Abstract

Background

The resectability of colorectal liver metastases is in part largely based on the surgeon's assessment of cross-sectional imaging. This process, while guided by principles, is subjective. The objective of the present study was to assess agreement between hepatic surgeons regarding the resectability of colorectal liver metastases.

Methods

Forty-six hepatic surgeons across Canada were invited. A patient with biologically favourable disease was presented after having received neoadjuvant chemotherapy. The scenario was matched with 10 different scrollable abdominal CT scans representing a maximum response after six cycles of chemotherapy. Surgeons were asked to offer an opinion on resectability of liver metastases, and whether they would use adjunct modalities to hepatic resection.

Results

Twenty-six surgeons participated. Twenty responses were complete. The median number of scenarios deemed resectable was 6/10 (range 3–8). Two control scenarios demonstrated perfect agreement. Agreement on resectability was poor for 4/8 test scenarios, of which one scenario demonstrated complete disagreement. Among resectable cases, the pattern of use of adjunct modalities was variable. A median ratio of 0.87 adjunct modality per resectable scenario per surgeon was used (range 0.25–1.75).

Conclusion

A significant lack of agreement was identified among surgeons on the resectability and use of adjunct modalities in the treatment of colorectal liver metastases.

Keywords: colorectal cancer, consensus, liver metastasis, resectability, multidisciplinary conference, tumour board

Introduction

Colorectal cancer is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer in North America, and the second leading cause of cancer-related death.1 Approximately 50% of patients diagnosed with colorectal cancer will develop liver metastases during the course of their disease.2 For patients with metastatic colorectal cancer isolated in the liver, the cornerstone of therapy is complete surgical resection. The addition of modern chemotherapy to surgery has resulted in 5-year survival rates of 37–58% and 10-year survival rates of 16–30%.3–7

All patients with isolated colorectal liver metastases should be evaluated for liver resection. In the absence of contraindications, the resectability of colorectal liver metastases is in part largely based on the surgeon's assesment of cross-sectional imaging. It is the authors' hypothesis that a significant element of subjectivity influences the determination of resectability. There is currently a paucity of literature addressing the subjectivity of this process, as well as the variability among surgeons. In this context, the objective of the present study was to assess agreement between hepatic surgeons regarding the resectability of colorectal liver metastases. A further aim of the study was to evaluate patterns of use of adjunct modalities to resection among hepatic surgeons.

Materials and methods

After obtaining approval from the Ottawa Hospital Research Ethics Board, hepatic and/or transplant surgeons across Canada were identified through website listings of all university health centres. All hepatic surgeons were invited to participate via email, which included a brief description of the study and its aims. Each surgeon was issued with a unique invitation link. This was done to prevent duplicate answers from the same surgeon. Reminders were sent to surgeons who had not completed the survey.

An email invitation was sent to 46 surgeons. One invitation was not delivered as the email address was not accurate and no alternative email could be identified. Two surgeons replied and stated that they only perform pancreatic surgeries. Forty-three hepatic surgeons were thus considered to have been invited to participate.

The survey consisted of questions pertaining to 10 patients with a standardized clinical scenario. All scenarios were presented with the same clinical history: a young healthy patient with node negative primary colorectal cancer [T3, N0 (0/17)] and a metachronous liver lesion(s) detected at follow-up 4 years after treatment of the primary. The scenarios indicated that the patients were restaged and had no other significant findings. All patients were assumed to have received six cycles of modern neoadjuvant chemotherapy, in order to accommodate for the concept of downstaging.

For each scenario, a scrollable post-treatment computed tomography (CT) scan was presented, representing the extent of disease after six cycles of treatment. Only one phase of a tri-phasic CT scan was shown. This phase represented the best image sequence for a particular patient, and surgeons were informed that no other lesion could be seen on the other CT phases. Only cuts of the liver were shown, as extra-hepatic disease was presumed to be absent.

For 9 out of 10 patients, the post-treatment CT scan was reported to be unchanged from the pre-treatment CT. For the last patient, both pre- and post-treatment CT scans were shown. This patient had a dramatic response with some lesions disappearing with the neoadjuvant chemotherapy treatment.

