Abstract

Background and Objectives:

The acute-phase reactant C-reactive protein (CRP) has been shown to reflect systemic and vascular inflammation and to predict future cardiovascular events. The objective of this study was to evaluate the prognostic value of CRP in predicting cardiovascular outcome in patients presenting with acute coronary syndromes.

Patients and Methods:

This prospective, single-centered study was carried out by the Department of Pathology in collaboration with the Department of Cardiology, Bolan Medical College Complex Quetta, Balochistan, Pakistan from January 2009 to December 2009. We studied 963 consecutive patients presenting with chest pain to Accident and Emergency Department. Patients were divided into four groups. Group-1 comprised patients with unstable angina; group-2 included patients with acute ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI); group-3 comprised patients with Non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (Non-STEMI) and group-4 was the control group. All four groups were followed-up for 90 days for occurrence of cardiovascular events.

Results:

The CRP was elevated (>3 mg/L) among 27.6% patients in Group-1; 70.9% in group- 2; 77.9% in group-3 and 5.3% in the control group. Among cases with elevated CRP, 92.1% had a cardiac event compared to 34.3% among patients with CRP £3 mg/L (P < 0.0001). The mortality was significantly higher (P < 0.0001) in group-2 (8.9%) and group-3 (11.9%) as compared to group-1 (2.1%). There was no cardiac event or mortality in Group-4.

Conclusions:

Elevated CRP is a predictor of adverse outcome in patients with acute coronary syndromes and helps in identifying patients who may be at risk of cardiovascular complications.

Keywords: Cardiovascular disease, chest pain, coronary events, C-reactive protein, CRP

INTRODUCTION

The term “acute coronary syndrome” (ACS) encompasses a range of thrombotic coronary artery diseases, including unstable angina (UA), and both ST – segment elevation (STEMI) and Non-ST – segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), mostly induced by local coronary thrombosis as an acute complication of atherosclerosis.[1] Patients with an acute coronary syndrome have a high risk of suffering subsequent cardiac events.[2–4]

Coronary plaque disruption, with consequent platelet aggregation and thrombosis, is the most important mechanism by which atherosclerosis leads to the acute ischemic syndromes of unstable angina, acute myocardial infarction, and sudden death.[5]

With growing evidence that atherosclerosis is an inflammatory process, several plasma markers of inflammation have been evaluated as potential tools for the prediction of coronary events.[6] These markers of inflammation include serum amyloid A, interleukin – 6, homocysteines, fibrinogen levels, fibrinolytic capacity, apolipoprotein – A, apolipoprotein B-100, lipoprotein (a) and C-reactive protein (CRP).[7]

Increased concentrations of CRP have been reported in unstable angina[8] and in acute myocardial infarction.[9] Liuzzo and associates[10] have shown that concentrations of CRP and serum amyloid A in unstable angina increase independently of myocardial cell injury. They also reported that higher concentrations of CRP at the time of hospital admission (>3.0 mg/l) were predictive of a poor outcome in unstable angina.

CRP has been shown to predict risk in a wide variety of clinical settings; it has incremental value in addition to standard lipid screening for primary prevention.[11–13] A recent analysis by Chew et al.[14] shows that CRP predicts the risk of death or myocardial infarction at 30 days among patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. CRP was found to be independently associated with the recurrence of cardiovascular events and with death in the mid to long term.[15,16] It has been suggested that CRP may not only be a marker of generalized inflammation but directly and actively participates in both atherogenesis[17,18] and atheromatous plaque disruption.[19]

The aim of the present study was to evaluate the prognostic value of CRP in predicting cardiovascular outcome in patients presenting with acute coronary syndromes.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This prospective study was conducted by the Department of Pathology in collaboration with the Department of Cardiology, Bolan Medical College Complex, Quetta, Pakistan, between January and December 2009. A total of 963 consecutive patients presenting with chest pain were enrolled in the study. All patients were assessed by a detailed history and physical examination and relevant laboratory investigations to document presence of ACS. Patients who presented with history of typical chest pain and ST elevation or depression of >0.1 mV in two concordant ECG leads, or clinical picture of unstable angina were included.

The exclusion criteria were acute myocardial infarction within previous month,[20] inflammatory or neoplastic conditions likely to be associated with an elevated CRP and patients with valvular heart disease, hepatic failure and renal failure.

