Abstract

Purpose

The purpose of this review was to assess effectiveness of nonsurgical treatment on irritable behavior of infants with Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD).

Design and Method

A systematic literature review was conducted.

Results

Research targeted treatment for irritability in infants with GERD. All interventions including placebo were similar in reducing irritability. Which specific intervention is best for which infant is not yet known. Minor adverse effects that could increase discomfort in infants were found with pharmacologic treatments.

Practice Implications

Knowledge of the effects of treatment on irritability and regurgitation can assist the nurse to work with other care providers in deciding how best to treat an individual infant.

Search terms: GERD, infant, irritability, nursing, review, treatment

The lower esophageal sphincter (LES) serves as a barrier between the stomach and esophagus. During normal transient relaxation of the LES, gastric contents flow back into the esophagus. Gastroesophageal reflux (GER), the passage of gastric contents back into the esophagus, is a normal human function that occurs most frequently after meals. GER is especially common in infants due to: a short esophagus, the immaturity of the esophagus and stomach, an obtuse angle of His, and a diet consisting primarily of liquids (Colin & Hassall, 2008; Vandenplas, Salvatore, & Hauser, 2005). Regurgitation of refluxed material occurs in 67% of infants by age 4 months and decreases to 0–5% by 12 months of age (Martin et al. 2002; Nelson, Chen, Syniar, & Christoffel, 1997). A more problematic condition than GER is Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD). GERD is present in infants “when reflux of gastric contents is the cause of troublesome symptoms” (i.e., when the symptoms “have an adverse effect on the well-being of the pediatric patient”; Sherman et al., 2009, pp. 1280, 1281). Examples of troublesome symptoms include discomfort when spitting up, irritability, and/or back arching. The frequency of clinically significant reflux peaks in 23% of infants at 6 months of age and decreases to 14% at 7 months of age (Nelson et al., 1997). The purpose of this review is to assess the effect of nonsurgical treatments on the irritable behavior often associated with symptoms of GERD in infants.

Irritability and Other Symptoms of GERD

Parents describe various signs associated with reflux in their infants including: irritability, distress with spitting up, and frequent back arching. These signs may, however, be associated with other discomfort experienced by the infant (e.g., pain, gaseousness) not specific to GERD (Sherman et al., 2009). Additionally, reflux alone is not considered sensitive or specific for the diagnosis of GERD, but the combination of reflux and irritability has been shown to increase the specificity of a GERD diagnosis in infants when validating the presence of GERD using pH monitoring (Heine, Jordan, Lubitz, Meehan, & Catto-Smith, 2006). Infants with reflux may be more irritable than other infants (Vandenplas, Badriul, Verghote, Hauser, & Kaufman, 2004). In a study of 185 infants referred for reflux, 70% were reported by their mothers to be irritable (Kleinman et al., 2006).

Irritability is troublesome for mothers and affects their relationships with their infants. Mothers of infants with GERD have reported that their infants were more demanding and recounted more feelings of anger and frustration than other mothers (Mathisen, Worrall, Masel, Wall, & Shepherd, 1999). Infant irritability is associated with maternal fatigue, anxiety, depression, and feelings of low self-efficacy and learned helplessness that negatively affect the mother-infant relationship (St James-Roberts, 2008). Mothers who reported problems with infant feeding and crying during the early months of age also perceived their children as more vulnerable and more behaviorally problematic than other mothers (Mathison et al., 1999). And finally, some studies suggest that persistent infant crying and fussing is associated with an increased risk of child abuse (Talvik, Alexander, & Talvik, 2008). Because irritability is a troublesome (and frequently persistent) symptom that adversely impacts both the mother (or caregiver) and infant, it needs to be considered in determination of treatment effectiveness.

Treatment for Infants with Symptoms of GERD

Typical pharmacologic intervention for infants with GERD is acid suppressant medication for at least 8 weeks (Diaz et al., 2007). The most frequently used medications are Histamine H2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs) or Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs). H2RAs reduce histamine-induced gastric acid and secretion (Tighe, Afzal, Bevan, & Beattie, 2009). PPIs are considered more “potent” than H2RAs, since they increase the pH of gastric contents, facilitate gastric emptying, and reduce the volume of reflux (Wallace & Sharkey, 2011). Between 1999 and 2004, a greater than 7-fold increase in the prescription of PPIs for infants occurred (Barron, Tan, Spalding, Bakst, & Singer, 2007).

Typical nonpharmacologic treatments include smaller volumes of formula with more frequent feedings, thickened formula, and positioning (Carroll, Garrison, and Christakis, 2002; Craig, Hanlon-Dearman, Sinclair, Taback, & Moffatt, 2004; Horvath, Dziechciarz, and Szajewska, 2008). Therapies used for infant irritability, irrespective of GERD status, also may help infants with GERD. Infants who are distressed by reflux may benefit from therapy that promotes relaxation and sleep, such as massage (Underdown, Barlow, Chung, & Stewart-Brown, 2006).

Reasons for an Updated Review

With the exception of a recent review by Higginbotham (2010) who reported on the effectiveness of PPIs on general symptoms of GERD, the efficacy of anti-reflux medications typically is not distinguished between infants less than 1 year of age and older age groups. Reviews of nonpharmacologic treatments focus primarily on their effectiveness in reducing reflux (Carroll et al., 2002; Craig et al., 2004; Horvath et al., 2008). This review differs from other reviews by combining available research on pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatment that includes the effect of treatments on infant irritability in GERD, primarily in healthy infants less than 1 year of age. This review also incorporates research that has examined general treatment for infant irritability and research of complementary or alternative therapies for infant irritability. The questions of interest are, in infants with symptoms of GERD who are less than 12 months of age, (a) What are the benefits of pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatments on irritability for infants with symptoms of GERD? and (b) What is the efficacy and safety of pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatments for reflux and acid reflux?

Methods

Criteria for Considering Studies for this Review

Types of studies

The focus of this review is primarily on infant irritability in GERD. Because of consistently improving guidelines of research methodology and reporting such as CONSORT (Schulz, Altman, Moher, & CONSORT Group, 2010) and Cochrane Guidelines (Higgins & Green, 2008), only reports from 2002–2011 were included in this review. Only full-text articles and articles written in English were used. Because H2RAs and PPIs are the primary pharmacologic agents utilized in infants to treat GERD (Diaz et al., 2007), only pharmacologic studies examining these drugs were included. Nonpharmacologic studies addressing thickened feedings, positioning, and other measures such as adjustments in time and frequency of feeding were included. Few studies were anticipated that addressed treatment of irritability associated with GERD. Therefore, crossover, quasi-experimental, correlational, and single-group pre-post test designs were included in addition to randomized controlled trials (RCTs). These same designs were sought for studies targeting infant irritability not associated with GERD.

Types of participants

Inclusion criteria included studies that focused on healthy infants less than 12 months of age, who were born at term and had symptoms of GERD or a diagnosis of GERD. While the goal was to include studies that focused only on full-term infants, protocols utilizing pharmacologic treatment often included infants born as young as 32 weeks gestational age. In order to capture the results from these important studies, those that combined preterm and term infants were included. Where these studies were cited, the combination of gestational ages (preterm and term) is noted in this report. Other criteria were that the entire sample had no other illness that might cause or aggravate GERD or irritability. For studies addressing only irritability, inclusion criteria consisted of infants who were healthy, born at term, were less than 12 months of age, and displayed irritability more than what would be considered typical for a young infant.

