Abstract

Prenatal testosterone (T) treatment leads to polycystic ovarian morphology, enhanced follicular recruitment/depletion, and increased estradiol secretion. This study addresses whether expression of key ovarian genes and microRNA are altered by prenatal T excess and whether changes are mediated by androgenic or estrogenic actions of T. Pregnant Suffolk ewes were treated with T or T plus the androgen receptor antagonist, flutamide (T+F) from d 30 to 90 of gestation. Expression of steroidogenic enzymes, steroid/gonadotropin receptors, and key ovarian regulators were measured by RT-PCR using RNA obtained from fetal ovaries collected on d 65 [n = 4, 5, and 5 for T, T+F, and control groups, respectively] and d 90 (n = 5, 7, 4) of gestation. Additionally, fetal d 90 RNA were hybridized to multispecies microRNA microarrays. Prenatal T decreased (P < 0.05) Cyp11a1 expression (3.7-fold) in d 90 ovaries and increased Cyp19 (3.9-fold) and 5α-reductase (1.8-fold) expression in d 65 ovaries. Flutamide prevented the T-induced decrease in Cyp11a1 mRNA at d 90 but not the Cyp19 and 5α-reductase increase in d 65 ovaries. Cotreatment with T+F increased Cyp11a1 (3.0-fold) expression in d 65 ovaries, relative to control and T-treated ovaries. Prenatal T altered fetal ovarian microRNA expression, including miR-497 and miR-15b, members of the same family that have been implicated in insulin signaling. These studies demonstrate that maternal T treatment alters fetal ovarian steroidogenic gene and microRNA expression and implicate direct actions of estrogens in addition to androgens in the reprogramming of ovarian developmental trajectory leading up to adult reproductive pathologies.

Adverse in utero environment, including exposure to abnormal nutritional, environmental, metabolic, and hormonal insults, can alter the developmental trajectory of the fetus and lead to the adult onset of disease (1). Developmental insults have been documented to disrupt cardiovascular, metabolic, and reproductive systems in numerous species (i.e. human, monkey, sheep, rodent) (1–4). For example, female sheep fetuses exposed to excess testosterone (T) manifest low birth weight (5), intrauterine growth restriction (6), postnatal catch-up growth (5), reproductive neuroendocrine defects (7–12), ovarian defects (6, 13–17), oligo/anovulation (12, 14), luteal compromise (14, 15), insulin resistance (18), and hypertension (19), with many of these characteristics being similar to those observed in women with polycystic ovarian syndrome (20).

The metabolic and reproductive dysfunctions observed in adult female sheep in response to excess fetal T exposure demonstrate the important role steroid hormones play in reprogramming of fetal organ differentiation. At the ovarian level, prenatal T treatment leads to polycystic ovaries (13) and increases follicular recruitment (6, 17) and persistence (14, 15). Sheep prenatally treated with the nonaromatizable androgen, dihydrotestosterone (DHT) fail to produce a multifollicular phenotype (13) or follicular persistence (15), thus suggesting these outcomes are programmed via aromatization of T to estrogen. A comprehensive understanding of the early perturbations underlying reprogramming of the adult phenotype in response to excess gestational T is essential to develop interventions aimed toward prevention. Immunohistochemical studies focusing on few select proteins have found that phenotypic changes are preceded by increased expression of proteins for androgen receptor [AR (16)] and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ [PPARγ (21)] as early as fetal d 90 in prenatal T-treated sheep, thus pointing to involvement of steroidogenic and metabolic signaling pathways. These predictions are also supported by findings of elevated estradiol and insulin levels in prenatal T-treated females (12, 18). Recent studies implicate microRNA (miRNA) as key regulators in changing gene expression in developing tissues and organs (for review, see Ref. 22), with an abundance of miRNA in newborn and adult mice ovaries (23–28). Our recent studies have found that miRNA play key roles in gonadotropin-mediated regulation of ovarian function (29, 30). The aim of this study therefore was to gain an understanding of early perturbations in the ovarian transcriptome, specifically the expression of steroidogenic enzymes, steroid hormone receptors, gonadotropin receptors, and key ovarian regulators and identify changes in fetal ovarian miRNA expression in response to prenatal T treatment.

Materials and Methods

Animals, prenatal treatments, and tissue collection

All procedures were approved by the University Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Michigan. Two- to 3-yr-old Suffolk ewes were purchased locally and group fed 0.5 kg of shelled corn and 1.0–1.5 kg of alfalfa hay/ewe per day (2.31 Mcal/kg of digestible energy). The day of mating was determined by visual confirmation of paint markings left on the rumps of ewes by the raddled rams. The diet meets the nutrient requirements for sheep defined by the National Research Council (Committee on the Nutrient Requirements of Small Ruminants National Research Council, Nutrient Requirements of Small Ruminants, Sheep, Goats, Cervids, and New World Camelids, Washington, DC) (5). Aureomycin crumbles (chlortetracycline: 250 mg per ewe per day) were administered to reduce abortion from diseases such as Campylobacter and Chlamydia. Breeder animals assigned to generate control, T-treated, and T plus AR antagonist (i.e. flutamide)-treated fetuses were blocked by maternal weight, body score, age, and animal providers. Details of T and flutamide treatments and descriptions of phenotypic effects on offspring (i.e. ovarian phenotype, neuroendocrine defects, intrauterine growth restriction, and masculinization of external genitalia) have been published previously (5–21, 31). Gestational T treatment consisted of twice-weekly im injections of 100 mg T propionate (Sigma-Aldrich Corp., St. Louis, MO) in cottonseed oil (2 ml volume) from d 30 to d 90 of gestation (term ∼ 147 d) (5). AR antagonist treatment consisted of daily sc injections of 15 mg/kg flutamide [Sigma-Aldrich (31)]. Control ewes received the same volume of vehicle. The concentrations of T achieved in the mother and female fetus during gestational T treatment are comparable with that of the adult males and the early T rise seen in male fetuses, respectively (32). T treatment also increased fetal levels of estradiol (32), suggestive of the potential for the involvement of both androgenic and estrogenic pathways in programming adult dysfunction.

Collection of fetal ovaries

Fetal ovaries were collected from control and T-treated dams on d 64–66 and d 87–90 (range) of gestation (referred as d 65 and d 90, respectively, hereafter). All dams were sedated with 20–30 ml pentobarbital iv (Nembutol Na solution; 50 mg/ml; Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, IL) and subsequently maintained under general anesthesia (1–2% halothane; Halocarbon Laboratories, River Edge, NJ). The gravid uterus was exposed through a midline incision and the uterine wall incised. Dams were administered a barbiturate overdose (Fatal Plus; Vortech Pharmaceuticals, Dearborn, MI) and fetuses removed for tissue harvest. Fetal ovaries were removed from d 65 and d 90 control, prenatal T and T plus flutamide fetuses, weighed, washed with PBS, quick frozen, and stored at −80 C until processing. One ovary from one female offspring of each dam (the mother was the experimental unit) from d 65 and d 90 control (n = 5 and 4, respectively), prenatal T (d 65, n = 4; d 90, n = 5) and T plus flutamide (d 65, n = 5; d 90, n = 7)-treated animals were used for gene expression studies.

