Abstract

Background:

Resection of eyelid malignancies leads to complex reconstructive problems due to the functional and aesthetic importance of an eyelid. Hence, a large number of such cases are referred to plastic surgery facilities. Eyelid malignancies are of varied histological types and the western and Asian data have considerable variations in case distribution and presentation. This study is an attempt to characterise these tumours in the Indian population.

Materials and Methods:

The present study is a retrospective analysis of 85 consecutive cases of eyelid malignancies that reported to a tertiary health care facility in central India over a 15-year period starting from January 1996 up to December 2009. The cases were analysed for their age of presentation, sex distribution, tumour location, delay in seeking treatment, recurrence rate and variations with respect to the pathological subtype.

Observations:

Mean age of presentation for all the malignancies was 59 years. The median age of presentation was 65 years for basal call carcinoma (BCC), 58 years for sebaceous gland carcinoma (SGC), 55 years for squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and 45 years for malignant melanoma. There was slight female preponderance as 56.28% of the patients were females. The most common location of the tumour was lower lid (58.2%) for all the malignancies. BCC was the most common malignancy (48.2%) followed by SGC (31.2%) and SCC (13.7%). Mean duration of symptoms was 9 months (range 3-21 months). The most common presenting complaint was mass with ulceration across all histological subtypes. Other associated complaints included itching, discharge from eye, pain and ptosis. The mean size of tumour at diagnosis was 2.34 ± 0.4 cm for BCC, 2.19 ± 0.6 cm for SGC and 1.99 ± 0.7 cm for SCC. The mean rate of growth of BCC was 1.39 cm/year. The corresponding values for SGC and SCC were 3.63 and 4.89 cm/year, respectively. The rate of follow-up was 89% at 3 months, 71% at 6 months, 62% at 1 year and 31% at 5 years. Recurrence rate was 1.9% for BCC and 12.7% for SGC. Surgical methods used included wedge excision and primary closure, excision and skin grafting, and tarso-conjunctival flap.

Conclusions:

We recommend that the surgeons treating eyelid malignancies in India should have a high index of suspicion for SGC. A wider margin of 10 mm is recommended for SGC excision as opposed to 5 mm for BCC.

KEY WORDS: Basal cell carcinoma India, eyelid, malignancy, sebaceous gland carcinoma

INTRODUCTION

The incidence of eyelid swellings appears to be increasing.[1–5] Complex reconstructive problems associated with the loss of an eyelid mean that a large number of such cases are referred to plastic surgery facilities. However, limited data are available, and hence the eyelid malignancies remain largely uncharacterized. Data of ocular adnexal malignancies in a particular geographical region have been shown to serve as a reference for that particular region for future research and help in guiding physicians and policy makers in planning resources for screening, treatment, and prevention of malignancy of the eye and ocular adnexa.[6]

Eyelid malignancies have a varied pathology including basal cell carcinoma (BCC), squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), malignant melanoma (MM), sebaceous gland carcinoma (SGC) and other rare tumours like hemangiopericytoma (HMP). The western and Asian data have considerable variations in case distribution and presentation. This study is an attempt to characterise these tumours in the Indian population.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The present study is a retrospective analysis of 85 consecutive cases of eyelid malignancies that reported to the Department of Plastic and Maxillofacial Surgery at a tertiary health care facility in central India. We included cases that reported to the study center over a 15-year period starting from January 1996 up to December 2009. In each case, the clinical diagnosis of eyelid malignancy was confirmed preoperatively by fine needle aspiration cytology or histopathology. The cases were treated with wide local excision with a 5-10 mm margin of normal tissue and an appropriate combination of split skin grafts (SSG), tarso-conjunctival flaps (TCF) and Mustarde's flaps (MF). The cases were analysed for their age of presentation, sex distribution, tumour location, delay in seeking treatment, recurrence rate and variations with respect to the pathological subtype.

RESULTS

Age

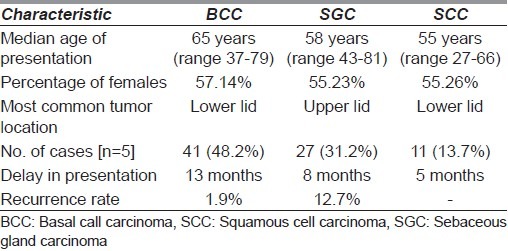

The mean age of presentation in our study was 59 years (range 27-81; SD 19.7). In the present study, the median age of presentation was 65 years (range 37-79) for BCC, 58 years (range 43-81) for SGC, 55 years (range 27-66) for SCC and 45 years (range 31-56) for MM. The only case of rhabdomyosarcoma presented to us at 12 years of age [Table 1].