Patients were divided into four groups. Group-1 included 232 patients with a final diagnosis of unstable angina (men 160; women 72; mean age 53.6 ± 2.8 years); Group-2 included 258 patients with a final diagnosis of acute ST elevation myocardial infarction (men 182; women 76; mean age 54.4 ± 4.7 years); Group-3 included 286 patients with a final diagnosis of acute Non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (men 201; women 85; mean age 52.8 ± 5.2 years) and Group-4 was a control group which included 187 patients (men 112; women 75; mean age 53.7 ± 4.9 years). The control group included patients, who initially presented with chest pain but were found to be non-cardiac in origin on the basis of unremarkable serial ECGs and normal cardiac markers. There was no evidence of any infection, inflammation, malignancy, heart failure or valvular heart disease in these patients.

Venous blood under aseptic conditions was withdrawn from patients at the time of admission. The blood samples were shifted to a tube and clotted at room temperature. The tube was centrifuged for 5 minutes and the serum was separated for CRP, CK, CK-MB and Troponin T.

CK-MB was measured immunochemically (ACS: 180 analyzer: Bayer)[21] The upper reference limit was 7.5 μg/L and the assay was linear from 0 to 500 μg/L. The Troponin T was measured by ELISA on an ES300 analyzer (Boehring Mannheim)[20] The upper reference limit was 0.4 μg/L and the assay was linear from 0 to 15 μg/L.

CRP was measured with nephelometric assay (Boehring Diagnostics)[22] The detection limit was 0.2 mg/L, the assay was linear from 0.2 to 230 mg/L, and the CV was <3% at a concentration of 2 mg/L. The 95th percentile in 120 healthy donors in our institution was established at 3.0 mg/L.

A 90-day follow-up was arranged by telephonic interview either with the patients or their relatives. All patients were studied prospectively without knowledge of the CRP levels for cardiovascular complications including mortality, (re-) myocardial infarction, recurrent unstable angina or heart failure.

The diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction was established according to the WHO criteria,[23] with a history of chest pain lasting >20 minutes, characteristic ECG alterations, and peak CK-MB above 14 μg/L (twice the upper limit of normal or previous elevated value) or positive troponin T (>0.4 ng/ml). Acute Non-ST elevation myocardial infarction was considered present when peak CK-MB exceeded 14 μg/L and no new Q-waves developed on the electrocardiogram. Unstable angina was defined as with typical chest pain at rest (usually more than 20 minutes), new onset of exertional chest pain with marked limitation of ordinary physical activity, or recent (<2 months) increase in the severity of angina.[5] with a peak CK-MB above the upper limit of normal (7.0 μg/L) but below the predefined limit for acute myocardial infarction (as were patients without CK-MB elevation).

Cardiac death was defined as a death due to myocardial infarction, cardiac arrhythmias (sustained ventricular tachycardia, ventricular fibrillation and supraventricular tachycardia with hemodynamic compromise), cardiogenic shock or congestive cardiac failure.

All patients gave written informed consent for participation in the study.

Statistical analysis was done by SPSS version 14.0 in calculating the frequency, percentages and the Chi-square.