Quantitative RT-PCR

mRNA analysis

Fetal ovarian RNA was isolated with Trizol, per the manufacturer's instruction and assessed for quality using the Agilent Bioanalyzer Nano Chip (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). All RNA samples had sharp 18S and 28S peaks and RNA integrity numbers greater than 8.0, indicating high-quality RNA. Total RNA (250 ng) isolated from whole ovarian fetal tissue was reverse transcribed (QIAGEN miScript System, Valencia, CA) per the manufacturer's instruction. The resulting cDNA was amplified by quantitative RT-PCR using forward and reverse primers designed to ovine or bovine sequences (Supplemental Table 1, published on The Endocrine Society's Journals Online web site at http://endo.endojournals.org) and Power Sybr Green (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA) with the Applied Biosystems 7900HT real-time system. Analysis of genes included enzymes in steroidogenic pathway [steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR), cholesterol side chain cleavage enzyme (Cyp11a1), 3β1-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3β1HSD), 3β2HSD, Cyp17, 17β-HSD, Cyp19, steroid-5-α-reductase (SRD5A1), and ferredoxin-1 (FDX1)], steroid receptors [AR, estrogen receptors [estrogen receptor α (ESR1); estrogen receptor β (ESR2)], progesterone receptor (PGR)], gonadotropin receptors [FSH receptor (FSHR) and LH receptor (LHR)], and key regulators of ovarian development and function [growth differentiation factor 9 (GDF9) and cyclin D2 (CCND2)]. Analysis of expression of insulin-related signaling genes included IGF-I (IGFI), IGF-I receptor (IGFR1), insulin receptor (IR), insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS1), IRS2, mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR), protein kinase B (Akt), phosphoionositide-3-kinase (PI3K), glucose transporter type 4 (Glut4), and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPARα). All assays used the standard cycling conditions (50 C for 2 min, 95 C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 95 C for 15 sec and 60 C for 1 min) in addition to a dissociation curve to determine product melting temperature insuring presence of a single amplicon. The small RNA U6 was used for normalization and a relative standard curve was analyzed for each specific gene target. All data were analyzed by comparing the relative amount of gene product to the relative amount of U6.

miRNA analysis

To identify miRNA expressed in fetal ovarian tissue, total RNA from fetal d 90 sheep was hybridized to the multispecies Affymetrix GeneChip miRNA Array (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). The Affymetrix miRNA arrays were background corrected, normalized, and gene level summarized using the robust multichip average procedure (33). Fold change statistics for miRNA were calculated by taking the linear contrast between the least square means of the (log) treatment and (log) control groups and backtransforming the result to a linear scale (this is the ratio of the geometric mean of the treatment samples to the geometric mean of the control samples). Corresponding significance scores (P values) were calculated based on the t statistic of the linear contrast. The tissues were assayed in biological quadruplicates.

For confirming changes in specific miRNA expression from array data, total RNA (25 ng) was reverse transcribed (miRCURY LNA universal reverse transcriptase; Exiqon, Vedback, Denmark) per the manufacturer's instruction. The resulting cDNA was amplified and quantified for miR-497, miR-10a, miR-150, miR-29a, and miR-15b using LNA primer assays (Exiqon) and Sybr Green (Exiqon). All assays were performed on the Applied Biosystems 7900HT real-time system with the following cycling conditions: 95 C for 10 min, 40 cycles of 95 C for 10 sec, and 60 C for 1 min and a dissociation curve to determine product melting temperature. The U6 primer assay (Exiqon) was used for normalization and a relative standard curve was analyzed for each miRNA. All data were analyzed by comparing the relative amount of gene product to the relative amount of U6.

Bioinformatic analysis was conducted on all miRNA differentially expressed between control and T or control and T+flutamide treated animals using TargetScan 5.1 (www.targetscan.org) to identify putative mRNA targets. Analysis of mRNA targets focused on insulin signaling molecules, steroid receptors/enzymes, and lipid metabolic hormones as well as key known ovarian regulatory genes. A comprehensive literature based analysis was also conducted on all differentially expressed miRNA. Those miRNA that were linked to diabetes, insulin signaling, steroid receptor action, steroidogenesis, ovarian function, sexual differentiation, and lipid metabolism were selected from the inclusive lists.

Statistical analysis

All hormone receptor and steroidogenic enzyme mRNA expression data generated by quantitative RT-PCR was log transformed and analyzed by two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc test (Prism, version 4; GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Quantitative RT-PCR data relating to expression of miRNA was log transformed and analyzed by ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc test (Prism). A P < 0.05 was considered significant, unless otherwise noted.

