The extraordinary intricacy of all the factors to be taken into consideration leaves only one way of presenting them open to us. We must select first one and then another point of view, and follow it up through the material as long as the application of it seems to yield results.

Sigmund Freud (1915)

John Bowlby (1969/1982) opens the first book of his classic Attachment trilogy with this quotation from Sigmund Freud in a chapter titled “Point of View.” Bowlby then goes on to carefully outline his own paradigm-altering point of view, building from extensive observations of young children separated from their parents. Bowlby’s selection of this quotation suggests his recognition that viewing attachment from the perspective of the young child, although remarkably productive and generative, should ultimately be just one of a number of vantage points from which we view attachment phenomena. This chapter suggests one such additional point of view.

We begin with a thought experiment. What if the Adult Attachment Interview (AAI; George, Kaplan, & Main, 1996; Main, Goldwyn, & Hesse, 2002) had come first? What if we started not with the study of infants but of adolescents? And what if the AAI originated not from attachment theory and data from the Strange Situation (a measure designed to assess the quality of the infant’s attachment to his or her caregiver), but from other perspectives on human behavior? Looking afresh at the AAI and its classification system from this vantage point, we might first simply observe that we had a measure that asked adolescents and adults about childhood relationships and then coded the degree of coherence with which the resulting emotion-laden memories emerged.

Although childhood relationships are clearly the focus of the interview, the primary emphasis in coding the interviews would not be on the quality of those relationships—even people with horrific childhood relationships can be rated high in “autonomy” and “coherence”—but on how those relationships were discussed. Nor would the AAI, at least on its face, appear to be primarily assessing a “safety regulating system” as Bowlby (1969/1982) describes infant attachment. Rather, what we might notice is that some individuals in the AAI appear to shy away from discussing strong emotional experiences from childhood. Others appear to get easily lost in such discussions. And still others are able to coherently balance recountings of intensive emotional experiences with thoughtful evaluations of those experiences.

Interestingly, even without any attachment context, the AAI remains a useful and intriguing measure. We might readily conclude that it captures an adolescent’s or adult’s ability to manage strong affect in recounting emotionally charged memories. Most (although not all) of these memories are solicited around childhood experiences with attachment figures, but whether this focus is critical would not at first glance be apparent. If the infant Strange Situation were subsequently developed and linked to parental AAI classifications, we might use this as further evidence that the AAI was capturing an aspect of affect regulation that was fundamental not so much to a parent’s attachment behavior as to his or her capacity for sensitive caregiving behavior.

The point here is not that we could envision a world in which infant attachment behavior takes on a secondary role heuristically in explaining the meaning of the AAI. Rather, it is that considering attachment-related phenomena from the perspective of adolescence suggests new ways of thinking about attachment that may be enormously generative. In the remainder of this chapter, we seek not so much to reconsider the meaning of the AAI as to use this new point of view to examine the challenges that adolescent development presents for a broader attachment theory. Ultimately we would like to show that what we are proposing is far more than a thought experiment. As we move from infancy toward adulthood, attachment processes evolve and change qualitatively and fundamentally in nature. Recognizing these changes is likely to be central to continuing to advance our understanding of attachment as a life span phenomenon.

Shifts in Perspective

Given that the vast majority of our research on attachment processes in adolescence has been done with the Adult Attachment Interview (George et al., 1996) or a version slightly adapted for adolescents (Ward & Carlson, 1995), it is important to be precise about the relation of this instrument to the construct it assesses. Given the remarkable power of the AAI in predicting infant offspring Strange Situation behavior (Main, Kaplan, & Cassidy, 1985), it is tempting to equate measure and construct and conclude that the AAI provides a direct window into precisely the same attachment system observed in infancy. Yet an indicator of a construct, even one with near perfect predictive power, is not the same as the construct. From both her explicit statements to her choice of labels for AAI classifications, Mary Main has made clear that it is premature to conclude that the AAI is simply the adult version of the infant Strange Situation (Main, 1999; Main & George, 1985). Recent research in adolescence bears out this cautionary note and forces several related shifts in perspective as we move from considering infant attachment behavior to adolescent attachment states of mind regarding attachment.

Perspective Shift 1. Adolescent attachment states of mind are not a direct reflection of infant attachment experiences and working models

Our first hint that adolescent AAIs have taken us beyond the world of infant attachment behavior comes as we examine the literature on long-term continuities in attachment behavior from infancy. Rather than robust relationships, we find somewhat tenuous links. Some studies find sizable correlations between infant attachment and future adolescent AAI security (Hamilton, 2000; Waters, Merrick, Treboux, Crowell, & Albersheim, 2000). Others find no such relationship but identify experiences beyond infancy that can account for some (though far from all) of the observed discontinuity (Weinfield, Sroufe, & Egeland, 2000). These studies span long periods of time with many important intervening variables. Instability is also found within infancy and within the same assessment technique. Thus, these findings provide only the first hint that, beginning in adolescence, links of attachment states of mind to actual attachment behavior may be less direct than expected. Security in adolescent states of mind is thus clearly not a direct translation of prior infant attachment relationships. It does not directly mirror the past, but what about the present?

