Abstract

Background:

Cutaneous leishmaniasis due to Leishmania major has become a hot topic in Iran. The objective of this study was to determine some ecological aspects of sand flies in the study area.

Methods:

Sand flies were collected biweekly from indoors and outdoors fixed places in the selected villages, using 30 sticky paper traps from the beginning to the end of the active season of 2006 in Kerman Province, south of Iran. The flies were mounted and identified. Some blood fed and gravid female sand flies of rodent burrows and indoors were dissected and examined microscopically for natural promastigote infection of Leishmania parasite during August to September.

Results:

In total, 2439 specimens comprising 8 species (3 Phlebotomus and 5 Sergentomyia) were identified. The most common sand fly was P. papatasi and represented 87.1% of sand flies from indoors and 57.2% from outdoors. The activity of the species extended from April to end October. There are two peaks in the density curve of this species, one in June and the second in August. Natural promastigote infection was found in P. papatasi (12.7%).

Conclusion:

Phlebotomus papatasi is considered as a probable vector among gerbils and to humans with a high percentage of promastigote infection in this new focus of cutaneous leishmaniasis. The Bahraman area which until recently was unknown as an endemic area seems now to represent a focus of zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis transmission in Iran.

Keywords: Sand fly, Phlebotomus papatasi, Ecology, Leishmania major, Iran

Introduction

Phlebotomine sand flies are of widespread importance in the transmission of Leishmania pathogens in Iran. Increasing knowledge of sand flies is a cornerstone for establishing control measures to prevent leishmaniasis. Cutaneous and visceral leishmaniasis are endemic in Iran and remain to be a growing health threat to community, development and the environment in our country (Nadim et al. 1994). In the last two decades, the reported cases especially that of cutaneous leishmaniasis due to Leishmania major (CLM) have increased, and they were reported in areas that previously were known to be non- endemic by the public health services (Yaghoobi- Ershadi et al. 2001, 2004). This ignored form of neglected diseases is common in many rural areas of 17 out of the 30 provinces in Iran. About 80% of leishmaniasis cases reported in the country are of the CLM form.

Based on the reports of Control of Communicable Disease Unit, Rafsanjan Health Center, southern Iran, cutaneous leishmaniasis has not been presented in the area until 2002.

Since 2004 the reported cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis have suddenly increased in the study area. During 2003–2004, a total of 257 cases were officially reported all by passive case detection, most of them were from Bahraman District (Rafsanjan Health Center, unpublished data) 70 km from Rafsanjan County but this is probably a large underestimate. A preliminary survey showed that Rhombomys opimus was the main reservoir host and zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis is caused by L. major (School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, unpublished data).

Bahraman rural district (Noogh) of Rafsanjan County is an important agricultural axis from the point of view of growing pistachio in Iran so in depth entomological study must be carried out for preparation of control program to prevent the spread of disease to the neighboring villages and counties.

The objective of this study was to determine the species richness and relative abundance of sand flies, their distribution, monthly prevalence, number of generations and leishmanial infection of sand flies in the area.

Materials and Methods

Study site

The investigation was carried out from 10 April to 11 October 2006 in 5 villages, Javadieh, Aliabad, Ahmadabad, Najmabad and Daghogh, in the rural district of Bahraman, Rafsanjan County, Kerman Province, in the southeast of the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Rafsanjan County (29º 45′ N, 54º 50′– 56º 45′ E) is situated in the south east of Iran, 100 km northwest of Kerman at an altitude of 1460 m above sea level. It has a desert climate, very hot and dry in summer, cold and dry in winter. In 2006, the maximum mean monthly temperature was 31.9º C (July) and the minimum was 5.6º C (January). The total annual rainfall was 32.6 mm, with a monthly minimum of 0.2 mm (July and August) and maximum of 17.4 mm (January). The minimum mean monthly relative humidity was 14% in August and the maximum was 61% in March (Rafsanjan Meteorological Office, personal communication)

Sand flies sampling and monitoring

Sand flies were collected biweekly from fixed sites indoors (bedrooms, sitting rooms, toilets and stables) and outdoors (rodent burrows), using 30 sticky traps (castor oil-coated white papers 20cm×30cm) from the beginning to the end of active season (early April-mid October). Collected sand flies were stored in 70% ethanol. For species identification, sand flies were mounted in Puri's medium, produced at the medical entomology department (Smart et al. 1965) and identified after 24 h using the keys of Theodor and Mesghali (Theodor and Mesghali, 1964), then they were mounted and segregated by sex.

