at 1×105 cells/insert. Monocytes were migrated in the absence or the presence of recombinant human monocyte chemotactive protein (MCP)-1 (CCL2/MCP-1, 30ng/ml, R&D Systems) placed into the lower chamber of the insert system. The cells were incubated under normal tissue culture conditions and the migration of fluorescently labeled monocytes was measured at 2 hr. Measurement of relative fluorescence was acquired from the lower chamber using M5 fluorescence plate reader. Calculations for the actual number of migrated monocytes were derived from external standards of labeled monocytes. The data are shown as the fold difference of migrated cells compared to the background migration of cells in inserts without chemoattractant or experimental treatments.

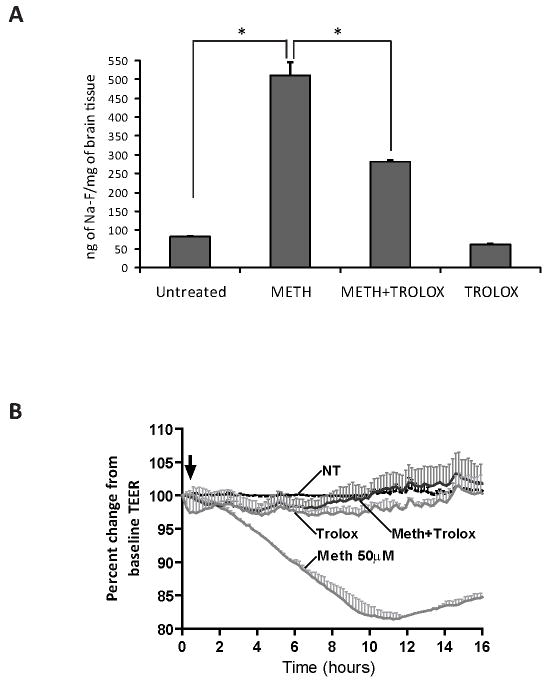

Figure 5.

Antioxidant treatment prevented METH-induced barrier dysfunction in vivo and in vitro. Four-week old male NOD SCID mice received seven s.c. injections of either METH, sterile 0.9% sodium chloride, Trolox (50 mg/kg administered i.p every other day) or in combination with METH and Trolox. Na-F administration was used to evaluate BBB permeability. Animals were then perfused to eliminate tracer in the vessels. The data shown in (A) indicate the accumulation of the tracer as ng of Na-F per mg of brain tissue (average ± SEM, n=5). (B) TEER readings are shown in monolayers that were untreated or treated with METH (50 μM), Trolox only (25 μM), or both METH and Trolox. Untreated and Trolox only treated monolayers sustained basal levels of TEER. METH addition produced a drop in TEER, whereas in the presence of Trolox, the effects of METH on TEER were prevented. The resistance was measured at 400 Hz at 10 min intervals for the duration of the experiments. Treatments were initiated (arrow) after stable resistance was reached. The data represent the percent of the mean value ± SEM (n=3).

Data analysis

The results were gathered from at least three independent experiments. Within an individual experiment, each data point was determined from three to five replicates. Apart from the densitometry analysis which is expressed as the mean ± SD, all other values are expressed as the mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis of the data was performed using Graphpad Prism v5 (Sorrento Valley, CA). Comparisons between samples were performed by unpaired Student’s t-test; multiple group comparisons were performed by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post-hoc tests. Differences were considered significant at P values ≤0.05.

