Abstract

Exploitation of the relationship between estrogen receptor (ER) structure and activity has led to the development of 1) selective ER modulators (SERM), compounds whose relative agonist/antagonist activities differ between target tissues; 2) selective ER degraders (SERD), compounds that induce a conformational change in the receptor that targets it for proteasomal degradation; and 3) tissue-selective estrogen complexes (TSEC), drugs in which a SERM and an ER agonist are combined to yield a blended activity that results in distinct clinical profiles. In this study, we have performed a comprehensive head-to-head analysis of the transcriptional activity of these different classes of ERM in a cellular model of breast cancer. Not surprisingly, these studies highlighted important functional differences and similarities among the existing SERM, selective ER degraders, and TSEC. Of particular importance was the identification of genes that were regulated by various TSEC combinations but not by an estrogen or SERM alone. Cumulatively, the findings of this analysis are informative with respect to the mechanisms by which ER is engaged by different enhancers/promoters and highlights how promoter context influences the pharmacological activity of ER ligands.

The estrogen receptor (ER) is a ligand-dependent transcription factor, whose expression confers upon target cells the ability to respond to estrogens. In the absence of an activating ligand, ER resides in the cell in an inactive form within a large inhibitory protein complex. Upon binding ligand, however, the receptor undergoes an activating conformational change, resulting in its release from the inhibitory protein complex, spontaneous dimerization, and subsequent interaction with enhancers located within target genes (1). Depending on the promoter context of the bound receptor, and the cofactors that are recruited to the receptor in a particular cell, it can either positively or negatively regulate target gene transcription. Thus, the same ER-ligand complex can have very different activities in different cells, an observation that explains how estrogens, generally considered to be reproductive hormones, exhibit activities in bone, the cardiovascular system, and in brain that are unrelated to reproductive function (2–4).

Although the molecular determinants of ER action in different target cells are numerous, it was anticipated that the exploitation of this complexity would yield pharmaceuticals with process or tissue-selective activities. Indeed, the first evidence in support of this hypothesis came from studies that probed the pharmacological activities of the “antiestrogen” tamoxifen. Identified as a high-affinity antagonist of ER and developed as a treatment for ER-positive breast cancer, it soon became apparent that although tamoxifen could oppose estrogen action in the breast, it exhibited agonist activity in the bone, uterus, and in the cardiovascular system (5–8). Reflecting this spectrum of activities, tamoxifen was reclassified as a selective ER modulator (SERM) (9). Indeed, were it not for the undesirable agonist activity of tamoxifen in the uterus, it would likely have had potential utility in the treatment/prevention of osteoporosis. However, the profile of tamoxifen encouraged the empirical testing of other antiestrogens for SERM activity, and it was in this manner that it was determined that keoxifene [later renamed raloxifene (Ral)] exhibited the positive attributes of tamoxifen absent significant uterotrophic activities (10, 11). This drug is now approved for the treatment and prevention of osteoporosis, and based on the recent results of the Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene (STAR) trial, it is apparent also that it also has utility as a breast cancer preventative (12). Thus, without knowledge of the molecular mechanisms that determine ER pharmacology, two SERM with clinically useful activities emerged.

Driven by the interest in developing SERM with improved therapeutic profiles and by the need to understand the molecular mechanisms underlying tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer, there has been significant interest in defining the molecular basis for the pharmacological activity of ER ligands. From these studies, it is clear that the response of a cell to an ER ligand is influenced by 1) the relative and absolute expression level of each of the two functionally distinct ER (ERα and ERβ), 2) the overall conformation adopted by ER upon ligand binding, 3) the impact that receptor conformation has on its interaction with coregulators, 4) the activity and absolute expression of functionally distinct coregulators in target cells, and 5) the impact of processes in the cells that interface with and modulate the activity of different ER-coregulator complexes (13–20). Importantly, these insights have enabled the development of mechanism-based screens for novel SERM, an exercise that has yielded lasofoxifene (Laso) and bazedoxifene acetate (BZA), molecules which, not unexpectedly, exhibit a spectrum of clinical activities distinct from tamoxifen or Ral (21, 22).

Although the currently available SERM exhibit useful activity in bone, it is their specific ability to decrease the incidence of breast cancer in women at elevated risk for the disease that is most important. However, the currently available SERM do not treat the climacteric symptoms associated with menopause/estrogen deprivation and indeed generally exacerbate these conditions, a liability that is a significant impediment to their widespread use as breast cancer preventatives (23, 24). Unfortunately, despite our advanced understanding of ER pharmacology, it is not readily apparent as yet if it will be possible to develop a SERM that has the ideal clinical profile. However, considering the differential sensitivities of various target organs to estrogens and the spectrum of activities of available SERM, it has been suggested that by combining a classical estrogen with a SERM in a single medicine that it might be possible to develop a more clinically useful ER modulator (25). Given that SERM exhibit different activities in different cells and likewise that structurally similar steroidal estrogens can exhibit different activities, it is likely that the combination of different estrogens with different SERM will result in the development of drugs with very different pharmacological activities. Thus far, two medicines of this type, now considered to be members of the tissue-selective estrogen complex (TSEC) class of drugs [17β estradiol (E2)/Ral and conjugated estrogens/BZA], have been evaluated in postmenopausal women, and although not compared in a head-to-head manner, they were found to exhibit different clinical activities (26, 27).

Thus, this study was undertaken with the goal of defining the complexity of the transcriptional responses to different SERM in cellular models of breast cancer and how these responses were influenced by E2 and vice versa. These studies revealed an unexpected complexity in the cellular response to different SERM and demonstrated that even within the same cells, dramatically different responses to structurally different SERM are apparent. Furthermore, we determined that, in addition to the expected attenuation of the agonist activities of estrogens, transcriptional responses unique to specific E2/SERM combinations were identified. This latter finding is particularly instructive with respect to the activity of TSEC and may also explain why the biology of tamoxifen is not equivalent in pre- and postmenopausal women. Although the primary objective of this study was to explore the transcriptional consequences of the conformational changes in ER that occur upon binding different SERM, the results also provide a robust atlas of SERM action that we believe will be a useful resource to the field.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

ER ligands included E2 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), ICI 182,780 (ICI) (Tocris, Ellisville, MO), 4-hydroxytamoxifen (4OHT) (Sigma), and Ral, BZA, and Laso (all generously provided by Wyeth; now Pfizer, New York, NY). Ligands were dissolved in ethanol or dimethylsulfoxide.

Cell culture

MCF7 and SKBR3 breast cancer cell lines were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and were maintained in DMEM/F12 or RPMI 1640 media, respectively (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), supplemented with 8% fetal bovine serum (Sigma), nonessential amino acids (Invitrogen), and sodium pyruvate (Invitrogen). Cells were plated for experiments in the same media lacking phenol red and supplemented with 8% charcoal-stripped fetal bovine serum.

