Abstract

Cancer resistance to therapy presents an ongoing and unsolved obstacle, which has clear impact on patient's survival. In order to address this problem, novel in vitro models have been established and are currently developed that enable data generation in a more physiological context. For example, extracellular-matrix- (ECM-) based scaffolds lead to the identification of integrins and integrin-associated signaling molecules as key promoters of cancer cell resistance to radio- and chemotherapy as well as modern molecular agents. In this paper, we discuss the dynamic nature of the interplay between ECM, integrins, cytoskeleton, nuclear matrix, and chromatin organization and how this affects the response of tumor cells to various kinds of cytotoxic anticancer agents.

1. Introduction

Resistance to radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and novel molecular drugs still represents one of the major obstacles in cancer therapy [1–3]. Limited effectiveness of therapy inevitably results in progressive disease or recurrence, thereby reducing the chance of cure for the patients. Phenotypically, two types can be distinguished: pretherapeutically existing and acquired resistances [4, 5]. Acquired resistance to irradiation is not known, but anticancer drugs, both conventional and molecular, frequently induce defense mechanisms [6–8]. To optimize the efficacy of cytotoxic agents, it is necessary to ameliorate drug delivery to the tumor and to better understand the underlying molecular mechanisms causing the resistance or evolving the defense process [5, 9].

In order to address the latter, we and others focused on a particular cellular substructure called focal adhesion (FA) [10–17]. FAs are membrane areas, which cells employ to interact with the surrounding extracellular matrix (ECM) via integrin adhesion receptors [10, 17–22]. Due to their multiprotein composition including growth factor receptors, signaling, and adapter proteins, FAs are huge hubs for signaling downstream to control critical cell functions such as cell survival, proliferation, differentiation, and invasion [11, 13, 14, 18, 20, 22–30]. The highly complex interplay between all of these signaling molecules secures homeostasis of single cells as well as of tissues in the context of responses to external signals from the microenvironment.

In tumor cells, according to the hallmarks of cancer [31], the proper physiological communication with the extracellular space is massively disturbed as a consequence of gene mutations and epigenetic modifications. Despite tumor growth-driving gene mutations, malignant cells often retain a high degree of susceptibility to certain extracellular factors [13, 31–34]. Prime examples are microenvironmental signals induced by cell adhesion to the ECM, adhesion to neighbouring cells, and growth factor receptor-ligand interactions, which all contribute to tumor progression and resistance to cytotoxic injury resulting from chemotherapeutic drugs and irradiation [12, 32, 35].

Keeping these facts in mind, a lot of effort was put in the improvement of in vitro models that best reflect in vivo growth conditions [11, 33, 36–40]. Since the advent of ECM-based 3D cell culture assays, a large body of evidence has suggested that conventional monolayer models do not reflect the complexity of tissues, phenotypes of cells, and modifications in transcriptome, proteome, phosphoproteome, protein-protein interactions, and signal transduction as the 3D models [11, 40–53].

From the therapeutic point of view, flat monolayer cell cultures contain an ECM-integrin-cytoskeleton connection very different from 3D grown cells [22, 40, 45, 46, 50, 51, 54, 55]. Moreover, cell growth in 3D ECM shows additional features like 3D multicellular spheroid growth [38, 56, 57]. Common to all 3D conditions is that the responsiveness to extracellular signals, drug, and radiation sensitivity as well as the physical forces between ECM and cytoskeleton for controlling chromatin organization and gene expression is very different from cells cultured in 2D. In this paper, we discuss cell-adhesion-mediated radio- and chemoresistance in the context of signaling and interplay between ECM, integrins, cytoskeleton, nuclear matrix, and chromatin organization.

2. Microenvironmental Signals Including Integrin Signaling Regulate Cellular Radio- and Chemosensitivity

Next to genetic alterations, the microenvironment plays an important role for carcinogenesis, tumor progression, and development of therapy-resistant phenotypes [31]. A closer look at the initiators and promoters of this multistep process suggests that a combination of both extra- and intracellular events commonly occurs to activate proto-oncogenes and deactivate tumor suppressor genes [31]. With regard to carcinogenesis, the particular reasons for cancer development can only be assumed in the minority of cases. Exploring a “mature” tumor provides a picture of the accumulated alterations in the various molecular determinants, which maintain unlimited growth and cause both existing and de novo therapy resistance mechanisms. In addition to the aforementioned genetic modifications, various soluble and structural microenvironmental factors like cytokines, chemokines, growth factors, and ECM essentially contribute to anticancer therapy defense mechanisms [13, 58–63].

Importantly, the ECM has structural, signaling, and storage functions. Thus, cells communicate with the surrounding ECM by mechanotransduction, by integrin-mediated adhesion, and by growth factor release and subsequent binding to their cognate receptors [21, 64–68]. For the role of mechanotransduction, only one issue has been evidently shown: changes in ECM stiffness induce perturbations of normal cell physiology preparing the ground for malignant transformation [42, 50, 69–71]. Open questions are, for example, how changes in ECM expression pattern of tumors impact on tumor cell behavior or how therapy-related alterations in tumor structure influence integrin-ECM interactions and intracellular signaling. For cell-adhesion-mediated radioresistance (CAM-RR) and cell-adhesion-mediated drug resistance (CAM-DR), integrins play critical roles [59, 72, 73].

Integrins are transmembrane receptors consisting of an α and a β chain. The 18 α and 8 β subunits form 24 known αβ-heterodimers dependent on cell type and function [20]. Integrin signals are transferred via the cell membrane in both directions. The binding activity of integrins is regulated from the inside and is called inside-out signaling; the interaction of integrins with ECM proteins for signal transduction into the cell is called outside-in signaling [10, 17–22]. These interactions essentially contribute to the regulation of various cellular functions like proliferation, survival, adhesion, differentiation, migration of cells, and tissue integrity [29, 41, 74–77].

