Abstract

There are two RNA worlds. The first is the primordial RNA world, a hypothetical era when RNA served as both information and function, both genotype and phenotype. The second RNA world is that of today's biological systems, where RNA plays active roles in catalyzing biochemical reactions, in translating mRNA into proteins, in regulating gene expression, and in the constant battle between infectious agents trying to subvert host defense systems and host cells protecting themselves from infection. This second RNA world is not at all hypothetical, and although we do not have all the answers about how it works, we have the tools to continue our interrogation of this world and refine our understanding. The fun comes when we try to use our secure knowledge of the modern RNA world to infer what the primordial RNA world might have looked like.

Studying the numerous roles of RNA today—from catalysis and translation to gene regulation and host defense—may help us infer what the primordial RNA world looked like four billion years ago.

1. THE PRIMORDIAL RNA WORLD

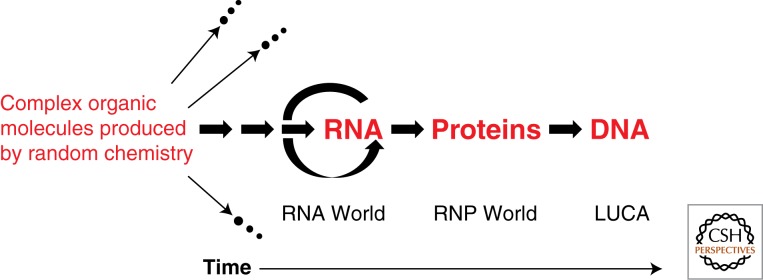

The term “RNA world” was first coined by Gilbert (1986), who was mainly interested in how catalytic RNA might have given rise to the exon–intron structure of genes. But the concept of RNA as a primordial molecule is older, hypothesized by Crick (1968), Orgel (1968), and Woese (1967). Noller subsequently provided evidence that ribosomal RNA is more important than ribosomal proteins for the function of the ribosome, giving experimental support to these earlier speculations (Noller and Chaires 1972; Noller 1993). The discovery of RNA catalysis (Kruger et al. 1982; Guerrier-Takada et al. 1983) provided a much firmer basis for the plausibility of an RNA world, and speculation was rekindled. The ability to find a broad range of RNA catalysts by selection of RNAs from large random-sequence libraries (SELEX) (Ellington and Szostak 1990; Tuerk and Gold 1990; Wright and Joyce 1997) fueled the enthusiasm, and made it possible to conceive of a ribo-organism that carried out complex metabolism (Benner et al. 1989). The widely accepted order of events for the evolution of an RNA world and from the RNA world to contemporary biology is summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

An RNA world model for the successive appearance of RNA, proteins, and DNA during the evolution of life on Earth. Many isolated mixtures of complex organic molecules failed to achieve self-replication, and therefore died out (indicated by the arrows leading to extinction.) The pathway that led to self-replicating RNA has been preserved in its modern descendants. Multiple arrows to the left of self-replicating RNA cover the likely self-replicating systems that preceded RNA. Proteins large enough to self-fold and have useful activities came about only after RNA was available to catalyze peptide ligation or amino acid polymerization, although amino acids and short peptides were present in the mixtures at far left. DNA took over the role of genome more recently, although still >1 billion years ago. LUCA (Last Universal Common Ancestor) already had a DNA genome and carried out biocatalysis using protein enzymes as well as RNP enzymes (such as the ribosome) and ribozymes.