Perspective Shift 2. Adolescent attachment states of mind are not a direct reflection of parental attachment status or of the current parent-adolescent relationship

If the AAI is not directly capturing qualities of prior infant-parent attachment relationships, what about the current family relationships of the adolescents who participate in this interview? Shouldn’t adolescent states of mind closely and uniquely reflect either the attachment states of mind of their parents (as the Strange Situation does so remarkably well for infants) or the quality of the current adolescent-parent attachment relationship? In addressing this question, we begin first with our own disappointment. We have been collecting and coding adolescent AAIs in our lab for the past fifteen years on a variety of samples. In some of these, we have also obtained AAIs from the parents of our teenagers. Our first question was: Would we find the same degree of correspondence between teen and parent AAIs as others have found between parent AAIs and infant Strange Situation assessments? Alas, the answer has been negative. Yes, we find correspondence—but it is on the order of a .2 correlation between mother and teen security scores using Kobak’s Q-Sort (Allen et al., 2003; Kobak, 1990). Others find similarly modest correspondences using the AAI classification system (Benoit & Parker, 1994).

What about actual parent-teen relationship behavior? Here we fare somewhat better. Indeed, we find that a combination of adolescent displays of autonomy and parental displays of sensitivity observed across a variety of contexts predicts as much as 40 percent of the variance in security in adolescent attachment states of mind (Allen et al., 2003). We have interpreted this pattern of behaviors as the adolescent analogue of the infant’s exploration from a secure base. The infant explores the environment with physical distance from the parent. By adolescence, this exploration has become of cognitive and emotional distance from parents. So reviewing these data, we might conclude that the AAI really was capturing something unique to the parent-adolescent attachment relationship—until we look at peer interaction data using similar approaches. Then we find that not only is AAI security also strongly linked to adolescents’ behavior with their peers, but that if anything, links to security appear to be stronger for behavior with peers than for behavior with parents (Allen, Porter, McFarland, McElhaney, & Marsh, in press). So, yes, adolescent states of mind are linked to behaviors with parents, but clearly this behavioral link is not at all restricted to primary attachment relationships.

Perspective Shift 3. Adolescent attachment states of mind may not even be directly assessing adolescent attachment behavioral systems

Ultimately our adolescent perspective requires us to revisit our starting point: the validation data demonstrating links from parental AAI classifications to the attachment behavior in the Strange Situation of their infant offspring (for a review of these studies, see van IJzendoorn, 1995). And here too, once we begin to carefully separate measure from construct, a critical distinction emerges. When conceptualized precisely, the parental AAI–infant Strange Situation studies do not provide direct evidence that the AAI is tapping into the parent’s attachment system. Rather, what these studies show most directly is that the AAI is tapping into the parent’s caregiving system. The one thing we know with striking clarity from these studies is that the mothers, including adolescent mothers, who are found to have autonomous states of mind regarding attachment in the AAI are able to provide care to their infants such that the infants (not the parents) ultimately behave in a secure fashion. This is not to say that other inductive or theoretical arguments do not suggest a link between the AAI and the parents’ own attachment system. Rather, the point here is that the remarkable data provided by the AAI–Strange Situation studies are not in and of themselves sufficient to support the conclusion that the AAI is assessing the adolescent’s or adult’s attachment system, and in fact they point in a slightly different direction.

On theoretical grounds, we might of course expect considerable overlap between the attachment and caregiving systems, but clearly the two are not isomorphic. There is a deceptively large conceptual leap from observing the concordance of parent AAIs and infant Strange Situations to viewing the AAI as a marker of adult attachment. There is no logically a priori reason that a construct that predicts the attachment status of one’s offspring necessarily directly reflects one’s own attachment status in other relationships, particularly given the significant distinction between serving as a caregiver to one’s offspring versus being a recipient of care in having one’s needs met in other relationships. It is far more parsimonious simply to begin with the observation that Mary Main discovered a remarkably powerful way to use interviews to tap critical aspects of the caregiving system. It then becomes an open empirical question—and one highly worthy of study—to examine the extent to which the parental caregiving system is related to that parent’s attachment system and attachment relationships.

Main and others have described the AAI as capturing an aspect of the attachment behavioral system: the internal organization of thinking and feelings regarding attachment behavior (Hesse, 1999; Main, 1999). Main has noted that this is nevertheless not the same as stating that what is seen in the AAI is the attachment system, and she carefully labels the resulting classifications from the AAI as “states of mind” regarding attachment. These states of mind parallel, but are not considered identical to, corresponding classifications of infant-parent attachments from the Strange Situation. Being a highly competent caregiver is not necessarily the same as being secure regarding one’s own attachment needs. Knowing that the two systems are related (even strongly related) is not sufficient to call them identical.