Types of Outcome Measures

Primary outcome

The primary outcome of this review is discussion of treatments that addressed irritability (crying and fussiness) in infants with symptoms of GERD.

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcomes are treatments that addressed (a) amount and frequency of reflux, (b) relief of acid reflux, and (c) safety of the treatment.

Search Methods for Identification of Studies

Data collection and analysis

Databases searched were Pubmed from the National Library of Medicine, CINAHL, Med Consult, and Nursing Consult. Limits of English language, Humans, and age 0 through 23 months (the age for infants allowed on databases), were placed on all searches. Gastroesophageal reflux was combined by AND with each of the following: treatment, anti-reflux medication, histamine H2 antagonists, proton pump inhibitors, conservative treatment, nonpharmacologic treatment, alternative treatment, complementary treatment, irritability, and feeding. Crying was combined with treatment, alternative treatment, and complementary treatment. Crying was replaced with irritability and then with colic and the above search was repeated.

Search process

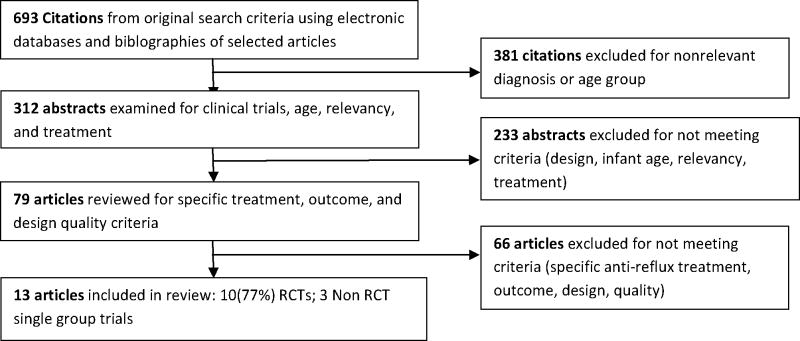

Figure 1 illustrates the selection process for the inclusion and exclusion of articles. Articles not meeting criteria were (a) reviews of the literature; (b) methods of action of H2RAs or PPIs; (c) anti-reflux medications other than H2RAs or PPIs; (d) samples including only preterm infants, children, adolescents, or adults; (e) sample age ranging from infant to adolescence or adulthood without clear distinction of the effects on the infant; (f) samples including infants with a chronic condition in addition to GERD; (g) infants displaying feeding problems but not GERD specifically; (h) irritability was not an outcome; (i) crying was not excessive (in studies addressing only irritability); (j) data collection or type of analysis of the irritability variable were not sufficiently explained to evaluate, or the sample or the methods used were too unclear to evaluate.

Figure 1.

Study Selection Process

Results

Description of Studies

A total of 13 studies that included 1,401 infants met the inclusion criteria (Table 1). Six studies were reports of pharmacologic treatment for infants with GERD, four were of nonpharmacologic treatment for GERD, and three were for treatment of irritability that was not associated with GERD. Studies were conducted in the United States (Keefe et al., 2006; Orenstein & McGowan, 2008; Orenstein et al., 2003; Vanderhoof, Moran, Harris, Merkel, & Orenstein, 2003), Australia (Jordan, Heine, Meehan, Catto-Smith, & Lubitz, 2006; Moore et al., 2003; Omari et al., 2009), Belgium (Chao & Vandenplas, 2007; Hegar, Rantos, Firmansyah, DeShepper, & Vandenplas, 2008), Turkey (Arikan, Alp, Gozum, Orbak, & Cifci, 2008), Wales (Don, McMahon, & Rossiter, 2002), the United States and Poland (Orenstein, Hassall, Furmaga-Jablonski, Atkinson, & Raanan, 2009), and the United States, Poland, and South Africa (Winter et al., 2010). The majority of studies were conducted in outpatient settings (n = 10; 77%); two studies were initiated in the hospital (Jordan et al., 2006; Omari et al., 2009) and one study was conducted in the hospital (Don et al., 2002). Approximately half (47%) of infants were female (gender was not reported in 1 study). Ethnicity and/or race was not reported in all studies conducted in the European countries (n = 7; 54%), and in one (8%) study conducted in the United States. In the remaining five studies race was mainly Caucasian (76%).

Table 1.

Effects of Interventions for Infants with Symptoms of GERD (arranged chronologically within treatment categories)

| Pharmacologic Intervention: Histamine-2 receptor antagonists (H2RA) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authors, Design & Setting | Infant Age Gender Race/Ethnicity | Inclusion Criteria Exclusion Criteria | Trial Length | Intervention Control | Outcome n/Sample n | Outcome |

|

Orenstein et al., 2003 RCT; parallel (Part 1) |

Age Range: 1.3–10.5 months Median: 5.3 months Female: 57% Race: 91% White |

Inclusion Criteria:

|

4 wks | All instructed in conservative measures Intervention: Famotidine 0.5mg/kg/d Comparison: Famotidine 1.0mg/kg/d |

Part 1: 27/35 Intention to treat |

Primary. Irritability & regurgitation (I-GERQ at baseline; parent recording of crying & regurgitation at weeks 2 & 4). No differences between groups in: Crying

|

| (Study 2) 8/35 | Insufficient sample to conduct comparisons for Study 2 | |||||

|

Jordan et al., 2006 RCT |

Age Range: 0.5–8.2 months Mean: 3.2 months Female: 46.6% Race/Ethnicity: Not reported |

Inclusion Criteria:

|

4 wks |

Intervention: Group A Ranitidine 3 mg/kg + cisipride 0.2mg/kg Placebo Group B Individualized consultation Group C |

84/127 cry diaries 93/127 maternal stress & depression surveys |

Primary. Crying (Nurse completed Baby Day Diary for 24 hrs [Barr et al., 1988] at baseline, parent completed at day 10 & week 4).

(Experience of Motherhood Questionnaire; EMQ [Astbury, 1994] at Baseline & week 4)

|

| Proton Pump Inhibitor | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authors, Design & Setting | Infant Age Gender Race/Ethnicity | Inclusion Criteria Exclusion Criteria | Trial Length | Intervention Control | Outcome n/Sample n | Outcome |

|

Moore et al., 2003 RCT; Crossover |

Age Range: 3–10.2 months M = 5.4 ± 2.1 months Female: 23% Race/Ethnicity: Not reported |

Inclusion Criteria:

|

2 weeks + 2 weeks |

Intervention: Omeprazole 10mg/day for weight < 10 kg and 10mg twice daily for weight > 10 kg Crossover Control: Identical appearing placebo without active drug |

30/34 |

Primary. Crying (Parents completed Baby Day Diary [Barr et al., 1988] completed for 5 days at baseline and at weeks 2 & 4).