Transfection and mammalian two-hybrid analysis

SKBR3 cells were plated in 96-well culture plates at a density of 1.2 × 104 cells/well and then were transfected using Lipofectin (per manufacturer's instructions; Invitrogen) with plasmids expressing a Gal4DBD-peptide fusion construct (45 ng/well) or VP16-fused ER (45 ng/well) together with 5XGal-ERE (45 ng/well) and 10 ng/well of a plasmid expressing cytomegalovirus-controlled β-galactosidase as an internal control. Ligands were added 4 h after transfection without changing the media. After 20 h of treatment, cells were harvested, and whole-cell lysates were analyzed for detection of luciferase and β-galactosidase activity as previously described (20). Gal4DBD lacking a fused peptide and the empty VP16 fusion vector were used as controls. All plasmids have been previously described (20).

RNA production, DNA microarray, and real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

MCF7 cells were plated in six-well culture dishes at a density of 4 × 105 cells/well; 48 h after plating, cells were treated with ER ligands using 1 nm final concentration vehicle (ethanol) or E2 in the presence or absence of vehicle (dimethylsulfoxide) or SERM (100 nm). After 24 h of treatment, cells were washed once in PBS before lysis. RNA isolation (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) and reverse transcription (iScript; Bio-Rad) were performed per kit manufacturer's instructions. RT-qPCR of cDNA was done using iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) per kit instructions and performed using the Bio-Rad CFX384 real-time system with associated software (Bio-Rad) and using a C1000 thermal cycler (Bio-Rad). mRNA abundance was calculated using the ΔΔCT method as previously described (28). Samples analyzed by microarray were drawn from 10 independently produced sets that each included all experimental conditions, with the exception of Laso and Laso/E2 treatments, which were done in triplicate. For quality control purposes, ligand-dependent regulation of ER target genes TFF1 (responsive only to agonist) and RET (SERM induced) were analyzed by RT-qPCR analysis of those samples intended for microarray analysis before submission. Probe preparation and hybridization to Human 133 Plus 2.0 Chips (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA) were performed at Duke Microarray Facility. Probe-level processing and analysis was performed in JMP Genomics 4.0 (SAS, Cary, NC). Probe set intensities were log2-transformed, background normalized by robust multi-chip average adjusted for GC-content (GC-RMA) with quantile normalization, and summarized by median polish. Batch effects related to the chronological order of sample generation were removed by distance-weighted discrimination (29) implemented in Matlab (Mathworks, Natick, MA). Significant changes in gene expression were detected by one-way ANOVA on the treatment variable. Family-wise error rate was controlled by Holm correction at α level of 0.05. Very low-intensity probe sets, as well as probe sets whose intensities do not vary significantly among the sample means, were removed by filtering at lower 2 sd cutoff for individual sample intensity values, and at lower 5% of sd of the group means. Validation of genes regulated in the microarray analysis was performed using at least three separately produced sets of samples produced from MCF7 cells treated and harvested as above. Sequences of primers used for RT-qPCR validation of regulated genes are available upon request. Microarray data have been deposited to NCBI GEO with accession no. GSE35428.

Results

SERM, estradiol, and ICI induce distinct conformations of ER

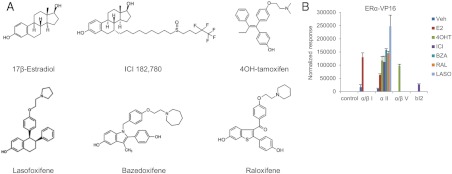

The primary goal of this study was to evaluate the pharmacological properties of a series of clinically relevant SERM and define how the activities of these drugs were influenced by coadministration of the agonist E2. Included in this analysis were the SERM 4OHT, BZA, Ral, and Laso. For comparative purposes, we also profiled the selective ER degrader (SERD) (ICI), a compound that functions as a full ER antagonist (see Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

ER ligands differ in their structures and in their associated ER conformations. A, Chemical structures of the ER ligands used in the analysis. B, Interaction between ER and conformation-specific peptides in mammalian two-hybrid system. Triplicate wells of SKBR3 cells were transfected with plasmids expressing ERα fused to VP16 together with Gal4DBD alone (control) or fused to ER-interacting peptides noted on the horizontal axis. Cells were then treated with the indicated ER ligands (100 nm). Interaction of ER with the Gal4DBD peptide constructs was detected through activation of a Gal4-responsive luciferase reporter construct and was normalized to detected β-galactosidase activity generated by a cotransfected constitutive expression vector. Normalized response is expressed as fold increase over the detected level of interaction between Gal4DBD alone and ER-VP16 in the absence of ligand vehicle (Veh). Data are representative of at least three independent experiments.

Receptor conformation has emerged as a major determinant of the pharmacological activity of ER ligands. Thus, we first undertook an evaluation of the impact of the selected ligands on the overall structure of the receptor in the context of the intact cell. Previously, we have reported on the identification, using combinatorial peptide phage display, of a series of 19-mer peptides whose ability to interact with ERα within the cell is influenced by the nature of the bound ligand (20). By assessing the differential interaction of these peptides with ERα, it is possible to get an appreciation of the impact of specific ligands on receptor structure. Specifically, the peptide probes are synthesized within cells as fusions with the heterologous Gal4 DBD, and their ability to recruit a VP16-ERα fusion protein is assessed using a Gal4RE-luciferase reporter. For this assay, we selected a series of peptide probes that interact with ERα 1) in the presence of agonist (α/βI), 2) bound to any ligand (αII), 3) only when occupied by 4OHT (α/βV), or 4) in the presence of ICI (bI2). The peptide interaction profiles observed in cells treated with different ligands is shown in Fig. 1B and reveals that the conformation(s) adopted by ER when occupied by BZA, Ral, or Laso are distinct from that observed when the receptor is occupied by E2, 4OHT, or ICI (Fig. 1B). Therefore, although all of the SERM tested efficiently inhibited E2-mediated activation of several classical ER target genes (data not shown), they allowed the receptor to adopt different conformations and thus had the potential to facilitate the assembly of different ER-coregulator complexes. Thus, it was anticipated that when assayed at the whole transcriptome level, the SERM would be functionally distinguishable.

Comparison of SERM-induced transcriptomes in a cellular model of breast cancer

To evaluate and compare the functional activities of the selected SERM, we performed a head-to-head comparison of the impact of each drug on gene transcription in the ER-positive MCF-7 cell line. For these studies, cells were treated for 24 h with 1) each SERM alone (100 nm) or 2) each SERM (100 nm) in the presence of E2 (1 nm). We also examined gene transcription in cells treated with ICI or E2 alone or in the presence of both drugs combined. A 24-h time point was selected to evaluate gene expression profiles that reflected the steady-state response of cells to SERM, rather than acute effects that were more likely going to reflect in large part simple antagonism of ER activation. It is important to note that, with the exception of the studies performed with Laso (three biological replicates), 10 completely independent biological replicates were performed. This provided us with the statistical power to identify subtle changes in the expression of potentially important target genes. For all treatments, we evaluated gene expression using Affymetrix HG-133 Plus 2.0 Chips.