But is this a difference that makes a difference? Yes, in all likelihood. For perhaps the AAI does not yield a direct translation of the kind of attachment behavior observed in infancy in specific relationships. Perhaps it captures something far more generalized. After all, classifications from the AAI have been related to a wide array of adolescent outcomes, from depression to delinquency to peer relationship quality (Adam, Sheldon-Keller, & West, 1996; Allen, Moore, Kuperminc, & Bell, 1998; Allen et al., in press; Bernier, Larose, & Whipple, 2005; Cole-Detke & Kobak, 1996; Kobak & Cole, 1994; Kobak, Sudler, & Gamble, 1991; Larose & Bernier, 2001; McElhaney, Immele, Smith, & Allen, 2006; Wallis & Steele, 2001). Perhaps the AAI is capturing an affect regulation process that is broader and more evolved than the infant’s organization of attachment behavior with a caregiver. And perhaps it is not only our assessments that have broadened with development; perhaps infant attachment behavior and the attachment system itself have ultimately evolved into something more complex and far reaching as the organism has developed into adolescence.

Manifestations of Attachment Processes in Adolescence

From Safety and Survival to Affect Regulation

If we are to understand the ways in which attachment processes are actually manifest in adolescence, we must begin by recognizing the fundamental transformation that occurs from infancy to adolescence as the attachment behavioral system potentially evolves into a broader affect regulation system. Just as a seed pod changes dramatically as it matures into a developed plant, so too is the attachment behavioral system likely to look and be quite different in adolescence than in infancy.

In infancy, the attachment behavioral system plays a fundamental role in promoting the infant’s physical survival. Survival and affect regulation are tightly linked in that the infant is likely to be most distressed (that is, most dysregulated) when experiencing conditions such as danger, hunger, or illness that are potentially linked to survival threats. As we move toward adolescence, the frequency of true survival threats diminishes greatly, but the importance of using social interactions to regulate affect remains. Except under extreme circumstances, adolescents generally do not need their attachment figures for safety regulation, but they do routinely need and use them to regulate their emotions.

In fact, much evidence suggests that this predisposition to regulate emotion through social relationships is as hardwired in adulthood as is attachment behavior in infancy and that the same wiring may be used for both. In other species, the formation of tight social bonds has been linked to reproductive fitness and survival of one’s offspring (Silk, Alberts, & Altmann, 2003). In humans, meta-analyses indicate that a lack of adult social bonds creates a greater risk of future mortality than does cigarette smoking (House, Landis, & Umberson, 1988). On a neural level, Coan and others have pointed out that the systems responsible for maintenance of attachment appear to be virtually identical to those responsible for affect regulation (Coan, Schaefer, & Davidson, 2006; Hofer, 2006). Furthermore, Coan notes that evolutionary theorists dating to Darwin have argued that because mammalian emotional responding evolved in a social context, emotional behavior is virtually inextricable from social behavior (Brewer & Caporael, 1990; Buss & Kenrick, 1998; Darwin & Ekman, 1872/1998). Thus, it appears likely that attachment behavior and affect regulation will be tightly linked over the course of the human life span.

Recognizing both the similarities and the distinctions between the precisely defined attachment behaviors of infancy and the broader affect regulation processes of adolescence has the advantage of allowing us to begin to spell out the mechanisms by which the two are connected. The attachment behavioral system, in addition to its primary survival functions, is likely to directly facilitate the infant’s developing capacity for affect regulation and broader social bonding (Cassidy, 1994). At the same time, attachment behaviors may be conceptualized as specific instances of broader, developing affect regulation strategies. Yet well beyond infancy, these strategies are likely to be influenced by prior memories of infant experiences turning to attachment figures to manage both affect and survival goals.

In sum, we believe it is possible to view attachment behavior as distinct from but also as a precursor to broader patterns of social affect regulation. Although safety and survival obviously retain their primacy across the life span, on a practical basis, by adolescence the number of situations in which proximity to an attachment figure is required to maintain safety and survival has become vanishingly small. This is not to say that the attachment system does not remain operative, only that its primary purpose in infancy no longer has the same functional import by adolescence. In contrast, what some may consider to be more of a by-product of infant attachment behavior—learning to regulate affect in and through social interactions—becomes a central task of adolescent and adult functioning.