Results

Increase in BBB permeability and BBB integrity disruption by METH

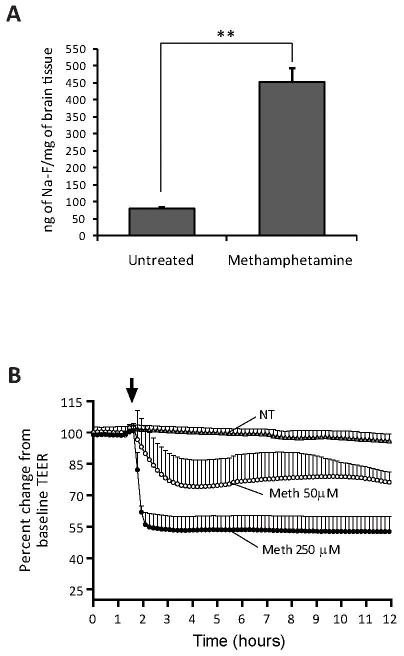

While neuronal injury and glial activation has been well documented in METH-associated CNS injury, few studies have focused on the effect of METH on the cerebral microvasculature (Sekine et al 2008). Recent reports have suggested that an increase in BBB permeability occurs in animals exposed to high doses of METH. Bowyer et al. (Bowyer et al 2008) found accumulation of IgG around microvessels indicating significant BBB disruption. In order to evaluate barrier dysfunction in a quantitative manner, we treated mice with escalating doses of METH (1.5–10.0 mg/kg METH on days 1–7) or with sterile 0.9% sodium chloride. Thirty min prior to sacrifice, the animals were injected with the small molecular tracer sodium fluorescein (Na-F, 376 Da) and the Na-F tissue content was measured. METH exposure led to a seven-fold increase of BBB permeability as compared to vehicle controls (Fig. 1A). Next, we evaluated whether METH directly affects BBB integrity. Primary human BMVEC were grown on ECIS array electrodes and TEER was monitored continuously over the course of 12 hr. Formation of confluent monolayers achieved typical basal-level TEER readings of at least 1,500Ω/cm2. After METH application, average TEER measurements showed a 20–50% drop in resistance in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1B). The lower concentration of METH (50 μM) induced a gradual decrease in TEER that rebounded slightly, whereas the higher METH dose (250 μM) produced a quicker and sustained drop in TEER values, indicating a partial loss of monolayer integrity. Therefore, both in vitro and in vivo data point to a rapid BBB compromise after drug exposure.

Figure 1.

METH induction of BBB leakiness in vivo and in vitro. (A) Four-week old male NOD SCID mice received seven s.c. injections of either METH or sterile 0.9% sodium chloride. BBB permeability was evaluated by administration of the tracer, sodium fluorescein (Na-F) in saline, via i.p. route as described in the Methods. Following perfusion, the content of Na-F in homogenized brain tissue was measured. The results are expressed in ng of Na-F/mg of brain tissue, showing the average ± SEM, n=5, **p<0.001. (B) Barrier function is compromised in METH-treated BMVEC. TEER, an indicator of barrier integrity, was measured (by ECIS) in monolayers untreated or treated with either 50 μM or 250 μM METH. The resistance was measured at 400 Hz in 10 min intervals for the duration of the time shown. Treatments were initiated (arrow) after stable resistance was reached. Each data point is represented as the percent of the mean value ± SEM (n=3).

Appearance of TJ abnormalities in METH-treated endothelial cells

Barrier tightness and high electrical resistance are mediated by the level and distribution of the TJ proteins connecting brain endothelial cells (Persidsky et al 2006b). Consequently, the diminished barrier function correlates with down-regulation of TJ proteins or their redistribution from the membrane to the cytosol (Aghajanian et al 2008). To evaluate whether the effect of METH on BBB permeability may be explained by morphological differences in TJ formation, we examined the expression and distribution of occludin, ZO-1 and claudin-5. Indeed, microscopy analysis of immunofluorescence labeled occludin showed that BMVEC exposed to METH had increased numbers of altered TJ displaying low occludin staining and gap formation (Fig. 2A). These changes are in stark contrast to the untreated control cells, where occludin staining showed sharp and continuous TJ. To evaluate the TJ abnormalities, semi-quantitative image analyses were performed using pixel intensity measurements across cellular junctions throughout METH treated and untreated monolayers (Fig. 2B). The results showed progressive TJ alterations over the period of METH exposure (Fig. 2B). Staining for claudin-5 demonstrated similar results (data not shown). However, no noticeable distribution or expression changes were evident in the TJ anchoring protein, ZO-1 (data not shown), suggesting the involvement of differential effects of METH on different TJ proteins.

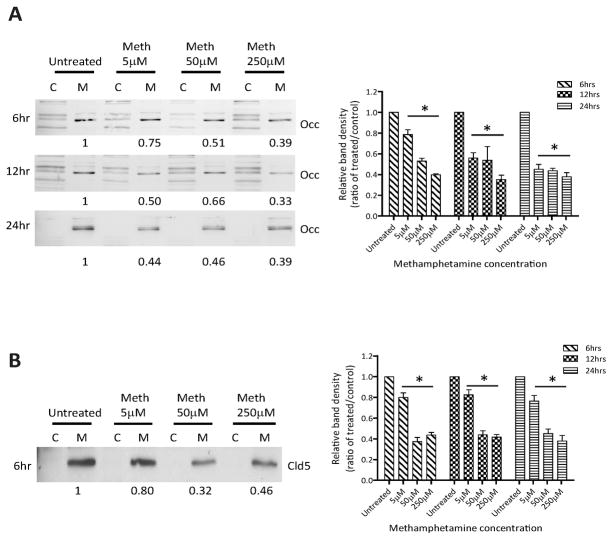

METH downregulates the expression of TJ proteins

TJ changes after METH treatment were further evaluated by Western blot. We analyzed levels of occludin and claudin-5 in membranous and cytoplasmic fractions of BMVEC. Figure 3A indicates a dose- and time-dependent decrease in occludin content at the membrane by 25–67%. While at the 6 hr time point, higher doses (50 and 250 μM) caused more prominent reduction of occludin as compared to 5 μM. Longer exposure with low dose METH also resulted in further loss of TJ protein at the membrane. Similar results were also found for claudin-5 levels after METH application (Fig. 3B). Western blot analyses demonstrated a decrease in claudin-5 expression (20–68%) in membranous fractions of BMVEC exposed to different concentrations of METH as compared to untreated control. In contrast to occludin, claudin-5 did not appear to follow a time dependent decrease in expression within a given METH concentration. Thus suggesting that claudin-5 is more stable than occludin after METH insult. Interestingly, no redistribution or increased cytosolic content of occludin and claudin-5 was observed, suggesting that is not redistribution but an inhibition in protein expression that results from METH exposure.

