Abstract

Background:

Visceral leishmaniasis is caused by Leishmania infantum, transmitted to humans by bites of phlebotomine sand flies and is one of the most important public health problems in Iran. To identify the vector(s), an investigation was carried out in Bilesavar District, one of the important foci of the disease in Ardebil Province in northwestern Iran, during July–September 2008.

Methods:

Using sticky papers, 2,110 sand flies were collected from indoors (bedroom, guestroom, toilet and stable) and outdoors (wall cracks, crevices and animal burrows) and identified morphologically. Species-specific amplification of promastigotes revealed specific PCR products of L. infantum DNA.

Results:

Six sand fly species were found in the district, including: Phlebotomus perfiliewi transcaucasicus, P. papatasi, P. tobbi, P. sergenti, Sergentomyia dentata and S. sintoni. Phlebotomus perfiliewi transcaucasicus was the dominant species of the genus Phlebotomus (62.8%). Of 270 female dissected P. perfiliewi transcuacasicus, 4 (1.5%) were found naturally infected with promastigotes.

Conclusion:

Based on natural infections of P. perfiliewi transcaucasicus with L. infantum and the fact that it was the only species found infected with L. infantum, it seems, this sand fly could be the principal vector of visceral leishmaniasis in the region.

Keywords: Leishmania infantum, Phlebotomus perfiliewi transcuacasicus, nested PCR, Iran

Introduction

Leishmaniases are parasitic diseases of multifaceted clinical manifestations caused by infections with species of Leishmania. These diseases are widespread in the Old and New Worlds with great epidemiological diversity. Approximately, 700 species of sand flies are known but only 10% of these serve as disease vectors. Further, only about 30 species are important from a public health standpoint (WHO 1990, Desjeux 2000, Sharma 2008).

Visceral leishmaniasis (VL), commonly caused by Leishmania infantum in the Mediterranean region, the middle east and Latin America, affects approximately half a million new patients each year (Lachaud 2002). In the Mediterranean basin, domestic dogs (Canis familiaris) are the principle reservoir host and some species of sand-flies belonging to the subgenus Larroussius are the primary vectors (Oshaghi et al. 2009a).

Although VL occurs sporadically throughout Iran, the disease is endemic in several parts of northwestern Iran (Nadim et al. 1978, Davies et al. 1999, Mohebali et al. 1999, Rassi et al. 2004, 2005, 2009, Oshaghi et al. 2009b). The rate of infected sand flies in endemic areas and the identification of the infecting Leishmania parasites in the determined phlebotomine species are of prime importance in vectorial and epidemiological studies of leishmaniasis (Rodriguz et al. 1994). Three sand fly species, Phlebotomus perfiliewi transcaucasicus, P. (Larroussius) kandelakii Shchurenkova and P. (Larroussius) major Annandale are proven vectors in Iran (Rassi 2004, 2005, Azizi et al. 2008).

Two other species, P. (Larroussius) keshishiani Shchurenkova and P. (Paraphlebotomus) alexandri Sinton have been found naturally infected with promastigotes and are suspected vectors of VL in the country (Seyyedi-Rashti et al. 1963, Schönian et al. 2003, Azizi et al. 2006).

Leishmania parasites are directly detected by microscopic examination and all Leishmania species are very similar and their species identification is not possible morphologically (Schönian et al. 2003, Oshagi et al. 2009a) therefore we used nested PCR and PCR-RFLP methods in this study, because the main advantages of these methods are their sensitivity and specificity, independently of the number, stage and localization of the parasite in the digestive tract of the vector (Perez et al. 1994).

This study was carried out during Jul–Sep 2008 in rural areas of Bilesavar District, Ardebil Province, in northwestern Iran, to detect and identify Leishmania infection in sand flies.

Materials and Methods

Study area

The study was carried out in three villages of Gunpapagh, Odlu and Nazaralibalaghi, Bilesavar District, in northwestern Iran at an altitude of 1311 m (Fig. 1). The total population of the Bilesavar was about 55000 in 2008. The climate is very hot (up to 40°C) in the summer and quite cold (−27° C) during the winter. The summers are short, lasting from mid May to mid September. The main activities of the people are agriculture and animal husbandry.