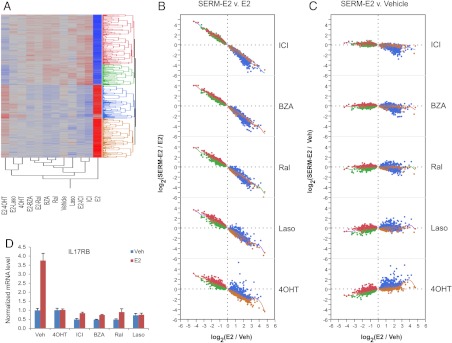

As an initial step in this analysis, an ANOVA comparing gene expression events observed with each treatment to every other treatment was performed. In this manner, 10,389 probe sets (representing 7171 unique transcripts) satisfied the significance criteria in at least one comparison, a result that highlights the complexity of ER pharmacology. As expected, and as is apparent from the clustering diagram presented in Fig. 2, the majority of genes whose expression was modulated by at least one SERM were also regulated by estradiol (the intensities of 7147 probe sets are significantly changed in the E2 vs. vehicle (Veh) comparison). The notable exception is the identification of a significant number of genes that are induced by 4OHT but whose expression is not modulated by E2. It is also clear from this analysis that the expression of nearly all of the E2-regulated genes are attenuated by the addition of a SERM. However, the differences in the relative agonist/antagonist activities of the individual SERM on E2-regulated genes is a very obvious distinguishing feature of these ligands.

Fig. 2.

Analysis of expression of 10,389 probe sets significantly regulated by ICI, Ral, BZA, Laso, 4OHT, or their combinations with estradiol by hierchical clustering.

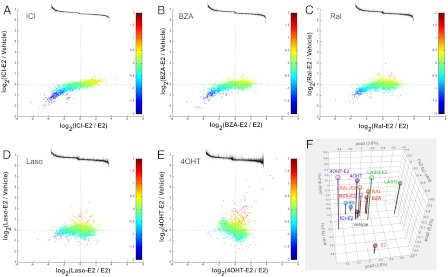

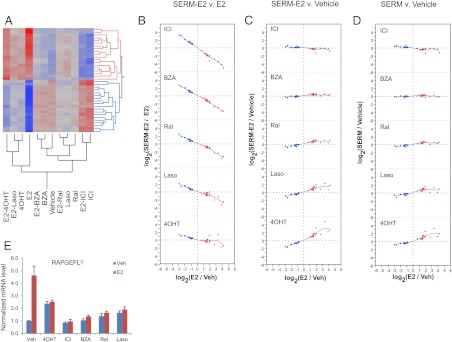

The relationship between SERM and E2 activities is illustrated in Fig. 3. In Fig. 3, A–E, the two planar dimensions describe the impact of each individual SERM on E2-induced transcription. The difference between expression level in the presence of SERM-E2 combination and in the presence of E2 alone is plotted on the horizontal axis. In the context of the agonist-antagonist relationship, the genes to the right of the zero mark are those that are repressed by E2 and on which repression is relieved by addition of a SERM; conversely, the genes to the left of the zero mark are those that are induced by E2, and this induction is opposed by a SERM. On the vertical axis, the difference between the expression level in the presence of SERM-E2 combination and that in the presence of vehicle is plotted. Proximity of a point to the horizontal zero line indicates that the activity of E2 is completely negated by addition of a SERM. Within the framework of the agonist-antagonist relationship between SERM and E2, the first and third quadrants would correspond to inverse agonist activity on E2-repressed and E2-induced genes, respectively, whereas the second and fourth quadrants would correspond to partial agonist activity. The color of the data points corresponds to the effects of a SERM on the basal transcription level independent of E2. These panels illustrate an evolution of the spectrum of SERM activities from solely E2 dependent and antagonistic to more E2 independent and agonistic in the order of ICI, BZA, Ral, Laso, and 4OHT. Indeed, looking at ICI activities, we observe an exclusively antagonistic relationship with E2, with a significant tendency to inhibit the activities of E2 below the basal level (Fig. 3A). When analyzed in the same manner, it was determined that with BZA and Ral (Fig. 3, B and C, respectively), a gradual weakening of the inverse agonist properties is observed. In contrast, we begin to observe an appearance of a small group of genes that are up-regulated by Ral independent of its action on E2-stimulated transcription (red markers, first and fourth quadrants). With Laso and 4OHT, an almost complete disappearance of inverse agonist activity is observed, with the appearance of classical partial agonist activity becoming apparent (Fig. 3, D and E, respectively). Finally, and most importantly, we observe a distinct group of genes for which expression levels in the presence of E2–4OHT combination is greater than that in the presence of E2 or vehicle; these genes are also regulated by 4OHT alone. The activity manifest on these genes is unique to 4OHT and suggests a mechanistically distinct mode of action for this ligand.

Fig. 3.

Relationship between E2-dependent and E2-independent activities of SERM. A–E, Each point represents a probe set selected as described in the text. Abscissa and ordinate axes represent differences in gene expression in the presence of SERM-E2 combination and E2 and vehicle, respectively. Dot color represents difference between gene expression in the presence of SERM and in the presence of vehicle; red indicates up-regulation by SERM, blue indicates down-regulation. Color scale is clipped at ±2. Insets, Extent of E2 sensitivity. Probe sets were arranged from left to right in the same order as they appear on the scatter plots, and the extent of E2 regulation was plotted on the ordinate axis. F, PC analysis (PCA) based on standardized group means and 10,389 probe sets selected as being significantly changed between treatments. Additional projections of the expression data are presented in Supplemental Fig. 1.

The differences between SERM can be further illustrated using principal component (PC) analysis (Fig. 3F). In this analysis, the first PC, which contains most of the variance, establishes the distance between E2 and vehicle and places all SERM on this scale, whereas the second PC, which contains about 8% of total variance, explains for the most part the differences between SERM and vehicle. Finally, the third PC is dominated, surprisingly, by the differences among SERM. Cumulatively, this analysis highlights the pharmacological complexity of ER ligands, a finding that likely reflects the differential effects of these compounds on ER structure.