Figure 3.

METH downregulates levels of TJ proteins in BMVEC. Shown are representative western blots of occludin (Occ) (A) and claudin-5 (Cld5) (B) from membranous (M) and cytosolic (C) cellular fractions of endothelial cells treated at various time points (6, 12, and 24 hr) and at different concentrations (5, 50 and 250 μM) of METH. The graphs represent densitomet analysis of the band intensity ratio of METH over the untreated control. The results are shown as the mean value ± SD (*p<0.05 versus control), from three independent experiments.

ROS generation in METH-exposed BMVEC

Considering that oxidative stress plays an important role in neurotoxic effects of METH, we sought to determine whether METH could enhance ROS production in BMVEC at non-toxic concentrations. Using the ROS-sensitive dye, DCF, BMVEC were exposed to increasing concentrations of either H2O2 (control), METH or the antioxidant, Trolox (6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchroman-2-carboxylic acid). In parallel, cells were exposed to both increasing concentrations of METH and Trolox (25 μM). The results show the readings acquired at 30 min after the start of treatments. METH generated a dose-responsive increase in the amount of ROS production, shown by the increase in fluorescence from the DCF indicator. However, METH in the presence of Trolox showed significant inhibition of ROS production (p<0.005 when compared to METH-exposed cells, Fig. 4A). We next assessed the potential protective effects of the antioxidant, Trolox, on TJ protein expression. As seen earlier, exposure of 50 μM METH for 24 hr downregulated occludin. Addition of Trolox together with METH partially restored occludin levels (Fig. 4B). Similar to occludin, claudin-5 levels were preserved by Trolox (data not shown). Taken together, these results suggest a potential contribution of oxidative stress to brain endothelial alterations elicited by METH.

Trolox restores BBB integrity in vivo and in vitro

Next, we studied whether leakiness in the BBB could be prevented in animals exposed to escalating doses of METH. Mice received escalating injections of either METH or sterile 0.9% sodium chloride (reaching a final concentration of 10 mg/kg) over a period of seven days. Trolox groups received a single dose of antioxidant (50 mg/kg, i.p.) every other day from the start of METH administration. On day 9, when the animals reached a total dose of 10mg/kg, the animals were administered the permeability tracer, Na-F. BBB permeability was measured by detection of Na-F in the brain tissue. As before, METH increased BBB permeability approximately seven fold. In contrast to METH only administered animals, mice treated with METH and the antioxidant (Trolox) showed significant reduction in the amount of the fluorescence tracer in the brain tissue (two-fold, p<0.005) when compared to METH-treated animals (Fig. 5A). Of note, mice treated with only Trolox (used as controls) showed no change in BBB permeability. In parallel, we measured BMVEC monolayer integrity by TEER. METH application led to a significant drop in TEER (Fig. 5B). Addition of antioxidant together with METH rendered complete protection and thereby maintained TEER at control levels (Fig. 5B). Therefore, multiple lines of evidence indicate that antioxidants could ameliorate barrier demise after METH exposure.

