Summary

Cancer chemotherapy disrupts the bone marrow (BM) microenvironment affecting steady-state proliferation, differentiation and maintenance of haematopoietic (HSC) and stromal stem and progenitor cells; yet the underlying mechanisms and recovery potential of chemotherapy-induced myelosuppression and bone loss remain unclear. While the CXCL12/CXCR4 chemotactic axis has been demonstrated to be critical in maintaining interactions between cells of the two lineages and progenitor cell homing to regions of need upon injury, whether it is involved in chemotherapy-induced BM damage and repair is not clear. Here, a rat model of chemotherapy treatment with the commonly used antimetabolite methotrexate (MTX) (five once-daily injections at 0.75 mg/kg/day) was used to investigate potential roles of CXCL12/CXCR4 axis in damage and recovery of the BM cell pool. Methotrexate treatment reduced marrow cellularity, which was accompanied by altered CXCL12 protein levels (increased in blood plasma but decreased in BM) and reduced CXCR4 mRNA expression in BM HSC cells. Accompanying the lower marrow CXCL12 protein levels (despite its increased mRNA expression in stromal cells) was increased gene and protein levels of metalloproteinase MMP-9 in bone and BM. Furthermore, recombinant MMP-9 was able to degrade CXCL12 in vitro. These findings suggest that MTX chemotherapy transiently alters BM cellularity and composition and that the reduced cellularity may be associated with increased MMP-9 expression and deregulated CXCL12/CXCR4 chemotactic signalling.

Keywords: bone marrow, chemotaxis, chemotherapy, haematopoietic cells, matrix metalloproteinase P-9, stromal cells

The bone marrow (BM) microenvironment is home to two distinct stem cell types, haematopoietic (HSC) and mesenchymal or stromal stem cells. The BM is the site of mesenchymal stem cell commitment and differentiation as well as the site of haematopoiesis and regulated release of HSC cells into the circulation throughout a lifetime (Randall & Weissman 1997; Han et al. 2006). Maintenance of an optimally functioning BM and as a result, haematopoiesis, bone formation and remodelling is largely dependent upon interactions between these two cell types and their progeny.

Stem cells are housed at endosteal niche sites, which are a supportive environment maintaining HSCs in a quiescent state via tight adhesive interactions between bone-lining osteoblasts and HSCs involving molecular interactions. The importance of the chemotactic CXCL12/CXCR4 axis in the homing and retention of stem cells has become more defined, as demonstrated by in utero death of CXCL12 or CXCR4 knockout mice because of major developmental defects, including haematopoiesis (Nagasawa et al. 1996; Nagasawa 2001). Chemokine CXCL12 is expressed by osteoblasts, BM stromal cells, endothelial and perivascular cells and is well established as a chemoattractant. CXCL12 binds to its G-protein-coupled receptor CXCR4, expressed on HSC stem and progenitor cells and a portion of stromal stem cells, illustrating the interaction between the two cell lineages. CXCL12 and CXCR4 were thought to be a monogamous pair until recent times, when an orphan receptor CXCR7 was identified to bind CXCL12 with a strong affinity (Balabanian et al. 2005; Burns et al. 2006). While CXCR7 deficiency also resulted in lethality, there were no disruptions to the foetal HSC system (Sierro et al. 2007). Therefore, the importance of the CXCL12/CXCR4 interaction in homing, mobilization and establishment of the BM microenvironment remains clear (Thelen & Thelen 2008; Georgiou et al. 2010).

Under steady-state conditions, the number of circulating HSC progenitors is low; however, under conditions of stress or injury when mobilization occurs, these numbers are found to increase (Siena et al. 1989; Fleming et al. 1993). Medical treatments such as myeloablative therapies including chemotherapy regimens induce cell cycling of quiescent stem cells and their mobilization out of the BM, increasing circulating HSC progenitors; thus, long-term ablative therapies reduce the HSC pool available to re-establish the continually depleted marrow cavity (Siena et al. 1989; Fleming et al. 1993; Wright et al. 2002; Kiefer et al. 2008; Nie et al. 2008).

Several possibilities have been suggested for the involvement of CXCL12/CXCR4 axis contributing to the regulation of stem cell retention, mobilization and homing. First, accumulation of neutrophils results in an increased release of neutrophil elastase (NE) and cathepsin G (Delgado et al. 2001; Petit et al. 2002; Devine et al. 2008), which have been shown to cleave both CXCL12 and CXCR4, disrupting their adhesive interaction (Levesque et al. 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004). As a result of this, HSCs held in a quiescent state at the endosteal niche move into the cell cycle. This remains controversial however, as mobilization in NE x CG-deficient mice remained normal (Levesque et al. 2004), indicating a NE and CG-independent mechanism of posttranslational CXCL12 or CXCR4 cleavage (Levesque et al. 2004). Secondly, associated with increased osteoclast activity under stress conditions is an increase in matrix-degrading enzyme, matrix metalloproteinase (MMP-9, gelatinase B), and the potent bone-resorbing protease cathepsin K, which have been associated with a reduced CXCL12 protein concentration (Levesque et al. 2004; Zannettino et al. 2005; Kollet et al. 2006; Gronthos & Zannettino 2007). Consistently, MMP-9 has been illustrated to directly cleave CXCL12 at its N-terminus (McQuibban et al. 2001), whereby its activity is regulated by its natural inhibitor, tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP-1), often found co-expressed by the same cell (Murphy et al. 1994; Ries et al. 1999). Thirdly, axis deregulation can be induced by reduced transcription of CXCL12 and/or CXCR4 in resident cells or by direct blockage of the CXCL12/CXCR4 interaction (Semerad et al. 2005; Christopher et al. 2009). Alternatively, a gradient change in CXCL12 protein in favour of the peripheral blood (PB) (Broxmeyer et al. 2005) over the BM has also been postulated as a possible cause of the observed migration out of the BM (Petit et al. 2002; Jin et al. 2008). However, the exact mechanism enabling mobilization/recovery to occur remains largely elusive and needs to be further studied.