From Attachment to Affect Regulation: Reconciling Existing Findings

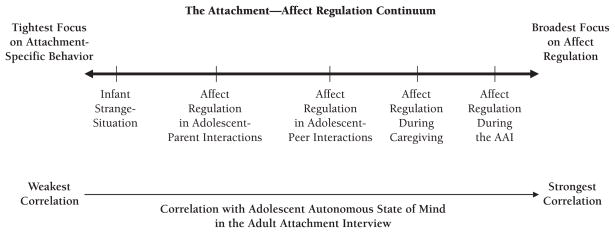

It is possible to array existing assessments on a continuum from pure attachment behaviors to assessments likely to tap broader affect regulation processes (see Figure 2.1). This continuum progresses from the infant Strange Situation, which assesses pure attachment behavior at one end, through assessments that blend elements of attachment behavior and affect regulation, to performance on the AAI, which we can now view as involving management of strong affect (albeit related to attachment memories) in the context of a discussion with an interviewer.

Figure 2.1.

The Attachment–Affect Regulation Continuum

What is striking about this continuum is that where an assessment falls along it corresponds perfectly to the magnitude of its correlation to overall classifications of security in the AAI. The infant Strange Situation has some of the weakest concordances with the adolescent AAI (although it is also furthest removed in time). Current adolescent affect regulation with parents, as assessed in both conflict and support tasks, has been more strongly linked to the AAI (Allen et al., 2003; Kobak, Cole, Ferenz-Gillies, Fleming, & Gamble, 1993). Managing affect in peer relationships—in which the task is not simply using others for support (closer to tightly defined attachment behavior) but also being responsive to the emotional needs of others (closer to a broad capacity to manage affect)—appears to have an even stronger connection to adolescent responses in the AAI (Allen et al., in press). And the strongest links to the AAI appear to be to the caregiving behaviors that lead one’s offspring to be secure in the Strange Situation—behaviors that involve little or no receipt of help managing one’s own safety needs, but rather being sufficiently capable of self-regulating one’s own affect as to be able to consistently meet the needs of another individual (to function in terms of care-giving rather than care receiving). Notably, even within this continuum, we find that assessments that lie closer to one another also tend to display the strongest connections. Thus, we have reports from the Grossmans’ lab that infant Strange Situation behavior is more strongly correlated with future autonomy negotiations with parents in adolescence, an affect-regulation paradigm with attachment figures, than with adolescent AAI security, an affect-regulation paradigm with parents absent (Zimmermann et al., 2000). Similarly, we find that affect regulation with parents is a stronger predictor of affect regulation with peers than is AAI security (Allen et al., in press).

If we want to find the strongest predictions from prior infant attachment behavior, we are likely to have the greatest success when examining areas of adolescent and adult functioning that reflect actual attachment behavior with attachment figures. From this perspective, the modest reported concordances between Strange Situation and later AAI assessments are not surprising and may not simply reflect intervening environmental events. Rather, this lack of strong concordance may in part reflect the substantial conceptual distance between an assessment of a relationship with a tight focus on attachment behavior versus an assessment of an intrapsychic characteristic that is more broadly focused on patterns of affect regulation.

None of this is to claim that the AAI is not tapping into attachment processes or that the only function of attachment beyond infancy is its contribution to affect regulation. Rather, this is to say that it is an open question as to whether what the AAI assesses is highly specific to the memories of the past attachment experiences on which it focuses or whether the underlying construct might also be almost equally well viewed in terms of broader patterns of affect regulation. We know that other AAI-like interviews tackling slightly different domains of behavior, such as the Current Relationship Interview and the Parent Development Interview (Aber, Belsky, Slade, & Crnic, 1999; Slade, Belsky, Aber, & Phelps, 1999; Slade, Slade, Grienenberger, Bernbach, Levy, & Locker, 2005; Treboux, Crowell, & Waters, 2004), are substantially but far from perfectly correlated with the AAI and demonstrate significant relations to other indicators of social-affective functioning. A critical unanswered question is the extent to which these observed patterns of adult affect regulation across different domains are relatively discrete versus overlapping.

Nor does stating that attachment in the Strange Situation and states of mind assessed in the AAI are distinct constructs mean they are unrelated. On the contrary, the organization of the attachment behavioral system undoubtedly contributes tremendously to general affect regulation capacities, as numerous researchers have now begun to document (Cassidy, 1994; Kobak et al., 1993; Kobak, Ferenz-Gillies, Everhart, & Seabrook, 1994; Mikulincer, 1998; Shaver & Mikulincer, 2002; Thompson, Flood, & Lundquist, 1995). This perspective suggests that there is likely to be tremendous value in examining the ways in which the organization of the attachment behavioral system in infancy becomes generalized beyond individual attachment relationships to affect far broader patterns of social affect regulation (Zimmermann, Maier, Winter, & Grossmann, 2001). Attachment theorists (Sroufe, Carlson, Levy, & Egeland, 1999) have rightfully been wary of claiming that attachment “explains everything” about human social behavior. And yet it is our view that a careful construction of the evolution of attachment processes will allow us to explore the ways in which attachment experiences evolve into lifelong patterns of affect regulation, within and beyond attachment relationships—that are in fact incredibly far reaching.

