Abstract

Chronic hyperglycemia exerts a deleterious effect on endothelium, contributing to endothelial dysfunction and microvascular complications in poorly controlled diabetes. To understand the underlying mechanism, we studied the effect of endothelin-1 (ET-1) on endothelial production of Forkhead box O1 (FOXO1), a forkhead transcription factor that plays an important role in cell survival. ET-1 is a 21-amino acid peptide that is secreted primarily from endothelium. Using adenovirus-mediated gene transfer approach, we delivered FOXO1 cDNA into cultured human aorta endothelial cells. FOXO1 was shown to stimulate B cell leukemia/lymphoma 2-associated death promoter (BAD) production and promote cellular apoptosis. This effect was counteracted by ET-1. In response to ET-1, FOXO1 was phosphorylated and translocated from the nucleus to cytoplasm, resulting in inhibition of BAD production and mitigation of FOXO1-mediated apoptosis. Hyperglycemia stimulated FOXO1 O-glycosylation and promoted its nuclear localization in human aorta endothelial cells. This effect accounted for unbridled FOXO1 activity in the nucleus, contributing to augmented BAD production and endothelial apoptosis under hyperglycemic conditions. FOXO1 expression became deregulated in the aorta of both streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice and diabetic db/db mice. This hyperglycemia-elicited FOXO1 deregulation and its ensuing effect on endothelial cell survival was corrected by ET-1. Likewise, FoxO1 deregulation in the aorta of diabetic mice was reversible after the reduction of hyperglycemia by insulin therapy. These data reveal a mechanism by which FOXO1 mediated the autocrine effect of ET-1 on endothelial cell survival. FOXO1 deregulation, resulting from an impaired ability of ET-1 to control FOXO1 activity in endothelium, may contribute to hyperglycemia-induced endothelial lesion in diabetes.

Endothelin-1 (ET-1) is a 21-amino acid peptide that is produced primarily by vascular endothelial cells. ET-1 acts to regulate vascular tone via its two cognate receptors, ETA, which is expressed in smooth muscle cells, and ETB, which is present on endothelial cells (1). Binding of ET-1 to the ETA receptor causes sodium retention in smooth muscle cells, the effect of which accounts for vasoconstriction. In contrast, binding of ET-1 to the ETB receptor stimulates nitric oxide (NO) production in endothelial cells, the effect of which contributes to vasodilation. These two opposing effects of ET-1 act in concert to regulate blood pressure, contributing to the fine-tuning of microvascular circulation (1, 2). Deregulation in endothelial ET-1 production is associated with the pathophysiology of a variety of vascular diseases including hypertension, atherosclerosis, diabetes, and ischemic heart disease (3–9).

Apart from its action on vascular tone, ET-1 exerts a cytoprotective effect on cell survival. This antiapoptotic action of ET-1 is observed in a number of cell types including cardiac myocytes (10), human umbilical vein endothelial cells (11), renal carcinoma cells (12), ovarian carcinoma cells (13), and prostate epithelial cells (14). A prevailing notion is that ET-1 signaling through AKT/protein kinase B (PKB) contributes to the prosurvival effect of ET-1 on cells. Consistent with this notion is the observation that ET-1 binding to its cognate receptors results in the activation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)-AKT/PKB signaling cascade in a variety of cell types (10, 13, 15). Nevertheless, the underlying mechanism and physiology by which ET-1 mediates its antiapoptotic effect on endothelial cells remains elusive.

To characterize the ET-1 signaling pathway in endothelial cell survival, we studied the effect of ET-1 on Forkhead box O (FOXO)-1 production in human aorta endothelial cells (HAEC). FOXO1 belongs to a subfamily of transcription factors that is characterized by a highly conserved winged-helix DNA binding motif, termed forkhead domain, which includes FOXO1, FOXO3, FOXO4, and FOXO6 (16, 17). These forkhead proteins are substrates of Akt/PKB and serum- and glucocorticoid-induced kinase, playing important roles in mediating insulin or IGF-I action on the expression of genes involved in cell growth, metabolism, and differentiation (16–18). Its orthologs abnormal Dauer formation 16 in Caenorhabditis elegans and dFoxO in Drosophilia contribute to the regulation of oxidative stress and longevity (19–21). Insulin (or IGF-I) exerts some of its inhibitory effect on target gene expression via a conserved insulin-responsive element (5′-TG/ATTTT/G-3′) in the promoter (16, 17, 22). In the absence of insulin (or IGF-I), FOXO1 proteins reside in the nucleus and bind as a trans-activator to insulin-responsive element, enhancing promoter activity. In response to insulin (or IGF-I) stimulation, FOXO1 proteins are phosphorylated by AKT/PKB through the PI3K-dependent pathway, resulting in FOXO1 nuclear export and inhibition of target gene expression (23–29). This phosphorylation-dependent subcellular redistribution serves as an acute mechanism for insulin (or IGF-I) to regulate FOXO1 transcriptional activity in cells (16–18, 22, 30). Based on the observation that ET-1 promotes AKT/PKB activation, we hypothesized that FOXO1 mediates the autocrine effect of ET-1 on endothelial cell survival. We tested this hypothesis and addressed the underlying physiological significance in vitro using HAEC and in vivo using both streptozotocin (STZ)-induced insulin-deficient and insulin-resistant db/db models.

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and adenovirus transduction

HAEC were obtained from Cambrex (Lonza Cambrex Bioscience Walkersville Inc., Walkersville, MD) and cultured in endothelial basal medium-2 (EBM-2) supplemented with endothelial growth media SingleQuots (Cambrex) in the absence or presence of 100 nm ET-1, as described (31, 32). HAEC were transduced with adenoviral vectors at a defined dose of 100 plaque-forming units (pfu) per cell. The adenoviral vectors used were as follows: Adv-CMV-FOXO1 expressing wild type FOXO1 (1.0 × 1011 pfu/ml) and the null adenovirus Adv-null (1.25 × 1011 pfu/ml), as described (33). Adenoviral vectors were produced in human embryonic kidney 293 cells and purified as described (34).

Animal studies

Institute for Cancer Research (ICR) mice (female, 8 wk old) were purchased from Taconic (Germantown, NY). Male db/db mice and heterozygous db/+ littermates (6 wk old) were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Mice were fed standard rodent chow and water ad libitum in sterile cages with a 12 h-light, 12-h dark cycle. To induce diabetes, mice were ip injected with STZ at the dose of 240 mg/kg (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). A group of age- and sex-matched ICR mice without STZ treatment was used as normal control. Blood glucose levels were measured using Glucometer Elite (Bayer, Indianapolis, IN). One week after STZ administration, diabetic mice were stratified by blood glucose levels and randomly assigned to two groups. One group received insulin therapy and the other group was mock treated with PBS as diabetic control. Insulin therapy was established by implanting the LinBit insulin implant (LinShin Canada Inc., Toronto, Canada) for providing sustained basal insulin release. Diabetic mice were anesthetized with 100 mg/kg ketamine and 10 mg/kg xylazine as described (35), followed by inserting one LinBit insulin pellet sc under the middorsal skin, according to the manufacturer's instruction. In addition, each diabetic mouse in the insulin therapy group received a once-daily sc insulin injection (0.25–0.5 IU, Humulin N; Eli Lilly & Co., Indianapolis, IN) in the morning for improving postprandial blood glucose control. When hyperglycemia was corrected after 1 wk of insulin treatment, the entire aorta (ascending aorta, aortic arch, and descending aorta) was surgically removed from individual mice. The ascending aorta was used for immunohistochemistry, using anti-FOXO1 antibody as described (34). The remaining portion of the aorta (aortic arch and descending aorta) was used for isolation of total RNA for real-time quantitative RT-PCR. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine.

RNA isolation and real-time quantitative RT-PCR

Individual aorta were homogenized in 200 μl Trizol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Total RNA was prepared following the manufacturer's instruction and subjected to real-time quantitative RT-PCR using specific primers against FOXO1 or β-actin mRNA, as described (36).

Immunofluorescent microscopy

HAEC (5 × 104 cell/well) were seeded onto six-well dishes (Corning Inc., Corning, NY) containing sterile human fibronectin 22-mm-round glass coverslips (BD Bioscience, Bedford, MA) and grown as previously described (31). After 24 h incubation, HAEC were serum starved for 6 h, followed by the addition of 100 nm insulin (Invitrogen) or 100 nm ET-1 (Sigma Aldrich) into culture medium. Control wells of cells were mock treated with serum-free EBM-2 medium. As additional control, HAEC were cultured with both ET-1 (100 nm) and ET-1 receptor inhibitor IRL1038 (50 μm; Sigma-Aldrich). After 30 min incubation, cells were washed with PBS and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (USB Corp., Cleveland, OH), followed by anti-FoxO1 immunocytochemistry, as described (36).

FOXO1 O-glycosylation assay

This assay relies on the property of wheat-germ agglutinin (WGA) in binding with high-affinity with O-glycosylated proteins (37). To study FOXO1 O-glycosylation, HAEC were cultured in the presence of 5.6 or 25 mm glucose for 24 h. Cell protein lysates (250 μg protein) were incubated with 30 μl of succinylated WGA-agarose beads (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) for 2 h at 4 C. WGA-agarose bead-bound proteins were washed with PBS buffer and subjected to immunoblot analysis using anti-FOXO1 antibody.