Results

Steroidogenic enzymes and related genes

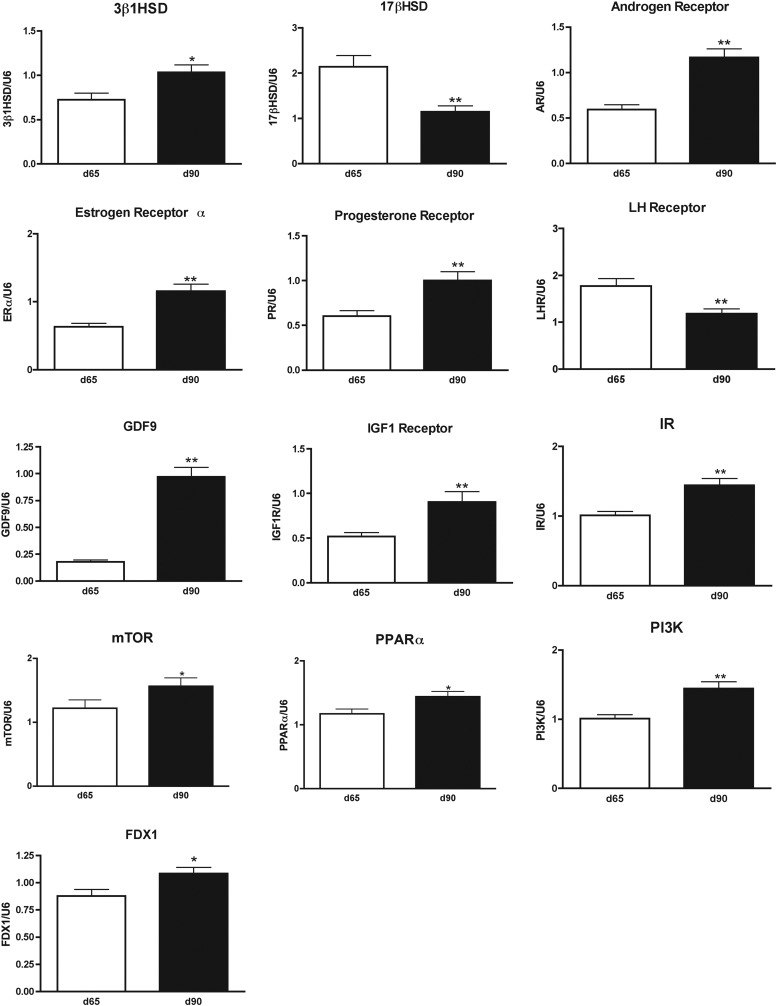

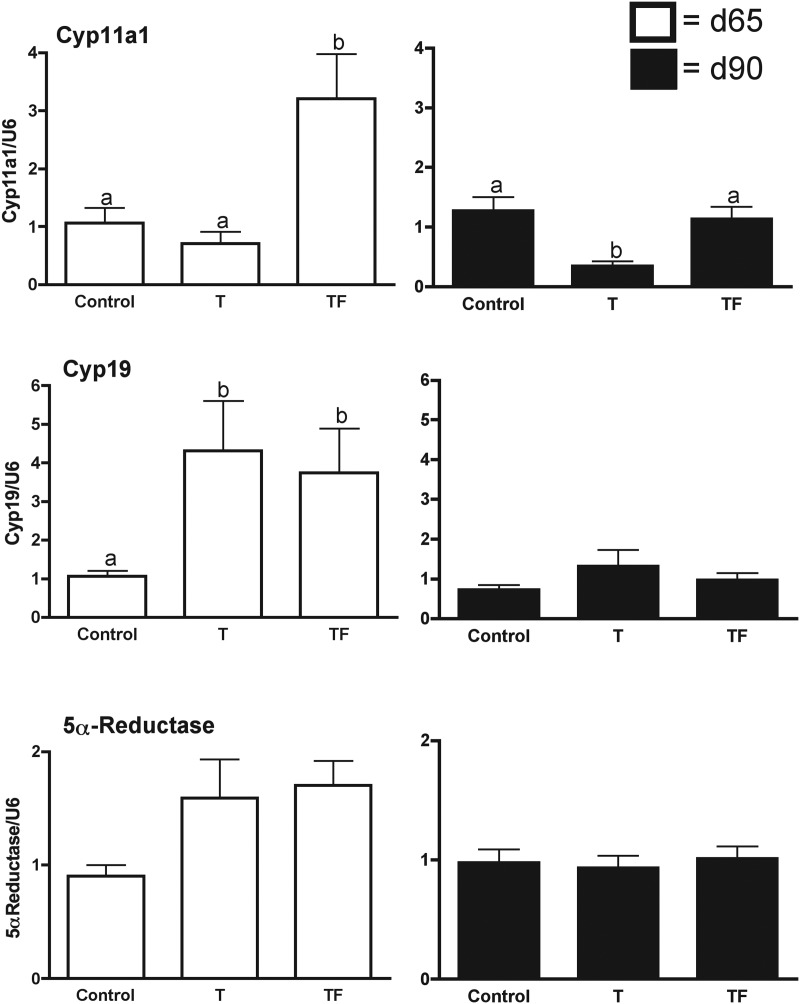

An age-dependent increase in 3β1HSD (P < 0.05) and FDX-1, and a decrease in 17β1HSD (P < 0.001) was evident between fetal d 65 and d 90 (Fig. 1). There was no age effect in mRNA expression levels for 3β2HSD, Cyp17, Cyp19, 5α-reductase, or StAR (data not shown). Gestational T treatment had a fetal age-specific effect on expression of Cyp11a1 mRNA, the enzymatic rate-limiting step of steroidogenesis (Fig. 2). Prenatal T treatment decreased Cyp11a1 expression in fetal d 90 but not fetal d 65. In contrast, cotreatment with T plus AR antagonist increased expression of Cyp11a1 in fetal d 65 ovaries, relative to age-matched T-treated and control fetuses. Furthermore, the AR antagonist cotreatment prevented the decrease in expression associated with T treatment alone in the d 90 fetal ovaries.

Fig. 1.

Fetal ovarian genes (mRNA) that exhibit changes in expression between d 65 (white bars) and d 90 (black bars) of gestation as determined by quantitative RT-PCR of mRNA from whole ovarian tissue of control, T-treated, and T plus AR antagonist-treated (TF), female fetuses. Because no treatment effects were observed, the data for all treatment groups were pooled by age. Results are expressed as mean ± sem. Asterisks denotes an age effect (*, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01).

Fig. 2.

Fetal ovarian steroidogenic enzyme genes (mRNA) that are altered by prenatal T (T) and T plus AR antagonist (TF) treatment as determined by quantitative RT-PCR of mRNA from fetal d 65 (white bars) and fetal d 90 (black bars) whole ovarian tissue. Treatment effects on mRNA expression were determined by two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc tests. Differing superscripts indicate significant differences (P < 0.05). Note for 5α-reductase, the T and TF females showed a tendency to be higher compared with controls (P = 0.0795).

Maternal T as well as T plus AR antagonist treatment increased expression of mRNA for Cyp19 in d 65 but not d 90 ovaries (P < 0.05; Fig. 2), relative to controls. Maternal T and T plus AR antagonist treatment also tended (P = 0.0785) to increase expression of mRNA for 5α-reductase, which converts T to DHT, on fetal d 65 but not d 90. Prenatal T or T plus AR antagonist did not alter the expression of mRNA for StAR and other steroidogenic enzymes (3β1HSD, 3β2HSD, 17β1HSD, or Cyp17) at either time points.

Hormone receptors

An age-related increase (P < 0.01; ∼2-fold) in expression of AR, ESR1 (ERα), and PGR mRNA was evident between d 65 and d 90 (Fig. 1). In contrast, ESR2 expression was similar between fetal d 65 and d 90. Maternal T or T plus AR antagonist failed to alter expression of any of the steroid hormone receptor mRNA (AR, PGR, ESR1, and ESR2). In terms of the gonadotropin receptors, there was a decrease in expression of LHR (P < 0.01) from fetal d 65 to d 90 (Fig. 1), whereas FSHR levels tended (P = 0.057, 1.74-fold) to increase between d 65 and d 90 (data not shown). Gestational T or T plus AR antagonist treatment failed to alter expression pattern of the gonadotropin receptors, LHR, and FSHR.

Ovarian regulatory factors

Increased expression between fetal d 65 and d 90 was observed for GDF9 (P < 0.01, Fig. 1), whereas cyclin D2 did not change in response to age (not shown). Maternal T treatment, with and without AR antagonist treatment, did not alter expression of any of the ovarian regulatory genes examined.

Insulin-related genes

Age-dependent increase in expression of IGF-I receptor (P < 0.01), IR, mammalian target of rapamycin, and PPARα, and PI3K were observed between d 65 and d 90 of gestation (Fig. 1). Conversely, IGF-I, IRS1, IRS2, Akt, and glucose transporter exhibited no change in expression with respect to age (not shown). Maternal T treatment, with and without AR antagonist treatment, did not alter expression of any of the insulin-related regulatory genes.