Detection of natural leptomonad infection in sand flies and their age determination

Sand fly collections were made during August to September in the selected villages using sticky traps around rodent burrows and aspirator from human dwellings. Collections were transferred to the laboratory at Rafsanjan health center for dissection. Blood fed females collected indoors were kept alive for 3–4 days to allow blood digestion and then dissected. All fed, gravid, semi-gravid and some unfed females collected from rodent burrows were dissected in a fresh drop of sterile saline (9/1000) and examined microscopically for natural promastigote infection in the alimentary canal. The physiological age of each female was determined by the presence or absence of granules in the accessory glands (Foster et al. 1970). All female sand flies were identified by the morphology of the pharyngeal armature and of the spermatheca (Theodor and Mesghali 1964).

Results

In this entomological survey, a total of 2439 adult sand flies (2152 from rodent burrows and 287 from indoor resting places) were collected and identified. They comprised 8 phlebotomine species with three Phlebotomus spp. and five Sergentomyia spp. (Table 1). The following five spices were found indoors: P. papatasi (87.1%); P. sergenti (0.7%); S. clydei (5.2%); S. sintoni (1.4%) and S. baghdadis (5.6%).

Table 1.

Richness, number, and relative abundance of sand fly species collected from indoors and outdoors in Bahraman rural district, Rafsanjan County, Kerman Province, Iran, 2006

| Collection site | Species | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| Richness | No. and (%) of sand flies | P. papatasi | P. sergenti | P. mongolensis | S. clydei | S. tiberiadis | S. sintoni | S. dentata | S. baghdadis | |

| No. | 250 | 2 | 0 | 15 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 16 | ||

| Indoors | 5 | % | 87.1 | 0.7 | 0 | 5.2 | 0 | 1.4 | 0 | 5.6 |

| Outdoors | 8 | No. | 1230 | 4 | 1 | 490 | 1 | 286 | 2 | 139 |

| % | 57.2 | 0.2 | 0.05 | 22.7 | 0.05 | 13.3 | 0.1 | 6.4 | ||

In the rodent burrows: P. papatasi (57.2%); P. sergenti (0.2%); P. mongolensis (0.05%); S.clydei (22.7%); S. tiberiadis (0.05%); S. sintoni (13.3%); S. dentata (0.1%) and S. baghdadis (6.4%).

The most prevalent species of indoors were P. papatasi, S. clydei and S. baghdadis and in case of outdoors they were P. papatasi, S. clydei, S. sintoni and S. baghdadis respectively. While other species were less frequent. The number and relative abundance of these species are given in Table 1.