For many years, it remained unknown how integrin signaling mediates tumor cell resistance. Well known were increased survival and reduced apoptosis in irradiated or drug-treated tumor cells of varying origin like head and neck, lung, pancreas, glioma, colon, breast, cervix, prostate, myeloma, and leukemia [58, 78–83]. But which signaling cascades do transmit these biochemical prosurvival signals? Physiologically, a large set of signal transduction and adapter molecules assembles at the cytoplasmic integrin domain upon integrin binding to ECM [17, 20]. Formation of mature FAs is critical for robust cell adhesion to ECM as well as accessibility to the intracellular signaling network for optimized regulation of key cellular processes [10, 16, 17]. For this signaling, integrins and growth factor receptors need to cooperatively and mutually interact [84]. Both adapter and nonreceptor bound signaling proteins are recruited to integrin or growth factor receptor tails upon activation. Through proteins such as focal adhesion kinase (FAK), small GTPases of the Rho family, PI3K/Akt, JNK, and ERK as well as the ternary protein complex consisting of integrin-linked kinase (ILK), PINCH1 and alpha-parvin (IPP), talin, alpha-actinin, and vinculin, biochemical signals are transferred as a result of integrin/RTK commitment [14, 15, 17, 85]. Despite prosurvival signaling, it remains to be solved what exact impact morphology has on cell survival. ECM-integrin-actin cytoskeletal and cell-cell-intermediate filament connections determine cell morphology, which consequently define function and integrity of single cells and tissues [33, 34, 37, 42, 62, 86]. A variety of molecules involved in these interactions have been shown to be altered in cancer. For example, integrins are overexpressed in many human cancers originating from the head and neck region [87], lung [88], prostate [89], ovary [90], and breast [91], while E-cadherin, as one of the key cell-cell contact proteins, is frequently reduced in its expression or absent [87, 92, 93].

These expression changes are highly likely to impact on tumor cell behavior. We know that this physical linkage between ECM and cytoskeleton via integrins is crucially involved in translating mechanical into chemical signals and in controlling cell morphology [37, 64, 68, 71, 94]. In vivo, the ECM determines the shape and stiffness of tissues [34, 62, 95]. Under conventional cell culture conditions, ex vivo cultured cells grow attached to artificial surfaces like cell culture plastic. Missing physiological cell-matrix contacts, as optimally met in a 3D environment, has dramatic impact on cell shape and cellular behavior in vitro [12, 13, 37, 41, 69, 86, 96]. A large number of studies demonstrated that 2D cultured cells lose important features of their original phenotype due to severe genetic, epigenetic, and signal transduction changes [42, 48, 71, 97]. As this is similarly true for normal and cancer cells, one might realize that tumor cells have a preserved susceptibility for external signals originating from the ECM or soluble extracellular factors. Obviously, these facts are contrary to observations demonstrating an independency from external input signals by autonomous activation of intracellular pathways or activating mutations in proto-oncogenes leading to anchorage-independent growth [13, 31, 32]. Doubtless, mutation-driven, constitutively activated oncogenes overrun antiproliferative signals from the outside, but the myriad of additional stimuli affecting the cells is very well perceived and processed.

Taking these features into account, one can easily imagine that ECM and integrins contribute to the regulation of the cellular reaction to genotoxic injury. Onoda et al. found that nonlethal irradiation of melanoma cells induces alphaIIb/beta 3 integrin upregulation and increased adhesion to fibronectin [98]. Further studies corroborated these findings in a variety of normal and transformed human cell lines [59, 72, 78, 99–101]. However, clinically important is the fact that integrin-mediated cell adhesion to the surrounding ECM confers resistance to ionizing radiation, cytotoxic drugs, and molecular agents [59, 72, 102–104]. In addition to CAM-DR [59] and CAM-RR [72], a new paradigm was entitled “Environment-Mediated Drug Resistance” by Meads and colleagues (EMDR) [60]. Intriguingly, these three phenomena have been confirmed in irradiated or drug-treated cells from various tumor entities like glioma, leukemia, and melanoma as well as carcinomas of the pancreas, lung, and head and neck [18, 25, 28, 59, 72, 105–107].

Besides increased cell survival, ECM attachment prolonged radiogenic G2/M cell cycle arrest [103, 108] and reduced the number of residual DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) and lethal chromosomal aberrations [40]. Also apoptotic cell death of small cell lung cancer cells was diminished under adhesion to laminin, fibronectin, or collagen type IV upon treatment with cytotoxic drugs [83].

Based on these findings, efforts are undertaken to uncover the underlying mechanisms and identify the cellular mediators and determinants involved in CAM-RR and CAM-DR. To elucidate therapeutic possibilities, small interfering RNA (siRNA) knockdown and antibody-mediated integrin inhibition are evaluated in different tumor cell lines with promising effects. In breast carcinoma, head and neck carcinoma, glioma, and leukemia cells, beta1 integrin targeting resulted in enhanced radiosensitivity and apoptosis [26, 27, 47, 80, 102, 109]. The pseudokinase ILK was clearly identified as antisurvival molecule in an attempt to classify the pro- and antisurvival function(s) of molecules acting downstream of integrins in cancer cells exposed to radiotherapy (reviewed in [110, 111]). Amongst others, this prosurvival group of molecules consists of FAK, JNK1, Akt1, PINCH1, and Caveolin-1 [55, 104, 112–117]. For example, overexpression of FAK protects 3D grown head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) cells from radiation-induced cell death [118], while siRNA-mediated silencing or pharmacological inhibition of FAK increases the radiosensitivity of different tumor cell lines from pancreatic cancer [112], breast cancer, colorectal cancer [119], and HNSCC [45, 55]. Furthermore, human melanoma cells become more sensitive to the chemotherapeutic agent 5-fuorouracil when FAK expression is downregulated [120]. In pancreatic cells, a reduction of FAK expression using microRNA for RNA interference leads to decreased FAK phosphorylation and repressed chemoresistance to gemcitabine [121]. Another interesting key player in this field is the LIM domain-containing particularly interesting new cysteine-histidine-rich 1 protein (PINCH1). Recent work from our group showed that knockdown of PINCH1 diminished the chemo- and radioresistance of diverse human carcinoma cells in vitro and in vivo [43, 122]. Mechanistically, PINCH1 was identified as novel Akt1 regulator by serving as platform for a regulatory interaction between protein phosphatase 1α (PP1α) and Akt1 [43]. According to the radiosensitization upon PINCH1 depletion, increased numbers of radiogenic DSBs were found in PINCH1 knockdown cell cultures indicating a role of PINCH1 in DNA repair processes [122]. On the basis of these findings, identification and targeting of molecules such as FAK or PINCH1 that critically regulates the cytotoxic drug and radiation response of tumor cells is a promising concept to overcome radio- and chemoresistance of tumor cells to improve cancer patient survival.

Additionally and of high importance for the current concepts of multimodal therapies, integrin-mediated cell-ECM interactions confer reduced efficacy of novel molecular agents/small molecules. In HNSCC, Eke and colleagues showed that adhesion to fibronectin attenuates the antiproliferative effect of a potent pharmacological epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) tyrosine kinase inhibitor [104]. Recent findings provide evidence for an essential role of ILK for EGFR targeting in HNSCC [113] and that EGFR overexpression mediates hypersusceptibility to the anti-EGFR antibody cetuximab in 3D grown HNSCC cell lines in a FAK-dependent manner [55].