The Continuing Role of Relationships

Viewing the AAI as capturing one aspect of affect regulation also brings into sharp relief a major unanswered question: What about actual attachment relationships during this period? The AAI is an exquisitely sensitive instrument that has transformed the field. But to ask of an instrument that assesses an intrapsychic construct that it replace and obviate instruments that capture dyadic phenomena is to invite frustration. We next consider the ways in which an adolescent perspective suggests a need to consider both the increasing flexibility and greater complexity of adolescent relationships that serve attachment functions.

“Minor” Attachment Relationships

Infants typically have a limited number of caretakers not of their choosing. Adolescents, in contrast, can develop and select individuals to help them manage difficult emotional situations from among a wide range of candidates, including parents, teachers, relatives, close friends, romantic partners, and therapists. Furthermore, adolescents have a capacity to flexibly move into and out of such relationships. Even young adolescents appear to have the capacity to fully engage same-age peers as quasi-attachment figures for significant periods of time around certain issues. Adolescents may turn to a specific peer for comfort when distressed, feel freer exploring new behaviors in the presence of that peer, find the peer (at least for a time) irreplaceable, seek proximity with the peer, mourn the loss of the peer, and expect the peer to “be there” to meet their needs into the future (however foreshortened this future may be given an adolescent’s present-oriented perspective). These comprise all of the formal criteria that have been described for identifying attachment relationships (Ainsworth, 1989; Cassidy, 1999). Such relationships occur with sufficient frequency that they are often topics of popular literature and well described within it (see Hinton, 1967; Evans, Gideon, Sheinman, A., & Reiner, 1986), and we may be fascinated with them precisely because they represent the developing human’s first foray into recreating the power of the attachment system in new relationships with peers.

Whether we are willing to call these relationships “attachment relationships” appears in some respects as a matter of semantics. Our own inclination is to highlight the links to attachment behavior in these intensive peer interactions while continuing to draw distinctions between these interactions and primary attachment relationships. The real issue is that whatever we may call them, these relationships serve many, many attachment functions—providing felt security, affect regulation, and perhaps even actual safety—and they warrant understanding as such. The eventual development of a new primary attachment figure is of great interest and probably bears most continuity with attachment-related experiences with parents in infancy and childhood. But the capacity to adopt others as secondary, or what we might call “minor,” attachment figures—sometimes for long periods of the life span in modest ways, sometimes only for very brief periods in intense ways (for example an eighteen-year-old soldier’s comrade on a battlefield)—is also of potentially great importance. In infancy, these minor figures can be overlooked, perhaps at little cost. In adolescence and adulthood, they may become crucial. How else can we explain the healthy single mother able to raise secure offspring under often stressful circumstances, relying largely on an ensemble of what we may refer to as bit-part players in meeting her own attachment needs?

The Complexity of Attachment Relationships Beyond Childhood

Even full-fledged attachment relationships are likely to be radically different in adolescence than in infancy, for with increasing maturity, the attachment functions of relationships are going to become inextricably interwoven with other functions. In infancy, we mostly see an infant and parent both with the goal of trying to meet the infant’s needs. In adolescence and adulthood, we have two individuals, each vying to get his or her own needs met simultaneously in the same relationship. For example, a relationship in which one individual provides a consistent, reliable secure base for the attachment needs of the other—and never expects the other to reciprocate—describes a quite healthy parent-infant relationship and a quite unhealthy teen friendship.

Clearly, if we want to understand adolescent and adult attachment relationships we will need to move from the A’s, B’s, and C’s of infant classifications not simply to the D’s, E’s, and F’s of intrapsychic measures regarding attachment but to a more complex language to capture the range and variety of adolescent and adult dyadic relationships. Even the simple number of permutations of attachment states of mind grows geometrically when considering dyads as opposed to individuals. What happens, for example, when an individual with a dismissing state of mind regarding attachment becomes involved in an intense relationship with an individual with a preoccupied or secure state of mind? Intriguing research has begun to tackle these questions (Cowan & Cowan, 2001; Crowell & Treboux, 2001; Paley, Cox, Burchinal, & Payne, 1999; Treboux et al., 2004), but far more remains to be done.

Power differentials also become important. Adolescents in particular are understandably reluctant to “depend” on another figure as “older and wiser,” to use Bowlby’s term, if this means giving up a degree of power and autonomy in future conflicts. Hence, adolescents may turn less to their parents as attachment figures not simply because they need them less to self-regulate but to avoid ceding power to them. It is unarguably more difficult to challenge a parent’s authority after crying on his or her shoulder about a hard day at school. From this perspective, what might at first seem like an attachment conundrum—why an adolescent under stress might deliberately pull away from his or her primary attachment figures and refuse to communicate with them—becomes readily comprehensible. Power issues are not just superimposed on attachment behaviors; rather, they can fundamentally alter the expression of such behaviors.

