Abstract

Adducin is an α, β heterotetramer that performs multiple important functions in the human erythrocyte membrane. First, adducin forms a bridge that connects the spectrin–actin junctional complex to band 3, the major membrane-spanning protein in the bilayer. Rupture of this bridge leads to membrane instability and spontaneous fragmentation. Second, adducin caps the fast growing (barbed) end of actin filaments, preventing the tetradecameric protofilaments from elongating into macroscopic F-actin microfilaments. Third, adducin stabilizes the association between actin and spectrin, assuring that the junctional complex remains intact during the mechanical distortions experienced by the circulating cell. And finally, adducin responds to stimuli that may be important in regulating the global properties of the cell, possibly including cation transport, cell morphology and membrane deformability. The text below summarizes the structural properties of adducin, its multiple functions in erythrocytes, and the consequences of engineered deletions of each of adducin subunits in transgenic mice.

Keywords: Erythrocyte adducin, Erythrocyte membrane, β-adducin, α-adducin, γ-adducin, Adducin’s function, Adducin’s regulation

1. Introduction

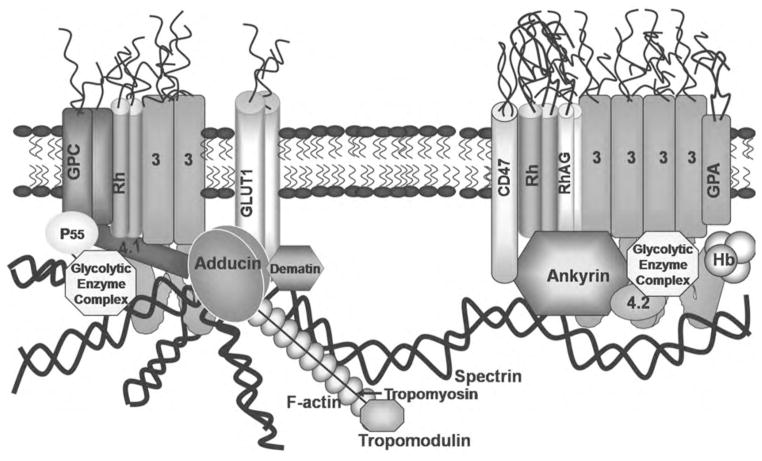

The erythrocyte membrane has served for many years as a simplified model of more complex mammalian plasma membranes (Fig. 1). The erythrocyte’s lipid bilayer is linked to an underlying membrane skeleton via integral membrane proteins, which together with the skeletal proteins help establish the shape and mechanical properties of the cell. The principal components of the membrane-associated cytoskeleton are spectrin and actin. Four to six spectrin molecules extend radially from each central actin protofilament at a supramolecular complex called the “junctional complex”. These junctional complexes are further elaborated by additional proteins, including tropomodulin, tropomyosin, protein 4.1, protein 4.2, and adducin, which individually or collectively play essential roles in forming bridges between the cytoskeleton and the lipid bilayer, enhancing spectrin-actin affinity or regulating protein interactions in the complex [1–4]. Tropomodulin, tropomyosin and adducin have also been identified as mediators of actin protofilament organization [3,5,6]. Thus, tropomodulin is involved in regulation of actin pointed end dynamics and tropomyosin has been shown to enhance red cell membrane stability by controlling the length of actin filaments [7,8].

Fig. 1.

Structural organization of the human erythrocyte membrane. This model of the erythrocyte membrane shows two major membrane protein complexes that serve to anchor the spectrin-actin cytoskeleton to the phospholipid bilayer: (1) an ankyrin-bridged complex that contains membrane-spanning proteins band 3, glycophorin A, Rh complex proteins, and CD47, in addition to the peripheral proteins ankyrin, protein 4.2, and a variety of glycolytic enzymes, [60] and (2) a junctional complex that contains the membrane-spanning proteins band 3, glycophorin C, Rh complex proteins, and a glucose transporter, in addition to peripheral proteins actin, tropomyosin, tropomodulin, adducin, dematin, p55, protein 4.1, protein 4.2, and a variety of glycolytic enzymes [60,73].

Adducin was first identified as a membrane-associated protein with calmodulin binding activity [9]. Changes in intracellular calcium had long been known to alter red cell morphology [10,11], and because calmodulin was established to mediate many calcium-induced membrane changes, its binding partners in the mature erythrocyte were investigated [9,12,13]. Identification of a new heterodimeric membrane-associated protein of Mr 97 and 103 kD with 230 nM affinity for calmodulin focused initial attention on adducin’s involvement in mediating calcium effects [9]. However, subsequent research has revealed a diversity of functions performed by this important membrane protein. The purpose of this review is to summarize the structural and functional roles played by adducin in determining and regulating the morphology and stability of the red cell. A more general review of adducin properties in multiple cell types of the body was published 10 years ago [14].