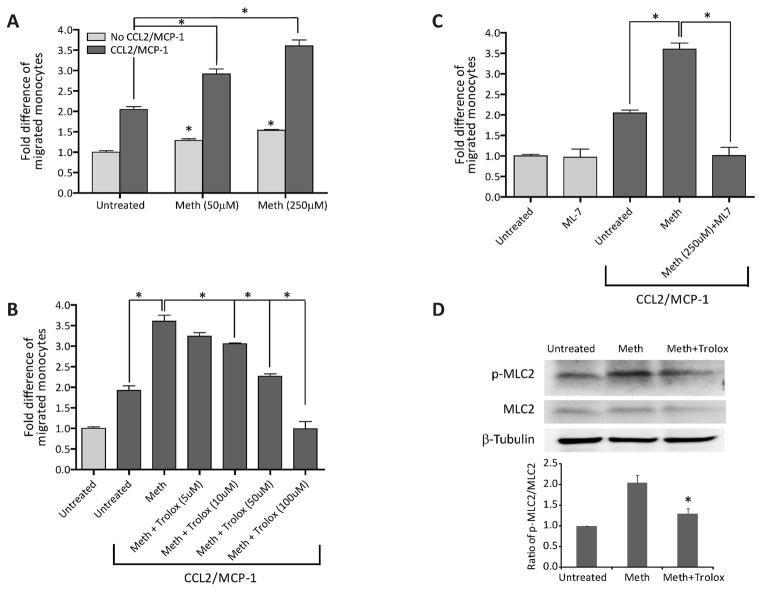

METH augments monocyte transendothelial migration

HIV-1 infection of the CNS is associated with enhanced migration of monocytes across the BBB. Such cell trafficking is mediated by enhanced production of the β-chemokine, CCL2 (MCP-1) in the brain (Persidsky et al 1999). Given the high prevalence of HIV-1 infection in METH abusers, we explored the possibility that METH injury of the BBB could increase monocyte transendothelial migration. We investigated monocyte migration after BMVEC treatment with METH (18 hr) using a model previously established from our laboratory (Ramirez et al 2008). Drug treatment resulted in 25–50% augmentation of monocyte passage through the BBB model. There was a two-fold increase in monocyte migration in response to CCL2. The combination of METH and β-chemokine resulted in a significant enhancement in monocyte migration, which was dose-dependent and synergistic (Fig. 6A, 100% and 150% by 50 or 250μM METH treatments, respectively, as compared to CCL2 alone, p < 0.05). Next, we tested the ability of antioxidant to prevent METH-induced monocyte migration. Indeed when added together with METH, Trolox attenuated monocyte migration in a dose-dependent fashion, and at high concentration, the antioxidant was able to decrease monocyte migration induced by CCL2 and METH to control levels (Fig. 6B). Our previous work related to BBB dysfunction associated with oxidative stress pointed to possible downstream activation of MLCK by ROS. Pre-treatment of BMVEC monolayers with MLCK inhibitor (ML-7) prevented the effects of METH/CCL2 on monocyte migration (Fig. 6C). To further confirm the involvement of the MLCK pathway in METH-treated cells, we looked into the status of MLC phosphorylation, which is a downstream effector of MLCK. In fact, METH application did enhance the levels of p-MLC with a significant return to control levels by the addition of Trolox introduced together with METH (Fig. 6D). Taken together, these data strongly support the role of oxidative stress in BBB impairment with MLCK possibly mediating the effects of ROS in endothelium.

Figure 6.

METH-increased monocyte transendothelial migration via activation of MLCK in endothelial cells. Monolayers of primary BMVEC were left untreated or were exposed to METH at the concentrations shown for 12 hr (A). After treatment removal, monocytes loaded with the cell tracker Calcein-AM, were added to the endothelial monolayers and the relative fluorescence was measured. (B) Co-exposure with the antioxidant Trolox and 250 μM METH, decreased migration in a dose-dependent manner. (C) MLCK inhibitor, ML-7, blocked METH/CCL2-induced monocyte migration across BMVEC monolayers. For panels A–C, the data are represented as the mean ± SEM (n=3) of fold difference. All conditions were compared against the “spontaneous” migration value of untreated cells without chemoattractant. Brackets indicate t-test comparisons for the indicated experimental conditions (*p<0.05). (D) Western blot demonstrates MLC phosphorylation caused by 250 μM METH exposed for 24 hr. Introduction of Trolox at the same time METH was added prevents MLC addition.

Discussion

Chronic and long-term METH abuse damages multiple organ systems; however, none is more prominent than in the brain. METH neurotoxicity disrupts normal neuronal communication in the dopaminergic system and induces neuroinflammation due to glial activation (Sekine et al 2008). METH neurotoxicity manifests as severe cognitive deficits, such as memory loss and psychotic behavior. Because METH use also occurs by intravenous injection and behavior changes include a propensity to engage in precarious sexual behavior, METH users are more at risk of contracting HIV-1 (HIV & drugs. Meth use develops stronger link to HIV risk 2005). One of the consequences of HIV-1 infection is the development of HIV-1 encephalitis (HIVE) characterized by monocyte migration across BBB. Increased HIV-1 infection among METH users creates an additional layer of complexity in understanding the harmful effects that METH has on the brain. In recent years, METH is increasingly being recognized as a damaging agent not only to the neuronal environment, but also to the cerebral vasculature.

Although much is known about the devastating effects of METH on neuronal and glial function, the effect of METH on the brain endothelium remains largely under-characterized. Interestingly the BBB compromise present in HIVE (Avison et al 2004) was recently demonstrated in vivo after METH administration (Quinton and Yamamoto 2006); however, the underlying mechanisms were not addressed. The main goal of this study was to provide evidence that METH can alter BBB function via direct effects on endothelial cells and to explore possible underlying mechanisms leading to endothelial injury. Our experiments demonstrated enhanced BBB permeability, diminished tightness of BMVEC monolayers, decreased expression of cell membrane associated TJ proteins, ROS production, and increased monocyte migration across METH-treated endothelial monolayers. These functional alterations were accompanied by activation of MLCK. Importantly, anti-oxidant treatment attenuated or completely reversed all tested aspects of METH induced BBB dysfunction.

METH-induced hyperthermia and hypertension may lead to increased BBB permeability (Persidsky et al 2006b). Indeed, two groups (Bowyer and Ali 2006; Quinton and Yamamoto 2006) showed that administration of METH or its derivative MDMA (ecstasy) led to leakiness of the BBB in vivo. These reports proposed that breaches in the BBB permit the entry of glutamate from the blood to the brain parenchyma, thus generating a condition of glutamate excitotoxicity. However, enhanced BBB permeability was found after exposure to high concentrations of METH and the mechanism leading to the actual disruption in the BBB was not addressed in these studies. Sharma and Kiyatkin (Sharma and Kiyatkin 2009) found increased BBB permeability using Evans blue and documented brain endothelial cell abnormalities in rats (exposed to 9 mg/kg of METH). They concluded that these alterations are secondary to hyperthermia.

