Abstract

Background

Qeshm (26.75N, 55.82E), Iran, is 1500 km² island in the Strait of Hormuz. Qeshm is a free trade zone, acting as an important channel for international commerce, and has been the site of much recent development. There is potential risk of stinging ant attacks for residents and visitors that may occur in the island. The aims of this study were to find out the fauna, dispersion, and some of the biological features of ant species with special attention to those, which can play role on the public health of the island.

Methods:

In this cross-sectional study, we surveyed ants around the island using non-attractive pitfall traps and active collection to evaluate potential threats to humans and other species during 2006–2007. All collected specimens were identified using the morphological ant keys.

Results:

Only six ant species were found: Pachycondyla sennaarensis (41%), Polyrhachis lacteipennis (23%), Camponotus fellah (16%), Cataglyphis niger (9%), Tapinoma simrothi (7%), and Messor galla (4%).

Conclusion:

We were surprised not to find any cosmopolitan tramp ants so often associated with commerce and development. Instead, all six species may be native to the Middle Eastern region. The most common species, P. sennaarensis, has a powerful sting and appears to do well around human habitations. This species may prove to be a serious pest on the island.

Keywords: Pachycondyla sennaarensis, Public health, pests, African needle ant, Iran

Introduction

Ants (superfamily Formicoidea) have a worldwide distribution, some certain genera and species present in almost all countries and in all places. They are among the most successful insects which occurring everywhere in terrestrial habitats and outnumbering most of other terrestrial animals in individuals (Borrer et al. 1989, Taylor 2007).

Some ant species due to some certain characters such as their social organization are considered as the most successful invaders (Moller 1996, Williamson and Fitter 1996). Those ants that have principally spread throughout the world human trade are considered as tramp species which living in close association with man. They have a wide distribution in the world and can find them in many areas even out of their original ranges. They tend to have widespread geographical distributions, and share life history characteristics including queen number, nest structure, and foraging behaviour (McGlynn 1999). They share several characteristics as unicoloniality resulting in an absence of intraspecific aggression, polygyny (multiple queens nests), high interspecific aggression and the small size of workers (Passera 1994).

All ant species are grouped into a single family, the Formicidae, which includes 10–20 subfamilies (Astruc et al. 2004). Subfamily Ponerinae is one of the most known ones and comprises ten genera. The genus Pachycondyla [Smith (1858)], includes a large group of ants with about 200 described species, worldwide distribution, and mostly known from tropics and sub-tropics regions (Bolton 1995).

A few species have an obvious and functional sting, whereas other ants bite with their maxillae with no sting. The members of genus Pachycondyla have sting which use for their predatory activities. The majority species of the genus Pachycondyla are scavengers or predators of arthropods, the later subdue their pray with venom (Wild 2002, Orivel and Dejean 2001).

Some ant species capable of inciting hypersensitivity reactions include P. sennaarensis (Steen et al. 2005). There has also reported anaphylactic shock in humans following the stings form P. sennaarensis in the United Arab Emirates (Dib et al. 1995). This taxon is one of the eight genera of ants that have been associated with sting allergy worldwide.

Pachycondyla sennaarensis has been incriminated as an intermediate host for the poultry cestode, Raillietina tetragona in Sudan (Mohammed et al. 1988).

To date, occurrence of P. sennaarensis has been confirmed from southern parts of Iran (Tirgari et al. 2004, Tirgari and Paknia 2004, Tirgari and Paknia 2005, Akbarzadeh et al. 2006 a, b, Paknia 2006). However, there is little information on species composition, distribution, ecology, biology, behaviour and public health threat of stinging ants in Iran.

There are many public health concerns in Qeshm due to recent development of the island and increasing the population. Besides, there are many attractions, which make the island one of the most popular tourists’ destinations in the region. There is potential risk of stinging ant attacks for residents and visitors that may occur indoors or outdoors.

This study was conducted to identify ant species, dispersion, and some of their biological and morphological features to throw light on status of P. sennaarensis as a public health pest in the island. It tends to provide preliminary information on ants in Qeshm for further prevention and control programs.

