Abstract

Objectives

Portal hypertension has been reported as a negative prognostic factor and a relative contraindication for liver resection. This study considers a possible role of fibrosis evaluation by transient elastography (FibroScan®) and its correlation with portal hypertension in patients with cirrhosis, and discusses the use of this technique in planning therapeutic options in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Methods

A total of 77 patients with cirrhosis, 42 (54.5%) of whom had HCC, were enrolled in this study during 2009–2011. The group included 46 (59.7%) men. The mean age of the sample was 65.2 years. The principle aetiology of disease was hepatitis C virus (HCV)-related cirrhosis (66.2%). Liver function was assessed according to Child–Pugh classification. In all patients liver stiffness (LS) was measured using FibroScan®. The presence of portal hypertension was indirectly defined as: (i) oesophageal varices detectable on endoscopy; (ii) splenomegaly (increased diameter of the spleen to ≥12 cm), or (iii) a platelet count of <100 000 platelets/mm3.

Results

Median LS in all patients was 27.9 kPa. Portal hypertension was recorded as present in 37 patients (48.1%) and absent in 40 patients (51.9%). Median LS values in HCC patients with and without portal hypertension were 29.1 kPa and 19.6 kPa, respectively (r = 0.26, P < 0.04). Liver stiffness was used to implement the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer algorithm in decisions about treatment.

Conclusions

The evaluation of liver fibrosis by transient elastography may be useful in the follow-up of patients with cirrhosis and a direct correlation with portal hypertension may aid in the evaluation of surgical risk in patients with HCC and in the choice of alternative therapies.

Keywords: portal hypertension, hepatocellular carcinoma, liver fibrosis, transient elastography, liver stiffness, Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer (BCLC)

Introduction

Underlying liver cirrhosis is the strongest predisposing factor for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and is found in 80% of HCC patients.1 However, up to 40% of HCC patients are suitable for consideration for potentially curative interventions. Excluding liver transplantation, which may resolve both conditions, the treatment of HCC and cirrhosis is complex because of the simultaneous needs for radical oncological treatment and the preservation of hepatic parenchyma. In patients with HCC and underlying cirrhosis, the correct estimation of the future hepatic reserve is crucial to ensure patients are correctly selected for surgical resection.2,3 The Barcelona Clinic Liver Classification (BCLC) scheme is considered the most used staging system and therapeutic algorithm for patients with HCC; however, in this classification portal hypertension and increased bilirubin are contraindications for liver resection, but the severity of portal hypertension is only indirectly defined.1 Portal hypertension and hepatic fibrosis are generally considered poor prognostic factors in patients with HCC undergoing liver resection4 and the pathophysiology of liver fibrosis and portal hypertension are directly correlated.5 In fact, the initial event in portal hypertension is increased vascular resistance to portal flow, primarily caused by structural changes such as fibrotic scar tissue and regenerative nodules that compress portal and central venules in which stellate cells are involved in the regulation of the liver microcirculation and portal hypertension.5

Transient elastography (FibroScan®; Echosens SA, Paris, France) is a non-invasive method that uses measurements of liver stiffness (LS) to assess hepatic fibrosis in patients with chronic liver disease. It is easily performed, gives immediate results and has good reproducibility. A mechanical pulse is generated at the skin surface and is propagated through the liver. The velocity of the wave is measured by ultrasound (US). The velocity is directly correlated to the stiffness of the liver, which, in turn, reflects the degree of fibrosis.6 The aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between LS as a surrogate measure of hepatic fibrosis and portal hypertension.4,7,8

Materials and methods

The current study enrolled patients with cirrhosis between November 2009 and August 2011. Patients with portal vein thrombosis were excluded from the study. Data were collected on age, sex, disease aetiology, liver function, presence of portal hypertension, Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) score, alpha-fetoprotein values and tumour characteristics (single or multi-nodular HCC). Cirrhosis diagnoses were based on clinical, laboratory and US findings.9 Liver function was assessed using the Child–Pugh classification. The presence of portal hypertension was indirectly defined according to current guidelines as: (i) oesophageal varices detectable on endoscopy; (ii) splenomegaly (increased diameter of the spleen to ≥12 cm), or (iii) a platelet count of <100 000 platelets/mm3.10 Direct measurements of the hepatic venous pressure gradient (HVPG) were not performed in this series. In all patients, LS was measured using FibroScan® 502 in the right lobe of the liver, through the intercostal space, with the patient lying in the dorsal position and the right arm in maximal abduction. The tip of the transducer probe was covered with coupling gel and placed on the skin between the ribs at the level of the right lobe of the liver.

