Abstract

The M2 protein from the influenza A virus, an acid-activated proton-selective channel, has been the subject of numerous conductance, structural, and computational studies. However, little is known at the atomic level about the heart of the functional mechanism for this tetrameric protein, a His37-Trp41 cluster. We report the structure of the M2 conductance domain (residues 22 to 62) in a lipid bilayer, which displays the defining features of the native protein that have not been attainable from structures solubilized by detergents. We propose that the tetrameric His37-Trp41 cluster guides protons through the channel by forming and breaking hydrogen bonds between adjacent pairs of histidines and through specific interactions of the histidines with the tryptophan gate. This mechanism explains the main observations on M2 proton conductance.

Proton conductance by the M2 protein (with 97 residues per monomer) in influenza A is essential for viral replication (1). An M2 mutation, Ser31 → Asn, in recent flu seasons and in the recent H1N1 swine flu pandemic renders the viruses resistant to antiviral drugs, amantadine and rimantadine (2). Previous structural determinations of M2 focused primarily on its transmembrane (TM) domain, residues 26 to 46 (3–8). Although the TM domain is capable of conducting protons, residues 47 to 62 following the TM domain are essential for the functional integrity of the channel. Oocyte assays showed that truncations of the post-TM sequence result in reduced conductance (9). Here, we report the structure of the “conductance” domain, consisting of residues 22 to 62, which in liposomes conducts protons at a rate comparable to that of the full-length protein in cell membranes (10, 11) and is amantadine-sensitive (fig. S1). This structure, solved in uniformly aligned 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphatidylcholine:1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine bilayers by solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) at pH 7.5 and 30°C, shows striking differences from the structure of a similar construct (residues 18 to 60) solubilized in detergent micelles (12).

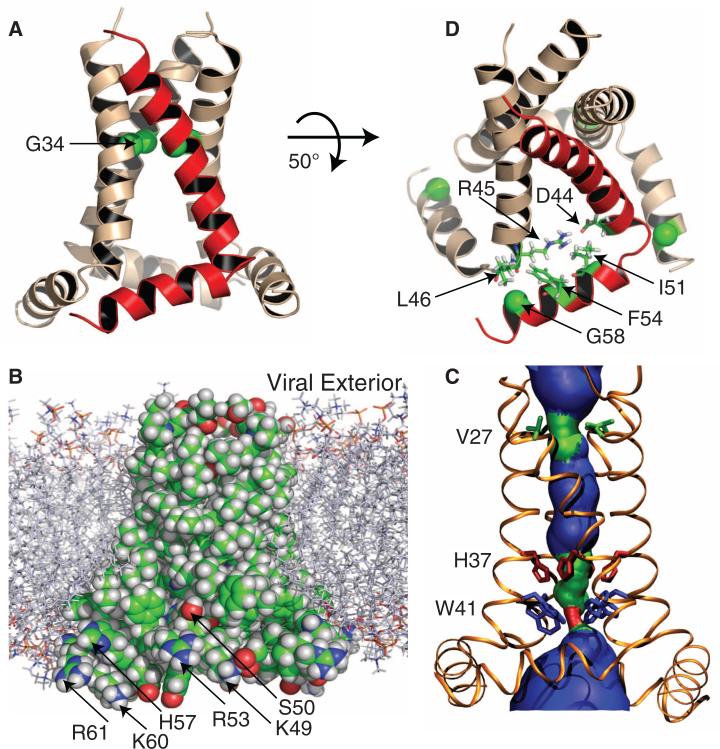

The structure is a tetramer (fig. S2), with each monomer comprising two helices (Fig. 1A). Residues 26 to 46 form a kinked TM helix, with the N-terminal and C-terminal halves having tilt angles of ~32° and ~22° from the bilayer normal, respectively. The kink in the TM helix occurs around Gly34, similar to the kinked TM-domain structure in the presence of amantadine (4). The amphipathic helix (residues 48 to 58) has a tilt angle of 105°, similar to that observed for the full-length protein (13) and resides in the lipid interfacial region (Fig. 1B). The turn between the TM and amphipathic helices is tight and rigid, as indicated by substantial anisotropic spin interactions for Leu46 and Phe47 (their resonances lie close to the TM and amphipathic helical resonance patterns, respectively; see fig. S3). The result is a structural base formed by the four amphipathic helices that stabilizes the tetramer.

Fig. 1.