Immunoblot assay

HAEC (∼2 × 106 cells) were lysed in 400 μl of M-PER supplemented with 4-μl Halt protease inhibitor cocktail (Pierce, Rockford, IL), followed by centrifugation at 13,000 rpm for 10 min. Subsequent preparation of nuclear and cytosolic fractions for immunoblot analysis was described (33). Aliquots of protein extracts (20 μg) were resolved on 4–20% SDS-PAGE. Proteins were blotted onto polyvinyl difluoride membranes, which were subjected to immunoblot assay using the following antibodies: rabbit anti-FOXO1 antibody (1:3000 dilution, developed in our own laboratory) (38); rabbit antiphosphorylated FOXO1 (Ser256, 1:3000 dilution; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA); rabbit anti-B cell leukemia/lymphoma 2 (BCL-2; 1:2000 dilution, sc-783; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA); rabbit anti-BCL-2-associated X protein (BAX; 1:1000 dilution, sc-6236; Santa Cruz Biotechnology); rabbit anti-BCL-2 homologous killer (BAK; 1:2000 dilution, catalog no. 04-443; Millipore Upstate, Billerica, MA); and rabbit anti-B cell leukemia/lymphoma 2-associated death promoter (BAD) antibody (1:2000 dilution, catalog no. 04-432; Millipore Upstate). Mouse monoclonal anti-TATA box binding protein (TBP) antibody (1:5000 dilution, catalog no. ab818; Abcam, Cambridge, MA) was used for detecting control nuclear TBP protein in the immunoblots. The protein bands were visualized by chemiluminescent Western detection reagents (Pierce, Rockford, IL). The intensity of the protein bands was quantified by densitometry using the NIH Image software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

Caspase-3 assay

HAEC (∼2× 105 cells) were seeded in six-well dishes. After 24 h incubation, cells were transduced with Adv-null or Adv-FOXO1 vector (100 pfu/cell). After 24 h incubation in presence or absence of 100 nm ET-1, cells were collected for the determination of caspase-3 activity using a caspase-3 activity assay kit (catalog no. QIA70; Calbiochem, Gibbstone, NJ).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

A ChIP was performed to study the interaction between FOXO1 and BAD promoter in HAEC as described (34). HAEC (2 × 105 cells) were cultured in EBM-2 medium supplemented with 5.6 or 25 mm glucose in the absence or presence of 100 nm ET-1. After 24 h incubation, cells were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde, followed by sonication in a Microson 100-W Ultrasonicator (Structure Probe, West Chester, PA) at 30% of maximum power for five consecutive cycles of 20-sec pulses. After centrifugation at 18,000 × g for 10 min, the supernatant was incubated with 5 μg polyclonal rabbit anti-FoxO1 antibody that was generated in our laboratory (38), followed by immunoprecipitation using the ChIP assay kit (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY). The immunoprecipitates were analyzed by PCR assay to detect coimmunoprecipitated DNA using the BAD promoter-specific primers (forward, 5′-GACCTGGGTCTTCAGAAATAG-3′, reverse, 5′-CACAGAAGAAGTGAGGAAGTC-3′) flanking the DNA region (−1465/−864 nt) of the human BAD promoter. As an off-target control, a pair of primers (forward, 5′-CTTCCTCGCC CGAAGAGCGC-3′ and reverse, 5′-GGGCTCGGGTCCCGGTGACG-3′) flanking the human BAD coding region (+721/+1160 nt) was used.

BAD promoter activity assay

The mouse BAD promoter was amplified from C57BL/6J mouse genomic DNA by PCR using primers (5′-AGTGGTCTTTCCTACCCAGG-3′ for forward reaction and 5′-TCCCATTTGGATCCTGGAGG-3′ for reverse reaction). The DNA fragment flanking the mouse BAD promoter (−1246/+1 nt) was cloned into the pGL3-basic vector encoding the Firefly luciferase gene (Promega, Madison, WI). The resulting plasmid pBAD-Luc was cotransfected with pGL4.75 encoding the Renilla luciferase gene (Promega) into HAEC, followed by transduction with the Adv-FOXO1 or the control Adv-null vector (100 pfu/cell). After 24 h incubation in serum-free medium in the presence or absence of ET-1 (100 nm), cells were subjected to dual-luciferase activity assay for determining BAD promoter activity.

Statistical analysis

Data were presented as mean ± sem. Statistical analysis was performed using a two-tailed unpaired Student's t test. Pair-wise comparisons were performed to study the significance between different conditions. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

FoxO1 expression is up-regulated in aorta endothelium of diabetic mice

To determine the impact of hyperglycemia on endothelial FoxO1 expression in vivo, we studied the expression of FoxO1 in the aorta of diabetic mice. ICR female mice (body weight 26.7 ±1.8 g at 8 wk of age) were injected ip with STZ (240 mg/kg, n = 8). Two days after STZ administration, all STZ-treated mice developed severe diabetes (blood glucose levels 518 ± 32 mg/dl), in comparison with sex- and age-matched controls (blood glucose levels 123 ± 14 mg/dl, n = 6). Mice were killed 2 wk after STZ injection, and the aorta of individual mice were subjected to anti-FoxO1 antibody immunohistochemistry. As shown in Fig. 1, intensive FoxO1 immunostaining was detected in the aortic endothelium in STZ-induced diabetic mice but not in normal control mice. As a control, we applied preimmune rabbit serum to immunohistochemistry. The aortic endothelium of both normal and STZ-induced diabetic mice was stained negative (data not shown). To corroborate this finding, we isolated total RNA from the aorta of STZ-induced diabetic vs. control mice, followed by real-time quantitative RT-PCR assay. An 8-fold induction in FoxO1 mRNA expression was detected in the aorta of STZ-induced diabetic mice (Fig. 1G). In contrast, aortic FoxO3 and FoxO4 mRNA levels remained unchanged in STZ-induced diabetic vs. control groups. Furthermore, we subjected the aorta of individual mice to anti-FoxO1 immunoblot assay, demonstrating that aortic FoxO1 protein levels were significantly up-regulated in STZ-induced diabetic mice (Fig. 1H). These data indicate that FoxO1 expression in the aorta becomes deregulated in response to prevailing hyperglycemia in diabetic mice.

Fig. 1.

Endothelial FoxO1 expression in the aorta of diabetic mice. ICR mice (female, 8 wk old) were rendered diabetic by administration of a single dose of STZ (240 mg/kg). STZ-induced diabetic (n = 8) and control (n = 6) mice were killed 2 wk after STZ administration. Aorta were isolated from normal (A–C) and diabetic (D–F) groups for anti-FoxO1 immunohistochemistry, followed by immunofluorescent microscopy. The elastic fibers of the aorta were autofluorescent green (A and D). FoxO1 was immunostained red in the endothelium (B and E). Merged images were shown in C and F. In addition, aliquots of aortic RNA were subjected to real-time quantitative RT-PCR for the determination of endothelial FoxO1, FoxO3, and FoxO4 mRNA levels using β-actin mRNA as control (G). The ascending aorta was homogenized for the preparation of total protein lysates, which were subjected to anti-FoxO1 immunoblot assay for determining aortic FoxO1 protein levels (H). Likewise, ascending aortas of db/db (n = 3, male, 10 wk old) and age- and sex-matched control (n = 3) were subjected to an anti-FoxO1 immunoblot assay (I). In addition, ICR mice (female, 8 wk old) were rendered diabetic by STZ these mice were randomly assigned to two groups (n = 6) receiving insulin therapy or PBS buffer. A group of nondiabetic mice (n = 6) was used as a normal control. After 1 wk of insulin therapy, the mice were killed under ad libitum condition for determining aortic FoxO1 protein levels (J). Bar, 50 μm. *, P < 0.05 vs. control by ANOVA.

To underpin the above conclusion, we determined aortic FoxO1 production in db/db mice, a commonly used genetic model of obesity and type 2 diabetes. When compared with age- and sex-matched lean control mice (n = 6), male db/db mice (n = 6) exhibited morbid obesity (body weight 43.1 ± 3.4 vs. 23.8 ± 1.8 g in the control group) and hyperglycemia (blood glucose levels 272 ± 41 vs. 128 ± 18 mg/dl, P < 0.001) at 10 wk of age under ad libitum conditions. Furthermore, db/db mice, as opposed to control mice, were associated with significantly increased FoxO1 production in the aorta (Fig. 1I).

