Summary

Bone marrow (BM) cells may transdifferentiate into circulating fibrocytes and myofibroblasts in organ fibrosis. In this study, we investigated the contribution and functional roles of BM-derived cells in murine cerulein-induced pancreatic fibrosis. C57/BL6 female mice wild-type (WT) or Col 1α1r/r male BM transplant, received supraphysiological doses of cerulein to induce pancreatic fibrosis. The CD45+Col 1+ fibrocytes isolated from peripheral blood (PB) and pancreatic tissue were examined by in situ hybridization for Y chromosome detection. The number of BM-derived myofibroblasts, the degree of Sirius red staining and the levels of Col 1α1 mRNA were quantified. The Y chromosome was detected in the nuclei of PB CD45+Col 1+ fibrocytes, confirming that circulating fibrocytes can be derived from BM. Co-expression of α-smooth muscle actin illustrated that fibrocytes can differentiate into myofibroblasts. The number of BM-derived myofibroblasts, degree of collagen deposition and pro-collagen I mRNA expression were higher in the mice that received Col 1α1r/r BM, (cells that produce mutated, collagenase-resistant collagen) compared to WT BM, indicating that the genotype of BM cells can alter the degree of pancreatic fibrosis. Our data indicate that CD45+Col 1+ fibrocytes in the PB can be BM-derived, functionally contributing to cerulein-induced pancreatic fibrosis in mice by differentiating into myofibroblasts.

Keywords: bone marrow, fibrocytes, fibrosis, myofibroblasts, pancreatitis

Pancreatic fibrosis often results from repeated overt or silent episodes of acute pancreatitis, causing the permanent destruction of the pancreas resulting in pancreatic exocrine insufficiency and/or endocrine failure (Andersen 2007; Behrman & Fowler 2007). Clinically, most patients suffer from chronic pain, maldigestion and diabetes. Fibrosis is not only associated with a high morbidity when biliary or pancreatic ductal obstruction occurs secondary to fibrotic stenosis, but it is also a well-described risk factor for the development of pancreatic adenocarcinoma (Lowenfels et al. 1993; Malka et al. 2002; Witt et al. 2007).

Fibrocytes are defined as cells that produce collagen 1 (Col 1) and express the leucocyte common antigen (CD45), the haematopoietic stem cell marker (CD34) and myeloid antigens (CD11b, CD13) (Bellini & Mattoli 2007; Reilkoff et al. 2011). They have been demonstrated to participate in many human fibrotic diseases including hypertrophic scars, systemic fibroses, atherosclerosis and in pulmonary diseases characterized by repeated inflammation and repair such as asthma and interstitial pulmonary fibrosis. In these diseases, they produce both extracellular matrix (ECM) components and ECM degrading enzymes such as matrix metalloproteinase-9 (Chesney et al. 1998; Hartlapp et al. 2001; Pilling et al. 2003), as well as differentiating into myofibroblasts (Abe et al. 2001; Schmidt et al. 2003; Mori et al. 2005; Pilling et al. 2006).

In the pancreas, CD34-positive fibrocyte-like cells have been detected in tissue specimens from patients with chronic pancreatitis (Barth et al. 2002; Kuroda et al. 2004). The accumulation of these cells seems to be related to a parallel increase in the number of α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA)-positive myofibroblasts (Barth et al. 2002). It was thought that active myofibroblasts play an important role in pancreatic inflammation and fibrosis and are mainly derived from local residential pancreatic stellate cells (PaSCs) (Omary et al. 2007). However, several recent studies have provided evidence that bone marrow (BM)-derived precursors can also contribute to PaSCs and myofibroblasts in chronic pancreatitis (Marrache et al. 2008; Watanabe et al. 2009). Although the phenotype of these BM-derived precursors is not clear, it has been suggested that BM-derived myofibroblasts may develop from circulating fibrocytes (Direkze et al. 2003; Schmidt et al. 2003; Mori et al. 2005; Lin et al. 2008).

In this study, we test the hypothesis that CD45+ColI+ fibrocytes are derived from BM and can contribute to pancreatic fibrosis. Using a sex-mismatch BM transplantation and cerulein-induced pancreatitis mouse model, we demonstrate that circulating fibrocytes are derived from BM. Furthermore, fibrocytes can engraft into the pancreas from the peripheral circulation, contributing to pancreatic fibrosis in part by differentiating into myofibroblasts. Finally, we demonstrate that the transplantation of ColIα1r/r BM (cells that produce collagenase-resistant collagen) can affect the severity of pancreatic fibrosis in mice, suggesting BM-derived fibrogenic cells can modify organ fibrosis.

