Abstract

Background & objectives:

Stabilized live attenuated oral polio vaccine (OPV) is used to immunize children up to the age of five years to prevent poliomyelitis. It is strongly advised that the cold-chain should be maintained until the vaccine is administered. It is assumed, that vaccine vial monitors (VVMs) are reliable at all temperatures. VVMs are tested at 37°C and it is assumed that the labels reach discard point before vaccine potency drops to >0.6 log10. This study was undertaken to see if VVMs were reliable when exposed to high temperatures as can occur in field conditions in India.

Methods:

Vaccine vials with VVMs were incubated (10 vials for each temperature) in an incubator at different temperatures at 37, 41, 45 and 49.5°C. Time-lapse photographs of the VVMs on vials were taken hourly to look for their discard-point.

Results:

At 37 and 41°C the VVMs worked well. At 45°C, vaccine potency is known to drop to the discard level within 14 h whereas the VVM discard point was reached at 16 h. At 49.5°C the VVMs reached discard point at 9 h when these should have reached it at 3 h.

Conclusion:

Absolute reliance cannot be placed on VVM in situation where environmental temperatures are high. Caution is needed when using ‘outside the cold chain’ (OCC) protocols.

Keywords: Cold chain, oral polio vaccine, vaccine potency, vaccine vial monitors

Poliomyelitis is a disease caused by poliovirus. Stabilized live attenuated oral polio vaccine (OPV) is used to immunize children up to the age of five years. The vaccine being highly thermo-labile needs a stringently monitored cold-chain. All the vials of OPV have a temperature sensitive label, the vaccine vial monitor (VVM), attached at the time of manufacture, to prominently display the cumulative exposure to heat. It is a standard practice to discard vials when VVM colour changes to grey from white suggesting that the potency of the vaccine has dropped to >0.6 log101.

It is strongly advised that the cold-chain should be maintained until the vaccine is administered. In a recent study2 reliance on VVMs was recommended to achieve less wastage. There was greater user-preference for carrying vaccines without cold packs on national immunization days (NIDs).

It is assumed, that VVMs are completely reliable at all temperatures. Routinely, VVMs are tested in an accelerated degradation test at 37°C3,4. The heat sensitive polymers in the label change colour and it represents the cumulative exposure to heat. When vaccine potency has dropped to >0.6 log10 (vaccine unlikely to provide protection), the VVM inner square becomes darker than the outer reference ring (vial discard-point)4. It has been proven repeatedly that the monitors work well at 37°C and the labels reach discard point well before vaccine potency drops to >0.6 log101.

However, it is not necessarily true that because vaccine virus degeneration matches colour changes on the VVM at 37°C, this will hold true at other temperatures. At higher temperatures virus may degenerate faster than the heat sensitive polymer. We carried out this study based on the known degradation rate of vaccine virus; to see if VVMs were reliable when exposed to higher temperatures as can occur in field conditions in India. In India, in the northern States of Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Rajasthan, summer temperatures rise to 45°C routinely and sometimes go as high as 50°C5,6. The half life of polio vaccine virus is 48 to 72 h at 37°C, 24 h at 41°C, 14 h at 45°C and 3 h at 50°C7.

Material & Methods

The study was conducted in National Institute of Immunology, New Delhi in January 2010. For this study the VVMs on OPV bottles used for routine immunization in India were used. The bottles were kept in the deep freezer at -20°C. The vials were incubated in a lighted dry-incubator (Galaxy 48S made by New Brunswick, UK) at different temperatures. The tests were performed at 37, 41, 45 and 49.5°C. Ten vials were used for each test-run for convenience in calculations, in terms of percentages. Time-lapse photographs of the VVMs were taken hourly, using a Nikon D70s camera (Nikon D70s, Thailand) controlled by a PC through the Camera Control Pro 2 software (version 2.5.0, Japan). The digital images were examined to look for the time at which VVMs reached their discard-point. Two investigators (AS and NG) independently examined the digital images for the discard point and the difference of opinion (<5% cases) was resolved with the help of another investigator (JP).