MicroRNA

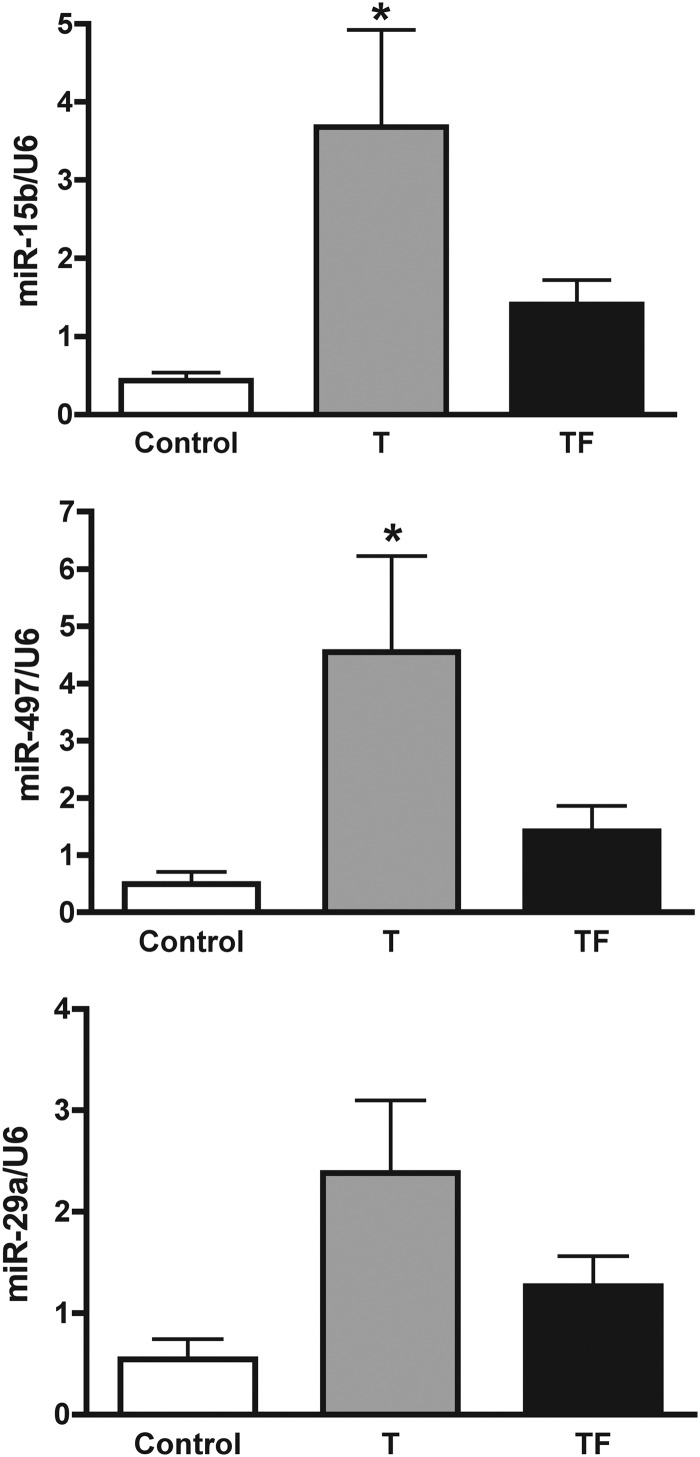

Comparison of control vs. T-treated ovaries using a multispecies miRNA microarray identified 31 up-regulated (>1.5-fold) and 18 down-regulated (>1.5-fold) miRNA (Supplemental Table 2) in d 90 fetal ovaries. Comparison of control vs. T plus AR antagonist treated ovaries identified 21 miRNA up-regulated (>1.5-fold) and 16 miRNA down-regulated (>1.5-fold; Supplemental Table 2). A total of 35 miRNA were differentially expressed between T and T plus AR antagonist-treated fetal d 90 ovaries (Supplemental Table 2) compared with controls. Examination of the mRNA predicted (TargetScan) to be targets of the differentially expressed miRNA indicated a large number (25) of miRNA had putative insulin-signaling target transcripts (Table 1). Of these 25 miRNA with predicted insulin-signaling target mRNAs, 15 have been associated with insulin signaling/diabetes in cited papers (Table 1). Four additional miRNA were included in Table 1, based on their prior association (literature based) with ovarian tissue. Interestingly, of the 29 miRNA included in Table 1 that were differentially expressed in control, T and T+F treated animals, 20 miRNA have previously been linked (literature) to steroid expression, ovarian regulation, sexual differentiation, or fetal programming (Table 1). Increased expression of miR-15b and miR-497 in fetal d 90 ovaries in response to gestational T treatment was validated by quantitative RT-PCR (Fig. 3). Additionally, miR-29a tended to increase (P = 0.0613) in the T (2.38 ± 0.71, mean ± sem) compared with control (0.54 ± 0.20) ovaries.

Table 1.

microRNA differentially expressed in control vs. T- or T plus flutamide-treated fetal ovine ovaries

| miRNA | C vs. T FC | C vs. TF FC | Functional analysis literature based$ | Predicted targets (Targetscan) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| miR-497 | 3.83 | 3.71 | Type 2 diabetes rat [miR-15b/497 family (1) | PAPPA, IR, GHR, IGF2R, IRS2, IGF1R, furin |

| miR-29a | 2.98 | Diabetes/insulin signaling (1–5), FSH regulated (6) | IGF1, INSIG1, leptin | |

| miR-192 | 2.19 | Diabetic neuropathy (4, 7, 8) | IGF1 | |

| miR-24-2* | 2.12 | Diabetes (9), Insulin signaling (10), bovine ovary (11) | INSIG1, PPARa, Furin, IGFBP5, IGF2BP2 | |

| miR-15b | 2.06 | 2.93 | Type 2 diabetes rat FSH (1), regulated in ovary (6) | PAPPA, IR, GHR, IGF2R, IRS2, IGF1R, furin |

| miR-101 | 1.90 | AR regulated (12) | PGRMC2, PPARa | |

| miR-212 | 1.87 | LH regulated in ovary (13) | ||

| miR-451 | 1.85 | Sex dependent in liver (14) | ||

| miR-186 | 1.82 | Type 1 diabetes (15) | INSM1, LEPR, IGF1, IGF1R | |

| miR-672 | 1.82 | Mouse ovary (16) | IGF1R | |

| miR-7 | 1.67 | Insulin signaling (17, 18) | IRS2, IRS1, IGF1R, PAPPA | |

| miR-30b-5p | 1.58 | Estrogen regulated (19) | LEPR, IGF2R, INSIG2, IRS1, IRS2, LDLR, IGF1R, IGF1 | |

| miR-22* | 1.52 | Fetal ovine gonad (20), androgen regulated (21), represses ESR1 (22) | ESR1, GHRHR, PTGS1, IGF2BP1, furin | |

| miR-378 | −4.13 | Lipid/fatty acid metabolism (23), regulates estrogen production (24) | ||