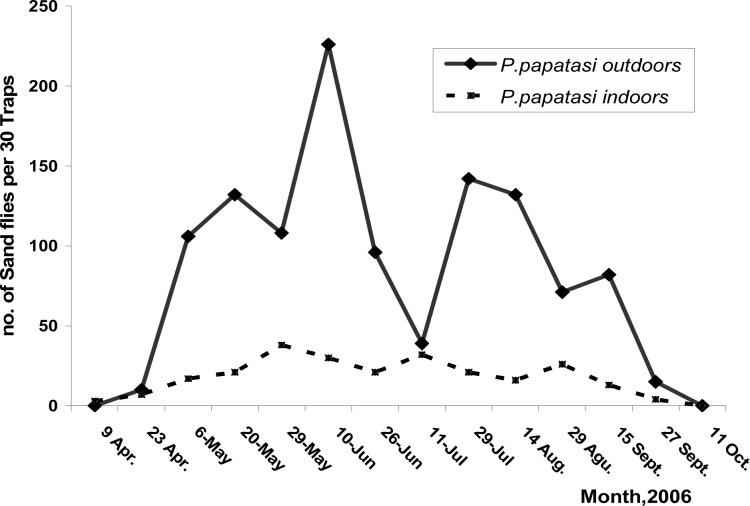

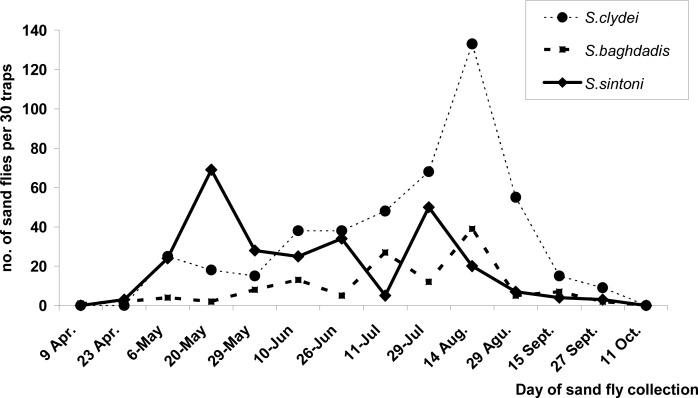

Phlebotomus papatasi started to appear in late April and disappeared in mid October in rodent burrows. There are two peaks in the density curve of this species, one in early June and the second in early August (Fig. 1) while, the first peak of activity of the species was at the end of May and the second in mid of July in indoors. The decrease in Sand fly density in mid October was most probably due to the cold weather and rains. There are also two peaks in the density curve of other species in rodent burrows in the area, one in late May or early June and the second in middle of August (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Monthly prevalence of P. papatasi in indoors and outdoors, Bahreman area, Rafsanjan County, 2006

Fig. 2.

Monthly prevalence of S. sintoni, S. baghdadis and S. clydei in Bahreman area, Rafsanjan County (rodent burrows), 2006

The sex ratio, i.e., number of males per 100 females of P. papatasi was 525 and 126 in indoors and rodent burrows respectively by the trapping method, sticky trap. P. papatasi (165), S. clydei (8), S. baghdadis (2) and S. sintoni (2) were collected in the vicinity of rodent burrows and were dissected. The results of these dissections showed that P. papatasi (12.7%) was infected with promastigotes. In three cases a large number of promasitgotes were observed in the gut as well as in the head of P. papatasi. In September 2006, six P. papatasi were collected from indoor places and dissected for the presence of promastigotes. All were negative (Table 2).

Table 2.

Natural promastigote infection in sand flies collected from rodent burrows, Bahraman rural district, Rafsanjan County, Kerman Province, Iran, summer 2006

| Site | Species | No. of sandflies dissected | Age group | No. of sandflies with promastigotes | % infected | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | P | ? | T | G | O | H | ||||

| Outdoors | P. papatasi | 165 | 13 | 141 | 11 | 21 | 18 | 3 | 3 | 12.7 |

| S. clydie | 8 | 1 | 6 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| S. baghdadis | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| S. sintoni | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Indoors | P. papatasi | 6 | 0 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

T, total; G, gut; O, oesophagus; H, head; P, parous; N, nuliparous;? age not known*

Some females that oviposited all of their eggs had accessory glands devoid of identifiable granules so recognizing parous sand flies from nuliparous ones was impossible.

Discussion

In the rural district of Bahraman, Kerman Province, cutaneous leishmaniasis due to L. major is a serious and increasing public health problem (Rafsanjan Health Center 2005, Kerman University of Medical Sciences, unpublished data). This paper presents the first report of sand flies in this focus. Eight species (three of Phlebotomus and five of Sergertomyia) were collected and identified. P. papatasi, a proven vector of L. major in Iran (Yaghoobi-Ershadi et al. 1995), is the most abundant species in Bahraman, specially in indoors.