Did an RNA world exist? Some of the most persuasive arguments in favor of an RNA world are as follows. First, RNA is both an informational molecule and a biocatalyst—both genotype and phenotype—whereas protein has extremely limited ability to transmit information (as with prions). Thus, RNA should be capable of replicating itself, and indeed RNA can perform the sort of chemistry required for RNA replication (Cech 1986). Second, it is more parsimonious to conceive of a single type of molecule replicating itself than to posit that two different molecules (such as a nucleic acid and a protein capable of replicating that nucleic acid) were synthesized by random chemical reactions in the same place at the same time. Third, the ribosome uses RNA catalysis to perform the key activity of protein synthesis in all extant organisms, so it must have done so in the Last Universal Common Ancestor (LUCA). Fourth, other catalytic activities of RNA—activities that RNA would need in an RNA world but that have not been found in contemporary RNAs—are generally already present in large combinatorial libraries of RNA sequences and can be discovered by SELEX. Fifth, RNA clearly preceded DNA, because multiple enzymes are dedicated to the biosynthesis of the ribonucleotide precursors of RNA, whereas deoxyribonucleotide biosynthesis is derivative of ribonucleotide synthesis, requiring only two additional enzymatic activities (thymidylate synthase and ribonucleotide reductase.) Finally, a primordial RNA world has the attractive feature of continuity; it could evolve into contemporary biology by the sort of events that are well precedented, whereas it is unclear how a self-replicating system based on completely unrelated chemistry could have been supplanted by RNA.

Opinions vary, however, as to whether RNA comprised the first autonomous self-replicating system or was a derivative of an earlier system. Benner et al. (2010) and Robertson and Joyce (2010) are circumspect, noting that the complexity and the chiral purity of modern RNA create challenges for thinking about it arising de novo. On the other hand, the recent finding that activated pyrimidine ribonucleotides can be synthesized under plausible prebiotic conditions (Powner et al. 2009) means that it is premature to dismiss the RNA-first scenarios. Yarus (2010), an unabashed enthusiast for an RNA world, argues for a closely related replicative precursor. In vitro evolution studies directed towards an RNA replicase ribozyme continue apace and are of great importance in establishing the biochemical plausibility of RNA-catalyzed RNA replication (Johnston et al. 2001; Zaher and Unrau 2007; Lincoln and Joyce 2009; Shechner et al. 2009).

What might the first ribo-organism have looked like? Schrum et al. (2010) describe progress in achieving replication of simple nucleic acid-like polymers within lipid envelopes, thereby constituting “protocells.” These liposomes can grow and upon agitation can divide to give daughter protocells, carrying newly replicated nucleic acids. Whether by lipids or other means, some form of encapsulation must have been a key early step in life. Encapsulation can protect the genome from degradation and predation, allows useful small molecules to be concentrated for the cell's use, and enables natural selection by ensuring that the benefit of newly derived functions accrues to the organism that stumbled across them.

2. THE CONTEMPORARY RNA WORLD

Today, RNA is the central molecule in gene expression in all extant life, serving as the messenger. It is also central to biocatalysis, seen dramatically in the ribosome but also in ribozymes and RNPzymes such as telomerase and the signal recognition particle. More recently, its diverse roles in regulation of (DNA) gene expression have been discovered. It is useful to organize the discussion of contemporary RNA activities as a spectrum, going from those activities that are so RNA-centered that one could conceive of them having operated in a primordial RNA world very much as they do today, to those that rely more and more on collaboration with proteins, to those RNAs that work on DNA (Fig. 1).

What can RNA do by itself? It can bind small metabolites (such as guanine, S-adenosylmethionine, and lysine) with exquisite specificity, and then use this binding energy to switch from one RNA structure to another. These riboswitches are common regulators of gene expression in Gram-positive bacteria, and are also found in other organisms including plants (Breaker 2010; Garst et al. 2010). Furthermore, even very small RNAs can act as ribozymes, accomplishing sequence-specific self-cleavage (Ferré-D'Amaré and Scott 2010). These self-cleavers can be easily re-engineered into multiple-turnover RNA-cleaving enzymes, so it is straightforward to imagine that they could have served such a function in a primordial RNA world. Larger ribozymes can accomplish sophisticated RNA splicing reactions, as described for group II introns by Lambowitz and Zimmerly (2010). There are a number of similarities, both mechanistic and structural, between group II intron self-splicing and spliceosomal splicing of mRNA introns, providing a plausible continuum from the RNA world to post-protein contemporary biology.