These are just a few of the myriad ways in which attachment behaviors will ultimately be shaped and modified by other competing needs as the individual moves into adolescent and adult relationships. Other significant factors, such as gender, the influence of the mating system, and societal expectations of adult independence, all come to play an increasing role in how attachment behavior will be expressed. As close relationships develop beyond adolescence, security as assessed by the AAI clearly will play an important role in how these relationships develop and will influence other behavioral systems just as it is influenced by them (Furman, Simon, Shaffer, & Bouchey, 2002; Treboux et al., 2004). Indeed, at some point, the workings of the attachment behavioral system may become so tightly interwoven with that of other systems (affect regulation, reproductive, and parenting, for example) that it may make sense to reconfigure our thinking about adult behavioral systems in ways that better capture this complexity.

Future Directions

Additional research is clearly needed to advance our understanding of attachment in adolescence and beyond. Much of the discussion in this chapter, for example, presumes that the patterns of affect regulation observed in the AAI would bear at least some similarity to patterns of affect regulation in other situations that elicit strong emotion and involve intense interpersonal interaction. Research has begun to address this question by comparing AAI classifications to results of interviews targeting adolescent and adult romantic partners, although at least in adulthood, these are still potentially attachment relationships being assessed (Furman et al., 2002; Treboux et al., 2004).

Going further along these lines, efforts to assess strong affective situations that arise as a parent have also been developed, such as the Parent Development Interview (Aber et al., 1999; Slade et al., 1999), and have more potential for exploring the true generality of what is observed in the AAI to assessments in which the individual’s own attachment experiences are not the primary focus. Obviously a built-in confound will always exist in that the situations most likely to generate strong affect are typically going to be those involving human interaction, often with attachment figures. But to the extent that assessments of affect regulation patterns can be assessed using data other than memories of past attachment experiences, this is likely to advance our understanding not only of precisely what the AAI is assessing, but also of the broader links between individuals’ organization of their thinking regarding attachment and their patterns of affect regulation.

Similarly, affect regulation may occur in both contexts that are closer to attachment-relevant situations and other situations that are more distal. We might expect, for example, that affect regulation in instances in which survival is threatened (for example, around serious illnesses) might more closely resemble prior attachment behavior than strong affect around less threatening situations. If we can begin to map out ways in which patterns of affect regulation do and do not display continuity across these contexts, we will have gone a significant distance toward developing a theory that can flesh out the ways in which the attachment behavioral system contributes to, is affected by, and yet remains distinct from a broader affect regulation system.

Finally, the development of our understanding of attachment as a life span phenomenon seems most likely to be enhanced by a continued effort to move beyond the intrapsychic assessment of attachment processes to assessing actual relationship behavior. This chapter has suggested that it is possible, and indeed desirable, to tap into critical aspects of the attachment and affect regulation systems in adolescence by assessing relationships (for example, with close peers) that are not typically considered full-fledged attachment relationships. Research that begins to identify ways that patterns of relating to peers mirror and diverge from patterns of relating to parental attachment figures can help begin to flesh out the nature of the connections between these two types of relationships.

Final Thoughts

In keeping with Freud and Bowlby’s recognition of the need to continually expand our points of view, we offer in this chapter one such additional point of view regarding attachment as a life span phenomenon. We are obviously not proposing it as the correct point of view, but only as an alternative perspective on a remarkably complex phenomenon. We see nothing intrinsically wrong with the infant-centric view of attachment that has evolved as the field has grown from its infant origins. Quite to the contrary, this prior work has produced an incredibly rich and fertile ground of research and theory from which new ideas can grow and develop. Yet if we do not also examine the attachment system from completely different perspectives, we risk losing sight of the distinction between what is unique to childhood and what is unique to attachment processes across the life span.

Infancy shows us one facet of the attachment behavioral system—perhaps the most important facet—in a form that is dramatic and readily observable. But infancy is likely to provide too narrow a base on which to build an understanding of attachment across the life span. It is, of course, possible that an attachment homunculus persists inside the individual relatively unchanged throughout the life span—perhaps shifting in orientation (for example, from insecure to secure or vice versa) but retaining its fundamental form as new experiences accumulate. But it appears at least equally likely that the attachment system in infancy is more like a river that flows into the larger waters of affect regulation capacities as development progresses. We would argue that both existing data and analogies to other domains of human ontological development suggest that this second alternative merits serious consideration. Infants develop and become more complex and efficacious in their behavioral repertoires as they grow into maturity. Similarly, our theory of attachment is likely to become increasingly complex and powerful as it goes through its own process of maturation and growth in accounting for this development.