Material and methods

Experimental protocols

Induction of chronic pancreatic fibrosis

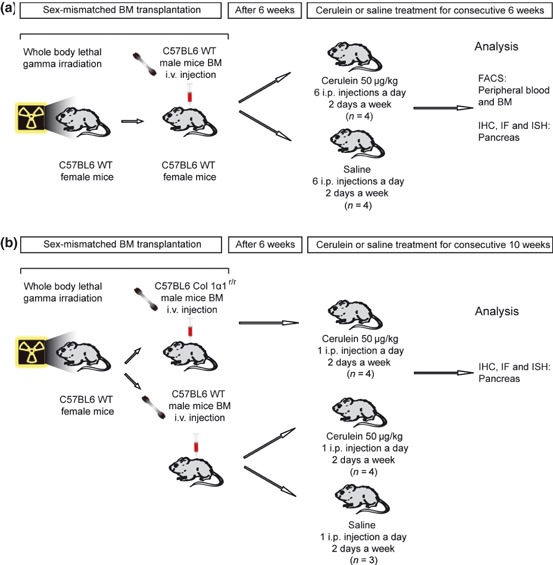

The procedures for animal experiments were performed under British Home Office procedural and ethical guidelines and were approved by our local (Cancer Research, UK) Animal Ethics Committee. The experimental protocols are shown in Figure 1(a). Six- to eight-week-old WT C57/BL6 female recipient mice (The Charles River Laboratory, Margate, Kent, UK) underwent whole-body lethal gamma irradiation with 10 Gy in a divided dose 4 h apart, to ablate their BM, followed immediately by tail vein injection of WT male whole BM (2 × 106 cells), resuspended in 0.1 ml sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) with 2% foetal calf serum (FCS). Six weeks after the BM transplantation, four mice were given six intraperitoneal injections of a cholecystokinin analogue, cerulein (Sigma-Aldrich, Poole, UK), at a dose of 50 μg/kg, at hourly intervals for 1 day to induce acute pancreatic inflammation. Pancreatic tissues were harvested at 24 h after the last injection. To induce chronic pancreatic fibrosis, four mice were given six intraperitoneal injections of cerulein (Sigma-Aldrich), at a dose of 50 μg/kg, at hourly intervals in a day, twice a week for six consecutive weeks. The mice in the control group (n = 4) received the same protocol but cerulein injections were replaced by saline. Blood, BM and pancreatic tissues were harvested at 48 h after the last injection.

Figure 1.

(a) The study design for detecting fibrocytes in peripheral blood, bone marrow (BM) and pancreas in severe cerulein-induced pancreatic fibrosis. (b) The study design for examining the functional role of Col 1α1r/r BM-derived cells in mild cerulein-induced pancreatic fibrosis.

Induction of mild pancreatic fibrosis for examining the functional role of BM

For the purpose of examining the functional role of BM-derived fibrogenic cells, we transplanted Col 1α1r/r male BM, whose cells carry a mutation that encodes amino acid substitutions in the alpha 1 chain of type 1 collagen (Wu et al. 1990; Liu et al. 1995) that prevents collagenase cleavage, into female WT mice. We also decreased the dose of cerulein injection, creating very mild fibrosis in the pancreas (Figure 1b), thus the effects on pancreatic fibrosis caused by Col 1α1r/r BM-derived fibrogenic cells could be more readily discerned. Six weeks after the BM transplantation, mice received an intraperitoneal injection of 50 μg/kg cerulein twice a week for up to 10 weeks. Groups of mice transplanted with BM from either WT or Col 1α1r/r male mice were killed after 10 weeks of injections of either cerulein or saline (WT, n = 4; Col 1α1r/r, n = 4; control, n = 3). Pancreatic tissues were harvested at 48 h after the last injection and fixed in 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde (PFA) in PBS for 16 h or zinc fixative (0.1 M Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 3 mM calcium acetate, 23 mM zinc acetate, 37 mM zinc chloride) for 12 h before being embedded in paraffin wax.

Fibrocyte analysis of peripheral blood

Peripheral blood mononuclear cell preparations

Terminal blood samples (0.7 ml) were taken by cardiac puncture into heparin-coated tubes. A volume of 0.2 ml of blood was aliquoted into separate 15-ml Falcon tubes (Scientific Laboratory Supplies Ltd, Nottingham, UK). Next, 1.8 ml of lysing solution (Becton-Dickinson, Bedford, MA, USA) was added to each tube, vortexed and left to incubate for 3 min in the dark. After incubation, 13 ml of PBS were added to each tube to dilute the lysing solution and centrifuged at 400 g for 4 min. The resultant supernatant was removed, and the pellet was resuspended in wash buffer (PBS/0.1% NaN3/1.0% FCS) for fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis.