Materials and Methods

Study Site

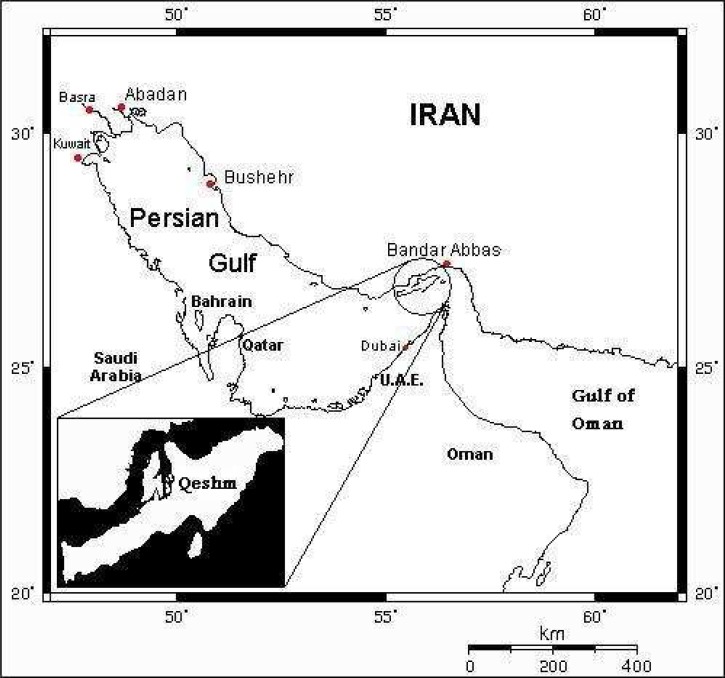

Qeshm is situated at the entrance of the Persian Gulf in the Strait of Hormoz, in the 55 to 57 degrees longitude and 25 to 27 degrees latitude. It is 1500 km² in area with 136 km as length and 11 km as average width. The island is 30 km long at its maximum width. The highest point of Qeshm, on a salt field to its west, is 397 meters from sea level with the average height of 10 meters. The climate of Qeshm is warm and humid summers with scattered winds. The winters, are generally mild and spring like. The annual median of the daily average temperature is 27 degrees centigrade and the annual average of the maximum daily temperature is 32 degrees centigrade. The island’s average humidity is 74, with a maximum rainfall of 456 mm, and a minimum of 41 mm, annually. There are 200 hectares of Mangrove sea forest and also tropical plants and trees with palm groves in Qeshm. Because of the tropical climate of the island, around 200 species of birds migrate or reside in natural Hara forest habitats. Among the wild life of Qeshm, eagle, fox and sea turtles are recognized in the island. Qeshm is one of the most important and largest Persian Gulf islands that recently, due to the new government policies, converted to one of the free Commercial-Industrial and touristy area. This island accommodates thousands Iranian and foreign tourists every year (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Qeshm Island in southern Iran

Sampling methods

The present study was conducted in Qeshm Island, Hormozgan Province, 2006–2007. The island divided into 20 regions and samplings were performed from over 20 stations with the aim of determining the ant species in the island. Each station was divided in 10 points of measure disposed in a regular grid in a 20 × 20 meters square. Sampling was carried out directly by searching the ant nests. Two different methods were used to collect the specimens of ants. Ten non-attractive pitfall traps were laid for 7 d on each station. They were grouped by two and placed in five points with 50 cm from each other. Each group was itself distant from the other two groups by 10 meters in a line. Pitfall traps consisted of plastic jars of fifty-five millimetre diameter and thirty-five millimetres deep, containers filled with 30 ml of ethanol at 35%. The second method was active collection. Specimens from nests or surrounding areas were transferred to the containers filled with ethanol at 70% by paintbrush. Visual observations were performed on different days at sample sites.

All specimens preserved in dish and relative information was recorded. Specimens were deposited in the Medical Arthropods Museum, the School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences. The specimens were identified using the morphological keys of Bolton (1994), Collingwood and Agosti (1996) and Shattuck and Barnett (2001).

Results

The total number of samples identified was 1359. Six species of ants were identified belonging to three subfamilies includes Formicinae, Dolichoderinae, Myrmicinae. Of these six species, the most common was P. sennaarensis subfamily Ponerinea (41%), collected in pitfall traps and active collection on all twenty stations in urban and rural areas of the island (Table 1).

Table 1.