We hypothesized that FoxO1 deregulation in the aorta is secondary to hyperglycemia in diabetic mice. To address this hypothesis, we rendered ICR mice diabetic after an ip dose of STZ as above. Diabetic mice were stratified by the degree of hyperglycemia (blood glucose 500 ± 26 mg/dl) and randomly assigned to two groups (n = 6/group), which received insulin therapy or PBS injection. One group of nondiabetic mice (n = 6) was included as normal control (blood glucose 137 ± 8 mg/dl). Insulin therapy was instituted by implanting the LinBit insulin implant under the middorsal skin of individual diabetic mice for providing basal insulin release, followed by once-daily sc insulin injection (0.25–0.5 IU per mouse) in the morning for controlling postprandial blood glucose levels. After 1 wk of insulin therapy for reducing hyperglycemia to the normal range (127 ± 58 mg/dl), the mice were killed for the isolating aortas, which were subjected to anti-FoxO1 immunoblot assay. FoxO1 protein levels were significantly up-regulated in the aorta of the STZ-induced diabetic mice (Fig. 1J). This effect was ameliorated but not to basal levels by insulin therapy, presumably due to inadequate blood glucose control in diabetic mice.

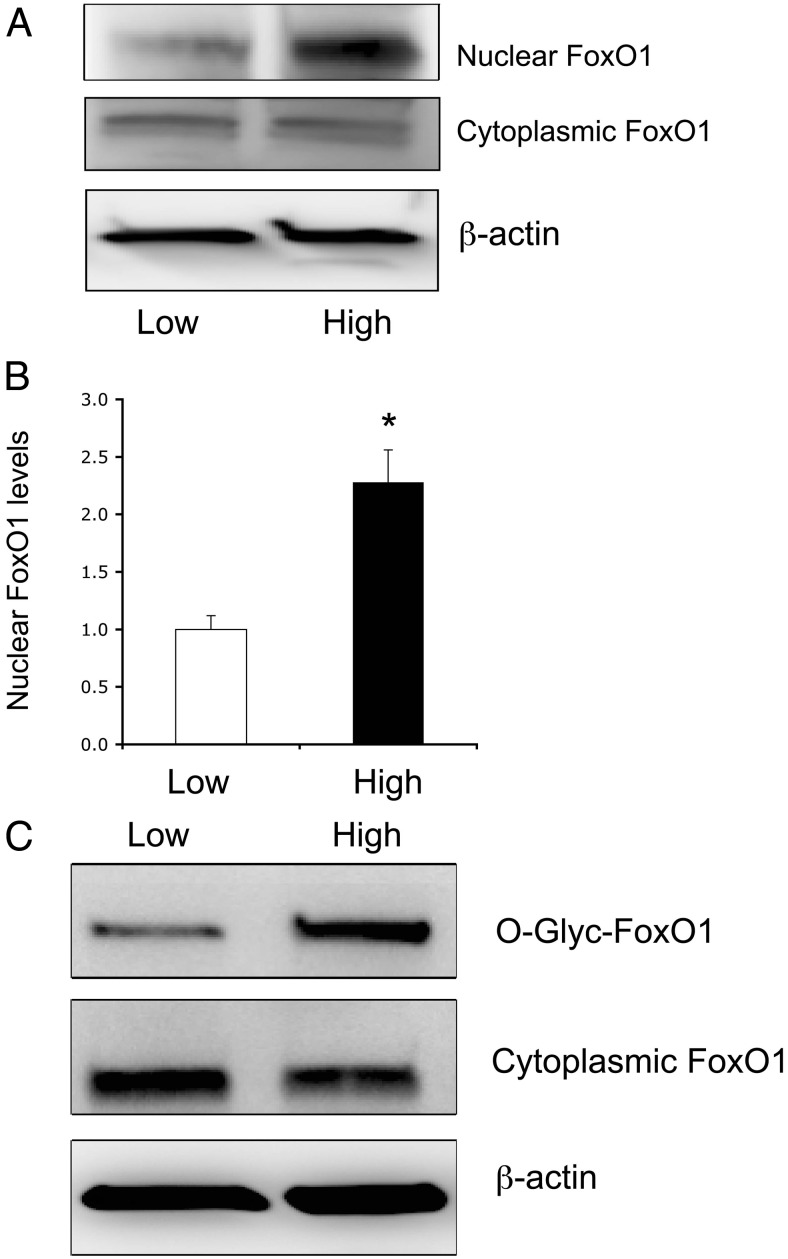

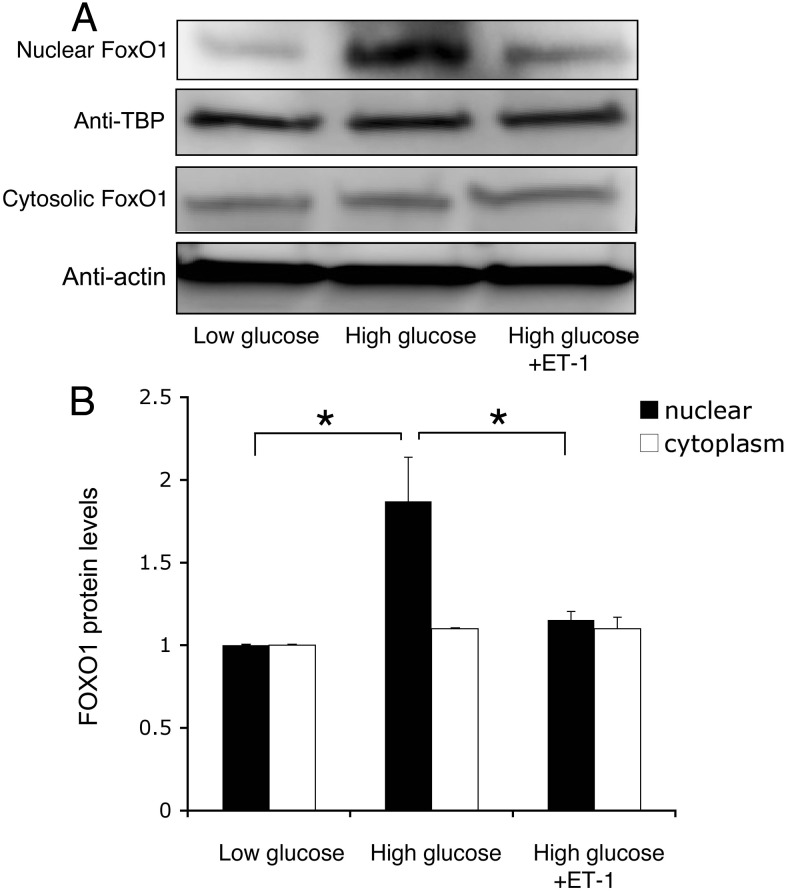

Hyperglycemia promotes FOXO1 O-glycosylation and nuclear localization

To recapitulate the above finding, we determined FOXO1 production in cultured HAEC under normal vs. hyperglycemic conditions. HAEC were cultured in EBM-2 containing 5.6 mm glucose (low glucose) or 25 mm glucose (high glucose). After 24 h incubation, cells were subjected to immunoblot analysis for the determination of FOXO1 protein levels in the nucleus vs. cytoplasm (Fig. 2A). FOXO1 was significantly up-regulated along with its predominant localization in the nucleus of HAEC under high-glucose conditions (Fig. 2B). In contrast, cytosolic FOXO1 protein levels remained unchanged, regardless of glucose concentrations in culture medium.

Fig. 2.

FOXO1 undergoes O-linked glycosylation under hyperglycemia conditions. HAEC were cultured in EBM-2 under low- (5.6 mm) or high (25 mm)-glucose conditions. After 24 h incubation, cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions of cells were prepared and subjected to immunoblot for the determination of FOXO1 subcellular distribution (A). The induction of FOXO1 nuclear protein levels in response to high glucose was determined (B). In addition, aliquots of cells were subjected to WGA affinity chromatography for the isolation and detection of O-glycosylated proteins by anti-FOXO1 immunoblot assay (C). Data were from three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05 vs. control.

To probe the underlying mechanism, we hypothesized that FOXO1 may be O-glycosylated in response to hyperglycemia. This hypothesis derived from previous observations that O-glycosylation of FOXO1 promotes its nuclear localization and enhances its transcriptional activity (37, 39, 40). To address this hypothesis, we studied the ability of FOXO1 to undergo O-linked glycosylation in HAEC that were cultured in the presence of 5.6 or 25 mm glucose, using WGA affinity chromatography as described (37). WGA binds with high affinity to O-glycosylated proteins, allowing their fractionation from native polypeptides. This assay detected a marked elevation in FOXO1 O-glycosylation in HAEC exposed to hyperglycemia (Fig. 2C).

