Abstract

Background

During a pancreatectomy, the left gastric vein (LGV) has an important role in the venous drainage of the stomach (total pancreatectomy, left splenopancreatectomy, pancreatoduodenectomy with venous resection and pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy). Pre-operative knowledge of the LGV's termination is necessary for adequate protection of this vein during dissection. The objective of the present study was to analyse the location of the LGV's termination in a patient population and facilitate its identification in at-risk situations.

Materials and methods

Abdominal computed tomography (CT) images of 86 pancreatic tumour patients (20 of whom underwent surgery), who were treated in our institution between October 2009 and October 2010, were reviewed. Arterial-phase and portal-phase helical CT with three-dimensional reconstruction was performed in all cases. The location of the termination of the LGV was determined and (when the LGV merged with the splenic vein or the splenomesenteric trunk) the distance between the termination and the origin of the portal vein (PV). The correlation between CT imaging data and intra-operative findings was studied.

Results

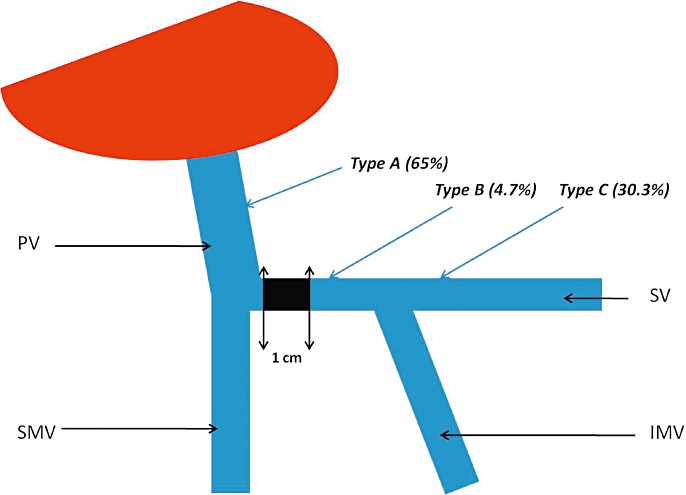

The LGV was identified on all CT images. In 65% of cases (n = 56), the LGV terminated in the PV (upstream of the liver in nine of these cases). The LGV terminated at the splenomesenteric trunk in 4.7% of cases (n = 4) and in the splenic vein in 30.3% of cases (n = 26). When the LGV terminated upstream of the origin of the PV, the distance between the two was always greater than 1 cm. The average distance between the termination of the LGV and the origin of the PV was 14.34 mm (10.2 to 21.1). The anatomical data from CT images agreed with the intra-operative findings in all cases.

Conclusion

Pre-operative analysis of the LGV is useful because the vein can be identified in all cases. Knowledge of the termination's anatomic location enables the subsequent resection to be initiated in a low-risk area.

Keywords: left gastric vein, pancreatectomy, anatomy, 3D CT scan, venous drainage, revascularization

Introduction

The left gastric vein (LGV, formerly referred to as the gastric coronary vein) is a tributary of the portal system. It allows venous blood near the lesser curvature of the stomach to reach the liver through the portal vein (PV). The other venous drainage channels in the stomach are the right gastric vein and the right and left gastroepiploic veins.

In spite of the LGV's importance in the venous drainage of the stomach and its involvement in certain types of surgery (particularly total pancreatectomy, left splenopancreatectomy, pancreatoduodenectomy with venous resection and pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy), only one previous study has investigated this vein's anatomy.1 Indeed, in these situations, the LGV is the only route for venous drainage of the stomach; surgical injury to this vein could cause congestion of the stomach and thus a gastric haemorrhage and would require additional gastrectomy or revascularization procedures.

Computed tomography (CT) analysis of the LGV's path has already been performed as part of the laparoscopic treatment of gastric cancer,2 to locate the vein before surgery and reduce the bleeding that could result from dissection along the common hepatic artery (CHA) during a gastrectomy for cancer.3,4 However, we are not aware of similar studies concerning the pre-operative analysis of the LGV before a pancreatectomy.