In summary, integrin-mediated adhesion to ECM protects cancer cells from varying types of cell death intended by radiotherapy, chemotherapy, and molecular drugs. Monotherapeutic targeting of integrins and intracellular signaling molecules to overcome adhesion-mediated resistance is already part of first clinical trials [13]. Cilengitide, a peptide potently blocking ανβ3 and ανβ5 integrin, is currently under evaluation in clinical phase II trials in glioblastoma and other malignancies [123, 124]. Identification of novel potential cancer targets and evaluation of targeted approaches against these targets require extensive examination and, most importantly, consideration and usage of preclinical tumor models, which best reflect clinical circumstances.

3. The Impact of Focal Adhesion-Chromatin Linkage on Tumor Resistance against Irradiation and Cytotoxic Drugs

Regardless of normal or malignant cells, extracellular factors control critical cellular functions like survival, proliferation, and differentiation in a tissue-specific context [23, 37, 71, 97]. Studies using ex vivo cell cultures show the loss of morphological and functional properties in an artificial environment such as cell culture plastic as compared to ECM scaffolds [38, 69, 71]. Interesting studies in diverse tumor cell lines and normal cells showed that 3D growth in a matrix modifies gene and protein expression, cell survival, proliferation, differentiation, and metabolism in comparison to conventional 2D monolayer cell cultures [40, 42, 43, 46, 48, 116]. In line with these findings, osteosarcoma cells are protected against doxorubicin treatment [125] and head and neck and non-small-cell lung cancer cells display a reduced radiation sensitivity when grown in a 3D matrix in contrast to 2D [11, 40]. Beside these effects on cell survival upon cytotoxic injury, 3D growth conditions result in differential gene expression [126]. Global reorganization of chromatin through varying ECM compositions has been shown to be accompanied by changes in gene expression [94, 95, 127, 128]. Early work from Barcellos-Hoff and colleagues indicated that although polarized monolayers are formed, mammary epithelial cells fail to express milk proteins in 2D [23]. In 3D laminin-rich ECM, however, they formed alveolar-like structures with a central lumen and secreted milk proteins like casein [48, 49, 71, 95]. In this context, genes with ECM-responsive elements (EREs) were identified and helped to explain how the ECM participates in the regulation of gene expression [94, 128–130]. Furthermore, the pattern of gene expression is controlled by chromatin organization, which in turn is regulated by posttranslational modifications, that is, acetylation, phosphorylation, and methylation of nucleosomal histones [131, 132].

By integrating the above into an ECM-integrin-actin-nuclear membrane-nuclear matrix scenario, the ECM serves as one of the most powerful determinants of chromatin organization and gene expression [94, 130]. Concurrently, histones are upregulated as shown in 3D grown neuroblastoma cells [133] and tumor spheroids of melanoma cells [134], and histone acetylation is decreased to cooperatively control gene expression [46, 86, 135]. These highly dynamic actions are facilitated by histone acetyltransferases (HAT) and histone deacetylases (HDAC) [136, 137]. Gene expression in less condensed, euchromatic DNA regions is associated with histone hyperacetylation, while transcriptional repression occurs in more dense, heterochromatic DNA regions, by deacetylation [132, 138]. Recent own data demonstrate that growth in 3D ECM scaffolds decreases the levels of histone H3 acetylation in line with enhanced expression of the heterochromatin protein HP1α indicating a higher amount of heterochromatin [40]. Additionally, Le Beyec et al. highlighted the impact of cell-shape-induced changes in histone acetylation [46]. Cells cultured on polyHEMA showed a round cell morphology that led to histone deacetylation as consequence of changes in cell morphology but not adhesion [46]. These observations indicate that modifications in cell morphology impact on gene expression and thereby fundamentally determine tissue homeostasis and cellular responsiveness to external stress signals in a microenvironment-specific context [69].

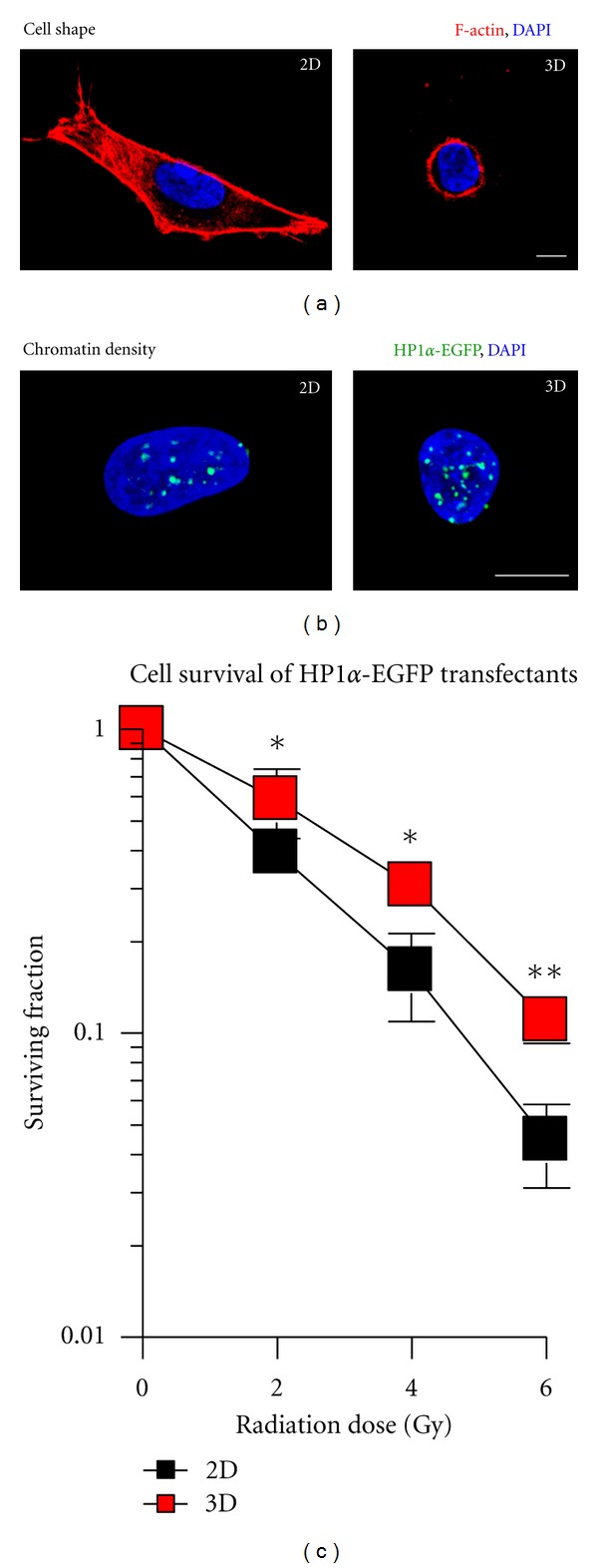

Hence, it is most likely that cells cultivated in 3D show also differences in pathways of DNA repair after treatment with DNA-damaging agents in comparison to 2D. Little is known about the distribution of radiogenic DSBs within areas with different chromatin condensation status. With regard to the increased radiation survival caused by reduced numbers of residual DSBs and a lower number of chromosomal aberrations, 3D cell growth induces larger amounts of heterochromatin in comparison to 2D (Figure 1) [40]. Furthermore, these data show DSB localization in eu- and heterochromatic DNA regions to be similar in 3D and tumor xenografts. Conversely to this 1 : 1 distribution, 2D cells show a 2 : 1 eu- to heterochromatin DSB distribution [40]. These results underline the findings that 3D cell culture models better mimic the in vivo situation than conventional 2D monolayers.