In patients with HCC, sonographic evaluation was used to assess non-tumour liver parenchyma before FibroScan® LS values were obtained. Ten validated measurements were obtained in each patient. The success rate was calculated as the number of validated measurements divided by the total number of measurements. The results were expressed in kilopascals (kPa). A success rate of ≥60% and an interquartile range (IQR) of ≥20–30% of the median value were considered reliable.6 Liver stiffness was considered as absent or mild for LS values of 0.0–7.0 kPa; LS values of >12.5 kPa were considered indicators of cirrhosis.11 Liver stiffness values of 12.5–17.6 kPa were considered to represent low–moderate LS and values of >17.6 kPa were considered to indicate high LS, in line with Vizzutti et al.12

Possible relationships among LS value, portal hypertension, Child–Pugh class and MELD score were evaluated.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative data are given as the median and IQR. Qualitative data are given in percentages. Differences between the groups (with and without HCC, respectively) were tested using the sign test for quantitative data and chi-squared test (or Fisher's exact test, as appropriate) for qualitative data. The association between LS and portal hypertension was evaluated using the Wilcoxon two-sample test. The association between LS and Child–Pugh class was tested using the Kruskall–Wallis test. Correlations between quantitative variables were computed using Spearman's correlation test. Boxplots were furnished to illustrate median and IQR LS values according to portal hypertension and Child–Pugh class.

Results

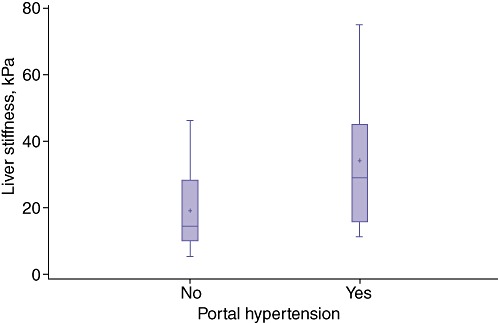

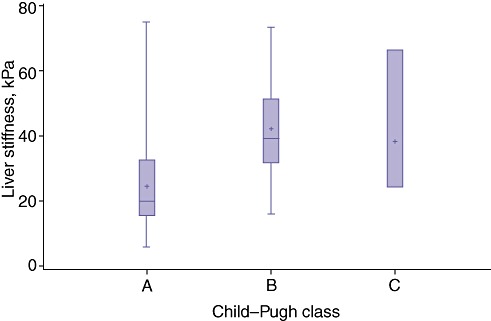

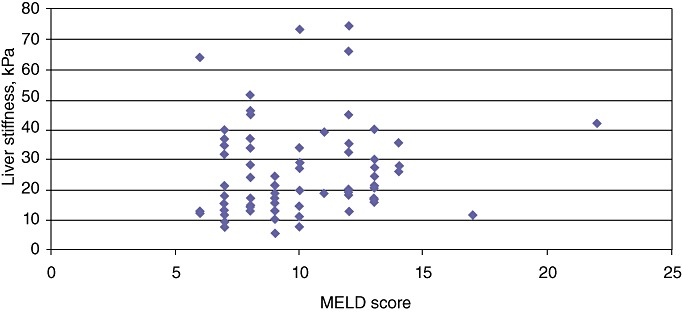

The current study enrolled 77 patients with cirrhosis, 42 (54.5%) of whom had HCC, between November 2009 and August 2011. The mean age of the patient cohort was 65.2 years (range: 45–86 years) and the group included 46 (59.7%) men. Demographics, underlying aetiology, level of hepatic dysfunction and tumour characteristics are shown in Table 1. The presence of portal hypertension according to Child–Pugh class and tumour characteristics in HCC patients is shown in Table 2. Median LS in all patients was 27.9 kPa (IQR 19.8–31.5 kPa), confirming severe fibrosis (F4, Metavir score 4, Ishak score 5–6). Median LS in HCC patients with portal hypertension (29.1 kPa, IQR 19.1–39.3 kPa) was higher than that in patients without portal hypertension (19.6 kPa, IQR 14.9–32.5 kPa) (r = 0.28, P < 0.04) (Fig. 1). A direct correlation between LS and Child–Pugh class was found: patients in Child–Pugh classes B and C presented the highest levels of LS (P < 0.005) (Fig. 2). However, LS measurements correlated with MELD scores: the median LS value in patients with MELD scores of >10 was 29.1 kPa, whereas that in patients with MELD scores of ≤10 was 22.9 kPa (r = 0.26, P = 0.02) (Fig. 3).