In hepatobiliary and pancreatic disease, the LGV can be damaged during the recommended dissection of the CHA's chain of lymph nodes (group 8 in the Japanese Research Society for Gastric Cancer's classification) in cholangiocarcinoma of the liver and the gallbladder,5 pancreatic cancer or a pancreatectomy for a intraductal papillary mucinous tumour (IPMN) withmural nodules.6

Although the LGV usually feeds directly into the PV, anatomic variants with anastomosis at the splenic vein (SV) or splenomesenteric trunk (SMT) have also been reported.7 There are also case reports in which the LGV drains directly into the liver by merging with the end of the left portal branch.8–10

In France, CT of the chest, abdomen and pelvis is part of the local staging of cancerous pancreatic lesions. Three-dimensional portal phase acquisition enables the vessels' anatomy and location in the pancreatic region to be determined. The aim of the present work was to study the main areas of LGV anastomosis in the portal system, with a view to avoiding intra-operative damage in at-risk gastric ischaemia situations such as a total pancreatectomy (with the problem of venous drainage), a pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy (with the problem of post-operative delayed gastric emptying), a pancreatoduodenectomy with venous resection (re-implantation of the splenic vein) and an extended left splenopancreatectomy with sacrifice of the right gastroepiploic vein.

Materials and methods

Patients

The present study is a prospective study of 86 patients referred to Amiens University Medical Center (Amiens, France) between October 2009 and October 2010 for pancreatic tumours. All patients underwent a portal-phase, contrast-enhanced CT scan of the chest, abdomen and pelvis. Twenty out of the 86 patients then underwent surgical resection. The other 66 patients did not have surgical indications (secondary duct IPMN), locally advanced pancreatic tumour (AJCC stage 3 disease), liver metastases or poor overall health status and were not operated on. The surgical resections comprised one total pancreatectomy for diffuse, invasive IPMN, 12 pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomies and seven left splenopancreatectomies (including three with right-side extended resection).

CT-based identification of the LGV

The CT system used was a 16-row LightSpeed VCT scanner (GE Healthcare, Chalfont St Giles, UK). On average, 100 ml of contrast agent was infused at a rate of 2 ml/s. The chest/abdomen/pelvis CT scan was performed 70 s after injection of contrast with a slice thickness of 5 mm. Three-dimensional reconstruction was used to obtain a detailed view of the LGV's termination site. In the 20 resected patients, we studied the correlation between the CT data and the intra-operative findings.

The LGV's termination site was classified as follows: type A, termination on the PV; type B, termination on the SMT (defined as the part of the splenic vein between the union of the inferior mesenteric vein with the splenic vein and the union of the superior mesenteric vein to form the portal vein); and11 type C, termination on the SV (Fig. 1). When the LGV joined the SMT or the SV, the distance between the origin of the PV and the termination of the LGV was calculated.

Figure 1.

Left gastric vein (LGV) termination sites and their frequencies. Type a: termination on the portal vein (PV); Type b: termination on the splenomesenteric trunk (SMT); Type c: termination on the splenic vein (SV); SMV: superior mesenteric vein; IMV: inferior mesenteric vein. The distance between the termination of the LGV (when located on the SMT or the SV) and the origin of the PV was always greater than 10 mm (the zone delimited by the black box)

Results

The LGV was identified in all cases. All three known termination sites were found (Fig. 1).