2. Adducin structure

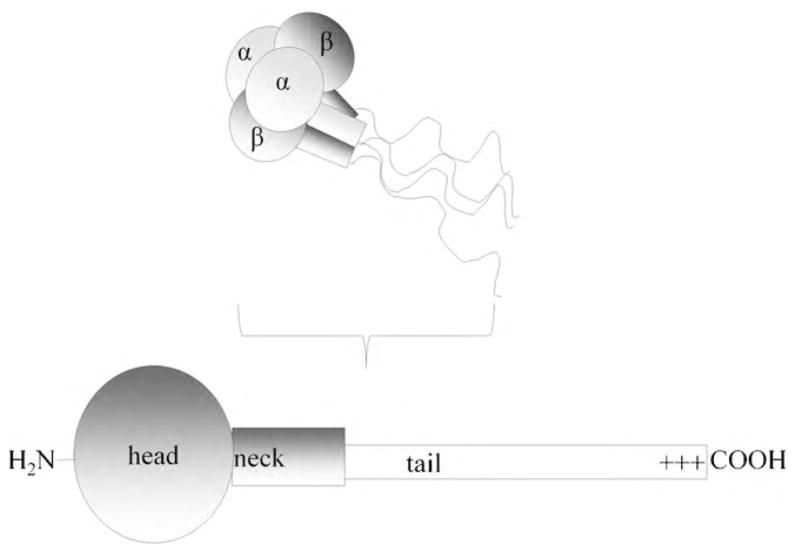

The adducin heterodimer and heterotetramer (Fig. 2) are present at ~30,000 copies/cell and its subunits are encoded by three related genes: ADD1 for α-adducin (726 amino acids), ADD2 for β (713 amino acids) and ADD3 for γ (674 amino acids) [9,15,16]. The α- and γ-subunits are ubiquitously expressed, while the β-subunit is found only in the brain and hematopoietic tissues [17]. The amino acid sequences and domain structure of the three isoforms are highly conserved, with each subunit containing a globular N-terminal head domain, a neck domain and a C-terminal tail domain. The function of the head domain has not been determined. However, some observations suggest it may participate in promoting dimerization of adducin subunits [18,19]. The neck domain is clearly involved in association of adducin monomers to heterodimers, which constitute the functionally active form of the protein [18,19]. The C-terminal tail domain binds the erythrocyte anion transporter (AE1 or band 3 [20]) and contains a highly conserved 22-residue myristoylated alanine-rich C-kinase substrate (MARCKS) domain [16,21]. This cluster of basic residues has been identified as a principal participant in most of adducin’s protein-protein interactions and in many of its regulatory activities [14,18,22].

Fig. 2.

Model of the domain structure of erythrocyte adducin. The erythrocyte adducin heterotetramer is comprised of homologous α and β subunits that have 49% identical and 66% similar amino acid sequences. Each subunit is comprised of a head, neck and tail domain. The region marked as +++ in the tail domain contains the MARCKS sequence composed of 22 basic amino acids and phosphorylation sites for both PKA and PKC. It also contains the binding site for calmodulin.

3. Protein interactions of erythrocyte adducin

3.1. Spectrin-actin junction

In addition to its binding calmodulin, adducin has been shown to interact with both spectrin and actin and thereby to stabilize their association [19,23,24]. Sedimentation experiments reveal formation of a complex directly with actin in a monomer ratio of 1:7 [24]. Since each actin protofilament contains approximately 14 actin monomers, it is likely that one adducin heterodimer binds to each actin protofilament [24]. Moreover, because actin polymerization can be terminated by addition of adducin, it can be inferred that the adducin binding site exists at the fast-growing (barbed) end of the actin filament where it can impede actin polymerization [25].

Although direct binding assays also reveal a weaker interaction with spectrin, related studies demonstrate that adducin’s affinity for spectrin can be increased at least 10-fold in the presence of actin [23]. Thus, based on both direct binding measurements and thermodynamic arguments, it can be concluded that adducin promotes the recruitment of spectrin molecules to actin filaments [19,24]. Moreover, in contradistinction to protein 4.1, which has a higher affinity for spectrin and also stabilizes spectrin-actin interactions, adducin binds more avidly to actin than spectrin [19,26,27]. And consistent with data suggesting that the neck and MARCKS-related domains of adducin are required for the actin-capping, actin binding and spectrin recruitment activities, kinases and regulatory proteins that modulate this region of adducin are also thought to regulate adducin’s ability to cap actin filaments and promote spectrin assembly on these filaments [18,22,28].

3.2. Calmodulin

As noted above, adducin was first identified as a calmodulin binding protein [9]. Calmodulin associates with adducin in a calcium dependent manner with a Kd of 230 nM at residues 425–461 within the polypeptide’s COOH-terminal tail domain [29]. Importantly, calmodulin binding down-regulates adducin’s capping and spectrin recruitment activities, suggesting a possible pathway for regulation of the erythrocyte membrane in response to changes in intracellular Ca2+ concentration [22]. However, because Ca2+ affects so many processes in the red cell [30–34], it is difficult to quantitate the impact that regulation of the adducin–spectrin–actin interaction exerts on membrane properties.

3.3. Band 3

Band 3 comprises 25% of the total erythrocyte membrane protein and is the most abundant polypeptide in the membrane [35–37]. Band 3 consists of a 55 kD membrane-spanning domain which catalyzes Cl−/HCO3− exchange across the bilayer and a 43 kD cytoplasmic domain (cdb3) that functions principally as an anchor for other membrane proteins, including ankyrin, protein 4.1, protein 4.2, hemoglobin and glycolytic enzymes [38–49]. It is this latter domain of band 3 that has been shown to bind adducin and participate in the formation of both major bridges between the lipid bilayer and the spectrin-actin skeleton [20].

The first of the aforementioned bridges connecting band 3 to the cytoskeleton is established primarily by the association of the NH2-terminal domain of ankyrin with the cytoplasmic domain of band 3 [43] and the adjacent domain of ankyrin with repeats 14 and 15 of β-spectrin [50]. Disruption of the band 3-ankyrin bridge or generation of transgenic mice defective in this interaction have been shown to lead to erythrocytes with compromised stability [51–54], suggesting that the band 3-ankyrin linkage is important to membrane mechanical properties.