Defining the pharmacological complexity of SERM

By definition, SERM have the ability to manifest different activities in different cells, a consequence, it is believed, of differential cofactor recruitment by ER-ligand complexes. However, by focusing on differences in the regulation of gene expression in the same cell, we have the opportunity to define the cell autonomous factors (i.e. promoter architecture) that influence SERM responsiveness. The analysis presented here uncovers large groups of genes that display preferential transcriptional responses to closely related antiestrogens and creates an inventory of E2-dependent and E2-independent activities of SERM. To construct a comprehensive data matrix linking ligands to global transcriptional responses, we classified each probe set according to whether its intensity is 1) different between the E2-induced state and the combination of E2 and any given SERM, 2) different between the baseline state (vehicle) and in the presence of E2 plus any given SERM, and 3) different between baseline and in the presence of any given SERM. Examining the response of each gene to each SERM, according to these criteria, allowed the broad definition of the compound-gene effector-target relationships, with distinct and overlapping parts. For the sake of presentation, these relationships can be grouped by the dominant activities of ligands.

1) Competitive antagonist activity of SERM

As expected, SERM function as competitive antagonists on most of the genes examined. The E2-regulated expression of these genes is brought back to the baseline level by at least one of the SERM, because these drugs have no activity on these targets in the absence of E2. The relationship among SERM when evaluated on this class of genes is illustrated on Fig. 4. The data presented in Fig. 4, B and C, represent the fold change in the intensity of each probe set under the conditions of the comparisons. Presentation in this manner allows a qualitative analysis of 1) the impact of each SERM on E2 action (Fig. 4B), and 2) the degree to which each compound restores E2-mediated transcriptional activity to the basal state (Fig. 4C). For each graph, fold change with E2 treatment alone vs. vehicle (E2 induction or repression) is represented on the horizontal axis, whereas fold change in gene expression upon the addition of a SERM/E2 combination or SERM alone is indicated on the vertical axis. The colors used to plot the expression of each gene correspond to their initial classification in the clustering diagram shown in Fig. 4A. On the majority of these genes (6199 of 6934 probe sets), E2 activity is completely reversed by ICI; exceptions are likely to be due to formal thresholding, rather than a presence of a mechanistically distinct class, as indicated by hierarchical clustering (Fig. 4A). Ral and BZA closely mimic the behavior of ICI on these genes. In contrast, 4OHT, despite been studied at concentrations that totally saturate the receptor, exhibits full antagonist activity on only a subset of genes within this class (4185 of 6934 probe sets). The relatively weak antagonist activity observed is particularly evident on the genes included in the blue cluster (E2 activated) and green clusters (E2 repressed). The effect of Laso on most of these genes is found to be intermediate between that observed in cells treated with 4OHT and those treated with ICI/Ral/BZA. Importantly, a defining characteristic of this class is that the expression level of genes in the presence of E2 together with at least one SERM is not distinguishable from the basal state, a characteristic that distinguishes antagonism from inverse agonism. Note that although the expression level of many genes in this cluster is inhibited below the level of vehicle, especially by ICI, the extent of this inhibition does not reach statistical significance (data not shown). An example of a gene from this class is IL17RB, whose expression profile is illustrated in Fig. 4D. As expected, functional annotation of this list of genes revealed strong overrepresentation of gene ontology (GO) terms relevant to mitosis and cell cycle progression (see Supplemental Tables 1–9, published on The Endocrine Society's Journals Online web site at http://mend.endojournals.org).

Fig. 4.

Analysis of expression of 6934 probe sets reporting on genes for which the effects of estradiol are completely inhibited by at least one of the tested compounds. A, Clustering diagram. B and C, Bivariate plots showing the extent of regulation, expressed as the log2-transformed ratio of intensities, for SERM-E2 vs. E2 and SERM-E2 vs. vehicle comparisons, respectively. Dashed lines indicate the log-ratio of zero (no change). Smoother lines (running mean) are included on the bivariate plots. D, Expression profile of a representative gene from this class, IL17RB obtained in an independent experiment, as determined by qPCR. For additional data, see Supplemental Fig. 2.

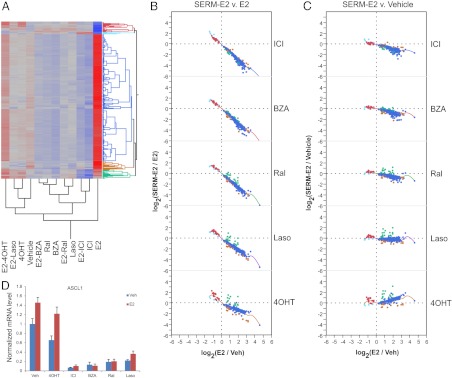

2) Inverse agonist activity of SERM

One important difference between the SERM that was revealed in this study is the degree to which they exhibit inverse agonist activity on some target genes. Specifically, the genes contained in this class are positively or negatively regulated by E2, but cotreatment with E2 and at least one SERM brings the expression level below the basal level (or above basal level in the case of E2-down-regulated genes). By these criteria, we identified 255 transcripts represented by 329 probe sets, on which at least one SERM exhibits inverse agonist activity. The analysis of the expression of genes in this class is highlighted in Fig. 5A. Not surprisingly, ICI functions as an inverse agonist on the majority of genes (288 out of 329 probe sets) in this class. Unexpectedly, however, was the extent to which BZA and Ral phenocopied ICI, although with somewhat less efficacy (Fig. 5, B and C). On the majority of genes in this class, neither 4OHT nor Laso exhibited inverse agonist activity (Fig. 5C). This analysis did reveal a small cluster of genes (red cluster) that were repressed by E2, and for which 4OHT was able to raise the expression level above the basal level Fig. 5A. It should be noted, however, that the absolute magnitude of change in the expression of these genes is small, and we believe is related to an ER-independent activity of 4OHT. ASCL1 is an example of a gene whose expression is subject to inverse agonist regulation by all SERM except 4OHT; its regulation pattern is illustrated in Fig. 5D.

Fig. 5.

Analysis of expression of 329 probe sets reporting on genes on which inverse agonist activity of at least one SERM was observed. A, Clustering diagram. B and C, Bivariate plots showing the extent of regulation, expressed as the log2-transformed ratio of intensities, for SERM-E2 vs. E2 and SERM vs. vehicle comparisons, respectively. Dashed lines indicate the log-ratio of zero (no change). Smoother lines (running mean) are included on the bivariate plots. D, Expression profile of a representative gene from this class, ASCL1, obtained in an independent experiment, as determined by qPCR. For additional data, see Supplemental Fig. 3.

3) Partial agonist/antagonist activity

In this study, we were surprised to find relatively few genes, upon which SERM functioned as partial agonists, mimicking E2 at some level when tested alone and able to partially inhibit E2 activation (Fig. 6). Indeed, we only identified 38 probe sets, reporting on 27 unique transcripts, upon which at least one SERM exhibited partial agonist activity. The relationship among SERM activities on these genes is shown in Fig. 6. The majority of genes were included in this group as a consequence of their ability to support the partial agonist activity of 4OHT. Nine probe sets, reporting on six genes, for which 4OHT acts as a full agonist, were selected due to partial agonist activity of Ral. It should be noted that we did identify a significant number of genes whose E2 induced activity was significantly repressed by at least one SERM, but on which SERM were not shown to exhibit significant partial agonist activity. The mechanism(s) underlying this interesting pharmacological activity are currently been evaluated. The representative gene from this class is RAPGEFL1, whose expression pattern is illustrated in Fig. 6E.