Secondary. Reflux index (assessed at baseline and week 2)

|

|

Omari et al., 2009 Single Group Trial |

Age Range: 9–11 mos. M = 10 months (Corrected in preterm infants) 70% born preterm ≥23 wks gestational age Female: 50% Race/Ethnicity: Not reported |

Inclusion Criteria:

|

1 week |

Intervention: Esomeprazole. 05mg/k/d Control: NA |

25/26 20/26 (pH monitoring) |

Primary. (pH monitoring) Reflux index

GERD symptoms (Hospital staff or mother recorded symptoms in tick box, [crying/fussing, apnea, choking, arching, grimacing, gagging] for 24 hrs at baseline and day 8.

|

|

Orenstein et al., 2009 RCT; parallel |

Age Range: 4 to < 52 wks Median = 4 months (Preterm: corrected age) 73% born at term Female: 50% Race: 80% Caucasian |

Inclusion Criteria:

|

4 weeks |

Pretreatment: 2 weeks Conservative therapy: Treatment: 4 weeks Intervention: Lansoprazole 0.2–0.3mg/kg/d < 10 weeks old or 1.0 – 1.5 mg/kg/d > 10 weeks old Control: Placebo If no response after 1 wk, switched to open-label (n = 55) Posttreatment 4 weeks |

162/162 Intention to treat. Outcomes assessment at termination of blind treatment |

Primary. Crying (one parent completion of daily diary of number & duration of crying episodes). Responders = ≥ 50% reduction from baseline in percent feedings with crying episode or duration of minutes episodes of crying averaged across feedings. 54% in each group responded No difference between groups in:

GERD symptoms (per daily diary - % of feeds/week with: regurgitation; stopping feedings early; feeding refusal; arching back; coughing; wheezing; hoarseness).

|

|

Winter et al., 2010 Part 1: Single group trial Part 2: RCT; parallel |

Age Range: 4 to < 52 weeks Median = 5.1 months (Preterm: corrected age) 82% born at term Female: 36% Race: 66% Caucasian |

Inclusion Criteria:

|

Part 1:4 weeks Part 2: 4 weeks |

Pretreatment: 2 weeks Conservative therapy Part 1, Open label: 4 weeks Conservative measures, Contact with research staff every week by office visit or telephone call. Pantoprozole 1.2 mg/k/day Part 2, Double blind: 4 weeks Intervention: Conservative measures with Pantoprazole 1.2mg/k/day Control: Placebo |

Part 1: 106/129 Part 2 109/109 Intention to treat. |

Primary. Withdrawal Rate due to lack of efficacy in the double-blind phase (worsening of GERD symptoms, worsening esophagitis, maximal antacid use for 7 continuous days).

Withdrawal:

|

| Nonpharmacologic Interventions | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authors, Design & Setting | Infant Age Gender Race/Ethnicity | Inclusion Criteria Exclusion Criteria | Trial Length | Intervention Control | Outcome n/Sample n | Outcome |

|

Vanderhoof et al., 2003 RCT; parallel |

Age Range: 0.5 – 4.5 mo. M = 2 months Female: 50% Race/Ethnicity: Not reported |

Inclusion Criteria:

|

5 weeks |

Intervention: Enfamil AR Group 30% lactose in standard formula replaced with 2.3g pre-gelatinized, amylopectin rice starch/100mL Control: C Group Standard Enfamil formula |

97/104 |

Primary. Regurgitation (Baseline parent diary 2 days; 7 days for week 1, and 2 days/week for next 4 weeks).

Choke/gag/cough

|

|

Chao & Vandenplas, 2007 RCT; parallel |

Age Range: 2 to 4 mo. M = 3.2 months Female: 50% Race/Ethnicity Not reported |

Inclusion Criteria:

|

8 weeks |

Intervention, Group A: Cornstarch thickened formula Control, Group B: 25% strengthened Formula (5 parts formula added instead of 4 to 120 ml water) |

81/100 Unclear if intervention included 13 infants who experienced marked diarrhea, enteritis, or respiratory infection & whose data was not included in final analysis |

Primary. Gastric Emptying: (90-minute milk scintigraphy).

Ingested feeding volume:

|

|

Hegar et al., 2008 RCT; parallel |

Age Range: 1 to 3 months M = 1.5 months Female: 70% Race/Ethnicity: Not reported |

Inclusion Criteria:

|

4 weeks |

Intervention, Group C: Formula thickened with bean gum Control Group A: Standard infant formula Control Group B: 5g rice cereal added to 100ml standard formula |

60/60 |

Primary. Regurgitation (Daily parent diary for 4 weeks).

Formula intake increased in all groups (p = .0001).

|

|

Orenstein & McGowan, 2008 Single Group Trial |

Age Range: 1 to 10 months Median age = 3.2 months Female: 41% Race/Ethnicity 68% White 16% Black 16% Hispanic |

Inclusion Criteria:

|

2 weeks | Intervention: Conservative measures | 37/40 |

Primary. Scores on I-GERQ-R (completed by parents at baseline & at weeks 2 & 4).

|

| Nonpharmacologic Intervention for Infant Irritability Regardless of GERD Status | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Authors, Design & Setting | Age Gender Race/Ethnicity | Inclusion Criteria Exclusion Criteria | Trial Length | Intervention Control | Outcome n/Sample n | Outcome |

|

Don et al., 2002 Single Group Trial |

Age Range: < 6 months Mean age: 3 months Infant gender: Not reported Race/ethnicity: Not reported |

Inclusion criteria:

|

4 weeks | Intervention:Admission to Family Care Center in Wales. Individual plan of care. Parents taught to attune to infant cry and to respond appropriately & settling methods (patting, touch). Parent educated in variations of infant behavior. Counseling. | 109/155 |

Primary: Unsettled behavior (crying/fussing (Maternal completion of Barr Baby Day Diary [Barr et al., 1988] for 24 hrs on admission, at day 4, & week 4 after discharge. A 5-point Infant Difficultness Scale was completed at baseline & 4 weeks after discharge). Infants:

|

|

Keefe et al., 2006 RCT |

Age Range: 0.5 – 2 months M = 1.3 months Female: 54.6% Race: 75.6% White |

Inclusion criteria:

|

4 weeks |

Intervention: REST Routine Assist parents to regulate infant state, create predictable daily life, provide variety of touch, affirm parent competence, promote time for self Control: “Standard care” |

105/121 |

Primary. Amount ofInfant cry/fuss (Mothers recorded amount and intensity of crying on the Fussiness Rating Scale [Keefe et al., 2005] to measure unexplained crying at baseline, and 4 & 8 weeks after baseline).

|

|

Arikan et al., 2008 RCT |

Age Range: 4–12 wks M = 2.2 months 20% born preterm Female: 40% Race/Ethnicity: Not reported |

Inclusion Criteria:

|

1 week |

Interventions:

|

175/187 |

Primary. Amount of crying (Daily parent diary completed 1 week before and 1 week during intervention).

