Abstract

Background

The optimal surgical management of patients found to have unresectable pancreatic cancer at open exploration remains unknown.

Methods

Records of patients who underwent non-therapeutic laparotomy for pancreatic cancer during 2000–2009 and were followed until death at Memorial Sloan–Kettering Cancer Center, New York, were reviewed.

Results

Over the 10-year study period, 157 patients underwent non-therapeutic laparotomy. Laparotomy alone was performed in 21% of patients; duodenal bypass, biliary bypass and double bypass were performed in 11%, 30% and 38% of patients, respectively. Complications occurred in 44 (28%) patients. Three (2%) patients died perioperatively. Postoperative interventions were required in 72 (46%) patients following exploration. The median number of inpatient days prior to death was 16 (interquartile range: 8–32 days). Proportions of patients requiring interventions were similar regardless of the procedure performed at the initial operation, as were the total number of inpatient days prior to death. Patients undergoing gastrojejunostomy required fewer postoperative duodenal stents and those undergoing operative biliary drainage required fewer postoperative biliary stents.

Conclusions

In this study, duodenal, biliary and double bypasses in unresectable patients were not associated with fewer invasive procedures following non-therapeutic laparotomy and did not appear to reduce the total number of inpatient hospital days prior to death. Continued effort to identify unresectability prior to operation is justified.

Keywords: periampullary carcinoma, pancreatic cancer, palliative surgery, pancreatic surgery, unresectable pancreatic cancer, therapeutic strategy unresectable

Introduction

Pancreatic cancer remains a lethal malignancy. The majority of patients present with metastatic disease in which survival is measured in months. Resection of pancreatic cancer by pancreaticoduodenectomy is favoured in patients who present with radiographically localized disease as this treatment in combination with systemic therapy provides the only chance for longterm survival.

Despite improvements in preoperative assessment, many patients with pancreatic cancer are unresectable at the time of laparotomy. Non-therapeutic laparotomy has been associated with significant morbidity, a decreased likelihood of receiving systemic treatment, and diminished quality of life.1,2 Several pre-emptive or palliative procedures have been advocated in unresectable patients at the time of non-therapeutic laparotomy. These procedures include biliary bypass and duodenal bypass (gastrojejunostomy) to prevent biliary and duodenal obstruction, respectively, and coeliac plexus block to decrease or prevent pain.

Proponents of prophylactic operative bypass report that 75% of patients with unresectable periampullary malignancy will develop biliary obstruction and 25% will develop gastric outlet obstruction (GOO) prior to death.3,4 However, critics of this strategy have reported that 97% of unresectable patients who do not receive a surgical bypass can be effectively palliated without an operation, particularly now that endoscopic biliary and duodenal stenting have become more effective.5 Thus, the optimal surgical strategy for patients found to be unresectable at the time of exploration remains unclear.

The current study sought to evaluate outcomes in patients with unresectable disease at laparotomy, and to determine the efficacy of biliary, duodenal or double bypass operations. These patients were analysed to determine the number of subsequent invasive procedures they required following exploration and the total number of hospital days they accrued prior to death.

Materials and methods

Under a waiver of authorization from the Memorial Sloan–Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) Institutional Review Board, the MSKCC prospective pancreatic cancer database was retrospectively reviewed to identify all patients who underwent non-therapeutic laparotomy for periampullary carcinoma during 2000–2009. The majority of these patients (93%) underwent laparotomy for pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Only patients who had been followed until death at this institution were included for analysis.

Patients who had undergone non-therapeutic laparotomy were denoted as having had one of four different procedures: exploratory laparotomy; duodenal bypass; biliary bypass, or double bypass. Exploratory laparotomy was defined as an exploration followed by closure without the performance of any surgical bypass procedure(s). Duodenal bypass was defined as a gastrojejunostomy at operation. Biliary bypass was defined as a surgical biliary drainage procedure including hepaticojejunostomy, choledochojejunostomy, hepatico- or choledochoduodenostomy, and cholecystojejunostomy. Double bypass was defined as both a duodenal and a biliary bypass. Postoperative procedures included any surgical, endoscopic, percutaneous or interventional radiology intervention that took place following the initial procedure in order to manage a complication associated with the procedure or to intervene in the context of new obstructive symptoms.