Although RNA can perform many activities by itself, in modern cells RNA more often works in concert with proteins. The ribosome uses both RNA and protein to catalyze message-encoded protein synthesis. Yet the heart of the peptidyl transferase center is a ribozyme, and other fundamental activities such as mRNA start-site selection, codon–anticodon interaction, and decoding involve direct RNA–RNA interactions, so the RNA world ancestry of the ribosome is apparent (Moore and Steitz 2010; Noller 2010; Ramakrishnan 2010). The same can be said of the spliceosome (Will and Lührmann 2010). Although a detectable level of catalysis of an isolated step of RNA splicing can be achieved with pure snRNAs (Valadkhan et al. 2009), the efficient and regulated splicing of an entire genome's collection of primary transcripts requires the collaboration of almost 200 proteins and five snRNAs in the modern spliceosome. Telomerase represents another paradigm, as it includes a canonical protein enzyme (TERT) that operates in intimate collaboration with RNA (Blackburn and Collins 2010)—so it appears to derive from more recent evolution, after protein enzymes and DNA chromosomes were well established.

It seems likely that the most recently evolved functions of RNA involve regulation of DNA—because there would have been no DNA to regulate in a primordial RNA world! Nevertheless, similar principles could have been active in an RNA world. Gottesman and Storz (2010) describe RNA regulation in bacteria, which occurs through a range of mechanisms ranging from the simple “antisense RNA” principle of inhibition by complementary base-pairing to RNA–protein interactions. In eukaryotes, several classes of noncoding RNAs perform diverse functions in the regulation of gene expression. Small double-stranded RNAs (for example, the 21-bp small-interfering RNAs and the microRNAs) regulate the stability or the translatability of mRNAs (Joshua-Tor and Hannon 2010). Here the RNA provides such a simple function—recognition of complementary sequences on the mRNA target—that the authors choose to organize their discussion according to subfamilies of the Argonaute proteins that bind the small RNAs. The RNA interference (RNAi) pathway is involved not only in mRNA-level events, but also in the regulation of chromatin structure as described by Volpe and Martienssen (2010). Maintenance of the highly condensed heterochromatin found at chromosome centromeres depends on this RNAi activity. Finally, long noncoding RNAs usually acting in cis (on the chromosome or the local region where they were synthesized) can turn off gene expression by attracting proteins that modify chromatin structure. The effect can spread to an entire chromosome, in the case of the Xist RNA that condenses one of the two X chromosomes in female mammals and thereby gives gene dosage compensation (Lee 2010). In other cases, the effect is more local, affecting transcription of a single gene or a group of genes (Wang et al. 2010). These recently discovered activities of RNA show that the RNA world never stopped (and has not stopped) evolving.

Diverse viral encoded ncRNAs are used as weapons either to circumvent host defense or otherwise manipulate host cellular machinery for their own purposes (Steitz et al. 2010). Although several of the classes of viral ncRNAs are counterparts of cellular equivalents, some are distinctive. Bacteria have evolved the CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeat) defense system to protect themselves from alien DNA such as that injected by bacteriophages (Wang et al. 2010). Here, the information identifying the invading genome is stored in the form of DNA, but it is subsequently converted to small guide RNAs that recognize and interfere with subsequent invaders. Although there is a clear analogy between CRISPR and eukaryotic RNAi, the two systems appear to have evolved completely independently.

3. THE WORLD OF RNA TECHNOLOGY AND MEDICAL APPLICATIONS

I oversimplified when I said that there were two RNA worlds. There is in fact a third—the world of RNA research and development. This third RNA world should be of special interest to students, because this RNA world offers opportunities for gainful employment!