Table 1.

Comparison of BCC, SGC and SCC

Sex

There was slight female preponderance as 56.28% of the patients were females. Females were more common in all the pathological subtypes as 57.14% of the patients with BCC, 55.23% of SGC and 55.26% of SCC were females [Table 1].

Tumour location

The most common location of the tumour was lower lid (58.2%) for all the malignancies. The lower lid was also the most common site for tumour location for all histological subtypes except SGC (59% upper lid vs. 41% lower lid [Table 1].

Clinical presentation

The most common presenting complaint was mass with ulceration across all histological subtypes. Twenty-one patients of BCC (51.2%), 15 patients of SGC (55.5%) and 6 patients of SCC (55.5%) presented with mass and overlying ulceration. Mass alone was the presenting complaint in 13 patients of BCC (31.7%), 9 patients of SGC (33.3%) and 3 patients of SCC (27.3%). Ulcer alone was present in 7 patients of BCC (17.1%), 3 patients of SGC (11.1%) and 2 patients of SCC (18.2%). Other associated complaints included itching, discharge from eye, pain and ptosis [Table 1].

Tumour size

The mean size of tumour at diagnosis was 2.34 ± 0.4 cm for BCC, 2.19 ± 0.6 cm for SGC and 1.99 ± 0.7 cm for SCC [Table 1].

Rate of tumour growth

The mean rate of growth of BCC was 1.39 cm/year. The corresponding values for SGC and SCC were 3.63 and 4.89 cm/year, respectively [Table 1]

Pathology

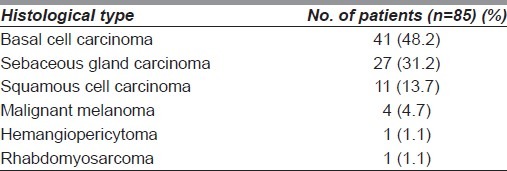

BCC was the most common malignancy (48.2%) followed by SGC (31.2%) and SCC (13.7%). There were four cases of MM and one case each of rhabdomyosarcoma, HMP and schwannoma [Table 2].

Table 2.

Distribution of eyelid malignancies

Delay in presentation

Mean delay in presentation was 9 months (range 3-21 months). Mean delay in presentation for BCC was 13 months, while the delay was 8 months for SGC and 5 months for SCC [Table 1].

Follow-up and recurrence

Patients were followed up at 3 months, 6 months, 1 year and then yearly till 5 years. The rate of follow-up was 89% at 3 months, 71% at 6 months 62% at 1 year and 31% at 5 years. Recurrence rate was 1.9% for BCC and 12.7% for SGC [Table 1].

DISCUSSION

Eyelid tumours are commonly encountered in plastic surgery practice. Malignancies requiring resection with a wide margin often pose challenging reconstructive problems to the treating surgeon. Eyelid malignancies can be of varied histological types. These malignancies tend to behave differently in terms of presentation, progression and response to surgical resection. Treating eyelid malignancies as a single entity without accurate clinical and histological diagnosis is fraught with the danger of over simplification. The present study aims to characterise these eyelid malignancies by encompassing 15 years of data in an attempt to provide guidelines for assessment of the tumours.