Fig. 1.

Map of the study area located in Ardebil Province

Sand fly collection

Sand flies were collected biweekly from indoors (bedroom, guestroom, toilet and stable) and outdoors (wall cracks and crevices and animal burrows) using sticky papers (100 papers per village, 50 papers in outdoors and 50 papers indoors) during July–September 2008. Collected sand flies were removed from sticky papers using needles or fine brushes, dipped in 70% ethanol, were stored in 96% ethanol, and kept in −20 °C before dissection.

Sand fly identification

The sand fly specimens were washed in 1% detergent then twice in sterile distilled water. Each specimen was then dissected in fresh drop of sterile normal saline by cutting off the head and abdominal terminalia with sterilized forceps and single used mounted needles. The remainder of the body was stored in the sterile Eppendorf microtubes for DNA extraction. Specimens were mounted in Puri’s medium and identified using the identification keys of Theodor and Mesghali (1964) and Lewis (1982).

DNA extraction

DNA was extracted by using the Bioneer Genomic DNA Extraction Kit. Extraction was carried out by grinding of individual sand flies in a microtube using glass pestle and followed by kit protocol and stored at 4°C.

Detection and identification of Leishmania species

Initial screening of sand flies was performed by nested-PCR amplification of kinetoplast DNA (kDNA) using the protocol and primers (Table 1) already explained by Noyes et al. (1996). Amplification was carried out in two steps, both in the same tube. This PCR is able to identify promastigote infection of sand flies by producing a 680 bp for L. infantum/L. donovani, 560 bp for L. major, and a 750 bp for L. tropica.

Table 1.

Primers used in this study

| kDNA | First step | CSB2XF(forward): 5′-CGAGTA GCAGAAACTCCCGTTCA-3′ |

| CSB1XR(reverse): 5′-ATTTTTCGCGATTTTCGCAGAACG-3′ | ||

|

| ||

| Second step | 13Z(forward): 5′ (ACTGGGGGTTGGTGTAAAATAG-3′ | |

| LIR(reverse): 5′-TCGCAGAACGCCCCT-3′ | ||

|

| ||

| ITS1 | LITSR(forward): 5′-CTGGATCATTTTCCGATG-3′ | |

| L5.8S (reverse): 5′-TGATACCACTTATCGCACTT-3′ | ||

Further identification of the Leishmania parasites was done by using the ITS1-PCR (El Tai et al., 2000) followed by HaeIII digestion of the resulting amplicons described by Schonian et al. (2003). The set of primers (Table 1) forward LITSR and reverse L5.8S was used to amplify 340 bp of rDNA including parts of 3′ end of 18S rDNA gene, complete ITS1, and part of 5′ end of 5.8S rDNA gene. All of the amplification reactions were analyzed by 1–1.5% agarose gel electrophoresis, followed by ethidium bromide staining and visualization under UV light. Standard DNA fragments (100 bp ladder, Fermentas) were used to permit sizing.

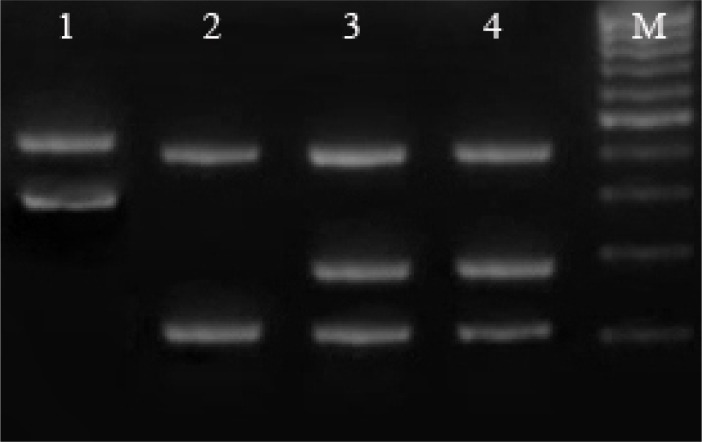

PCR products (15 μl) were digested with HaeIII without prior purification using conditions recommended by the supplier (Cinagen, Tehran, Iran). The restriction fragments were subjected to electrophoresis in 2% agarose and visualized under ultraviolet light after staining for 15 min in ethidium bromide (0.5 μg/ml). HaeIII digestion of ITS1 PCR reveals two fragments of 220 and 140 bp for L. major, the fragments of 200, 80 and 60 bp for L. donovani complex, and two fragments of 200 and a 60 bp for L. tropica.