Table 1.

General characteristics of patients

| Patients with cirrhosis | P-value | Patients with cirrhosis and HCC | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Patients, n | 35 | 42 | |

| Age, years, median | 60.8 | <0.001 | 69.1 |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 19 (54.3%) | 27 (64.3%) | |

| Female | 16 (45.7%) | 0.37 | 15 (35.7%) |

| Aetiology, n (%) | |||

| Hepatitis C virus | 23 (65.7%) | 28 (66.7%) | |

| Hepatitis B virus | 1 (2.9%) | 8 (19.1%) | |

| Alcohol-related | 3 (8.6%) | – | |

| HBV–HDV co-infections | 1 (2.9%) | 1 (2.4%) | |

| Other aetiology | 7 (19.9%) | 5 (11.9%) | |

| Child–Pugh class, n (%) | |||

| Child–Pugh class A | 30 (85.7%) | 30 (71.4%) | |

| Child–Pugh class B | 3 (8.6%) | 0.23 | 10 (23.8%) |

| Child–Pugh class C | 2 (5.7%) | 2 (4.8%) | |

| Portal hypertension, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 11 (31.4%) | 0.008 | 26 (61.9%) |

| Oesophageal varices, n (%) | 6 (54.5%) | 16 (61.5%) | |

| Grade I | 3 (50.0%) | 10 (62.5%) | |

| Grade II | 2 (33.3%) | 3 (18.8%) | |

| Grade III | 1 (16.7%) | 3 (18.8%) | |

| Spleen diameter ≥12 cm + PC <100 000 platelets/mm3 | 5 (45.5%) | 10 (38.5%) | |

| No | 24 (68.6%) | 16 (38.1%) | |

| MELD score, n (%) | |||

| ≤10 | 30 (85.7%) | 30 (71.4%) | |

| >10 | 5 (14.3%) | 12 (28.6%) | |

| Alpha-fetoprotein, n (%) | |||

| <20 ng/ml | – | 24 (57.1%) | |

| >200 ng/ml | – | 18 (42.9%) | |

| Tumour characteristics, n (%) | |||

| Single | – | 28 (66.7%) | |

| Multinodular | – | 14 (33.3%) | |

HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HDV, hepatitis D virus; MELD, Model for End-stage Liver Disease; PC, platelet count.

Table 2.

Patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) were classified according to tumour characteristics (single or multinodular), Child–Pugh classification and presence of portal hypertension

| Single HCC | Multinodular HCC | |

|---|---|---|

| Patients, n | 28 | 14 |

| Child–Pugh classification, n (%) | ||

| Child–Pugh class A | 20 (71.4%) | 10 (71.4%) |

| With portal hypertension | 14 | 7 |

| Without portal hypertension | 6 | 3 |

| Child–Pugh class B | 6 (21.4%) | 3 (21.4%) |

| With portal hypertension | 6 | 3 |

| Without portal hypertension | – | – |

| Child–Pugh class C | 2 (7.1%) | 1 (7.1%) |

| With portal hypertension | 2 | 1 |

| Without portal hypertension | – | – |

Figure 1.

Median liver stiffness in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma was higher in patients with than without portal hypertension (29.1 kPa vs. 19.6 kPa; P < 0.04)

Figure 2.

A direct correlation between liver stiffness (LS) and Child–Pugh class was found: patients in Child–Pugh classes B and C showed the highest LS values (P < 0.005)

Figure 3.

Liver stiffness (LS) measurements correlated with Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) scores: the median LS value in patients with MELD scores of >10 was 29.07 kPa, whereas the median LS value in patients with MELD scores of ≤10 was 22.91 kPa (P < 0.02)

Treatment decisions were evaluated according to the BCLC algorithm and LS was used to provide a better evaluation of portal hypertension and to predict surgical risk. In this series, of 20 patients with Child–Pugh class A status with a single HCC, eight patients were submitted to liver resection, nine to radiofrequency ablation and three to percutaneous ethanol injection (Table 3). Patients who underwent liver resection presented normal bilirubin values, MELD scores of <10, performance status of 0–1 and Okuda stage I. Four patients displayed no portal hypertension, low–moderate LS and no associated diseases. The other four patients presented with mild or severe portal hypertension, but low–moderate LS. In patients who underwent surgical resection, histological analysis of six specimens demonstrated a direct correlation between FibroScan® data and fibrosis grading. In two specimens the histological grade of cirrhosis did not correlate with FibroScan® data. In these patients, transient elastography underestimated the degree of liver cirrhosis. In the 24 patients with Child–Pugh class B or C status and with multinodular HCC, chemoembolization or systemic therapies were administered. In the surgical group, morbidity occurred in two patients (25.0%), with no mortality. Patients with oesophageal varices at high risk for rupture were treated with endoscopic sclerosis before surgery.