Fig. 6.

Analysis of expression of 38 probe sets reporting on genes for which at least one SERM displays partial agonist activity. A, Clustering diagram. B–D, Bivariate plots showing the extent of regulation, expressed as the log2-transformed ratio of intensities, for SERM-E2 vs. E2, SERM-E2 vs. vehicle, and SERM vs. vehicle comparisons, respectively. Dashed lines indicate the log-ratio of zero (no change). Smoother lines (running mean) are included on the bivariate plots. E, Expression profile of a representative gene from this class, RAPGEFL1, obtained in an independent experiment, as determined by qPCR. For additional data, see Supplemental Fig. 4.

4) Additive effects of 4OHT and estradiol

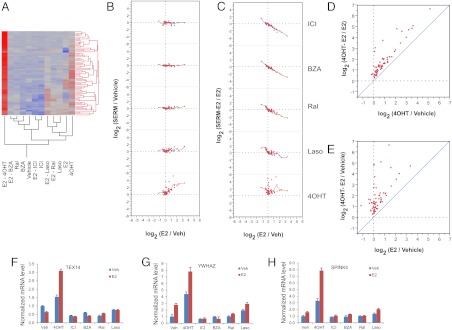

Thus far, we have described the characterization of ER-target genes on which SERM exhibit antagonist, inverse agonist, and partial agonist activities. However, in doing this large head-to-head study, we have been able to define new and unexpected pharmacological activities of this class of compounds. Of particular interest in this regard is the identification of genes on which the combined effect of E2 and 4OHT is greater than that of either ligand alone. On these genes, the treatment with the combination of 4OHT and E2 results in significantly higher expression level compared with treatment with E2 or 4OHT alone. In this manner 67 probe sets, which report on 53 unique transcripts, were identified (Fig. 7). These genes are generally insensitive to any other SERM at the basal level (Fig. 7, B and C), whereas the combination of estradiol and 4OHT significantly induced their expression above the levels achieved by E2 or 4OHT when added alone (Fig. 7, D and E). Examples of genes that exhibit this mode of regulation are TEX14, YWHAZ, and SPINK4 (Fig. 7, F–H). The significance of this particular finding will be discussed below.

Fig. 7.

Analysis of expression of 67 probe sets reporting on genes subject to additive regulation by 4OHT and E2. A, Clustering diagram. B and C, Bivariate plots showing the extent of regulation, expressed as the log2-transformed ratio of intensities, for SERM vs. vehicle and SERM-E2 vs. E2 comparisons, respectively. Dashed lines indicate the log-ratio of zero (no change). D and E, Bivariate plots showing the increase in expression level by cotreatment with E2 and 4OHT relative to 4OHT alone (D) and E2 alone (E). Smoother lines (running mean) are included on the bivariate plots. F–H, Expression profile of a representative gene from this class obtained in an independent experiment, as determined by qPCR.

5) E2-independent activities of SERM

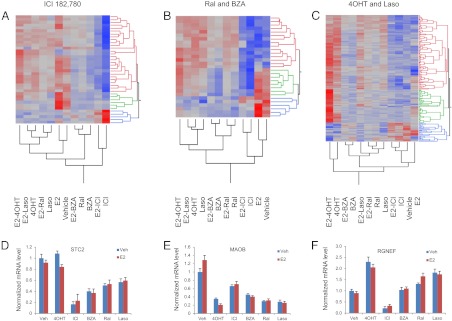

Given that SERM differentially impact ER structure and thus engender differential coregulator interactions, it was considered likely that genes would be identified whose expression was regulated by SERM(s) but not by E2. Because activities of SERM on E2-insensitive promoters result in generally very weak responses, we have additionally filtered this set of genes to ensure at least 1.5-fold change elicited by at least one SERM either by itself or in combination with E2. Patterns of responses of these genes to various ligands are illustrated on Fig. 8. Not surprisingly, given the pharmacological complexity of SERM, the expression patterns are too complex to be presented in one panel. Thus, we have broken the data down based on similarities and differences among ligands to highlight how genes identified as being responsive to 1) ICI, 2) BZA/Ral, and 3) Laso/4OHT responded to treatment with every other SERM. It is important to note that the same genes may be represented in more than one group. In Fig. 8A are represented those genes that are regulated by ICI, but which are nominally insensitive to E2. During the course of this analysis, a small group of genes was also identified whose expression was up-regulated by treatment with ICI. These genes include ACHE, LRP2, CXCR4, and c20orf175. Given its role in the cellular uptake of small lipophilic molecules, the observation that ICI up-regulated the expression of LRP2 (megalin) was particularly interesting and suggested that this was a response to the exposure of the cells to a molecule with a steroid backbone rather than an ER-dependent activity. Highlighted in Fig. 8B are those E2-insensitive genes that are regulated by both BZA and Ral. Interestingly, many of these genes are insensitive also to ICI but are regulated to some degree by 4OHT and Laso. Finally, represented in Fig. 8C are a large number of genes (169 probe sets reporting on 141 transcripts), upon which both 4OHT and Laso exhibited regulatory activity. For these genes, we observe three general patterns: 1) genes that are robustly repressed by 4OHT, less repressed by Ral, BZA, and Laso, and unaffected by ICI (Fig. 8C, blue cluster); 2) genes that are positively regulated by 4OHT and even more so by the combination of 4OHT and E2; in this respect they are similar to the genes on which “additive effects” of 4OHT and E2 were demonstrated above, except that the extent of the cumulative effect does not reach statistical significance (Fig. 8C, green cluster); and 3) a group of genes that are positively regulated by 4OHT, less so by Ral and Laso, and unaffected by E2 (Fig. 8C, red cluster). Clearly, it is this latter analysis that highlights the most significant differences among the SERM and that which likely underlies their different functional activities in target organs. Representative transcription profiles of genes in these classes are shown in Fig. 8, D–F, below the corresponding heatmap.

Fig. 8.

Analysis of expression of genes subject to E2-independent regulation by SERM. A–C, Hierarchical clustering diagrams for genes subject to baseline regulation by ICI, Ral/BZA, and 4OHT/Laso, respectively. D–F, Expression profiles of representative genes included in A–C, respectively. For additional data, see Supplemental Fig. 5.