Perioperative events were defined as those occurring within 30 days of laparotomy. Perioperative complications were graded according to an institutional system that has been previously reported.6 Categorical variables were compared using Fisher's exact test. Continuous variables were evaluated using a Student's t-test or analysis of variance (anova) according to the number of comparisons.

Results

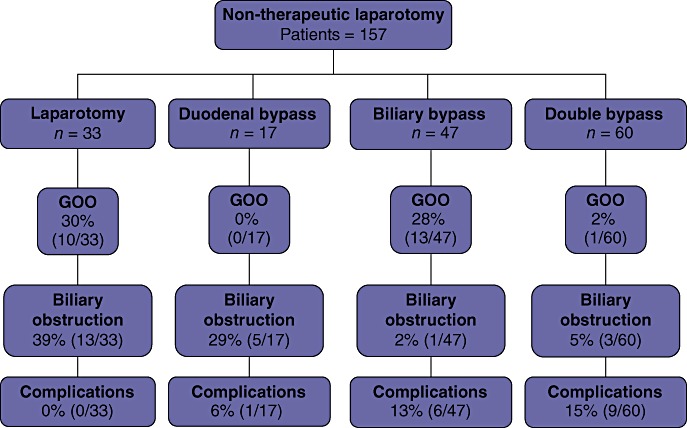

During 2000–2009, 1286 patients were explored for potentially resectable periampullary tumours. All patients underwent exploration with the intent of curative resection. This group included 157 (12%) patients who were designated as unresectable at laparotomy and were followed at the study institution until death. Patient characteristics according to the procedures performed are presented in Table 1. Diagnostic laparoscopy was performed in 109 patients (69%) prior to non-therapeutic laparotomy. Reasons for unresectability were local invasion in 113 (72%) patients, metastatic disease to the liver in 35 (22%) patients, peritoneal disease in six (4%), and both or other causes in three (2%) patients. Having been categorized as unresectable at exploration, 33 (21%) patients underwent no further procedure (laparotomy). Duodenal bypass was performed in 17 (11%) patients; 47 (30%) patients underwent biliary bypass and 60 (38%) underwent double bypass (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Preoperative characteristics in the study cohort

| All patients (n = 157) | Laparotomy patients (n = 33) | Duodenal bypass patients (n = 17) | Biliary bypass patients (n = 47) | Double bypass patients (n = 60) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years, mean | 67 | 69 | 66 | 66 | 65 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 87 (55) | 21 (63) | 5 (29) | 28 (60) | 33 (55) |

| Site of primary (HoP), n (%) | 141 (93) | 31 (97) | 16 (94) | 42 (93) | 52 (91) |

| Preoperative nausea/vomiting, n (%) | 23 (15) | 0 | 9 (53) | 4 (8) | 10 (16) |

| Preoperative bilirubin, mg/dl, mean | 4.5 | 2.1 | 1.0 | 6.4 | 5.4 |

| Prior biliary drainage | 63 (40) | 14 (42) | 6 (35) | 17 (36) | 26 (43) |

| M1 disease at laparotomy, n (%) | 44 (28) | 9 (27) | 5 (29) | 13 (27) | 17 (28) |

HoP, head of the pancreas.

Figure 1.

Procedures and outcomes in 157 patients undergoing non-therapeutic laparotomy for pancreatic cancer. GOO, gastric outlet obstruction

Biliary drainage was performed in 63 patients prior to exploration (via endoluminal catheter or stent in 61 patients and via operative drainage in two patients). Preoperative biliary drainage did not influence intraoperative management of the biliary tree: 43 of the 63 patients (68%) who underwent preoperative drainage also underwent either biliary or double bypass, and 64 of the 94 patients (68%) who did not undergo preoperative drainage underwent operative biliary bypass (Table 1). Elevation of preoperative bilirubin was associated with the performance of biliary bypass as 52 of 56 patients (93%) with bilirubin levels of ≥3 mg/dl underwent either a biliary or a double bypass procedure, whereas only 55 of 100 patients (55%) with bilirubin levels of <3 mg/dl did so (P < 0.001). Patients with preoperative nausea and vomiting were more likely to undergo a gastrojejunostomy (duodenal or double bypass) at surgery than patients without nausea and vomiting [20 of 25 (80%) patients vs. 57 of 132 (43%) patients; P < 0.01] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Patients with postoperative procedures based on preoperative symptoms