Phlebotomus sergenti accounts for 0.7% and 0.2% of sand flies collected from indoors and outdoors respectively and was found only in some villages in the region. This species has never been implicated in the transmission of L. major in Iran. Only one male of P. mongolensis (0.05%) was collected from rodent burrows. With regard to its low frequency, it seems that the role of females of this species in the circulation of L. major among the rodents is doubtful in this part of Iran.

Phlebotomus papatasi has two peak activities in indoors and outdoors and it represents that the spices has two generations in the study area.

In routine collections by sticky traps in indoors and rodent burrows, males of P. papatasi predominate. The same results were also obtained on S. baghdadis and S. clydei in rodent burrows. In case of S. sintoni collected from outdoors, females were predominated. These results conformed to what was happened in other parts of the country such as Isfahan, Badrood, Natanz, Nikabad, Ardestan, Abardezh of Varamin, Sabzvar, Garmsar and so forth (Yahgoobi- Ershadi and Javadian 1997, Yaghoobi-Ershadi et al. 2001, 2004, 2003, Akhavan et al. 2007). It should be mentioned that the parameter, sex ratio varies greatly according to the trapping method and among species of Genus Phlebotomus and Sergentomyia (Schlein et al.1989).

The estimation of the age structure by dissection of the 165 females of P. papatasi from rodent burrows during the period of observation, showed an overall parous: nuliparous ratio of 141:13. It should be mentioned that about 6.7% of the females of this species that would have oviposited all of their eggs had accessory glands devoid of identifiable granules so recognizing parous sand flies from nuliparous ones were impossible.

Leishmanial infection rates of P. papatasi from rodent borrows of the other CLM foci in Iran (i.e. Abardezh, Ahwaz, Dezful, Isferayen, Lotfabad, Shush, Turkmen- Sahra, Isfaham and Badrood) ranged from 0.2% to 15.6% during 1967–2001 (Mesghali et al. 1967, Javadian et al. 1976, Nadim et al. 1994, Yaghoobi-Ershadi and Akhavan 1999).

In the present study, 12.7% of the vector species were infected. Comparison of the present findings with those obtained from Iran and other countries (Nadim et al. 1994, Janini et al. 1995) showed high natural infection rates with promastigotes from rodent burrows in Rafsanjan of southern Iran. Based upon these entomological data, P. papatasi is considered the most likely vector of CL in Rafsanjan. However, further studies are necessary to isolate Leishmania strains from P. papatasi and to characterize the genotype of Rafsanjan sand flies, taking into account current findings about the multi- locus microsatellite typing which has been employed to infer the population structure of P. papatasi in provinces of Khorasan, Khuzestan, Baluchistan, Azerbaijan, Isfahan, Fars and Yazd of Iran (Hamarsheh et al. 2009).