Discussion

The diversity in the structures of ER ligands and in the resultant differences in pharmacological responses has not only provided useful therapeutics for the treatment of a variety of estrogenopathies but has also provided useful chemical probes to dissect the ER-signal transduction pathway. Coming from the latter studies is the observation that receptor conformation is the primary determinant of the pharmacological action of an ER ligand and that differently conformed ER-ligand complexes can engage functionally distinct coregulators in a differential manner (30). Although the relationship between ER structure, coregulator recruitment, and biological activity has been established (13, 31, 32), it remains to determined how, within a single cell, the same ER-ligand complex can manifest different activities on different target genes. Understanding the later aspect of ER pharmacology was the primary objective of the current study.

Several very informative studies have been published that detail the evaluation of ER transcriptome in estradiol or tamoxifen-treated MCF-7 cells (33–37). In the current study, we examined gene expression in response to structurally diverse ER ligands as a means to identify genes and gene sets that highlighted 1) similarities and differences among SERM and 2) differences in the mechanism by which ER was engaged in transcription. To this end, global changes in ER-dependent gene expression in MCF-7 cells were assessed in response to treatment with a number of clinically important ER ligands. This chemical biology approach yielded a rich data set, the analysis of which has been informative with respect to the mechanisms underlying the pharmacological actions of SERM and ER action in general. One of the most dramatic findings of this study was that over 7000 genes were shown to be regulated in a significant manner by at least one SERM. Equally surprising was the diversity in the gene expression patterns observed and the dramatic effects that subtle changes in ligand structure had on target gene transcription. These findings reinforce what is known about the relationship between the structure of the ER-ligand complex and activity highlight the difficulty in predicting the biological activity of even closely related SERM.

From the data set generated, we were able to define five broad classes of genes that are distinguishable by their response to estradiol, SERM, and SERD. Not surprisingly, the largest subset identified is comprised of genes on which estradiol functions as an agonist and on which all SERM and SERD function as classical competitive antagonists. The unifying feature of all of the SERM and the SERD that we have profiled in this study is that they competitively inhibit the binding of agonists and disrupt the integrity of the activation function (AF)-2 coactivator binding pocket. By inference, therefore, it appears that on genes on which ER-AF-2 and its associated coregulators are required, the second activation domain, AF-1, is either nonfunctional or the activities of its associated coregulators are not important on these specific target genes. General characterization of the agonist-antagonist relationship between ICI, Ral, and 4OHT reported in this manuscript is consistent with the previously reported data (38). However, by taking advantage of an expanded experimental setup, with significantly larger number of replicates and greater number of interrogated genes, as well as using additional SERM and TSEC complexes, we were able to define more subtle manifestations of SERM action, such as inverse agonist, additive, and E2-independent activities discussed below.

A subset of genes was identified on which the ER ligands ICI, BZA, and to a lesser extent Ral were found to exhibit inverse agonist activity. It was notable that on most genes in this class, ICI exhibits greater inverse agonist activity than BZA, a results that reflects differences in their SERD efficacy. As yet, we have not examined whether the receptor bound at the enhancers of these genes is turned over to the same degree as the bulk receptor in the cells. If so, then inverse agonist activity is likely to reflect the removal of the receptor from the target genes, an activity that removes a conduit for the actions of endogenous molecules with agonist activity or for signaling pathways that impinge on the ER-ligand complex. Alternatively, if the stability of the enhancer bound ER is not impacted by ICI/BZA, then their inverse agonist activity may reflect their ability to recruit inhibitory coregulators, i.e. NCoR. Indeed, the latter hypothesis is supported by the results of previous studies, in which it was shown that by overexpressing ER, the SERD activity of ICI can be saturated, yet it still possess the ability to function as an inverse agonist (39). Regardless, it will be interesting to define the structural elements at or around the enhancers of genes of this class and determine those features that track with or contribute to inverse activity.

Given what is known about SERM action, it was expected that genes would be identified, on which one or more of these drugs exhibited partial agonist activity. What was surprising, however, was that the number of genes on which partial agonist activity is manifest was relatively modest. Furthermore, most of the genes were included in this class because of their ability to support tamoxifen and to a lesser extent Laso and Ral partial agonist activity. Defining the mechanisms underlying this gene-specific partial agonist activity is likely to have a significant impact on our understanding of the mechanism of action of tamoxifen in ER-positive breast cancers and on the development of tamoxifen resistance, the process by which cells switch from recognizing this compound as an antagonist to that of an agonist. It has been known for some time that the partial agonist activity of SERM tracks with the activity of the AF-1 coregulator interacting domain in the amino terminus of ER (40, 41). What is not clear, however, is why, if AF-1 remains active in the context of some SERM-ER complexes, it does not result in agonist activity on all the promoters with which it interacts. One idea that we favor is that, on those genes on which ER-tamoxifen exhibits agonist activity, another promoter/enhancer-bound transcription factor provides the activity that would normally be provided by ER-AF-2. In this cooperativity model, the relative agonist/antagonist activity of different ER-SERM complexes would therefore reflect the impact of receptor conformation on the interaction of ER with other transcription factors associated with the promoter/enhancer. It is important to note that this model is an extension of the “coregulator” hypothesis that generally describes the relationship between nuclear receptor structure, coregulator binding, and biological activity (14, 42). However, it adds the dimension of specificity, because it explains how the activity of a SERM-ER-coregulator complex is modulated by the enhancer/promoter environment in which it operates.

Antagonism, inverse agonism, and partial agonist are three pharmacological attributed that are generally associated with SERM action. However, in this study, we also identified two new activities that are likely to have important biological implications. Specifically, a class of genes was identified whose expression was positively or negatively regulated by at least one SERM or a SERD, but on which estradiol alone had no significant impact. The physiological relevance of these types of responses is not immediately apparent. It is possible that this is purely an ectopic activity and that on some genes, the specific conformation of ER in the presence of a SERM but not estradiol is able to engage a required cofactor. Indeed, we have shown in the past that the surfaces on ER required for ER agonist and tamoxifen agonist activity are not identical (43, 44). Regardless, it is difficult to understand how the ER-estradiol complex would be inactive on some but not all target genes. It is possible that on such genes, the DNA sequence of the estrogen response element influences the overall activity of the receptor in such a way as to specifically disengage the interaction of the ER-estradiol complex with its required coregulators while having no effect on the interaction of ER-SERM complexes with the factors they need to manifest agonist activity.