Using BMVEC cultures, Lee and colleagues (Lee et al 2001) showed that BMVEC respond in an inflammatory manner to METH insult by activation of NF-κB/AP-1 transcription factors and tumor necrosis factor-alpha gene upregulation; however, the investigators did not correlate these findings with BBB functional alterations (permeability, barrier integrity, or leukocyte migration). Mahajan et al. (Mahajan et al 2008) showed some marginal decreases in claudin-3 and claudin-5 mRNA levels with no change in occludin levels after 48-hr treatment with METH. The study, however, did not extend the analysis of claudin-3, claudin-5 and occludin to protein expression levels or distribution. In light of this report, it is possible that our significant decrease in claudin-5 and occludin may occur by the effects of METH on protein turnover rather than gene expression.

Toxic effects of methamphetamine depend primarily upon the dosing, the route of administration (Riviere et al 1999) and several other factors [reviewed by (Itzhak and Achat-Mendes 2004)]. In our in vivo and in vitro experiments we used doses relevant to ones seen in drug abusers. There is a significant range of concentrations in the blood of METH abusers due to pattern of administration (single dose vs. binge) and development of tolerance. METH blood levels measured in individuals detained by police in California were 2.0 μM on average but as high as 11 μM (Melega et al 2007). Controlled studies indicated that a single 260 mg dose reaches a level of 7.5 μM (Melega et al 2007). However, abusers tend to self-administer METH in binges, and with METH half-life of 12 hr such administration leads to significantly higher levels (Cho et al 2001; Harris et al 2003). Studies modeling binge pattern showed that the fourth administration of 260 mg during a single day produces blood levels of 17 μM, reaching 20 μM on the second day of such a binge (Melega et al 2007). Binge doses of 260 mg – 1 g resulted in 17–80 μM blood METH levels, and these estimates are consistent with blood levels detected after fatal injuries (Logan et al 1998; Wilson et al 1996).

In animal studies, high dose acute METH administration can lead to severe METH toxicity (Harvey et al 2000). The major lethal effect of METH exposure in animal studies is the development of hyperthermia. However, through the use of relatively continuous escalating dosing, it has been shown that animals develop tolerance to the anorectic and lethal effects of METH (Fischman and Schuster 1974). The escalating dosing regimen adapted in this study produces tolerance to the dopaminergic and serotonergic neurotoxicity which otherwise would be induced by multiple high-dose administrations of METH, while simultaneously producing stimulant effects similar to those seen in human METH abuse. To that end, using escalating non-toxic concentrations of METH, we found that in vivo administration of METH resulted in enhanced BBB permeability to the small molecular tracer Na-F. Continuous TEER measurements in vitro showed a marked decrease in TEER following METH administration, which occurred rapidly and was also sustained. Barrier compromise at the level of the TJ was evident in our morphological analysis of occludin on BMVEC monolayers exposed to the drug. The altered morphological appearance of the TJ after METH exposure was such that the TJ appeared discontinuous with formation of gaps. Expression of occludin and claudin-5 in the membranous fractions was reduced as a function of time and METH concentration, suggesting that TJ alteration may be the cause of METH-induced BBB permeability. It has been previously shown that depletion of occludin as a result of siRNA knockdown (Kevil et al 1998) or by addition of vascular endothelial growth factor decreased transendothelial resistance and increased microvascular endothelial cell permeability (Wang et al 2001).

Multiple studies suggest that METH-induced neurotoxicity involves the production of ROS and nitrogen species (such as nitrotyrosine)(Stephans and Yamamoto 1994). Therefore, we explored the possibility that ROS generation results in BBB dysfunction in METH abuse. Indeed, METH induced ROS in primary brain endothelial cells, and antioxidant prevented production of oxidative radicals and restored monolayer integrity. Furthermore, we showed that increased permeability caused by METH in vivo (mice exposed to escalating doses of drug) was partially prevented by the antioxidant, Trolox. Association of oxidative stress with enhanced endothelial permeability was documented in vitro and in vivo (reviewed in (Mehta and Malik 2006). Endothelial monolayers exposed to H2O2 (Alexander et al 2001) or hyperoxia (Phillips et al 1988) demonstrated increased transendothelial permeability of albumin. Human BMVEC treated with ROS donors or alcohol (causing ROS production) demonstrated reduced TEER, redistribution of TJ proteins (occludin, claudin-5, ZO-1) and increased permeability with antioxidant reversing these changes (Haorah et al 2005). Therefore, oxidative stress induced by diverse mechanisms results in barrier compromise.

The exact mechanism underlying ROS production after BMVEC exposure to METH is not clear. Mitochondria are common targets for oxidative species and mitochondrial dysfunction and increased energy utilization plays an important role in mediating the pro-oxidant and neurotoxic effects of METH (Bachmann et al 2009). METH treatment of cultured astrocytes increased ROS, ATP and changed the mitochondria membrane potential (Lau et al 2000). The role of oxidative stress is further supported by the findings that ROS scavengers and antioxidants attenuated the neurotoxic effects of METH (Fukami et al 2004) and resulted in significant behavior improvement associated with drug exposure (Coccurello et al 2007). Thus, further analysis would need to be performed to understand the cause(s) and origin of oxidative stress induced by METH in the brain endothelium.