CD45+Col 1+ fibrocyte isolation

1 × 106 cells resuspended in wash buffer were incubated for 30 min in the dark at 4 °C with a PE-conjugated monoclonal antibody against mouse CD45 (553081; BD Pharmingen, Oxford, UK). After washing twice, Aqua stain dye (L34957; Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) was added and incubated in the dark for 30 min at 4 °C. The cells were then fixed in 4% PFA for 20 min at 4 °C, and cell membranes permeablized by BD Perm/Wash buffer (554723; BD Pharmingen) for 15 min. After washing, the cells were incubated for 30 min in the dark at 4 °C with a rabbit anti-mouse collagen 1 antibody (AB765P; Millipore, Watford, UK). After washing twice, the cells were incubated with Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated goat anti-rabbit Ig (A21246; Invitrogen) for 30 min in the dark at 4 °C. After washing, the cells were resuspended in washing buffer and were sorted using a FACS Aria (Becton-Dickinson), following the instrument configuration and sorting procedure recommended by the manufacturer. The dead cells were excluded by positive staining with the Aqua stain dye. The FACS-isolated cells were resuspended in PBS and centrifuged onto glass slides at 500 g for 10 min using a Cyto-Tek centrifuge (Electron Microscopy Science, Hatfield, PA, USA). The sections were air-dried for 1 day and then were processed for in situ hybridization (ISH) for Y chromosome detection.

Immunohistochemical analyses

To identify fibrocytes in the pancreas, sections were double-immunostained with rat anti-mouse CD45 (550539; BD Pharmingen) and rabbit anti-mouse collagen 1 (AB765P; Millipore). A mouse monoclonal antibody against α-SMA (A-2547; Sigma-Aldrich) was used to detect myofibroblasts. Sections cut at 4 μm were dewaxed, incubated in 1.8% v/v hydrogen peroxide in methanol for 15 min to block endogenous peroxidases and then taken through graded alcohols to PBS. The sections were then incubated in 20% v/v acetic acid in methanol to block endogenous alkaline phosphatases.

Antigen retrieval treatment was performed by microwaving (700W) sections in BD Retrievagen A solution (550524; BD Pharmagen, Oxford, UK) for 10 min. To reduce non-specific background staining, sections were next preincubated with 1% bovine serum albumin (A4503; Sigma-Aldrich) for 30 min. For intracellular collagen 1 staining, the sections were incubated with 0.25% Triton-X 100 (T8787; Sigma-Aldrich) for 10 min.

Primary antibodies were used at dilutions of 1:50 for CD45, 1:100 for collagen I and 1:4000 for α-SMA. The secondary antibodies for CD45 were either biotinylated rabbit anti-rat immunoglobulin (BA-4000; Vector Laboratory, Orton Southgate, UK) at a 1:100 dilution or biotinylated goat anti-rat immunoglobulin (112-065-167; Jackson ImmunoResearch laboratory, Newmarket, UK) at a 1:250 dilution. The secondary antibodies for collagen 1 were either Alexa Fluor 350-conjugated donkey anti-rabbit immunoglobulin (A10039; Invitrogen) at 1:50 dilution or biotinylated swine anti-rabbit immunoglobulin at 1:500 dilution (E3053; Dako, Ely, UK). For α-SMA, the secondary antibody was either a Cy-5-conjugated goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin (81-6516; Zymed Laboratories, San Francisco, CA, USA) at a dilution of 1:50 or a biotinylated polyclonal rabbit anti-mouse immunoglobulin at a dilution of 1:300 (E0464; Dako). Tertiary layers of either alkaline phosphatase-conjugated streptavidin (D0396; Dako) at a 1:50 dilution for CD45 and α-SMA, or peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin (P0397; Dako) at a dilution of 1:500 for collagen 1 followed. Slides were developed in Vector red substrate (SK-5100; Vector Laboratory) for CD45 and α-SMA or DAB for collagen 1. Slides were counterstained lightly with haematoxylin, dehydrated and mounted in DPX-type mount.

In situ hybridization for Y chromosome detection

To identify the BM-derived fibrocytes and myofibroblasts, ISH for Y chromosome –specific sequences was performed, in combination with immunostaining for fibrocyte and myofibroblast markers.

Sections were cut at 4 μm and incubated in 1 M sodium thiocyanate (S7757; Sigma-Aldrich) for 10 min at 80 °C to improve access of probe to DNA. Following PBS washing, sections were digested in 0.4% w/v pepsin (P6887; Sigma-Aldrich) in 0.1 M hydrochloric acid for 4 min at 37 °C to improve further access of the Y chromosome probe. The duration of pepsin digestion depended on the extent of tissue fixation. The protease reaction was quenched in 0.2% w/v glycine (G4392; Sigma-Aldrich) in double-concentration PBS, and sections were then rinsed in PBS, postfixed in 4% w/v PFA (P6148; Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS, dehydrated through graded alcohols and lastly air-dried. A fluorescein isothiocyanate-labelled Y chromosome paint (1189-YMF-01; Cambio, Cambridge, UK) was used in the supplier’s hybridization mix. The probe mixture was added to the sections, sealed under glass with rubber cement, heated to 60 °C for 10 min and then incubated overnight at 37 °C in a humidified chamber.