Side effects of chemotherapy treatments are varied in their severity and targets, depending on the dosage and agents used. Bone marrow myelosuppression, indicated by reduced HSC cellularity and differentiation potential, has been demonstrated to be a side effect associated with cancer chemotherapy (Das et al. 2003, 2008; Meng et al. 2003; Abd-Allah et al. 2005). Similarly, steady-state maintenance of the stromal lineage is also disrupted, with high-dose chemotherapy resulting in a depleted osteogenic precursor population of the BM of adult cancer patients (Banfi et al. 2001), reducing osteogenic differentiation potential and bone formation (Ben-Ishay & Barak 2001; Davies et al. 2002a,b). Consequently, improved cancer patient survival has been associated with increased observations of long-term skeletal side effects, including osteoporosis and increased fracture risk in paediatric and adult cancer patients and survivors (Schriock et al. 1991; Halton et al. 1996; Ahmed et al. 1997; Haddy et al. 2001). We have recently shown that short-term treatment with the antimetabolite MTX causes decreased bone formation and osteoporosis-like effects in rat models (Xian et al. 2007, 2008) and reduces the BM stromal progenitor cell population, causing a switch in differentiation potential towards adipogenesis at the expense of osteogenesis (Georgiou et al. 2011). Therefore, as the mechanisms by which chemotherapy causes BM damage and bone defects are yet to be elucidated, this study utilized the short-term MTX model in an effort to identify whether the CXCL12/CXCR4 axis is associated with these defects and the subsequent recovery that ensues.

Materials and methods

Animal trials and tissue collection and processing

Sprague Dawley rats of approximately 150 g in body weight were used for a short-term trial receiving subcutaneous MTX administration at a therapeutic dose of 0.75 mg/kg for five consecutive days as described (Friedlander et al. 1984; Xian et al. 2007). Rats were euthanized at days 6, 9, 10, 12, 14 or 21 after the first dosing (n = 7–9 rats/group) to assess the time-course of injury and recovery of the BM microenvironment. A group of saline-injected rats were used as normal controls. The protocol followed the Australian Code of Practice for the Care and Use of Animals and was approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the Women’s and Children’s Hospital, Institute of Medical and Veterinary Science, and University of South Australia.

After euthanasia, a cardiac puncture was immediately performed to obtain PB in lithium-heparin collection tubes for obtaining plasma samples, after which tibiae, femurs and pelvises were dissected. To obtain BM cells for cell culture studies, the left tibia and left femur were flushed. For histology and immunohistochemical studies, the right tibial specimens were fixed in 10% formalin overnight and decalcified in Immuocal (Decal Corporation, Tallman, NY, USA) solution for 14 days at 4 °C prior to being bisected longitudinally with one half processed routinely and embedded in paraffin wax for producing 4-μm sections, which will be stained by H&E as previously described (Xian et al. 2006). The metaphyseal region of the right femur was collected, snap-frozen and stored at −80 °C for RNA extraction and gene expression studies.

Bone marrow cell isolation and cell culture

Bone marrow samples from both femurs, one tibia and both humeri obtained from the same animal were combined, resuspended in 2 ml of basal media and passed through a 19-gauge needle, followed by a 70-μm nylon filter cell strainer (BD Biosciences, Sydney, NSW, Australia) for the removal of contaminating particles. The suspension was diluted by the addition of an equal volume of PBS and then overlaid on 4 ml of Lymphoprep™ density gradient and centrifuged at a speed of 850 g for 20 min with the brake set to 0. The bone marrow mononuclear cell (BMMNC)-containing interface was collected and washed with PBS, and pelleted cells were resuspended in basal media for routine dye exclusion cell viability and density counts using Trypan blue (Sigma-Aldrich, Sydney, NSW, Australia). To obtain bone marrow stromal cells (BMSC) for further culture, 200 μl of the BM suspension was plated into T25 flasks and 1 ml into a T75 flask, maintained at 37 °C and 5% CO2 until 80% confluence was achieved (typically after 10 days).

Colony-forming unit-granulocyte macrophage (CFU-GM) assay

As a means to assess the effects of MTX treatment on changes to HSC lineage differentiation, CFU-GM assay was performed with BM cell specimens. Non-plastic adhering cells of the HSC lineage were plated out in MethoCult, a semi-solid methylcellulose gel containing cytokines (Stem Cell Technologies, Melbourne, Vic., Australia). The bone marrow mononuclear cells were plated out at 1.5 × 104 in 0.3 ml of MethoCult per well in a 24-well plate, with added stem cell factor, granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) and interleukin 3 (IL-3), which are the minimum requirements for colony formation and expansion based on previous studies (Hattori et al. 2001). After 14 days of culture at 37 °C and 5% CO2, cell growth was assessed and aggregates of 50 or more cells were counted as colonies. To assess the role of CXCL12 in the proliferation of both control specimens or MTX-treated HSC progenitors, 50 ng/ml recombinant CXCL12 (R&D Systems) was added to the MethoCult medium on the day of seeding together with or without 100 nM MTX (Li et al. 2004). Colony-forming unit-granulocyte macrophage colonies were assessed on day 11 of culture as colonies/1.5 × 104 MNCs.

CFU-fibroblast (CFU-F) assay

To assess the BM stromal population response to exogenous CXCL12 and MTX in vitro, isolated stromal cells were used to set up CFU-F assay as described (Fan et al. 2009). Briefly, 100 nM MTX or control was added to the basal medium of cultured BMSCs 24 h after seeding, and 50 ng/ml recombinant CXCL12 or control was added a further 24 h later. CFU-fibroblast colonies counted as aggregates of 50 or more cells were assessed after 14 days of culture and stained for both alkaline phosphatase (representing osteoprogenitor cell differentiation potential) and toluidine blue (representing total progenitor cell differentiation).

RNA isolation and RT-PCR gene expression analysis

RNA isolation

To assess gene expression of BM cells after MTX treatment in rats, isolated primary stromal cells were grown in a T75 flask with basal medium until confluence, at which time the cells were collected and frozen at −80 °C until time of RNA extraction. RNA isolation of BMSC pellet was performed using RNAqueous®-Micro Kit (Ambion; Applied Biosystems Pvt Ltd., Melbourne, Vic., Australia) following standard protocol, and RNA was further purified of contaminating DNA. For metaphyseal bone gene expression studies, frozen total metaphyseal bone specimens were ground to fine powder using a mortar and pestle and liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was then extracted using TRI reagent (Sigma, Australia). For gene expression studies of blood cells in PB, 1 ml whole blood was collected with a syringe containing EDTA and 500 μl was stored in a 2-ml tube preloaded with RNA-later at −80 °C. Isolation was performed using Mouse RiboPure™-Blood RNA Isolation Kit (Ambion; Applied Biosystems), which is also suitable for rat whole blood and whole BM RNA extraction, and the resulted RNA was purified of contaminating DNA using TURBO DNase-free Kit (Ambion; Applied Biosystems).