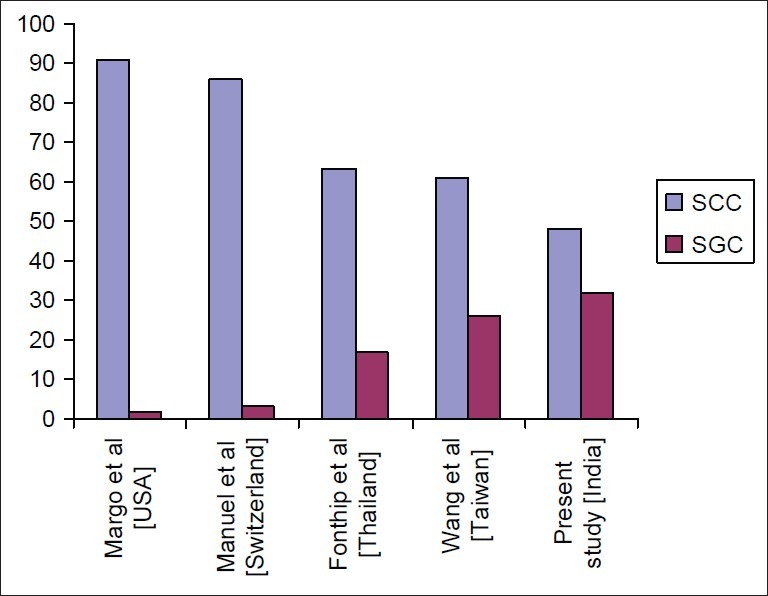

BCC is largely recognised as the most common eyelid malignancy worldwide. However, the relative incidence of BCC shows large regional variation. Data reported from the United States of America show that nearly 90% of eyelid malignancies are BCC.[7,8] Studies suggest that in Caucasians, BCC constitutes about 80-90% of the malignant eyelid tumours.[9] BCC was the most frequent malignant tumour (86%), followed by SCC (7%) and sebaceous carcinoma (3%) in Switzerland.[10] There is a definite decrease in the proportion of eyelid malignancies diagnosed as BCC as we move towards the equatorial region. Asian countries have consistently reported a relatively lower incidence of BCC, though it still remains the most common eyelid malignancy. Lin Hsin-Yi et al. found that in Taiwan, BCC was the most common eyelid malignancy, but it accounted for only 65.1% of the cases.[11] Similarly, Wang et al. reported an incidence of 62.2% in another study done in Taiwan.[5] In Thailand, BCC constitutes 64% of all eyelid tumours.[6] The only exception to this trend of lower incidence of BCC in Asian countries is the study done by Sao-Bing Lee et al. in Singapore, who have reported 84% incidence of BCC.[12] In the present study, BCC constituted 48.2% of all malignancies. This is lower than the incidence reported by other Asian countries and is significantly less than the data reported by the western studies [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Comparison of incidence of BCC and SGC showing increasing incidence of SGC and decreasing incidence of BCC in Asian countries

SGC is rare among Whites, accounting for 1-5.5% of all eyelid malignancies, which is far behind BCC and SCC.[13–15] In Asian countries, there is a greater incidence of SGC. Chinese studies have reported an incidence of 7-24%.[5,11] An incidence of 10-40% has been reported from Singapore, Thailand and Japan.[9,12,16] In the present study, SGC constituted 31.2% of all cases. It remains to be seen whether this increased rate of SGC is due to increase in incidence of SGC per se or due to a relative decrease in the incidence of BCC. Large population-based studies are required to establish the trend, but racial, genetic and geographical factors all seem to play a role[5,9] [Figure 1].

The mean age of presentation in our study was 59 years (range 27-81; SD 19.7). One patient of rhabdomyosarcoma was excluded from calculation of the mean age as only this case was seen in childhood. The mean age in the present study correlates well with that reported in other studies from Asia. The median age at diagnosis in Singapore was reported to be 63 years in males and 66 years in females.[12] Lin Hsin-Yi et al. reported that the mean age at diagnosis of eyelid cancers was 62.6 ± 14.1 years in Taiwan.[11] Fonthip Na Pombejara et al. reported a rather earlier mean age of presentation [52.4 years (SD 21.8)] in Thailand.[16] A slightly later age of presentation of 72.0 ± 12.4 years has been reported by Takamura Hiroshi from Japan.[9] In the present study, the median age of presentation was 65 years (range 37-79) for BCC, 58 years (range 43-81) for sebaceous cell carcinoma, 55 years (range 27-66) for SCC and 45 years (range 31-56) for MM. The only case of rhabdomyosarcoma presented to us at 12 years of age. Wang et al. have reported that in Taiwan, the mean age of presentation was 61.8 years (range 10-86) for BCC and 68.1 years (range 48-91) for SGC.[5]

In the present study, there was slight female preponderance as 56.28% of the patients were females. Females were more common in all the pathological subtypes; 57.14% of the patients with BCC, 55.23% of SGC and 55.26% of SCC were women. There seems to be large variations in the sex ratio as depicted by other studies. Wang et al. reported that though the incidence of lid malignancies was more in women than men (54.3% vs. 45.7%), there was a slight predominance of BCC in men (43 males, 36 females). Women greatly outnumbered men in SGC (21 females, 9 males).[5] Fonthip et al. found that most of the patients with eyelid tumours in their study were males.[16] Sihota et al. found that the sex distribution was equal for both sebaceous cell carcinoma and BCC, but males were relatively more often affected with SCC (60%).[17] It is possible that the variable sex incidence is due to the variations in the cohort of patients under study.