The second major bridge connecting band 3 to the spectrin-actin skeleton is mediated by its association with adducin at the spectrin-actin junctional complex. While early studies suggested that the glycophorin C-protein 4.1-spectrin linkage might perform this critical function, rupture of the glycophorin-protein 4.1 interaction was subsequently shown to have no impact on membrane mechanical properties [55,56], and reconstitution of protein 4.1 deficient membranes with solely the spectrin-actin binding domain of protein 4.1 was found to restore normal membrane mechanical properties without reestablishing the glycophorin C-protein 4.1 bridge [57]. These findings indicated that an alternative membrane-to-junctional complex bridge must contribute more significantly to membrane mechanical properties, and therefore, a search for this alternative interaction was undertaken. A subsequent observation that some adducin remains associated with inside-out erythrocyte membrane vesicles following removal of spectrin and actin suggested that adducin might have an independent ability to bind the erythrocyte membrane and thereby participate in anchoring the cytoskeleton. A search for the membrane anchor of adducin was therefore undertaken [20].

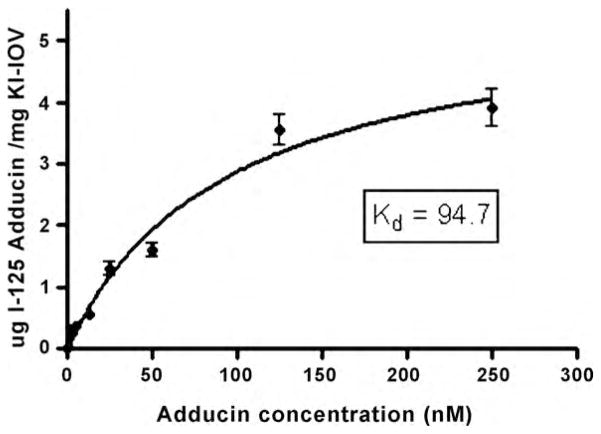

Evidence that the membrane anchor of the adducin-spectrin-actin complex was, in fact, band 3 emerged from several studies. First, label transfer experiments demonstrated that adducin associates with the cytoplasmic domain of band 3 in leaky ghosts [20]. Quantitative analyses of adducin binding to band 3 both in purified form and on the red cell membrane, then revealed that the interaction was characterized by a Kd of ~100 nM (Fig. 3). The COOH-terminal tail domains of both α-and β-adducin subunits were then identified as the sites of cdb3 binding, and competition studies revealed that fragments of adducin tail domains or antibodies to band 3 could block adducin binding to the membrane [20]. Analyses of the adducin content of band 3 in null mice demonstrated a 35% reduction in adducin levels in the cell, suggesting either that adducin’s trafficking to the membrane during erythropoiesis was compromised or its stability on the membrane was reduced by the absence of band 3. Most importantly, however, addition of adducin tail domain fragments that compete for the adducin-band 3 interaction in vitro were found to lead to spontaneous membrane fragmentation when added to lysed red cells, suggesting that the band 3-adducin bridge to the membrane skeleton is critical to membrane stability [20].

Fig. 3.

Binding of adducin to KI-stripped inside-out erythrocyte membrane vesicles.

Given the above evidence for a critical structural role for adducin in linking the junctional complex to the lipid bilayer, it was not surprising to learn that the band 3-adducin interaction might be regulated. Importantly, the interaction has been found to be sensitive to Mg2+ over the normal range of free Mg2+ concentrations in the cell [20]. Under deoxygenated conditions, when 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate is bound by deoxyhemoglobin, the free Mg2+ concentration is ~4 mM and adducin’s affinity for band 3 is high. In contrast, under oxygenated conditions, when Mg2+ is largely bound to 2,3-bisphosphoglycerate, free Mg2+ is low and adducin’s affinity for band 3 is also low. These data imply that the oxygenation state of the red cell could exert an impact on membrane mechanical properties by regulating the attachment of adducin to the membrane.

Establishment of the band 3-adducin bridge between the bilayer and the spectrin-actin junctional complex has been able to explain several previously confusing observations. First, prior identification of three populations of band 3 based on their diffusion properties and sedimentation coefficients can now be explained by an ankyrin-attached, adducin-attached, and freely diffusing population of band 3 [58,59]. Second, the observation that mutation of the ankyrin binding site on band 3 yields red cells with only partially reduced stability can now be understood by noting that up to half of the band 3 bridges to the cytoskeleton remain intact in these mutated cells [53]. This same observation can also explain why the population of cytoskeletally attached band 3 is reduced by only 60% in transgenic erythrocytes that express the mutated band 3-ankyrin interaction [53]. Third, the earlier perplexing observations that demonstrated that two binding partners of band 3 (i.e. Rh proteins and protein 4.2) are both situated in part at the junctional complex are now consistent with the localization of a fraction of band 3 at this same complex [60]. Fourth, deletion of α-spectrin has been shown to lead to a reduction in the membrane content of both adducin and band 3, suggesting that the expected decrease in adducin might also trigger a loss of band 3 [61]. Finally, the aforementioned findings that membrane mechanical properties remain unaltered after rupture of the glycophorin C-protein 4.1 bridge and that reconstitution of the spectrin-actin binding domain of protein 4.1 into 4.1/glycophorin C-deficient membranes restores membrane mechanical properties without re-establishing the glycophorin C-protein 4.1 linkage [55] are understood by recognizing that the band 3-adducin bridge, and perhaps a recently characterized dematin-glucose transporter 1 interaction, provide important stabilizing linkages to the junctional complex.