RESULTS

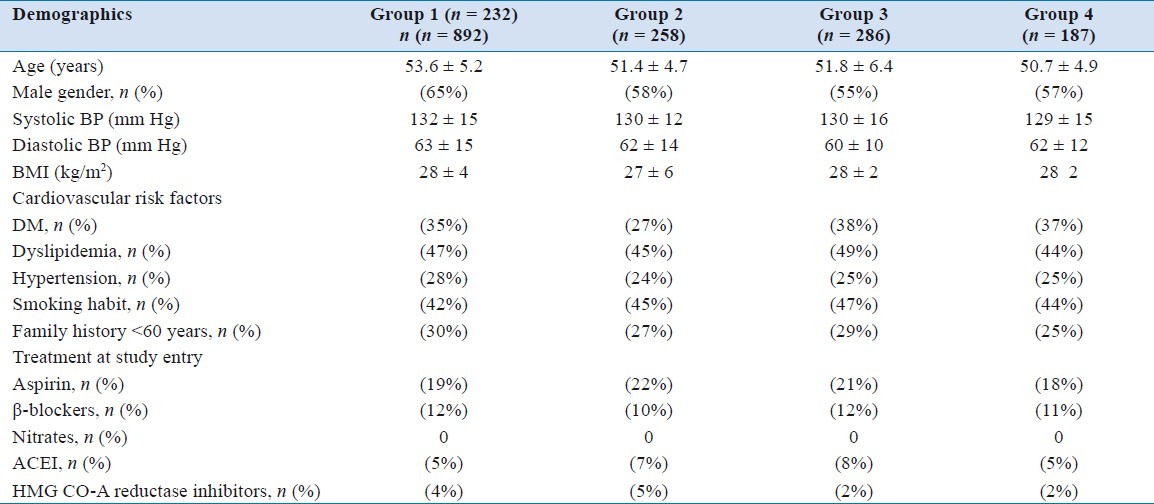

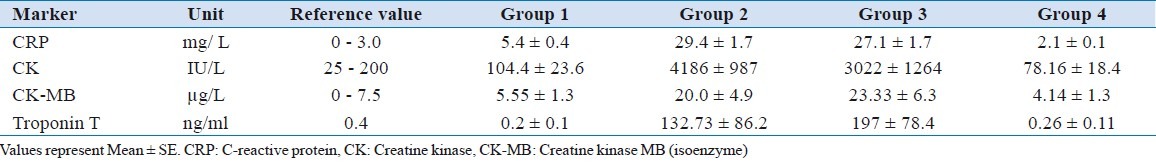

The baseline characteristics of the patients in different groups are given in [Table 1]. The values of CRP, CK, CK-MB and Troponin-T in each group are shown in [Table 2]. The CRP levels were significantly higher in group-2 and group-3 as compared to group-1 and group-4 (P < 0.00001).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study population

Table 2.

Mean values of various markers in different groups

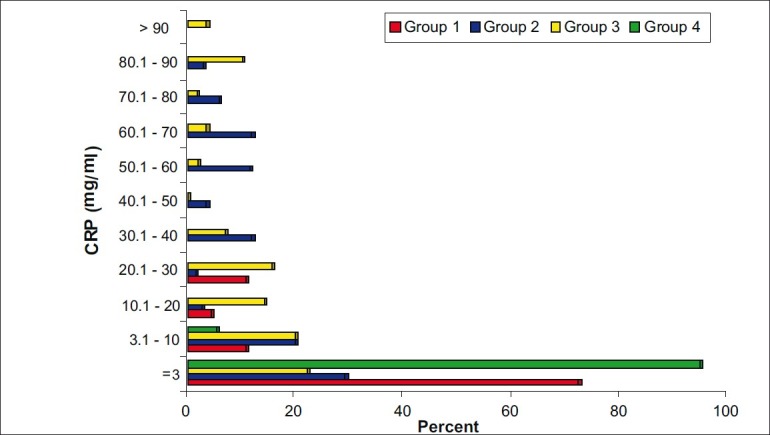

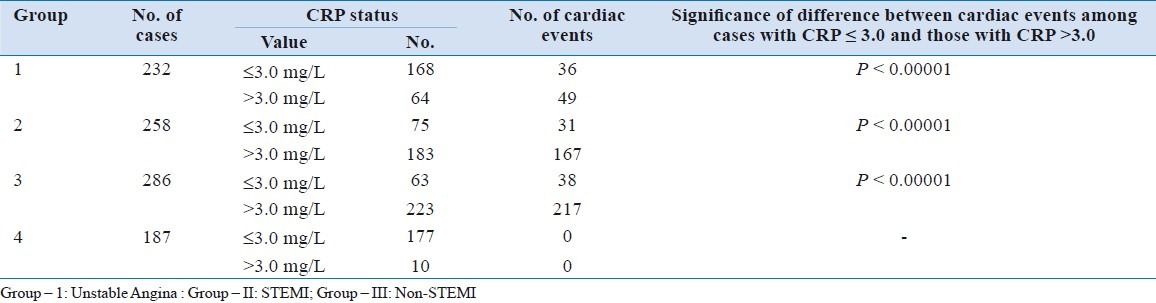

CRP levels ranged from 0.5 to 95 mg/ml [Figure 1]. The overall mean ± SE was 17.6 ± 7.96 mg/ml (95% CI = 1.66 - 33.6). The distribution of cardiac events among different groups is shown in [Table 3] while [Table 4] depicts the incidence of cardiac events according to CRP level in each group.