Locations where P. sannaarensis collected in Qeshm Island

| No. | Collection site | No of observed colony | Location |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Qeshm | 18 | Resident area, parks, open fields and wharf |

| 2 | Dargahan | 7 | Resident area, open fields and roadside plantations |

| 3 | Pay posht | 3 | Resident area |

| 4 | Laft port | 5 | Resident area |

| 5 | Gorzine | 2 | Resident area |

| 6 | Tabl | 6 | Resident area |

| 7 | Doolab | 5 | Resident area |

| 8 | Band Basaaid | 3 | Resident area |

| 9 | Doostkoh | 5 | Resident area |

| 10 | Namakdan | 6 | Resident area |

| 11 | Salkh | 3 | Resident area |

| 12 | Direstan | 2 | Resident area |

| 13 | Masn Port | 3 | Resident area |

| 14 | Sosa Port | 4 | Resident area |

| 15 | Rhamkan | 7 | Resident area and roadside plantations |

| 16 | Direstan and Air port | 7 | Resident area |

| 17 | Toorian | 8 | Resident area and roadside plantations |

| 18 | Rham chah | 12 | Resident area and roadside plantations |

| 19 | Toola | 2 | Resident area |

| 20 | Tombak | 4 | Resident area |

The other ants were identified as follow: P. lacteipennis Smith (Subfamily Formicinae) 23%, Camponotus fellah Dall Torre (Subfamily Formicinae) 16%, Cataglyphis niger Andre (Subfamily Formicinae) 9%, Tapinoma simrothi Krausse (Subfamily Dolichoderinae) 7% and Messor galla Mayr (Subfamily Myrmicinae) 4%.

Pachycondyla sennaarensis was the most common ant in various parts of the island. They are able to establish their colonies in every type of human environment present in Qeshm. The species distributed throughout Qeshmisland, which is the southern limit of its distribution in Iran (Table 1).

This taxon is not an aggressive species through its distribution in the island. It feeds mainly on food waste in urban area but it also feeds on dead insects and attracts to sugary substances. In addition, they are scavenger or predator in some parts of the island. Their nests generally open on to the surface with circular apertures, each 3–5 mm in diameter in the yards, gardens, parks and roadside plantations partially exposed to the sun. However, they are able to build their nest inside the human premises. In one case, we found their nest in the third floor of a shopping centre. In other case, the nest was built in second floor of a house in Qeshm.

Discussion

By far the most common species we found on Qeshm was P. sennaarensis Mayr (1862) described Pachycondyla sennaarensis from Sennaar, Sudan (13.55N, 33.60E). Emery (1881) first reported P. sennaarensis on the Arabian Peninsula, from three sites in Yemen. Later reports have recorded P. sennaarensis from many parts of tropical Africa e.g., Angola, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Congo, Djibouti, Ethiopia, the Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, and Zaire; (Taylor 2007) and the Arabian Penninsula e.g., Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, UAE, and Yemen (Collingwood 1985, Collingwood and Agosti, 1996, Collingwood et al. 1997, Collingwood and van Harten 2001, 2005). Recently, several authors have reported P. sennaarensis from South-eastern Iran, adjacent to the Arabian Peninsula (Tirgari et al. 2004, Tirgari and Paknia 2004, Tirgari and Paknia 2005, Akbarzadeh et al. 2006 a, b, Paknia 2006). Paknia (2006) considered P. sennaarensis as an exotic species to Iran, its near continuous range across Africa and Arabia. Other studies indicated that the species tend to have widespread towards the north of the country (Tirgari and Paknia 2005).

We were surprised that our surveys found none of the major pantropical tramp ant species, such as P. longicornis or Tapinoma melanocephalum. This study did not even find the tramp Monomorium destructor, a species that is often a pest in semi-arid areas.

Although Akbarzadah et al. (2006 a, b) have recently used the “fire ant” for P. sennaarensis, it probably gives the false impression that this ant is related to genus Solenopsis. It seems that the common name “samsun ant” is more appropriate for P. sennaarensis and many authors use this name for the species in the region (Dibs et al. 1995, Tirgari et al. 2004, Tirgari and Paknia 2004, Tirgari and Paknia 2005, Al-Shahwan et al. 2006, Paknia 2006). Since P. chinensis is now called the “Asian needle ant”, based on their similarity in behaviour and biology, it could be called P. sennaarensis “African needle ant”.