3.4. Stomatin

Stomatin is a 31 kD polypeptide that contains a highly hydrophobic stretch comprising residues 26–54 thought to somehow mediate membrane association [62,63]. Because previous studies have revealed that both the COOH- and NH2-termini of stomatin are cytoplasmic in orientation, some have inferred that a hairpin membrane insertion loop may anchor the polypeptide to the membrane [62,64]. However, this topography has not been directly demonstrated. Importantly, mutations leading to the absence of stomatin result in osmotically fragile cells with increased cation fluxes and elevated intracellular sodium concentrations [65–68]. Moreover, observations that Milan hypertensive rats, which carry a mutation in both β and α adducin genes, also display increased erythrocyte cation fluxes [69] have suggested that regulation of cation transport may depend on an interaction between adducin and stomatin.

Following up on these early observations, Sinard et al. demonstrated that stomatin interacts directly with both α- and β-adducin subunits with a Kd of ~100 nM [70]. Overlay binding experiments further localized the stomatin binding site on adducin to residues 329–726, and subsequent mutagenesis studies, then delimited the binding site to residues 533–726 of the tail domain. Although the principal function of this interaction has not been identified, the authors have speculated that association with stomatin may serve as a sensor that enables the membrane to respond to mechanical stresses by altering its permeability to cations [71].

3.5. Glucose transporter-1

The glucose transporter-1 is a transmembrane polypeptide that accounts for 10% of the total membrane protein and exists at 200,000 copies per cell [71]. Although the principal function of GLUT1 is to facilitate transport of glucose and L-dehydroascorbic acid (DHA) across the membrane, the extraordinarily high abundance of the transporter in erythrocytes implies that the protein could play additional roles in red cell biology.

In studies aimed at characterizing any auxiliary roles for GLUT1, Khan et al. demonstrated by surface labeling, immunoprecipitation and vesicle proteomic approaches a direct or indirect interaction of both dematin and adducin with GLUT1 [72]. Moreover, co-expression of adducin with GLUT1 in HEK293T epithelial cells allowed co-immunoprecipitation of the two proteins, confirming that some type of interaction between the two proteins can exist. In this same manuscript, the authors established that dematin and adducin bind independently to GLUT-1, suggesting that a macro-complex containing the three proteins could also assemble [72]. However, the specific existence of an endogenous adducin-GLUT1 complex in the mature red cell has not yet been demonstrated.

4. Erythrocye adducin regulation

The MARCKS-related sequences in the tail domains of both α- and β-adducin (i.e. the sequences primarily responsible for both actin capping and spectrin recruitment) have also been shown to constitute prominent in vivo and in vitro phosphorylation sites for both protein kinase A (PKA) and protein kinase C (PKC) [22,28]. More specifically, the major phosphorylation site for both protein kinases in α-adducin is Ser726, while the major phosphorylation site in β-adducin is Ser713 [22,28]. Other PKA phosphorylation sites on α-adducin (Ser408, Ser436 and Ser481) reside in the neck domain [22]. Importantly, PKA and PKC phosphorylation of adducin’s Marcks domain down-regulates both the actin-capping and spectrin recruitment activities by displacing adducin from the actin/spectrin network [22,73]. Because kinase-mediated dissociation of adducin from the actin protofilaments should result in exposure of their barbed (fast growing) ends, PKA and PKC have the potential to regulate membrane morphology. Finally, Rho kinase has also been shown to phosphorylate α-adducin at residues Thr445 and Thr480, resulting in enhancement of adducin’s affinity for actin [74,75].

As noted above, the Ca2+-calmodulin complex also binds at the C-terminus of adducin and inhibits its skeletal protein binding activity [23,25]. When considered together with the effects of adducin phosphorylation on its interaction with the spectrin-actin junctional complex, we hypothesize that adducin constitutes a major regulator of the architecture of this important region of the membrane.

5. Effect of targeted deletion of adducin isoforms

As noted above, adducin is encoded by three different genes (α,β, and γ); α- and γ- adducins are ubiquitously expressed, whereas β-adducin is limited to the brain and hematopoietic cells [17]. To elucidate the roles of the various adducins in vivo, each isoform has been sequentially and simultaneously knocked out in transgenic mice. The biological consequences of these gene knockouts will be described below.

5.1. Targeted deletion of β-adducin

β-adducin was the first of the adducin subunits to be knocked out in erythrocytes [17]. Not surprisingly, α-adducin, its partner in the adducin oligomer, was also reduced by 70%. However, γ-adducin was simultaneously increased approximately fivefold compared to its wild-type level, indicating that α-adducin requires a heterologous partner for its function and stability. Because this up-regulation of γ-adducin partially compensated for the loss of β-adducin, a true knockout phenotype was not achieved.

In addition to a decline in α-adducin, β-adducin knockout erythrocytes also exhibited a decrease in tropomyosin and an increase in EcapZα and EcapZβ [17]. Usually EcapZs, i.e. muscle actin-capping proteins, are present in the cytosol of red cells [76]. However, in the absent of β-adducin, both become membrane-associated, probably compensating for the loss of β-adducin’s actin capping function [77]. The other major skeleton proteins were present in normal amounts.