Figure 1.

Distribution of CRP among various groups

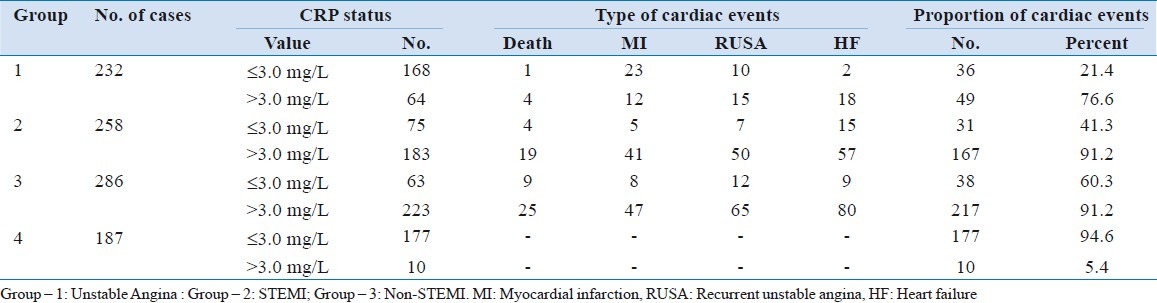

Table 3.

Distribution of cardiac events according to CRP levels

Table 4.

Significance of difference between occurrences of cardiac events among various groups

In Group-1, at the time of hospital admission, the CRP levels were >3.0 mg/L in 64 (28%) patients. The mean±SE was 5.43±0.48 mg/L. In Group-2, the CRP levels were >3.0 mg/L in 183 (71%) of patients. The mean±SE was 29.4±1.73 mg/L. In Group-3, CRP levels were >3.0 in 223 (78%) of the patients and mean ± SE was 27.1±1.67 mg/L. In Group 4 (Control Group), the CRP levels at the time of admission were >3.0 mg/L in 19 (10%) of the patients. The mean±SE was 2.16 0.11 mg/L.

A 90-day follow-up was done in all cases. In Group-1, 35 (15%) patients suffered acute myocardial infarction, 5 (2%) died of a coronary event, 25 (10.8%) had recurrent angina and 20 (12%) developed heart failure in the follow-up. Out of 168 patients with CRP £3 mg/L, 21.4% developed a cardiac event, while the proportion of those developing cardiac event among 64 patients with a CRP >3 mg/L was much higher (76.6%). The difference was statistically significant (P < 0.0001). In Group-2, 46 (17.8%) suffered another MI, 23 (8.9%) died of a coronary event, 57 (22.1%) suffered angina and 72 (27.9%) developed heart failure in the follow-up. The CRP levels were elevated in 167 (84%) out of these 198 patients. Out of 75 patients, who had CRP £ 41.3% had a cardiac event compared to 84.3% of those, who had CRP >3 mg/L (P < 0.0001). In Group-3, 55 (19.2%) suffered another MI, 34 (11.9%) died of a coronary event, 77(26.9%) suffered angina and 89 (31.1%) patients developed heart failure. Among those with CRP £3 mg/L, 60.3% patients suffered a cardiac event, while their proportion was 91.2% in those with CRP >3 mg/L (P < 0.0001). In Group-4, no coronary events were recorded in the follow-up period.

DISCUSSION

The present study shows that the acute phase reactant, CRP, is significantly elevated in patients with acute coronary syndromes compared to the control group. The number of patients with CRP elevations was much higher in Group-2 and 3 (71% and 78%) vs Group-1 (28%). The CRP levels were much more significant in Group-2 and 3 compared to Group-1 and 4. The mean CRP levels in Group-2 and 3 were 29.26 and 31.56 as compared to Group-1 and Group-4 where the mean CRP were 9.22 and 3.78, respectively. It was seen from the study that the CRP levels were more elevated in patients with Non-STEMI in comparison to STEMI, signifying a greater degree of inflammation and probably myocardial damage as well.