Acknowledgments

This chapter was completed with the assistance of grants from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Contributor Information

Joseph P. Allen, University of Virginia, Char-lottesville, Virginia.

Nell Manning, University of Virginia, Charlottesville.

References

- Aber JL, Belsky J, Slade A, Crnic K. Stability and change in mothers’ representations of their relationship with their toddlers. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:1038–1047. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.4.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adam KS, Sheldon-Keller AE, West M. Attachment organization and history of suicidal behavior in clinical adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:264–272. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.2.264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth MDS. Attachments beyond infancy. American Psychologist. 1989;44:709–716. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.44.4.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, McElhaney KB, Land DJ, Kuperminc GP, Moore CM, O’Beirne-Kelley H, et al. A secure base in adolescence: Markers of attachment security in the mother-adolescent relationship. Child Development. 2003;74:292–307. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.t01-1-00536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Moore C, Kuperminc G, Bell K. Attachment and adolescent psychosocial functioning. Child Development. 1998;69:1406–1419. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Porter MR, McFarland FC, McElhaney KB, Marsh PA. The relation of attachment security to adolescents’ paternal and peer relationships, depression, and externalizing behavior. Child Development. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01062.x. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benoit D, Parker KCH. Stability and transmission of attachment across three generations. Child Development. 1994;65:1444–1456. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernier A, Larose S, Whipple N. Leaving home for college: A potentially stressful event for adolescents with preoccupied attachment patterns. Attachment and Human Development. 2005;7:171–185. doi: 10.1080/14616730500147565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. Attachment and loss. Vol. 1. New York: Basic Books; 1969/1982. [Google Scholar]

- Brewer MB, Caporael LR. Selfish genes vs. selfish people: Sociobiology as origin myth. Motivation and Emotion. 1990;14:237–243. [Google Scholar]

- Buss DM, Kenrick DT. Evolutionary social psychology. Handbook of Social Psychology. 1998;2:982–1026. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy J. Emotion regulation: Influences of attachment relationships. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1994;59:228–283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy J. The nature of the child’s ties. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Coan JA, Schaefer HS, Davidson RJ. Lending a hand: Social regulation of the neural response to threat. Psychological Science. 2006;17:1032–1039. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole-Detke H, Kobak R. Attachment processes in eating disorder and depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1996;64:282–290. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.2.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan PA, Cowan CP. A couple perspective on the transmission of attachment patterns. In: Clulow C, editor. Adult attachment and couple psychotherapy: The “secure base” in practice and research. New York: Brunner-Routledge; 2001. pp. 63–82. [Google Scholar]

- Crowell J, Treboux D. Attachment security in adult partnerships. In: Clulow C, editor. Adult attachment and couple psychotherapy: The “secure base” in practice and research. New York: Brunner-Routledge; 2001. pp. 28–42. [Google Scholar]

- Darwin C, Ekman P. The expression of the emotions in man and animals. 3. New York: Oxford University Press; 1872/1998. [Google Scholar]

- Evans BA, Gideon R, Sheinman A, Producers, Reiner R., Director . Stand by me [Motion picture] United States: Columbia Pictures Company; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Freud S. Repression: The complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud. London: Hogarth Press; 1915. [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Simon VA, Shaffer L, Bouchey HA. Adolescents’ working models and styles for relationships with parents, friends, and romantic partners. Child Development. 2002;73:241–255. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George C, Kaplan N, Main M. Unpublished manuscript. 3. Department of Psychology, University of California; Berkeley: 1996. Adult Attachment Interview. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton CE. Continuity and discontinuity of attachment from infancy through adolescence. Child Development. 2000;71:690–694. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hesse E. The Adult Attachment Interview: Historical and current perspectives. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. pp. 395–433. [Google Scholar]

- Hinton SE. The outsiders. New York: Viking Press; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Hofer M. Psychobiological roots of early attachment. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2006;15:84–88. [Google Scholar]

- House JS, Landis KR, Umberson D. Social relationships and health. Science. 1988;241:540–545. doi: 10.1126/science.3399889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobak RR. Unpublished manual. University of Delaware; Newark: 1990. A Q-Sort system for coding the Adult Attachment Interview. [Google Scholar]

- Kobak RR, Cole H. Attachment and meta-monitoring: Implications for adolescent autonomy and psychopathology. In: Cicchetti D, Toth SL, editors. Disorders and dysfunctions of the self: Rochester Symposium on Developmental Psychopathology. Vol. 5. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press; 1994. pp. 267–297. [Google Scholar]

- Kobak RR, Cole H, Ferenz-Gillies R, Fleming W, Gamble W. Attachment and emotion regulation during mother-teen problem-solving: A control theory analysis. Child Development. 1993;64:231–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobak RR, Ferenz-Gillies R, Everhart E, Seabrook L. Maternal attachment strategies and emotion regulation with adolescent offspring. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 1994;4:553–566. [Google Scholar]