In conclusion, based on this survey, Bahraman rural district seems to be a typical focus of P. papatasi and L. major. It should be added to the list of CL foci due to L. major, so it is necessary to propose a new update map of the distribution of these foci in Iran.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to DM Gooya, Director General, Center of Communicable Diseases Control and Dr A Mozaffari from Rafsanjan University of Medical Sciences for their close collaboration. Our appreciation is also offered to M Alizadeh, K Mohammadi Poor and M Mozaffari from Rafsanjan Health Center for helping us in carrying out this program. This study was financially supported by National Institute of Health Research, Academic Pivot for Education and Research, Tehran University of Medical Sciences (Project No: 241.68.1) and partly by Tehran University of Medical Sciences (Grant number 3215-63-02-85 to Dr MR Yaghoobi-Ershadi). The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Akhavan AA, Yaghoobi-Ershadi MR, Hasibi F, Jafari R, Abdoli H, Arandian MH, Soleimani H, Zahraei- Ramazani AR, Mohebali M, Hajjarian H. Emergence of cutaneous leishmaniasis due to Leishmania major in a new focus of southern Iran. Iranian J Arthropod-Borne Dis. 2007;1(1):1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Foster WA, Tesfa- Yohannes TM, Tecle T. Studies on leishmaniasis in Ethiopia, II. Laboratory culture and biology of Phlebotomus longipes (Diptera: Psychodidae) Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1970;64:403–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamarsheh O, Presber W, Yaghoobi- Ershadi MR, Amro A, Al- Jawabreh A, Sawalha S, et al. Population structure and geographical subdivisions of the Leishmania major vector Phlebotomus papatasi as revealed by microsatellite variation. Med Vet Entomol. 2009;23:69–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2008.00784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janini R, Saliba E, Khoury S, Oumeish O, Adwan S, Kamhawi S. Incrimination of Phlebotomus papatasi as vector of Leishmania major in the southern Jordan valley. Med Vet Entomol. 1995;9:420–422. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.1995.tb00016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javadian E, Nadim A, Tahvildare- Bidruni GH, Assefi V. Epidemiology of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Iran B. Khorassan. Part V: Report on a focus of zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis in Isfarayen. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 1976;69:140–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesghali A, Seyedi- Rashti MA, Nadim A. Epidemiology of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Iran. Part II. Natural leptomonad infection of sand flies in the Meshed and Lotfabad areas. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 1967;60:514–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadim A, Javadian E, Seyedi- Rashti MA. Epidemiology of Leishmaniasis in Iran. In: Ardehali S S, Rezaei R, Nadim A, editors. Leishmania Parasite and Leishmaniasis. Tehran: University Publishing Center; 1994. pp. 176–208. [Google Scholar]

- Schlein Y, Yuval B, Jacobson RL. Leishmaniasis in the Jordan Valley: differential attraction of dispersing and breeding site populations of Phlebotomus papatasi (Diptera: Psychodidae) to manure and water. J Med Entomol. 1989;26:411–413. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/26.5.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smart J, Jordan K, Whittick RJ. Insects of Medical Importance. 4th ed. British Museum, Natural History, Adlen Press; Oxford: 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Theodor O, Mesghali A. On the phlebotomine of Iran. J Med Entomol. 1964;1(3):285–300. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/1.3.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaghoobi- Ershadi MR, Akhavan AA, Zahraei- Ramazani AR, Jalali- Zand AR, Piazak N. Bionomics of Phlebotomus papatasi (Diptera: Psychodidae) in an endemic focus of zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis in central Iran. J Vect Ecol. 2004;30(1):115–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaghoobi- Ershadi MR, Akhavan AA, Zahraei- Ramazani AR, Abai MR, Ebrahimi B, Vafaei- Nezhad R, Hanafi- Bojd AA, Jafari R. Epidemiological study in a new focus of cutaneous leishmaniasis in the Islamic Republic of Iran. East Mediterr Health J. 2003;9(4):816–826. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaghoobi- Ershadi MR, Hanafi- Bojd AA, Akhavan AA, Zahraei- Ramazani AR, Mohebali M. Epidemiological study in a new focus of cutaneous leishmaniasis due to Leishmania major in Ardestan town, Central Iran. Acta Trop. 2001;79:115–121. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(01)00085-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaghoobi- Ershadi MR, Akhavan AA. Entomological survey of sand flies (Diptera: Psychodidae) in a new focus of zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis in Iran. Acta Trop. 1999;73:321–326. doi: 10.1016/s0001-706x(99)00038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaghoobi- Ershadi MR, Javadian E. Studies on sand flies in a hyperendemic area of zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis in Iran. Indian J Med Res. 1997;105:61–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaghoobi- Ershadi MR, Javadian E, Tahvildare- Bidruni Leishmania major MON- 26 isolated from naturally infected Phlebotomus papatasi (Diptera: Psychodidae) in Isfahan, Iran. Acta Trop. 1995;59:279–282. doi: 10.1016/0001-706x(95)92834-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]