The present study results are comparable to the studies by Cavusoglu et al.[24] and Tomado et al.[25] who demonstrated that the CRP concentrations in patients presenting with acute coronary syndromes, within 6 hours of onset of symptoms were significantly higher as compared to the Control Group. The inflammatory process has been shown to be one of the mechanisms causing plaque rupture leading to elevated CRP levels in less than 6 hours in patients with acute coronary syndrome[21] In patients presenting with ACS, hsCRP concentrations are more than 10-fold higher than in patients with stable coronary disease or no known coronary disease.[8] In prior studies, increased concentrations of hsCRP have been shown to be associated with mortality in patients with UA and NSTEMI.[10,14,16,26] There are few data regarding hsCRP concentrations and the risk of heart failure in patients with ACS. Several studies found a relationship between increased concentrations of hsCRP and future episodes of heart failure among elderly patients with no known cardiovascular disease,[27] between hsCRP and heart failure in patients with STEMI,[28] or an association between hsCRP and heart failure when these variables were used as a part of a composite endpoint in patients with ACS.[29,30] In the present study, the relationship between even mild increases in baseline CRP was strongly and independently associated with the development of heart failure, suggesting that the intensity of the inflammatory response increases the risk of mechanical consequences and complications of ischemic injury and therefore may play a role in the development of heart failure. Increased concentrations of CRP may then help to identify patients at risk of developing congestive heart failure after ACS and prompt closer surveillance and more aggressive therapy and perhaps novel therapy aimed at prevention of adverse remodeling. Assessment of CRP on admission provides independent prognostic information and thereby improves the ability to identify those patients at highest risk of death and heart failure.[31]

A study by Mach et al. showed that among patients with acute ischemic heart disease and no biological markers of myocardial necrosis, the CRP concentration at the time of admission was significantly higher in patients in whom an acute myocardial infarction was ultimately diagnosed, while in patients with unstable angina the CRP levels were low.[31]

In the present study, the 90-day follow up shows that the Groups-2 and 3 had greater number of complications compared to Group-1. The mortality was only 2 % in Group-1 compared to 9% and 12% in Groups-2 and 3, respectively. The overall incidence of a major coronary event was 87% in patients with abnormal CRP vs 13% in patients with a normal CRP.

Liuzzo et al.[10] demonstrated that CRP elevation in patients with unstable angina, without evidence of myocardial damage as assessed with troponin T, is associated with poor outcome. In another study, Liuzzo et al., showed that severe myocardial ischemia in patients with variant angina without atherosclerotic coronary artery disease does not by itself induce an increase in plasma CRP.[32] Therefore, it is likely that CRP elevations are due to activation of inflammation. It has been shown that other pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6, interleukin-8 and TNF-a are elevated on admission in patients with acute coronary syndromes[33–35] and that these elevations may be associated with a worse outcome.[33]

It has been shown that CRP stimulates production of tissue factor by mononuclear cells, the main initiator of blood coagulation.[36] In addition, it has been suggested that CRP together with phospholipase A2 may cause complement activation and promote phagocytosis of damaged cells by activated neutrophils.[37] Therefore, it is conceivable that an elevated CRP signifies ongoing activation of inflammation that characterizes unstable coronary artery disease and indeed may be one of the causal factors of instability.

CRP levels were higher in patients with acute coronary syndromes as compared to the control group. However, it could not be ruled out that whether the observed difference would reach a significant level if a significantly larger sample size is used.

The study was not designed to study the correlation between CRP elevation and the rise in troponin T levels and their combined and independent effects on the coronary events in the follow-up.