- Kobak RR, Sudler N, Gamble W. Attachment and depressive symptoms during adolescence: A developmental pathways analysis. Development and Psychopathology. 1991;3:461–474. [Google Scholar]

- Larose S, Bernier A. Social support processes: Mediators of attachment state of mind and adjustment in late adolescence. Attachment and Human Development. 2001;3:96–120. doi: 10.1080/14616730010024762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Main M. Attachment theory: Eighteen points. In: Cassidy J, Shaver PR, editors. Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications. New York: Guilford Press; 1999. pp. 845–887. [Google Scholar]

- Main M, George C. Responses of abused and disadvantaged toddlers to distress in agemates: A study in the day care setting. Developmental Psychology. 1985;21:407–412. [Google Scholar]

- Main M, Goldwyn R, Hesse E. Unpublished manuscript. University of California; Berkeley: 2002. Adult Attachment scoring and classification systems, Version 7.1. [Google Scholar]

- Main M, Kaplan N, Cassidy J. Security in infancy, childhood, and adulthood: A move to the level of representation. In: Bretherton I, Waters E, editors. Growing points in attachment theory and research. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1–2. Vol. 50. 1985. pp. 66–106. Serial No. 209. [Google Scholar]

- McElhaney KB, Immele A, Smith FD, Allen JP. Attachment organization as a moderator of the link between peer relationships and adolescent delinquency. Attachment and Human Development. 2006;8:33–46. doi: 10.1080/14616730600585250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikulincer M. Adult attachment style and individual differences in functional versus dysfunctional experiences of anger. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:513–524. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.2.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paley B, Cox MJ, Burchinal MR, Payne CC. Attachment and marital functioning: Comparison of spouses with continuous-secure, earned-secure, dismissing, and preoccupied attachment stances. Journal of Family Psychology. 1999;13:580–597. [Google Scholar]

- Shaver PR, Mikulincer M. Attachment-related psychodynamics. Attachment and Human Development. 2002;4:133–161. doi: 10.1080/14616730210154171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silk JB, Alberts SC, Altmann J. Social bonds of female baboons enhance infant survival. Science. 2003;302:1231–1234. doi: 10.1126/science.1088580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade A, Belsky J, Aber JL, Phelps JL. Mothers’ representations of their relationships with their toddlers: Links to adult attachment and observed mothering. Developmental Psychology. 1999;35:611–619. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.35.3.611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slade A, Slade A, Grienenberger J, Bernbach E, Levy D, Locker A. Maternal reflective functioning, attachment, and the transmission gap: A preliminary study. Attachment and Human Development. 2005;7:283–298. doi: 10.1080/14616730500245880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA, Carlson EA, Levy AK, Egeland B. Implications of attachment theory for developmental psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology. 1999;11:1–13. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499001923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson RA, Flood MF, Lundquist L. Emotional regulation: Its relations to attachment and developmental psychopathology. In: Dante C, Sheree E, Toth L, editors. Emotion, cognition, and representation. Rochester symposium on developmental psychopathology. Vol. 6. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press; 1995. pp. 261–299. [Google Scholar]

- Treboux D, Crowell JA, Waters E. When “new” meets “old”: Configurations of adult attachment representations and their implications for marital functioning. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40:295–314. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.2.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van IJzendoorn MH. Adult attachment representations, parental responsiveness, and infant attachment: A meta-analysis on the predictive validity of the Adult Attachment Interview. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117:387–403. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallis P, Steele H. Attachment representations in adolescence: Further evidence from psychiatric residential settings. Attachment and Human Development. 2001;3:259–268. doi: 10.1080/14616730110096870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward MJ, Carlson EA. Associations among adult attachment representations, maternal sensitivity, and infant-mother attachment in a sample of adolescent mothers. Child Development. 1995;66:69–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00856.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters E, Merrick S, Treboux D, Crowell J, Albersheim L. Attachment security in infancy and early adulthood: A twenty-year longitudinal study. Child Development. 2000;71:684–689. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinfield NS, Sroufe LA, Egeland B. Attachment from infancy to early adulthood in a high-risk sample: Continuity, discontinuity, and their correlates. Child Development. 2000;71:695–702. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann P, Becker-Stoll F, Grossmann K, Grossmann KE, Scheuerer-Englisch H, Wartner U. Longitudinal attachment development from infancy through adolescence. Psychologie in Erziehung und Unterricht. 2000;47:99–117. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann P, Maier MA, Winter M, Grossmann KE. Attachment and adolescents’ emotion regulation during a joint problem-solving task with a friend. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 2001;25:331–343. [Google Scholar]