The next day, all slides were washed in 0.5× standard saline citrate at 37 °C. For the direct detection of the Y chromosome, all sections following washing with PBS were cover-slipped with Vectashield Hard Set mount (H1400; Vector Laboratories).

Collagen staining

Picro-Sirius red (VWR International) staining was used for intrapancreatic collagen detection. Quantitative analysis of collagen deposition was performed by digitized image analysis with NIH-ImageJ software (Rangan & Tesch 2007). The total pancreatic tissue area was distinguished from the background according to a difference in light density. The total area of collagen (stained in red) was measured and expressed as a percentage of the total pancreatic surface.

RNA preparation and real-time PCR

The expression of mRNA for Col 1α1 and GAPDH in total RNA was determined by quantitative real-time PCR. Total RNA was extracted by an acid guanidinium thiocyanate–phenol–chloroform method from mice that received a BM transplant from either WT or Col 1α1r/r mice. First strand cDNA was synthesized from 2.5 μg of total cellular RNA with oligo (dT) primer and superscript II reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). All primers and probes were designed by Taqman Primer Express program, and quantification of mRNA was performed by the PE Applied Biosystems 7700 Sequence Detection System (PE Biosystems, Warrington, Cheshire, UK).

Cell counting

For each mouse pancreas, sections were analysed by digitally photographing 10 consecutive microscopic fields at ×400 total magnification. The number of myofibroblasts (α-SMA positive) or fibrocytes (CD45 and Col 1 double-positive) was quantified, and the proportion of BM-derived (Y chromosome positive) myofibroblasts and fibrocytes was expressed as a percentage.

Statistics

Results are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Mean values of the experimental groups were compared by Student’s unpaired t-tests. P-values of <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Development of pancreatic fibrosis

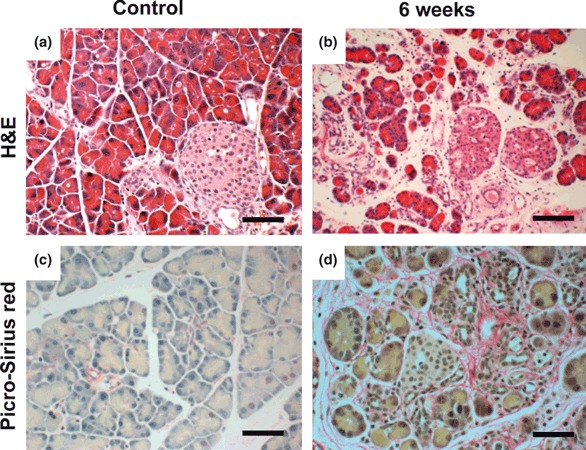

In the saline-treated mice, the histology of the pancreas was normal (Figure 2a,c). Tissue damage with atrophy of acinar cells, deformed architecture, pseudo-tubular complex formation, intralobular collagen deposition and severe fibrotic changes, which are the characteristic features of chronic pancreatitis were found after 6 weeks of high-dose cerulein treatment (Figure 2b,d). Irradiation, required for BM transplant, did not cause pancreatic fibrosis as far as we could determine by morphology and Picro-Sirius red staining.

Figure 2.

Histology of the pancreas from saline- (control group) or cerulein-treated female mice that received male bone marrow transplants. H&E staining and collagen staining in the pancreas from the control group showed normal pancreatic structure and collagen distribution (a and c, scale bars = 100 μm). Large-scale collagen deposition, inflammation, acinar cell atrophy and structural changes in the pancreas were demonstrated in the mice receiving cerulein over the 6-week period (b and d, scale bars = 100 μm).

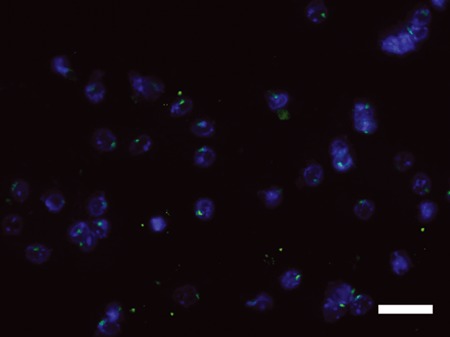

Circulating fibrocytes are derived from BM

To evaluate whether the circulating fibrocytes were derived from BM, the CD45+Col 1+ fibrocytes were isolated from PB by FACS, centrifuged onto slides and then probed by FISH for the Y chromosome. The Y chromosome could be detected in these cells, confirming that these fibrocytes were BM-derived (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

FISH for Y chromosome detection on fluorescence-activated cell sorting-isolated CD45+Col 1+ fibrocytes from peripheral blood showed that these cells are bone marrow-derived (Y chromosome, green; DAPI, blue). Scale bar = 50 μm.