Hematologic studies demonstrate a severe decrease in the hematocrit of β-adducin deficient cells coupled with the anticipated increase in reticulocytes, indicating a compensatory response for the red cell hemolysis. Similar to hereditary spherocytosis, β-adducin knockout erythrocytes also reveal a loss of membrane surface area and partial red cell dehydration. The loss of membrane surface is thought to derive from the reduced number of adducin-band 3 bridges stabilizing the connections between the spectrin-actin skeleton and the lipid bilayer.

A naturally occurring deficit in β-adducin has also been associated with hypertension [69,78], as seen in Milan hypertensive rats that suffer from increased arterial blood pressure.

5.2. Targeted deletion of α-adducin

Knockout of α-adducin yields mice in which the polypeptide cannot be detected in any tissues, including erythrocytes, lungs, brain, spleen, and heart [79]. With exception of the brain and erythrocytes, no abnormalities were obvious in any other tissues. In red cells, β- and γ-adducin could not be detected, suggesting that the lack of α-adducin decreases the stability of the homologous isoform in the oligomer. Curiously, membrane skeletons from adducin null mice were found to contain normal amounts of the major proteins, including band 3, spectrin, ankyrin, protein 4.1 and glycophorin-C [79]. However, EcapZα was up-regulated by 3.5-fold, suggesting a compensation for the lack of adducin at the fast-growing ends of actin filaments. In contrast to β-adducin knockout mice, tropomodulin was not reduced and tropomyosin was diminished only 15 to 20% compared to wild-type cells, suggesting that adducin may be partially involved in retention of tropomyosin on the membrane.

Hematologic studies of α-adducin knockout mice demonstrate an increase in both mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration and hemoglobin distribution width, indicating the presence of spherocytes [79]. This was confirmed by electron microscopy and Wright-Giemsa staining, showing a population of hypochromic, microcytic, and spherocytic cells. Moreover, knockout cells exhibited an increase in osmotic fragility and decrease in maximum deformability compared to wild-type erythrocytes, further suggesting a loss of membrane surface area. Because a commonly held view argues that spherocytosis can arise whenever a disruption in vertical linkages connecting the bilayer to the spectrin-actin skeleton occurs, these data confirm the likely involvement of adducin in bridging the junctional complex to band 3. Since GLUT1 (a hypothesized auxiliary anchor to adducin) is not present in mature mouse red cells [72], the loss of the band 3-adducin bridge may be especially profound in murine erythrocytes.

5.3. Targeted deletion of γ-adducin

Although the major forms of adducin in red blood cells are the αβ heterodimer and heterotetramer [14,19], low levels of γ-adducin have also been detected in murine red cells. As previously shown, γ-adducin is up-regulated in β-adducin knockout mice, probably to compensate for the absence of the deleted protein [17]. In order to analyze in greater detail the function of γ-adducin in red cells, a null mouse was created [80]. As demonstrated by different methods, γ-adducin knockout red cells have no abnormal phenotype and the hematological parameters of the knockout mice are normal [80]. Moreover, all of the major membrane proteins, including α- and β-adducin, band 3, spectrin, ankyrin and actin are present in normal quantities.

5.4. Targeted deletion of β- and γ-adducin

Based on the up-regulation of γ-adducin in β-adducin knockout cells, it was suggested that α-adducin might be capable of forming a stable heterotetramer with γ-adducin and thereby partially restore adducin’s function on the membrane [17]. In order to investigate whether a simultaneous lack of βand γ-adducin might impart a greater instability to the cell than a β-deletion alone, β/γ-adducin double knockout mice were created [80]. These double knockout cells exhibited similar symptoms to the β-adducin knockout mice alone. However, the accompanying decrease in α-adducin content was much greater in the double knockouts (<1% of wild-type) than the β-adducin knockout. This finding supports the idea that stable hetero-oligomers are required for incorporation of adducin on the membrane.

6. Conclusions

Adducin is now known to perform several important functions in the mature erythrocyte membrane. First, it contributes to formation of a major bridge that is essential to the global morphology and stability of the membrane [20]. Second, it caps actin filaments at their barbed ends, thereby preventing their uncontrolled elongation into macroscopic F-actin filaments [25]. Third, it helps cement the critical association of spectrin with actin at the junctional complex, avoiding the membrane mechanical instabilities that ensue when these interactions are compromised (e.g. hereditary elliptocytosis) [14,19]. Not surprisingly, because of the critical nature of these disparate functions, the interactions of adducin with its binding partners on the membrane appear to be sensitively regulated by kinases, calcium/calmodulin and cytokines. More detailed studies of this fascinating multi-functional protein will undoubtedly reveal additional intriguing properties that further highlight its important role in erythrocyte membrane biology.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest disclosure