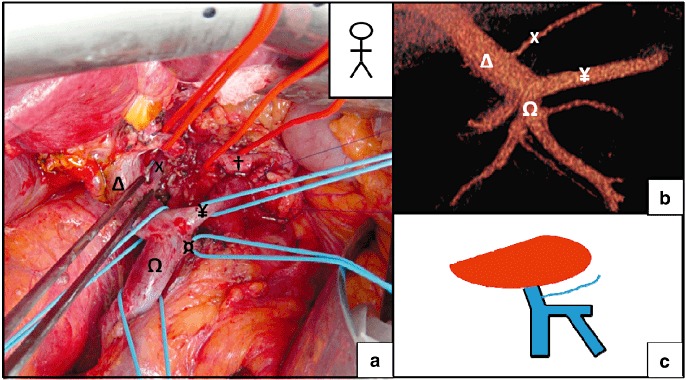

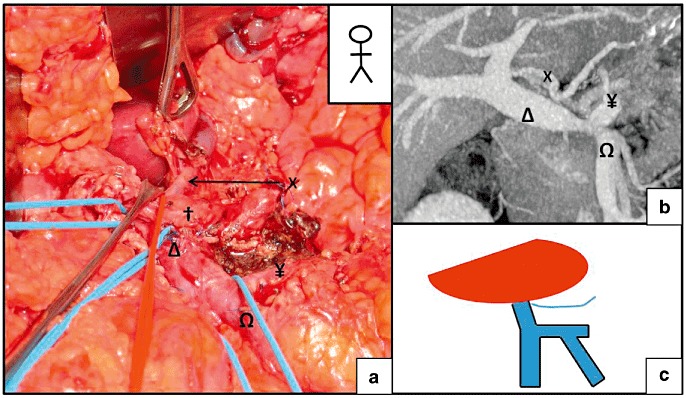

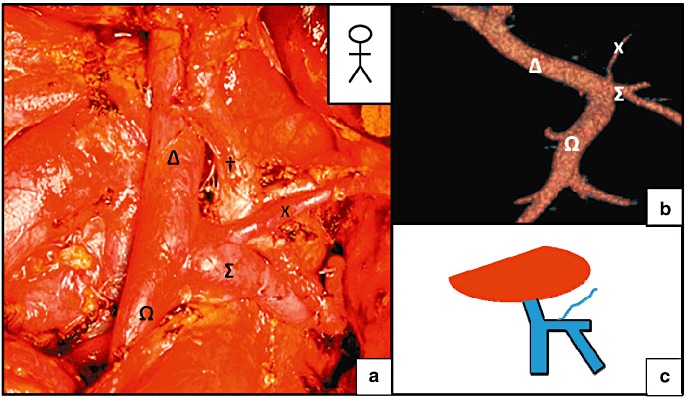

The LGV terminated at the PV in 65% of cases (n = 56) (Fig. 2). In 9 of these 56 patients (10.4% of the overall study population), the LGV terminated within 1 cm of the PV's entry into the liver parenchyma (Fig. 3). Termination on the SMT was observed in 4.7% of the patients (Fig. 4), whereas termination at the SV was found in 26 patients (30.3%) (Fig. 5). When the LGV was inserted into the SV or the SMT (30 cases), the distance between the portal vein and termination of the LGV was 14.3 mm on average but varied greatly from one patient to another (range: 10.2–21.1 mm). However, termination at the SV was never very close to the beginning of the PV; there was always at least 10 mm between the two features (Fig. 6). The LGV did not drain directly into the liver in any of our patients. The CT-derived anatomical data always agreed with the intra-operative findings. The LGV was injured in two of the 20 operated patients (during a standard left pancreatectomy and a standard pancreatoduodenectomy).

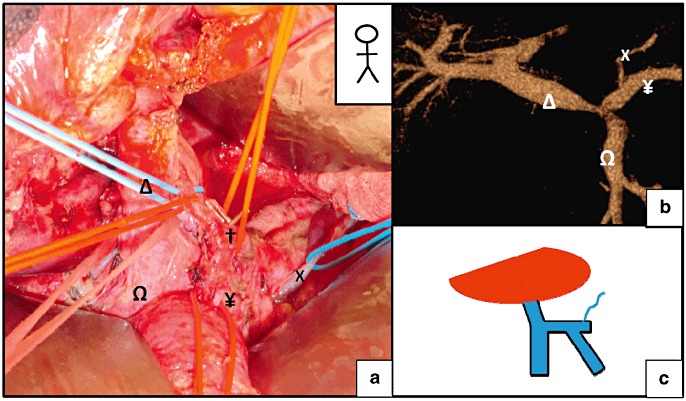

Figure 2.