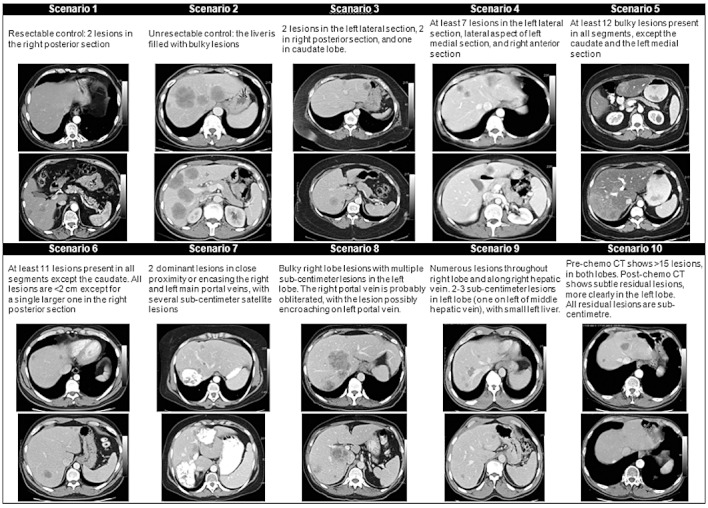

The 10 CT scans represented a variety of clinical presentations of colorectal liver metastases (Fig. 1). Those included single vs. multiple lesions, bilobar disease, lesions in proximity to major vascular structures or ‘ill-located’ lesions, disease where a resection could leave a small future liver remnant, as well as disappearing lesions. Two of the CT scans were included as controls. The first control scan showed a single peripheral lesion, whereas the second represented a liver overburdened with numerous bi-lobar metastases. Those were presumed to be easily recognizable by an expert as resectable and non-resectable disease, respectively. Both control scenarios were embedded within the series of test scenarios and were not labelled as controls.

Figure 1.

Description and selected computed tomography (CT) images of 10 case scenarios presented to survey participants

The surveyed surgeons were asked to decide on the best management for the patient based on the CT scan images. Two options were presented: ‘(i) resection ± adjuncts to resection’, or (ii) ‘this patient is unresectable’. Once the patient was deemed resectable, the surgeons were asked to indicate which adjunct modalities they would plan to use in this case, if any. Available options included radiofrequency ablation (RFA), portal vein embolization (PVE) and a staged hepatectomy. The surgeons could refrain from using these adjunct modalities or could choose one or more option. All surgeons were assumed to have sufficient experience with hepatic surgery and access to modern technologies to be able to render an informed opinion on resectability and the use of adjunct modalities.

At the end of the clinical scenarios, demographical questions were included to further define the participating population of surgeons. Surgeons were asked about their current practices in term of HPB surgery, liver transplant surgery or both. The practice setting was identified in relation to academic (transplant/non-transplant) centres vs. community hospitals. The number of HPB/transplant surgeons, years in practice and the percentage of HPB/transplant surgery in the surgeon's practice were all surveyed. It was also established whether the surgeons were currently involved in the treatment of patients with colorectal liver metastases. Finally participants were asked to provide a short description of their definition of resectability.

A website was created to host the survey. Internet access was required for participation. All survey questions were presented sequentially, and upon completion of a question, the next one was presented. Participants were allowed to go back and change their answers provided that this was done before completion of the survey. An option to save a partially completed survey was also offered, allowing completion at a later time.

All survey data were extracted and analysed using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Richmond, WA, USA). Agreement among surgeons on resectability was presented as proportions of respondents indicating that a given patient had resectable or unresectable disease. Perfect agreement was achieved when all surgeons agreed on resectability or unresectability. Complete disagreement was identified when exactly half of the surgeons chose resectability and half chose unresectability, as would be expected by chance alone. For all cases deemed resectable, the total number of adjunct modalities utilized was calculated per surgeon. In order to account for the different number of scenarios identified as resectable by different surgeons, the total number of adjunct modalities used was standardized against the number resectable scenarios for a given surgeon. These data were thus expressed as a ratio of the number of adjunct modalities used per resectable scenario per surgeon. All continuous variables were presented as medians and range. All dichotomous variables were expressed as proportions or percentages. Medians were compared using Wilcoxon's rank-sum tests.

Results

A total of 26 out of 43 responses were received: 20 of those were complete and 6 responses were partial. All participants were attending surgeons and all but one, practiced at academic institutions. Twelve out of 20 participants were also liver transplant surgeons.

