Abstract

Purpose.

Mutations in either retinoid isomerase (RPE65) or lecithin-retinol acyltransferase (LRAT) lead to Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA). By using the Lrat–/– mouse model, previous studies have shown that the rapid cone degeneration in LCA was caused by endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress induced by S-opsin aggregation. The purpose of this study is to examine the efficacy of an ER chemical chaperone, tauroursodeoxycholic acid (TUDCA), in preserving cones in the Lrat–/– model.

Methods.

Lrat–/– mice were systemically administered with TUDCA and vehicle (0.15 M NaHCO3) every 3 days from P9 to P28. Cone cell survival was determined by counting cone cells on flat-mounted retinas. The expression and subcellular localization of cone-specific proteins were analyzed by western blotting and immunohistochemistry, respectively.

Results.

TUDCA treatment reduced ER stress and apoptosis in Lrat–/– retina. It significantly slowed down cone degeneration in Lrat–/– mice, resulting in a ∼3-fold increase in cone density in the ventral and central retina as compared with the vehicle-treated mice at P28. Furthermore, TUDCA promoted the degradation of cone membrane–associated proteins by enhancing the ER-associated protein degradation pathway.

Conclusions.

Systemic injection of TUDCA is effective in reducing ER stress, preventing apoptosis, and preserving cones in Lrat–/– mice. TUDCA has the potential to lead to the development of a new class of therapeutic drugs for treating LCA.

This work showed that TUDCA is effective in reducing ER stress, preventing apoptosis, and preserving cones in a mouse model of LCA (Lrat–/–).

Introduction

Retinoid isomerase (RPE65) and lecithin-retinol acyltransferase (LRAT) are key enzymes in the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) required for 11-cis retinal recycling. LRAT catalyzes the esterification of all-trans retinol to all-trans retinyl esters,1 which in turn are the substrates for the retinoid isomerase, RPE65, to produce 11-cis retinol.2–4 Mutations in RPE65 or LRAT cause Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA), the most severe retinal dystrophy causing visual impairment in early childhood.5–8 RPE65-LCA (LCA2) is more common than LRAT-LCA.5 Two mouse models, Rpe65–/– and Lrat–/–, capture many salient pathologic features of human LCA.9–11 Both rod and cone functions are severely compromised due to the lack of 11-cis retinal.9,10 Apo-rhodopsin is transported normally to the rod outer segments (ROS) and the rod photoreceptors degenerate slowly (>10 months). In contrast, the cone opsins (S-opsin and M-opsin) fail to traffic from the cone inner segment to the cone outer segment (COS) and the cone photoreceptors in the central/ventral regions degenerate rapidly (<4 weeks).11–14 Concomitantly, cone membrane–associated proteins—e.g., cone transducin α-subunit (Gαt2), cone phosphodiesterase 6α′ (PDE6α′), and G-protein–coupled receptor kinase 1 (GRK1)—are not transported to the outer segment properly and are degraded. Early loss of foveal cones also occurs in RPE65-deficient patients.15,16 Rod degeneration is caused by the constitutive activity of the rhodopsin apoprotein,17 while rapid cone degeneration is caused by endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress induced by S-opsin aggregation.18

In this work, we examine the efficacy of an ER chemical chaperone, tauroursodeoxycholic acid (TUDCA), in preventing the rapid cone degeneration in the Lrat–/– model. TUDCA is a hydrophilic bile acid, which has been shown to be effective in alleviating ER stress and preventing apoptosis in many disease models, including type 2 diabetes,19 hereditary hemochromatosis20 acute kidney injury,21 acute pancreatitis,22 retinal degeneration,23–28 Alzheimer's disease,29–34 and Parkinson's disease.35 This study indicates that systemic injection of TUDCA is effective in reducing ER stress, preventing apoptosis, and preserving cones in Lrat–/– mice.

Methods

Animals and TUDCA Injection

Lrat–/– mice were generated and described previously.10 WT (C57BL/6J) mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory. All animal experiments were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the University of Utah and were performed in accordance with the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animal in Ophthalmic and Vision Research. Mice were reared under cyclic light (12-hour light/12-hour dark).