| miR-760 | −2.80 | Estrogen regulated (25) | IR | |

| miR-10a | −2.76 | −3.36 | Androgen regulated (26), ovary (27) | PPARa |

| miR-182 | −2.71 | Insulin signaling (10), ovary (27) | INSIG1, IGF2BP1 | |

| miR-129* | −2.22 | Diabetes (28) | IGF1, GHR, ESR1, INSIG2 | |

| miR-132 | −1.82 | LH regulated in ovary (13) | ||

| miR-223 | −1.69 | Diabetes (9) | IGF1R | |

| miR-363 | 4.50 | Sex differentiation (29) | PTGER4, IRS2, INSIG1 | |

| miR-20b | 3.24 | Diabetes (9), ESR1 regulated (30) | PPARa, LDLR, IGF2BP1, ADIPOR2, PPARd | |

| miR-330 | 1.71 | Fetal programming (31) | IGF2BP1 | |

| miR-29c | 1.64 | Diabetic neuropathy (32), diabetes (2) | IGF1, INSIG1, leptin | |

| miR-29b | 1.62 | Diabetes (2, 9), sex dependent in liver (14) | IGF1, INSIG1, leptin | |

| miR-191* | 1.56 | Diabetes (9) | ||

| miR-101a* | 1.53 | AR regulated (12) | PGRMC2, PPARa | |

| miR-105 | 1.52 | Human ovary (27) | ||

| miR-133a | −1.85 | Insulin signaling (33, 34) | IR, IGF1R |

C, Control; ER, estrogen receptor; FC, Fold change; TF, testosterone + flutamide.

References for table are included in the Supplemental Online Materials.

Fig. 3.

Fetal ovarian miRNA expression affected by prenatal T (T) and T plus AR antagonist (TF) treatment as determined by quantitative RT-PCR of miRNA from whole ovarian tissue from fetal d 90. Treatment effects on expression of miRNA were determined by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc tests. Asterisks indicate significant differences from control (P < 0.05). Note for miR-29a (bottom panel) the T group showed a tendency to be higher than controls (P = 0.0613).

Discussion

Findings from this study demonstrate that prenatal T treatment alters the developmental expression of key ovarian steroidogenic enzymes and miRNA during fetal life. These early developmental changes likely contribute toward the ovarian disruption and increased estradiol release seen in the adult prenatal T-treated females. Comparison of mRNA and miRNA expression data between prenatal T and prenatal T plus AR antagonist treated females provide evidence that some of the regulation is mediated via androgenic programming and others likely by estrogenic programming.

Key ovarian genes expressed by fetal d 65 ovary

Our studies show that expression of 3βHSD, essential for the biosynthesis of steroids, namely progesterone, androgens, and estrogens, is evident before primordial follicular differentiation (34). Earlier studies have found cells within cell streams and rete cell tubules contain 3βHSD (35), suggesting that somatic cells destined to differentiate into granulosa/theca cells are likely the sites of this expression (36). The findings that d 65 fetal ovary expresses Cyp19 (aromatase) and Cyp11a1 are also in agreement with earlier findings (35). In addition, for the first time, our findings document that fetal d 65 sheep ovary expresses 5α-reductase and 17βHSD. Expression of gonadotropin receptors (LHR and FSHR), steroid receptors (AR, ESR1, and ESR2), and GDF9 mRNA in the d 65 fetal ovary is also consistent with previous findings (37–39). Expression of PGR in our study at d 65 and not until d 75 in an earlier study (38) may relate to differences in sensitivity of the approaches used.

Changes in expression of ovarian genes from fetal d 65 to d 90

The increase in expression of 3βHSD, a new finding, and decrease in 17βHSD in d 90 fetal ovary relative to fetal d 65 ovary corresponds to the time when primordial follicular differentiation occurs. The decrease in 17βHSD seen in d 90 ovary is expected because overexpression would lead to masculinization of external and internal genitalia in female fetuses (40). The direction of change in AR, PGR, and ESR1 (increase) seen between d 65 and d 90 parallels previous findings (38). The dichotomy in ESR1 and ESR2 expression with ESR1 increasing, but not ESR2, likely reflects the roles they play at this developmental stage. The increase in ESR1 between d 65 and d 90 coincides with continued formation of ovigerous cords and ovarian tissue remodeling (34). The increase in mRNA expression from d 65 to d 90 of FDX1, a key step in P450 enzymes activity including Cyp11a1, Cyp17, and Cyp19 (41), supports increased steroidogenic ability of the ovary. The increase in expression of GDF9 and IGF-I receptor between d 65 and d 90 likely plays a role in advancing follicular differentiation and establishing oocyte somatic cell communication.

Effects of gestational T treatment on fetal ovarian gene expression

Prenatal T treatment had fetal age-specific but opposing effects on the expression of Cyp11a1 and Cyp19, with the effect on Cyp11a1 evident at fetal d 90, and Cyp19 at fetal d 65. Prenatal T-induced increase in Cyp19 is in line with increased estradiol levels seen in fetal circulation (32). This suggests that the fetal ovary also contributes toward the aromatization of T to estradiol during the T treatment period. These changes differ from those of the Scottish Greyface sheep (37), which may reflect timing of exposure to T (starting d 30 in present study and d 60 in the Hogg et al. study) or breed differences.

A trend for an increase in 5α-reductase was also evident in d 65 T-treated fetuses, a time point when a significant increase in Cyp19 was evident, supporting the possibility of conversion of T to both estradiol [increased in d 65 female fetuses (32)] and DHT. These changes appear to be mediated by estrogenic actions stemming from aromatization of T because cotreatment with T and an AR antagonist resulted in similar changes in Cyp19 (significant increase) and 5α-reductase (tendency for an increase) expression. The finding that such changes are evident only at d 65 but not at d 90 suggests vulnerable periods for susceptibility to reprogramming ovarian function; prenatal T treatment from d 30 to d 90 but not from d 60 to d 90 leads to polycystic ovarian phenotype (42).

The decrease in Cyp11a1 mRNA expression at d 90 also occurred in Scottish Greyface sheep (d 60–90 of gestation) (37). This reduction in Cyp11a1 mRNA expression in the T group, if evident at protein level, would reduce conversion of cholesterol to the steroid precursor pregnenolone and consequent downsteam effect on steroid production. A recent study found mutation in Cyp11a1 gene resulted in phenotypes ranging from classic lipoid congenital adrenal hyperplasia to a nonclassic phenotype (43). The paradoxical increase in Cyp11a1 only in T plus AR antagonist-treated but not T-treated d 65 ovaries suggests that the AR antagonist, flutamide, may have direct effects, such as previously reported for rats (44). Alternatively, these findings support the need for a threshold level of endogenous androgen action, which flutamide cotreatment overcomes. Failure of AR antagonist cotreatment to overcome the effects of T treatment on Cyp11a1 at fetal d 90 supports estrogenic mediation.