Massage (p = .009) decreased 1 hr. Sucrose (p = .0004) decreased 1.8 hr Herbal tea (p = .0003) decreased 1.9 hr Hydrolyzed formula (p = .000007) decreased 2.2 hr Control group: decreased 0.1 hr |

Note: GERD=Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease; GI=Gastrointestinal

Quality Assessment of the Studies

All authors read the articles and contributed to decisions about the quality of the studies. The Cochrane Risk of Bias Assessment (Higgins & Green, 2008) was used to assess the quality of the studies. Included in the Cochrane Risk of Bias Assessment are sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcomes, selective outcome reporting, and other sources of bias (See Table 1). Sequence generation was considered “adequate” if researchers stated that they used a computer-generated random number sequence, a random number table, coin toss, or other similar method. Allocation concealment was considered adequate if authors explained procedures for randomization that included central allocation and sequentially numbered opaque, sealed envelopes. Blinding was designated as “yes” if data collectors and parents were unaware of the treatment status. Blinding was designated “partial” if only the investigator or parent was unaware of treatment status. Incomplete outcome data was considered adequately addressed if there were no missing data, or if missing data were unlikely to be related to the outcome. The study was determined to be free of selective outcome reporting if all outcomes were discussed. Funding sources were considered a risk of bias when studies were funded by the company that produced the product being tested.

Diagnostic tools used in studies

The gold standard for the diagnosis of GERD in infants is the 24-hour pH monitoring to measure acid reflux. Other diagnostic measures, however, have been used to assess the presence of GERD: multiple intraluminal impedance (MII) to detect both acid and nonacid reflux episodes, and endoscopy and biopsy to diagnose esophagitis. Reflux index can be calculated from esophageal monitoring. The reflux index is the percentage of total recording time where the pH is less than 4 (Moore et al., 2003). Because these various types of diagnostic measures assess different facets of GERD, little correlation has been found between them (Salvatore, Hauser, Vandemaele, Novario, & Vandenplas, 2005; Vandenplas et al., 2005), confounding interpretation. A parent-completed questionnaire, the Gastroesophageal Reflux Questionnaire-Revised (I-GERQ-R) is used to evaluate for the presence of GERD. The 12 questions in the I-GERQ-R address the amount of reflux, discomfort attributed to reflux, crying or fussing, back arching, refusal or stopped feeding, hiccups, and apnea or color change (Kleinman et al., 2006). Psychometric properties of the I-GERQ-R were conducted in seven countries (Kleinman et al., 2006; Orenstein, 2010). Clinical symptoms reported to the provider by the parents also are used to support the diagnosis of GERD.

Studies Examining Pharmacologic Interventions for GERD

The six studies we reviewed are detailed in Table 1. Infants born preterm were included in four studies resulting in a wide range of gestational ages at birth (Orenstein et al., 2009; Orenstein et al., 2003; Omari et al., 2009; Winter et al., 2010). Gestational age at birth was not reported in two studies (Jordan et al., 2006; Moore et al., 2003). Infant age ranged from 2 weeks to 11 months with a mean or median of 3 to 10 months. GERD was diagnosed by clinical symptoms (Orenstein et al, 2003), or questionnaire (Orenstein et al, 2009; Winter et al., 2010), pH monitoring, biopsy, or endoscopy (Jordan et al., 2006; Moore et al., 2003; Omari et al., 2009). In three studies infants had previously and unsuccessfully been treated with anti-reflux medications (Omari et al., 2009; Orenstein et al., 2009; Orenstein et al., 2003). Sample sizes (26–162) were relatively small, although in four studies, a power analysis was reported (Moore et al., 2003; Orenstein et al., 2009; Orenstein et al., 2003; Winter et al., 2010). Duration of the trials was 1 to 4 weeks.

Infant irritability with GERD

Irritability was defined as the average daily amount of crying and/or fussiness in all studies. Diaries used for data collection included either amounts of daily crying/fussiness or frequency of bouts of crying/fussiness. In four studies, the diaries had not been validated as an instrument measuring irritability (Omari et al., 2009; Orenstein et al., 2009; Orenstein et al., 2003; Winter et al., 2010). Orenstein and colleagues (2003) used the irritability items from the I-GERQ-R. The individual items have not been validated as a tool to assess irritability. In subsequent visits mothers were asked to record the amount of crying that the infants had done in the past 2 weeks. Winter and colleagues (2010) used a modified version of The GERD Symptom Questionnaire (GSQ) reported to be valid to discriminate infants with GERD from healthy infants (Deal et al., 2005). Individual items had not been validated as a tool to assess irritability. Mothers were asked to record retrospectively how many times in the past 24 hours that the baby cried or fussed during and after feedings. Mothers in the Orenstein and colleagues study (2009) recorded number and duration of crying episodes during and within an hour after each feeding in a nonvalidated daily diary. Jordan and colleagues (2006) and Moore and colleagues (2003) used the Baby Day Diary that has adequate psychometrics for assessment of crying that includes correlation with auditory recordings of crying (r = .67, p < .03; Barr et al., 1988). The diary is divided into 5-minute blocks spanning a 24-hour period. Parents record the duration of crying and fussing by shading or drawing prescribed symbols in the blocks throughout the 24-hour period.

Collection times and data collectors varied among studies. Data was collected retrospectively (Orenstein, et al., 2003), or for 24 hours at pre-selected time points during the trial (Jordan et al., 2006), for five days at prescribed time periods (Moore et al., 2003), or throughout the duration of the trial (Orenstein et al., 2009, Winter et al., 2010). Data collectors in 2 studies were a combination of parents and nurses (Jordan et al., 2006; Omari et al., 2009).

Regardless of the sample, pharmacologic treatment, or placebo, the frequency or duration of irritability decreased in all studies by the end of the trial. Mean duration of irritability decreased by at least 20%.

Reflux

Reflux was examined in two of the pharmacologic treatment studies. Frequency of reflux decreased from baseline in both studies. No difference in frequency of reflux, however, was found between any of the treatment groups. Moore and colleagues (2003) and Omari and colleagues (2009) used pH monitoring to assess reflux after trials with PPIs. Moore and colleagues (2003) reported greater improvement in the reflux index after treatment with omeprazole than placebo (p < .001). In a single group trial, Omari and colleagues (2009) also found improvement in the reflux index and a decrease in frequency and duration of acid reflux episodes.

Safety

Four of the six studies reported on safety. Weekly physical assessment by the investigator, laboratory measurement, and parent report were the methods employed to evaluate safety. In a 4-week study of famotidine (Orenstein et al., 2003), most (n = 11, 32%) adverse effects were minor, such as agitation, head rubbing (as if the infant had a headache), somnolence, vomiting, and diarrhea. Omari and colleagues (2009) reported GI symptoms (constipation, diarrhea, and vomiting) with esomeprazole (n = 4, 16%) at the conclusion of the 7-day trial. A higher incidence of more serious lower respiratory infections was found with lansoprazole (p = .032) during 4 weeks of treatment (Orenstein et al., 2009). Winter and colleagues (2010), on the other hand, reported no difference between groups on pantoprazole versus placebo for events such as abnormal laboratory results, poor weight gain, respiratory infection, or worsening of GERD symptoms.

Summary

Findings from the studies showed that pharmacologic treatment decreased irritability and reflux as effectively as placebo or individualized consultation. The reflux index normalized and frequency of acid reflux bouts decreased better with anti-reflux medication, specifically PPIs. Adverse effects typically were mild with H2RAs and PPIs.