The most common location of the tumour was lower lid (58.2%) for all the malignancies. The lower lid was also the most common site for tumour location for all histological subtypes except SGC (59% upper lid). This result was the same as that of previous studies. The predominance of BCC in the lower eyelid has been shown in various studies. However, more SGC occurs in the upper eyelid due to greater number of meibomian glands in the upper lid.[5]

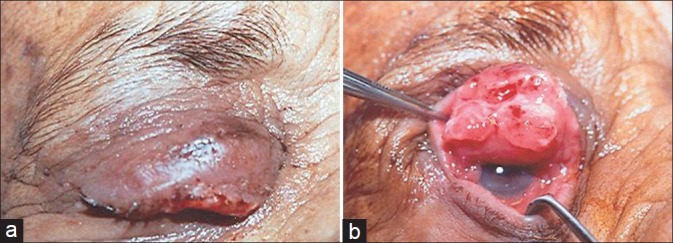

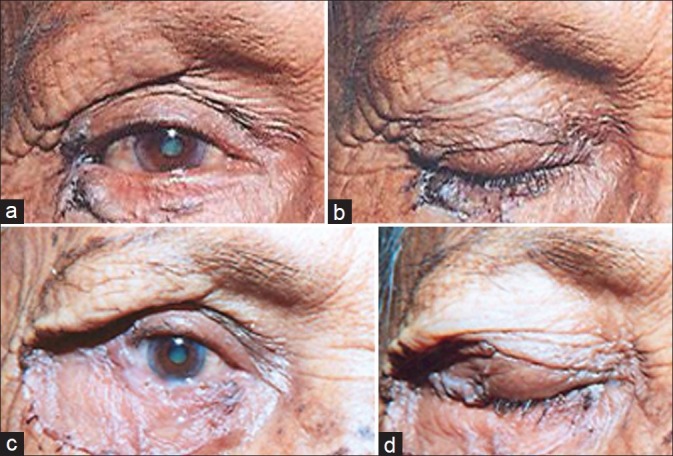

The most common presenting complaint was mass with ulceration across all histological subtypes. Twenty-one patients of BCC (51.2%), 15 patients of SGC (55.5%) and 6 patients of SCC (55.5%) presented with mass and overlying ulceration. One patient of SCC had an ulcer present on the conjunctival side with an overlying mass [Figure 2a and b]. Mass alone was the presenting complaint in 13 patients of BCC (31.7%), 9 patients of SGC (33.3%) and 3 patients of SCC (27.3%). Ulcer alone was present in 7 patients of BCC (17.1%), 3 patients of SGC (11.1%) and 2 patients of SCC (18.2%). Other associated complaints included itching, discharge from eye, pain and ptosis. Two cases of BCC had an underlying hyperpigmented lesion of longstanding duration, which had undergone malignant change. Two patients of SGC had history of recurrent chalazion. The patient in Figure 3a and b had history of recurrent chalazion. The lesion was excised with a margin of only 1 mm based on the preoperative suspicion. However, the histology was suggestive of SGC with clear margins. The patient is recurrence free after 3 years of follow-up.

Figure 2.

(a) Squamous cell carcinoma of upper lid; (b) same patient as in a showing ulceration on the conjunctival surface

Figure 3.

(a) Sebaceous gland carcinoma of lower lid. Patient had history of six documented episodes of recurrent chalazion. (b) Same patient as in a treated with wedge excision and primary closure

There was no difference between the various histological subtypes in terms of size of tumour. The mean size of tumour at diagnosis was 2.34 ± 0.4 cm for BCC, 2.19 ± 0.6 cm for SGC and 1.99 ± 0.7 cm for SCC. However, statistically significant difference was observed in the rate of growth of tumour. The rate of tumour growth was estimated by dividing the size of the tumour at the time of diagnosis by the duration of symptoms.[18] The mean rate of growth of BCC was 1.39 cm/year. The corresponding values for SGC and SCC were 3.63 and 4.89 cm/year, respectively. We observed that the rate of tumour growth was strongly associated with the type of malignancy (Kruskal-Wallis test; P=0.001). BCC was the slowest growing tumour and SCC the fastest. SGC had an intermediate rate of growth. Mean duration of symptoms for all histological subtypes was 9 months (range 3-21 months). Average duration of symptoms for BCC was 13 months, while the duration was 8 months for SGC and 5 months for SCC. This is probably due to a more rapid rate of growth of SCC as opposed to SGC and BCC.