The final class of genes that we identified in this study is comprised of those genes on which we observed synergistic effects of E2 and 4OHT. Intuitively, because both the SERM and estradiol compete for the same binding pocket, it is difficult to explain the activity of this class of compound. One possibility is that when both compounds are added together, heterodimeric complexes form with activities that are distinct from homodimeric agonist or SERM complexes. There is no formal proof that such heterodimeric complexes exist, although several investigators are trying to address this issue using crystallographic approaches. However, another possibility is that the addition of one compound alters the environment of the cell in such a way as to facilitate the activity of the second. For instance, addition of estradiol could alter the expression and or activity of a coregulator that then enables a SERM to manifest activity. There is precedent for the latter mechanism, in that it has been demonstrated that steroid receptor coactivator (SRC)-3 expression is significantly elevated in the mammary epithelial cells of animals treated with the antiprogestin RU486, whereas SRC-1 was observed to increase in the uterine epithelial cells of the same animals (45). This likely results from the disruption of a negative feedback loop that controls the expression of this coregulator. Although not tested, it was inferred from these studies that the increased expression of SRC-3 impacts the cellular response to progesterone receptor/agonist complexes and that of other receptors that can use this coregulator. Regardless, these findings are instructive with respect to the mechanism of action of the TSEC class of coregulators and may explain why the pharmacological actions of tamoxifen are different in pre- and postmenopausal women.

In excess of 300 functionally distinct coregulators have been identified whose ability to interact with nuclear receptors can be modulated by ligand-induced changes in receptor conformation. Given this observation, it is relatively easy to understand how differential expression of functionally distinct coregulators could explain how the relative agonist/antagonist activity of different SERM would differ between cells. However, in this study, we demonstrate that even within the same cell, a given ER-ligand complex can manifest different pharmacological activities. This highlights the importance of promoter/enhancer architecture, both the sequence of the DNA-binding elements and the functionality of factors that bind at sites juxtaposed to the receptor, in determining the response to various ligands. Several groups are involved in defining the ER-cistrome in cells as a function of SERM exposure. The results of their studies combined with the transcriptomic analysis that we have performed should allow the identification of the common structural features in genes (and allow the identification of associated factors) that display particular responses to ER ligands. Studies such as these, combined with an understanding of the roles of different coregulators in determining ER pharmacology, will be instructive with respect to the design of mechanism-based screens that can used to identify the next generation of SERM. It is anticipated that, because we define the roles of individual coregulators and specific target genes in various biological processes, these discovery efforts can be directed toward the development of compounds that exhibit process or pathway-selective activities.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant DK048807 and by Pfizer Pharmaceuticals.

Disclosure Summary: D.P.M. has served as a paid consultant for Pfizer. S.E.W. and D.K. have nothing to disclose.

NURSA Molecule Pages†:

Nuclear Receptors: ER-α;

Ligands: 17β-estradiol | 4-Hydroxytamoxifen | Fulvestrant.

Annotations provided by Nuclear Receptor Signaling Atlas (NURSA) Bioinformatics Resource. Molecule Pages can be accessed on the NURSA website at www.nursa.org.

- AF

- Activation function

- BZA

- bazedoxifene acetate

- E2

- 17β estradiol

- ER

- estrogen receptor

- ICI

- ICI 182,780

- Laso

- lasofoxifene

- 4OHT

- 4-hydroxytamoxifen

- PC

- principal component

- Ral

- raloxifene

- RT-qPCR

- real-time quantitative PCR

- SERD

- selective ER degrader

- SERM

- selective ER modulator

- SRC

- steroid receptor coactivator

- TSEC

- tissue-selective estrogen complex.