Studies Examining Nonpharmacologic Interventions for GERD

Studies (n = 4) of nonpharmacologic therapy investigated benefits of formulas, feeding modifications, or dietary supplements. Infants were born at term in three studies (Hegar et al., 2008; Orenstein & McGowan, 2008; Vanderhoof et al., 2003); this information was not reported by Chao & Vandenplas (2007). The age at enrollment was less than 5 months in three studies (Chao & Vandenplas 2007; Hegar et al., 2008; Vanderhoof et al., 2003) and 1 to 10 months in one study (Orenstein & McGowan, 2008). Mean or median age, however, was homogenous (1.5 to 3 months). Diagnosis of GERD was made with the I-GERQ-R, endoscopy, or pH monitoring (Orenstein & McGowan, 2008) and by clinical symptoms in the remaining three studies. Prior treatment for GERD symptoms was not reported. None of the RCTs for non-pharmacologic interventions included a power analysis. Duration of the trials was from 2 to 8 weeks.

Infant irritability with GERD

Diaries were generally poorly described, and validity was not reported for diaries for data collection of irritability, with the exception of the I-GERQ-R (Orenstein & McGowan, 2008). As stated previously, however, individual irritability items in the I-GERQ-R are not validated to assess irritability. As with the pharmacologic studies, data collection times varied from 2 to 8 weeks. Reporting of irritability typically was not detailed in these studies. Only Orenstein and McGowan (2008) reported duration of irritability. Parents in the Chao and Vandenplas (2007) study asked parents to record the frequency of irritability or crying in an undescribed daily diary. Parents in the Vanderhoof and colleagues (2003) study reported crying and fussing after feedings that they interpreted as pain or sleep disturbance. Hegar and colleagues (2008), comparing thickened formula with bean gum to rice, did not describe the daily diary except to state that parents recorded periods of sleep disturbance caused by irritability. Whether irritability decreased during the trial was not reported.

Irritability decreased in some infants in the three studies in which it was reported (Chao & Vandenplas, Orenstein & McGowan, 2008; Vanderhoof et al., 2003). Infants fed cornstarch or rice starch formulas showed a greater decrease in irritability than infants who were fed standard formula or strengthened standard formula (Chao and Vandenplas, 2007; Vanderhoof et al., 2003). In the single group trial using conservative therapy (feeding modifications, hypoallergenic or hydrolyzed formula, infant positioning, and elimination of smoking near the infant) irritability also decreased in some infants (Orenstein & McGowan, 2008).

Reflux

The same diaries and data collection schedules were used for this variable as for irritability. Infants fed formula thickened with corn or rice starch showed a greater decrease in frequency of reflux than infants fed standard formula (Chao and Vandenplas, 2007; Vanderhoof et al., 2003). Hegar and colleagues (2008) reported no difference in the reduction of frequency of reflux in infants fed standard formula or formula thickened with either bean gum or rice. Use of conservative measures also resulted in reduction in frequency of reflux although these measures were not compared to a control (Orenstein & McGowan, 2008).

Safety

Safety was a variable in only two studies. Vanderhoof and colleagues (2003) reported no group difference in adverse effects (diarrhea, constipation, gas). In the Chao and Vandenplas study (2007), 100 infants were monitored for 8 weeks, and 19 dropped from the study for developing adverse effects such as marked diarrhea, enteritis, or respiratory infection.

Summary

More decreases in irritability and reflux were noted for infants receiving formula thickened with cornstarch or rice starch than standard formula (even when strengthened). Unpleasant adverse effects, however, occurred with the cornstarch formula. GERD symptoms that included crying and reflux also decreased with conservative therapy.

Studies Examining Nonpharmacologic Interventions for Excessive Crying

Findings from the previously discussed studies suggest that the traditional pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatment for GERD, described in the aforementioned studies, may reduce crying in some, but not all, infants with symptoms of GERD. Perhaps measures that are effective with infants with excessive crying would be effective as adjunct therapy in infants with symptoms of GERD. Nonpharmacologic treatment for excessive crying (See Table 1) included massage, dietary supplements, and comprehensive treatment plans. In an RCT addressing only infant irritability, massage therapy and dietary supplements were compared to “standard care” that was undefined (Arikan et al., 2008). Mothers were taught to administer massage, but their technique was not monitored. Keefe and colleagues (2006) compared a comprehensive environmental treatment plan targeting infant irritability to a control group who received the standard of care for infant irritability. In another study, the benefit of an individualized multidisciplinary residential treatment plan was investigated (Don et al., 2002). Infants were born at term in one study (Keefe et al., 2006), while gestational age at birth was not reported in 2 studies (Arikan et al., 2008; Don et al., 2002). Infants in all studies were less than 6 months of age at enrollment with mean or median age of 1.3 to 3 months. The RCTs did not include a power analysis. Duration of the trials ranged from 1 to 4 weeks.

Keefe and colleagues (2006) asked mothers to rate their babies’ typical hours of daily crying and fussiness and intensity of the fussiness over the past week using the Fussiness Rating Scale (FRS). The FRS was used by the researchers in previous studies (Keefe, Barbosa, Froese-Fretz, Kotzer, & Lobo, 2005; Keefe, Froese-Fretz, & Kotzer, 1998; Keefe, Kotzer, Froese-Fretz, & Curtin, 1996) and was explained in detail. Mothers in the Don and colleagues (2002) study used the 24-hour Baby Day Diary (Barr et al., 1988) to record minutes of fussing and crying continuously. In Arikan and colleagues’ (2008) study, parents recorded the duration of crying time in a nonvalidated daily diary each time it occurred.

Data collection schedules varied. The timing of the parents’ recordings of the amount of irritability differed among studies. In one study parents recorded for a 24-hour period (Don et al., 2002), in another study parents reported retrospectively every week (Keefe et al., 2006), and in the third study, parents recorded continuously for 2 weeks (Arikan et al., 2008). The percentage of infants responding to treatment was not reported, but the duration of irritability decreased in infants receiving the interventions. In studies comparing an intervention to standard care, irritability decreased more in infants receiving the intervention, although in none of these studies was the treatment blinded.

Discussion

This review was conducted to assess the effectiveness of nonsurgical treatment on irritable behavior of infants with Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease (GERD). Infants less than 12 months of age with symptoms of GERD were studied for benefits of pharmacologic and non pharmacologic therapy on infant irritability and reduction of symptoms (other than irritability) with GERD.

Question #1 What are the benefits of pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatments on irritability in infants with symptoms of GERD?

Few studies have been conducted on the treatment of irritability in infants with GERD. This is especially surprising for pharmacologic studies, since many infants are treated with anti-reflux medications (Diaz et al., 2007; Barron et al., 2007).