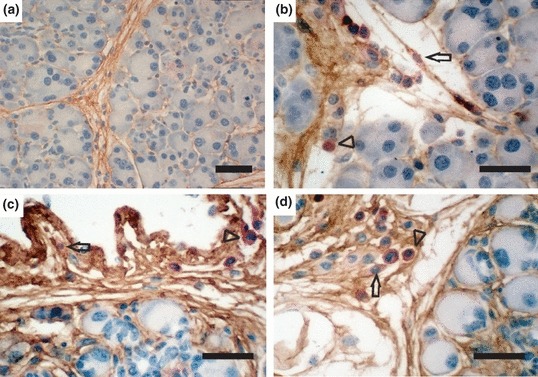

BM-derived fibrocytes in the pancreas

To determine the morphology of the CD45+Col 1+ fibrocytes in cerulein-induced acute pancreatitis and chronic fibrosis, we performed double immunohistochemical staining for CD45 and Col 1, two acknowledged markers of fibrocytes (Reilkoff et al. 2011). CD45+ cells were found only in collagen 1-stained areas (Figure 4b–d) in the pancreata of the mice that had either cerulein-induced acute pancreatitis or chronic pancreatic fibrosis, while these CD45+ cells were not detected in control mice (Figure 4a). Some of the CD45+ cells were round, typical of leucocytes. However, some of the CD45+ cells were spindle-shaped, typical of myofibroblasts, suggesting these CD45+ cells were fibrocytes and not macrophages (Reilkoff et al. 2011).

Figure 4.

IHC double staining for CD45 (red) and Col 1 (brown) of the pancreas from female mice that received bone marrow transplants from male wild-type donor mice followed by vehicle injections for 6 weeks (a, scale bar = 100 μm), or cerulein injections for 1 day (b, scale bar = 50 μm) or 6 weeks (c and d, scale bar = 50 μm). CD45+ cells were found only in the Col 1-stained areas after both acute and chronic pancreatitis. Arrows show spindle-shaped CD45+ cells (fibrocytes). Arrowheads show CD45+ cells with a round shape typical of leucocytes.

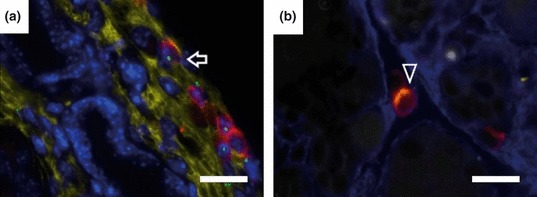

To ascertain whether any of the fibrocytes in the pancreas were BM-derived, double immunofluorescence staining for CD45 and Col 1 was combined with ISH for Y chromosome detection. BM-derived CD45+Col 1+ fibrocytes were detected in the pancreas from 6-week cerulein-injected mice (Figure 5a). We sought to quantify the frequency of fibrocytes in the CD45+ cell population, measuring the fraction of CD45-expressing cells that co-expressed Col 1 [10 high-power magnification fields (400×) per mouse], this being 17.5 ± 3.3% in the fibrosis group (n = 4).

Figure 5.

Immunofluorescence staining combined with FISH for Y chromosome detection in chronic pancreatitis. (a) Arrow shows a bone marrow-derived CD45+Col 1+ fibrocyte (Y chromosome, green; CD45, red; Col 1, yellow; DAPI, blue). (b) Arrowhead shows a CD45+α-SMA+ cell (CD45, red; α-SMA, yellow; Col 1, blue). Scale bars = 25 μm. SMA, smooth muscle actin.

To see whether CD45+ cells can further differentiate into myofibroblasts, double immunostaining for CD45 and α-SMA was performed. CD45/α-SMA double-positive cells were found in the pancreas at a low frequency (4.5 ± 3%) in the fibrosis group (Figure 5b).

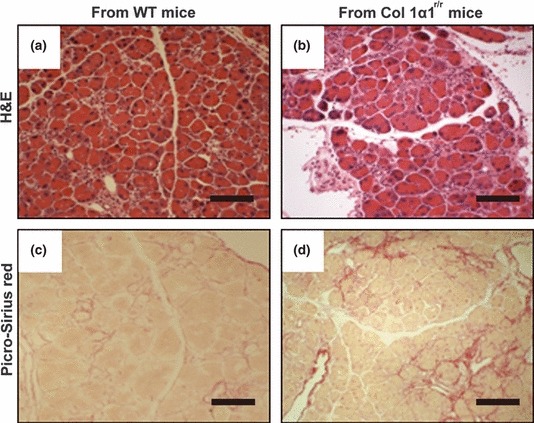

The functional role of BM-derived cells

Although our results demonstrate that BM-derived fibrocytes and myofibroblasts appear to be intimately associated with pancreatic fibrosis, it is unclear whether these BM-derived cells actually functionally contribute to the fibrosis in a meaningful way. To explore this possibility, the effect of Col 1α1r/r BM transplantation was assessed in a mild pancreatic fibrosis model. The results showed that the pancreata of mice that were recipients of Col 1α1r/r BM had extensive pericellular fibrosis, whereas the pancreata of mice that were recipients of WT BM had less collagen deposition (Figure 6). BM-derived myofibroblasts were detected by FISH for the Y chromosome in the pancreata of female mice receiving Col 1α1r/r male BM. The measurement of fibrotic areas, based on Picro-Sirius red staining, illustrated that recipients of Col 1α1r/r male BM had more fibrosis (P < 0.05, Table 1).