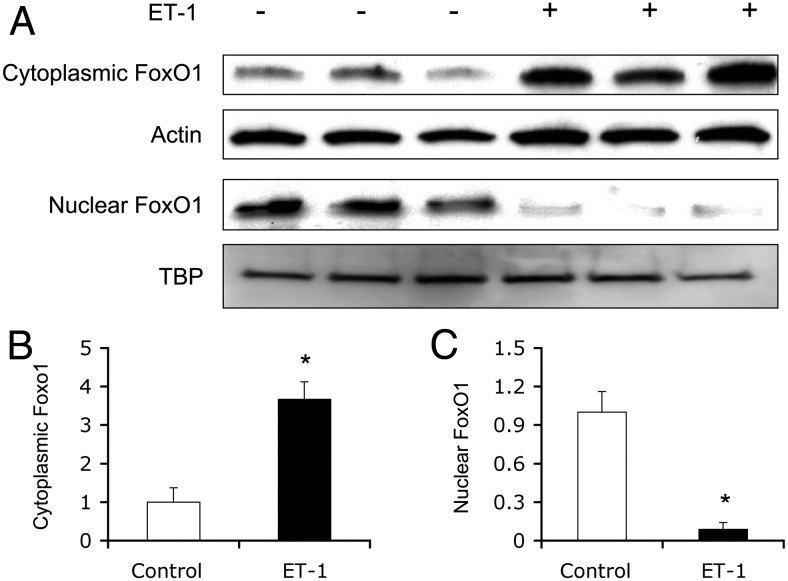

Effect of ET-1 on FOXO1 subcellular distribution in HAEC

To determine the effect of ET-1 on FOXO1 subcellular distribution, we treated HAEC with ET-1 for 30 min, followed by the separation of nuclear and cytosolic fractions. Aliquots of protein extracts (20 μg) were subjected to immunoblot analysis. In response to ET-1, FOXO1 was translocated from the nucleus to cytoplasm (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

ET-1 promotes FOXO1 nuclear exclusion in HAEC. HAECs (∼1 × 106 cells) were transduced with an Adv-FOXO1 vector (100 pfu/cell) in EBM-2 supplemented with 5.6 mm glucose. After 24 h incubation, cells were serum starved for 6 h and then were mock treated or treated with 100 nm ET-1 for 30 min. Cells were collected for the preparation of cytosolic and nuclear fractions, followed by immunoblot analysis using anti-FOXO1 antibody (A). The relative amount of FOXO1 in the cytoplasm was determined using actin as a control (B). Likewise, the relative amount of FoxO1 protein in the nucleus was quantified using nuclear TBP protein as a control (C). Data were from three independent experiments. *, P < 0.001 vs. control.

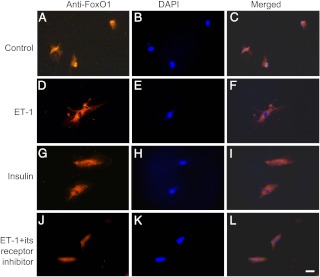

To ascertain these findings, we incubated HAEC in the absence or presence of ET-1 (100 nm) for 30 min, followed by anti-FoxO1 immunocytochemistry. FOXO1 was predominantly nuclear in the absence of ET-1 (Fig. 4, A–C). In response to ET-1, FOXO1 detected mainly in the cytoplasm (Fig. 4, D–F). As a control, we treated HAEC with insulin (100 nm) for 30 min, followed by immunocytochemistry. FOXO1 was preferentially localized in the cytoplasm (Fig. 4, G–I), correlating with the ability of FOXO1 to undergo insulin-dependent phosphorylation and nuclear exclusion (16, 17). As an additional control, we incubated HAEC in both ET-1 and its receptor inhibitor IRL1038, an agent that binds selectively to ET-1 receptor and blocks ET-1 signaling (41). ET-1-mediated FOXO1 redistribution was reversed in the presence of its receptor inhibitor (Fig. 4, J–L).

Fig. 4.

Effect of ET-1 on FoxO1 subcellular distribution. HAEC were cultured in EBM-2 supplemented with 5.6 mm glucose. After 24 h incubation, cells were serum starved for 6 h, followed by incubation in absence (control, A–C) or presence of ET-1 (100 nm) (D–F) in serum/growth factor-free medium for 30 min. As controls, aliquots of cells were treated with insulin (100 nm) (G–I) or ET-1 (100 nm) plus its receptor inhibitor (50 μm) (J–L) in culture medium for 30 min. Each condition was run in triplicate. Cells were subjected to anti-FoxO1 immunocytochemistry. Bar, 10 μm. DAPI, 4′6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

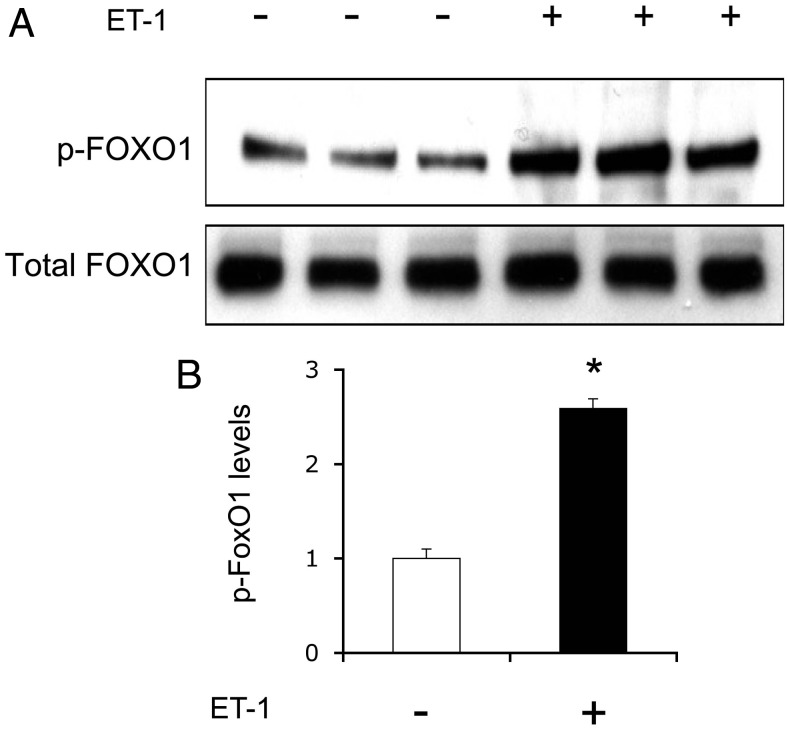

ET-1 promotes FOXO1 phosphorylation in HAEC

To address the mechanism by which ET-1 promoted FOXO1 redistribution from the nucleus to cytoplasm, we determined the ability of ET-1 to promote FOXO1 phosphorylation. Our hypothesis is that ET-1 stimulates phosphorylation of FOXO1, resulting in its nuclear exclusion. Implicit in this hypothesis is the findings that ET-1 functions through the PI3K-AKT axis to regulate its target gene expression (10, 13, 15). To address this hypothesis, we cultured HAEC in the absence or presence of ET-1 (100 nm), followed by an immunoblot analysis of FOXO1 using anti-phospho (S256)-FOXO1 antibody. This assay detected a 2.5-fold induction of FOXO1 phosphorylation in HAEC in response to ET-1 (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

ET-1 mediates FOXO1 phosphorylation. HAEC were transduced with an Adv-FOXO1 vector (100 pfu/cell) in EBM-2 supplemented with 5.6 mm glucose. After 24 h incubation, cells were serum starved for 6 h, followed by incubation in the absence or presence of 100 nm ET-1 for 30 min. Cells were collected for the preparation of total protein lysates, which were analyzed by immunoblot assay using anti-phospho FOXO1 and anti-FOXO1 antibodies (A). The relative abundance of phosphorylated FOXO1 of total FOXO1 proteins in cells was determined (B). Data were from three independent experiments. *, P < 0.001 vs. control.

To determine the ability of ET-1 to promote FOXO1 phosphorylation under hyperglycemic conditions, we cultured HAEC in the presence of 25 mm glucose for 24 h, followed by treatment with ET-1 (100 nm) for 30 min. Cells were subjected to immunoblot assay for detecting phosphorylated and total FOXO1 protein. ET-1-mediated induction of FOXO1 phosphorylation was impaired in the presence of hyperglycemia (Supplemental Fig. 1, published on The Endocrine Society's Journals Online web site at http://mend.endojournals.org).