At the time of response, 12 participants had been in practice for at least 5 years. Ten of the participants worked in groups of 3 to 5 surgeons, and HPB surgery represented more than 50% of the workload for 18 participating surgeons. All but one of the participants stated that they were actively involved in the treatment of patients with colorectal liver metastases.

The two control scenarios demonstrated perfect agreement. All 20 surveyed surgeons elected to resect the first control scenario, which represented a single peripherally located metastasis. The second control scenario represented a liver overburdened with multiple, bilateral metastases affecting almost all hepatic segments. None of the participating surgeons offered a liver resection and all 20 agreed on the fact that this disease was unresectable.

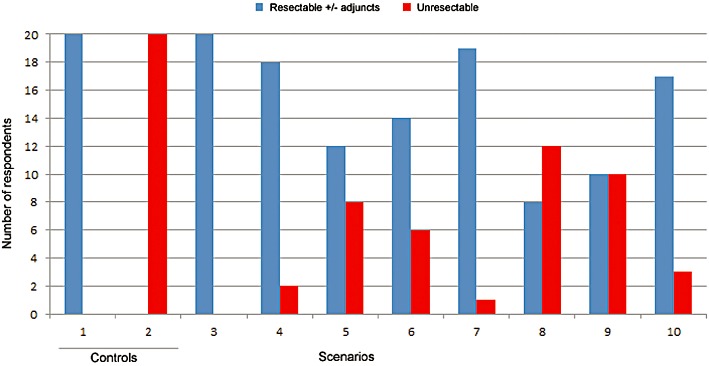

The median number of test scenarios deemed resectable per surgeon was 6 (range 3–8). Agreement on resectability among surgeons was highly variable (Fig. 2). A significant lack of agreement was demonstrated for 4/8 test scenarios (scenarios 5, 6, 8, and 9), with scenario 9 exhibiting complete disagreement. Outside of the control scenarios, only one scenario achieved perfect agreement for resection (scenario 3). The remaining three test scenarios demonstrated good agreement, each with over 17 surgeons concurring on resectability.

Figure 2.

Agreement on resectability per scenario

Surgeons involved in both HPB and transplant surgery were more likely to find patients resectable than surgeons solely practicing HPB surgery [median resectable scenarios 7 (interquartile range 6–7) vs. 5 (4.5–6.5), P = 0.14]. No difference was identified between surgeons with less than 5 years of experience and those with 5 or more [median 6.5 (5–7) vs. 6 (5–7), P = 0.97].

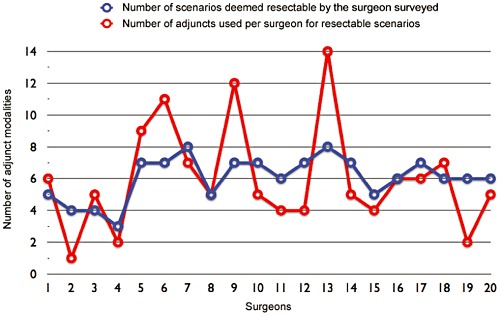

For scenarios considered resectable, the pattern of use of adjunct modalities was variable among participating surgeons (Fig. 3). From the pool of 10 survey scenarios, the median number of adjunct modalities used per surgeon was 5 (range 1–14). The median ratio of adjunct modalities used per resectable scenario per surgeon was 0.87 (range 0.25–1.75). The type of adjunct modalities used was also variable between surgeons (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Comparison of the total number of scenarios resected and adjunct modalities used per surgeon

In defining resectability of colorectal liver metastases, 13 surveyed surgeons provided a definition consistent with a recently published Expert Consensus Statement.8 Other descriptors used included the ability to obtain a 1 cm margin, biological behaviour of the disease, resection based on only pre-chemotherapy imaging and resection of all known ghost lesions if feasible. Two surgeons did not provide a definition, and stated that there is ‘no single definition’.

Discussion

The present study has addressed the resectability of colorectal liver metastases. To the authors' knowledge, this is one of the first studies to specifically describe the variablility associated with this process within a group of hepatic surgeons. The current work is unique in that clinical experts in liver surgery were asked to provide an opinion regarding individual cases based on cross-sectional imaging, assuming ideal oncological parameters. In spite of widely agreed upon modern principles of resectability,8 this study has demonstrated a significant lack of agreement for at least 50% of test scenarios, in addition to tremendous variability in the use of adjunct treatment modalities.