Figure 1.

Cell morphology, HP1α-EGFP distribution and clonogenic radiation survival of cells grown under three-dimensional (3D) growth conditions. (a) Comparison of cell morphology under 2D and 3D growth conditions (green; DAPI, blue, F-actin, red). (b) Fluorescence images of 2D and 3D grown A549 cells expressing HP1α-EGFP fusion protein. Images were acquired using laser scanning microscopy. (c) 2D and 3D clonogenic radiation survival of HP1α-EGFP expressing A549 cells irradiated with single doses of X-rays (0–6 Gy). Means ± SD and Student's t-test comparing 3D versus 2D conditions. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; n = 3; bar, 10 μm.

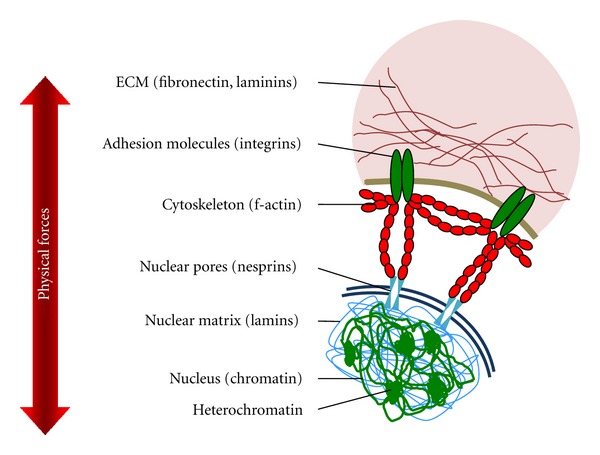

How are ECM and nuclear matrix linked? Cytoskeletal filaments physically bridge between integrins or other cell adhesion molecules and the nuclear matrix including chromatin structures (Figure 2) [17, 18, 64, 127, 139]. Thus, both cell-matrix-activated signal transduction and mechanical forces sensed at the surface promote structural rearrangements in the cytoplasm and in the nucleus [68, 127, 140]. The linkage between cytoskeletal filaments and the nuclear matrix was identified as a complex termed linker of nucleoskeleton and cytoskeleton (LINC) and contains nesprins, sun, and lamin proteins [68, 141–143]. Nesprins 1 and 2 are nuclear membrane proteins that bind actin filaments and interact with sun proteins at the inner nuclear membrane. To control nuclear organization and gene function according to external stimuli, lamin proteins, which are connected with the inner nuclear membrane, form a nuclear scaffold that can bind chromatin directly or indirectly via other nuclear proteins [142, 144].

Figure 2.

Schematic of the interplay between extracellular matrix (ECM), cytoskeleton, and nuclear matrix and the physical forces that affect cell morphology and chromatin organization.

Through this complex interplay between ECM, integrins, cytoskeleton and nuclear matrix, many changes such as genome reorganization and differential gene expression, alterations in cell morphology, and integrin-mediated signal transduction occur in response to microenvironmental factors [13, 23, 33, 129]. Importantly, this focal adhesion-chromatin linkage contributes to existing and acquired therapy resistance in cancer. An increased understanding of the underlying molecular mechanisms and the implementation of better translational cancer models will assist our efforts to optimize and personalize cancer therapy.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF-03ZIK041 to N. Cordes), the Saxon Ministry of Science and the Fine Arts and the European Regional Development Fund (Landesexzellenzinitiative Sachsen/EFRE ‘‘Europa fördert Sachsen,” 100066308), and the BEMER Int. AG (Liechtenstein).