| Indication | No nausea/vomiting | Nausea/vomiting | No jaundice | Jaundice | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No GJ (n = 75) | GJa (n = 57) | No GJ (n = 5) | GJa (n = 20) | No BD (n = 39) | BDb (n = 34) | No BD (n = 10) | BDb (n = 73) | |

| Gastric outlet obstruction, n | 23 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 7 | 4 | 3 | 10 |

| Biliary obstruction, n | 14 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 12 | 0 | 6 | 4 |

| Complications, n | 5 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 10 |

Includes patients who had a duodenal bypass and patients who had a double bypass.

Includes patients who had a biliary bypass and patients who had a double bypass.

GJ, gastrojejunostomy; BD, biliary drainage.

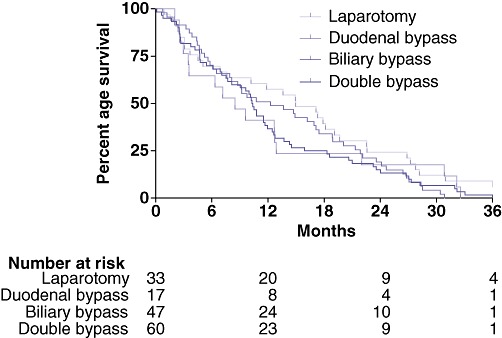

Non-surgical therapy (chemotherapy or radiation therapy) was given to 114 (73%) patients following surgery (Table 3). Median overall survival (OS) in all patients was 11 months [interquartile range (IQR): 5–21 months] (Fig. 2). This did not differ significantly amongst surgical groups.

Table 3.

Postoperative chemotherapy and radiation therapy in the study cohort

| All patients (n = 114) | Laparotomy patients (n = 27) | Duodenal bypass patients (n = 13) | Biliary bypass patients (n = 32) | Double bypass patients (n = 42) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemotherapy, n | 57 | 15 (45) | 8 (47) | 14 (30) | 20 (33) |

| Radiation, n | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 (2) | 0 |

| Chemoradiation, n | 56 | 12 (36) | 5 (29) | 17 (36) | 22 (36) |

Figure 2.

Overall survival in 157 patients undergoing non-therapeutic laparotomy for pancreatic cancer

Following exploration, 72 (46%) patients collectively underwent 212 additional disease-related procedures. For 15 of these patients (15/157, 10%), the postoperative procedure was another operation. Within this group, six patients, representing 8% of patients who did not undergo duodenal bypass at the initial operation, underwent duodenal bypass for GOO. The remaining nine operations were performed to address additional complications of disease other than biliary or duodenal obstruction. Endoscopic procedures (n = 106) were undertaken in 42 (27%) patients following exploration. These included upper endoscopy (n = 33), duodenal stenting (n = 21), endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography with (n = 7) and without (n = 27) stent placement or exchange, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube placement (n = 15), duodenal dilation (n = 1), bronchoscopy (n = 1) and colonoscopy (n = 1). Percutaneous procedures (n = 50) were performed in 30 (19%) patients following exploration. These included biliary drainage procedures (n = 32), drainage of abscess (n = 16) and caval filter placement for deep venous thrombosis (n = 2).

Complications occurred in 44 (28%) patients. Although most complications were minor (Grades I and II), Grade III complications (requiring procedures) were more frequent following biliary and double bypass surgery [15/107 (14%) in biliary and double bypass patients vs. 1/50 (2%) in laparotomy and duodenal bypass patients (P < 0.02)]. Three (2%) perioperative deaths occurred following biliary (n = 1) and double bypass (n = 2) procedures.