Real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

First-strand cDNA was reverse transcribed using a set of 20-μl reaction mixtures, and all specimens were standardized using 2 μg total RNA, containing 1 μl random decamers (50 ng/μl; GeneWorks, Adelaide, SA, Australia), 1 μl 10 mM dNTP mix and 1 μl Superscript™ III Reverse Transcriptase as instructed (Invitrogen Pty Ltd., Melbourne, Vic., Australia). cDNA was also synthesized without the addition of reverse transcriptase as a negative control. cDNA templates were used for the amplification by PCR. All primers (Table 1) were designed using primer blast to ensure forward and reverse primers in different exons and were obtained from GeneWorks. Design parameters were set at 80–150 bp in length, CG content 50–60% and Tm2 58–62. For RT-PCR of genes of interest, SYBER green® PCRs with the cDNA samples were run in parallel with internal control gene Cyclophilin A on a 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) as described (Xian et al. 2008; Chung et al. 2009; Fan et al. 2009). Relative expression against Cyclophilin A was calculated using the comparative Ct (2−ΔCt) method.

Table 1.

Primer pairs used in this study

| Gene of interest | Forward | Reverse |

|---|---|---|

| CXCL12 | ATCAGTGACGGTAAGCCAGTCA | TGCACACTTGTCTGTTGTTGCT |

| CXCR4 | ATGTGAGTTCGAGAGCGTCGT | TGGAATTGAGTGCATGCTGC |

| MMP-9 | TCGAAGGCGACCTCAAGTG | GCGGCAAGTCTTCGGTGTAG |

| Cyclophilin A | GAGCTGTTTGCAGACAAAGTTC | CCCTGGCACATGAATCCTG |

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for CXCL12, MMP-9 and TIMP-1

Protein concentrations of CXCL12, MMP-9 and TIMP-1 in the BM supernatant and/or blood plasma were determined by ELISA in specimens from rats treated with or without MTX. Bone marrow aspiration from individual rat pelvises with 250 μl of PBS was performed to collect the supernatant fraction of the BM. Similarly, PB plasma was collected from each individual rat and stored at −20 °C. For ELISA, samples were diluted 1:4, and standards were prepared with recombinant mouse CXCL12/SDF-1α, human MMP-9 or rat TIMP-1 (460-SD, 911-MP, 580-RT; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) species cross-reactivity in rats demonstrated by (Jung et al. 2006) and (Ma et al. 2010) respectively) in diluent with ranges of concentrations beginning from 5 ng/ml for CXCL12 and 2 ng/ml for MMP-9 and TIMP-1. Wells were coated with monoclonal anti-human/mouse CXCL12/SDF-1 antibody, anti-human MMP-9 antibody or anti-rat TIMP-1 antibody (MAB350, MAB936, MAB5802; R&D Systems) and stored at −20 °C overnight. After washes, wells were blocked with 1% BSA/PBS for 2 h, washed and added with 100 μl of the standards and samples (1:4). After being incubated for a further 2 h and washed, a biotinylated anti-human/mouse CXCL12/SDF-1 antibody, anti-human MMP-9 antibody or anti-rat TIMP-1 antibody (BAF310, BAF911, BAF580; R&D Systems) was added and incubated for 2 h. After wash, streptavidin-HRP (DY998; R&D Systems) and tetramethylbenzidine liquid substrate (P7998; Sigma-Aldrich) were used for colour development. After adding 1 M H2SO4 stop solution, optical density (OD) was measured immediately using a microplate reader set to 450 nm, and wavelength correction was set to 570 nm. Once an optimized linear standard curve was achieved, sample concentrations were analysed in triplicate with a corresponding standard curve for comparison and graphed in ng/ml.

CXCL12 western blotting

To assess the potential proteolytic effect of MMP-9 on CXCL12 protein, CXCL12 Western blotting was employed to analyse the in vitro incubation reaction products of recombinant MMP-9 on CXCL12. Recombinant CXCL12 (50 ng) (R&D systems) was incubated with or without recombinant MMP-9 protein (100 ng) (911-MP; R&D Systems) for 8 h at 37 °C (Jin et al. 2008), and the reaction was terminated by the addition of SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis loading buffer (Athanassiadou et al. 2006). Samples were run on a 15% polyacrylamide gel alongside with a prestained protein ladder (10748010 BenchMark™; Invitrogen Pty Ltd), transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Pall Life Sciences, Melbourne, Vic., Australia) using the semi-dry method (Bio-Rad Laboratories Pty Ltd, Sydney, NSW, Australia). After blocking with 5% non-fat milk powder for 2 h at 4 °C, membranes were incubated with 2 μg/ml of anti-human/mouse CXCL12/SDF-1 antibody (MAB350; R&D Systems) overnight at 4 °C. Membranes were then incubated with biotinylated rabbit anti-mouse secondary antibody (Dako, Sydney, NSW, Australia) (1:600) for 1 h and followed by strepdavidin-HRP (R&D systems) (1:200) for 30 min. Enzyme chemiluminescence was read subsequent to incubation of the membrane with appropriate substrate solution.

Statistical analyses

Standard one-way anova with Tukey posttest was performed using graphpad Prism (5.01 for Windows; GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Significance was achieved when P < 0.05, where different superscript letters in figures, denote mean values being significantly different from each other.

Results

Changes in bone marrow cell density and haematopoietic precursors

Consistent with the clear reduction in BM cellularity most notably on day 6 after the first MTX dosing (Figure 1a,b), viable cell densities of BM aspirates as assessed by trypan blue dye exclusion were found to be significantly decreased on day 6 (6.06 × 106 cells/ml), day 9 (18.26 × 106 cells/ml) and day 10 (22.01 × 106 cells/ml), when compared to control (45.89 × 106 cells/ml). By day 14, the viable cell density returned close to control (36.24 × 106 cells/ml) (Figure 1c).

Figure 1.

Methotrexate (MTX)-induced changes to bone marrow (BM) cellularity and recovery following short-term MTX treatment. (a) H&E-stained histology section of tibial diaphyseal BM in a control rat. (b) Histology of H&E-stained section from a rat 6 days after initial dose of 0.75 mg/kg MTX. Scale bar 100 μM. (c) Total BM cellularity expressed as total mononuclear cells × 106 cells/ml. (d) Ex vivo granulocyte/macrophage-lineage colony formation with BM cells isolated from rats over the MTX time-course. Different superscript letters denote means significantly different from each other P < 0.05.

Despite evidence of reduced HSC cellularity after MTX treatment, a CFU-GM assay of BM aspirates indicated that on day 6, there was an increase in colony formation of granulocyte and macrophage progenitor cell lineage on this day 6 time-point, although CFU-GM formation at all other time-points remained at the control level (Figure 1d). This suggests that among the early precursor cells and those that remain unaffected by chemotherapy ablation in the BM on day 6, a greater portion of these cells have the capacity to differentiate along the granulocyte/macrophage lineage. This may be a potential mechanism to enrich the pools of HSC precursors for achieving BM recovery, a possibility that requires further investigation in the present model.