Pharmacologic treatment of GERD consists of primarily H2RAs and PPIs. Six studies reported the effects of pharmacotherapy on GERD with crying as an outcome measure. Diaries often were used to evaluate the duration or frequency of infant irritability. Diversity in treatment, data collection methods, and reporting make comparisons difficult. Nonetheless, infant irritability significantly decreased in every study, generally after 2 to 4 weeks of treatment. In RCTs of pharmacologic treatment, however, placebo or an individualized treatment were just as effective as the H2RA or PPI. The effect of dosage was only studied in the report using famotidine, and, although there was a significant dose-related reduction in crying, there was no difference in crying at weeks 2 and 4 between groups. The authors speculated that the lack of difference may have been due to infants taking the higher dosage of medication (famotidine 1.0 mg/kg/d) or crying more at baseline.

Nonpharmacologic therapy for infants with and without GERD included conservative therapy (reduction of tobacco smoke, positioning, and feeding modification), alternative therapies, and individualized treatment plans (REST, Tresillian Family Centered Care Program). Feeding modifications included scheduling adjustments and feeding volume; hypoallergenic formula; formula thickened with rice cereal, bean gum, cornstarch, or rice starch. Alternative therapies were massage therapy, herbal tea, and a sucrose solution. The only nonpharmacologic treatments that did not show any effects were standard care and standard formula. Whether irritability was reduced with bean gum and rice cereal was not reported.

Sampling methods potentially confounded the results of the studies. Power analysis was conducted in 75% of the pharmacologic RCTs, but in none of the nonpharmacologic studies or in studies to reduce crying in infants without GERD. Studies without this analysis may have been underpowered, resulting in Type II error (i.e., more effectiveness may have been found over control conditions if an adequate sample was used). Studies in which infants born preterm and term were combined may have impacted the results of treatment effectiveness. For example, the benefits of treatment on irritability may have been less pronounced in infants born preterm, who have been shown to be less emotionally regulated than infants born at term (Feldman & Eidelman, 2009). It would have been more meaningful to separate the findings for these two groups of infants.

The wide range in postnatal age in approximately half of the studies also may have masked effects of treatment, especially when the sample size was small. Crying typically decreases in infants by the second half of the first year. This natural maturation would also make it more difficult to find differences based on treatment rather than normal development. Age-matched studies would have controlled for this confounder. It is possible that the older infants had developed a behavioral repertoire more resistant to change than that of younger infants. Also, prior treatment with anti-reflux medication for GERD was not reported in the nonpharmacologic studies reviewed.

Methods of diagnosing GERD varied. The I-GERQ-R or pH monitoring, endoscopy, or biopsy were used to diagnose GERD in the pharmacologic studies. When the reflux index was utilized for the presence of GERD, infants had ranges from 5% to greater than 10%, indicating less severe to more severe acid reflux. In the nonpharmacologic studies, symptoms were used to diagnose GERD. The lack of uniformity in diagnostic measures (e.g., crying versus back arching as a sign) could have made a difference in the results of treatment effectiveness. Findings from these studies, however, were remarkably similar using various symptoms of GERD.

Other biases potentially confounded the results. For example, blinding is more easily done with pharmacologic and formula studies than with behavioral interventions. In studies without a control group, and the behavioral studies, parents aware that they were receiving the intervention might be more likely to respond favorably than if they were blind to the treatment group. Funding bias also may have been operating. In 54% of the studies, funding was provided by the companies that produced the anti-reflux medication, the formula, or the hospital sponsoring the treatment (See Table 2).

Table 2.

Bias Assessment

| Study Design | Sequence Generation | Allocation Concealment | Blinding | Incomplete outcome data addressed? % Follow-up |

Free of selective outcome reporting? | Other Sources of Bias Or Threats to Validity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacologic Intervention for Infants with Symptoms of GERD | ||||||

| Orenstein et al., (2003) RCT: parallel Part 1 Drug dosage compared | Unclear | Unclear | Part 1 Yes, to dose of drug |

Part 1 Yes/No Safety: 97% Irritability: 77% |

Part 1 Yes |

|

| Part 2 RCT: Drug compared to placebo | Part 2 Yes |

Part 2 No 23% |

Part 2 No | Part 2: Sample too small for data analysis | ||

| Jordan, et al., 2006 RCT | Unclear | Unclear | Yes, Pharmacologic arm No, IMHC arm |

No 66% Cry diary 73% Maternal measures |

No |

|

|

Moore et al., 2003 Crossover |

Unclear | Unclear | Yes |

No 88% |

Yes |

|

|

Omari et al., 2009 Single-group trial |

NA | NA | No |

Yes 97% |

Yes |

|

|

Orenstein et al., 2009 RCT; parallel |

Adequate | Adequate | Yes |

Yes Intention to treat analysis |

Yes |

|

| Winter et al., 2010 | Unclear | Unclear | Part 1 No Part 2 Unclear |

Yes Intention to treat |

Yes |

|

| Nonpharmacologic Interventions for Infants with Symptoms of GERD | ||||||

|

Vanderhoof, et al., 2003 RCT; parallel |

Unclear | Unclear | Yes |

Yes 93% |

No Sleep data in ¾ of sample |

|

|

Chao & Vandenplas, 2007 RCT; parallel |

Unclear | Unclear | Unclear |

No 80% |

Yes |

|

|

Hegar et al., 2008 RCT; parallel |

Adequate | Unclear | Yes |

Yes 100% |

Yes |

|

|

Orenstein & McGowan, 2008 Single group trial |

NA | NA | No |

Yes 93% |

Yes |

|

| Nonpharmacologic Intervention for Infant Irritability Regardless of GERD Status | ||||||

|

Don et al., 2002 Single group trial |

NA | NA | No |

No 70% |

Yes |

|

|

Keefe et al., 2006 RCT |

Adequate | Unclear | Partial, Data collectors |

Yes 91% |

Yes | No |

|

Arikan et al., 2008 RCT |

Unclear | Unclear | Not in formula group |

Yes 94% |

Yes |

|

NA= not applicable

Note. GERD=Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease; GI=Gastrointestinal; NA=not applicable; IMHC=Infant Mental Health Consultation (Data from Higgins, J. P. T., & Green, S. (Eds.). (2008). Cochrane Handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.0.1.

The Cochrane Collaboration. Available from www.cochrane-handbook.org.)

Measurement of irritability using instruments validated to assess irritability rarely was done, threatening validity of the findings. A risk of recording bias existed in studies in which nursing staff recorded infant irritability because busy nurses are likely to miss some of the irritability episodes. In three studies, data were collected retrospectively, risking the accuracy of the data due to issues with recall (See Table 1). In the nonpharmacologic studies for infants with symptoms of GERD, data on irritability was not detailed, making drawing conclusions difficult.

Question #2 What is the efficacy of pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic treatments for reflux, acid reflux, and safety?

In 60% of the studies assessing treatment for GERD, data collected for reflux were obtained by reports on the same diaries as irritability. Frequency and volume of reflux decreased in the pharmacologic trials but were similar between placebo and individualized care. It is not surprising that acid reflux decreased with the use of anti-reflux medication (Tighe et al., 2009; Wallace & Sharkey, 2011). In the nonpharmacologic studies, reflux decreased more with rice starch and cornstarch than with standard formula or strengthened standard formula as previously reported (Craig et al., 2004).