There were no differences according to type of initial surgery in the proportions of patients who required postoperative interventions: 55% of non-therapeutic laparotomy patients, 35% of duodenal bypass patients, 51% of biliary bypass patients and 40% of double bypass patients required further intervention (Table 4). Of the 33 patients who underwent laparotomy only at exploration, 18 (55%) required postoperative interventions (36 procedures in total). These included procedures for GOO in 10 patients (30%) and biliary obstruction in 13 (39%) patients. No patient underwent any procedure to address surgical complications. Additional procedures (57 procedures in total) following duodenal bypass were performed in six of 17 (35%) patients. No patient required an additional procedure for GOO. Biliary drainage procedures were performed in five patients and one (6%) patient required a procedure for complications of the original duodenal bypass. Additional procedures (48 procedures in total) were performed in 24 (51%) of the 47 patients who underwent a biliary bypass. A single (2%) patient required an additional procedure for biliary drainage and 13 (28%) patients underwent procedures for GOO. Procedures to address surgical complications associated with the original biliary bypass were required in six (13%) patients. Following double bypass, 24 of 60 (40%) patients underwent additional procedures (n = 71). Biliary or duodenal drainage procedures were required in four patients (one for GOO; three for biliary drainage). Procedures to address surgical complications from the original double bypass were required in nine (15%) patients.

Table 4.

Postoperative characteristics in the study cohort

| All patients (n = 157) | Laparotomy patients (n = 33) | Duodenal bypass patients (n = 17) | Biliary bypass patients (n = 47) | Double bypass patients (n = 60) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All procedures, n (%) | 72 (46) | 18 (55) | 6 (35) | 24 (51) | 24 (40) |

| For biliary drainage, n | 22 | 13 | 5 | 1 | 3 |

| For GOO, n | 24 | 10 | 0 | 13 | 1 |

| Duodenal stents, n | 17 | 9 | 0 | 7 | 1 |

| Total in-hospital days, median | 16 | 16 | 12 | 18 | 16 |

| Complications, n (%) | 44 (28) | 7 (21) | 2 (12) | 11 (23) | 24 (40) |

| Deaths, n | 3 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

GOO, gastric outlet obstruction.

Although there were no differences in the total number of postoperative interventions performed in each group of patients, the indications for these procedures varied according to the procedures performed at exploration (Table 4). Fewer patients needed interventions for GOO following a gastrojejunostomy: 1% of duodenal and double bypass patients, and 29% of laparotomy and biliary bypass patients required such an intervention (P < 0.001). Likewise, fewer patients needed interventions for biliary obstruction after surgical biliary drainage: 4% of biliary and double bypass patients, and 36% of laparotomy and duodenal bypass patients required such an intervention (P < 0.01). Procedures for complications were more common following biliary and double bypass (14% of biliary and double bypass patients, and 2% of laparotomy and duodenal bypass patients required such an intervention), except amongst patients in whom biliary stents had been placed preoperatively [two of 43 (5%) patients who underwent operative biliary drainage after preoperative drainage vs. 13 of 64 (20%) patients who had operative biliary drainage without preoperative drainage (P < 0.02)] (Table 5).

Table 5.

Patient characteristics based on the presence of a preoperative biliary stent

| No preoperative stent (n = 94) | Preoperative stent (n = 61) | |

|---|---|---|

| Patients with preoperative jaundice, n | 51 | 31 |

| Patients with operative biliary drainage, n | 64 | 43 |

| Mean total bilirubin, mg/dl | 5.8 | 2.7 |

| Patients undergoing procedures for postoperative biliary obstruction, n | 12 | 10 |

| Patients undergoing procedures for postoperative complications, n | 13 | 3 |

Following discharge, 91 patients (58%) were readmitted to the hospital. Readmission was required in 54% of patients who had undergone exploratory laparotomy, 82% of patients who had a duodenal bypass, 63% following biliary bypass, and 48% after double bypass. The median number of days spent in hospital prior to death in all patients was 16 (IQR: 8–32 days); this did not differ according to the procedure performed at exploration [laparotomy: 16 days; duodenal bypass: 12 days; biliary bypass: 18 days; double bypass: 16 days (P = not significant)].