The present study was specifically designed to assess surgeon opinions on technical resectability based on cross-sectional imaging. However, a multitude of other tangible and intangible factors affect whether a patient will undergo curative liver resection, including comorbidities, performance status, tumour biology, response to chemotherapy, the choice of pre-operative staging imaging, presentation at multidisciplinary conferences and local experience with liver surgery. That being said, it can be argued that resectability most frequently boils down to surgical judgement guided by the examination of CT scans and/or magnetic resonance imaging. In order to study this complex process, the present study attempted to control for all other clinical variables that commonly influence such decisions, by proposing a hypothetical healthy patient with favourable disease biology. Although this approach is artificial, the authors argue that it was the most methodologically-sound means to study the given question, without introducing further bias based on additional clinical data.

The criteria for resectability of colorectal liver metastases have evolved over time, and continue to be liberalized.2,8–11 Today, resection principles are based on the remnant liver, with preservation of adequate vascular inflow, outflow and biliary drainage. Current literature advocates that at least two adjacent liver segments should be spared, and the resection should result in macroscopic and microscopic elimination of the disease.12 A sufficient future remnant liver volume is a critical pre-requisite (>20%), with remnant volume requirements increasing in the context of liver injury from chemotherapy, steatosis or hepatitis (30–60%), as well as in the presence of cirrhosis (40–70%). Contraindications to liver resection would include uncontrollable extrahepatic disease such as a non-treatable primary tumour, widespread pulmonary disease, peritoneal disease, extensive nodal disease, such as retroperitoneal or mediastinal nodes and bone or CNS metastases.13 These principles have been formalized in the published recommendations of a 2006 consensus conference.8 Data from the present study would indicate that a majority of practicing hepatic surgeons in Canada are familiar with these principles, as evidenced by definitions provided by survey respondents.

In spite of the above-mentioned principles of resectability, this study has demonstrated that surgeons sometimes arrived at different conclusions based on the same clinical data. Moreover, even in patients deemed resectable, surgeons often opted to use a widely different array of treatment modalities to achieve a presumed similar clinical outcome. These findings highlight the importance of decision-making processes in modern surgical practice.14 Using this premise, it can be inferred that decisions on resectability are influenced by individual surgeon factors such practice patterns, individual biases and experiences, comfort levels with risk, and interpretation of the literature. This interpretation is further supported by the fact that patient-level factors were at least partially controlled for by our use of a standardized clinical scenario.

Pre-operative imaging plays a pivotal role in the evaluation of patients with colorectal liver metastases. It facilitates surgical planning by defining the extent and distribution of hepatic metastases, as well as by identifying extra-hepatic disease.8 Currently, contrast-enhanced CT is the preferred modality in the assessment of colorectal liver metastases. Most comparative studies have shown that MRI is not superior to CT in this context.15,16 As such, the technical aspect of resectability is highly dependent on the interpretation of the cross-sectional imaging, as highlighted in the present study. The onus is on the surgeon to identify and properly select patients who are candidates for liver resection in the presence of colorectal liver metastases. The impact of this process on the patient population is significant, as denial of a liver resection will significantly influence outcomes with important implications for quality of life and overall prognosis.3–7,17–19 In contrast, offering a liver resection when not indicated exposes the patient to significant risk with questionable benefits. As such, the current work would support a definition of resectability that is not based on individual surgeons' opinions, but rather on consensus opinions generated by multidisciplinary conferences or ‘tumour boards’. This belief is supported by literature demonstrating that patients with metastatic colorectal cancer assessed at such conferences are more likely to undergo hepatic metastatectomy.20

The lack of agreement on resectability and the use of adjunct modalities in the pesent study is also highly relevant as it pertains to the concept of conversion therapy. Multiple trials in the literature have reported different conversion rates ranging from 3–72% for patients who were unresectable at presentation but became resectable after chemotherapy.10,21–24 Surprisingly, these variable data were obtained in spite of using similar chemotherapy regimens. However, a closer look reveals the lack of consensus in defining unresectable disease. Some protocols did not include specific criteria for resection of liver metastases, and attempts at a curative resection were left to the surgeon's discretion.21 Others have relied on a single surgeon or a team of physicians to determine resectability.25,26 This observation may partially account for the differences in the reported rates of success of different chemotherapy regimens, such that the effectiveness of downstaging treatments will be heavily impacted by initial definitions of disease resectability.27 The present study lends further support to this hypothesis, particularly given the significant lack of agreement on resectability observed for many test scenarios.