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Bennett V. Spectrin-based membrane skeleton: a multipotential adaptor between plasma membrane and cytoplasm. Physiol Rev. 1990;70(4):1029–65. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1990.70.4.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bennett V, Gilligan DM. The spectrin-based membrane skeleton and micron-scale organization of the plasma membrane. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1993;9:27–66. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.09.110193.000331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fowler VM. Regulation of actin filament length in erythrocytes and striated muscle. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1996;8(1):86–96. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(96)80052-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilligan DM, Bennett V. The junctional complex of the membrane skeleton. Semin Hematol. 1993;30(1):74–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bennett V. The spectrin-actin junction of erythrocyte membrane skeletons. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1989;988(1):107–21. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(89)90006-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takakuwa Y, Manno S. Structure of erythrocyte membrane skeleton. Nippon Rinsho. 1996;54(9):2341–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.An X, Salomao M, Guo X, Gratzer W, Mohandas N. Tropomyosin modulates erythrocyte membrane stability. Blood. 2007;109(3):1284–8. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-07-036954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weber A, Pennise CR, Babcock GG, Fowler VM. Tropomodulin caps the pointed ends of actin filaments. J Cell Biol. 1994;127(6 Pt 1):1627–35. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.6.1627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gardner K, Bennett V. A new erythrocyte membrane-associated protein with calmodulin binding activity. Identification and purification. J Biol Chem. 1986;261(3):1339–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hebbel RP, Steinberg MH, Eaton JW. Erythrocyte calcium abnormalities in sickle cell disease. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1981;51:321–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weed RI, LaCelle PL, Merrill ET. Erythrocyte metabolism and cellular deformability. Vox Sang. 1969;17(1):32–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Agre P, Gardner K, Bennett V. Association between human erythrocyte calmodulin and the cytoplasmic surface of human erythrocyte membranes. J Biol Chem. 1983;258(10):6258–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Larsen FL, Katz S, Roufogalis BD. Calmodulin regulation of Ca2+ transport in human erythrocytes. Biochem J. 1981;200(2):185–91. doi: 10.1042/bj2000185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Matsuoka Y, Li X, Bennett V. Adducin: structure, function and regulation. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2000;57(6):884–95. doi: 10.1007/PL00000731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dong L, Chapline C, Mousseau B, Fowler L, Ramsay K, Stevens JL, et al. 35H, a sequence isolated as a protein kinase C binding protein, is a novel member of the adducin family. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(43):25534–40. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.43.25534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joshi R, Gilligan DM, Otto E, McLaughlin T, Bennett V. Primary structure and domain organization of human alpha and beta adducin. J Cell Biol. 1991;115(3):665–75. doi: 10.1083/jcb.115.3.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gilligan DM, Lozovatsky L, Gwynn B, Brugnara C, Mohandas N, Peters L. Targeted disruption of the beta adducin gene (Add2) causes red blood cell spherocytosis in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96(19):10717–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.19.10717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li X, Matsuoka Y, Bennett V. Adducin preferentially recruits spectrin to the fast growing ends of actin filaments in a complex requiring the MARCKS-related domain and a newly defined oligomerization domain. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(30):19329–38. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.30.19329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hughes CA, Bennett V. Adducin: a physical model with implications for function in assembly of spectrin-actin complexes. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(32):18990–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.32.18990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anong WA, Franco T, Chu H, Weis TL, Devlin EE, Bodine DM, et al. Adducin forms a bridge between the erythrocyte membrane and its cytoskeleton and regulates membrane cohesion. Blood. 2009;114(9):1904–12. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-02-203216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joshi R, Bennett V. Mapping the domain structure of human erythrocyte adducin. J Biol Chem. 1990;265(22):13130–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsuoka Y, Hughes CA, Bennett V. Adducin regulation. Definition of the calmodulin-binding domain and sites of phosphorylation by protein kinases A and C. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(41):25157–66. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.41.25157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gardner K, Bennett V. Modulation of spectrin-actin assembly by erythrocyte adducin. Nature. 1987;328(6128):359–62. doi: 10.1038/328359a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mische SM, Mooseker MS, Morrow JS. Erythrocyte adducin: a calmodulin-regulated actin-bundling protein that stimulates spectrin-actin binding. J Cell Biol. 1987;105(6 Pt 1):2837–45. doi: 10.1083/jcb.105.6.2837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuhlman PA, Hughes CA, Bennett V, Fowler VM. A new function for adducin. calcium/calmodulin-regulated capping of the barbed ends of actin filaments. J Biol Chem. 1996;271(14):7986–91. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.14.7986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fowler V, Taylor DL. Spectrin plus band 4.1 cross-link actin. Regulation by micromolar calcium. J Cell Biol. 1980;85(2):361–76. doi: 10.1083/jcb.85.2.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tyler JM, Hargreaves WR, Branton D. Purification of two spectrin-binding proteins: biochemical and electron microscopic evidence for site-specific reassociation between spectrin and bands 2.1 and 4. 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1979;76(10):5192–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.10.5192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsuoka Y, Li X, Bennett V. Adducin is an in vivo substrate for protein kinase C: phosphorylation in the MARCKS-related domain inhibits activity in promoting spectrin-actin complexes and occurs in many cells, including dendritic spines of neurons. J Cell Biol. 1998;142(2):485–97. doi: 10.1083/jcb.142.2.485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scaramuzzino DA, Morrow JS. Calmodulin-binding domain of recombinant erythrocyte beta-adducin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90(8):3398–402. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.8.3398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lang PA, Kaiser S, Myssina S, Wieder T, Lang F, Huber SM. Role of Ca2+-activated K+ channels in human erythrocyte apoptosis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2003;285(6):C1553–60. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00186.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lisovskaya IL, Rozenberg JM, Nesterenko VM, Samokhina AA. Factors raising intracellular calcium increase red blood cell heterogeneity in density and critical osmolality. Med Sci Monit. 2004;10(3):BR67–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lang F, Huber SM, Szabo I, Gulbins E. Plasma membrane ion channels in suicidal cell death. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2007;462(2):189–94. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2006.12.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shoshan-Barmatz V, Israelson A, Brdiczka D, Sheu SS. The voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC): function in intracellular signaling, cell life and cell death. Curr Pharm Des. 2006;12(18):2249–70. doi: 10.2174/138161206777585111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wuytack F, Raeymaekers L. The Ca(2+)-transport ATPases from the plasma membrane. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 1992;24(3):285–300. doi: 10.1007/BF00768849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Low PS. Structure and function of the cytoplasmic domain of band 3: center of erythrocyte membrane-peripheral protein interactions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1986;864(2):145–67. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(86)90009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Steck TL. The band 3 protein of the human red cell membrane: a review. J Supramol Struct. 1978;8(3):311–24. doi: 10.1002/jss.400080309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu J, Steck TL. Isolation and characterization of band 3, the predominant polypeptide of the human erythrocyte membrane. J Biol Chem. 1975;250(23):9170–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jennings ML. Kinetics and mechanism of anion transport in red blood cells. Annu Rev Physiol. 1985;47:519–33. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.47.030185.002511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaul RK, Murthy SN, Reddy AG, Steck TL, Kohler H. Amino acid sequence of the N alpha-terminal 201 residues of human erythrocyte membrane band 3. J Biol Chem. 1983;258(13):7981–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Makino S, Moriyama R, Kitahara T, Koga S. Proteolytic digestion of band 3 from bovine erythrocyte membranes in membrane-bound and solubilized states. J Biochem. 1984;95(4):1019–29. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a134689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rothstein A, Knauf PA, Grinstein S, Shami Y. A model for the action of the anion exchange protein of the red blood cell. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1979;30:483–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reithmeier RA, Lieberman DM, Casey JR, Pimplikar SW, Werner PK, See H, et al. Structure and function of the band 3 Cl−/HCO3-transporter. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1989;574:75–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1989.tb25137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bennett V, Stenbuck PJ. Association between ankyrin and the cytoplasmic domain of band 3 isolated from the human erythrocyte membrane. J Biol Chem. 1980;255(13):6424–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Campanella ME, Chu H, Wandersee NJ, Peters LL, Mohandas N, Gilligan DM, et al. Characterization of glycolytic enzyme interactions with murine erythrocyte membranes in wild-type and membrane protein knockout mice. Blood. 2008;112(9):3900–6. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-146159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chu H, Low PS. Mapping of glycolytic enzyme-binding sites on human erythrocyte band 3. Biochem J. 2006;400(1):143–51. doi: 10.1042/BJ20060792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hargreaves WR, Giedd KN, Verkleij A, Branton D. Reassociation of ankyrin with band 3 in erythrocyte membranes and in lipid vesicles. J Biol Chem. 1980;255(24):11965–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hemming NJ, Anstee DJ, Mawby WJ, Reid ME, Tanner MJ. Localization of the protein 4. 1-binding site on human erythrocyte glycophorins C and D. Biochem J. 1994;299(Pt 1):191–6. doi: 10.1042/bj2990191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Korsgren C, Cohen CM. Associations of human erythrocyte band 4.2. Binding to ankyrin and to the cytoplasmic domain of band 3. J Biol Chem. 1988;263(21):10212–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pasternack GR, Anderson RA, Leto TL, Marchesi VT. Interactions between protein 4.1 and band 3. An alternative binding site for an element of the membrane skeleton. J Biol Chem. 1985;260(6):3676–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bennett V, Lambert S. The spectrin skeleton: from red cells to brain. J Clin Invest. 1991;87(5):1483–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI115157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Anong WA, Weis TL, Low PS. Rate of rupture and reattachment of the band 3-ankyrin bridge on the human erythrocyte membrane. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(31):22360–6. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513839200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chang SH, Low PS. Identification of a critical ankyrin-binding loop on the cytoplasmic domain of erythrocyte membrane band 3 by crystal structure analysis and site-directed mutagenesis. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(9):6879–84. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211137200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stefanovic M, Markham NO, Parry EM, Garrett-Beal LJ, Cline AP, Gallagher PG, et al. An 11-amino acid beta-hairpin loop in the cytoplasmic domain of band 3 is responsible for ankyrin binding in mouse erythrocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(35):13972–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706266104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Van Dort HM, Knowles DW, Chasis JA, Lee G, Mohandas N, Low PS. Analysis of integral membrane protein contributions to the deformability and stability of the human erythrocyte membrane. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(50):46968–74. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107855200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chang SH, Low PS. Regulation of the glycophorin C-protein 4. 1 membrane-to-skeleton bridge and evaluation of its contribution to erythrocyte membrane stability. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(25):22223–30. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100604200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Reid ME, Takakuwa Y, Conboy J, Tchernia G, Mohandas N. Glycophorin C content of human erythrocyte membrane is regulated by protein 4. 1. Blood. 