The lack of effect of T treatment on mRNA expression of AR does not parallel our findings of increased AR protein expression in the stroma and granulosa cells of fetal d 90 ovaries (16). Such differences may relate to differences in the impact of T at the mRNA and protein level or alternatively that monitoring changes in whole ovary dilutes detection of cell-specific changes. The lack of changes in ESR2 and PGR mRNA expression parallel findings with immunocytochemical approaches (16).

Effects of gestational T treatment on fetal ovarian miRNA expression

MicroRNA, short noncoding RNA that mediate gene expression posttranscriptionally, regulate gene expression important in cellular differentiation and tissue development (30, 45). They have been identified in the fetal ovary of the sheep (46) and cow (47) as well as shortly after birth in the mouse (24, 27). Evidence exists in support of T-regulating expression of distinct miRNA via genotropic and nongenotropic mechanisms in the mouse liver (48, 49). Our finding of 31 up-regulated and 18 down-regulated miRNA in the d 90 gestational T-treated ovaries is consistent with this premise. The finding that 35 miRNA were differentially expressed between T and T plus AR antagonist-treated fetal d 90 ovaries indicate some of the mediation occurs via androgenic and others estrogenic pathways. A recent study found several miRNA to be differentially expressed in fetal d 42 and d 75 ovary and testes (46). Importantly, several of these expressed miRNA are predicted to target genes such as ESR1, CYP19, and Sry-related-HMG Box (SOX), which are known to be important in gonadal development. Several of the miRNA differentially expressed in our gestational T-treated ovaries (see Table 1) have been shown to be estrogen or androgen regulated in other studies (see references associated with Table 1). In our study miR-378 exhibited the greatest decrease in expression in response to the prenatal T treatment; interestingly, this miRNA was recently shown to posttranscriptionally regulate granulosa cell aromatase levels (50). Furthermore, down-regulation of miR-378 is consistent with the increase in aromatase mRNA expression observed in the d 65 ovaries from T-treated dams.

A common theme identified from comprehensive literature and bioinformatic analysis was that many of the differentially expressed miRNA are linked to regulation of insulin signaling and metabolism (Table 1). Interestingly, two miRNA up-regulated by T, miR-497 and miR-15b, share similar seed sequences, or bases 2–9 of the miRNA that are thought to be the primary bases that interact with the 3′ untranslated region of the mRNA target. Bioinformatic analysis of putative targets for family members, miR-497 and miR-15b identified a number of members of the insulin signaling pathway including insulin receptor, IRS2, IGF1R, IGF2R, and pregnancy-associated plasma protein A/pappalysin1, which cleaves IGF binding protein to regulate insulin signaling. miRNA-15b was previously identified as being regulated by FSH in the ovary (51) and differentially expressed in rat models of diabetes (52). Thus far, none of the putative targets of miR-497 have been validated functionally, and further study is needed to elucidate whether it impacts insulin signaling. Prediction of potential targets for miR-29a also revealed members of the insulin signaling pathway (IGF-I, insulin induced gene 1, INSIG1), and miR-29a is up-regulated in patients with diabetes (53). Moreover, miR-29a was recently shown to regulate the expression of p85 subunit of and PI3K, preventing insulin-mediated activation of Akt and downstream genes involved in gluconeogenesis (52, 54, 55).

Examination of mRNA expression of several of these genes in fetal ovarian tissues failed to detect loss or gain in mRNA expression for this entire class of insulin regulated genes. Our studies, however, examined only mRNA expression, and although evidence exists that miRNA decrease levels of their specific target transcripts approximately 20% (56), a large number of studies implicate blockade of translation as the predominant miRNA mediated posttranscript regulatory mechanism in animals (57, 58). In-depth analyses of protein levels within fetal ovarian tissues of T-treated ewes will address whether any of the putative miRNA-regulated, insulin-related genes are regulated by the differentially expressed miRNA. Although the targets of the specific miRNA remains to be determined at the ovarian level, the predicted targets are consistent with steroidal and metabolic perturbations in the gestational T-treated fetuses.

Functional significance

Because the sheep genome is not completely characterized and annotated information is not available, a global screen using arrays is not optimal to get a more comprehensive assessment of changes in transcriptome. As such, we chose to target our investigation to several critical regulatory genes implicated in ovarian differentiation. Identified changes are biologically relevant and link well with subsequently observed functional changes. The increase in Cyp19 seen during fetal life and the increase in estradiol found in adult prenatal T-treated females (12) substantiate programming of adult phenotype early in life. Similarly, the increase in 5α-reductase activity seen in T fetuses may form the basis for the increased expression in 5α-reductase in granulosa cells of polycystic ovarian syndrome ovaries (59), the reproductive and metabolic phenotype of whom the prenatal T-treated sheep recapitulates (42). Because the mechanisms regulating ovarian differentiation and follicular activation/recruitment/persistence are poorly understood, defining the relative role of early changes in 5α-reductase, Cyp19, and Cyp11a1 in reprogramming ovarian dysfunction and identifying additional mediators is an exciting avenue for future research.

Changes in miRNA expression after prenatal T exposure, in concert with their reported involvement in cellular differentiation and tissue development, suggest that miRNA are likely to play a role in ovarian remodeling. Similarly, linkage of several of the differentially regulated miRNA to insulin signaling and ovarian steroidogenesis bring functional relevance to these findings in view of the functional hyperandrogenism and insulin resistance manifested by the adult prenatal T-treated females (42). Furthermore, given the general importance of this gene regulatory system and its disruption in type 2 diabetes (60), these miRNA may be involved in long-term alteration of insulin sensitivity at the ovarian level in prenatal T-treated females due to reprogramming of the fetal ovary. Establishment of specific function attributed to each miRNA impacted by prenatal T excess would require site-specific targeted knockdown or functional testing in vitro using ovaries generated from control and prenatal T-treated females, a goal for the future. Nonetheless, considering that studies relative to miRNA are in their infancy, the findings that prenatal T excess modulates expression of miRNA implicated in insulin and steroidogenic pathway very early during fetal life are novel, in view of the modulatory role insulin and steroids play in establishing ovarian sensitivity and differentiation, respectively.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Mr. Douglas Doop for his expert animal care and facility management; and Ms. Carol Herkimer and Mr. James Lee for assistance with prenatal treatments and procurement of tissues.

This work was supported by U.S. Public Health Service Grant P01 HD044232 (to V.P.) and the Hall Family Foundation (to L.K.C.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- Akt

- Protein kinase B

- AR

- androgen receptor

- DHT

- dihydrotestosterone

- ESR1

- estrogen receptor α

- ESR2

- estrogen receptor β

- FDX1

- ferredoxin-1

- FSHR

- FSH receptor

- GDF9

- growth differentiation factor 9

- 3β1HSD

- 3β1-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase

- 3β2HSD

- 3β2-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase

- 17β-HSD

- 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase

- IGFR1

- IGF-I receptor

- IR

- insulin receptor

- IRS1

- insulin receptor substrate 1

- IRS2

- insulin receptor substrate 2

- LHR

- LH receptor

- miRNA

- microRNA

- PGR

- progesterone receptor

- PPAR

- peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor

- PI3K

- phosphoinositide-3-kinase

- StAR

- steroidogenic acute regulatory protein

- T

- testosterone.