Results

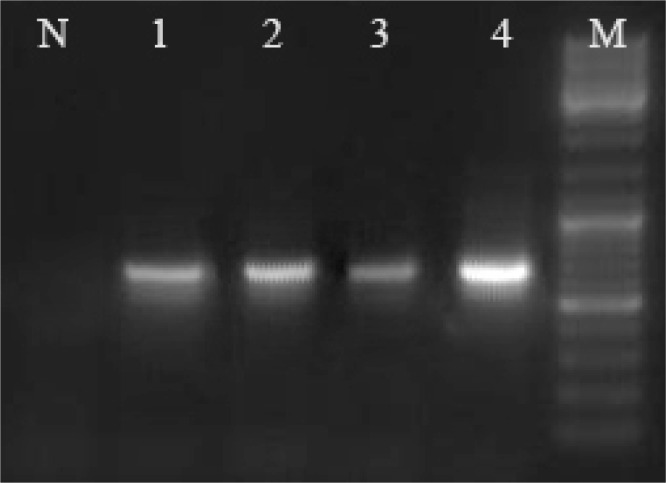

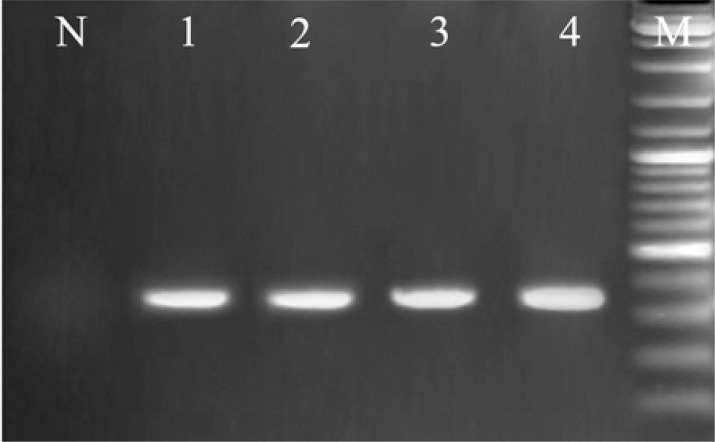

Altogether, 2,110 sand flies were collected and identified including P. perfiliewi transcaucasicus (62.8%), P. papatasi Scopoli (19.1%), P. tobbi Adler and theodor (3.9%), P. sergenti (10%), S. dentata Sinton and (1.8%), S. sintoni Pringle (2.4%). Among the collected specimens 433 females belonging to six species were screened for Leishmania infections (Table 2). Only 4 of 270 P. perfiliewi transcaucasus (1.5%) were observed to be naturally infected with L. infantum using nested PCR against minicircle kDNA molecules with 680 bp (Fig. 2). Furthermore ITS1 amplification by PCR primers followed by PCR-RFLP technique confirmed the L infantum DNA in two infected P. perfiliewi transcaucasus with 340 bp (Fig. 3). ITS1-PCR products were digested by HaeIII, for the Leishmania characterization. Since the length of PCR products for different species is different, for example, it is 360 bp for L. major and 340 bp for L. infantum, therefore the RFLP pattern is polymorphic for each species. The fragments of 220 and 140 bp for L. major, and the fragments of 200, 80 and 60 bp for L. infantum and two fragments of 200 and 60 bp were observed for L. tropica were diagnosed (Fig. 4). This is the first report of naturally infected of P. perfiliewi transcaucasus to L. infantum in Bilesavar District, Northwestern Iran.

Table 2.