Results & Discussion

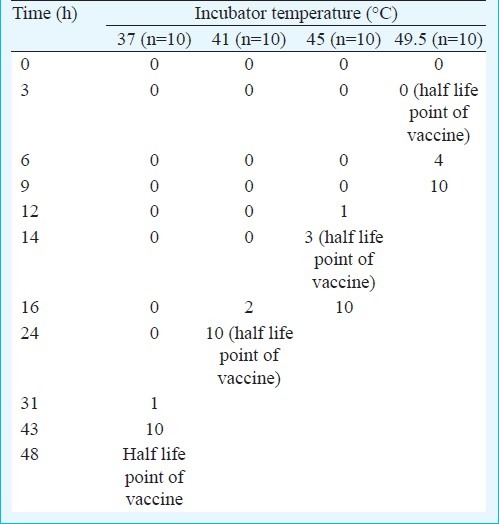

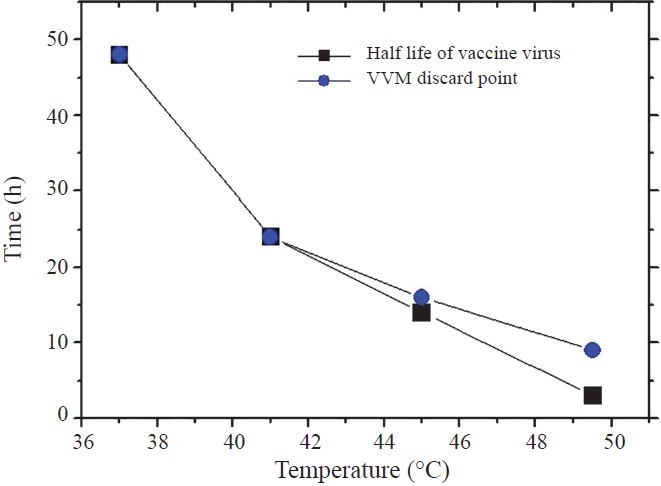

At 37°C all 10 vials reached discard point within 43 h (well before 48 h when the vaccine potency deteriorates to a level that the vaccine is useless). At 41°C the vials reached discard point within 24 h. Here again the VVMs worked well. However at 45°C, only three vials reached discard point at 14 h. At 49.5°C no bottle reached discard point at 3 h which was the half life point of vaccine. Only 40 per cent vials reached discard point at 6 h, all 10 vials reached discard point only after 9 h (Table). The Fig. shows the disparity between virus viability and the discard point of the VVMs.

Table.

Number of vials with VVMs reaching discard stage at various time points when incubated at different temperatures

Fig.

Half life of vaccine virus compared to the discard point of vaccine vial monitors. Each point represents the time at which all bottles reach discard point

Conventionally, VVMs were used within the cold chain where the vaccine is stored at temperatures below 8°C. Field workers are trained to place reliance on VVMs8. Experiments using the VVMs outside the cold chain were done by Halm and colleagues2. They used 20 dose vials, and at the end of the day, unopened vials were returned to cold storage for use on the following day, and so on, till the VVM reached discard point. They found that no vials reached discard point and needed to be thrown away unused, when this protocol was utilized. On the other hand, in the control group, three vials carried in ice-lined vaccine-carriers had to be disposed of, because the labels got wet and detached from their bottles. The ambient temperatures went up to 40°C during the study. Over 90 per cent supervisors and vaccinators preferred NIDs without ice packs and this will soon become the standard practice2. There is support for this form of innovation9.

This study was done in the context of the temperatures in the states of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar in India where polio has been difficult to control and where summer temperatures rise to 45°C routinely and sometimes go as high as 50°C5. Our findings suggest that the VVMs are not reliable when exposed to high environmental temperatures. Previous studies have shown deterioration in virus levels resulting from thaw-freeze cycles which are not indicated by the VVMs1. This makes the practice of returning vials exposed to ambient temperatures, to the freezer for storage at night and reuse later, particularly risky.

The main shortcoming of our study was that we did not test for vaccine potency but depended on literature for determining the half life of the virus strain at different temperatures. It was not considered crucial because VVMs are not specific to any one strain of polio virus but generic to all polio viruses. Studies recommend looking at total virus load although specific virus, with differing heat labiality, may have different rates of degradation4. Under such circumstances, immunization against one strain may be ineffective although the total number of virus would be higher than the number required for passing the test of potency.

The WHO recommends VVMs to be sealed in a plastic cover and tested in a water bath at 37°C8. In the present study incubator was used as this was more likely to mimic conditions in the field.

In conclusion, absolute reliance cannot be placed on VVM in situation where environmental temperatures are high. Caution is recommended when using ‘outside the cold chain’ (OCC) protocols.

References

- 1.Chand T, Sahu AK, Saha K, Singh V, Meena J, Singh S. Stability of oral polio vaccine at different temperatures and its correlation with vaccine vial monitors. Curr Sci. 2008;94:172–5. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Halm A, Yalcouye I, Kamissoko M, Keita T, Modjirom N, Zipursky S, et al. Using oral polio vaccine beyond the cold chain: a feasibility study conducted during the national immunization campaign in Mali. Vaccine. 2010;28:3467–72. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.02.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO. Manual of Laboratory methods for testing of vaccines used in the WHO Expanded Programme on Immunization (WHO/VSQ/97.04). WHO [WHO/VSQ/97.04] WHO. Geneva Ref Type: Electronic Citation. 1997. [accessed on March 20, 2012]. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/1997/WHO_VSQ_97.04_%28parts1-2%29.pdf .

- 4.WHO. Testing the correlation between vaccine vial monitor and vaccine potency (WHO/V&B/99.11). WHO. WHO. Geneva Ref Type: Electronic Citation. 1999. [accessed on March 20, 2012]. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/1999/WHO_V&B_99.11.pdf .

- 5.SAARC. SAARC disaster management center New Delhi South Asia Disaster Report 2007. SAARC. 2010. New Delhi Ref Type: Electronic Citation. 2010. Jul 7, [accessed on March 20, 2012]. http://saarcsdmc.nic.in/pdf/publications/sdr/chapter-7.pdf .

- 6.Wikipedia. Geography of Uttar Pradesh. Wikipedia. Florida Ref Type: Electronic Citation. 2010. [accessed on March 20, 2012]. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geography_of_Uttar_Pradesh .

- 7.WHO. Temperature sensitivity of vaccines (WHO/IVB/06.10). WHO Geneva. WHO. Ref Type: Electronic Citation. 2006. [accessed on March 20, 2012]. Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2006/WHO_IVB_06.10_eng.pdf .

- 8.WHO. World Health Organization Vaccine vial monitor Training guidelines (WHO/EPI/LHIS/96.04). WHO. WHO. 1996. WHO. Geneva Ref Type: Electronic Citation. 1990. [accessed on March 20, 2012]. http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/1996/WHO_EPI_LHIS_96.04_eng.pdf .

- 9.WHO. Making use of Vaccine Vial Monitors Flexible vaccine management for polio (WHO/V&B/00.14). WHO. WHO. Geneva Ref Type: Electronic Citation. 2004. [accessed on March 20, 2012]. Available from: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2000/WHO_V&B_00.14.pdf .