FOXO1 mediates ET-1 action on endothelial cell survival

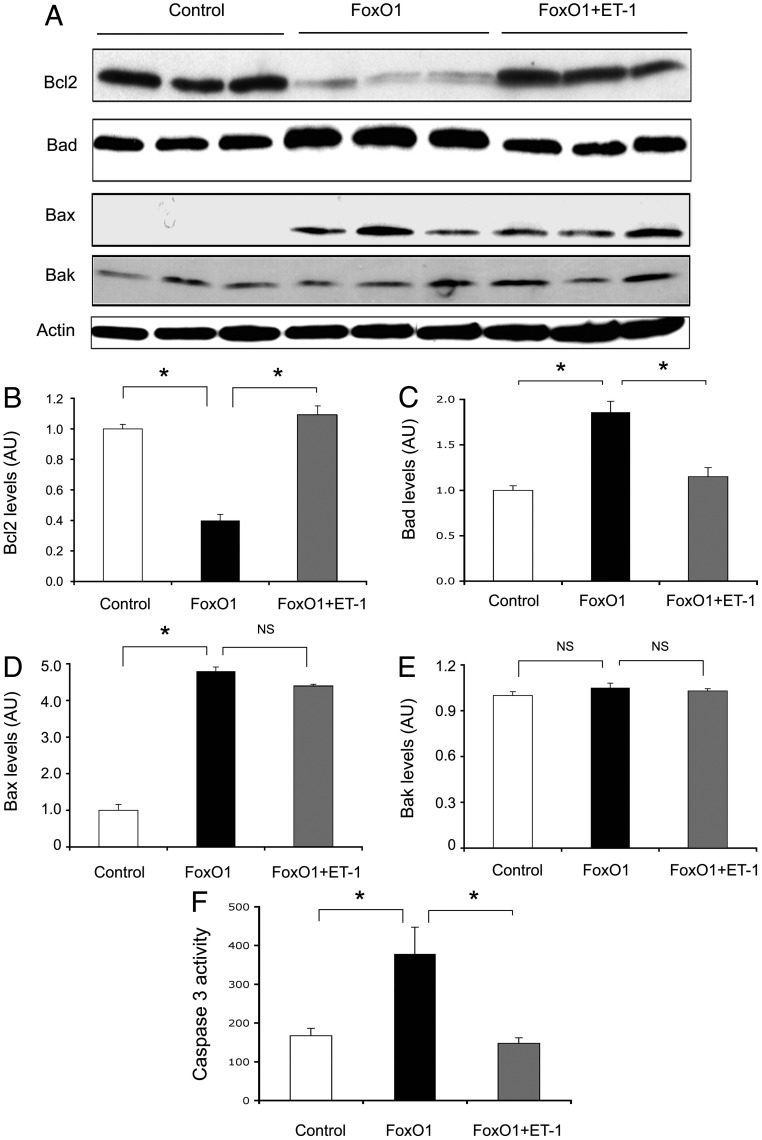

To investigate whether FOXO1 mediates ET-1 action on endothelial cell survival, we determined the impact of FOXO1 on the expression of key functions in cell survival and apoptosis, including BCL-2, BAD, BAX, and BAK. BCL-2 is a prosurvival factor whose expression confers a cytoprotective effect on cell survival (42, 43). In contrast, BAD, BAX, and BAK are associated with proapoptotic activities (44–46). HAEC were transduced with an Adv-FOXO1 vector or a control Adv-null vector at a fixed dose of 100 pfu/cell in the absence or presence of ET-1 (100 nm). After 24 h incubation, cells were subjected to immunoblot analysis (Fig. 6A). Adenovirus-mediated production of FOXO1 resulted in a significant reduction of BCL-2 protein levels in cultured HAEC. This effect was reversed by the addition of ET-1 into culture medium (Fig. 6B). In contrast, the protein levels of BAD and BAX, two important members of the proapoptotic subfamily, were up-regulated in response to FOXO1 production in HAEC (Fig. 6A). Treatment of ET-1 significantly attenuated FOXO1-mediated induction of BAD and BAX production to a greater and lesser extent, respectively, in HAEC (Fig. 6, C and D). In contrast, no significant differences in BAK protein levels were detected in response to FOXO1 production in HAEC, irrespective of the addition of ET-1 into the culture medium (Fig. 6, A and E). These results suggest that FOXO1 contributes to endothelial regulation of BAD production by ET-1 in HAEC.

Fig. 6.

Effect of FOXO1 on endothelial gene expression. HAEC were transduced with a control Adv-null or Adv-FOXO1 vector (100 pfu/cell) in the absence or presence of ET-1 (100 nm). After 24 h incubation, cells were collected for the preparation of total protein lysates, which were subjected to immunoblot analysis (A). The relative protein abundance of BCL-2 (B), BAD (C), BAX (D), and BAK (E) was determined. In addition, aliquots of HAEC were treated with control or FOXO1 vector subjected to caspase-3 activity assay (F). Data were from three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05. NS, Not significant; AU, arbitrary unit.

To corroborate these findings, we determined the effect of FOXO1 on caspase-3 activity in cultured HAEC in response to ET-1 action. HAEC were transduced with a control Adv-null or an Adv-FOXO1 vector in the absence and presence of ET-1 in culture medium. After 24 h incubation, cells were collected for the determination of caspase-3 activity. This assay detected a 2-fold induction of caspase-3 activity in FOXO1 vector-treated HAEC (Fig. 6F). This effect was reversed to normal by the inclusion of ET-1 in culture medium, suggesting that ET-1 signaling through FOXO1 plays an important role in regulating endothelial cell survival.

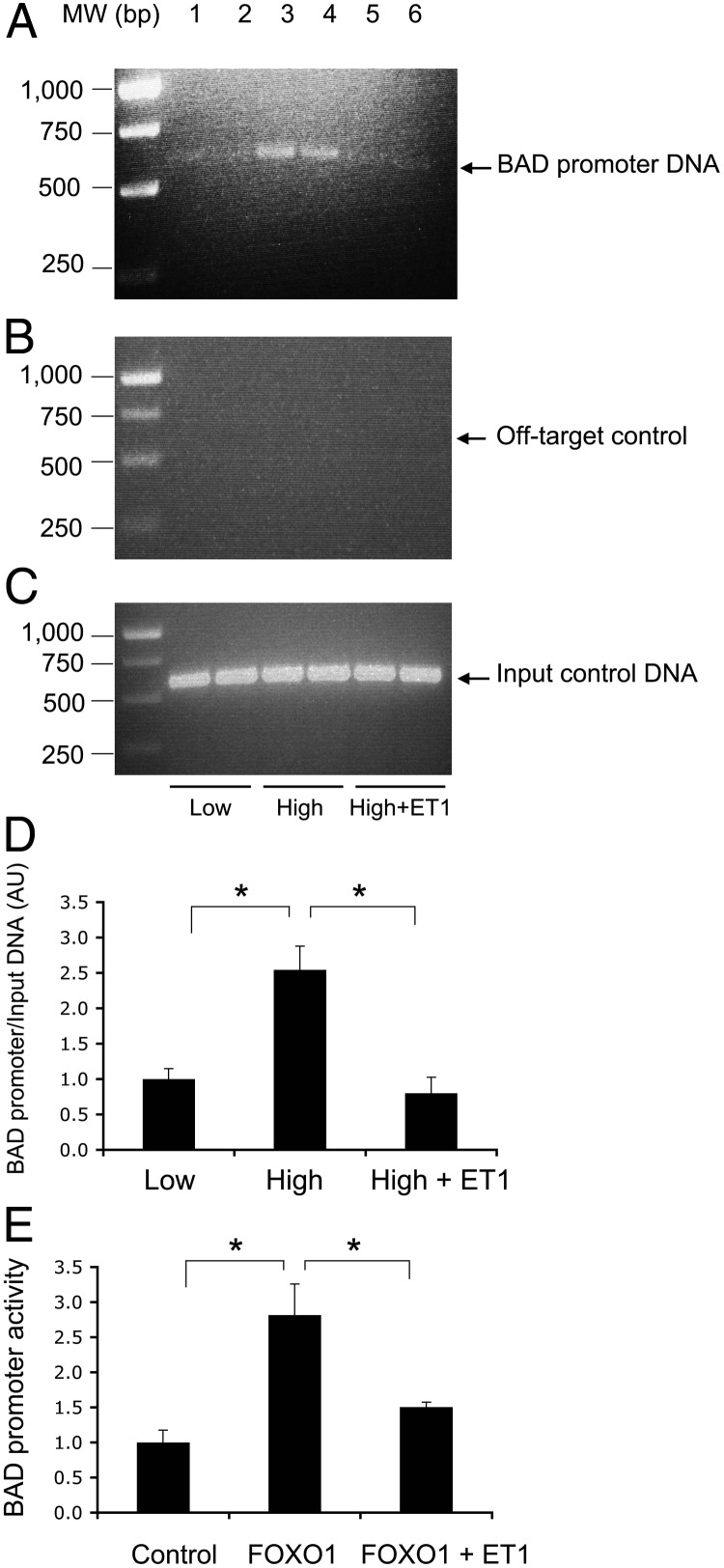

FOXO1 targets BAD gene for trans-activation

To gain insight into the mechanism of FOXO1-mediated induction of endothelial cell apoptosis, we hypothesized that FoxO1 targets the BAD gene for trans-activation. To address this hypothesis, we performed sequence analysis, revealing two consensus FOXO1 binding motifs in the promoter of the BAD gene. Such consensus FOXO1 binding sites are present in the BAD promoter of human and rodent origins (Supplemental Fig. 2), suggesting an evolutionally conserved mechanism by which FOXO1 mediates the effect of ET-1 on endothelial BAD production and cell survival. To determine the molecular association of FOXO1 with the BAD promoter DNA, we performed a ChIP assay on HAEC that were cultured in serum-free medium under normal and higher glucose conditions in the absence or presence of ET-1. This assay allows the detection of protein-DNA interaction in living cells, as described (33, 47). FOXO1 was shown to bind to its target site within the BAD promoter in cultured HAEC under high-glucose conditions, and this effect was abolished by the inclusion of ET-1 in culture medium (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Molecular association of FOXO1 with BAD promoter. HAEC (2 × 106 cells) were cultured under low-glucose (5.6 mm, lanes 1 and 2), high-glucose (25 mm, lanes 3 and 4), and high-glucose (25 mm) plus ET-1 (100 nm) (lanes 5 and 6) conditions. After 24 h incubation, cells were cross-linked with 1% formaldehyde and subjected to a ChIP assay using anti-FOXO1 antibody. The resulting immunoprecipitates were analyzed by PCR using specific primers flanking the FOXO1 target site (−1465/−864 nt) within the BAD promoter (A). MW, Molecular weight. As a negative control, the immunoprecipitates were subjected to PCR analysis using a pair of off-target primers flanking the coding region of BAD cDNA (+721/+1160 nt) (B). As a positive control, aliquots of input DNA samples (10 μl) were used in the same PCR assay (C). The amount of BAD promoter DNA immunoprecipitated by anti-FOXO1 IgG relative to input control DNA was determined (D). In addition, HAEC were cotransfected with pBAD-Luc expressing the BAD promoter-directed Firefly luciferase reporter system and the pGL4.75 expressing the Renilla luciferase gene, followed by transduction with an Adv-FoxO1 or Adv-null vector (100 pfu/cell). After 24 h incubation in serum-free medium with or without ET-1, cells were subjected to a dual-luciferase assay for determining the BAD promoter activity, defined as the ratio of Firefly to Renilla luciferase activities (E). Data were from two independent experiments, each in duplicate. *, P < 0.05 vs. control.