The tetrameric structure of the M2 conductance domain, solved by solid-state NMR spectroscopy and restrained molecular dynamics simulations, in liquid crystalline lipid bilayers. See (32) for details and fig. S3 for the NMR spectra. (A) Ribbon representation of the TM and amphipathic helices. One monomer is shown in red. The TM helix is kinked around the highly conserved Gly34 (shown as Cα spheres). (B) Space-filling representation of the protein side chains in the lipid bilayer environment used for the NMR spectroscopy, structural refinement, and functional assay. C, O, N, and H atoms are colored green, red, blue, and white, respectively. The nonpolar residues of the TM and amphipathic helices form a continuous surface; the positively charged residues of the amphipathic helix are arrayed on the outer edge of the structure in optimal position to interact with charged lipids. The Ser50 hydroxyl is also shown to be in an optimal position (as Cys50) to accept a palmitoyl group in native membranes. (C) HOLE image (33) illustrating pore constriction at Val27 and Trp41. (D) Several key residues at the junction between the TM and amphipathic helices, including Gly58 (shown as Cα spheres), which facilitates the close approach of adjacent monomers, and Ile51 and Phe54, which fill a pocket previously described as a rimantadine-binding site (12).

The pore formed by the TM-helix bundle is lined by Val27, Ser31, Gly34, His37, Trp41, Asp44, and Arg45, which include all of the polar residues of the TM sequence. The pore is sealed by the TM helices (Fig. 1B) and constricted by Val27 at the N-terminal entrance and by Trp41 at the C-terminal exit (Fig. 1C). The gating role of Trp41 has long been recognized (14), and recently Val27 was proposed to form a secondary gate (15). An important cavity between Val27 and His37 presents an amantadine-binding site (3, 7, 15). This drug-binding site is eliminated in a structure solubilized in detergent micelles (12) because of a much smaller tilt angle of the TM helices (16).

The linewidths of the NMR spectra (fig. S3) are much narrower for the conductance domain than for the TM domain (17), indicating substantially reduced conformational heterogeneity and higher stability (see also fig. S2). In the structure determined here, numerous nonpolar residues of the amphipathic helices extend the hydrophobic interactions interlinking the monomers, with their close approach facilitated by the small Gly58 (Fig. 1D). In particular, Phe48 interacts with Phe55 and Leu59 of an adjacent monomer and Phe54 interacts with Leu46 of another adjacent monomer.

The starting residues of the amphipathic helix, Phe47 and Phe48, are a sequence motif known to signal association of the helix with a lipid bilayer (18). The burial of the hydrophobic portion of the amphipathic helix in the tight intermonomer interface is consistent with hydrogen-deuterium exchange data showing it to be the slowest-exchanging region for the full-length protein in a lipid bilayer (13). Furthermore, the Ser50 hydroxyl here, which in the native protein is a palmitoylated Cys50 residue, is located at an appropriate depth in the bilayer (at the level of the glycerol backbone; see Fig. 1B) for tethering the palmitic acid. A third native-like aspect of the amphipathic helix is the outward projection of the charged residues Lys49, Arg53, His57, Lys60, and Arg61 (Fig. 1B), which conforms to the “positive inside rule” such that M2 interacts favorably with negatively charged lipids in native membranes. The C termini of the amphipathic helices are situated to allow for the subsequent residues of the full-length protein to form the tetrameric M1 binding domain. Contrary to the lipid interfacial location determined here, the detergent-solubilized structure has the four amphipathic helices forming a bundle in the bulk aqueous solution where the amides fully exchange with deuterium (12).

On the external surface at the C terminus of the TM helix, a hydrophobic pocket, with the Asp44 side chain at the bottom, has been described as a binding site for rimantadine (12). In the structure determined here, the large tilt of the TM helices widens the hydrophobic pocket, which is filled by the side chains of Ile51 and Phe54 in the amphipathic helix, preventing accessibility to the Asp44 side chain from the exterior (Fig. 1D). Consequently, the formation of a rimantadine-binding site on the protein exterior is likely an artifact of the detergent environment used for that structural characterization.