Disruption of the endothelial barrier results in augmented permeability and can enhance transendothelial leukocyte migration causing subsequent tissue damage (Aghajanian et al 2008). To address this possibility, we studied migration of primary human monocytes across confluent BMVEC monolayers after pre-treatment with METH. β-chemokine (CCL2) applied on the opposite side of BBB constructs to mimic neuroinflammatory conditions [like HIVE (Persidsky et al 1999)] increases cell migration two-fold, while METH alone augmented monocyte migration by 30–50%; METH in combination with CCL2 led to synergistic 3–3.5 fold increases in monocyte passage. This finding is significant because monocytes carry HIV-1 across the BBB, and their accumulation correlates with clinical signs of cognitive decline and neuronal injury in the CNS of infected patients (Ellis et al 2007). Since antioxidants prevented barrier impairment in vitro and in vivo, we applied it to METH/CCL2 exposed BBB constructs and studied monocyte migration. Trolox diminished monocyte egress in a dose-dependent manner to levels comparable with untreated control constructs. Since the generation of ROS could activate the MLCK pathway, which in turn can cause changes to the TJ, we therefore explored the effects of METH on MLCK. Our previous work indicated that oxidative stress activates MLCK in BMVEC leading to reduced integrity of the BMVEC monolayer promoting monocyte migration across the BBB (Haorah et al 2005). Indeed, MLCK inhibition in BMVEC monolayers blocked METH/CCL2 induced monocyte migration. Activated MLCK phosphorylates MLC at Ser-19 or Ser-19/Thr-18 (Goeckeler and Wysolmerski 1995), produces endothelial cell contraction and results in barrier dysfunction in response to inflammatory mediators (Dudek and Garcia 2001). Our finding revealed that METH exposure increased the levels of phosphorylated MLC indicative of MLCK activation; conversely, antioxidant prevented this increase.

MLCK inhibition induced by oxidative stress prevents TJ modifications, MLC phosphorylation, monocyte migration and changes in transendothelial electrical resistance (Haorah et al 2005). Results of the current study suggest that many of the signaling pathways leading to BBB disruption overlap and converge on the same targets (like MLCK or TJ modifications). Our findings provide evidence that demonstrate the direct effects of METH on the BBB, along with a possible underlying mechanism for this injury. Future investigations will address how METH causes ROS generation, decreases expression of TJ proteins, identification of pathways involved in MLCK activation and whether leukocyte-endothelial interactions (such as adhesion, expression of adhesion molecules, etc.) are affected by the drug. The results of the study also indicate that METH can exacerbate BBB dysfunction, which may promote HIV-1 infection in the brain. Our results also point to a potential use for antioxidants as a therapeutic strategy to protect the brain endothelium against the effects of METH toxicity.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from NIH (DA025566, AA015913 YP, DA024979 RP). We thank Dr. Ronald Tuma for critical reading of this manuscript