This study revealed an enormous amount of the samsun ant, P. sennaarensis in resident areas in Qeshm. While this taxon described as an aggressive species in Africa and some countries in the Middle East (Collingwood 1985, Dib et al. 1995, Taylor 2007), it is not an aggressive species throughout its distribution in the island. Previous studies by Tirgari et al. in 2004 and Akbarzadeh et al. in 2006 have shown the threat of P. sennaarensis on human health in south and southeast corner of the country. Comparison between morphological characters of the samsun ant from Qeshm and Sistan va Baluchistan province showed that they are identical and belong to the same species.

Many ant species, particularly those of tropical and subtropical origins, are easily transported around the globe by human commerce (Morrison et al. 2004). However, the island has been one of the most important islands of Iran from ancient times and it could be postulated that it has been transported from other places by human commerce.

Although the behaviour, nesting and social biology of P. sennaarensis are diverse in different parts of the world, it seems the species shares the same characters in its distribution in southern parts of Iran, which described by different authors (Tirgari et al. 2004, Tirgari and Paknia 2004,Tirgari and Paknia 2005, Akbarzadeh et al. 2006 a, b, Paknia 2006). They live in colonies and make their nests in ground. The majority of them make their nest near buildings, gardens, parks and roadsides.

The food preference of P. sennaarensis is varied in different part of the world. While in Africa, it is generally granivorous (Dejean and Lachaud 1994), in Qeshm the species feeds on human food and waste mainly. In such situation, it can consider as a commensal species. It appears this habit dependent on environmental factors, fauna and flora of the region and more importantly the availability of food. However, the species generally can be described as an omnivorous species, which feed on every available food sources such as food waste, fruits, nectarines or homopteran honeydew, small arthropods and dead animals. In urban area of the island, they also prefer to feed on the human’s food.

Besides, as they live in colonies with a few dozen to a few thousand workers, it shows their potential as a real threat of public health to the residents and visitors. Although their control is very difficult, knowledge of ant biology is essential for successful control programs.

The strategic location of Qeshm in the Persian Gulf and increase commercial movements in the recent years needs more attention for related organization to prevent entering pest ant species. It is important to support those researches aimed to identify species composition, the ecology and behaviour of native either exotic ant in the region based on environmental factors. Besides, as there are no regional pest ant control programs in the Persian Gulf region, it is need to achieve, develop and improve safe strategies for the local and regional control of pest ant.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Tehran University of Medical Sciences and Qeshm branch of Islamic Azad University for their support. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Akbarzadeh K, Tirgari S, Nateghpour M, Abaie MR. The first occurrence of Fire Ant Pachyconcdyla Sennaarensis (Hym: Formicidae), southeastern Iran. P J Biol Sci. 2006a;9(4):606–609. [Google Scholar]

- Akbarzadeh K, Tirgari S, Nateghpour M, Abaie MR. Medical importance of Fire Ant Pachyconcdyla Sennaarensis in Iranshahr and Sarbaz Counties, southeastern of Iran. J Med Sci. 2006b;6(5):866–869. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Shahwan M, Al-Khenaizan S, Al-Khalifa M. Black Samsun ant induced anaphylaxis in Saudi Arabia: the first report. Saudi Med J. 2006;27(11):1761–1763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astruc C, Julien JF, Errard C, Lenior A. 2004. Phylogeny of ants (Formicidae) based on morphology and DNA sequence data. Mol Phylogenet Evol, Available at: www.sciencedirect.com. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Bolton B. Identification of the ant genera of the world. Belknap Press; Harvard: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Bolton B. A New General Catalogue of Ants of the World. Belknap Press; Harvard: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Borror DJ, Triplehorn CA, Johnson NF. An Introduction to the Study of Insects. 6th ed. Saunders College Publishing; Philadelphia: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Collingwood CA. Hymenoptera: Fam. Formicidae of Saudi Arabia. Fauna Saudi Arabia. 1985;7:230–302. [Google Scholar]

- Collingwood CA, Agosti D. Formicidae (Insects: Hymenoptera) of Saudi Arabia (Part 2) Fauna Saudi Arabia. 1996;15:300–385. [Google Scholar]