Termination of the left gastric vein (LGV) on the portal vein (PV). (a) Pancreatoduodenectomy for intraductal papillary mucinous tumour (IPMN). (b) A pre-operative computed tomography (CT) scan revealed the termination of the LGV on the PV. (c) A schematic diagram of the termination of the LGV. X, LGV; †, common hepatic artery; Ω, superior mesenteric vein (SMV); Δ, PV; ¥, splenic vein (SV); ¤, inferior mesenteric vein (IMV)

Figure 3.

Termination of the left gastric vein (LGV) on the portal vein (PV), close to the liver. (a) A pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy. (b) A pre-operative computed tomography (CT) scan revealed the termination of the LGV on the PV less than 10 mm before its entry into the liver. (c) Schematic diagram of the termination of the LGV. X, LGV; †, common hepatic artery; Ω, superior mesenteric vein (SMV); Δ, PV; ¥, splenic vein (SV)

Figure 4.

Termination of the left gastric vein (LGV) on the splenomesenteric trunk (SMT). (a) A total pancreatectomy. (b) A pre-operative computed tomography (CT) scan revealed the termination of the Left gastric vein (LGV) on the SMT more than 10 mm from the origin of the portal vein (PV). (c) Schematic diagram of the termination of the LGV. X, LGV; †, common hepatic artery, Ω, superior mesenteric vein (SMV); Δ: PV, Σ: SMT

Figure 5.

Termination of the Left gastric vein (LGV) on the splenic vein (SV). (a) A pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy. (b) A pre-operative computed tomography (CT) scan revealed the termination of the LGV on the SV. (c) Schematic diagram of the termination of the LGV. X, LGV; †, common hepatic artery; Ω, superior mesenteric vein (SMV); Δ, portal vein (PV); ¥, SV

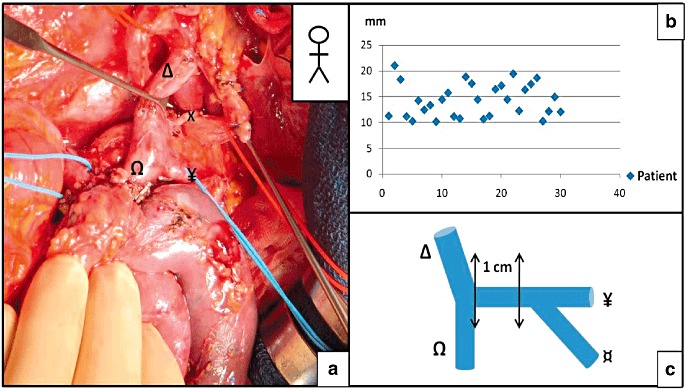

Figure 6.

The left gastric vein–portal vein (LGV–PV) distance when the LGV terminates on the splenic vein (SV) or the splenomesenteric trunk (SMT). (a) A pancreatoduodenectomy. (b) Distribution of the distances between the termination of the LGV and the origin of the PV, when the LGV terminated on the SV or on the SMT. (c) Schematic diagram of the mesenteric-portal confluence, showing the 10-mm zone in which termination of the LGV was never observed. X, LGV; Ω, SMV; Δ, PV; ¥, SV; ¤, inferior mesenteric vein (IMV)

Discussion

This is the first study to have extended the anatomic analysis of the termination of the LGV to a pancreatectomy (a total pancreatectomy, a left splenopancreatectomy, a pancreatoduodenectomy with venous resection and a pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy). We found that the LGV terminated most frequently at the PV, followed by the SV and SMT sites. The termination site was always more than 10 mm from the start of the PV. Furthermore, there was a perfect correlation between the pre-operative CT data and the intra-operative findings.