Figure 6.

Histology of the pancreas from female mice that received bone marrow (BM) transplants from male wild-type (a and c) or Col 1α1r/r mice (b and d) followed by low-dose cerulein injections for 10 weeks. H&E staining and Picro-Sirius red staining show that more severe fibrosis develops in the mice transplanted with BM from Col 1α1r/r mice. Scale bars = 250 μm.

Table 1.

Histological analysis of the pancreas from female mice that had received bone marrow (BM) from either wild-type (WT) or ColIα1r/r male mice

| (A) BM from WT (No injury) | (B) BM from WT (Cerulein 10 week) | (C) BM from ColIα1r/r (Cerulein 10 week) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sirius red staining (%) | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 2.94 ± 2.01* | 6.65 ± 3.62*† |

| Number of myofibroblasts (/50 acinar cells) | 2.14 ± 1.72 | 5.29 ± 2.64* | 8.11 ± 2.62*† |

| Percentage of BM-derived myofibroblasts | 0 | 8.64 ± 4.45* | 10.05 ± 5.21* |

Values are mean ± SEM (n = 4 mice per group). *P < 0.05 vs. (A); †P < 0.05 vs. (B).

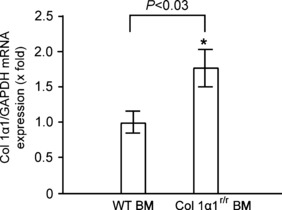

The quantitative RT-PCR analysis of mRNA expression of Col 1α1, a precursor of type 1 collagen, known to be a major component of the ECM in pancreatic fibrosis, was also in line with the histological observations. The levels of Col 1α1 mRNA expression were approximately 1.5-fold higher in the pancreata of the Col 1α1r/r BM recipients compared with those receiving WT BM (Figure 7). The number of myofibroblasts was also significantly increased in the pancreata of the Col 1α1r/r BM recipients compared with those receiving WT BM (Table 1).

Figure 7.

Real-time PCR analysis of mRNA expression in the pancreas. Total RNA was extracted from the pancreas of the mice that have received bone marrow (BM) with different genotypes followed by cerulein injections for 10 weeks. The mRNA expression of Col 1α1 was measured by quantitative PCR, and expression levels were normalized to the level of GAPDH. Values are mean ± SEM (n = 4). *P < 0.05. This result reveals that the level of mRNA for Col 1α1 is relatively higher in the mice transplanted with Col 1α1r/r BM.

Discussion

There is a strong association between fibrocytes with diverse forms of chronic inflammation (Reilkoff et al. 2011). Thought to be derived from a subpopulation of CD14-positive monocytes, they can be identified by the production of collagen along with the expression of CD34 and/or CD45; additionally, in tissues, their spindle shape distinguishes them from macrophages (Reilkoff et al. 2011).

Fibrocytes can traffic into the inflamed and fibrotic pancreas

The origin of fibrocytes in tissues is still unclear. Three studies (Frid et al. 2006; Haudek et al. 2006; Varcoe et al. 2006) have suggested that tissue fibrocytes differentiate from circulating precursors within tissue sites and not in the PB; however, tracking experiments in mice (Abe et al. 2001; Schmidt et al. 2003) have suggested that injected fibrocytes, not precursor cells, can rapidly migrate into inflamed sites, suggesting that tissue fibrocytes can come from either precursor cells or circulating collagen-producing fibrocytes. In our study, we demonstrated that CD45+Col 1+ fibrocytes are derived from BM and do exist in the PB. This trafficking is undoubtedly aided by the expression of a variety of adhesion and motility factors along with chemokine receptors on fibrocytes, leading to their accumulation in chronically inflamed tissue such as reported here for the inflamed pancreas (Reilkoff et al. 2011).

Fibrocytes can be found in the fibrotic pancreas and can differentiate into myofibroblasts

Barth et al. (2002) first reported that the CD34+ fibrocyte-like cells could be found in the human inflamed and neoplastic pancreas. Interestingly, these CD34+ cells were also detected in normal pancreas, encircling acinar, ductal and vascular structures, and characterized by long dendritic-like projections. The increased number of CD34+ fibrocyte-like cells paralleled an increase in the number of α-SMA myofibroblasts in chronic pancreatitis. In contrast, while we found CD45+Col 1+ fibrocytes in pancreatic fibrosis, none were found in the normal pancreas of control mice. The Y chromosome was also detected in these CD45+Col 1+ fibrocytes indicating that these cells were BM derived and none of these BM-derived cells were found in the normal pancreas. Furthermore, we demonstrated that a few of these CD45+ fibrocytes can co-express α-SMA indicating a minor contribution to the myofibroblast population during pancreatic fibrosis. However, this contribution may be an underestimate as CD45 is most likely down-regulated during the differentiation of fibrocytes into α-SMA+ myofibroblasts (Schmidt et al. 2003).