To determine the ability of FoxO1 to trans-activate BAD promoter activity, we cloned the mouse BAD promoter (1.2 kb) into the pGL3-basic vector encoding the Firefly luciferase gene, resulting in plasmid pBAD-Luc. We cotransfected HAEC with pBAD-Luc and pGL4.75 encoding the Renilla luciferase gene as a control, followed by the transduction with the Adv-FOXO1 or control Adv-null vector. After 24 h incubation in serum-free medium in the absence or presence of ET-1, cells were subjected to dual-luciferase activity assay for determining the BAD promoter activity. As shown in Fig. 7, FOXO1 stimulated BAD promoter activity, and this effect was counteracted by ET-1, correlating with the ability of ET-1 to phosphorylate and promote FOXO1 trafficking from the nucleus to the cytoplasm (Fig. 4).

ET-1 protects against hyperglycemia-elicited FOXO1 deregulation in HAEC

To understand the underlying pathophysiology of FOXO1-mediated induction of BAD production in endothelial cells, we incubated HAEC in culture medium supplemented with 5.6 or 25 mm glucose in the absence and presence of ET-1 (100 nm). After 24 h incubation, cells were harvested for the determination of FOXO1 protein levels by immunoblot assay. As shown in Fig. 8, cytosolic FOXO1 protein levels remains unchanged under different conditions. Instead, we detected a 2-fold increase in nuclear FOXO1 protein levels in HAEC under higher glucose conditions, indicating that endothelial FOXO1 expression became deregulated in response to hyperglycemia. This hyperglycemia-induced FOXO1 deregulation was reversed to normal by the addition of ET-1 into culture medium. As control, we subjected HAEC to a real-time quantitative RT-PCR assay. FOXO1 mRNA levels remained unchanged in response to hyperglycemia or ET-1 treatment (Supplemental Fig. 3), consistent with the idea that ET-1 modifies FOXO1 activity at the posttranslational levels.

Fig. 8.

ET-1 inhibits glucose induction of FOXO1 production. HAECs (2 × 106 cells) were cultured in the presence of low (5.6 mm) or high (25 mm) glucose without and with ET-1 addition of 100 nm in culture medium. After 24 h incubation, cells were subjected to immunoblot analysis for the determination of nuclear vs. cytoplasmic FOXO1 levels (A). The relative amounts of FOXO1 proteins in the nucleus and cytoplasm were quantified using actin as control (B). Data were from three independent experiments. *, P < 0.05 vs. control.

Discussion

ET-1 is a potent vasoconstrictor that plays a pivotal role in vascular homeostasis. ET-1 acts via its specific receptors ETA on smooth muscle cells and ETB on endothelial cells to regulate vascular tone and integrity in both autocrine and paracrine manners (1, 2). Although it has been shown that ET-1 also possesses antiapoptotic function (11), the underlying mechanism and physiology is not well understood. In this study, we investigated the mechanisms by which ET-1 exerts its autocrine effect on endothelial cell survival. We studied the effect of ET-1 on endothelial expression of FOXO1 in cultured HAEC as well as in the aortic endothelium of diabetic mice. We show that FOXO1 stimulated the production of BAD, a key proapoptotic protein, via selective binding to the BAD promoter. This effect was accompanied by decreased BCL-2 production and increased caspase-3 activity, contributing to endothelial cell apoptosis in HAEC with unbridled FOXO1 activity. Under hyperglycemic conditions, endothelial FOXO1 activity was significantly up-regulated, culminating in its increased nuclear localization in HAEC. Similar profiles of FOXO1 deregulation were seen in the aorta of hyperglycemic mice. This finding was reproduced in both STZ-induced diabetic mice and genetically diabetic db/db mice. An increased FoxO1 production accounted for its enhanced transcriptional activity, which in turn promoted BAD production and endothelial apoptosis in HAEC. In response to ET-1, FOXO1 became phosphorylated, resulting in FOXO1 trafficking from the nucleus to cytoplasm. This effect contributed to inactivation of FOXO1 activity and suppression of BAD production and inhibition of endothelial cell apoptosis. Although ET-1 exerts its cytoprotective effect on cell survival via the PI3K-Akt cascade (11, 12, 14, 48, 49), the downstream signaling events remain obscure. Our studies suggest that ET-1 signaling through FOXO1 regulates endothelial cell survival.

Endothelial dysfunction secondary to chronic exposure to hyperglycemia contributes to microvascular complications in poorly controlled diabetes, but the underlying mechanism remains obscure. Tanaka et al. (50) showed that FOXO1 activity is significantly up-regulated in endothelial cells in response to hyperglycemia. This effect promotes inducible NO synthase-dependent peroxynitrite generation, which leads to lipid peroxidation and endothelial NO synthase dysfunction. In the present study, we show that FOXO1 underwent O-linked glycosylation in HAEC with prior exposure to hyperglycemia. O-glycosylation is known to interfere with FOXO1 phosphorylation and nuclear export (37, 39, 40). This effect resulted in increased FOXO1 nuclear localization, accounting for its enhanced activity and contributing to the induction of cellular apoptosis in HAEC under hyperglycemic conditions. Such posttranslational modification of FOXO1 has been detected in other cell types, in which O-glycosylation of FOXO1 enhances its transcriptional activity and induces its target gene expression under hyperglycemic conditions (37, 39, 40). Our data together with others suggest that endothelial FOXO1 deregulation, resulting from an impaired ability of ET-1 to keep FOXO1 activity in check, may be a causative factor for the pathogenesis of endothelial dysfunction in diabetes. In support of this notion, Tsuchiya et al. (51) showed that genetic ablation of FOXO1, FOXO3, and FOXO4 genes in the endothelium protected against the development atherosclerosis in low-density lipoprotein receptor deficient mice.

ET-1 synthesis and secretion in endothelial cells is regulated via both the PI3K and MAPK pathways. Two independent studies show that acute treatment of bovine aortic endothelial cells with dehydroepiandrosterone, an adrenal steroid with beneficial effects on insulin sensitivity, results in a marked induction of ET-1 secretion (52, 53). This effect is abolished by the MAPK kinase inhibitor PD98059, suggesting that dehydroepiandrosterone-mediated stimulation of endothelial ET-1 production is via the MAPK-dependent mechanism (52, 53). Likewise, Reiter et al. (54) reported that endothelial ET-1 production is regulated through the PI3k-Akt-FOXO1 signaling pathway. They demonstrate that FOXO1 stimulates ET-1 production in HAEC and this effect is counteracted by green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin gallate, a mechanism that is thought to account for the beneficial effect of epigallocatechin gallate on endothelial function (54–57). Here we show that ET-1 inhibited FOXO1 activity by promoting its phosphorylation and nuclear exclusion. Phosphorylated FOXO1 is targeted for ubiquitination and proteolytic degradation in the cytoplasm (58–60). Together these data illustrate a feedback control mechanism by which endothelial FOXO1 activity is fine-tuned by ET-1. Revelation of the FOXO1 feedback loop in endothelial cells underscores the importance of the ET-1-AKT-FOXO1 axis in endothelial integrity, suggesting that a circuit breakdown in the endothelial FOXO1 feedback loop may be a contributing factor for ET-1 deregulation and endothelial dysfunction in diabetes. Consistent with this conjecture are the observations that endothelial ET-1 production becomes deregulated, culminating in the development of hyperendothelinemia in human subjects with metabolic syndrome (3, 6, 7, 61–64) and animal models with diabetes (5, 65).

We show that FOXO1 was up-regulated at both the mRNA and protein levels in the aorta in the presence of prevailing hyperglycemia in diabetic mice. These in vivo results seemed at odds with in vitro data showing that FOXO1 was regulated in response to hyperglycemia mainly at the posttranslational levels in HAEC. Apart from hyperglycemia in vivo, endothelial cells in the aorta were associated with impaired insulin signaling in diabetic mice. Because FOXO1 is a target of Akt/PKB downstream of insulin action, it is plausible that this discrepancy in endothelial FOXO1 regulation is compounded by altered insulin action in the aorta of diabetic mice. Studies are warranted to further delineate the signaling pathway that governs FOXO1 regulation in endothelial cells.