Discussion

Improvements in cross-sectional imaging over the past 20 years have enhanced the ability to select patients with pancreatic cancer suitable for resection. Preoperative staging with multidetector computed tomography imaging can determine resectability with sensitivity and specificity that exceed 85%.7 The use of laparoscopy may further identify another 8–17% of patients with subradiologic metastatic disease.8 Thus, current imaging and laparoscopic techniques enable the avoidance of unnecessary laparotomy with greater frequency than in the past. Despite these improvements, however, a subset of patients still undergo laparotomy only to be deemed unresectable when the abdomen is opened. These patients are exposed to the potential morbidity associated with laparotomy without the benefit of resection.

When a non-therapeutic laparotomy has been performed, the surgeon must decide whether or not to perform palliative or pre-emptive bypass procedures. Some reports have suggested that local extension of periampullary malignancies may result in duodenal obstruction in 20–40% of cases.9,10 Biliary obstruction is estimated to occur in 65–75% of patients, with resulting pruritus, diarrhoea, cholangitis and potential hepatic failure.11 Although concomitant prophylactic duodenal and biliary drainage at the time of non-therapeutic laparotomy was standard practice for many years,12 newer, less invasive means of stenting luminal obstructions have augmented the palliative armamentarium.

Both biliary and duodenal stents are associated with excellent technical success rates equivalent to that achieved with operative bypass, and are associated with quicker recovery and shorter length of stay.12–14 This suggests that stents may be preferable to operative bypass in selected patients. In addition, data from MSKCC suggest that 97% of patients with unresectable periampullary cancer can be given successful endoluminal palliation of their symptoms and never require reoperation.5 Despite advances in stent design and improvements in stent patency, recurrent obstructions are more frequent following stent placement, which suggests that stents are not as durable and require more maintenance than operative bypass.15,16 Thus, questions remain for patients found to be unresectable at laparotomy: is it preferable to defer operative bypass and plan to treat future problems endoluminally even if this means that several more procedures may be required? Is it better to operatively prophylax at the time of laparotomy with the hope of maximizing the purpose of the operation with one durable palliative procedure? Is a combination of approaches indicated?

This study was conducted to investigate outcomes in a modern population of patients who had undergone non-therapeutic laparotomy at one institution during 2000–2009. Only patients who had been followed at MSKCC until death were included. This group was chosen because it enabled the capture of all postoperative procedures and comprised 12% of patients brought to the operating room for periampullary tumours during the study time period. The study focused on profiling the frequency of invasive procedures and the total number of hospital days accrued by patients prior to death. These metrics were used as quantitative surrogates for operative palliation.

Roughly half (46%) of all patients in this study required at least one additional invasive procedure prior to death. The proportions of patients requiring additional procedures were similar regardless of the procedure performed at initial exploration (range: 35–54%). No single operative strategy stood out as preventing requirements for additional invasive procedures and the number of in-hospital days did not differ amongst the various procedures. Although no procedure emerged as clearly superior, some advantages unique to each operative strategy were elucidated.

Patients who underwent gastrojejunostomy (duodenal or double bypass) rarely (1%) needed a procedure to treat GOO, whereas 29% of patients who did not undergo gastrojejunostomy (laparotomy or biliary bypass) experienced a GOO that required additional intervention. These data are similar to those published in a study conducted at Johns Hopkins University9 in which 87 patients with unresectable periampullary cancer were randomized to receive hepaticojejunostomy with or without prophylactic gastrojejunostomy. No patients treated with duodenal bypass experienced GOO, but 19% of patients in the no-gastrojejunostomy arm required additional surgery for late GOO.

In the present review, patients with nausea and vomiting who did not undergo gastrojejunostomy did not experience a higher frequency of postoperative GOO (Table 2). However, these patients numbered only five (3% of the whole study cohort) and were probably selected not to have gastrojejunostomy because other signs suggested their symptoms were not secondary to GOO. The presence of nausea and vomiting has been shown by others to be a reliable predictor of impending GOO in patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer,17 and it is highly likely that the omission of gastrojejunostomy in symptomatic patients in the present cohort would have resulted in more endoscopic stenting postoperatively.