References

- 1. Barker DJ. 1990. The fetal and infant origins of adult disease. BMJ 301:1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Abbott DH, Dumesic DA, Levine JE, Dunaif A, Padmanabhan V. 2006. Animal models and fetal programming of PCOS. In: Contemporary endocrinology: androgen excess disorders in women: polycystic ovary syndrome and other disorders. 2nd ed Azziz R, Nestler JE, Dewailly D. eds. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press Inc.; 259–272 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nijland MJ, Ford SP, Nathanielsz PW. 2008. Prenatal origins of adult disease. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 20:132–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Simmons RA. 2007. Developmental origins of diabetes: the role of epigenetic mechanisms. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 14:13–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Manikkam M, Crespi EJ, Doop DD, Herkimer C, Lee JS, Yu S, Brown MB, Foster DL, Padmanabhan V. 2004. Fetal programming: prenatal testosterone excess leads to fetal growth retardation and postnatal catch-up growth in sheep. Endocrinology 145:790–798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Steckler T, Wang J, Bartol FF, Roy SK, Padmanabhan V. 2005. Fetal programming: prenatal testosterone treatment causes intrauterine growth retardation, reduces ovarian reserve and increases ovarian follicular recruitment. Endocrinology 146:3185–3193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wood RI, Foster DL. 1998. Sexual differentiation of reproductive neuroendocrine function in sheep. Rev Reprod 3:130–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Robinson JE, Forsdike RA, Taylor JA. 1999. In utero exposure of female lambs to testosterone reduces the sensitivity of the gonadotropin-releasing hormone neuronal network to inhibition by progesterone. Endocrinology 140:5797–5805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sharma TP, Herkimer C, West C, Ye W, Birch R, Robinson JE, Foster DL, Padmanabhan V. 2002. Fetal programming: prenatal androgen disrupts positive feedback actions of estradiol but does not affect timing of puberty in female sheep. Biol Reprod 66:924–933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sarma HN, Manikkam M, Herkimer C, Dell'Orco J, Welch KB, Foster DL, Padmanabhan V. 2005. Fetal programming: excess prenatal testosterone reduces postnatal luteinizing hormone, but not follicle-stimulating hormone responsiveness, to estradiol negative feedback in the female. Endocrinology 146:4281–4291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Veiga-Lopez A, Astapova OI, Aizenberg EF, Lee JS, Padmanabhan V. 2009. Developmental programming: contribution of prenatal androgen and estrogen to estradiol feedback systems and periovulatory hormonal dynamics in sheep. Biol Reprod 80:718–725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Veiga-Lopez A, Ye W, Phillips DJ, Herkimer C, Knight PG, Padmanabhan V. 2008. Developmental programming: deficits in reproductive hormone dynamics and ovulatory outcomes in prenatal, testosterone-treated sheep. Biol Reprod 78:636–647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. West C, Foster DL, Evans NP, Robinson J, Padmanabhan V. 2001. Intra-follicular activin availability is altered in prenatally-androgenized lambs. Mol Cell Endocrinol 185:51–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Manikkam M, Steckler TL, Welch KB, Inskeep EK, Padmanabhan V. 2006. Fetal programming: prenatal testosterone treatment leads to follicular persistence/luteal defects; partial restoration of ovarian function by cyclic progesterone treatment. Endocrinology 147:1997–2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Steckler T, Manikkam M, Inskeep EK, Padmanabhan V. 2007. Developmental programming: follicular persistence in prenatal testosterone-treated sheep is not programmed by androgenic actions of testosterone. Endocrinology 148:3532–3540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ortega HH, Salvetti NR, Padmanabhan V. 2009. Developmental programming: prenatal androgen excess disrupts ovarian steroid receptor balance. Reproduction 137:865–877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Smith P, Steckler TL, Veiga-Lopez A, Padmanabhan V. 2009. Developmental programming: differential effects of prenatal testosterone and dihydrotestosterone on follicular recruitment, depletion of follicular reserve, and ovarian morphology in sheep. Biol Reprod 80:726–736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Padmanabhan V, Veiga-Lopez A, Abbott DH, Recabarren SE, Herkimer C. 2010. Developmental programming: impact of prenatal testosterone excess and postnatal weight gain on insulin sensitivity index and transfer of traits to offspring of overweight females. Endocrinology 151:595–605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. King AJ, Olivier NB, Mohankumar PS, Lee JS, Padmanabhan V, Fink GD. 2007. Hypertension caused by prenatal testosterone excess in female sheep. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 292:E1837–1841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chang RJ. 2007. The reproductive phenotype in polycystic ovary syndrome. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab 3:688–695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ortega HH, Rey F, Velazquez MM, Padmanabhan V. 2010. Developmental programming: effect of prenatal steroid excess on intraovarian components of insulin signaling pathway and related proteins in sheep. Biol Reprod 82:1065–1075 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Stefani G, Slack FJ. 2008. Small non-coding RNAs in animal development. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 9:219–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ahn HW, Morin RD, Zhao H, Harris RA, Coarfa C, Chen ZJ, Milosavljevic A, Marra MA, Rajkovic A. 2010. MicroRNA transcriptome in the newborn mouse ovaries determined by massive parallel sequencing. Mol Hum Reprod 16:463–471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Choi Y, Qin Y, Berger MF, Ballow DJ, Bulyk ML, Rajkovic A. 2007. Microarray analyses of newborn mouse ovaries lacking Nobox. Biol Reprod 77:312–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fiedler SD, Carletti MZ, Hong X, Christenson LK. 2008. Hormonal regulation of microRNA expression in periovulatory mouse mural granulosa cells. Biol Reprod 79:1030–1037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hossain MM, Ghanem N, Hoelker M, Rings F, Phatsara C, Tholen E, Schellander K, Tesfaye D. 2009. Identification and characterization of miRNAs expressed in the bovine ovary. BMC Genomics 10:443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ro S, Song R, Park C, Zheng H, Sanders KM, Yan W. 2007. Cloning and expression profiling of small RNAs expressed in the mouse ovary. RNA 13:2366–2380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tripurani SK, Lee KB, Wang L, Wee G, Smith GW, Lee YS, Latham KE, Yao J. 2011. A novel functional role for the oocyte-specific transcription factor newborn ovary homeobox (NOBOX) during early embryonic development in cattle. Endocrinology 152:1013–1023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Carletti MZ, Fiedler SD, Christenson LK. 2010. MicroRNA 21 blocks apoptosis in mouse periovulatory granulosa cells. Biol Reprod 83:286–295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hong X, Luense LJ, McGinnis LK, Nothnick WB, Christenson LK. 2008. Dicer1 