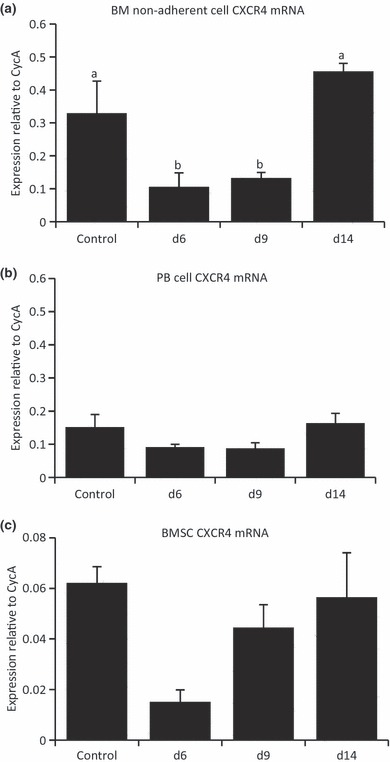

Reduced CXCR4 expression correlates with depleted BM cellularity

As previous studies have established the notion that antagonizing CXCR4 or posttranslational cleavage of CXCR4 results in mobilization of progenitor cells to the circulation (Nie et al. 2008), in the current study, we assessed the mRNA expression of CXCR4 in BM non-adherent HSC cells, PB cells and BM stromal cells. Although it has also been illustrated to be expressed on a small population of stromal stem cells, CXCR4 is expressed predominantly on cells of the HSC lineage. There was an observed reduction in CXCR4 gene expression in the BM non-adherent cell fraction on day 6 and day 9 (Figure 2a), correlating with the periods of reduced BM cellularity. This suggests that potential deregulation of CXCL12/CXCR4 signalling may occur in this MTX chemotherapy-induced stress, partially associated with the reduced HSC cell density observed in the BM cavity. However, CXCR4 mRNA expression remained relatively unchanged in both PB and BM stromal cell populations on all time-points (Figure 2b–c).

Figure 2.

Changes in receptor CXCR4 mRNA expression over the methotrexate chemotherapy-induced damage/recovery time-course. Quantitative RT-PCR relative gene expression analysis relative to endogenous control Cyclophilin A with RNA isolated from bone marrow (BM) non-adherent cells (a), whole peripheral blood specimens (b) and BM stromal cells (c). Different superscript letters denote means significantly different from each other P < 0.05.

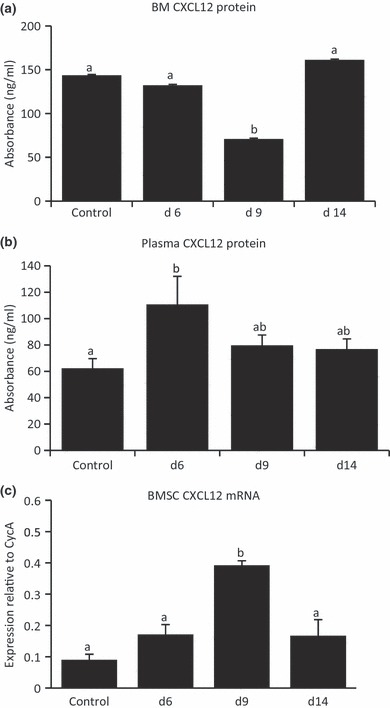

Changes in CXCL12 expression associated with reduced BM cellularity

As the well-characterized chemotactic function of CXCL12 (mediated by the G-protein-coupled receptor CXCR4) is involved in G-CSF, stress and chemotherapy-induced progenitor cell mobilization, we investigated effects of MTX treatment on BM and PB plasma CXCL12 protein levels. Following MTX treatment, CXCL12 protein expression in the BM supernatant was found to be reduced significantly on day 9 and returned to control levels by day 14 (Figure 3a). In contrast, CXCL12 protein expression in the blood plasma was found to increase significantly on day 6 when compared to control samples and remained unchanged at other time-points following MTX treatment (Figure 3b). Despite this increase in CXCL12 protein on day 6, BM concentrations were still greater over the time-course.

Figure 3.

Methotrexate (MTX) chemotherapy-induced changes in chemokine CXCL12 protein and mRNA expression. CXCL12 protein levels (ng/ml) were determined by ELISA in bone marrow (BM) supernatant (a) and in peripheral blood plasma (b) from MTX-treated and untreated control rats. (c) Quantitative RT-PCR relative gene expression analysis of CXCL12 in RNA isolated from BM stromal cells from normal and MTX-treated rats at different time-points. Different superscript letters denote means significantly different from each other P < 0.05.

To further investigate the source of MTX-induced changes to CXCL12 regulation, we assessed CXCL12 mRNA expression in cultured BMSCs and non-adherent cells from MTX-treated rats. On day 9, CXCL12 gene expression was found to be significantly greater than control levels and declined again by day 14 (Figure 3c), suggesting BMSCs may upregulate their expression of CXCL12 to allow progenitor cells homing back to the BM microenvironment to re-establish the depleted BM cavity. CXCL12 mRNA expression in the cultured non-adherent cell population was found to be very low to undetectable (data not shown).

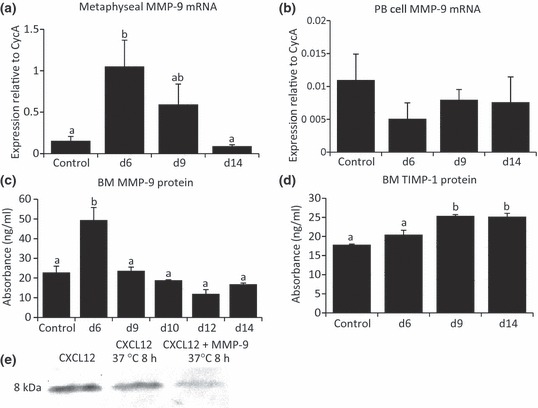

Increased MMP-9 expression associated with reduced CXCL12 protein concentrations

Previous studies have indicated that MMP-9 degrades CXCL12, disrupting the CXCL12/CXCR4 interaction when assessed both in vitro and in vivo under conditions of G-CSF-induced HSC progenitor mobilization (Carion et al. 2003; Levesque et al. 2003; Jin et al. 2008). In view of the reduction in CXCL12 protein expression yet an increase in gene expression on day 9 following MTX-induced damage, we hypothesized that this could be because of cleavage of CXCL12 protein by MMP-9 and hence degradation. As an initial step to investigate this possibility, metaphyseal bone that contains all bone and marrow cell populations rather than specifically stromal or HSC cell populations was assessed for MMP-9 mRNA expression on day 6, day 9 and day 14 after MTX treatment as compared to normal control. On day 6, MMP-9 gene expression was found to be significantly increased, which returned to control levels by day 14 (Figure 4a). Consistent with the increased CXCL12 protein in the blood plasma on day 6 and the potential of MMP-9 in the regulation of CXCL12 protein levels, there was a decrease in MMP-9 mRNA expression in PB cells on day 6 (P > 0.05 compared to normal control, Figure 4b).