Lrat–/– and WT mice were treated with TUDCA (TCI America) or vehicle (0.15 M NaHCO3, pH 7.0) following a published procedure.25 Several studies showed that subcutaneous injection of TUDCA (500 mg/kg b.w.) every 3 days preserved the structure and function of both cone and rod in mouse models of retinitis pigmentosa.24–26,28 Thus, the same dose and injection schedule was adopted in this study. Mice were weighed and injected subcutaneously at the nape of the neck starting at P9. The starting date of P9 was selected because others have shown that early intervention by TUDCA is crucial to avoid treatment variability.36

Cone Cell–Density Analysis in Flatmounted Retinas

Retinal flatmounts were prepared as described previously,12,14 except that cone arrestin was used to label cone cells. Briefly, eyes were fixed in 4% formaldehyde solution in PBS for 10 minutes. After removing the cornea, iris, lens, and RPE-choroid, retinas were fixed for 2 hours. After three washes with PBS, the retinas were incubated with a blocking buffer (0.6% triton X-100, 1% BSA in PBS) for 1 hour. The retinas were incubated with a cone arrestin antibody14 overnight at 4°C. After washing three more times with PBS, retinas were incubated with Cy3-conjugated goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody. Retinas were again washed three times in PBS, mounted on a slide, and cover-slipped. Samples were viewed with a confocal microscope (Olympus FV1000; Olympus America Inc., Center Valley, PA). Cones were counted from three retinal areas: central (within 500 μm of the optic nerve), dorsal, and ventral. Data were expressed as the mean number of cones/mm2 ± SEM.

Immunohistochemistry

The immunohistochemical procedure was performed as previously described.14,18,37 Cryostat sections (10–15 μm) were incubated with various primary antibodies, and were visualized with Alexa 488- or Cy3-conjugated secondary antibodies. Nuclear dye DAPI was included in the secondary antibodies. The following primary antibodies were used, anti-M-opsin (AB5405) from Millipore, anti-S-opsin (MBO) (generous gift of J. Chen, USC);38 anti-CHOP (L63F7); anti-active-caspase-3 (#9669) from Cell Signaling Technology; anti-GRK1 (SC-13,078); anti-Gαt2 (SC-390) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology; anti-cone-arrestin (prepared according to reference 39); and monoclonal anti-rhodopsin antibody1D4 (generous gift of R. Molday, UBC, Vancouver, Canada).

Western Blot

Retinas from both eyes of the mouse were sonicated in 150 μL of radio-immunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (150 mM NaCl, 1.0% IGEPAL CA-630, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% SDS, and 50 mM Tris, pH 8.0) plus a protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Protein concentration was measured by Bio-Rad protein assay kit; 15 μg of protein from each sample was loaded for SDS-PAGE, except that samples were diluted 100 times for detecting rhodopsin. The primary antibodies were detected with goat anti-rabbit or anti-mouse secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase. The primary antibodies were the same as used in immunohistochemistry. Additional immunoblot antibodies were monoclonal anti-Gαt1/Gαt2 (TF15, Cytosignal) (the amount of Gαt2 from cones is negligible in comparison with Gαt1 from rods on western), anti-PDE6α′ (generous gift of T. Li, NEI), rabbit monoclonal anti-VCP (EPR3307[2]; Epitomics, Inc., Burlingame, CA), and anti-β-actin (AC-15; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO).