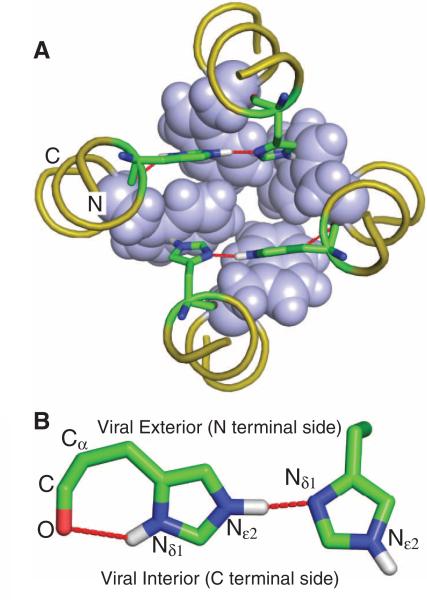

The heart of acid activation and proton conductance in M2 is the tetrameric His37-Trp41 cluster, referred to here as the HxxxW quartet (14, 19, 20). The pKa values for the His37 residues in the TM domain solubilized in a lipid bilayer were determined as 8.2, 8.2, 6.3, and <5.0 (20). At pH 7.5 used here, the histidine tetrad is doubly protonated; each of these two protons is shared between the Nδ1 of one histidine and the Nε2 of an adjacent histidine, giving rise to substantial downfield 15N chemical shifts and resonance broadening for the protonated sites (20) indicative of a strong hydrogen bond (21, 22). The structure of the histidine tetrad as a pair of imidazoleimidazolium dimers is shown in Fig. 2A. In each dimer, the shared proton is collinear with the Nδ1 and Nε2 atoms (Fig. 2B); the two imidazole rings are within the confines of the backbones, to be nearly parallel to each other—a less energetically favorable situation than the perpendicular alignment of the rings in imidazole-imidazolium crystals and in computational studies (23–25). The two Nδ1 and two Nε2 sites of the histidine tetrad not involved in the strong hydrogen bonds are protonated and project toward the C-terminal side (Fig. 2, A and B). The Nε2 protons interact with the indoles of the Trp41 residues (Fig. 2A), and the two Nδ1 protons form hydrogen bonds with their respective histidine backbone carbonyl oxygens (Fig. 2B). Therefore, in this “histidine-locked” state of the HxxxW quartet, none of the imidazole N-H protons can be released to the C-terminal pore, resulting in a completely blocked channel. Furthermore, the only imidazole nitrogens available for additional protonation are the sites involved in the strong hydrogen bonds; acceptance and release of protons from the N-terminal pore by these sites, coupled with 90° side-chain χ2 rotations, would allow the imidazole-imidazolium dimers to exchange partners (fig. S4). That the NMR data show a symmetric average structure suggests that such exchange occurs on a submillisecond time scale.

Fig. 2.

The structure of the HxxxW quartet in the histidine-locked state. (A) Top view of the tetrameric cluster of H37xxxW41 (His37 as sticks and Trp41 as spheres). Note the near-coplanar arrangement of each imidazole-imidazolium dimer that forms a strong hydrogen bond between Nδ1 and Nε2. In each dimer, the remaining Nε2 interacts with the indole of a Trp41 residue through a cation-π interaction. The backbones have four-fold symmetry, as defined by the time-averaged NMR data. (B) Side view of one of the two imidazole-imidazolium dimers. Both the intraresidue Nδ1-H-O hydrogen bond and the interresidue Nε2-H-Nδ1 strong hydrogen bond can be seen. The near-linearity of the interresidue hydrogen bond is obtained at the expense of a strained Cα-Cβ-Cγ angle (enlarged by ~10°) of the residue on the left.