The results of the recent CELIM (Cetuximab and either FOLFOX6 or FOLFIRI in neoadjuvant treatment of unresectable colorectal liver metastases) trial support the conclusions reached in the present study.28 In this trial, patients with colorectal liver metastases initially deemed unresectable by local hepatic surgeons were randomized to cetuximab plus FOLFOX6 or FOLFIRI. After eight cycles of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, study participants were reassessed for resectability by a multidisciplinary expert panel blinded to clinical information. This trial found that 32% of patients initially labelled as unresectable were thought to be potentially resectable by the expert panel. After chemotherapy, the proportion of potentially resectable patients increased to 60%. In total, 34% of enrolled patients eventually underwent R0 liver resection, whereas 46% of patients underwent R0/R1 and/or radiofrequency ablation. The trial authors further highlighted the significant inter-individual variability in opinions on resectability, with 37–58% of patients considered resectable and 20–48% considered unresectable.

Limitations of the present study include the relatively small sample size, the moderate number of test scenarios presented to the surgeons, as well as the requirement for respondents to determine resectability on the basis of a single CT scan phase on a standard definition computer screen. In addition, this work is limited by its descriptive nature, and the homogeneity in the surveyed population of hepatic surgeons, which limits the ability to explain the observed variability of opinions among surgeons.

Conclusion

A significant lack of agreement was identified between surveyed surgeons regarding the resectability of colorectal liver metastases. Similarly, there was poor agreement on the use of adjunct modalities to resection. These findings have important implications concerning definitions of resectability and lend support to resectability of individual patients being determined on the basis of consensus conferences. Patients considered to be unresectable or marginally resectable should be discussed in a multidisciplinary tumour conference before being declined for operation. Tumour boards should follow the best level of medical evidence and consensus guidelines. Further research is required to guide future efforts to standardize the concept of surgical resectability.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Tim Ramsay (Senior Statistician, Ottawa Hospital Research Institute) for helpful comments with the study methodology and manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