Fauna and PCR results of collected sand flies in Bilesavar District, 2008

| Species | Male | Female | No of Infected | Leishmania species | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| NO | (%) | NO | (%) | kDNA | ITS | ||

| P. perfiliewi trancaucasicus | 1055 | 62.91 | 270 | 62.35 | 4 | 2 | L. infantum |

| P. papatasi | 356 | 21.22 | 47 | 10.85 | 0 | 0 | ________ |

| P. sergenti | 179 | 10.67 | 33 | 7.62 | 0 | 0 | ________ |

| P. tobbi | 45 | 2.69 | 35 | 8.09 | 0 | 0 | ________ |

| S. sintoni | 17 | 1.01 | 34 | 7.85 | 0 | 0 | ________ |

| S. dentate | 25 | 1.5 | 14 | 3.24 | 0 | 0 | ________ |

|

| |||||||

| Total | 1677 | 100 | 433 | 100 | 4 | 2 | |

Fig. 2.

kDNA PCR amplification of Leishmania stocks and L. infantum in P. perfiliewi transcaucasicus using nested-PCR. Lane N, Negative control, Lanes1, 2, 3 represent L. infantum in P. perfiliewi transcaucasicus (680 bp) and Lane 4 L. infantum (680 bp) positive control, M: 100 bp size marker (Fermentas)

Fig. 3.

Electerophoresis results of ITS1-RCR from Leishmania stocks and L. infantum in P. perfiliewi transcaucasicus, Lane N, negative control, Lanes 1, 2 represent L. infantum in P. perfiliewi transcaucasicus (340 bp), Lanes 3, 4 represent L. infantum positive controls (340 bp), M: 100 bp size marker (Fermentas)

Fig. 4.

Restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) patterns obtained from Leishmania stocks and L. infantum in P. perfiliewi transcaucasicus, Lanes 1, 2 and 4 represent L. major, L. tropica and L. infantum reference stocks respectively, Lane 3 is L. infantum in P. perfiliewi transcaucasicus, M: 50 bp size marker (Fermentas)

Discussion

Control of leishmaniasis depends on ecological and epidemiological information pertaining to the disease such as identification of preferred hosts and detection of natural infections in the vector(s). Finding naturally infected wild-caught specimens that are anthropophilic fulfills two essential requirements for incriminating a sand fly vector (Killick-Kendrick 1990). In endemic areas where more than one Leishmania species is present, diagnostic tools are required for the detection of parasites directly in samples and distinguish all relevant Leishmania species (Schönian et al. 2003). Characterization of Leishmania species is important, because different species may require special remedial method. On the other hand, such information is also valuable in epidemiologic studies where the distribution of Leishmania species in hosts and insect vectors is a urgent item in the controlling programs (El Tai et al. 2000, Schönian et al. 2003). Recently, molecular techniques (PCR) have been employed for vector incrimination of sand flies (Oshaghi et al. 2009a). The highly sensitive technique of PCR has been used for detecting Leishmania in sand flies in many endemic areas including Iran and India (Azizi et al. 2006, De Bruijn and Barker 1992, Oshaghi et al. 2009b, Mukherjee et al. 1997, Rassi et al. 2004, 2005, 2009). In the present study, infection of P. perfiliewi transcaucasicus by L. infantum was confirmed using molecular methods. It needs to mention that P. perfiliewi transcaucasicus was first found naturally infected with L. infantum in Germi District (other important focus of VL) adjoining to our study area (with 30 kilometers distance) in northwestern Iran (Rassi et al. 2009).Our study in Germi District showed that, 1.1% of dissected P. perfiliewi transcaucasicus sand flies were positive to L. infantum with 36.5% hematophagy preference to human (Anthropophilic Index) indicating a strong preference for human blood (Rassi et al. 2009). The apparent secondary preference of this species for dogs (23.5%), the main domestic reservoir of disease, may indicate that this species also plays an important role in transmission of VL to dogs (Rassi et al. 2009).