Footnotes

Disclosure/Conflict of interest

The authors have no duality of interest to declare

References

- Aghajanian A, Wittchen ES, Allingham MJ, Garrett TA, Burridge K. Endothelial cell junctions and the regulation of vascular permeability and leukocyte transmigration. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6:1453–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.03087.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander JS, Zhu Y, Elrod JW, Alexander B, Coe L, Kalogeris TJ, Fuseler J. Reciprocal regulation of endothelial substrate adhesion and barrier function. Microcirculation. 2001;8:389–401. doi: 10.1038/sj/mn/7800111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avison MJ, Nath A, Greene-Avison R, Schmitt FA, Greenberg RN, Berger JR. Neuroimaging correlates of HIV-associated BBB compromise. J Neuroimmunol. 2004;157:140–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2004.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachmann RF, Wang Y, Yuan P, Zhou R, Li X, Alesci S, Du J, Manji HK. Common effects of lithium and valproate on mitochondrial functions: protection against methamphetamine-induced mitochondrial damage. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009:1–18. doi: 10.1017/S1461145708009802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowyer JF, Ali S. High doses of methamphetamine that cause disruption of the blood-brain barrier in limbic regions produce extensive neuronal degeneration in mouse hippocampus. Synapse. 2006;60:521–32. doi: 10.1002/syn.20324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowyer JF, Robinson B, Ali S, Schmued LC. Neurotoxic-related changes in tyrosine hydroxylase, microglia, myelin, and the blood-brain barrier in the caudate-putamen from acute methamphetamine exposure. Synapse. 2008;62:193–204. doi: 10.1002/syn.20478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chana G, Everall IP, Crews L, Langford D, Adame A, Grant I, Cherner M, Lazzaretto D, Heaton R, Ellis R, Masliah E. Cognitive deficits and degeneration of interneurons in HIV+ methamphetamine users. Neurology. 2006;67:1486–9. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000240066.02404.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho AK, Melega WP, Kuczenski R, Segal DS. Relevance of pharmacokinetic parameters in animal models of methamphetamine abuse. Synapse. 2001;39:161–6. doi: 10.1002/1098-2396(200102)39:2<161::AID-SYN7>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coccurello R, Caprioli A, Ghirardi O, Virmani A. Valproate and acetyl-L-carnitine prevent methamphetamine-induced behavioral sensitization in mice. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1122:260–75. doi: 10.1196/annals.1403.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz Z, Laurenzana A, Mann KK, Bismar TA, Schipper HM, Miller WH., Jr Trolox enhances the anti-lymphoma effects of arsenic trioxide, while protecting against liver toxicity. Leukemia. 2007;21:2117–27. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudek SM, Garcia JG. Cytoskeletal regulation of pulmonary vascular permeability. J Appl Physiol. 2001;91:1487–500. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2001.91.4.1487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis R, Langford D, Masliah E. HIV and antiretroviral therapy in the brain: neuronal injury and repair. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:33–44. doi: 10.1038/nrn2040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischman MW, Schuster CR. Tolerance development to chronic methamphetamine intoxication in the rhesus monkey. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1974;2:503–8. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(74)90010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flora G, Lee YW, Nath A, Hennig B, Maragos W, Toborek M. Methamphetamine potentiates HIV-1 Tat protein-mediated activation of redox-sensitive pathways in discrete regions of the brain. Exp Neurol. 2003;179:60–70. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2002.8048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukami G, Hashimoto K, Koike K, Okamura N, Shimizu E, Iyo M. Effect of antioxidant N-acetyl-L-cysteine on behavioral changes and neurotoxicity in rats after administration of methamphetamine. Brain Res. 2004;1016:90–5. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.04.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goeckeler ZM, Wysolmerski RB. Myosin light chain kinase-regulated endothelial cell contraction: the relationship between isometric tension, actin polymerization, and myosin phosphorylation. J Cell Biol. 1995;130:613–27. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.3.613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haorah J, Knipe B, Leibhart J, Ghorpade A, Persidsky Y. Alcohol-induced oxidative stress in brain endothelial cells causes blood-brain barrier dysfunction. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;78:1223–32. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0605340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris DS, Boxenbaum H, Everhart ET, Sequeira G, Mendelson JE, Jones RT. The bioavailability of intranasal and smoked methamphetamine. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2003;74:475–86. doi: 10.1016/j.clpt.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey DC, Lacan G, Tanious SP, Melega WP. Recovery from methamphetamine induced long-term nigrostriatal dopaminergic deficits without substantia nigra cell loss. Brain Res. 2000;871:259–70. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(00)02439-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HIV & drugs. Meth use develops stronger link to HIV risk. AIDS Policy Law. 2005;20:5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itzhak Y, Achat-Mendes C. Methamphetamine and MDMA (ecstasy) neurotoxicity: ‘of mice and men’. IUBMB Life. 2004;56:249–55. doi: 10.1080/15216540410001727699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kevil CG, Okayama N, Trocha SD, Kalogeris TJ, Coe LL, Specian RD, Davis CP, Alexander JS. Expression of zonula occludens and adherens junctional proteins in human venous and arterial endothelial cells: role of occludin in endothelial solute barriers. Microcirculation. 1998;5:197–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau JW, Senok S, Stadlin A. Methamphetamine-induced oxidative stress in cultured mouse astrocytes. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2000;914:146–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb05192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YW, Hennig B, Yao J, Toborek M. Methamphetamine induces AP-1 and NF-kappaB binding and transactivation in human brain endothelial cells. J Neurosci Res. 2001;66:583–91. doi: 10.1002/jnr.1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenzser G, Kis B, Bari F, Busija DW. Diazoxide preconditioning attenuates global cerebral ischemia-induced blood-brain barrier permeability. Brain Res. 2005;1051:72–80. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.05.