References

- 1.Overgaard J. Hypoxic modification of radiotherapy in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Radiotherapy and Oncology. 2011;100(1):22–32. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mellinghoff IK, Sawyers CL. The emergence of resistance to targeted cancer therapeutics. Pharmacogenomics. 2002;3(5):603–623. doi: 10.1517/14622416.3.5.603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sawyers CL. Making progress through molecular attacks on cancer. Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology. 2005;70:479–482. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2005.70.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gottesman MM. Mechanisms of cancer drug resistance. Annual Review of Medicine. 2002;53:615–627. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.53.082901.103929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Longley DB, Johnston PG. Molecular mechanisms of drug resistance. Journal of Pathology. 2005;205(2):275–292. doi: 10.1002/path.1706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Desoize B, Jardillier JC. Multicellular resistance: a paradigm for clinical resistance? Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 2000;36(2-3):193–207. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(00)00086-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldman B. Multidrug resistance: can new drugs help chemotherapy score against cancer? Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2003;95(4):255–257. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.4.255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mendelsohn J, Baselga J. Epidermal growth factor receptor targeting in cancer. Seminars in Oncology. 2006;33(4):369–385. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baumann M, Krause M, Hill R. Exploring the role of cancer stem cells in radioresistance. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2008;8(7):545–554. doi: 10.1038/nrc2419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berrier AL, Yamada KM. Cell-matrix adhesion. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2007;213(3):565–573. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eke I, Deuse Y, Hehlgans S, et al. β 1 Integrin/FAK/cortactin signaling is essential for human head and neck cancer resistance to radiotherapy. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2012;122(4):1529–1540. doi: 10.1172/JCI61350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geiger B, Spatz JP, Bershadsky AD. Environmental sensing through focal adhesions. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2009;10(1):21–33. doi: 10.1038/nrm2593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hehlgans S, Haase M, Cordes N. Signalling via integrins: implications for cell survival and anticancer strategies. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2007;1775(1):163–180. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Legate KR, Montañez E, Kudlacek O, Fässler R. ILK, PINCH and parvin: the tIPP of integrin signalling. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2006;7(1):20–31. doi: 10.1038/nrm1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lo SH. Focal adhesions: what’s new inside. Developmental Biology. 2006;294(2):280–291. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mitra SK, Hanson DA, Schlaepfer DD. Focal adhesion kinase: in command and control of cell motility. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2005;6(1):56–68. doi: 10.1038/nrm1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moser M, Legate KR, Zent R, Fässler R. The tail of integrins, talin, and kindlins. Science. 2009;324(5929):895–899. doi: 10.1126/science.1163865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Danen EHJ. Integrins: regulators of tissue function and cancer progression. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2005;11(7):881–891. doi: 10.2174/1381612053381756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giancotti FG, Ruoslahti E. Integrin signaling. Science. 1999;285(5430):1028–1032. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5430.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hynes RO. Integrins: bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell. 2002;110(6):673–687. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00971-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwartz MA, Ingber DE. Integrating with integrins. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 1994;5(4):389–393. doi: 10.1091/mbc.5.4.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zutter MM. Integrin-mediated adhesion: tipping the balance between chemosensitivity and chemoresistance. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. 2007;608:87–100. doi: 10.1007/978-0-387-74039-3_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bissell MJ, Hall HG, Parry G. How does the extracellular matrix direct gene expression? Journal of Theoretical Biology. 1982;99(1):31–68. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(82)90388-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brakebusch C, Fässler R. β 1 integrin function in vivo: adhesion, migration and more. Cancer and Metastasis Reviews. 2005;24(3):403–411. doi: 10.1007/s10555-005-5132-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chung J, Tae HK. Integrin-dependent translational control: implication in cancer progression. Microscopy Research and Technique. 2008;71(5):380–386. doi: 10.1002/jemt.20566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cordes N, Park CC. β1 integrin as a molecular therapeutic target. International Journal of Radiation Biology. 2007;83(11-12):753–760. doi: 10.1080/09553000701639694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morello V, Cabodi S, Sigismund S, et al. β1 integrin controls EGFR signaling and tumorigenic properties of lung cancer cells. Oncogene. 2011;30:4087–4096. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramsay AG, Marshall JF, Hart IR. Integrin trafficking and its role in cancer metastasis. Cancer and Metastasis Reviews. 2007;26(3-4):567–578. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schwartz MA, Assoian RK. Integrins and cell proliferation: regulation of cyclin-dependent kinases via cytoplasmic signaling pathways. Journal of Cell Science. 2001;114(14):2553–2560. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.14.2553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamada KM, Pankov R, Cukierman E. Dimensions and dynamics in integrin function. Brazilian Journal of Medical and Biological Research. 2003;36(8):959–966. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2003000800001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144(5):646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barcellos-Hoff MH, Park C, Wright EG. Radiation and the microenvironment—tumorigenesis and therapy. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2005;5(11):867–875. doi: 10.1038/nrc1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eke I, Cordes N. Radiobiology goes 3D: how ECM and cell morphology impact on cell survival after irradiation. Radiotherapy and Oncology. 2011;99(3):271–278. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kim SH, Turnbull J, Guimond S. Extracellular matrix and cell signalling: the dynamic cooperation of integrin, proteoglycan and growth factor receptor. Journal of Endocrinology. 2011;209(2):139–151. doi: 10.1530/JOE-10-0377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hazlehurst LA, Landowski TH, Dalton WS. Role of the tumor microenvironment in mediating de novo resistance to drugs and physiological mediators of cell death. Oncogene. 2003;22(47):7396–7402. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Elsdale T, Bard J. Collagen substrata for studies on cell behavior. Journal of Cell Biology. 1972;54(3):626–637. doi: 10.1083/jcb.54.3.626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nelson CM, Bissell MJ. Of extracellular matrix, scaffolds, and signaling: tissue architecture regulates development, homeostasis, and cancer. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology. 2006;22:287–309. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.010305.104315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pampaloni F, Reynaud EG, Stelzer EHK. The third dimension bridges the gap between cell culture and live tissue. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2007;8(10):839–845. doi: 10.1038/nrm2236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Petersen OW, Ronnov-Jessen L, Howlett AR, Bissell MJ. Interaction with basement membrane serves to rapidly distinguish growth and differentiation pattern of normal and malignant human breast epithelial cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1992;89(19):9064–9068. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.19.9064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Storch K, Eke I, Borgmann K, et al. Three-dimensional cell growth confers radioresistance by chromatin density modification. Cancer Research. 2010;70(10):3925–3934. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Alavi A, Stupack DG. Cell survival in a three-dimensional matrix. Methods in Enzymology. 2007;426:85–101. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)26005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bissell MJ, Rizki A, Mian IS. Tissue architecture: the ultimate regulator of breast epithelial function. Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 2003;15(6):753–762. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2003.10.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eke I, Koch U, Hehlgans S, et al. PINCH1 regulates Akt1 activation and enhances radioresistance by inhibiting PP1α . Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2010;120(7):2516–2527. doi: 10.1172/JCI41078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hehlgans S, Eke I, Storch K, Haase M, Baretton GB, Cordes N. Caveolin-1 mediated radioresistance of 3D grown pancreatic cancer cells. Radiotherapy and Oncology. 2009;92(3):362–370. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hehlgans S, Lange I, Eke I, Cordes N. 3D cell cultures of human head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells are radiosensitized by the focal adhesion kinase inhibitor TAE226. Radiotherapy and Oncology. 2009;92(3):371–378. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Le Beyec J, Xu R, Lee SY, et al. Cell shape regulates global histone acetylation in human mammary epithelial cells. Experimental Cell Research. 2007;313(14):3066–3075. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Park CC, Zhang HJ, Yao ES, Park CJ, Bissell MJ. β1 integrin inhibition dramatically enhances radiotherapy efficacy in human breast cancer xenografts. Cancer Research. 2008;68(11):4398–4405. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roskelley CD, Desprez PY, Bissell MJ. Extracellular matrix-dependent tissue-specific gene expression in mammary epithelial cells requires both physical and biochemical signal transduction. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1994;91(26):12378–12382. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Streuli CH, Schmidhauser C, Bailey N, et al. Laminin mediates tissue-specific gene expression in mammary epithelia. Journal of Cell Biology. 1995;129(3):591–603. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.3.591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yamada KM, Cukierman E. Modeling tissue morphogenesis and cancer in 3D. Cell. 2007;130(4):601–610. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Eke I, Leonhardt F, Storch K, Hehlgans S, Cordes N. The small molecule inhibitor QLT0267 radiosensitizes squamous cell carcinoma cells of the head and neck. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006434.e6434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weaver VM, Petersen OW, Wang F, et al. Reversion of the malignant phenotype of human breast cells in three- dimensional culture and in vivo by integrin blocking antibodies. Journal of Cell Biology. 1997;137(1):231–245. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.1.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Xu R, Nelson CM, Muschler JL, Veiseh M, Vonderhaar BK, Bissell MJ. Sustained activation of STAT5 is essential for chromatin remodeling and maintenance of mammary-specifi c function. Journal of Cell Biology. 2009;184(1):57–66. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200807021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Durand RE. The influence of microenvironmental factors during cancer therapy. In Vivo. 1994;8(5):691–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Eke I, Cordes N. Dual targeting of EGFR and focal adhesion kinase in 3D grown HNSCC cell cultures. Radiotherapy and Oncology. 2011;99(3):279–286. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kunz-Schughart LA, Freyer JP, Hofstaedter F, Ebner R. The use of 3-D cultures for high-throughput screening: the multicellular spheroid model. Journal of Biomolecular Screening. 2004;9(4):273–285. doi: 10.1177/1087057104265040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dufau I, Frongia C, Sicard F, et al. Multicellular tumor spheroid model to evaluate spatio-temporal dynamics effect of chemotherapeutics: application to the gemcitabine/CHK1 inhibitor combination in pancreatic cancer. BMC Cancer. 2012;12, article 15 doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-12-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Damiano JS. Integrins as novel drug targets for overcoming innate drug resistance. Current Cancer Drug Targets. 2002;2(1):37–43. doi: 10.2174/1568009023334033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Damiano JS, Cress AE, Hazlehurst LA, Shtil AA, Dalton WS. Cell adhesion mediated drug resistance (CAM-DR): role of integrins and resistance to apoptosis in human myeloma cell lines. Blood. 1999;93(5):1658–1667. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Meads MB, Gatenby RA, Dalton WS. Environment-mediated drug resistance: a major contributor to minimal residual disease. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2009;9(9):665–674. doi: 10.1038/nrc2714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sandfort V, Koch U, Cordes N. Cell adhesion-mediated radioresistance revisited. International Journal of Radiation Biology. 2007;83(11-12):727–732. doi: 10.1080/09553000701694335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Weaver VM, Roskelley CD. Extracellular matrix: the central regulator of cell and tissue homeostasis. Trends in Cell Biology. 1997;7(1):40–42. doi: 10.1016/S0962-8924(97)30078-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Weigelt B, Lo AT, Park CC, Gray JW, Bissell MJ. HER2 signaling pathway activation and response of breast cancer cells to HER2-targeting agents is dependent strongly on the 3D microenvironment. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2010;122(1):35–43. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0502-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ingber DE. Tensegrity: the architectural basis of cellular mechanotransduction. Annual Review of Physiology. 1997;59:575–599. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.59.1.575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schwartz MA. Integrin signaling revisited. Trends in Cell Biology. 2001;11(12):466–470. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(01)02152-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Van der Flier A, Sonnenberg A. Function and interactions of integrins. Cell and Tissue Research. 2001;305(3):285–298. doi: 10.1007/s004410100417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang N, Ingber DE. Control of cytoskeletal mechanics by extracellular matrix, cell shape, and mechanical tension. Biophysical Journal. 1994;66(6):2181–2189. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(94)81014-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wang N, Tytell JD, Ingber DE. Mechanotransduction at a distance: mechanically coupling the extracellular matrix with the nucleus. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2009;10(1):75–82. doi: 10.1038/nrm2594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bissell MJ, Radisky DC, Rizki A, Weaver VM, Petersen OW. The organizing principle: microenvironmental influences in the normal and malignant breast. Differentiation. 2002;70(9-10):537–546. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.2002.700907.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Larsen M, Artym VV, Green JA, Yamada KM. The matrix reorganized: extracellular matrix remodeling and integrin signaling. Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 2006;18(5):463–471. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Xu R, Boudreau A, Bissell MJ. Tissue architecture and function: dynamic reciprocity via extra- and intra-cellular matrices. Cancer and Metastasis Reviews. 2009;28(1-2):167–176. doi: 10.1007/s10555-008-9178-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cordes N, Meineke V. Cell adhesion-mediated radioresistance (CAM-RR): extracellular matrix-dependent improvement of cell survival in human tumor and normal cells in vitro . Strahlentherapie und Onkologie. 2003;179(5):337–344. doi: 10.1007/s00066-003-1074-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Dalton WS. The tumor microenvironment: focus on myeloma. Cancer Treatment Reviews. 2003;29(supplement 1):11–19. doi: 10.1016/s0305-7372(03)00077-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Watt FM. Role of integrins in regulating epidermal adhesion, growth and differentiation. The EMBO Journal. 2002;21(15):3919–3926. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Blaschke RJ, Howlett AR, Desprez PY, Petersen OW, Bissell MJ. Cell differentiation by extracellular matrix components. Methods in Enzymology. 1995;245:535–556. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(94)45027-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.LaBarge MA, Petersen OW, Bissell MJ. Of microenvironments and mammary stem cells. Stem Cell Reviews. 2007;3(2):137–146. doi: 10.1007/s12015-007-0024-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Petersen OW, Ronnov-Jessen L, Weaver VM, Bissell MJ. Differentiation and cancer in the mammary gland: shedding light on an old dichotomy. Advances in Cancer Research. 1998;75:135–161. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)60741-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Cordes N, Blaese MA, Meineke V, Van Beuningen D. Ionizing radiation induces up-regulation of functional β1-integrin in human lung tumour cell lines in vitro . International Journal of Radiation Biology. 2002;78(5):347–357. doi: 10.1080/09553000110117340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Cordes N, Hansmeier B, Beinke C, Meineke V, Van Beuningen D. Irradiation differentially affects substratum-dependent survival, adhesion, and invasion of glioblastoma cell lines. British Journal of Cancer. 2003;89(11):2122–2132. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Cordes N, Seidler J, Durzok R, Geinitz H, Brakebusch C. β1-integrin-mediated signaling essentially contributes to cell survival after radiation-induced genotoxic injury. Oncogene. 2006;25(9):1378–1390. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hess F, Estrugo D, Fischer A, Belka C, Cordes N. Integrin-linked kinase interacts with caspase-9 and -8 in an adhesion-dependent manner for promoting radiation-induced apoptosis in human leukemia cells. Oncogene. 2007;26(10):1372–1384. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Meineke V, Gilbertz KP, Schilperoort K, et al. Ionizing radiation modulates cell surface integrin expression and adhesion of COLO-320 cells to collagen and fibronectin in vitro . Strahlentherapie und Onkologie. 2002;178(12):709–714. doi: 10.1007/s00066-002-0993-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sethi T, Rintoul RC, Moore SM, et al. Extracellular matrix proteins protect small cell lung cancer cells against apoptosis: a mechanism for small cell lung cancer growth and drug resistance in vivo . Nature Medicine. 1999;5(6):662–668. doi: 10.1038/9511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yamada KM, Even-Ram S. Integrin regulation of growth factor receptors. Nature Cell Biology. 2002;4(4):E75–E76. doi: 10.1038/ncb0402-e75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ingber DE, Dike L, Hansen L, et al. Cellular tensegrity: exploring how mechanical changes in the cytoskeleton regulate cell growth, migration, and tissue pattern during morphogenesis. International Review of Cytology. 1994;150:173–224. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)61542-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lelièvre S, Weaver VM, Bissell MJ. Extracellular matrix signaling from the cellular membrane skeleton to the nuclear skeleton: a model of gene regulation. Recent Progress in Hormone Research. 1996;51:417–432. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Eriksen JG, Steiniche T, Søgaard H, Overgaard J. Expression of integrins and E-cadherin in squamous cell carcinomas of the head and neck. APMIS. 2004;112(9):560–568. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0463.2004.apm1120902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Dingemans AC, van den Boogaart V, Vosse BA, van Suylen RJ, Griffioen AW, Thijssen VL. Integrin expression profiling identifies integrin alpha5 and beta1 as prognostic factors in early stage non-small cell lung cancer. Molecular Cancer. 2010;9, article 152 doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-9-152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dedhar S, Saulnier R, Nagel R, Overall CM. Specific alterations in the expression of α3β1 and α6β4 integrins in highly invasive and metastatic variants of human prostate carcinoma cells selected by in vitro invasion through reconstituted basement membrane. Clinical and Experimental Metastasis. 1993;11(5):391–400. doi: 10.1007/BF00132982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Ahmed N, Pansino F, Clyde R, et al. Overexpression of αvβ6 integrin in serous epithelial ovarian cancer regulates extracellular matrix degradation via the plasminogen activation cascade. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23(2):237–244. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.2.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Yao ES, Zhang H, Chen YY, et al. Increased β1 integrin is associated with decreased survival in invasive breast cancer. Cancer Research. 2007;67(2):659–664. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.desRochers TM, Shamis Y, Alt-Holland A, et al. The 3D tissue microenvironment modulates DNA methylation and E-cadherin expression in squamous cell carcinoma. Epigenetics. 2012;7(1):34–46. doi: 10.4161/epi.7.1.18546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Jayaraj P, Sen S, Sharma A, et al. Epigenetic inactivation of E-cadherin gene in Eyelid Sebaceous gland carcinoma. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.10968.x. British Journal of Dermatology. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Maniotis AJ, Valyi-Nagy K, Karavitis J, et al. Chromatin organization measured by AluI restriction enzyme changes with malignancy and is regulated by the extracellular matrix and the cytoskeleton. American Journal of Pathology. 2005;166(4):1187–1203. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62338-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bissell MJ, Weaver VM, Lelièvre SA, Wang F, Petersen OW, Schmeichel KL. Tissue structure, nuclear organization, and gene expression in normal and malignant breast. Cancer Research. 1999;59(7, supplement):1757s–1764s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Cukierman E, Pankov R, Yamada KM. Cell interactions with three-dimensional matrices. Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 2002;14(5):633–639. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(02)00364-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Alcaraz J, Xu R, Mori H, et al. Laminin and biomimetic extracellular elasticity enhance functional differentiation in mammary epithelia. The EMBO Journal. 2008;27(21):2829–2838. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2008.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Onoda JM, Piechocki MP, Honn KV. Radiation-induced increase in expression of the α(IIb)β3 integrin in melanoma cells: effects on metastatic potential. Radiation Research. 1992;130(3):281–288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Fuks Z, Vlodavsky I, Andreeff M, McLoughlin M, Haimovitz-Friedman A. Effects of extracellular matrix on the response of endothelial cells to radiation in vitro . European Journal of Cancer Part A. 1992;28(4-5):725–731. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(92)90104-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Meineke V, Müller K, Ridi R, et al. Development and evaluation of a skin organ model for the analysis of radiation effects. Strahlentherapie und Onkologie. 2004;180(2):102–108. doi: 10.1007/s00066-004-1134-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Vlodavsky I, Fuks Z, Ishai-Michaeli R, et al. Extracellular matrix-resident basic fibroblast growth factor: implication for the control of angiogenesis. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 1991;45(2):167–176. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240450208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Cordes N. Integrin-mediated cell-matrix interactions for prosurvivaland antiapoptotic signaling after genotoxic injury. Cancer Letters. 2006;242(1):11–19. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Cordes N, Van Beuningen D. Cell adhesion to the extracellular matrix protein fibronectin modulates radiation-dependent G2 phase arrest involving integrin-linked kinase (ILK) and glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β) in vitro . British Journal of Cancer. 2003;88(9):1470–1479. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Eke I, Sandfort V, Mischkus A, Baumann M, Cordes N. Antiproliferative effects of EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibition and radiation-induced genotoxic injury are attenuated by adhesion to fibronectin. Radiotherapy and Oncology. 2006;80(2):178–184. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2006.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Hazlehurst LA, Damiano JS, Buyuksal I, Pledger WJ, Dalton WS. Adhesion to fibronectin via β1 integrins regulates p27(kip1) levels and contributes to cell adhesion mediated drug resistance (CAM-DR) Oncogene. 2000;19(38):4319–4327. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Mochizuki S, Okada Y. ADAMs in cancer cell proliferation and progression. Cancer Science. 2007;98(5):621–628. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00434.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Weaver VM, Lelièvre S, Lakins JN, et al. β4 integrin-dependent formation of polarized three-dimensional architecture confers resistance to apoptosis in normal and malignant mammary epithelium. Cancer Cell. 2002;2(3):205–216. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00125-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kremer CL, Schmelz M, Cress AE. Integrin-dependent amplification of the G2 arrest induced by ionizing radiation. Prostate. 2006;66(1):88–96. doi: 10.1002/pros.20316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Estrugo D, Fischer A, Hess F, Scherthan H, Belka C, Cordes N. Ligand bound β1 integrins inhibit procaspase-8 for mediating cell adhesion-mediated drug and radiation resistance in human leukemia cells. PLoS ONE. 2007;2(3, article e269) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Eke I, Hehlgans S, Cordes N. There’s something about ILK. International Journal of Radiation Biology. 