Table 3.

Decision making in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma with Child–Pugh class A status with a single tumour according to the Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer algorithm and liver stiffness values

| Patient | Child–Pugh class | Bilirubin | MELD score | PST | Okuda stage | PHa | Liver stiffness | AD | Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | A | <2.0 | <10 | 0 | I | No | Low–moderate | No | Resection |

| 2 | A | <2.0 | <10 | 0 | I | No | Low–moderate | No | Resection |

| 3 | A | <2.0 | <10 | 0 | I | 2 | Low–moderate | No | Resection |

| 4 | A | <2.0 | <10 | 0 | I | 1 | Low–moderate | Diabetes | Resection |

| 5 | A | <2.0 | <10 | 1 | I | No | Low–moderate | No | Resection |

| 6 | A | <2.0 | <10 | 1 | I | No | Low–moderate | No | Resection |

| 7 | A | 2.2 | <10 | 1 | I | 2 | Low–moderate | No | Resection |

| 8 | A | <2.0 | <10 | 0 | I | 3 | Low–moderate | No | Resection |

| 9 | A | 2.0 | <10 | 0 | I | 1 | High | CVD | PEI |

| 10 | A | 3.0 | <10 | 1 | I | 2 | High | CVD | PEI |

| 11 | A | 3.0 | <10 | 1 | I | 2 | High | Diabetes, CVD | RFA |

| 12 | A | 2.6 | <10 | 0 | I | 1 | High | No | RFA |

| 13 | A | 2.5 | <10 | 1 | I | 3 | High | Diabetes | PEI |

| 14 | A | 2.5 | <10 | 0 | I | 2 | High | No | RFA |

| 15 | A | <2.0 | <10 | 0 | I | 2 | High | No | RFA |

| 16 | A | <2.0 | <10 | 1 | I | 2 | High | Diabetes | RFA |

| 17 | A | <2.0 | <10 | 2 | I | 3 | High | COPD | RFA |

| 18 | A | 2.4 | <10 | 1 | I | 2 | High | CVD | RFA |

| 19 | A | <2.0 | <10 | 2 | I | 2 | High | COPD | RFA |

| 20 | A | 2.3 | <10 | 1 | I | 2 | High | Diabetes | RFA |

1 = oesophageal varices (OV); 2 = OV + splenomegaly (S); 3 = OV + S + platelet count of <100 000 platelets/mm3.

AD, associated diseases; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVD, cardiovascular disease; MELD, Model for End-stage Liver Disease; PEI, percutaneous ethanol injection; RFA, radiofrequency ablation; PH, portal hypertension; PST, performance status test.