References

- 1. Devin-Leclerc J, Meng X, Delahaye F, Leclerc P, Baulieu EE, Catelli MG. 1998. Interaction and dissociation by ligands of estrogen receptor and Hsp90: the antiestrogen RU 58668 induces a protein synthesis-dependent clustering of the receptor in the cytoplasm. Mol Endocrinol 12:842–854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Walf AA, Paris JJ, Rhodes ME, Simpkins JW, Frye CA. 2011. Divergent mechanisms for trophic actions of estrogens in the brain and peripheral tissues. Brain Res 1379:119–136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kolovou G, Giannakopoulou V, Vasiliadis Y, Bilianou H. 2011. Effects of estrogens on atherogenesis. Curr Vasc Pharmacol 9:244–257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Smith EP, Specker B, Korach KS. 2010. Recent experimental and clinical findings in the skeleton associated with loss of estrogen hormone or estrogen receptor activity. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 118:264–272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Vogel VG, Costantino JP, Wickerham DL, Cronin WM, Cecchini RS, Atkins JN, Bevers TB, Fehrenbacher L, Pajon ER, Jr, Wade JL, 3rd, Robidoux A, Margolese RG, James J, Lippman SM, Runowicz CD, Ganz PA, Reis SE, McCaskill-Stevens W, Ford LG, Jordan VC, Wolmark N. 2006. Effects of tamoxifen vs raloxifene on the risk of developing invasive breast cancer and other disease outcomes. JAMA 295:2727–2741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cummings SR, Eckert S, Krueger KA, Grady D, Powles TJ, Cauley JA, Norton L, Nickelsen T, Bjarnason NH, Morrow M, Lippman ME, Black D, Glusman JE, Costa A, Jordan VC. 1999. The effect of raloxifene on risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women: results from the MORE randomized trial. JAMA 281:2189–2197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Love RR, Mazess RB, Barden HS, Epstein S, Newcomb PA, Jordan VC, Carbone PP, DeMets DL. 1992. Effects of tamoxifen on bone mineral density in postmenopausal women with breast cancer. New Engl J Med 326:852–856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Love RR, Wiebe DA, Newcomb PA, Cameron L, Leventhal H, Jordan VC, Feyzi J, DeMets DL. 1991. Effects of tamoxifen on cardiovascular risk factors in postmenopausal women. Ann Int Med 115:860–864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. McDonnell DP, Clemm DL, Hermann T, Goldman ME, Pike JW. 1995. Analysis of estrogen receptor function in vitro reveals three distinct classes of antiestrogens. Mol Endocrinol 9:659–669 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Walsh BW, Kuller LH, Wild RA, Paul S, Farmer M, Lawrence JB, Shah AS, Anderson PW. 1998. Effects of raloxifene on serum lipids and coagulation factors in healthy postmenopausal women. JAMA 279:1445–1451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Delmas PD, Bjarnason NH, Mitlak BH, Ravoux AC, Shah AS, Huster WJ, Draper M, Christiansen C. 1997. Effects of raloxifene on bone mineral density, serum cholesterol concentrations, and uterine endometrium in postmenopausal women. N Engl J Med 337:1641–1647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Vogel VG. 2009. The NSABP Study of tamoxifen and raloxifene (STAR) trial. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther 9:51–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schwartz JA, Skafar DF. 1993. Ligand-mediated modulation of estrogen receptor conformation by estradiol analogs. Biochemistry 32:10109–10115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wolf IM, Heitzer MD, Grubisha M, DeFranco DB. 2008. Coactivators and nuclear receptor transactivation. J Cell Biochem 104:1580–1586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Shang Y, Brown M. 2002. Molecular determinants for the tissue specificity of SERMs. Science 295:2465–2468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Li C, Liang YY, Feng XH, Tsai SY, Tsai MJ, O'Malley BW. 2008. Essential phosphatases and a phospho-degron are critical for regulation of SRC-3/AIB1 coactivator function and turnover. Mol Cell 31:835–849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cavarretta IT, Mukopadhyay R, Lonard DM, Cowsert LM, Bennett CF, O'Malley BW, Smith CL. 2002. Reduction of coactivator expression by antisense oligodeoxynucleotides inhibits ERα transcriptional activity and MCF-7 proliferation. Mol Endocrinol 16:253–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hall JM, McDonnell DP, Korach KS. 2002. Allosteric regulation of estrogen receptor structure, function, and coactivator recruitment by different estrogen response elements. Mol Endocrinol 16:469–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hall JM, McDonnell DP. 1999. The estrogen receptor β-isoform (ERβ) of the human estrogen receptor modulates ERα transcriptional activity and is a key regulator of the cellular response to estrogens and antiestrogens. Endocrinology 140:5566–5578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Norris JD, Paige LA, Christensen DJ, Chang CY, Huacani MR, Fan D, Hamilton PT, Fowlkes DM, McDonnell DP. 1999. Peptide antagonists of the human estrogen receptor. Science 285:744–746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ke HZ, Qi H, Crawford DT, Chidsey-Frink KL, Simmons HA, Thompson DD. 2000. Lasofoxifene (CP-336,156), a selective estrogen receptor modulator, prevents bone loss induced by aging and orchidectomy in the adult rat. Endocrinology 141:1338–1344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Komm BS, Kharode YP, Bodine PV, Harris HA, Miller CP, Lyttle CR. 2005. Bazedoxifene acetate: a selective estrogen receptor modulator with improved selectivity. Endocrinology 146:3999–4008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Komm BS, Chines AA. 2012. An update on selective estrogen receptor modulators for the prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. Maturitas 71:221–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Silverman SL. 2010. New selective estrogen receptor modulators (SERMs) in development. Curr Osteoporos Rep 8:151–153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Komm BS. 2008. A new approach to menopausal therapy: the tissue selective estrogen complex. Reprod Sci 15:984–992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Stovall DW, Utian WH, Gass ML, Qu Y, Muram D, Wong M, Plouffe L., Jr 2007. The effects of combined raloxifene and oral estrogen on vasomotor symptoms and endometrial safety. Menopause 14:510–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Levine J. 2011. Treating menopausal symptoms with a tissue-selective estrogen complex. Gender Med 8:57–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(ΔΔC(T)) method. Methods 25:402–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Benito M, Parker J, Du Q, Wu J, Xiang D, Perou CM, Marron JS. 2004. Adjustment of systematic microarray data biases. Bioinformatics 20:105–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Paige LA, Christensen DJ, Grøn H, Norris JD, Gottlin EB, Padilla KM, Chang CY, Ballas LM, Hamilton PT, McDonnell DP, Fowlkes DM. 1999. Estrogen receptor (ER) modulators each induce distinct conformational changes in ERα and ERβ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 96:3999–4004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bruning JB, Parent AA, Gil G, Zhao M, Nowak J, Pace MC, Smith CL, Afonine PV, Adams PD, Katzenellenbogen JA, Nettles KW. 2010. Coupling of receptor conformation and ligand orientation determine graded activity. Nat Chem Biol 6:837–843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ashley C.W P. 2006. Lessons learnt from structural studies of the oestrogen receptor. Best Pract Res Cl En 20:1–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Inoue A, Yoshida N, Omoto Y, Oguchi S, Yamori T, Kiyama R, Hayashi S. 2002. Development of cDNA microarray for expression profiling of estrogen-responsive genes. J Mol Endocrinol 29:175–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Salazar MD, Ratnam M, Patki M, Kisovic I, Trumbly R, Iman M, Ratnam M. 2011. During hormone depletion or tamoxifen treatment of breast cancer cells the estrogen receptor apoprotein supports cell cycling through the retinoic acid receptor α1 apoprotein. Breast Cancer Res 13:R18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Wang DY, Fulthorpe R, Liss SN, Edwards EA. 2004. Identification of estrogen-responsive genes by complementary deoxyribonucleic acid microarray and characterization of a novel early estrogen-induced gene: EEIG1. Mol Endocrinol 18:402–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Frasor J, Chang EC, Komm B, Lin CY, Vega VB, Liu ET, Miller LD, Smeds J, Bergh J, Katzenellenbogen BS. 2006. Gene expression preferentially regulated by tamoxifen in breast cancer cells and correlations with clinical outcome. Cancer Res 66:7334–7340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gadal F, Starzec A, Bozic C, Pillot-Brochet C, Malinge S, Ozanne V, Vicenzi J, Buffat L, Perret G, Iris F, Crepin M. 2005. Integrative analysis of gene expression patterns predicts specific modulations of defined cell functions by estrogen and tamoxifen in MCF7 breast cancer cells. J Mol Endocrinol 34:61–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Frasor J, Stossi F, Danes JM, Komm B, Lyttle CR, Katzenellenbogen BS. 2004. Selective estrogen receptor modulators: discrimination of agonistic versus antagonistic activities by gene expression profiling in breast cancer cells. Cancer Res 64:1522–1533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wardell SE, Marks JR, McDonnell DP. 2011. The turnover of estrogen receptor α by the selective estrogen receptor degrader (SERD) fulvestrant is a saturable process that is not required for antagonist efficacy. Biochem Pharmacol 82:122–130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. McInerney EM, Katzenellenbogen BS. 1996. Different regions in activation function-1 of the human estrogen receptor required for antiestrogen- and estradiol-dependent transcription activation. J Biol Chem 271:24172–24178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Fujita T, Kobayashi Y, Wada O, Tateishi Y, Kitada L, Yamamoto Y, Takashima H, Murayama A, Yano T, Baba T, Kato S, Kawabe Y, Yanagisawa J. 2003. Full activation of estrogen receptor α activation function-1 induces proliferation of breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem 278:26704–26714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kato S, Yokoyama A, Fujiki R. 2011. Nuclear receptor coregulators merge transcriptional coregulation with epigenetic regulation. Trends Biochem Sci 36:272–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Schaufele F, Chang CY, Liu W, Baxter JD, Nordeen SK, Wan Y, Day RN, McDonnell DP. 2000. Temporally distinct and ligand-specific recruitment of nuclear receptor-interacting peptides and cofactors to subnuclear domains containing the estrogen receptor. Mol Endocrinol 14:2024–2039 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Clemm DL, Macy BL, Santiso-Mere D, McDonnell DP. 1995. Definition of the critical cellular components which distinguish between hormone and antihormone activated progesterone receptor. J Steroid Biochem Molec Biol 53:487–495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Han SJ, Tsai SY, Tsai MJ, O'Malley BW. 2007. Distinct temporal and spatial activities of RU486 on progesterone receptor function in reproductive organs of ovariectomized mice. Endocrinology 148:2471–2486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.