CONCLUSIONS

The measurement of CRP at the time of admission in patients with suspected coronary artery disease may be helpful in identifying a group of patients who may be at high risk of cardiac complications and these patients need aggressive cardiac management and close monitoring after discharge.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are very thankful to Dr N. Rehan for his assistance and support in the statistical analysis of the study. We are grateful to the Department of Cardiology, Bolan Medical College Complex Quetta for their support and help. We would like to thank all the doctors, nurses, paramedical staff and the medical students who were linked, directly or indirectly, with this study for their support and input.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cannon CP, Braunwald E. Unstable angina and Non – ST elevation myocardial infarction. In: Kasper Dl, Fanci AS, Longo DL, Braunwald E, Hauser SL, Janeson JL., editors. Harrison's Principal of Internal Medicine. 16th ed. Newyork: MC Graw Hill; 2005. pp. 1301–494. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wallentin L The RISC group. Risk of myocardial infarction and death during treatment with low dose aspirin and intravenous heparin in men with unstable coronary artery disease. Lancet. 1990;336:827–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Theroux P, Waters D, Qui S, McCans J, de Guise P, Juneau M. Aspirin versus heparin to prevent myocardial infarction during the acute phase of unstable angina. Circulation. 1993;88:2045–8. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.5.2045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braunwald E TIMI IIIB investigators. Effects of tissue plasminogen activator and a comparison of early invasive and conservative strategies in unstable angina and non- Q-wave myocardial infarction.Results of the TIMI IIIB trial. Circulation. 1994;89:1545–56. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.89.4.1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fuster V, Badimon L, Badimon J, Chesebro JH. The pathogenesis of coronary artery disease and the acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:242–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199201233260406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ross R. Atherosclerosis- an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:115–26. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901143400207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harris TB, Ferruci L, Tracy RP, Corti MC, Wacholder S, Ettinger WH, Jr, et al. Association of elevated interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein levels with mortality in elderly. Am J Med. 1999;106:506–12. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00066-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beck B, Weintraub WS, Alexander R. Elevation of C-reactive protein in “active” coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 1990;65:168–72. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(90)90079-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Beer FC, Hind CR, Fox KM, Allan RM, Maseri A, Pepys MB. Measurement of serum C-reactive protein concentration in myocardial ischemia and infarction. Br Heart J. 1982;47:239–43. doi: 10.1136/hrt.47.3.239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liuzzo G, Biasucci LM, Gallimore JR, Grillo RL, Rebuzzi AG, Pepys MB, et al. The prognostic value of C-reactive protein and serum amyloid A protein in severe unstable angina. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:417–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199408183310701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ridker PM, Hennekens CH, Buring JE, Rifai N. C-reactive protein and other markers of inflammation in the prediction of cardiovascular disease in women. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:836–43. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003233421202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ridker PM, Rifai N, Clearfield M, Downs JR, Weis SE, Miles JS, et al. Air Force/Texas Coronary Atherosclerosis Prevention Study Investigators. Measurement of C-reactive protein for the targeting of statin therapy in the primary prevention of acute coronary events. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1959–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200106283442601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ridker PM, Glynn RJ, Hennekens CH. C-reactive protein adds to the predictive value of total and HDL cholesterol in determining risk of first myocardial infarction. Circulation. 1998;97:2007–11. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.20.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chew DP, Bhatt DL, Robbins MA, Penn MS, Schneider JP, Lauer MS, et al. Incremental prognostic value of elevated baseline C-reactive protein among established markers of risk in percutaneous coronary intervention. Circulation. 2001;104:992–7. doi: 10.1161/hc3401.095074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heeschen C, Hamm CW, Bruemmer J, Simoons ML. Predictive value of C-reactive protein and troponin T in patients with unstable angina: A comparative analysis. CAPTURE Investigators. Chimeric c7E3 Antiplatelet Therapy in Unstable angina Refractory to standard treatment trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:1535–42. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(00)00581-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindahl B, Toss H, Siebahn A, Venge P, Wallentin L. Markers of myocardial damage and inflammation in relation to long-term mortality in unstable coronary artery disease. FRISC Study Group. Fragmin during Instability in Coronary Artery Disease. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1139–47. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200010193431602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Biasucci LM, Liuzzo G, Grillo RL, Caligiuri G, Rebuzzi AG, Buffon A, et al. Elevated levels of C-reactive protein at discharge in patients with unstable angina predict recurrent instability. Circulation. 