Discussion

The pathophysiology of fibrosis and portal hypertension are directly correlated; hepatic stellate cells (HSC) are involved in the regulation of liver microcirculation and portal hypertension.5 In fact, activated HSC have the ability to contract or relax in response to a number of vasoactive substances.5 Activated cells are characterized by loss of vitamin A droplets, increased proliferation, release of proinflammatory, profibrogenic and promitogenic cytokines, migration to sites of injury, increased production of extracellular matrix components, and alterations in the matrix protease activity that provides the fundamental materials for tissue repair.5,13 In acute or self-limiting liver damage, these changes are transient, whereas in persistent injury they lead to chronic inflammation and the accumulation of extracellular matrix, resulting in liver fibrosis and, ultimately, cirrhosis. Several growth factors and cytokines are involved in HSC activation and proliferation, of which transforming growth factor-β and platelet-derived growth factor are probably the most important.13 Preoperative evaluation of the severity of cirrhosis by biopsy of non-tumorous liver for histological grading of fibrosis or measurement of portal pressure (HVPG) has been advocated by some authors, but these methods are less practicable because of the invasiveness of the investigations and are not routinely performed.8,14–17 The serological markers [ialuronic acid, glycopeptides, APRI (aspartate aminotransferase : platelet ratio index) score] are used only in chronic liver disease and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) elastography is still being studied.18 Therefore, at present, transient elastography is considered a valid method to achieve a more accurate diagnosis of fibrosis and, indirectly, of portal hypertension in patients with cirrhosis. However, this method has some limitations: LS measurements can be difficult to obtain in obese patients and in patients with narrow intercostal spaces. Failure rates have ranged from 2.4% to 9.4%.6 The reproducibility of transient elastography is another important prerequisite for its widespread application in clinical practice. In a study by Fraquelli et al., in which 800 transient elastography examinations were performed by two operators in 200 patients with various chronic liver diseases, reproducibility was found to be excellent for both inter- and intraobserver agreement, with intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) of 0.984.19 The validity of LS results also depends on two important parameters: IQR and success rate. However, although a success rate of 60% is recommended, no study has yet achieved this in relation to the use of FibroScan® for the diagnosis of liver fibrosis.6 In some situations, transient elastography can underestimate liver cirrhosis and its accuracy requires to be improved. Vizzutti et al.12 reported a strong relationship between LS and HVPG measurements in 61 patients (r = 0.81, P < 0.0001), with excellent correlations for HVPG values of <10 mmHg (r = 0.81, P < 0.0003) and <12 mmHg (r = 0.91, P < 0.0001), thereby supporting the application of the LS measurement as a non-invasive tool for the identification of chronic liver disease in patients with clinically severe portal hypertension. De Lédinghen and Vergniol6 also reported a direct correlation between LS and the presence of oesophageal varices and the HVPG. Hepatic resection for HCC, mainly through the improved selection of patients, has become a safe procedure, even in patients with cirrhosis, and recent large series have reported good results with significant reductions in postoperative mortality (0.0–4.5%), major morbidity (5.6–19.7%) and liver decompensation.8,15,20,21 In terms of surgery-associated risk, Bruix et al. have reported that patients with cirrhosis and increased portal pressure are at high risk for postoperative hepatic failure and surgical resection should therefore be restricted to patients without portal hypertension.14 The level of hepatic fibrosis is considered a predictor of outcome in patients with HCC.4 Other recent studies have demonstrated that in patients with Child–Pugh class A status, short-term results are similar in patients with and without portal hypertension8 and this value is therefore not an absolute negative predictive risk factor.15 The current study investigated the role of the LS measurement as a potential parameter for the more accurate selection of cirrhosis patients with portal hypertension and HCC. In clinical practice, decisions on the treatment to be administered to cirrhosis patients with HCC are based on many factors, including associated diseases, performance status, aetiology, viral activity, hepatic function (Child–Pugh class and MELD score), and numbers, sizes and sites of HCC lesions. All these parameters are easily obtained with biochemical and radiological tests, as are those related to portal hypertension (platelet count of <100 000 platelets/mm3, splenomegaly, oesophageal varices). However, portal hypertension is very difficult to assess without a direct measurement of HVPG; ‘mild portal hypertension’ was arbitrarily defined by the presence of a single parameter, and ‘severe portal hypertension’ was defined according to the presence of all three parameters. In patients with cirrhosis, it is also difficult to establish the severity of liver fibrosis, which is considered a risk factor directly correlated with portal hypertension. In the current study, the use of transient elastography allowed patients to be divided into those with low–moderate LS (12.5–17.5 kPa) and those with high LS (>17.5 kPa), and established a direct, although not very strong (probably as a result of the small sample size), correlation with portal hypertension values. The LS measurement was used to complement the scoring of risk factors within the BCLC algorithm in order to more accurately select patients for surgery. In 20 patients with Child–Pugh class A status and a single nodule, liver resection was performed in eight patients (40.0%) with low morbidity and no mortality. Although the current results do not demonstrate a strong correlation between portal hypertension and LS, it is the authors' belief that evaluation of fibrosis using a non-invasive method such as FibroScan® elastography may have a possible role in decisions on the treatment of patients with cirrhosis and HCC. This potential role was demonstrated by Kim et al.,22 who reported an LS measurement of 25.6 kPa and an indocyanine green retention rate at 15 min (IGC R15) of 12% as the most accurate cut-off values for the prediction of postoperative hepatic failure.