Total pancreatectomy

During a total pancreatectomy (TP), there are three important operating steps in terms of the venous vascularization of the stomach:12 (i) resection of the gastric antrum (requiring ligation of the right gastroepiploic vein and the right gastric vein), (ii) sectioning of the gastrosplenic ligament (leading to sectioning of the short gastric vessels) and (iii) dissection of the retropancreatic vessels (leading to ligation of the SV upstream of its confluence with the inferior mesenteric vein). Hence, venous drainage of the stomach remnant occurs solely through the LGV. It is therefore very important to protect this vein during the various operating phases, in order to avoid venous stasis and thus gastric ischaemia (found in 9% of TDPs).13 Gastric ischaemia may be responsible for post-operative gastrointestinal bleeding. This complication has been described by Sandroussi,14 who had to re-implant the LGV onto the inferior mesenteric vein.

Pylorus-preserving pancreatoduodenectomy

A pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy seeks to avoid the dumping syndrome found in a non-pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy.15 Nevertheless, this surgery is complicated by delayed gastric emptying and gastric stasis (the frequency of which ranges from 19% to 57%).16 The LGV can be injured during this type of surgery. It has been shown that in a pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy, preservation of the LGV was associated with earlier removal of the nasogastric tube and accelerated recovery of gastric motility.17

Pancreatoduodenectomy with venous resection

When cancer of the head of the pancreas spreads to the vein axis, venous resection yields an R0 resection.18 For extended resection that includes the mesenteric-portal confluence, there are two options: ligation or relocation of the SV. The surgeon's choice depends on where the termination of the LGV is located:

When the LGV feeds into the PV, re-implantation can be avoid because the venous return from the greater curvature of the stomach occurs first through the left gastroepiploic vein and the short gastric vessels near the LGV and then through the portal circulation.

When the LGV feeds into the SV (and when, for some reason, the right gastroepiploic vein cannot be preserved), relocation of the SV is needed to ensure good venous drainage of the stomach.19

Left splenopancreatectomy

A left splenopancreatectomy is mostly indicated for malignant tumours situated in the distal pancreas. There are several variants but the most common techniques20 involve sectioning of the short gastric vessels, displacement of the pancreas, ligation of the SV ahead of its junction with the superior mesenteric vein and then resection of the pancreas at the isthmus. The LGV is small and fragile and can be injured during this type of surgery (Fig. 7). If, during a left splenopancreatectomy, the left vein was to be sacrificed, the right gastric vein should provide sufficient venous drainage of the stomach. The real problem arises in a total pancreatectomy, in which (as in IPNM) the right gastric vein cannot be preserved and venous drainage of the stomach relies on the left gastric vein. The same problem occurs when sectioning the isthmus and then performing centrifugal dissection of the pancreas.21

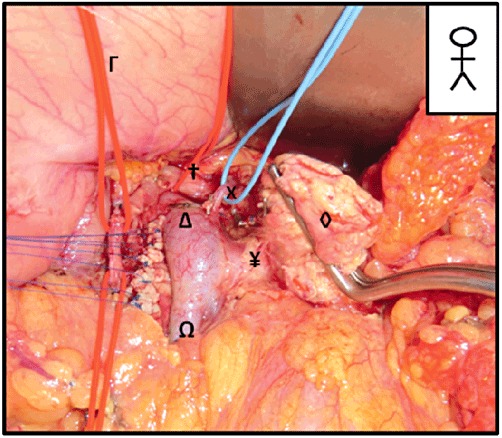

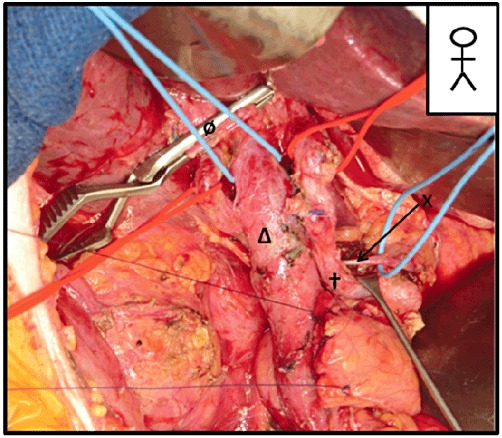

Figure 7.