1990;75(11):2229–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Takakuwa Y, Tchernia G, Rossi M, Benabadji M, Mohandas N. Restoration of normal membrane stability to unstable protein 4.1-deficient erythrocyte membranes by incorporation of purified protein 4. 1. J Clin Invest. 1986;78(1):80–5. doi: 10.1172/JCI112577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Che A, Morrison IE, Pan R, Cherry RJ. Restriction by ankyrin of band 3 rotational mobility in human erythrocyte membranes and reconstituted lipid vesicles. Biochemistry. 1997;36(31):9588–95. doi: 10.1021/bi971074z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Scheuring U, Kollewe K, Haase W, Schubert D. A new method for the reconstitution of the anion transport system of the human erythrocyte membrane. J Membr Biol. 1986;90(2):123–35. doi: 10.1007/BF01869930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Salomao M, Zhang X, Yang Y, Lee S, Hartwig JH, Chasis JA, et al. Protein 4. 1R-dependent multiprotein complex: new insights into the structural organization of the red blood cell membrane. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(23):8026–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803225105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Robledo RF, Lambert AJ, Birkenmeier CS, Cirlan MV, Cirlan AF, Campagna DR, et al. Analysis of novel SPH (spherocytosis) alleles in mice reveals allele-specific loss of band 3 and adducin in alpha-spectrin-deficient red cells. Blood. 2010;115(9):1804–14. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-232199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hiebl-Dirschmied CM, Adolf GR, Prohaska R. Isolation and partial characterization of the human erythrocyte band 7 integral membrane protein. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1065(2):195–202. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(91)90230-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stewart GW, Hepworth-Jones BE, Keen JN, Dash BC, Argent AC, Casimir CM. Isolation of cDNA coding for an ubiquitous membrane protein deficient in high Na+, low K+ stomatocytic erythrocytes. Blood. 1992;79(6):1593–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Salzer U, Ahorn H, Prohaska R. Identification of the phosphorylation site on human erythrocyte band 7 integral membrane protein: implications for a monotopic protein structure. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1151(2):149–52. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(93)90098-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Eber SW, Lande WM, Iarocci TA, Mentzer WC, Hohn P, Wiley JS, et al. Hereditary stomatocytosis: consistent association with an integral membrane protein deficiency. Br J Haematol. 1989;72(3):452–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1989.tb07731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lande WM, Thiemann PV, Mentzer WC., Jr Missing band 7 membrane protein in two patients with high Na, low K erythrocytes. J Clin Invest. 1982;70(6):1273–80. doi: 10.1172/JCI110726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stewart GW, Argent AC, Dash BC. Stomatin: a putative cation transport regulator in the red cell membrane. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1225(1):15–25. doi: 10.1016/0925-4439(93)90116-i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zarkowsky HS, Oski FA, Sha’afi R, Shohet SB, Nathan DG. Congenital hemolytic anemia with high sodium, low potassium red cells. I. Studies of membrane permeability. N Engl J Med. 1968;278(11):573–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196803142781101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bianchi G, Ferrari P, Trizio D, Ferrandi M, Torielli L, Barber BR, et al. Red blood cell abnormalities and spontaneous hypertension in the rat. A genetically determined link. Hypertension. 1985;7(3 Pt 1):319–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Innes DS, Sinard JH, Gilligan DM, Snyder LM, Gallagher PG, Morrow JS. Exclusion of the stomatin, alpha-adducin and beta-adducin loci in a large kindred with dehydrated hereditary stomatocytosis. Am J Hematol. 1999;60(1):72–4. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8652(199901)60:1<72::aid-ajh13>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Montel-Hagen A, Sitbon M, Taylor N. Erythroid glucose transporters. Curr Opin Hematol. 2009;16(3):165–72. doi: 10.1097/MOH.0b013e328329905c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Khan AA, Hanada T, Mohseni M, Jeong JJ, Zeng L, Gaetani M, et al. Dematin and adducin provide a novel link between the spectrin cytoskeleton and human erythrocyte membrane by directly interacting with glucose transporter-1. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(21):14600–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707818200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Ling E, Gardner K, Bennett V. Protein kinase C phosphorylates a recently identified membrane skeleton-associated calmodulin-binding protein in human erythrocytes. J Biol Chem. 1986;261(30):13875–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Fukata Y, Oshiro N, Kinoshita N, Kawano Y, Matsuoka Y, Bennett V, et al. Phosphorylation of adducin by Rho-kinase plays a crucial role in cell motility. J Cell Biol. 1999;145(2):347–61. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.2.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kimura K, Fukata Y, Matsuoka Y, Bennett V, Matsuura Y, Okawa K, et al. Regulation of the association of adducin with actin filaments by Rho-associated kinase (Rho-kinase) and myosin phosphatase. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(10):5542–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.10.5542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kuhlman PA, Fowler VM. Purification and characterization of an alpha 1 beta 2 isoform of CapZ from human erythrocytes: cytosolic location and inability to bind to Mg2+ ghosts suggest that erythrocyte actin filaments are capped by adducin. Biochemistry. 1997;36(44):13461–72. doi: 10.1021/bi970601b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Porro F, Costessi L, Marro ML, Baralle FE, Muro AF. The erythrocyte skeletons of beta-adducin deficient mice have altered levels of tropomyosin, tropomodulin and EcapZ. FEBS Lett. 2004;576(1–2):36–40. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.08.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Marro ML, Scremin OU, Jordan MC, Huynh L, Porro F, Roos KP, et al. Hypertension in beta-adducin-deficient mice. Hypertension. 2000;36(3):449–53. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.36.3.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Robledo RF, Ciciotte SL, Gwynn B, Sahr KE, Gilligan DM, Mohandas N, et al. Targeted deletion of alpha-adducin results in absent beta- and gamma-adducin, compensated hemolytic anemia, and lethal hydrocephalus in mice. Blood. 2008;112(10):4298–307. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-156000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sahr KE, Lambert AJ, Ciciotte SL, Mohandas N, Peters LL. Targeted deletion of the gamma-adducin gene (Add3) in mice reveals differences in alpha-adducin interactions in erythroid and non erythroid cells. Am J Hematol. 2009;84(6):354–61. doi: 10.1002/ajh.21427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]