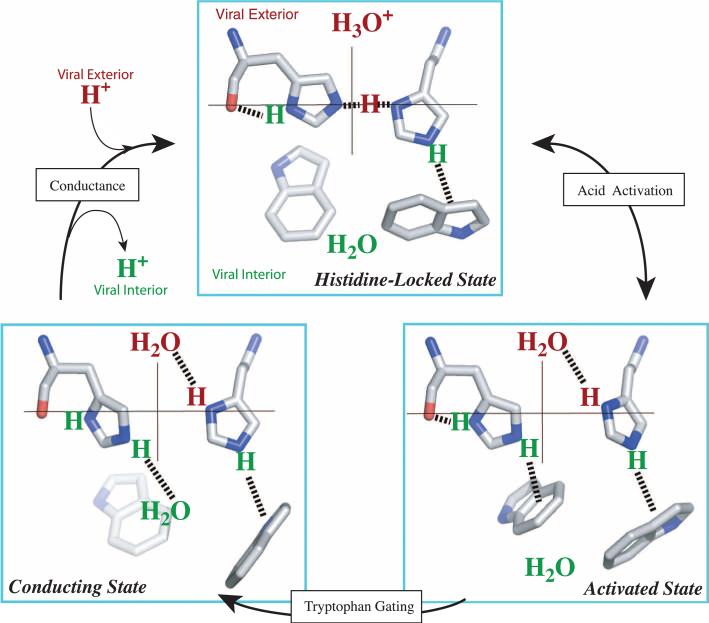

The structure of the HxxxW quartet at neutral pH suggests a detailed mechanism for acid activation and proton conductance (Fig. 3). Under acidic conditions in the viral exterior, a hydronium ion in the N-terminal pore attacks one of the imidazole-imidazolium dimers. In the resulting “activated” state, the triply protonated histidine tetrad is stabilized by a hydrogen bond with water at the newly exposed Nδ1 site on the N-terminal side and an additional cation-π interaction with a Trp41 residue at the Nε2 site on the C-terminal side. Strong cation-π interactions between His37 and Trp41 were observed by Raman spectroscopy in the TM domain under acidic conditions (26). These interactions protect the protons on the C-terminal side from water access. Conformational fluctuations of the helical backbones [in particular, a change in helix kink around Gly34 (27)] and motion of the Trp41 side chain could lead to occasional breaking of this cation-π interaction. In the resulting “conducting” state, the Nε2 proton becomes exposed to water on the C-terminal side, allowing it to be released to the C-terminal pore. Upon proton release, the histidine-locked state is restored, ready for another round of proton up-take from the N-terminal pore and proton release to the C-terminal pore. In each round of proton conductance, the changes among the histidine-locked, activated, and conducting states of the HxxxW quartet can be accomplished by rotations (<45° change in χ2 angle) of the His37 and Trp41 side chains, which are much smaller than those envisioned previously (28) and even less than those needed for the imidazole-imidazolium dimers to exchange partners (fig. S4).

Fig. 3.

Proposed mechanism of acid activation and proton conductance illustrated with half of the HxxxW quartet from a side view. The histidine-locked state (top) is shown with a hydronium ion waiting in the N-terminal pore. Acid activation is initiated with a proton transfer from the hydronium ion into the interresidue hydrogen bond between Nδ1 and Nε2. In the resulting activated state, the two imidazolium rings rotate so that the two nitrogens move toward the center of the pore; in addition, the protonated Nδ1 forms a hydrogen bond with water in the N-terminal pore while the protonated Nε2 moves downward (via relaxing the Cα-Cβ-Cγ angle) to form a cation-π interaction with an indole, thereby blocking water access from the C-terminal pore. The conducting state is obtained when this indole moves aside to expose the Nε2 proton to a water in the C-terminal pore. It was suggested previously (27) that the indole motion involves ring rotation coupled to backbone kinking. Once the Nε2 proton is released to C-terminal water, the HxxxW quartet returns to the histidine-locked state.

This proposed mechanism is consistent with many M2 proton conductance observations. The permeant proton is shuttled through the pore via the histidine tetrad, at one point being shared between Nδ1 and Nε2 of adjacent histidines. No other cations can make use of this mechanism, which explains why M2 is proton-selective. With the permeant proton obligatorily binding to and then unbinding from an internal site (i.e., the histidine tetrad), the proton flux is predicted to saturate at a moderate pH on the N-terminal side (27), which is consistent with conductance observations (29). Such a permeation model also predicts that the transition to saturation occurs at a pH close to the histidine-tetrad pKa for binding or unbinding the permeant proton. Indeed, the transition is observed to occur around pH 6 (29), close to the third pKa of the histidine tetrad. Without the histidines, as in the H37A mutant, the proton flux would lose pH dependence, as observed (19). Another distinguishing feature of the M2 proton channel is its low conductance, at ~100 protons per tetramer per second (fig. S1) (10, 11). Upon acid activation, the HxxxW quartet is primarily in the activated state. Only when the Trp41 gate opens occasionally to form the conducting state is the proton able to be released to the C-terminal pore, thus explaining the low conductance.

In our mechanism, the histidine tetrad senses only acidification of the N-terminal side. This provides an explanation for an observation of Chizhmakov et al. (30) when they applied a positive voltage to drive protons outward in M2-transformed MEL cells. A step increase in the bathing buffer pH from 6 to 8 (with the intra-cellular pH held constant at pH 6) produced a brief increase in outward current, as expected for the added driving force by the pH gradient (31); however, the outward current quickly decayed to a level lower even than that before the pH increase. In our structure, when the pH in the N-terminal side is 8, the HxxxW quartet is stabilized in the histidine-locked state and the Trp41 gate prevents excess protons in the C-terminal pore from activating the histidine tetrad. Upon removal of the Trp41 gate (e.g., by a W41A mutation), a substantial outward current would be produced, as was observed (14). A related observation is that the M2 proton channel can be blocked by Cu2+ (through His37 coordination) applied extracellularly, but not intracellularly (14). Again, the triply protonated histidine tetrad stays predominantly in the activated state, in which the Trp41 gate blocks Cu2+ access to His37 from the C-terminal side. However, the W41A mutation opens that access (14).