2009;85(11):929–936. doi: 10.3109/09553000903232892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Wickström SA, Lange A, Montanez E, Fässler R. The ILK/PINCH/parvin complex: the kinase is dead, long live the pseudokinase! The EMBO Journal. 2010;29(2):281–291. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2009.376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Cordes N, Frick S, Brunner TB, et al. Human pancreatic tumor cells are sensitized to ionizing radiation by knockdown of caveolin-1. Oncogene. 2007;26(48):6851–6862. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Eke I, Sandfort V, Storch K, Baumann M, Röper B, Cordes N. Pharmacological inhibition of EGFR tyrosine kinase affects ILK-mediated cellular radiosensitization in vitro . International Journal of Radiation Biology. 2007;83(11-12):793–802. doi: 10.1080/09553000701727549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Hehlgans S, Cordes N. Caveolin-1: an essential modulator of cancer cell radio-and chemoresistance. American Journal of Cancer Research. 2011;1:521–530. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Hehlgans S, Eke I, Cordes N. An essential role of integrin-linked kinase in the cellular radiosensitivity of normal fibroblasts during the process of cell adhesion and spreading. International Journal of Radiation Biology. 2007;83(11-12):769–779. doi: 10.1080/09553000701694327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Hehlgans S, Eke I, Deuse Y, Cordes N. Integrin-linked kinase: dispensable for radiation survival of three-dimensionally cultured fibroblasts. Radiotherapy and Oncology. 2008;86(3):329–335. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2007.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Kasahara T, Koguchi E, Funakoshi M, Aizu-yokota E, Sonoda Y. Antiapoptotic action of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) against ionizing radiation. Antioxidants and Redox Signaling. 2002;4(3):491–499. doi: 10.1089/15230860260196290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Hehlgans S, Eke I, Cordes N. Targeting FAK radiosensitizes 3-dimensional grown human HNSCC cells through reduced Akt1 and MEK1/2 signaling. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.01.065. International Journal of Radiation Oncology, Biology, Physics. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.McLean GW, Carragher NO, Avizienyte E, Evans J, Brunton VG, Frame MC. The role of focal-adhesion kinase in cancer—a new therapeutic opportunity. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2005;5(7):505–515. doi: 10.1038/nrc1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Smith CS, Golubovskaya VM, Peck E, et al. Effect of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) downregulation with FAK antisense oligonucleotides and 5-fluorouracil on the viability of melanoma cell lines. Melanoma Research. 2005;15(5):357–362. doi: 10.1097/00008390-200510000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Huanwen W, Zhiyong L, Xiaohua S, Xinyu R, Kai W, Tonghua L. Intrinsic chemoresistance to gemcitabine is associated with constitutive and laminin-induced phosphorylation of FAK in pancreatic cancer cell lines. Molecular Cancer. 2009;8, article 125 doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-8-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Sandfort V, Eke I, Cordes N. The role of the focal adhesion protein PINCH1 for the radiosensitivity of adhesion and suspension cell cultures. PLoS ONE. 2010;5(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013056.e13056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Reardon DA, Neyns B, Weller M, Tonn JC, Nabors LB, Stupp R. Cilengitide: an RGD pentapeptide ανβ3 and ανβ5 integrin inhibitor in development for glioblastoma and other malignancies. Future Oncology. 2011;7(3):339–354. doi: 10.2217/fon.11.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Gilbert MR, Kuhn J, Lamborn KR, et al. Cilengitide in patients with recurrent glioblastoma: the results of NABTC 03-02, a phase II trial with measures of treatment delivery. Journal of Neuro-Oncology. 2012;106(1):147–153. doi: 10.1007/s11060-011-0650-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Harisi R, Dudas J, Nagy-Olah J, Timar F, Szendroi M, Jeney A. Extracellular matrix induces doxorubicin-resistance in human osteosarcoma cells by suppression of p53 function. Cancer Biology and Therapy. 2007;6(8):1240–1246. doi: 10.4161/cbt.6.8.4443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Zschenker O, Streichert T, Hehlgans S, Cordes N. Genome-wide gene expression analysis in cancer cells reveals 3D growth to affect ECM and processes associated with cell adhesion but not DNA repair. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034279.e34279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Maniotis AJ, Chen CS, Ingber DE. Demonstration of mechanical connections between integrins, cytoskeletal filaments, and nucleoplasm that stabilize nuclear structure. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1997;94(3):849–854. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.3.849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Schmidhauser C, Casperson GF, Myers CA, Sanzo KT, Bolten S, Bissell MJ. A novel transcriptional enhancer is involved in the prolactin- and extracellular matrix-dependent regulation of β-casein gene expression. Molecular Biology of the Cell. 1992;3(6):699–709. doi: 10.1091/mbc.3.6.699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Lelièvre SA. Contributions of extracellular matrix signaling and tissue architecture to nuclear mechanisms and spatial organization of gene expression control. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 2009;1790(9):925–935. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Boudreau N, Myers C, Bissell MJ. From laminin to lamin: regulation of tissue-specific gene expression by the ECM. Trends in Cell Biology. 1995;5(1):1–4. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(00)88924-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Grewal SIS, Jia S. Heterochromatin revisited. Nature Reviews Genetics. 2007;8(1):35–46. doi: 10.1038/nrg2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Kouzarides T. Chromatin Modifications and Their Function. Cell. 2007;128(4):693–705. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Li GN, Livi LL, Gourd CM, Deweerd ES, Hoffman-Kim D. Genomic and morphological changes of neuroblastoma cells in response to three-dimensional matrices. Tissue Engineering. 2007;13(5):1035–1047. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.0251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Ghosh S, Spagnoli GC, Martin I, et al. Three-dimensional culture of melanoma cells profoundly affects gene expression profile: a high density oligonucleotide array study. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 2005;204(2):522–531. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Plachot C, Lelièvre SA. DNA methylation control of tissue polarity and cellular differentiation in the mammary epithelium. Experimental Cell Research. 2004;298(1):122–132. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Jenuwein T, Allis CD. Translating the histone code. Science. 2001;293(5532):1074–1080. doi: 10.1126/science.1063127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Xu WS, Parmigiani RB, Marks PA. Histone deacetylase inhibitors: molecular mechanisms of action. Oncogene. 2007;26(37):5541–5552. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Campos EI, Reinberg D. Histones: annotating chromatin. Annual Review of Genetics. 2009;43:559–599. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.032608.103928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Dufort CC, Paszek MJ, Weaver VM. Balancing forces: architectural control of mechanotransduction. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2011;12(5):308–319. doi: 10.1038/nrm3112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Pienta KJ, Coffey DS. Nuclear-cytoskeletal interactions: evidence for physical connections between the nucleus and cell periphery and their alteration by transformation. Journal of Cellular Biochemistry. 1992;49(4):357–365. doi: 10.1002/jcb.240490406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Crisp M, Liu Q, Roux K, et al. Coupling of the nucleus and cytoplasm: role of the LINC complex. Journal of Cell Biology. 2006;172(1):41–53. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200509124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Mellad JA, Warren DT, Shanahan CM. Nesprins LINC the nucleus and cytoskeleton. Current Opinion in Cell Biology. 2011;23(1):47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Worman HJ, Gundersen GG. Here come the SUNs: a nucleocytoskeletal missing link. Trends in Cell Biology. 2006;16(2):67–69. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Zhang Q, Skepper JN, Yang F, et al. Nesprins: a novel family of spectrin-repeat-containing proteins that localize to the nuclear membrane in multiple tissues. Journal of Cell Science. 2001;114(24):4485–4498. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.24.4485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]