Anti-reflux medications have adverse effects. It is therefore notable that although H2RAs and PPIs may be ordered as long as 8 months for infants (Diaz et al, 2007), the trials assessing safety typically lasted only 1 to 4 weeks (Omari et al., 2009; Orenstein et al., 2009; Orenstein et al., 2003). With the exception of lower respiratory infection (Orenstein et al., 2009), adverse effects from these drugs were minor. However, no matter how minor, these effects could increase the discomfort of the infant and potentially increase irritability. The effects of extended administration and long-term effects of these medications on young infants remain unknown. In their review, Craig and colleagues (2004) indicated that coughing and diarrhea were adverse effects of thickened formula. Omari and colleagues (2009) had similar findings, but infants with uncomfortable gastrointestinal and respiratory symptoms were omitted from analysis.

Conclusions and Suggestions for Further Research

More research on which treatment (or combination of treatments) could be effective for infants is needed. Review of the literature on the treatment for the signs and symptoms of GERD in infants suggests that a variety of interventions may decrease infant irritability and reflux. There is no definitive treatment that became clear as a result of this review. Were the infants who showed a reduction in crying the same infants who showed a reduction in reflux? Also, does the act of disrupting the household routine with any intervention interfere with the crying cycle, resulting in reduction of irritability? Research on effectiveness of treatment for irritability, in infants with GERD, is scant. The research in which irritability is a variable has many confounds, such as the influence of the family on infant irritability or temperament of the infant. These confounds are areas for future research.

Limitations and Future Research

The research discussed in this review suggests that some infants are helped by certain interventions, but which specific intervention is best for which infant is not known at this time. Limitations in the studies discussed in this review suggest areas for future research:

Enroll infant participants with similar gestational age at birth (e.g., born at term or preterm) participants and restrict the range of postnatal age. If a wide range of gestational and postnatal age exists, enroll an adequate sample so that results can be reported separately for each age group;

Use validated data collection instruments and collect behavioral data for several days at each collection period. Provide a detailed explanation of the tool and data collection procedure. Monitor the data collectors;

Design studies that incorporate more than one intervention. For instance, comparing a behavioral intervention, a pharmacologic intervention, and a combination of the behavioral and pharmacologic intervention would provide simultaneous comparison of effectiveness;

Monitor the safety of pharmacologic treatments and thickened formulas for 2 to 3 months so that long-term safety can be determined;

Study prospectively, beginning soon after birth and continuing through 3 to 4 months of age, the development of irritability in GERD.

How Do I Apply This Evidence to Nursing Practice?

Knowledge of the effectiveness of individual treatments and the gaps in research are crucial for anticipatory guidance and prescription of pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions. Advanced practice nurses additionally are in a position to suggest a combination of treatments and to participate in or conduct research that would help close the gaps. More research needs to be conducted to determine the most effective individualized treatment for infants with GERD. Findings from this review, however, suggest that unless the goal is to reduce acid reflux, conservative and alternative therapies are as effective in reducing irritability as anti-reflux medications without the adverse effects. Even minor adverse effects could increase irritability in infants. Individualized and conservative treatment may be a better first-line approach than antireflux medication. Nurses working in the hospitals, clinics, and pediatric offices also have a role in treatment of infants with the common phenomena of irritability as a GERD symptom. Discussion with parents and observation of the infant and maternal-infant interactions can assist in compiling a detailed record of history, symptoms, and treatment effectiveness.

Acknowledgments

The paper was partially supported by a research grant from National Institute of Nursing Research, R21NR011069-01A2

Footnotes

Disclosure. The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interests.

Contributor Information

Madalynn Neu, Email: Madalynn.Neu@UCdenver.edu, University of Colorado College of Nursing, 13120 E. 19thAve, C-288, Aurora C0 80045, Phone: (303) 724-8550, Fax: 303-724-8560.

Elizabeth Corwin, University of Colorado College of Nursing, 13120 E. 19thAve, C-288, Aurora CO 80045.

Suzanne C. Lareau, University of Colorado College of Nursing, 13120 E. 19thAve, C-288, Aurora CO 80045.

Cassandra Marcheggiani-Howard, University of Colorado College of Nursing, 13120 E. 19thAve, C-288, Aurora C0 80045.

References

- Arikan D, Apl H, Gozum S, Orbak Z, Cifci EK. Effectiveness of massage, sucrose solution, herbal tea or hydrolysed formula in the treatment of infant colic. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2008;17:1754–1761. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2007.02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astbury J. Making motherhood visible: The experience of motherhood questionnaire. Journal of Reproduction and Infant Psychology. 1994;12:79–88. doi: 10.1080/02646839408408871. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barr RG, Kramer MS, Boisjoly C, Leduc DG, McVey-White L, Pless IB. Parental diary of infant cry and fuss behaviour. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 1988;63:380–387. doi: 10.1136/adc.63.4.380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barron JJ, Tan H, Spalding J, Bakst AW, Singer J. Proton pump inhibitor utilization patterns in infants. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 2007;45:421–427. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31812e0149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll AE, Garrison MM, Christakis DA. A systematic review of nonpharmacological and nonsurgical therapies for gastroesophageal reflux in infants. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 2002;156:109–113. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.156.2.109. Retrieved from http://archpedi.ama-assn.org. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao HC, Vandenplas Y. Comparison of the effect of a cornstarch thickened formula and strengthened regular formula on regurgitation, gastric-emptying and weight gain in infantile regurgitation. Diseases of the esophagus. 2007;20:155–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2007.00662x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colin DR, Hassall E. Gastroesophageal Reflux. In: Klenman R, Goulet O-J, Mieli-Vergani G, Sanderson I, Sherman P, Shneider B, editors. Walker’s pediatric gastrointestinal disease. 5. Ontario, Canada: BC Decker; 2008. pp. 99–100. [Google Scholar]

- Craig WR, Hanlon-Dearman A, Sinclair C, Taback SP, Moffatt M. Metoclopramide, thickened feedings, and positioning for gastro-esophageal reflux in children under two years (Review) The Cochrane Library. John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deal L, Gold BD, Gremse DA, Winter HS, Peters SB, Fraga PD, Fitzgerald JF. Age-specific questionnaires distinguish GERD symptom frequency and severity in infants and young children: Development and initial validation. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 2005;41:178–185. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000172885.77795.0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz DM, Winter HS, Colletti RB, Ferry GD, Rudolph CD, Czinn SJ, Gold BD. Knowledge, attitudes and practice styles of North American pediatricians regarding gastroesophageal reflux disease. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 2007;45:56–64. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e318054b0dd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Don N, McMahon C, Rossiter C. Effectiveness of an individualized multidisciplinary program for managing unsettled infants. Journal of Pediatric and Child Health. 2002;38:563–567. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.2002.00042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman R, Eidelman AI. Biological and environmental initial conditions shape the trajectories of cognitive and social-emotional development across the first years of life. Developmental Science. 2009;12:194. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2008.00761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hegar B, Rantos R, Firmansyah A, DeShepper J, Vandenplas Y. Natural evolution of infantile regurgitation versus the efficacy of thickened formula. Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 2008;47:26–30. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e31815eeae9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heine RG, Jordan B, Lubitz L, Meehan M, Catto-Smith AG. Clinical predictors of pathological gastro-esophageal reflux in infants with persistent distress. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. 2006;42:134–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2006.00812.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higginbotham TW. Effectiveness and safety of proton pump inhibitors in infantile gastroesophageal reflux disease. The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 2010;44:572–576. doi: 10.1345/aph.1M519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.0.1. The Cochrane Collaboration. 2008 available from www.cochrane-handbook.org.