In the present study, patients who underwent surgical biliary drainage rarely (3%) required additional interventions for biliary obstruction. In comparison, 36% of patients who did not undergo a biliary bypass required additional procedures (either endoscopic or radiologic) for biliary drainage. The present results following surgical biliary drainage are similar to percentages reported by others. In the largest randomized trial to compare outcomes in operative biliary bypass with those in endoscopic biliary stenting in the management of malignant biliary stricture, Smith et al. reported a 2% incidence of recurrent biliary obstruction in the operative arm.18 Shepherd et al.19 and Artifon et al.20 reported no findings of recurrent obstruction following biliary bypass, but patients in these trials had much shorter survival periods (124 days and 90 days, respectively) than patients in the present study (328 days), which probably reflects the higher percentage of distant disease in the former groups. In the present study, the 36% incidence of postoperative biliary obstruction among patients who did not have operative biliary bypass is lower than the expected 75%, but this may be because approximately 40% of these patients had been treated endoluminally prior to exploration. Patients who underwent biliary bypass were more likely to have elevated bilirubin at the time of exploration and, if this procedure had not been performed, this would almost certainly have required correction postoperatively.

These data demonstrate that patients rarely require interventions for GOO following gastrojejunostomy, and rarely require procedures for malignant biliary obstruction following surgical biliary drainage. It could be inferred that the best procedure to perform at operation would be a double bypass and this is indeed commonly recommended. However, in this review, double bypass patients were found to have undergone just as many postoperative procedures and to have accrued just as many total hospital days as any other group. Although some procedures avoided requirements for treating postoperative GOO and biliary obstruction, this was counterbalanced by requirements for other procedures for other postoperative complications. In addition, double bypass patients experienced operative mortality (2%) that did not occur in the laparotomy and duodenal bypass groups. Interestingly, operative biliary drainage in the presence of a preoperative biliary stent was associated with fewer procedures for postoperative complications. The reason for this is not entirely clear, but it may reflect the fact that a stented biliary tree is more thoroughly drained and therefore yields fewer infectious complications. Findings of improved outcomes when a palliative bypass operation is performed in the setting of a stented biliary tree have been noted by others.17

In the setting of jaundice or symptoms of duodenal obstruction, operative bypass was more likely to be performed and patients who underwent a bypass operation experienced a rate of postoperative re-intervention similar to that in patients who underwent laparotomy alone. Although duodenal bypass and biliary bypass almost completely obviated the need for interventions for additional duodenal or biliary obstruction, the number of procedures they prevented was offset by the procedures performed for other complications that arose. In addition, a small number of bypass patients experienced operative mortality. It is, therefore, reasonable to individualize operative manoeuvres at the time of non-therapeutic laparotomy according to the presence and severity of symptoms. Numerous other patient-specific factors should be considered, including the patient's overall health and ability to tolerate complications, the patient's access to medical care, the cause of the patient's unresectability (local vs. metastatic disease), and the likelihood that the patient will return to surgery for a second attempt at resection. In asymptomatic patients, the surgeon should consider the patient's access to medical care and social support. If these are poor, then a more durable gastrojejunostomy is reasonable. A biliary bypass may be considered in an otherwise healthy patient with limited access to medical care or in whom previous devices have failed. In other contexts, laparotomy is a reasonable option. In the context of impending GOO, gastrojejunostomy is most reasonable. In patients with impending biliary obstruction, if a preoperative stent is in place, a biliary bypass appears reasonable. In patients without a preoperative stent, if the patient is otherwise healthy and can tolerate potential associated complications, a biliary bypass is reasonable.