BM-derived cells functionally contribute to pancreatic fibrosis

Although a contribution of BM to fibrocytes and myofibroblasts has been shown in various organs including pancreas, analysis of the individual functional role of BM-derived cells, separate from resident PaSCs, has not been fully investigated. A functional contribution of BM-derived cells to fibrosis can be inferred by the observation that genetically modified BM cells can alter the severity of chronic inflammation in the intestine, fibrosis in the liver and neovascularization in tumours (Bamba et al. 2006; Russo et al. 2006; Nolan et al. 2007). Our data show that mice receiving BM from Col 1α1r/r mice developed more extensive fibrosis, at both the protein and mRNA level, suggesting that BM-derived cells do function as fibrogenic cells in pancreatic fibrosis. The excessive collagen deposition in the recipients of Col 1α1r/r BM is most likely because these Col 1α1r/r BM cells secrete mutant Col 1, resistant to collagen degradation by collagenases. The percentage of BM-derived myofibroblasts was also increased in the recipients of Col 1α1r/r BM, but the reason for this is not clear.

It has been proposed that BM-derived cells in non-haematopoietic tissues play more crucial or different roles compared with resident cells. For example, Nolan et al. (2007) demonstrated that specific ablation of BM-derived endothelial cells remarkably reduced tumour growth despite the fact that the contribution of these cells was only 10–30%, suggesting a critical role of these cells in tumour neovascularization. In the kidney, it has also been shown that BM-derived renal myofibroblasts have the ability to produce pro-collagen 1 and contribute to ECM deposition (Broekema et al. 2007). Furthermore, by inducing liver fibrosis in Col 1α1r/r mice, Issa et al. (2003) demonstrated that the myofibroblasts in Col 1α1r/r mice were not only producing Col 1 that was resistant to collagenase degradation, but the cells were also more resistant to apoptosis. Decreased hepatocyte regeneration was also seen in that study, which was considered to result from the accumulation of undegraded Col 1. In our study, the higher level of Col 1α1 mRNA in mice that were recipients of Col 1α1r/r BM may suggest the Col 1α1r/r BM-derived myofibroblasts produce more Col 1a1 (resistant to collagenase degradation) than myofibroblasts derived from WT BM. The results are in line with this suggestion, as collagen deposition was increased in recipients of Col 1α1r/r BM cells.

Conclusion

We have demonstrated that collagen-producing CD45+Col 1+ fibrocytes are derived from BM. These fibrocytes can populate the fibrotic pancreas, being located in the collagen-rich areas and seemingly contribute to pancreatic fibrosis by differentiation into myofibroblasts that produce collagen.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by a grant from Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Taiwan (CMRPG370721 and CMRPG370722) and Cancer Research UK.

Conflict of interest

No conflicts of interest were declared.