An extended left splenopancreatectomy. Visualization of the left gastric vein (LGV) on the right side of the portal vein (PV) during an extended left splenopancreatectomy with sacrifice of the right gastroepiploic vein. X, LGV; †, common hepatic artery; Δ, PV; Ω: superior mesenteric vein (SMV); ◊, pancreas; Γ, stomach

How to avoid injuring the LGV during dissection of group 8 lymph nodes

After freeing of the bile duct and ligation of the gastroduodenal artery, direct access to the venous mesenteric-portal trunk is hampered by the CHA (Fig. 8). The CHA is tied back and pulled slightly to the right, in order to provide access to the left edge of the PV (Fig. 9). Two situations occur:

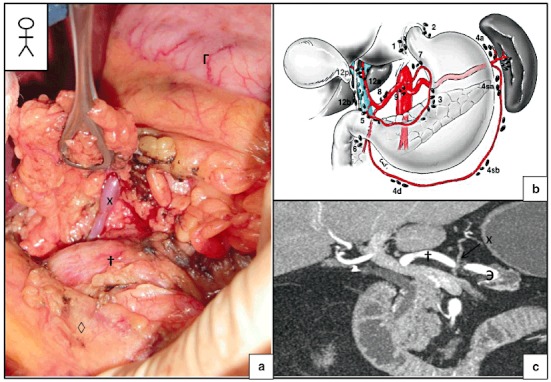

Figure 8.

The area in which damage to the left gastric vein (LGV) can occur. (a) Identification of the LGV during resection of the common hepatic artery's chain of lymph nodes (group 8) during a pancreatoduodenectomy. (b) Schematic diagram representing the various lymph node chains (from 4). (c) Arterial-phase computed tomography (CT) showing the short distance between the common hepatic artery (CHA) and the LGV. X, LGV; †, common hepatic artery; Э, splenic artery; ◊, pancreas; Γ, stomach

Figure 9.

A pancreatoduodenectomy. Skeletization of the common hepatic artery (CHA) during resection of the common hepatic artery's chain of lymph nodes. Visualization of the left gastric vein (LGV) behind the CHA and joining the portal vein (PV) (the usual anatomic form). X, LGV; †, common hepatic artery; Δ, PV; ø, bile duct

The pre-operative CT scan shows that the LGV terminates on the PV. Careful dissection should be performed proximally and distally to the PV, knowing that the LGV will appear on the left side of the PV during the dissection. Once the LGV has been identified, it should be tied back to avoid subsequent damage.

The pre-operative CT scan shows that the LGV terminates on the SV or the SMT. The left side of PV can be dissected without running the risk of damaging the mesenteric-portal confluence. Next, the dissection can continue on towards the SMT, safe in the knowledge that the first centimetre of the SMT does not contain the termination of LGV. Again, once the LGV has been identified, it can be tied back.

Options in the event of LGV injury or tumour involvement

In this specific type of pancreatectomy, the main risk of LGV injury or tumour involvement is gastric congestion caused by the absence of venous drainage. Gastric congestion may lead to gastric. The surgeon has three options:

no action, if there is no congestion of the stomach;

perform a gastrectomy, in addition to the pancreatectomy; and

perform revascularization procedures, such as a bypass of the left colic vein or portal vein using the jugular vein or common iliac vein.