It stems from the above discussion that the clinical symptoms of eyelid malignancies closely resemble each other. Higher rate of tumour growth points to a more aggressive malignancy like SCC. SGC, however, presents a more confusing picture as its rate of growth and progression is intermediate between that of BCC and SCC. BCC and SGC also behave differently in their response to treatment and postoperative course. Mortality from eyelid and medial canthal BCC ranges from 2 to 11%.[8] On the other hand, SGC is traditionally considered among the most lethal of all tumours of the ocular adnexa. Mortality from SGC has been estimated to be from 6 to 30% in a previous study.[15] According to the literature, distant metastasis affects 14-25% of the cases and involves lymph node or haematogenous spread into liver, lungs, brain and bones.[19–21] Thus, it is imperative that accurate diagnosis should be made as early as possible. In the present study, three patients (two SGC and one SCC) presented with multiple distant metastases.

Patients were followed up at 3 months, 6 months, 1 year and then yearly till 5 years to detect any evidence of recurrence. The rate of follow-up was 89% at 3 months, 71% at 6 months, 62% at 1 year and 31% at 5 years. The recurrence rate at the end of 5 years was 1.9% for BCC and 12.7% for SGC. In the previous studies of eyelid BCC, a recurrence rate of 5.36-6.1% was observed over 3 or 4 more years of follow-up.[19,20] Sebaceous carcinoma is reported to recur in 6-29% of the cases. The majority of all recurrences appear within the first 4 years after treatment.[21] The recurrence rate in the present study was lower than the rates reported in previous studies. However, due to relatively lower follow-up rate, no substantial claims can be made.

As a matter of departmental policy, eyelid malignancies were excised with a free margin of 5 mm till 2004. However, as the rate of recurrence for SGC was unacceptably high, the current policy is to excise all cases of SGC with a 10 mm margin. Retrospective analysis of our data indicates that the recurrence rate of SGC has gone down from 16.9% before 2004 to 6.9% after 2004. SCC is always excised with 8-10 mm margin at our institute. This greater margin leads to more extensive loss of eyelids. Our preferred mode of lid reconstruction is a TCF. Over the past 15 years, we have used the TCF successfully in 40 patients (11 BCC, 20 SGC and 9 SCC) [Figure 4a–f]. However, since 2004, more and more patients of SGC have been subjected to TCF. Wedge excision with primary closure of defect has been used in 22 patients (16 BCC, 4 SGC and 2 SCC) [Figures 3a, b, 5a and b]. Skin grafting alone has been deployed in 17 patients [14 BCC, 3 SGC] [Figures 6a–d]. It is evident that a greater free margin requires more complex reconstructive procedure. We recommend that SGC should be excised with a free margin of 10 mm. Reconstructive procedure can be a matter of surgeon's choice, but in our experience, TCF can be used for a satisfactory reconstruction.

Figure 4.

(a) Large fungating squamous cell carcinoma of upper lid; (b) large fungating SCC of upper lid; (c) excision defect showing complete loss of eyelid; (d) reconstruction using TCF; (e) postoperative result; (f) postoperative result showing adequate function

Figure 5.

(a) BCC near lateral canthus; (b) wedge excision and primary closure of patient in a Figure 5a

Figure 6.

(a) BCC of lower lid; (b) BCC of lower lid; (c) BCC treated with excision and split thickness graft; (d) same patient as in c showing adequate functional recovery

The present study shows a greater incidence of SGC and a relatively lower incidence of BCC in the Indian population though BCC is the most common histological type. The authors acknowledge the fact that the study has the limitation of low long-term follow-up (31% at 5 years). This also makes the computation of survival statistics difficult. However, a high occurrence rate of SGC is uniquely evident in India, requiring a high index of suspicion and aggressive treatment. Clinical features alone cannot be used successfully for diagnosis though a higher rate of growth suggests a more aggressive variant. We recommend that all eyelid malignancies should be subjected to preoperative histological diagnosis. BCC can be excised safely with a 5 mm margin, but a 10 mm margin for SGC and an 8-10 mm margin for SCC are recommended. Eyelid reconstruction can be done by an array of methods; however, we recommend the use of TCF.