Figure 4.

Methotrexate (MTX) chemotherapy-induced changes in MMP-9 and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 (TIMP-1) expression and activity of MMP-9 in degrading recombinant CXCL12 in vitro. Quantitative RT-PCR relative gene expression analysis of MMP-9 in RNA isolated from whole metaphyseal bone (a) and from whole peripheral blood specimens (b). Protein levels (ng/ml) over the MTX time-course were determined by ELISA for MMP-9 (c) and for the naturally occurring MMP-9 inhibitor TIMP-1 (d) in bone marrow supernatant from control and days 6, 9 and 14 after MTX treatment. (e) Assessment by Western blot showing CXCL12 recombinant protein is partially degraded after in vitro incubation with MMP-9 recombinant protein for 8 h. Different superscript letters denote means significantly different from each other P < 0.05.

Consistent with the observed increase in MMP-9 gene expression on day 6 in metaphyseal bone, MMP-9 protein expression in BM supernatant specimens was found to be substantially increased on day 6 (P < 0.001 when compared to control), which returned to basal levels on day 9, 10, 12 and 14 following MTX treatment (Figure 4c). On the other hand, there were no changes in MMP-9 inhibitor TIMP-1 protein expression in day 6 marrow samples when compared to control (Figure 4d). There was however an apparent increase in TIMP-1 protein expression on day 9 and 14 when compared to control (P < 0.001) and day 6 (P < 0.01), potentially associated with inhibition of MMPs during the recovery after MTX-induced changes to bone and BM.

Previously, in vitro studies have shown that MMP-9 present in mobilized BM plasma completely abolished the presence of recombinant CXCL12 protein, which can be blocked by an anti-MMP-9 monoclonal antibody (Jin et al. 2008). In the current study, to elucidate whether MMP-9 has a direct effect on CXCL12 protein level, in vitro incubation of MMP-9 and CXCL12 revealed that the presence of recombinant MMP-9 protein appeared to reduce the amount of CXCL12 protein present following an 8-h incubation period as revealed by CXCL12 Western blotting analysis. This suggests that increased MMP-9 expression observed following MTX treatment may be associated with the reduction in CXCL12 protein expression (Figure 4e).

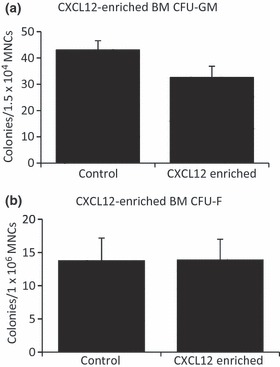

CXCL12 does not appear to enhance cell differentiation

In view of the deregulated expression of the CXCL12/CXCR4 axis after MTX chemotherapy observed in our model, the potential role of CXCL12 in directly regulating HSC or stromal precursor growth/differentiation in ex vivo culture was assessed. Addition of recombinant CXCL12 to the growth medium of MTX-untreated control BMMNCs did not obviously affect the formation of CFU-GM or CFU-F total colonies or alkaline phosphatase-stained colonies representing osteogenic differentiation potential when compared to BMMNCs grown in unsupplemented medium (Figure 5). This suggests that CXCL12 does not directly act as a promoting factor for the HSC or stromal progenitor cell growth or osteogenic differentiation.

Figure 5.

Effects of exogenous CXCL12 protein on differentiation potential of bone marrow cells isolated from normal rats. (a) Ex vivo granulocyte/macrophage-lineage colony formation assay; (b) Ex vivo colony formation-fibroblast assay.

Discussion

Cancer chemotherapy treatment has a myriad of detrimental side effects, including myelosuppression within the BM (Das et al. 2003, 2008; Meng et al. 2003; Abd-Allah et al. 2005), decreased bone formation and increased bone resorption, resulting in osteopenia or osteoporosis (Xian et al. 2007, 2008; Fan et al. 2009). Intrinsic recovery of a damaged BM environment is enabled by the maintenance of a quiescent stem cell pool residing at the endosteum, whereby these cells are induced into the cell cycle to allow re-establishment of a depleted marrow cavity. One important signalling pair that maintains quiescent stem cell populations and their regulated release into the cell cycle is the CXCL12/CXCR4 chemotactic axis (Georgiou et al. 2010). This study used a rat chemotherapy model with the commonly used antimetabolite MTX to gain a better understanding of the actions of chemokine CXCL12 and receptor CXCR4 in the damage and ensuing recovery of the BM microenvironment following chemotherapy treatment. Herein, we illustrated that there appears to be deregulation of both CXCL12 and CXCR4 expression, which is associated with reduced BM cellularity following MTX treatment. Furthermore, the reduced CXCL12 protein level following MTX damage may potentially be associated with MTX chemotherapy-induced MMP-9 expression. In addition, despite an overall reduction in total BM cell viability on day 6 and day 9, there is an increase in HSC differentiation potential.

Methotrexate treatment was observed to cause an overall reduction in BM cellularity, particularly on days 6 and 9, with a return to control density by day 14. During the damage and recovery time-course following MTX chemotherapy, there appears to be deregulation of the CXCL12/CXCR4 axis. Consistent with the reduced HSC cellularity, HSC cell CXCR4 mRNA expression was reduced in the BM non-adherent cell fraction on day 6 and day 9. This suggests that deregulation of CXCR4 is occurring during MTX chemotherapy-induced stress, potentially associated with the reduced HSC cell density observed in the BM cavity as a result of the disruption of CXCL12/CXCR4 interaction (Semerad et al. 2005; Christopher et al. 2009). In addition to the complex role of the CXCL12/CXCR4 signalling pathway under steady-state and damaged conditions, cancer-induced microenvironment changes can cause upregulation of CXCR4 by cancerous cells, resulting in cancer cell migration to tissues with high CXCL12 protein expression, notably bone and breast (Mohle et al. 1998; Muller et al. 2001; Hartmann et al. 2005; Manu et al. 2011). Interestingly, chronic treatment with 5-FU or MTX has been investigated for its direct influence on MTX-resistant human colon cancer cell line migration and CXCR4 expression, whereby MTX resistance was positively correlated with invasiveness and high expression of CXCR4, with CXCL12/CXCR4 signalling thought to be partly responsible for drug-resistant tumour formation (Dessein et al. 2010; Margolin et al. 2011). These previous studies and our own findings suggest that CXCL12/CXCR4 signalling is important in mobilization of not only hematopoietic cells in injury recovery but cancer cells in metastasis.