References

- Abe R, Donnelly SC, Peng T, Bucala R, Metz CN. Peripheral blood fibrocytes: differentiation pathway and migration to wound sites. J. Immunol. 2001;166:7556–7562. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.12.7556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen DK. Mechanisms and emerging treatments of the metabolic complications of chronic pancreatitis. Pancreas. 2007;35:1–15. doi: 10.1097/mpa.0b013e31805d01b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamba S, Lee CY, Brittan M, et al. Bone marrow transplantation ameliorates pathology in interleukin-10 knockout colitic mice. J. Pathol. 2006;209:265–273. doi: 10.1002/path.1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth PJ, Ebrahimsade S, Hellinger A, Moll R, Ramaswamy A. CD34+ fibrocytes in neoplastic and inflammatory pancreatic lesions. Virchows Arch. 2002;440:128–133. doi: 10.1007/s00428-001-0551-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrman SW, Fowler ES. Pathophysiology of chronic pancreatitis. Surg. Clin. North Am. 2007;87:1309–1324. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellini A, Mattoli S. The role of the fibrocyte, a bone marrow-derived mesenchymal progenitor, in reactive and reparative fibroses. Lab. Invest. 2007;87:858–870. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broekema M, Harmsen MC, van Luyn MJ, et al. Bone marrow-derived myofibroblasts contribute to the renal interstitial myofibroblast population and produce procollagen I after ischemia/reperfusion in rats. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2007;18:165–175. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005070730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesney J, Metz C, Stavitsky AB, Bacher M, Bucala R. Regulated production of type I collagen and inflammatory cytokines by peripheral blood fibrocytes. J. Immunol. 1998;160:419–425. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Direkze NC, Forbes SJ, Brittan M, et al. Multiple organ engraftment by bone-marrow-derived myofibroblasts and fibroblasts in bone-marrow-transplanted mice. Stem Cells. 2003;21:514–520. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.21-5-514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frid MG, Brunetti JA, Burke DL, et al. Hypoxia-induced pulmonary vascular remodeling requires recruitment of circulating mesenchymal precursors of a monocyte/macrophage lineage. Am. J. Pathol. 2006;168:659–669. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartlapp I, Abe R, Saeed RW, et al. Fibrocytes induce an angiogenic phenotype in cultured endothelial cells and promote angiogenesis in vivo. FASEB J. 2001;15:2215–2224. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0049com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haudek SB, Xia Y, Huebener P, et al. Bone marrow-derived fibroblast precursors mediate ischemic cardiomyopathy in mice. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:18284–18289. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608799103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Issa R, Zhou X, Trim N, et al. Mutation in collagen-1 that confers resistance to the action of collagenase results in failure of recovery from CCl4-induced liver fibrosis, persistence of activated hepatic stellate cells, and diminished hepatocyte regeneration. FASEB J. 2003;17:47–49. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-0494fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda N, Toi M, Nakayama H, et al. The distribution and role of myofibroblasts and CD34-positive stromal cells in normal pancreas and various pancreatic lesions. Histol. Histopathol. 2004;19:59–67. doi: 10.14670/HH-19.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin WR, Brittan M, Alison MR. The role of bone marrow-derived cells in fibrosis. Cells Tissues Organs. 2008;188:178–188. doi: 10.1159/000113530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Wu H, Byrne M, Jeffrey J, Krane S, Jaenisch R. A targeted mutation at the known collagenase cleavage site in mouse type I collagen impairs tissue remodeling. J. Cell Biol. 1995;130:227–237. doi: 10.1083/jcb.130.1.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowenfels AB, Maisonneuve P, Cavallini G, et al. Pancreatitis and the risk of pancreatic cancer. International Pancreatitis Study Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 1993;328:1433–1437. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199305203282001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malka D, Hammel P, Maire F, et al. Risk of pancreatic adenocarcinoma in chronic pancreatitis. Gut. 2002;51:849–852. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.6.849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrache F, Pendyala S, Bhagat G, Betz KS, Song Z, Wang TC. Role of bone marrow-derived cells in experimental chronic pancreatitis. Gut. 2008;57:1113–1120. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.143271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori L, Bellini A, Stacey MA, Schmidt M, Mattoli S. Fibrocytes contribute to the myofibroblast population in wounded skin and originate from the bone marrow. Exp. Cell Res. 2005;304:81–90. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan DJ, Ciarrocchi A, Mellick AS, et al. Bone marrow-derived endothelial progenitor cells are a major determinant of nascent tumor neovascularization. Genes Dev. 2007;21:1546–1558. doi: 10.1101/gad.436307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Omary MB, Lugea A, Lowe AW, Pandol SJ. The pancreatic stellate cell: a star on the rise in pancreatic diseases. J. Clin. Invest. 2007;117:50–59. doi: 10.1172/JCI30082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilling D, Buckley CD, Salmon M, Gomer RH. Inhibition of fibrocyte differentiation by serum amyloid P. J. Immunol. 2003;171:5537–5546. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.5537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilling D, Tucker NM, Gomer RH. Aggregated IgG inhibits the differentiation of human fibrocytes. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2006;79:1242–1251. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0805456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangan GK, Tesch GH. Quantification of renal pathology by image analysis. Nephrology. 2007;12:553–558. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1797.2007.00855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilkoff RA, Bucala R, Herzog EL. Fibrocytes: emerging effector cells chronic inflammation. Nat. Immunol. 2011;11:427–435. doi: 10.1038/nri2990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo FP, Alison MR, Bigger BW, et al. The bone marrow functionally contributes to liver fibrosis. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1807–1821. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt M, Sun G, Stacey MA, Mori L, Mattoli S. Identification of circulating fibrocytes as precursors of bronchial myofibroblasts in asthma. J. Immunol. 2003;171:380–389. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.1.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varcoe RL, Mikhail M, Guiffre AK, et al. The role of the fibrocyte in intimal hyperplasia. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2006;4:1125–1133. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01924.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe T, Masamune A, Kikuta K, et al. Bone marrow contributes to the population of pancreatic stellate cells in mice. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 2009;297:G1138–G1146. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00123.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witt H, Apte MV, Keim V, Wilson JS. Chronic pancreatitis: challenges and advances in pathogenesis, genetics, diagnosis, and therapy. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1557–1573. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H, Byrne MH, Stacey A, et al. Generation of collagenase-resistant collagen by site-directed mutagenesis of murine pro alpha 1(I) collagen gene. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1990;87:5888–5892. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.15.5888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]