- Collingwood A, Tigar BJ, Agosti D. Introduced ants in the United Arab Emirates. J Arid Environ. 1997;37:505–512. [Google Scholar]

- Collingwood CA, van Harten A. Additions to the ant fauna of Yemen. Esp Buche Entomol. 2001;8:559–568. [Google Scholar]

- Collingwood CA, van Harten A. Further additions to the ant fauna (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Yemen. Zool Middle East. 2005;35:73–78. [Google Scholar]

- Dejean A, Lachaud JP. Ecology and behavior of the seed eating ponerine Brachyponera sennaarensis (Mayr) Insect Soc. 1994;41:191–210. [Google Scholar]

- Dib G, Guerin B, Banks WA, Leynadier F. Systemic reactions to the Samsun ant: an IgE-mediated hypersensitivity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1995;96:465–72. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(95)70288-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery C. Spedizione Italiana nell’ Africa Equatoriale. Risultati Zoologici Formiche. Ann Mus Civ Stor Nat. 1881;16:270–276. [Google Scholar]

- Iran access (2007) Cities. Available at: http://www.iranaccess.com/iraninfo/Cities/qeshmataglance.htm

- Mayr G. Myrmecologische Studien. Verhandlungen der k.k. Verh Zool Bot Ges. 1862;12:649–776. [Google Scholar]

- McGlynn TP. The worldwide transfer of ants: geographical distribution and ecological invasions. J Biogeography. 1999;26:535–548. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammed OB, Hussein HS, Elowni EE. The ant, Pachycondyla sennaarensis (Mayr) as an intermediate host for the poultry cestode, Raillietina tetragona (Molin) Vet Res Communication. 1988;12:325–327. doi: 10.1007/BF00343251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moller H. Lessons for invasion theory from social insects. Biol Cons. 1996;78:125–42. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison LW, Porter SD, Daniels E, Korzukhin MD. Potential global range expansion of the invasive fire ant, Solenopsis invicta. Biol Invasions. 2004;6:183–191. [Google Scholar]

- Orivel J, Dejean A. Comparative effect of the venoms of ant of the genus Pachycondyla (Hymenoptera: Ponerinae) Toxicon. 2001;39:195–201. doi: 10.1016/s0041-0101(00)00113-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paknia O. Distribution of the introduced Ponerine ant Pachyconcdyla Sennaarensis (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) in Iran. Myrmecol Nachr. 2006;8:235–238. [Google Scholar]

- Passera L. Characteristics of Tramp Species. In: Williams DF, editor. Exotic Ants Biology, Impact, and Control of Introduced Species. Westview Press; Boulder CO: 1994. pp. 23–43. [Google Scholar]

- Wikipedia Qeshm. 2009. Available From: www.en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Qeshm.

- Shattuck SO, Bernet NJ. Australian Ant Online, Copyright CSIRO Australia. 2001. Available at: http://www.ento.csiro.au/science/ants/default.htm.

- Smith F. Catalogue of Hymenopterous Insects in the Collection of the British Museum, 6. Formicidae; London: 1858. [Google Scholar]

- Steen CJ, Janniger CK, Schutzer SE, Schwartz RA. Sting reactions to bees, wasps, and ants. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:91–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4632.2005.02391.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirgari S, Paknia O, Akbarzadeh K, Nateghpour M. First report on the presence and medical importance of stinging ant in Southern Iran (Hym: Formicidae: Ponerinae). XXII International Congress of Entomology; Brisbane, Queensland, Australia. 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Tirgari S, Paknia O. Additional records for the Iranian fauna of Formicidae (Hymenoptera) Zool Middle East. 2004;32:115–16. [Google Scholar]

- Tirgari S, Paknia O. First record of Ponerine ant (Pachycondyla sennaarensis) in Iran and some notes on its ecology. Zool Middle East. 2005;34:67–70. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor B. The Ants of (sub-Saharan) Africa. 2007. Available at: http://antbase.org/ants/africa/

- Wild AL. The genus Pachycondyla sennaarensis (Hymenoptera; Formicidae) in Paraguay. Bol Mus Hist Nat Parag. 2002;14(1–2):1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Williamson M, Fitter A. The varying success of invaders. Ecology. 1996;77:1661–1666. [Google Scholar]