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Logan BK, Fligner CL, Haddix T. Cause and manner of death in fatalities involving methamphetamine. J Forensic Sci. 1998;43:28–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan SD, Aalinkeel R, Sykes DE, Reynolds JL, Bindukumar B, Adal A, Qi M, Toh J, Xu G, Prasad PN, Schwartz SA. Methamphetamine alters blood brain barrier permeability via the modulation of tight junction expression: Implication for HIV-1 neuropathogenesis in the context of drug abuse. Brain Res. 2008;1203:133–48. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2008.01.093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansergh G, Shouse RL, Marks G, Guzman R, Rader M, Buchbinder S, Colfax GN. Methamphetamine and sildenafil (Viagra) use are linked to unprotected receptive and insertive anal sex, respectively, in a sample of men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Infect. 2006;82:131–4. doi: 10.1136/sti.2005.017129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin LJ, Chen K, Liu Z. Adult motor neuron apoptosis is mediated by nitric oxide and Fas death receptor linked by DNA damage and p53 activation. J Neurosci. 2005;25:6449–59. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0911-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta D, Malik AB. Signaling mechanisms regulating endothelial permeability. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:279–367. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00012.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melega WP, Cho AK, Harvey D, Lacan G. Methamphetamine blood concentrations in human abusers: application to pharmacokinetic modeling. Synapse. 2007;61:216–20. doi: 10.1002/syn.20365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Dell SJ, Marshall JF. Neurotoxic regimens of methamphetamine induce persistent expression of phospho-c-Jun in somatosensory cortex and substantia nigra. Synapse. 2005;55:137–47. doi: 10.1002/syn.20098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persidsky Y, Ghorpade A, Rasmussen J, Limoges J, Liu XJ, Stins M, Fiala M, Way D, Kim KS, Witte MH, Weinand M, Carhart L, Gendelman HE. Microglial and astrocyte chemokines regulate monocyte migration through the blood-brain barrier in human immunodeficiency virus-1 encephalitis. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:1599–611. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65476-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persidsky Y, Heilman D, Haorah J, Zelivyanskaya M, Persidsky R, Weber GA, Shimokawa H, Kaibuchi K, Ikezu T. Rho-mediated regulation of tight junctions during monocyte migration across the blood-brain barrier in HIV-1 encephalitis (HIVE) Blood. 2006a;107:4770–80. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-11-4721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Persidsky Y, Ramirez SH, Haorah J, Kanmogne GD. Blood brain barrier: Structural components and function under physiologic and pathologic conditions. J Neuroimmune Pharmacology. 2006b;1:223–36. doi: 10.1007/s11481-006-9025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phares TW, Fabis MJ, Brimer CM, Kean RB, Hooper DC. A peroxynitrite-dependent pathway is responsible for blood-brain barrier permeability changes during a central nervous system inflammatory response: TNF-alpha is neither necessary nor sufficient. J Immunol. 2007;178:7334–43. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.11.7334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips PG, Higgins PJ, Malik AB, Tsan MF. Effect of hyperoxia on the cytoarchitecture of cultured endothelial cells. Am J Pathol. 1988;132:59–72. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinton MS, Yamamoto BK. Causes and consequences of methamphetamine and MDMA toxicity. Aaps J. 2006;8:E337–47. doi: 10.1007/BF02854904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez SH, Heilman D, Morsey B, Potula R, Haorah J, Persidsky Y. Activation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARgamma) suppresses Rho GTPases in human brain microvascular endothelial cells and inhibits adhesion and transendothelial migration of HIV-1 infected monocytes. J Immunol. 2008;180:1854–65. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.3.1854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riviere GJ, Byrnes KA, Gentry WB, Owens SM. Spontaneous locomotor activity and pharmacokinetics of intravenous methamphetamine and its metabolite amphetamine in the rat. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;291:1220–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt CJ, Ritter JK, Sonsalla PK, Hanson GR, Gibb JW. Role of dopamine in the neurotoxic effects of methamphetamine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1985;233:539–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekine Y, Ouchi Y, Sugihara G, Takei N, Yoshikawa E, Nakamura K, Iwata Y, Tsuchiya KJ, Suda S, Suzuki K, Kawai M, Takebayashi K, Yamamoto S, Matsuzaki H, Ueki T, Mori N, Gold MS, Cadet JL. Methamphetamine causes microglial activation in the brains of human abusers. J Neurosci. 2008;28:5756–61. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1179-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma HS, Kiyatkin EA. Rapid morphological brain abnormalities during acute methamphetamine intoxication in the rat: an experimental study using light and electron microscopy. J Chem Neuroanat. 2009;37:18–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stamatovic SM, Dimitrijevic OB, Keep RF, Andjelkovic AV. Protein kinase Calpha-RhoA cross-talk in CCL2-induced alterations in brain endothelial permeability. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:8379–88. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513122200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephans SE, Yamamoto BK. Methamphetamine-induced neurotoxicity: roles for glutamate and dopamine efflux. Synapse. 1994;17:203–9. doi: 10.1002/syn.890170310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tata DA, Yamamoto BK. Interactions between methamphetamine and environmental stress: role of oxidative stress, glutamate and mitochondrial dysfunction. Addiction. 2007;102(Suppl 1):49–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.01770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Dentler WL, Borchardt RT. VEGF increases BMEC monolayer permeability by affecting occludin expression and tight junction assembly. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2001;280:H434–40. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.1.H434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weksler BB, Subileau EA, Perriere N, Charneau P, Holloway K, Leveque M, Tricoire-Leignel H, Nicotra A, Bourdoulous S, Turowski P, Male DK, Roux F, Greenwood J, Romero IA, Couraud PO. Blood-brain barrier-specific properties of a human adult brain endothelial cell line. Faseb J. 2005;19:1872–4. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3458fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JM, Kalasinsky KS, Levey AI, Bergeron C, Reiber G, Anthony RM, Schmunk GA, Shannak K, Haycock JW, Kish SJ. Striatal dopamine nerve terminal markers in human, chronic methamphetamine users. Nat Med. 1996;2:699–703. doi: 10.1038/nm0696-699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yatin SM, Miller GM, Norton C, Madras BK. Dopamine transporter-dependent induction of C-Fos in HEK cells. Synapse. 2002;45:52–65. doi: 10.1002/syn.10084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]