However, the focus of the present investigation was the potential importance of the CXCL12/CXCR4 signalling pathway in the regulation of BM cell populations following chemotherapy treatment alone. In this respect, potentially associated with the reduced BM cellularity observed following MTX treatment, CXCL12 protein expression in both BM and blood plasma was found to be altered over the time-course. While BM CXCL12 protein was reduced on day 9 and increased in the blood plasma on day 6, its expression levels in BM were still maintained at a concentration higher than the plasma levels. The present observation of an increase in CXCL12 protein in the PB plasma on day 6 is inconsistent with clinical findings in patients on myeloablative therapies displaying lower levels of plasma CXCL12 protein (Gazitt & Liu 2001; Cecyn et al. 2009). On the other hand, a previous report has also shown a positive correlation between an increased level of PB plasma CXCL12 protein and the number of circulating endothelial progenitor cells (Smythe et al. 2008). As endothelial and stromal cells are responsible for CXCL12 expression, it is possible that a portion of the mobilized cell population is expressing CXCL12 on day 6, which could partially be responsible for the observed increase. However, further investigations are required to elucidate the cause and effect of an altered level of PB plasma CXCL12 protein on day 6. However, despite the reduction in BM CXCL12 protein expression, BMSC CXCL12 mRNA was increased on day 9, suggesting an alternate mechanism of regulating CXCL12 protein expression under the MTX-induced damage conditions. These findings in the current MTX chemotherapy model suggest deregulation of the CXCL12/CXCR4 axis in mediating the reduced cellularity after MTX chemotherapy and complement the previously demonstrated role of CXCL12 in G-CSF-induced mobilization of HSC progenitor cells out of the BM microenvironment (Siena et al. 1989; Fleming et al. 1993; Petit et al. 2002; Jin et al. 2008).

Further investigations are required to elucidate the importance and underlying mechanisms of deregulated CXCL12 in the present MTX chemotherapy model. However, the reduction in CXCL12 protein, yet increased mRNA expression observed in the BM, prompted our investigations into the possibility of degradation or cleavage of CXCL12 protein in the BM. Therefore, we sought to investigate the potential involvement or role in our MTX chemotherapy model of MMP-9, which has been illustrated previously to directly cleave CXCL12 at its N-terminus (McQuibban et al. 2001). In our MTX chemotherapy model, MMP-9 expression was found significantly increased on day 6 after MTX treatment on both the mRNA and protein levels in the BM. In addition, our in vitro studies have demonstrated direct degrading potential of MMP-9 recombinant protein on CXCL12. These results suggest that the increase in MMP-9 protein expression in BM specimens after MTX chemotherapy may be playing a role in the transient changes in CXCL12 protein following MTX on day 9; however, its role in cleavage of CXCL12 causing degradation cannot be elucidated until further investigated in the MTX model in vivo. Interestingly, in the present study, TIMP-1 protein levels were found increased on days 9 and 14, suggesting that an increased level of TIMP-1 may be involved in limiting action of MMPs during bone/BM recovery after MTX treatment. Further investigations into the association between MTX-induced BM damage and MMP-9 upregulation/TIMP-1 action are required, particularly the relationship between increased osteoclast activity under stress-induced conditions potentially regulating MMP-9 protein expression (Levesque et al. 2004; Zannettino et al. 2005; Kollet et al. 2006; Gronthos & Zannettino 2007). In addition, despite a clear reduction in BM cellularity at the histological level, our in vitro HSC progenitor cell differentiation assays showed a greater potential for CFU-GM differentiation on day 6. While this may be a recovery mechanism in place to re-establish the marrow environment following damage, further investigations into this increased differentiation capacity and the potential role of the CXCL12/CXCR4 axis in BM progenitor cell recovery are essential.

In summary, our data illustrate that there are changes in gene and protein expression of CXCL12 and CXCR4 following MTX chemotherapy. Associated with the observed reduction in BM cellularity is decreased CXCR4 expression by HSC cells and a reduction in CXCL12 protein in the BM. Furthermore, consistent with previous studies showing MMP-9 can degrade CXCL12, which was also observed in the current study, we observed an increase in MMP-9 expression in the bone and BM following MTX chemotherapy and confirmed its capacity to directly degrade CXCL12 protein. These findings suggest that MTX chemotherapy transiently alters BM cellularity and composition and that such reduced cellularity may be associated with deregulated CXCL12/CXCR4 chemotactic signalling. Further studies are required to elucidate whether and how MMP-9 is involved in CXCL12 cleavage in vivo after MTX chemotherapy and the potential role of MMP-9 in deregulation of the CXCL12/CXCR4 axis and in the damage and re-establishment of the BM microenvironment associated with MTX chemotherapy. Defining the mechanisms governing regulation of the CXCL12/CXCR4 axis during chemotherapy-induced damage and recovery may reveal potential targets for maintaining marrow cell populations and preventing damage. Such knowledge may in turn improve the survival rate and quality of life of cancer survivors in the long term, by reducing BM toxicity and/or enhancing recovery and maintaining steady-state bone remodelling and turnover.

Acknowledgments

This project was funded in part by Bone Growth Foundation (Australia), Women’s and Children’s Hospital Foundation, Channel-7 Children Research Foundation and NHMRC Australia. KRG was a recipient of University of Adelaide Faculty of Science PhD Scholarship. CJX is a senior fellow of NHMRC Australia.