It is noteworthy that FOXO1 deregulation in the aorta of diabetic mice was reduced, but not to baseline, after insulin therapy. This was presumably attributable to inadequate blood glucose control by insulin therapy in diabetic mice. Attempts with frequent blood glucose monitoring and insulin injection resulted in hypoglycemic episodes, a scenario that is encountered with intensive insulin therapy in clinics. Accordingly, we provided one morning bolus of insulin for controlling postprandial blood glucose excursion, in combination with basal insulin release from the insulin implant that was implanted under the middorsal skin of diabetic mice. Our results provided the proof of concept that FoxO1 deregulation in the aorta of diabetic mice is reversible after the reduction of hyperglycemia with insulin therapy.

In conclusion, we elucidate a mechanism by which ET-1 exerts its autocrine effect on endothelial cell survival. We show that ET-1 acts through AKT/PKB to promote FOXO1 phosphorylation and nuclear exclusion. This effect serves as a fine-tuning mechanism for keeping endothelial FOXO1 activity in check. Deregulation in endothelial FOXO1 production in the aorta may play a role in linking prevailing hyperglycemia to endothelial dysfunction, contributing to microvascular complications in poorly controlled diabetes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Steven Ringquist for critical proofreading of this manuscript. Authors' contributions included the following: V.C., S.L., D.H.K., and A.K. participated in all phases of the studies in cultured HAEC. T.Z., S.S., and S.B. isolated aorta from diabetic mice and performed the studies on aortic FoxO1 expression. P.L. and M.T. contributed to the experimental design and critical discussion of the study. L.P. and H.H.D. designed the study and wrote the manuscript.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant DK087764 (to H.H.D.) and Department of Defense Grant W81XWH-10-1-1055 (to M.T.).

Disclosure Summary: None of the authors in the manuscript has a conflict of interest to declare.

Footnotes

- BAD

- BCL2-antagonist of cell death protein

- BAK

- BCL-2 homologous killer

- BAX

- BCL-2-associated X protein

- BCL-2

- B cell leukemia/lymphoma 2

- ChIP

- chromatin immunoprecipitation

- ET-1

- endothelin 1

- FOXO1

- forkhead box O1

- HAEC

- human aorta endothelial cell

- ICR

- Institute for Cancer Research

- NO

- nitric oxide

- pfu

- plaque-forming unit

- PI3K

- phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- PKB

- protein kinase B

- STZ

- streptozotocin

- TBP

- TATA box binding protein

- WGA

- wheat-germ agglutinin.