- Horvath A, Dziechciarz P, Szajewska H. The effect of thickened-feed interventions on gastroesophageal reflux in infants: Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized, controlled trials. Pediatrics. 2008;122:e1268–e1277. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan B, Heine RG, Meehan M, Catto-Smith AG, Lubitz L. Effect of medication, placebo and infant mental health intervention on persistent crying: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Pediatrics & Child Health. 2006;42:49–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2006.00786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keefe MR, Barbosa GA, Froese-Fretz A, Kotzer AM, Lobo M. An intervention program for families with irritable infants. American Journal of Maternal Child Nursing. 2005;30:230–236. doi: 10.1097/00005721-200507000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keefe MR, Froese-Fretz A, Kotzer AM. Newborn predictors of infant irritability. Journal of Obstetric Gynecologic and Neonatal Nursing. 1998;27:513–520. doi: 10.1111/j.1552-6909.1998.tb02617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keefe MR, Kotzer AM, Froese-Fretz A, Curtin M. A longitudinal comparison of irritable and nonirritable infants. Nursing Research. 1996;45:4–9. doi: 10.1097/00006199-199601000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keefe MR, Lobo ML, Froese-Fretz A, Kotzer AM, Barbosa GA, Dudley WN. Effectiveness of an intervention for colic. Clinical Pediatrics. 2006;45:123–133. doi: 10.1077/000992280604500203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleinman L, Rothman M, Strauss R, Orenstein SR, Nelson S, Vandenplas Y, Revicki DA. The Infant Gastroesophageal Reflux Questionnaire Revised: Development and validation as an evaluative instrument. Clinical Gastroenterolgy and Hepatology. 2006;4:588–596. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin AJ, Pratt N, Kennedy JD, Ryan P, Ruffin RE, Miles H, Marley J. Natural history and familial relationships of infant spilling to 9 years of age. Pediatrics. 2002;109:1061–1067. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.6.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathisen B, Worrall L, Masel J, Wall C, Shepherd RW. Feeding problems in infants with gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: A controlled study. Journal of Pediatric Child Health. 1999;35:163–169. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.1999.t01-1-00334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore DJ, Tao B, Lines DL, Hirte C, Heddle ML, Davidson GP. Double-blind placebo-controlled trial of omeprazole in irritable infants with gastroesophageal reflux. Journal of Pediatrics. 2003;143:219–223. doi: 10.1067/S0022-3476(03)00207-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson SP, Chen EH, Syniar GM, Christoffel KK. Prevalence of symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux during infancy. A pediatric practice-based survey. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 1997;151:569–572. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1997.02170430035007. Retrieved from http://archpedi.ama-assn.org. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omari TI, Lundborg P, Sandstrom M, Bondarov P, Fjellman M, Haslam R, Davidson G. Pharmacodynamics and systemic exposure of esomeprazole in preterm infants and term infants with gastroesophageal reflux disease. Journal of Pediatrics. 2009;155:222–228. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orenstein SR. Symptoms and reflux in infants: Infant Gastroesophageal reflux questionnaire revised (I-GERQ-R) - - utility for symptom tracking and diagnosis. Current Gastroenterology Reports. 2010;12:431–436. doi: 10.1007/s11894-010-0140-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orenstein SR, Hassall E, Furmaga-Jablonski W, Atkinson S, Raanan R. Multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial assessing the efficacy and safety of proton pump inhibitor lansoprazole in infants with symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Journal of Pediatrics. 2009;154:514–520. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2008.09.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orenstein SR, McGowan JD. Efficacy of conservative therapy as taught in the primary care setting for symptoms suggesting infant gastroesophageal reflux. Journal of Pediatrics. 2008;152:310–314. doi: 10.1016/j.peds.2007.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orenstein SR, Shalaby TM, Devandry SN, Liacouras CA, Czinn SJ, Dice JE, Stauffer LA. Famotidine for infant gastro-oesophageal reflux: A multi-centre, randomized, placebo-controlled, withdrawal trial. Alimentary Pharmacology andTherapeutics. 2003;17:1097–1107. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvatore S, Hauser B, Vandemaele K, Novario R, Vandenplas Y. Gastroesophageal reflux disease in infants: How much is predictable with questionnaires, pH-metry, endoscopy and histology? Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 2005;40:210–215. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200502000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz KF, Altman DG, Moher D, Consort Group. CONSORT 2010 statement: Updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomized trials. BMC Medicine. 2010;8:18. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-8-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman PM, Hassall E, Fagundes-Neto U, Gold BD, Kato S, Koletzko S, Vandenplas Y. A global, evidence-based consensus on the definition of gastroesophageal reflux disease in the pediatric population. The American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2009;104:1278–1295. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St James-Roberts I. Infant crying and sleeping: Helping parents to prevent and manage problems. Primary Care: Clinics in Office Practice. 2008;35 doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2008.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talvik T, Alexander RC, Talvik T. Shaken baby syndrome and a baby’s cry. ActaPaediatrica. 2008;97:782–785. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2008.00778.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tighe MP, Afzal NA, Bevan A, Beattie RM. Current pharmacological management of gastro-esophageal reflux in children: An evidence-based systematic review. Paediatric Drugs. 2009;11:185–202. doi: 10.2165/00148581-200911030-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Underdown A, Barlow J, Chung V, Stewart-Brown S. Massage intervention for promoting mental and physical health in infants aged under six months. Cochrane Database Systematic Review. 2006;18(4):CD005038. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005038.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenplas Y, Badriul H, Verghote M, Hauser B, Kaufman L. Oesophageal pH monitoring and reflux oesophagitis in irritable infants. European Journal of Pediatrics. 2004;163:300–304. doi: 10.1007/s00431-004-1403-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenplas Y, Salvatore S, Hauser B. The diagnosis and management of gastro-oesophageal reflux in infants. Early Human Development. 2005;81:1011–1024. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2005.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanderhoof JA, Moran JR, Harris C, Merkel KL, Orenstein SR. Efficacy of a pre-thickened infant formula: A multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled parallel group trial in 104 infants with symptomatic gastroesophageal reflux. Clinical Pediatrics. 2003;42:483–495. doi: 10.1177/000992280304200602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace JL, Sharkey KA. Pharmacotherapy of gastric acidity, peptic ulcers and gastroesophageal reflux disease. In: Brunton L, editor. Goodman and Gilman’s the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 12. New York, NY: McGraw Hill; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Winter H, Kum-Nji P, Mahomedy SH, Kierkus J, Hinz M, Li H, Maguire MK, Comer GM. Efficacy and safety of pantoprazole delayed-release granules for oral suspension in a placebo-controlled treatment-withdrawal study in infants 1–11 months old with symptomatic GERD. Journal of pediatric gastroenterology and nutrition. 2010;50:609–618. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181c2bf41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]