CONCLUSION

We recommend that the surgeons treating eyelid malignancies in India should have a high index of suspicion for SGC. It is recommended that large population-based studies should be conducted to accurately quantify the incidence and prevalence of eyelid malignancies. Preoperative histological confirmation of diagnosis and a greater free margin for excision of SGC is recommended.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdi UN, Tyagi V, Maheshwari V, Gogi R, Tyagi SP. Tumors of eyelid: A clinicopathologic study. (416,418).J Indian Med Assoc. 1996;94:405–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abe MY, Ohnishi Y, Hara Y, Shinoda Y, Jingu K. Malignant tumor of the eyelid-Clinical survey during 22-year period. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 1983;27:175–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Al-Buloushi A, Filho JP, Cassie A, Arthurs B, Burnier MN., Jr Basal cell carcinoma of the eyelid in children: A report of three cases. Eye. 2005;19:1313–4. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6701758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shields JA, Demirci H, Marr BP, Eagle RC, Jr, Shields CL. Sebaceous carcinoma of the eyelids: Personal experience with 60 cases. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:2151–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2004.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang JK, Liao SL, Jou JR, Lai PC, Kao SC, Hou PK, et al. Malignant eyelid tumors in Taiwan. Eye. 2003;17:216–20. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6700231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pombejara FN, Tulvatana W, Pungpapong K. Malignant tumors of the eye and ocular adnexa in Thailand: A six-year review at King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital. Asian Biomed. 2009;3:551–5. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cook BE, Jr, Bartley GB. Epidemiologic characteristics and clinical course of patients with malignant eyelid tumors in an incidence cohort in Olmsted county, Minnesota. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:746–50. doi: 10.1016/S0161-6420(99)90161-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Margo CE, Waltz K. Basal cell carcinoma of the eyelid and periocular skin. Surv Ophthalmol. 1993;38:169–92. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(93)90100-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hiroshi T, Hidetoshi Y. Clinicopathological Analysis of Malignant Eyelid Tumor Cases at Yamagata University Hospital: Statistical Comparison of Tumor Incidence in Japan and in Other Countries. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2005;49:349–54. doi: 10.1007/s10384-005-0229-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deprez, Manuel, Uffer, Sylvie Clinicopathological Features of Eyelid Skin Tumors. A Retrospective Study of 5504 Cases and Review of Literature. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:256–62. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e3181961861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin HY, Cheng CY, Hsu WM, Kao WH, Chou P. Incidence of eyelid cancers in Taiwan: A 21-year review. Ophthalmology. 2006;113:2101–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee SB, Saw SM, Au Eong KG, Chan TK, Lee HP. Incidence of eyelid cancers in Singapore from 1968 to 1995. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999;83:595–7. doi: 10.1136/bjo.83.5.595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weiner JM, Henderson PN, Roche J. Metastatic eyelid carcinoma. Am J Ophthalmol. 1986;101:252–4. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(86)90609-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ni C, Searl SS, Kuo PK, Chu FR, Chong CS, Albert DM. Sebaceous cell carcinomas of the ocular adnexa. Int Ophthalmol Clin. 1982;22:23–61. doi: 10.1097/00004397-198202210-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kass LG, Hornblass A. Sebaceous carcinoma of the ocular adnexa. Surv Ophthalmol. 1989;33:477–90. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(89)90049-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pombejara FN, Tulvatana W, Pungpapong K. Malignant tumors of the eye and ocular adnexa in Thailand: A six-year review at King Chulalongkorn Memorial Hospital. Asian Biomed. 2009;3:551–5. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sihota R, Tandon K, Betharia SM, Arora R. Malignant Eyelid Tumors in an Indian Population. Arch Ophthalmol. 1996;114:108–9. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1996.01100130104031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jahagirdar SS, Thakre TP, Kale SM, Kulkarni H, Mamtani M. A clinicopathological study of eyelid malignancies from central India. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2007;55:109–12. doi: 10.4103/0301-4738.30703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pieh S, Kuchar A, Novak P, Kunstfeld R, Nagel G, Steinkogler FJ. Long term results after surgical basal cell carcinoma excision in the eyelid region. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999;83:85–8. doi: 10.1136/bjo.83.1.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Steinkogler FJ, Scholda CD. The necessity of long-term follow up after surgery for basal cell carcinomas of the eyelid. Ophthalmic Surg. 1993;24:755–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zürcher M, Hintschich CR, Garner A, Bunce C, Collin JR. Sebaceous carcinoma of the eyelid: A cliniopathological study. Br J Ophthalmol. 1998;82:1049–55. doi: 10.1136/bjo.82.9.1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]