Based on high density of P. perfiliewi transcaucasicus, natural infected with Leishmania infantum, and high degree of anthropophily, it seems that that P. perfiliewi transcaucasicus could be the principal vector of VL in Bilesavar District northwestern Iran. Phlebotomus kandelakii was the first sand fly incriminated as a vector of VL in Meshginshahr city in northwestern Iran (Rassi et al. 2005). The high prevalence of P. perfiliewi transcaucasus revealed by this study is consistent with the reports of Lewis (1982) on the distribution of this species in Iran and the Republic of Azerbaijan, adjoining to our study area. This is the first report incriminating P. perfiliewi transcaucasicus as the main vector of VL due L. infantum in the region.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to staff of Bilesavar Health center for providing facilities to conduct this research and cooperation in the field sampling. This study received financial support from the School of Public Health, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, MSPH Thesis, 2010. The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests.

References

- Azizi K, Rassi Y, Javadian E, Motazedian MH, Asgari Q, Yaghoobi-Ershadi MR. First detection of Leishmania infantum in Phlebotomus (Larroussius) major (Diptera: Psychodidae) from Iran. J Med Entomol. 2008;45(4):726–731. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585(2008)45[726:fdolii]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azizi K, Rassi Y, Javadian E, Motazedian MH, Rafizadeh S, Yaghoobi-Ershadi MR, Mohebali M. Phlebotomus (Paraphlebotomus) alexandri: a Probable Vector Of Leishmania infantum In Iran. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2006;100(1):63–68. doi: 10.1179/136485906X78454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daliva AM, Momen H. Internal-Trascribed-Spacer (ITS) sequences used to explore polygenetic relationships within leishmania. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2002;94(6):651–654. doi: 10.1080/00034980050152085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies CR, Mazlomi-Gavani A. Age, acquired immunity and the risk of visceral leishmaniasis: A prospective study in Iran. Parasitol. 1999;119:247–257. doi: 10.1017/s0031182099004680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desjeux P. Leishmania/HIV coinfection, south-western Europe, 1990–1998. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- De Bruijn MH, Barker DC. Diagnosis of new world leishmaniasis: specific detection of species of the Leishmania braziliensis complex by amplification of kinetoplast DNA. Acta Trop. 1992;52:45–58. doi: 10.1016/0001-706x(92)90006-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Tai NO, Osam OF, Elfari M, Preseber W, Schönian G. Genetic heterogeneity of ribosomal internal transcribed spacer in clinical samples of Leishmania donovani spotted on filter paper as revealed by single-strand conformation polymorphisms and sequencing. Trans R Trop Med Hyg. 2000;94(5):575–579. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(00)90093-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajjaran H, Mohebali M, Razavi MR, Rezaei S, Kazemi B, Edrissian Gh, Moitabavi J, Hooshmand B. Identification of leishmania species isolated from human cutaneous leishmaniasis, using random amplified polymorphic DNA (Rapd-PCR) Iran J Publ Health. 2004;33(4):8–15. [Google Scholar]

- Kazemi-Rad E, Mohebali M, Hajjaran H, Rezaei S, Mamishi S. Diagnosis and characterization of leishmania species in giemsa-stained slides by PCR-RFLP. Iran J Public Health. 2008;37(1):54–60. [Google Scholar]

- Killick-Kendrick R. Phlebotomus vectors of visceral leishmaniasis, a review. Med Vet Entomol. 1990;4:1–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.1990.tb00255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachaud L, Marchergui-Hammami S, Chabbert E, Dereure J, Dedet J, Bastien P. Comparison of six PCR methods using peripheral blood for detection of canine visceral leishmaniasis. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:210–215. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.1.210-215.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis D J. A taxonomic review of the genus Phlebotomus (Diptera: Psychodidae) Bull Brit Mus Ent. 1982;45(2):154–161. [Google Scholar]

- Mohebali M, Hajjaran H, Hamzavi Y, Mobedi I, Arshi SH, Zarei Z, Akhoundi B, Naeini MK, Avizeh R, Fakhar M. Epidemiological aspects of canine visceral leishmaniosis in the islamic republic of Iran. Vet Parasitol. 1999;12:243–251. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2005.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee S, Hassan M Q, Ghosh A, Bhattacharya A, Adhya S. Leishmania DNA in Phlebotomus and Sergentomyia species during a Kala-Azar epidemic. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1997;57:423–425. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1997.57.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadim A, Javadian E, Tahvildar-Bidruni Gh, Mottaghi M, Abaei MR. Epidemiological aspects of Kala-Azar in Meshkin-Shahr, Iran: investigation on vectors. Iran J Public Health. 1992;21:61–72. [Google Scholar]