1999;99:855–60. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.7.855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Winter RJ, Bholasingh R, Lijmer JG, Koster RW, Gorgels JP, Schouten Y, et al. Independent prognostic value of C-reactive protein and troponin I in patients with unstable angina or non-Q-wave myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res. 1999;42:240–5. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuller LH, Tracy RP, Shaten J, Meilahn EN. Relation of C-reactive protein and coronary heart disease in the MRFIT nested case-control study.Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;144:537–47. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Katus HA, Looser S, Hallermayer K, Remppis A, Scheffold T, Borgya A, et al. Development and in vitro characterization of a new immunoassay of cardiac troponin T. Clin Chem. 1992;38:386–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Le J, Vilcek J. Interleukin 6: A multifunctional cytokine regulating immune reactions and the acute phase protein response. Lab Invest. 1989;61:588–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ledue TB, Weiner DL, Sipe JD, Poulin SE, Collins MF, Rifai N. Analytical evaluation of particle-enhanced immunonephelometric assays for C-reactive protein, serum amyloid A and mannose-binding protein in human serum. Ann Clin Biochem. 1998;35:745–53. doi: 10.1177/000456329803500607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Proposal for the multinational monitoring of trends and determinants in cardiovascular disease. Geneva: Cardiovascular Disease Unit of WHO; 1981. World Health Organization criteria for the diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cavusoglu Y, Gorenek B, Alpsoy S, Unalir A, Ata N, Timuralp B. Evaluation of C-reactive protein, fibrinogen and anti-thrombin III as risk factors for coronary artery disease. Isr Med Assoc J. 2001;3:36–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tomoda H, Aoki N. Prognostic value of C-reactive protein levels within six hours after the onset of acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2000;140:324–8. doi: 10.1067/mhj.2000.108244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.James SK, Armstrong P, Barnathan E, Califf R, Lindahl B, Siegbahn A, et al. GUSTO-IV-ACS Investigators. Troponin and C-reactive protein have different relations to subsequent mortality and myocardial infarction after acute coronary syndrome: A GUSTO IV substudy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:916–24. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)02969-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vasan RS, Sullivan LM, Roubenoff R, Dinarello CA, Harris T, Benjamin EJ, et al. Framingham Heart Study. Inflammatory markers and risk of heart failure in elderly subjects without prior myocardial infarction: The Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2003;107:1486–91. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000057810.48709.f6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mega JL, Morrow DA, De Lemos JA, Sabatine MS, Murphy SA, Rifai N, et al. B-type natriuretic peptide at presentation and prognosis in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: An ENTIRE-TIMI-23 substudy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;44:335–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sabatine MS, Morrow DA, de Lemos JA, Gibson CM, Murphy SA, Rifai N, et al. Multimarker approach to risk stratification in non-ST elevation acute coronary syndromes: Simultaneous assessment of troponin I, C-reactive protein, and B-type natriuretic peptide. Circulation. 2002;105:1760–3. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000015464.18023.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Varo N, de Lemos JA, Libby P, Morrow DA, Murphy SA, Nuzzo R, et al. Soluble CD40L: Risk prediction after acute coronary syndromes. Circulation. 2003;108:1049–52. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000088521.04017.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mach F, Lovies C, Gaspoz JM, Unger PF, Bouilli M, Urban P, et al. C-reactive protein as a marker for acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 1997;18:897–902. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a015198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liuzzo G, Biasucci LM, Rebuzzi AG, Gallimore JR, Caligiuri G, Lanza GA, et al. Plasma protein acute phase response in unstable angina is not induced by ischemic injury. Circulation. 1996;94:2372–80. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.10.2373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Biasucci LM, Vitelli A, Liuzzo G, Altamura S, Caligiuri G, Monaco C, et al. Elevated levels of interleukin-6 in unstable angina. Circulation. 1996;94:874–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.94.5.874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kanda T, Hirao Y, Oshima S, Yuasa K, Taniguchi K, Nagai R, et al. Interleukin-8 as a sensitive marker of unstable coronary artery disease. Am J Cardiol. 1996;77:303–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(97)89400-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Maury CPJJ, Teppo AM. Circulating tumor necrosis factor-alpha (cachectin) in myocardial infarction. J Int Med. 1989;225:333–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1989.tb00090.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cermak J, Key NS, Bach RR, Balla J, Jacob HS, Vercelotti GM. C-reactive protein induces human peripheral blood monocytes to synthesize tissue factor. Blood. 1993;82:513–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hack CE, Wolbink GJ, Schalkwijk C, Speijer H, Hermens WT, van den Bosch H. A role for secondary phospholipase A2 and C-reactive protein in the removal of injured cells.[Review] Immunol Today. 1997;18:111–5. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)01002-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]