The structure of the M2 conductance domain solved in liquid crystalline bilayers has led to a proposed mechanism for acid activation and proton conductance. The mechanism takes advantage of conformational flexibility, both in the backbones and in the side chains, which arises in part from the weak interactions that stabilize membrane proteins. M2 appears to use the unique chemistry of the HxxxW quartet to shepherd protons through the channel.

Acknowledgments

Supported by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grant AI023007. The spectroscopy was conducted at the National High Magnetic Field Laboratory supported by Cooperative Agreement 0654118 between the NSF Division of Materials Research and the State of Florida. T.A.C., H.-X.Z., D.D.B., M.S., and M.Y. have applied for a patent on the mechanism reported here. The structure (an ensemble of eight models) has been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with accession code 2L0J.

Footnotes

Supporting Online Material www.sciencemag.org/cgi/content/full/330/6003/509/DC1 Materials and Methods Figs. S1 to S4 References

References and Notes

- 1.Takeda M, Pekosz A, Shuck K, Pinto LH, Lamb RA. J. Virol. 2002;76:1391. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.3.1391-1399.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gubareva L, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep. 2009;58:1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nishimura K, Kim S, Zhang L, Cross TA. Biochemistry. 2002;41:13170. doi: 10.1021/bi0262799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hu J, et al. Biophys. J. 2007;92:4335. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.090183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stouffer AL, et al. Nature. 2008;451:596. doi: 10.1038/nature06528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cady SD, Hong M. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008;105:1483. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0711500105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cady SD, et al. Nature. 2010;463:689. doi: 10.1038/nature08722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Acharya R, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010;107:15075. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007071107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ma C, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009;106:12283. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mould JA, et al. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:8592. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.12.8592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin TI, Schroeder C. J. Virol. 2001;75:3647. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.8.3647-3656.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schnell JR, Chou JJ. Nature. 2008;451:591. doi: 10.1038/nature06531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tian C, Gao PF, Pinto LH, Lamb RA, Cross TA. Protein Sci. 2003;12:2597. doi: 10.1110/ps.03168503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tang Y, Zaitseva F, Lamb RA, Pinto LH. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:39880. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M206582200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yi M, Cross TA, Zhou HX. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2008;112:7977. doi: 10.1021/jp800171m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cross TA, Sharma M, Yi M, Zhou HX. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.07.005. 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li C, Qin H, Gao FP, Cross TA. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2007;1768:3162. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.08.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lau TL, Dua V, Ulmer TS. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:16162. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801748200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Venkataraman P, Lamb RA, Pinto LH. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:21463. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412406200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hu J, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2006;103:6865. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song X.-j., McDermott AE. Magn. Reson. Chem. 2001;39:S37. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Song X.-j., Rienstra CM, McDermott AE. Magn. Reson. Chem. 2001;39:S30. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quick A, Williams DJ. Can. J. Chem. 1976;54:2465. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krause JA, Baures PW, Eggleston DS. Acta Crystallogr. B. 1991;47:506. doi: 10.1107/s0108768191000915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tatara W, Wojcik MJ, Lindgren J, Probst M. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2003;107:7827. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okada A, Miura T, Takeuchi H. Biochemistry. 2001;40:6053. doi: 10.1021/bi0028441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yi M, Cross TA, Zhou HX. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009;106:13311. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906553106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pinto LH, et al. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1997;94:11301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chizhmakov IV, et al. J. Physiol. 1996;494:329. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chizhmakov IV, et al. J. Physiol. 2003;546:427. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.028910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.The brief increase can be attributed to the release of protons from the triply protonated histidine tetrad to the N-terminal pore (as illustrated by the back arrow from the activated state to the histidine-locked state in Fig. 3) when the pH there is suddenly increased from 6 to 8. With these protons released, the histidine tetrad then becomes doubly protonated and the tryptophan gate becomes closed.

- 32.See supporting material on Science Online.

- 33.Smart OS, Neduvelil JG, Wang X, Wallace BA, Sansom MS. J. Mol. Graph. 1996;14:354. doi: 10.1016/s0263-7855(97)00009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]