- Nadim A, Navid-Hamidi A, Javadian E, Tahvildar-Bidruni Gh, Amini H. present status of Kala Azar in Iran. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1978;27:25–28. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1978.27.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadim A, Javadian E. Key for species identification of sand flies (Phlebotominae, Diptera) of iran. Iran J Public Health. 1976;5:33–44. [Google Scholar]

- Noyes H, Camps AP, Chance M. Leishmania herreri (Kinetoplastida; Trypanosomatidae) is more closely related to endotrypanum (Kinetoplastida; Trypanosomatidae) than to leishmania. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1996;80(1):19–123. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(96)02679-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshaghi MA, Ravasan NM, Hide M, Javadian E, Rassi Y, Sadraie J, Mohebali M, Hajjaran H, Zarei Z, Mohtarami F. Phlebotomus perfiliewi transcaucasicus is circulating both Leishmania donovani and L. infantum in northwest Iran. Exp Parasitol. 2009b;123(3):218–225. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshaghi MA, Ravasan NM, Hide M, Javadian E, Rassi Y, Sedaghat MM, Mohebali M, Hajjaran H. Development of species-specific PCR and PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism assays for L. infantum/L. donovani discrimination. Exp Parasitol. 2009a;122:61–65. doi: 10.1016/j.exppara.2009.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez J E, Ogusuku E, Inga Natural leishmania infection of Lutzomyia spp in Peru. Trans Roy Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1994;88:161–164. doi: 10.1016/0035-9203(94)90276-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rassi Y, Javadian E, Nadim A, Rafizadeh S, Zahraii A, Azizi K, Mohebali M. Phlebotomus perfiliewi transcaucasicus, a vector of Leishmania infantum in northwestern Iran. J Med Entomol. 2009;46(5):1094–1098. doi: 10.1603/033.046.0516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rassi Y, Javadian E, Nadim A, Zahraii A, Vatandoost H, Motazedian MH, Azizi K, Mohebali M. Phlebotomus (Larroussius) kandelakii, the principle and proven vector of visceral leishmaniasis in north west of Iran. Pak J Biol Sci. 2005;8(12):1802–1806. [Google Scholar]

- Rassi Y, Kaverizadeh F, Javadian E, Mohebali M. First report on natural promastigote infection of Phlebotomus caucasicus in a new focus of visceral leishmaniasis in northwest of Iran. Iran J Public Health. 2004;33(4):70–72. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguz N, Guzman B, Rodas A. Diagnosis of cutaneous leishmaniasis and species discrimination of parasites by PCR and hybridization. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;9:2246–2252. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.9.2246-2252.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahabi Z, Seyyedi-Rashti MA, Nadim A, Jadian E, Kazemeini M, Abai MR. A preliminary report on the natural leptomonad infection of Phlebotomus major in an endemic focus of V.L. in Fars Province, south of Iran. Iran J Public Health. 1992;21:87–93. [Google Scholar]

- Schönian G, Nasereddin A, Dinse N, Schewynoh C, Schalling HD, Presbe W, Jaffe C. PCR diagnosis and characterization of leishmania in local and imported clinical samples. Diag Microbiol Infect. 2003;47(1):349–358. doi: 10.1016/s0732-8893(03)00093-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seyyedi-Rashti M, Sahabi Z, Kananio-Notash A. Phlebotomus (Larroussius) keshishiani; Shchurenkova, another vector of visceral leishmaniasis in Iran. Iran J Public Health. 1995;24:23–30. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma U, Singh S. Insect vectors of Leishmania: distribution, physiology and their control. J Vector Borne Dis. 2008;45:255–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO Control of the leishmaniases. Report of a WHO expert committee. Technical Report Series. 1990:793. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]