Conclusion

It is important to establish the LGV's anatomy before considering a pancreatectomy because damage to this vein can result in ischaemic gastric complications that will necessitate an additional gastrectomy. A portal-phase, contrast-enhanced abdominal CT scan will enable visualization of the LGV and its anatomic variants in all cases. When the LGV terminates on the SV or the SMT, the dissection must be performed with caution. For a pancreatectomy, the SV should be ligated upstream of its junction with the LGV. In cases of venous resection, care must be taken to ensure that the LGV is connected to the PV axis (by either relocating the SV or directly anatomizing to the PV). When the LGV terminates on the PV, there is little risk of damage during a pancreatectomy.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Bergman RA, Thompson SA, Afifi AK, Saadeh FA. Compendium of Human Anatomic Variations. Baltimore: Urban & Schwarzenberg; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kawasaki K, Kanaji S, Kobayashi I, Fujita T, Kominami H, Ueno K, et al. Multidetector computed tomography for preoperative identification of left gastric vein location in patients with gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2010;13:25–29. doi: 10.1007/s10120-009-0530-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Japanese Gastric Cancer Association. Japanese classification of gastric carcinoma, 2nd English edition. Gastric Cancer. 1998;1:10–24. doi: 10.1007/s101209800016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mutter D, Marescaux J. Gastrectomies pour cancer: principes généraux, anatomie vasculaire, anatomie lymphatique, curages. Encycl Med Chir. 2001;1:40-330-A. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Metairie S, Lucidi V, Castaing D. Le Cholangiocarcinome intra- hépatique. J Chir. 2004;141:315–321. doi: 10.1016/s0021-7697(04)95342-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kobayashi K, Sadakari Y, Ohtsuka T, Takahata S, Nakamura M, Mizumoto K, et al. Factors in intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms of the pancreas predictive of lymph node metastasis. Pancreatology. 2010;10:720–725. doi: 10.1159/000320709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roi DJ. Ultrasound anatomy of the left gastric vein. Clin Radiol. 1993;47:396–398. doi: 10.1016/s0009-9260(05)81059-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohkubo M. Aberrant left gastric vein directly draining into the liver. Clin Anat. 2000;13:134–137. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2353(2000)13:2<134::AID-CA7>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kubik S, Groscurth P. Eine seltene anomalie der extra-hepatischen gallenwege und der V coronaria ventriculi. Chirurg. 1977;48:77–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deneve E, Caty L, Fontaine C, Guillem P. Simultaneous aberrant left and right gastric veins draining directly into the liver. Ann Anat. 2003;185:263–266. doi: 10.1016/S0940-9602(03)80037-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clavien PA, Sarr MG, Fong Y. Atlas of Upper Gastrointestinal and Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Surgery. XXVIII. New York: Springer; 2007. p. 990.p. 62. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jaeck D, Boudjema K, Bachellier P, Weber JC, Asensio T, Wolf P. Duodenopancreatectomie totale. Encycl Med Chir. 1998;1:40-880-E. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jamal W, Sauvanet A, Corcos O, Dokmak S, Couvelard A, Rebours V, et al. Duodénopancréatectomie totale: quelles indications, quelles complications et quelle survie? Résultats d'une série monocentrique de 46 patients. J Chir. 2009;146:9A. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sandroussi C, McGilvray ID. Gastric venous reconstruction after radical pancreatic surgery: case report and review of the literature. J Gastrointest Surg. 2010;14:1027–1030. doi: 10.1007/s11605-010-1192-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Traverso JW, Longmire WP. Preservation of the pylorus in pancreaticoduodenectomy. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1978;146:959–962. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wente MN, Bassi C, Dervenis C, Fingerhut A, Gouma DJ, Izbicki JR, et al. Delayed gastric emptying (DGE) after pancreatic surgery: a suggested definition by the International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) Surgery. 2007;142:761–768. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kurosaki I, Hatakeyama K. Preservation of the left gastric vein in delayed gastric emptying after pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2005;9:846–852. doi: 10.1016/j.gassur.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bachellier P, Nakano H, Oussoultzoglou PD, Weber JC, Boudjema K, Wolf PD, et al. Is pancreaticoduodenectomy with mesentericoportal venous resection safe and worthwhile? Am J Surg. 2001;182:120–129. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(01)00686-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakao A, Takeda S, Inoue S, Nomoto S, Kanazumi N, Sugimoto H, et al. Indications and techniques of extended resection for pancreatic cancer. World J Surg. 2006;30:976–982. doi: 10.1007/s00268-005-0438-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jaeck D, Boudjema K, Bachellier P, Weber JC, Asensio T, Wolf P. Pancreatectomies gauches ou distales. Encycl Med Chir. 1998;1:40-880-D. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goasguen N, Regimbeau JM, Sauvanet A. Distal pancreatectomy with centrifugal dissection of splenic vessels. Ann Chir. 2003;128:57–61. doi: 10.1016/s0003-3944(02)00012-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]