Self-funded; no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:277–300. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steele G, Jr, Ravikumar TS. Resection of hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer. Biologic perspective. Ann Surg. 1989;210:127–138. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198908000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fong Y, Fortner J, Sun RL, Brennan MF, Blumgart LH. Clinical score for predicting recurrence after hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer: analysis of 1001 consecutive cases. Ann Surg. 1999;230:309–318. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199909000-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Choti MA, Sitzmann JV, Tiburi MF, Sumetchotimetha W, Rangsin R, Schulick RD, et al. Trends in long-term survival following liver resection for hepatic colorectal metastases. Ann Surg. 2002;235:759–766. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200206000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abdalla EK, Vauthey JN, Ellis LM, Ellis V, Pollock R, Broglio KR, et al. Recurrence and outcomes following hepatic resection, radiofrequency ablation, and combined resection/ablation for colorectal liver metastases. Ann Surg. 2004;239:818–825. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000128305.90650.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vigano L, Ferrero A, Lo Tesoriere R, Capussotti L. Liver surgery for colorectal metastases: results after 10 years of follow-up. Long-term survivors, late recurrences, and prognostic role of morbidity. Ann Surg Oncol. 2008;15:2458–2464. doi: 10.1245/s10434-008-9935-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adam R, Delvart V, Pascal G, Valeanu A, Castaing D, Azoulay D, et al. Rescue surgery for unresectable colorectal liver metastases downstaged by chemotherapy: a model to predict long-term survival. Ann Surg. 2004;240:644–657. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000141198.92114.f6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Charnsangavej C, Clary B, Fong Y, Grothey A, Pawlik TM, Choti MA. Selection of patients for resection of hepatic colorectal metastases: expert consensus statement. Ann Surg Oncol. 2006;13:1261–1268. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9023-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ekberg H, Tranberg KG, Andersson R, Lundstedt C, Hägerstrand I, Ranstam J, et al. Determinants of survival in liver resection for colorectal secondaries. Br J Surg. 1986;73:727–731. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800730917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bismuth H, Adam R, Levi F, Farabos C, Waechter F, Castaing D, et al. Resection of nonresectable liver metastases from colorectal cancer after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Ann Surg. 1996;224:509–520. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199610000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Figueras J, Torras J, Valls C, Llado L, Ramos E, Marti-Raque J, et al. Surgical resection of colorectal liver metastases in patients with expanded indications: a single-center experience with 501 patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:478–488. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0817-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pawlik TM, Choti MA. Surgical therapy for colorectal metastases to the liver. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11:1057–1077. doi: 10.1007/s11605-006-0061-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garden OJ, Rees M, Poston GJ, Mirza D, Saunders M, Ledermann J, et al. Guidelines for resection of colorectal cancer liver metastases. Gut. 2006;55(Suppl 3):iii1–iii8. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.098053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leake PA, Urbach DR. Measuring processes of care in general surgery: assessment of technical and nontechnical skills. Surg Innov. 2010;17:332–339. doi: 10.1177/1553350610379426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bipat S, van Leeuwen MS, Oyen WJ, Planting AS, Ijermans JN, Stoker J. Imaging in the diagnosis of colorectal liver metastases and extrahepatic abnormalities. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 2008;152:857–862. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamel IR, Choti MA, Horton KM, Braga HJ, Birnbaum BA, Fishman EK, et al. Surgically staged focal liver lesions: accuracy and reproducibility of dual-phase helical CT for detection and characterization. Radiology. 2003;227:752–757. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2273011768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scheele J, Stangl R, Altendorf-Hofmann A. Hepatic metastases from colorectal carcinoma: impact of surgical resection on the natural history. Br J Surg. 1990;77:1241–1246. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800771115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rougier P, Milan C, Lazorthes F, Fourtanier G, Partensky C, Baumel H, et al. Prospective study of prognostic factors in patients with unresected hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer. Fondation Francaise de Cancerologie Digestive. Br J Surg. 1995;82:1397–1400. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800821034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pestana C, Reitemeier RJ, Moertel CG, Judd ES, Dockerty MB. The natural history of carcinoma of the colon and rectum. Am J Surg. 1964;108:826–829. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(64)90041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Segelman J, Singnomklao T, Hellborg H, Martling A. Differences in multidisciplinary team assessment and treatment between patients with stage IV colon and rectal cancer. Colorectal Dis. 2009;11:768–774. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2008.01648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Delaunoit T, Alberts SR, Sargent DJ, Green E, Goldberg RM, Krook J, et al. Chemotherapy permits resection of metastatic colorectal cancer: experience from Intergroup N9741. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:425–429. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giacchetti S, Itzhaki M, Gruia G, Adam R, Zidani R, Kunstlinger F, et al. Long-term survival of patients with unresectable colorectal cancer liver metastases following infusional chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin, oxaliplatin and surgery. Ann Oncol. 1999;10:663–669. doi: 10.1023/a:1008347829017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barone C, Nuzzo G, Cassano A, Basso M, Schinzari G, Giuliante D, et al. Final analysis of colorectal cancer patients treated with irinotecan and 5-fluorouracil plus folinic acid neoadjuvant chemotherapy for unresectable liver metastases. Br J Cancer. 2007;97:1035–1039. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clavereo-Fabri MC, Mitry E, Chidiac J, Douillard JY, Meeus P, Raoul JL, et al. Results of surgery for liver metastases (LM) after neoadjuvant chemotherapy (CT) with irinotecan + infusional fluorouracil/leucovorin (Iri-FU/LV) in patients (pts) with colorectal cancer (CRC) Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2003;22:1365a. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alberts SR, Horvath WL, Sternfeld WC, Goldberg RM, Mahoney MR, Dakhil SR, et al. Oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin for patients with unresectable liver-only metastases from colorectal cancer: a North Central Cancer Treatment Group phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:9243–9249. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pozzo C, Basso M, Cassano A, Quirino M, Schinzari G, Triglia N, et al. Neoadjuvant treatment of unresectable liver disease with irinotecan and 5-fluorouracil plus folinic acid in colorectal cancer patients. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:933–939. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Borner MM. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy for unresectable liver metastases of colorectal cancer – too good to be true? Ann Oncol. 1999;10:623–626. doi: 10.1023/a:1008353227103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Folprecht G, Gruenberger T, Bechstein WO, Raab HR, Lordick F, Hartmann JT, et al. Tumour response and secondary resectability of colorectal liver metastases following neoadjuvant chemotherapy with cetuximab: the CELIM randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:38–47. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70330-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]