References

- Abd-Allah AR, Al-Majed AA, Al-Yahya AA, Fouda SI, Al-Shabana OA. L-Carnitine halts apoptosis and myelosuppression induced by carboplatin in rat bone marrow cell cultures (BMC) Arch. Toxicol. 2005;79:406–413. doi: 10.1007/s00204-004-0643-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed SF, Wallace WH, Kelnar CJ. An anthropometric study of children during intensive chemotherapy for acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Horm. Res. 1997;48:178–183. doi: 10.1159/000185510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Athanassiadou F, Tragiannidis A, Rousso I, et al. Bone mineral density in survivors of childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Turk. J. Pediatr. 2006;48:101–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balabanian K, Lagane B, Infantino S, et al. The chemokine SDF-1/CXCL12 binds to and signals through the orphan receptor RDC1 in T lymphocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:35760–35766. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508234200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banfi A, Podesta M, Fazzuoli L, et al. High-dose chemotherapy shows a dose-dependent toxicity to bone marrow progenitors: a mechanism for post-bone marrow transplantation osteopenia. Cancer. 2001;92:2419–2428. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20011101)92:9<2419::aid-cncr1591>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Ishay Z, Barak V. Bone marrow stromal dysfunction in mice administered cytosine arabinoside. Eur. J. Haematol. 2001;66:230–237. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0609.2001.066004230.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broxmeyer HE, Orschell CM, Clapp DW, et al. Rapid mobilization of murine and human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells with AMD3100, a CXCR4 antagonist. J. Exp. Med. 2005;201:1307–1318. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns JM, Summers BC, Wang Y, et al. A novel chemokine receptor for SDF-1 and I-TAC involved in cell survival, cell adhesion, and tumor development. J. Exp. Med. 2006;203:2201–2213. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carion A, Benboubker L, Herault O, et al. Stromal-derived factor 1 and matrix metalloproteinase 9 levels in bone marrow and peripheral blood of patients mobilized by granulocyte colony-stimulating factor and chemotherapy. Relationship with mobilizing capacity of haematopoietic progenitor cells. Br. J. Haematol. 2003;122:918–926. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cecyn KZ, Schimieguel DM, Kimura EY, Yamamoto M, Oliveira JS. Plasma levels of FL and SDF-1 and expression of FLT-3 and CXCR4 on CD34 + cells assessed pre and post hematopoietic stem cell mobilization in patients with hematologic malignancies and in healthy donors. Transfus. Apher. Sci. 2009;40:159–167. doi: 10.1016/j.transci.2009.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christopher MJ, Liu F, Hilton MJ, Long F, Link DC. Suppression of CXCL12 production by bone marrow osteoblasts is a common and critical pathway for cytokine-induced mobilization. Blood. 2009;114:1331–1339. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-184754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung R, Foster BK, Zannettino AC, Xian CJ. Potential roles of growth factor PDGF-BB in the bony repair of injured growth plate. Bone. 2009;44:878–885. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.01.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das B, Yeger H, Baruchel H, Freedman MH, Koren G, Baruchel S. In vitro cytoprotective activity of squalene on a bone marrow versus neuroblastoma model of cisplatin-induced toxicity. implications in cancer chemotherapy. Eur. J. Cancer. 2003;39:2556–2565. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2003.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das B, Antoon R, Tsuchida R, et al. Squalene selectively protects mouse bone marrow progenitors against cisplatin and carboplatin-induced cytotoxicity in vivo without protecting tumor growth. Neoplasia. 2008;10:1105–1119. doi: 10.1593/neo.08466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies J, Evans B, Jenney M, Gregory J. In vitro effects of chemotherapeutic agents on human osteoblast-like cells. Calcif. Tissue Int. 2002a;70:408–415. doi: 10.1007/s002230020039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies J, Evans B, Jenney M, Gregory J. In vitro effects of combination chemotherapy on osteoblasts: implications for osteopenia in childhood malignancy. Bone. 2002b;31:319–326. doi: 10.1016/s8756-3282(02)00822-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgado MB, Clark-Lewis I, Loetscher P, et al. Rapid inactivation of stromal cell-derived factor-1 by cathepsin G associated with lymphocytes. Eur. J. Immunol. 2001;31:699–707. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200103)31:3<699::aid-immu699>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dessein AF, Stechly L, Jonckheere N, et al. Autocrine induction of invasive and metastatic phenotypes by the MIF-CXCR4 axis in drug-resistant human colon cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2010;70:4644–4654. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devine SM, Vij R, Rettig M, et al. Rapid mobilization of functional donor hematopoietic cells without G-CSF using AMD3100, an antagonist of the CXCR4/SDF-1 interaction. Blood. 2008;112:990–998. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-130179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan C, Cool JC, Scherer MA, et al. Damaging effects of chronic low-dose methotrexate usage on primary bone formation in young rats and potential protective effects of folinic acid supplementary treatment. Bone. 2009;44:61–70. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2008.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming WH, Alpern EJ, Uchida N, Ikuta K, Weissman IL. Steel factor influences the distribution and activity of murine hematopoietic stem cells in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 1993;90:3760–3764. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedlaender G, Tross R, Doganis A, Kirkwood J, Baron R. Effects of chemotherapeutic agents on bone. J. Bone Joint Surg. Am. 1984;66:602–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazitt Y, Liu Q. Plasma levels of SDF-1 and expression of SDF-1 receptor on CD34 + cells in mobilized peripheral blood of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma patients. Stem Cells. 2001;19:37–45. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.19-1-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgiou KR, Foster BK, Xian CJ. Damage and recovery of the bone marrow microenvironment induced by cancer chemotherapy - potential regulatory role of chemokine CXCL12/receptor CXCR4 signalling. Curr. Mol. Med. 2010;10:440–453. doi: 10.2174/156652410791608243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgiou K, Scherer M, Fan C, et al. Methotrexate chemotherapy reduces osteogenesis but increases adipogenic potential in the bone marrow. J. Cell. Physiol. 2011 doi: 10.1002/jcp.22807. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gronthos S, Zannettino AC. The role of the chemokine CXCL12 in osteoclastogenesis. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2007;18:108–113. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddy TB, Mosher RB, Reaman GH. Osteoporosis in survivors of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Oncologist. 2001;6:278–285. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.6-3-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halton JM, Atkinson SA, Fraher L, et al. Altered mineral metabolism and bone mass in children during treatment for acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J. Bone Miner. Res. 1996;11:1774–1783. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650111122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han W, Yu Y, Liu X. Local signals in stem cell-based bone marrow regeneration. Cell Res. 2006;16:189–195. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7310026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann TN, Burger JA, Glodek A, Fujii N, Burger M. CXCR4 chemokine receptor and integrin signaling co-operate in mediating adhesion and chemoresistance in small cell lung cancer (SCLC) cells. Oncogene. 2005;24:4462–4471. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattori K, Heissig B, Tashiro K, et al. Plasma elevation of stromal cell-derived factor-1 induces mobilization of mature and immature hematopoietic progenitor and stem cells. Blood. 2001;97:3354–3360. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.11.3354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin F, Zhai Q, Qiu L, et al. Degradation of BM SDF-1 by MMP-9: the role in G-CSF-induced hematopoietic stem/progenitor cell mobilization. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2008;42:581–588. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2008.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung Y, Wang J, Schneider A, et al. Regulation of SDF-1 (CXCL12) production by osteoblasts; a possible mechanism for stem cell homing. Bone. 2006;38:497–508. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2005.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiefer T, Kruger WH, Montemurro M, et al. Mobilization of hemopoietic stem cells with high-dose methotrexate plus granulocyte-colony-stimulating factor in patients with primary central nervous system lymphoma. Transfusion. 2008;48:2624–2628. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2008.01927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollet O, Dar A, Shivtiel S, et al. Osteoclasts degrade endosteal components and promote mobilization of hematopoietic progenitor cells. Nat. Med. 2006;12:657–664. doi: 10.1038/nm1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque JP, Takamatsu Y, Nilsson SK, Haylock DN, Simmons PJ. Vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (CD106) is cleaved by neutrophil proteases in the bone marrow following hematopoietic progenitor cell mobilization by granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Blood. 2001;98:1289–1297. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.5.1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque JP, Hendy J, Takamatsu Y, Williams B, Winkler IG, Simmons PJ. Mobilization by either cyclophosphamide or granulocyte colony-stimulating factor transforms the bone marrow into a highly proteolytic environment. Exp. Hematol. 2002;30:440–449. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(02)00788-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque JP, Hendy J, Takamatsu Y, Simmons PJ, Bendall LJ. Disruption of the CXCR4/CXCL12 chemotactic interaction during hematopoietic stem cell mobilization induced by GCSF or cyclophosphamide. J. Clin. Invest. 2003;111:187–196. doi: 10.1172/JCI15994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque JP, Liu F, Simmons PJ, et al. Characterization of hematopoietic progenitor mobilization in protease-deficient mice. Blood. 2004;104:65–72. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Law HK, Lau YL, Chan GC. Differential damage and recovery of human mesenchymal stem cells after exposure to chemotherapeutic agents. Br. J. Haematol. 2004;127:326–334. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.05200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma ZY, Qian JM, Rui XH, et al. Inhibition of matrix metalloproteinase-9 attenuates acute small-for-size liver graft injury in rats. Am. J. Transplant. 2010;10:784–795. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2009.02993.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manu KA, Shanmugam MK, Rajendran P, et al. Plumbagin inhibits invasion and migration of breast and gastric cancer cells by downregulating the expression of chemokine receptor CXCR4. Mol. Cancer. 2011;10:107. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-10-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margolin DA, Silinsky J, Grimes C, et al. Lymph node stromal cells enhance drug-resistant colon cancer cell tumor formation through SDF-1alpha/CXCR4 paracrine signaling. Neoplasia. 2011;13:874–886. doi: 10.1593/neo.11324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuibban GA, Butler GS, Gong JH, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase activity inactivates the CXC chemokine stromal cell-derived factor-1. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:43503–43508. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107736200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng A, Wang Y, Brown SA, Van Zant G, Zhou D. Ionizing radiation and busulfan inhibit murine bone marrow cell hematopoietic function via apoptosis-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Exp. Hematol. 2003;31:1348–1356. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2003.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohle R, Bautz F, Rafii S, Moore MA, Brugger W, Kanz L. The chemokine receptor CXCR-4 is expressed on CD34 + hematopoietic progenitors and leukemic cells and mediates transendothelial migration induced by stromal cell-derived factor-1. Blood. 1998;91:4523–4530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller A, Homey B, Soto H, et al. Involvement of chemokine receptors in breast cancer metastasis. Nature. 2001;410:50–56. doi: 10.1038/35065016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy G, Willenbrock F, Crabbe T, et al. Regulation of matrix metalloproteinase activity. Ann. N Y Acad. Sci. 1994;732:31–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb24722.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagasawa T. Role of chemokine SDF-1/PBSF and its receptor CXCR4 in blood vessel development. Ann. N Y Acad. Sci. 2001;947:112–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03933.x. discussion 115-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagasawa T, Hirota S, Tachibana K, et al. Defects of B-cell lymphopoiesis and bone-marrow myelopoiesis in mice lacking the CXC chemokine PBSF/SDF-1. Nature. 1996;382:635–638. doi: 10.1038/382635a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nie Y, Han YC, Zou YR. CXCR4 is required for the quiescence of primitive hematopoietic cells. J. Exp. Med. 2008;205:777–783. doi: 10.1084/jem.20072513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petit I, Szyper-Kravitz M, Nagler A, et al. G-CSF induces stem cell mobilization by decreasing bone marrow SDF-1 and upregulating CXCR4. Nat. Immunol. 2002;3:687–694. doi: 10.1038/ni813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall TD, Weissman IL. Phenotypic and functional changes induced at the clonal level in hematopoietic stem cells after 5-fluorouracil treatment. Blood. 1997;89:3596–3606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ries C, Loher F, Zang C, Ismair MG, Petrides PE. Matrix metalloproteinase production by bone marrow mononuclear cells from normal individuals and patients with acute and chronic myeloid leukemia or myelodysplastic syndromes. Clin. Cancer Res. 1999;5:1115–1124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schriock EA, Schell MJ, Carter M, Hustu O, Ochs JJ. Abnormal growth patterns and adult short stature in 115 long-term survivors of childhood leukemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 1991;9:400–405. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1991.9.3.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semerad CL, Christopher MJ, Liu F, et al. G-CSF potently inhibits osteoblast activity and CXCL12 mRNA expression in the bone marrow. Blood. 2005;106:3020–3027. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-01-0272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siena S, Bregni M, Brando B, Ravagnani F, Bonadonna G, Gianni AM. Circulation of CD34 + hematopoietic stem cells in the peripheral blood of high-dose cyclophosphamide-treated patients: enhancement by intravenous recombinant human granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Blood. 1989;74:1905–1914. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sierro F, Biben C, Martinez-Munoz L, et al. Disrupted cardiac development but normal hematopoiesis in mice deficient in the second CXCL12/SDF-1 receptor, CXCR7. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2007;104:14759–14764. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702229104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smythe J, Fox A, Fisher N, Frith E, Harris AL, Watt SM. Measuring angiogenic cytokines, circulating endothelial cells, and endothelial progenitor cells in peripheral blood and cord blood: VEGF and CXCL12 correlate with the number of circulating endothelial progenitor cells in peripheral blood. Tissue Eng Part C Methods. 2008;14:59–67. doi: 10.1089/tec.2007.0251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thelen M, Thelen S. CXCR7, CXCR4 and CXCL12: an eccentric trio? J. Neuroimmunol. 2008;198:9–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2008.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright D, Bowman E, Wagers A, Butcher E, Weissman I. Hematopoietic stem cells are uniquely selective in their migratory response to chemokines. J. Exp. Med. 2002;195:1145–1154. doi: 10.1084/jem.20011284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xian C, Cool J, Pyragius T, Foster B. Damage and recovery of the bone growth mechanism in young rats following 5-fluorouracil acute chemotherapy. J. Cell. Biochem. 2006;99:1688–1704. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xian CJ, Cool JC, Scherer MA, et al. Cellular mechanisms for methotrexate chemotherapy-induced bone growth defects. Bone. 2007;41:842–850. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xian CJ, Cool JC, Scherer MA, Fan C, Foster BK. Folinic acid attenuates methotrexate chemotherapy-induced damages on bone growth mechanisms and pools of bone marrow stromal cells. J. Cell. Physiol. 2008;214:777–785. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zannettino AC, Farrugia AN, Kortesidis A, et al. Elevated serum levels of stromal-derived factor-1alpha are associated with increased osteoclast activity and osteolytic bone disease in multiple myeloma patients. Cancer Res. 2005;65:1700–1709. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]