References

- 1. Yanagisawa M, Kurihara H, Kimura S, Tomobe Y, Kobayashi M, Mitsui Y, Yazaki Y, Goto K, Masaki T. 1988. A novel potent vasoconstrictor peptide produced by vascular endothelial cells. Nature 332:411–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sakurai T, Yanagisawa M, Takuwa Y, Miyazaki H, Kimura S, Goto K, Masaki T. 1990. Cloning of a cDNA encoding a non-isopeptide-selective subtype of the endothelin receptor. Nature 348:732–735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Seligman BG, Biolo A, Polanczyk CA, Gross JL, Clausell N. 2000. Increased plasma levels of endothelin 1 and von Willebrand factor in patients with type 2 diabetes and dyslipidemia. Diabetes Care 23:1395–1400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Takahashi K, Ghatei MA, Lam HC, O'Halloran DJ, Bloom SR. 1990. Elevated plasma endothelin in patients with diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia 33:306–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wu SQ, Hopfner RL, McNeill JR, Wilson TW, Gopalakrishnan V. 2000. Altered paracrine effect of endothelin in blood vessels of the hyperinsulinemic, insulin resistant obese Zucker rat. Cardiovasc Res 45:994–1000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Piatti PM, Monti LD, Conti M, Baruffaldi L, Galli L, Phan CV, Guazzini B, Pontiroli AE, Pozza G. 1996. Hypertriglyceridemia and hyperinsulinemia are potent inducers of endothelin-1 release in humans. Diabetes 45:316–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Piatti PM, Monti LD, Galli L, Fragasso G, Valsecchi G, Conti M, Gernone F, Pontiroli AE. 2000. Relationship between endothelin-1 concentration and metabolic alterations typical of the insulin resistance syndrome. Metabolism 49:748–752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kohan DE. 2010. Endothelin, hypertension and chronic kidney disease: new insights. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 19:134–139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Versari D, Daghini E, Virdis A, Ghiadoni L, Taddei S. 2009. Endothelial dysfunction as a target for prevention of cardiovascular disease. Diabetes Care 32(Suppl 2):S314–S321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. DeBosch B, Treskov I, Lupu TS, Weinheimer C, Kovacs A, Courtois M, Muslin AJ. 2006. Akt1 is required for physiological cardiac growth. Circulation 113:2097–2104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dong F, Zhang X, Wold LE, Ren Q, Zhang Z, Ren J. 2005. Endothelin-1 enhances oxidative stress, cell proliferation and reduces apoptosis in human umbilical vein endothelial cells: role of ETB receptor, NADPH oxidase and caveolin-1. Br J Pharmacol 145:323–333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pflug BR, Zheng H, Udan MS, D'Antonio JM, Marshall FF, Brooks JD, Nelson JB. 2007. Endothelin-1 promotes cell survival in renal cell carcinoma through the ET(A) receptor. Cancer Lett 246:139–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Del Bufalo D, Di Castro V, Biroccio A, Varmi M, Salani D, Rosanò L, Trisciuoglio D, Spinella F, Bagnato A. 2002. Endothelin-1 protects ovarian carcinoma cells against paclitaxel-induced apoptosis: requirement for Akt activation. Mol Pharmacol 61:524–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nelson JB, Udan MS, Guruli G, Pflug BR. 2005. Endothelin-1 inhibits apoptosis in prostate cancer. Neoplasia 7:631–637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Liu S, Premont RT, Kontos CD, Huang J, Rockey DC. 2003. Endothelin-1 activates endothelial cell nitric-oxide synthase via heterotrimeric G-protein βγ subunit signaling to protein kinase B/Akt. J Biol Chem 278:49929–49935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Accili D, Arden KC. 2004. FoxOs at the crossroads of cellular metabolism, differentiation, and transformation. Cell 117:421–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Barthel A, Schmoll D, Unterman TG. 2005. FoxO proteins in insulin action and metabolism. Trends Endocrinol Metab 16:183–189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Dong XC, Copps KD, Guo S, Li Y, Kollipara R, DePinho RA, White MF. 2008. Inactivation of hepatic Foxo1 by insulin signaling is required for adaptive nutrient homeostasis and endocrine growth regulation. Cell Metab 8:65–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lee SS, Kennedy S, Tolonen AC, Ruvkun G. 2003. DAF-16 target genes that control C. elegans life-span and metabolism. Science 300:644–647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hwangbo DS, Gershman B, Gershman B, Tu MP, Palmer M, Tatar M. 2004. Drosophila dFOXO controls lifespan and regulates insulin signalling in brain and fat body. Nature 429:562–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Puig O, Tjian R. 2006. Nutrient availability and growth: regulation of insulin signaling by dFOXO/FOXO1. Cell Cycle 5:503–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kamagate A, Dong HH. 2008. FoxO1 integrates insulin signaling to VLDL production. Cell Cycle 7:3162–3170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Biggs WH, 3rd, Meisenhelder J, Hunter T, Cavenee WK, Arden KC. 1999. Protein kinase B/Akt-mediated phosphorylation promotes nuclear exclusion of the winged helix transcription factor FKHR1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96:7421–7426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rena G, Prescott AR, Guo S, Cohen P, Unterman TG. 2001. Roles of the forkhead in rhabdomyosarcoma (FKHR) phosphorylation sites in regulating 14-3-3 binding, transactivation and nuclear targetting. Biochem J 354:605–612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Nakae J, Park BC, Accili D. 1999. Insulin stimulates phosphorylation of the forkhead transcription factor FKHR on serine 253 through a wortmannin-sensitive pathway. J Biol Chem 274:15982–15985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Nakae J, Barr V, Accili D. 2000. Differential regulation of gene expression by insulin and IGF-1 receptors correlates with phosphorylation of a single amino acid residue in the forkhead transcription factor FKHR. EMBO J 19:989–996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Durham SK, Suwanichkul A, Scheimann AO, Yee D, Jackson JG, Barr FG, Powell DR. 1999. FKHR binds the insulin response element in the insulin-like growth factor binding protein-1 promoter. Endocrinology 140:3140–3146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Schmoll D, Walker KS, Alessi DR, Grempler R, Burchell A, Guo S, Walther R, Unterman TG. 2000. Regulation of glucose-6-phosphatase gene expression by protein kinase Bα and the Forkhead transcription factor FKHR. J Biol Chem 36324–36333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Zhang X, Gan L, Pan H, Guo S, He X, Olson ST, Mesecar A, Adam S, Unterman TG. 2002. Phosphorylation of serine 256 suppresses transactivation by FKHR (FOXO1) by multiple mechanisms. Direct and indirect effects on nuclear/cytoplasmic shuttling and DNA binding. J Biol Chem 277:45276–45284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Van Der Heide LP, Hoekman MF, Smidt MP. 2004. The ins and outs of FoxO shuttling: mechanisms of FoxO translocation and transcriptional regulation. Biochem J 380:297–309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Luppi P, Cifarelli V, Tse H, Piganelli J, Trucco M. 2008. Human C-peptide antagonises high glucose-induced endothelial dysfunction through the nuclear factor-κB pathway. Diabetologia 51:1534–1543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kwok CF, Juan CC, Ho LT. 2007. Endothelin-1 decreases CD36 protein expression in vascular smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 292:E648–E652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kamagate A, Qu S, Perdomo G, Su D, Kim DH, Slusher S, Meseck M, Dong HH. 2008. FoxO1 mediates insulin-dependent regulation of hepatic VLDL production in mice. J Clin Invest 118:2347–2364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Altomonte J, Cong L, Harbaran S, Richter A, Xu J, Meseck M, Dong HH. 2004. Foxo1 mediates insulin action on ApoC-III and triglyceride metabolism. J Clin Invest 114:1493–1503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Su D, Zhang N, He J, Qu S, Slusher S, Bottino R, Bertera S, Bromberg J, Dong HH. 2007. Angiopoietin-1 production in islets improves islet engraftment and protects islets from cytokine-induced apoptosis. Diabetes 56:2274–2283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kim DH, Perdomo G, Zhang T, Slusher S, Lee S, Phillips BE, Fan Y, Giannoukakis N, Gramignoli R, Strom S, Ringquist S, Dong HH. 2011. Forkhead box O6 integrates insulin signaling with gluconeogenesis in the liver. Diabetes 60:2763–2774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kuo M, Zilberfarb V, Gangneux N, Christeff N, Issad T. 2008. O-glycosylation of FoxO1 increases its transcriptional activity towards the glucose 6-phosphatase gene. FEBS Lett 582:829–834 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Qu S, Altomonte J, Perdomo G, He J, Fan Y, Kamagate A, Meseck M, Dong HH. 2006. Aberrant Forkhead box O1 function is associated with impaired hepatic metabolism. Endocrinology 147:5641–5652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Kuo M, Zilberfarb V, Gangneux N, Christeff N, Issad T. 2008. O-GlcNAc modification of FoxO1 increases its transcriptional activity: a role in the glucotoxicity phenomenon? Biochimie 90:679–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Housley MP, Rodgers JT, Udeshi ND, Kelly TJ, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF, Puigserver P, Hart GW. 2008. O-GlcNAc regulates FoxO activation in response to glucose. J Biol Chem 283:16283–16292 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Urade Y, Fujitani Y, Oda K, Watakabe T, Umemura I, Takai M, Okada T, Sakata K, Karaki H. 1992. An endothelin B receptor-selective antagonist: IRL 1038, [Cys11-Cys15]-endothelin-1(11-21). FEBS Lett 311:12–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Liu C, Liang B, Wang Q, Wu J, Zou MH. 2010. Activation of AMP-activated protein kinase α1 alleviates endothelial cell apoptosis by increasing the expression of anti-apoptotic proteins Bcl-2 and survivin. J Biol Chem 285:15346–15355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 43. Hockenbery DM, Oltvai ZN, Yin XM, Milliman CL, Korsmeyer SJ. 1993. Bcl-2 functions in an antioxidant pathway to prevent apoptosis. Cell 75:241–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Oltvai ZN, Milliman CL, Korsmeyer SJ. 1993. Bcl-2 heterodimerizes in vivo with a conserved homolog, Bax, that accelerates programmed cell death. Cell 74:609–619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Danial NN. 2008. BAD: undertaker by night, candyman by day. Oncogene 27(Suppl 1):S53–S70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Lalier L, Cartron PF, Juin P, Nedelkina S, Manon S, Bechinger B, Vallette FM. 2007. Bax activation and mitochondrial insertion during apoptosis. Apoptosis 12:887–896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Kamagate A, Kim DH, Zhang T, Slusher S, Gramignoli R, Strom SC, Bertera S, Ringquist S, Dong HH. 2010. FoxO1 links hepatic insulin action to endoplasmic reticulum stress. Endocrinology 151:3521–3535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Schorlemmer A, Matter ML, Shohet RV. 2008. Cardioprotective signaling by endothelin. Trends Cardiovasc Med 18:233–239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Sumitomo M, Milowsky MI, Shen R, Navarro D, Dai J, Asano T, Hayakawa M, Nanus DM. 2001. Neutral endopeptidase inhibits neuropeptide-mediated transactivation of the insulin-like growth factor receptor-Akt cell survival pathway. Cancer Res 61:3294–3298 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Tanaka J, Qiang L, Banks AS, Welch CL, Matsumoto M, Kitamura T, Ido-Kitamura Y, DePinho RA, Accili D. 2009. Foxo1 links hyperglycemia to LDL oxidation and endothelial nitric oxide synthase dysfunction in vascular endothelial cells. Diabetes 58:2344–2354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Tsuchiya K, Tanaka J, Shuiqing Y, Welch CL, DePinho RA, Tabas I, Tall AR, Goldberg IJ, Accili D. 2012. FoxOs integrate pleiotropic actions of insulin in vascular endothelium to protect mice from atherosclerosis. Cell Metab 15:372–381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Formoso G, Chen H, Kim JA, Montagnani M, Consoli A, Quon MJ. 2006. Dehydroepiandrosterone mimics acute actions of insulin to stimulate production of both nitric oxide and endothelin 1 via distinct phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase- and mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent pathways in vascular endothelium. Mol Endocrinol 20:1153–1163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Chen H, Lin AS, Li Y, Reiter CE, Ver MR, Quon MJ. 2008. Dehydroepiandrosterone stimulates phosphorylation of FoxO1 in vascular endothelial cells via phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase- and protein kinase A-dependent signaling pathways to regulate ET-1 synthesis and secretion. J Biol Chem 283:29228–29238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Reiter CE, Kim JA, Quon MJ. 2010. Green tea polyphenol epigallocatechin gallate reduces endothelin-1 expression and secretion in vascular endothelial cells: roles for AMP-activated protein kinase, Akt, and FOXO1. Endocrinology 151:103–114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Potenza MA, Marasciulo FL, Tarquinio M, Tiravanti E, Colantuono G, Federici A, Kim JA, Quon MJ, Montagnani M. 2007. EGCG, a green tea polyphenol, improves endothelial function and insulin sensitivity, reduces blood pressure, and protects against myocardial I/R injury in SHR. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 292:E1378–E1387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Widlansky ME, Hamburg NM, Anter E, Holbrook M, Kahn DF, Elliott JG, Keaney JF, Jr, Vita JA. 2007. Acute EGCG supplementation reverses endothelial dysfunction in patients with coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Nutr 26:95–102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ou HC, Song TY, Yeh YC, Huang CY, Yang SF, Chiu TH, Tsai KL, Chen KL, Wu YJ, Tsai CS, Chang LY, Kuo WW, Lee SD. 2010. EGCG protects against oxidized LDL-induced endothelial dysfunction by inhibiting LOX-1-mediated signaling. J Appl Physiol 108:1745–1756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Matsuzaki H, Daitoku H, Hatta M, Tanaka K, Fukamizu A. 2003. Insulin-induced phosphorylation of FKHR (Foxo1) targets to proteasomal degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100:11285–11290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Aoki M, Jiang H, Vogt PK. 2004. Proteasomal degradation of the FoxO1 transcriptional regulator in cells transformed by the P3k and Akt oncoproteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:13613–13617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Huang H, Regan KM, Wang F, Wang D, Smith DI, van Deursen JM, Tindall DJ. 2005. Skp2 inhibits FOXO1 in tumor suppression through ubiquitin-mediated degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:1649–1654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Gogg S, Smith U, Jansson PA. 2009. Increased MAPK activation and impaired insulin signaling in subcutaneous microvascular endothelial cells in type 2 diabetes: the role of endothelin-1. Diabetes 58:2238–2245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Desideri G, Ferri C, Bellini C, De Mattia G, Santucci A. 1997. Effects of ACE inhibition on spontaneous and insulin-stimulated endothelin-1 secretion: in vitro and in vivo studies. Diabetes 46:81–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Letizia C, Iannaccone A, Cerci S, Santi G, Cilli M, Coassin S, Pannarale MR, Scavo D, Iannacone A. 1997. Circulating endothelin-1 in non-insulin-dependent diabetic patients with retinopathy. Horm Metab Res 29:247–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Kawamura M, Ohgawara H, Naruse M, Suzuki N, Iwasaki N, Naruse K, Hori S, Demura H, Omori Y. 1992. Increased plasma endothelin in NIDDM patients with retinopathy. Diabetes Care 15:1396–1397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Wilkes JJ, Hevener A, Olefsky J. 2003. Chronic endothelin-1 treatment leads to insulin resistance in vivo. Diabetes 52:1904–1909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.