Conclusions

Liver stiffness measurements may be used to assess both fibrosis and portal hypertension in patients with cirrhosis and HCC, and may lead to the better evaluation of surgical risk in patients with Child–Pugh class A status. The current data require further elaboration in studies on large numbers of patients undergoing liver resection.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Llovet JM, Burroughs A, Bruix J. Hepatocellular carcinoma. Lancet. 2003;362:1907–1917. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14964-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Torzilli G, Donadon M, Marconi M, Palmisano A, Del Fabbro D, Spinelli A, et al. Hepatectomy for stage B and stage C hepatocellular carcinoma in the BCLC classification: results of a prospective analysis. Arch Surg. 2008;143:1082–1090. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.143.11.1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Makuuchi M, Kosuge T, Takayama T, Yamazaki S, Kakazu T, Miyagawa S, et al. Surgery for small liver cancers. Semin Surg Oncol. 1993;9:298–304. doi: 10.1002/ssu.2980090404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vauthey J-N, Dixon E, Abdalla E, Helton WS, Pawlik TM, Taouly B, et al. Pretreatment assessment of hepatocellular carcinoma: expert consensus statement. HPB. 2010;12:289–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2010.00181.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reynaert H, Thompson MG, Thomas T, Geerts A. Hepatic stellate cells: role in microcirculation and pathophysiology of portal hypertension. Gut. 2002;50:571–581. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.4.571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Lédinghen V, Vergniol J. Elastographie impulsionnelle (FibroScan®. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2008;32:58–67. doi: 10.1016/S0399-8320(08)73994-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belghiti J, Kianmanesh R. Surgical treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. HPB. 2005;7:42–49. doi: 10.1080/13651820410024067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Capussotti L, Ferrero A, Viganò L, Muratore A, Polastri R, Bouzari H. Portal hypertension: contraindication to liver surgery? World J Surg. 2006;30:992–999. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-0524-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Obrador BD, Prades MG, Gòmez MV, Domingo JP, Cueto RB, Ruè M, et al. A predictive index for the diagnosis of cirrhosis in hepatitis C based on clinical, laboratory and US findings. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18:57–62. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200601000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bruix J, Sherman M. Management of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2005;42:1208–1236. doi: 10.1002/hep.20933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Castera L, Forns X, Alberti A. Non-invasive evaluation of liver fibrosis using transient elastography. J Hepatol. 2008;48:835–847. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vizzutti F, Arena U, Romanelli RG, Rega L, Foschi M, Colagrande S, et al. Liver stiffness measurement predicts severe portal hypertension in patients with HCV-related cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2007;45:1290–1297. doi: 10.1002/hep.21665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Friedman SL. Molecular regulation of hepatic fibrosis, an integrated cellular response to tissue injury. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:2247–2250. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.4.2247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bruix J, Castells A, Bosch J, Feu F, Fuster J, Garcia-Pagan JC, et al. Surgical resection of hepatocellular carcinoma in cirrhotic patients: prognostic value of preoperative portal pressure. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:1018–1022. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(96)70070-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Imamura H, Seyama Y, Kokudo N, Maema A, Sugawara Y, Sano K, et al. One thousand fifty-six hepatectomies without mortality in 8 years. Arch Surg. 2003;138:1198–1206. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.138.11.1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Poon RT, Fan ST. Hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma: patient selection and postoperative outcome. Liver Transpl. 2004;10 (Suppl.):39–45. doi: 10.1002/lt.20040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farges O, Malassagne R, Flejou JF, Balzan S, Sauvanet A, Belghiti J. Risk of major liver resection in patients underlying chronic liver disease: a reappraisal. Ann Surg. 1999;229:210–215. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199902000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim SU, Ahn SH, Park JY, Kim DY, Chon YC, Choi JS, et al. Can preoperative diffusion-weighted MRI predict postoperative hepatic insufficiency after curative resection of HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma? A pilot study. Magn Reson Imaging. 2010;28:802–811. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2010.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fraquelli M, Rigamonti C, Casazza G, Conte D, Donato MF, Ronchi G, et al. Reproducibility of transient elastography in the evaluation of liver fibrosis in patients with chronic liver disease. Gut. 2007;56:968–973. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.111302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kitisin K, Packiam V, Steel J, Humar A, Gamblin TC, Geller DA, et al. Presentation and outcomes of hepatocellular carcinoma patients at a Western centre. HPB. 2011;13:712–722. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2011.00362.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rahbari NN, Mehrabi A, Mollberg NM, Müller SA, Koch M, Büchler MW, et al. Hepatocellular carcinoma: current management and perspectives for the future. Ann Surg. 2011;253:453–469. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31820d944f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim SU, Ahn SH, Park JY, Kim DY, Chon YC, Choi JS, et al. Prediction of postoperative hepatic insufficiency by liver stiffness measurement (FibroScan®) before curative resection of hepatocellular carcinoma: a pilot study. Hepatol Int. 2008;2:471–477. doi: 10.1007/s12072-008-9091-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]