RNA function depends on its structure—it is the seemingly limitless variety of structures that allows so many diverse functions. We can now predict RNA secondary structure quite well (Mathews et al. 2010) and see much progress on predicting 3D structure (Westhof et al. 2010). Remarkably, we can now watch molecules of RNA fold and unfold and switch from one state to another in “single-molecule experiments” (Tinoco et al. 2010). We can use double-stranded RNAs and the intrinsic RNAi machinery present in organisms to do genome-wide knock-downs of gene function (Perrimon et al. 2010). Finally, RNA science is poised to make an impact on medicine. For example, aptamers can monitor the concentrations of many of the proteins in human serum, which has diagnostic applications because the presence of many proteins is correlated with health and disease (Gold et al. 2010). In addition, both microRNAs and antisense nucleic acids that inhibit miRNAs have pharmaceutical potential, which is under development in numerous biotechnology and pharmaceutical companies.

Thus, the authors of this collection take us on a fascinating journey through three RNA worlds. The primordial RNA world (ca. four billion years ago) relied on the dual ability of RNA to serve as both informational molecule and biocatalyst, providing a self-replicating system. Coupled with other ribozymes that carried out complex metabolism and encapsulated in some sort of envelope, self-replicating RNA constituted an early life form that was the ancestor of contemporary biology. The second RNA world is that of contemporary biology, where RNA occasionally acts by itself (ribozymes and riboswitches) but more often acts in concert with proteins. The ribosome and the spliceosome still “remember” their ribozyme heritage, whereas telomerase and the signal recognition particle have moved on to incorporate canonical protein enzymes. The RNA interference system and CRISPR have gone further, reducing the role of the RNA to that of a simple guide sequence. Finally, the third RNA world—that of RNA technology and medical applications—is a baby compared to even the second RNA world, because it arose only in the past half-century. Although this last RNA world is only perhaps one millionth of one per cent as old as the primordial RNA world, it is a vibrant community, and I feel privileged to be part of it.

Footnotes

Editors: John F. Atkins, Raymond F. Gesteland, and Thomas R. Cech

Additional Perspectives on RNA Worlds available at www.cshperspectives.org

REFERENCES

- Benner SA, Ellington AD, Tauer A 1989. Modern metabolism as a palimpsest of the RNA world. Proc Natl Acad Sci 86: 7054–7058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benner SA, Kim H-J, Yang Z 2010. Setting the Stage: The history, chemistry, and geobiology behind RNA. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 10.1101/cshperspect.a003541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn EH, Collins K 2010. Telomerase: An RNP enzyme synthesizes DNA. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 10.1101/cshperspect.a003558 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breaker RR 2010. Riboswitches and the RNA world. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 10.1101/cshperspect.a003566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cech TR 1986. A model for the RNA-catalyzed replication of RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci 83: 4360–4363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crick FH 1968. The origin of the genetic code. J Mol Biol 38: 367–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellington AD, Szostak JW 1990. In vitro selection of RNA molecules that bind specific ligands. Nature 346: 818–822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferré-D'Amaré AR, Scott WG 2010. Small self-cleaving ribozymes. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 10.1101/cshperspect.a003574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garst AD, Edwards AL, Batey RT 2010. Ribswitches: Structures and mechanisms. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 10.1101/cshperspect.a003533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert W 1986. Origin of life: The RNA world. Nature 319: 618 [Google Scholar]