These data suggest that, at the time of non-therapeutic laparotomy, no operative strategy is clearly superior in terms of the number of postoperative procedures and hospital days that might be accrued. Therefore, an individualized approach using symptoms and other patient-related factors to guide surgical palliation at the time of non-therapeutic laparotomy seems appropriate.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.de Rooij PD, Rogatko A, Brennan MF. Evaluation of palliative surgical procedures in unresectable pancreatic cancer. Br J Surg. 1991;78:1053–1058. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800780909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Watanapa P, Williamson RC. Surgical palliation for pancreatic cancer: developments during the past two decades. Br J Surg. 1992;79:8–20. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800790105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sarr MG, Cameron JL. Surgical palliation of unresectable carcinoma of the pancreas. World J Surg. 1984;8:906–918. doi: 10.1007/BF01656032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Warshaw AL, Swanson RS. Pancreatic cancer in 1988. Possibilities and probabilities. Ann Surg. 1988;208:541–553. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198811000-00001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Espat NJ, Brennan MF, Conlon KC. Patients with laparoscopically staged unresectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma do not require subsequent surgical biliary or gastric bypass. J Am Coll Surg. 1999;188:649–655. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(99)00050-2. discussion 655–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin RC, 2nd, Jaques DP, Brennan MF, Karpeh M. Achieving R0 resection for locally advanced gastric cancer: is it worth the risk of multiorgan resection? J Am Coll Surg. 2002;194:568–577. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(02)01116-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prokesch RW, Chow LC, Beaulieu CF, Nino-Murcia M, Mindelzun RE, Bammer R, et al. Local staging of pancreatic carcinoma with multi-detector row CT: use of curved planar reformations initial experience. Radiology. 2002;225:759–765. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2253010886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.White R, Winston C, Gonen M, D'Angelica M, Jarnagin W, Fong Y, et al. Current utility of staging laparoscopy for pancreatic and peripancreatic neoplasms. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206:445–450. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2007.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lillemoe KD, Cameron JL, Hardacre JM, Sohn TA, Sauter PK, Coleman J, et al. Is prophylactic gastrojejunostomy indicated for unresectable periampullary cancer? A prospective randomized trial. Ann Surg. 1999;230:322–328. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199909000-00005. discussion 328–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Heek NT, de Castro SM, van Eijck CH, van Geenen RC, Hesselink EJ, Breslau PJ, et al. The need for a prophylactic gastrojejunostomy for unresectable periampullary cancer: a prospective randomized multicentre trial with special focus on assessment of quality of life. Ann Surg. 2003;238:894–902. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000098617.21801.95. discussion 902–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.House MG, Choti MA. Palliative therapy for pancreatic/biliary cancer. Surg Clin North Am. 2005;85:359–371. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2005.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garcea G, Ong SL, Dennison AR, Berry DP, Maddern GJ. Palliation of malignant obstructive jaundice. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:1184–1198. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0479-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fiori E, Lamazza A, Volpino P, Burza A, Paparelli C, Cavallaro G, et al. Palliative management of malignant antro-pyloric strictures. Gastroenterostomy vs. endoscopic stenting. A randomized prospective trial. Anticancer Res. 2004;24:269–271. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.George C, Byass OR, Cast JE. Interventional radiology in the management of malignant biliary obstruction. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2010;2:146–150. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v2.i3.146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jeurnink SM, van Eijck CH, Steyerberg EW, Kuipers EJ, Siersema PD. Stent versus gastrojejunostomy for the palliation of gastric outlet obstruction: a systematic review. BMC Gastroenterol. 2007;7:18. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-7-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moss AC, Morris E, Mac Mathuna P. Palliative biliary stents for obstructing pancreatic carcinoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(2):CD004200. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004200.pub4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gray PJ, Jr, Wang J, Pawlik TM, Edil BH, Schulick R, Hruban RH, et al. Factors influencing survival in patients undergoing palliative bypass for pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Surg Oncol. 2012 doi: 10.1002/jso.23047. DOI: 10.1002/jso.23047 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith AC, Dowsett JF, Russell RC, Hatfield AR, Cotton PB. Randomised trial of endoscopic stenting versus surgical bypass in malignant low bile duct obstruction. Lancet. 1994;344:1655–1660. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)90455-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shepherd HA, Royle G, Ross AP, Diba A, Arthur M, Colin-Jones D. Endoscopic biliary endoprosthesis in the palliation of malignant obstruction of the distal common bile duct: a randomized trial. Br J Surg. 1988;75:1166–1168. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800751207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Artifon EL, Sakai P, Cunha JE, Dupont A, Filho FM, Hondo FY, et al. Surgery or endoscopy for palliation of biliary obstruction due to metastatic pancreatic cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2031–2037. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00764.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]