is essential for female fertility and normal development of the female reproductive system. Endocrinology 149:6207–6212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Jackson LM, Timmer KM, Foster DL. 2008. Sexual differentiation of the external genitalia and the timing of puberty in the presence of an antiandrogen in sheep. Endocrinology 149:4200–4208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Veiga-Lopez A, Steckler TL, Abbott DH, Welch KB, MohanKumar PS, Phillips DJ, Refsal K, Padmanabhan V. 2011. Developmental programming: impact of excess prenatal testosterone on intrauterine fetal endocrine milieu and growth in sheep. Biol Reprod 84:87–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Irizarry RA, Bolstad BM, Collin F, Cope LM, Hobbs B, Speed TP. 2003. Summaries of Affymetrix GeneChip probe level data. Nucleic Acids Res 31:e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Sawyer HR, Smith P, Heath DA, Juengel JL, Wakefield SJ, McNatty KP. 2002. Formation of ovarian follicles during fetal development in sheep. Biol Reprod 66:1134–1150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Quirke LD, Juengel JL, Tisdall DJ, Lun S, Heath DA, McNatty KP. 2001. Ontogeny of steroidogenesis in the fetal sheep gonad. Biol Reprod 65:216–228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Conley AJ, Kaminski MA, Dubowsky SA, Jablonka-Shariff A, Redmer DA, Reynolds LP. 1995. Immunohistochemical localization of 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase and P450 17α-hydroxylase during follicular and luteal development in pigs, sheep, and cows. Biol Reprod 52:1081–1094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hogg K, McNeilly AS, Duncan WC. 2011. Prenatal androgen exposure leads to alterations in gene and protein expression in the ovine fetal ovary. Endocrinology 152:2048–2059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Juengel JL, Heath DA, Quirke LD, McNatty KP. 2006. Oestrogen receptor α and β, androgen receptor and progesterone receptor mRNA and protein localization within the developing ovary and in small growing follicles of sheep. Reproduction 131:81–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mandon-Pépin B, Oustry-Vaiman A, Vigier B, Piumi F, Cribiu E, Cotinot C. 2003. Expression profiles and chromosomal localization of genes controlling meiosis and follicular development in the sheep ovary. Biol Reprod 68:985–995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Saloniemi T, Welsh M, Lamminen T, Saunders P, Mäkelä S, Streng T, Poutanen M. 2009. Human HSD17B1 expression masculinizes transgenic female mice. Mol Cell Endocrinol 301:163–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Miller WL. 2005. Minireview: regulation of steroidogenesis by electron transfer. Endocrinology 146:2544–2550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Padmanabhan V, Sarma HN, Savabieasfahani M, Steckler TL, Veiga-Lopez A. 2010. Developmental reprogramming of reproductive and metabolic dysfunction in sheep: native steroids vs. environmental steroid receptor modulators. Int J Androl 33:394–404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sahakitrungruang T, Tee MK, Blackett PR, Miller WL. 2011. Partial defect in the cholesterol side-chain cleavage enzyme P450scc (CYP11A1) resembling nonclassic congenital lipoid adrenal hyperplasia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 96:792–798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kubota K, Ohsako S, Kurosawa S, Takeda K, Qing W, Sakaue M, Kawakami T, Ishimura R, Tohyama C. 2003. Effects of vinclozolin administration on sperm production and testosterone biosynthetic pathway in adult male rat. J Reprod Dev 49:403–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bernstein E, Kim SY, Carmell MA, Murchison EP, Alcorn H, Li MZ, Mills AA, Elledge SJ, Anderson KV, Hannon GJ. 2003. Dicer is essential for mouse development. Nat Genet 35:215–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Torley KJ, da Silveira JC, Smith P, Anthony RV, Veeramachaneni DN, Winger QA, Bouma GJ. 2011. Expression of miRNAs in ovine fetal gonads: potential role in gonadal differentiation. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 9:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tripurani SK, Xiao C, Salem M, Yao J. 2010. Cloning and analysis of fetal ovary microRNAs in cattle. Anim Reprod Sci 120:16–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Delić D, Grosser C, Dkhil M, Al-Quraishy S, Wunderlich F. 2010. Testosterone-induced upregulation of miRNAs in the female mouse liver. Steroids 75:998–1004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Narayanan R, Jiang J, Gusev Y, Jones A, Kearbey JD, Miller DD, Schmittgen TD, Dalton JT. 2010. MicroRNAs are mediators of androgen action in prostate and muscle. PLoS One 5:e13637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Xu S, Linher-Melville K, Yang BB, Wu D, Li J. 2011. Micro-RNA378 (miR-378) regulates ovarian estradiol production by targeting aromatase. Endocrinology 152:3941–3951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Yao N, Lu CL, Zhao JJ, Xia HF, Sun DG, Shi XQ, Wang C, Li D, Cui Y, Ma X. 2009. A network of miRNAs expressed in the ovary are regulated by FSH. Front Biosci 14:3239–3245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Herrera BM, Lockstone HE, Taylor JM, Wills QF, Kaisaki PJ, Barrett A, Camps C, Fernandez C, Ragoussis J, Gauguier D, McCarthy MI, Lindgren CM. 2009. MicroRNA-125a is over-expressed in insulin target tissues in a spontaneous rat model of type 2 diabetes. BMC Med Genomics 2:54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kong L, Zhu J, Han W, Jiang X, Xu M, Zhao Y, Dong Q, Pang Z, Guan Q, Gao L, Zhao J, Zhao L. 2011. Significance of serum microRNAs in pre-diabetes and newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes: a clinical study. Acta Diabetol 48:61–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. He A, Zhu L, Gupta N, Chang Y, Fang F. 2007. Overexpression of micro ribonucleic acid 29, highly up-regulated in diabetic rats, leads to insulin resistance in 3T3-L1 adipocytes. Mol Endocrinol 21:2785–2794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Pandey AK, Verma G, Vig S, Srivastava S, Srivastava AK, Datta M. 2011. miR-29a levels are elevated in the db/db mice liver and its overexpression leads to attenuation of insulin action on PEPCK gene expression in HepG2 cells. Mol Cell Endocrinol 332:125–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Guo H, Ingolia NT, Weissman JS, Bartel DP. 2010. Mammalian microRNAs predominantly act to decrease target mRNA levels. Nature 466:835–840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kiriakidou M, Tan GS, Lamprinaki S, De Planell-Saguer M, Nelson PT, Mourelatos Z. 2007. An mRNA m7G cap binding-like motif within human Ago2 represses translation. Cell 129:1141–1151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Petersen CP, Bordeleau ME, Pelletier J, Sharp PA. 2006. Short RNAs repress translation after initiation in mammalian cells. Mol Cell 21:533–542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Jakimiuk AJ, Weitsman SR, Magoffin DA. 1999. 5α-reductase activity in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 84:2414–2418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Ferland-McCollough D, Ozanne SE, Siddle K, Willis AE, Bushell M. 2010. The involvement of microRNAs in type 2 diabetes. Biochem Soc Trans 38:1565–1570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.