- Gold L, Janjic N, Jarvis T, Schneider D, Walker JJ, Wilcox SK, Zichi D 2010. Aptamers and the RNA world, past and present. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 10.1101/cshperspect.a003582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottesman S, Storz G 2010. Bacterial small RNA regulators: Versatile roles and rapidly evolving variations. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 10.1101/cshperspect.a003798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrier-Takada C, Gardiner K, Marsh T, Pace N, Altman S 1983. The RNA moiety of ribonuclease P is the catalytic subunit of the enzyme. Cell 35: 849–857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston WK, Unrau PJ, Lawrence MS, Glasner ME, Bartel DP 2001. RNA-catalyzed RNA polymerization: Accurate and general RNA-templated primer extension. Science 292: 1319–1325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshua-Tor L, Hannon GJ 2010. Ancestral roles of small RNAs: An ago-centric perspective. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 10.1101/cshperspect.a003772 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruger K, Grabowski PJ, Zaug AJ, Sands J, Gottschling DE, Cech TR 1982. Self-splicing RNA: Autoexcision and autocyclization of the ribosomal RNA intervening sequence of Tetrahymena. Cell 31: 147–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambowitz AM, Zimmerly S 2010. Group II introns: Mobile ribozymes that invade DNA. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 10.1101/cshperspect.a003616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JT 2010. The X as model for RNA's niche in epigenomic regulation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 10.1101/cshperspect.a003749 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln TA, Joyce GF 2009. Self-sustained replication of an RNA enzyme. Science 323: 1229–1232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathews DH, Moss WN, Turner DH 2010. Folding and finding RNA secondary structure. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 10.1101/cshperspect.a003665 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore PB, Steitz TA 2010. The roles of RNA in the synthesis of protein. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 10.1101/cshperspect.a003780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noller HF 2010. Evolution of protein synthesis from an RNA world. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 10.1101/cshperspect.a003681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noller HF 1993. Peptidyl transferase: Protein, ribonucleoprotein, or RNA? J Bacteriol 175: 5297–5300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noller HF, Chaires JB 1972. Functional modification of 16S ribosomal RNA by kethoxal. Proc Natl Acad Sci 69: 3115–3118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orgel LE 1968. Evolution of the genetic apparatus. J Mol Biol 38: 381–393 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrimon N, Ni J-Q, Perkins L 2010. In vivo RNAi: Today and tomorrow. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 10.1101/cshperspect.a003640 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powner MW, Gerland B, Sutherland JD 2009. Synthesis of activated pyrimidine ribonucleotides in prebiotically plausible conditions. Nature 459: 239–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramakrishnan V 2010. The ribosome: Some hard facts about its structure and hot air about its evolution. In RNA Worlds (eds. Atkins JF, Gesteland RF, Cech TR). Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson MP, Joyce GF 2010. The origins of the RNA world. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 10.1101/cshperspect.a003608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrum JP, Zhu TF, Szostak JW 2010. The origins of cellular life. In RNA Worlds (eds. Atkins JF, Gesteland RF, Cech TR). Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shechner DM, Grant RA, Bagby SC, Koldobskaya Y, Piccirilli JA, Bartel DP 2009. Crystal structure of the catalytic core of an RNA-polymerase ribozyme. Science 326: 1271–1275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steitz J, Borah S, Cazalla D, Fok V, Lytle R, Mitton-Fry R, Riley K, Samji T 2010. Noncoding RNPs of viral origin. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 10.1101/cshperspect.a005165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinoco I, Chen G, Qu X 2010. RNA reactions one molecule at a time. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 10.1101/cshperspect.a003624 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuerk C, Gold L 1990. Systematic evolution of ligands by exponential enrichment: RNA ligands to bacteriophage T4 DNA polymerase. Science 249: 505–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valadkhan S, Mohammadi A, Jaladat Y, Geisler S 2009. Protein-free small nuclear RNAs catalyze a two-step splicing reaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106: 11901–11906 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volpe T, Martienssen RA 2010. RNA interference and heterochromatin assembly. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 10.1101/cshperspect.a003731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Song X, Glass CK, Rosenfeld MG 2010. The long arm of long noncoding RNAs: Roles as sensors regulating gene transcriptional programs. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 10.1101/cshperspect.a003756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westhof E, Masquida B, Jossinet F 2010. Predicting and modeling RNA architecture. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 10.1101/cshperspect.a003632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Will CL, Lührmann R 2010. Spliceosome structure and function. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 10.1101/cshperspect.a003707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woese CR 1967. The genetic code: The molecular basis for genetic expression. p. 186 Harper & Row [Google Scholar]

- Wright MC, Joyce GF 1997. Continuous in vitro evolution of catalytic function. Science 276: 614–617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarus M 2010. Getting past the RNA world: The initial Darwinian ancestor. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 10.1101/cshperspect.a003590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaher HS, Unrau PJ 2007. Selection of an improved RNA polymerase ribozyme with superior extension and fidelity. RNA 13: 1017–1026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]