Statistics

Data were presented as mean ± SEM, and the differences were analyzed with unpaired two-sample Student's t-test. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

TUDCA Significantly Slows Down Cone Degeneration in Lrat–/– Mice

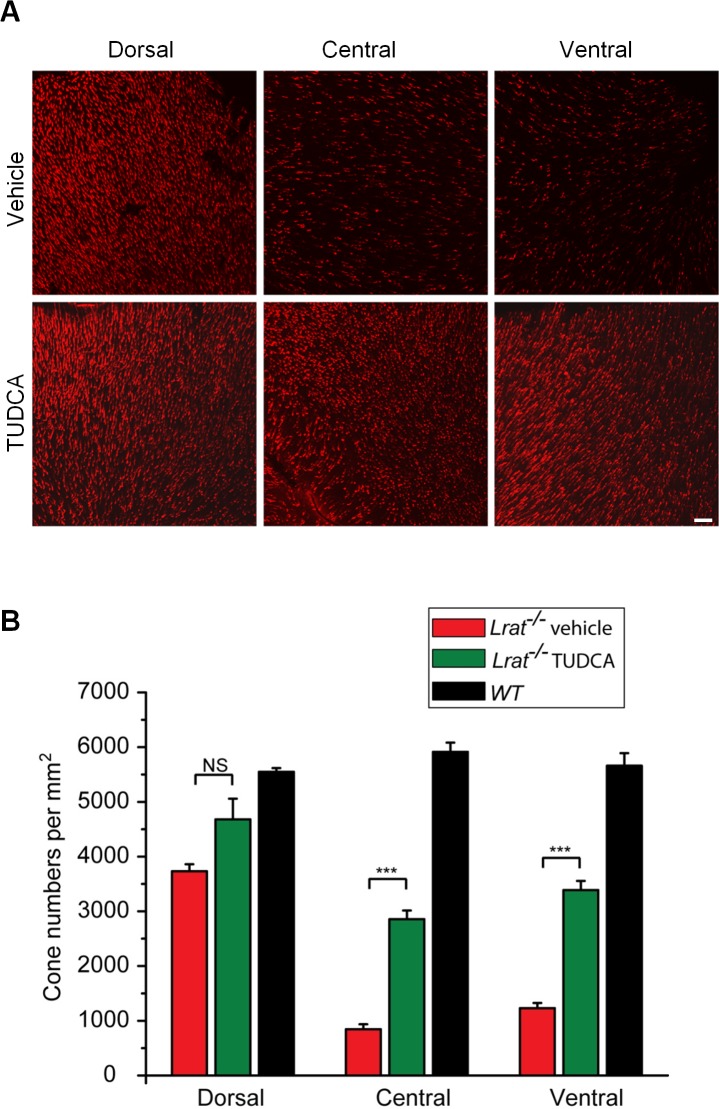

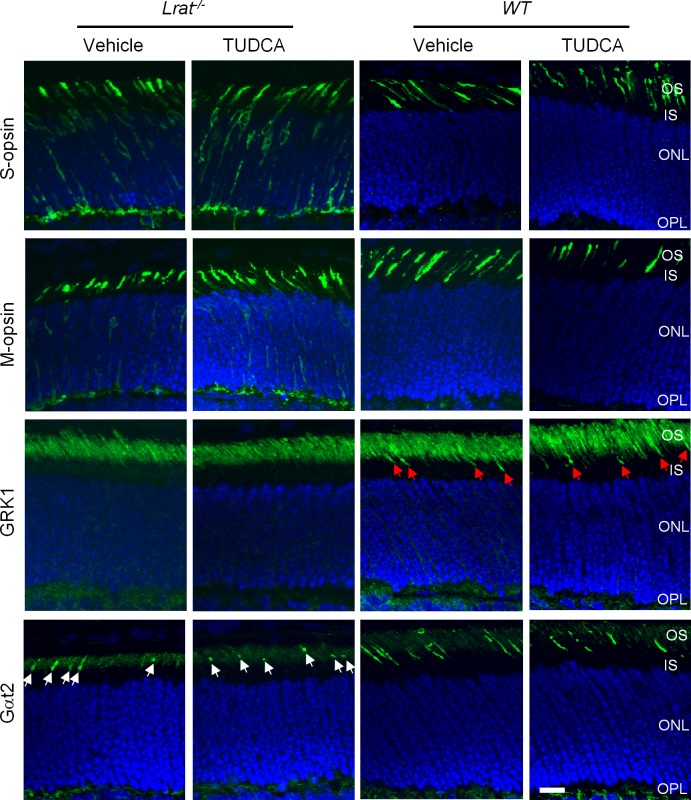

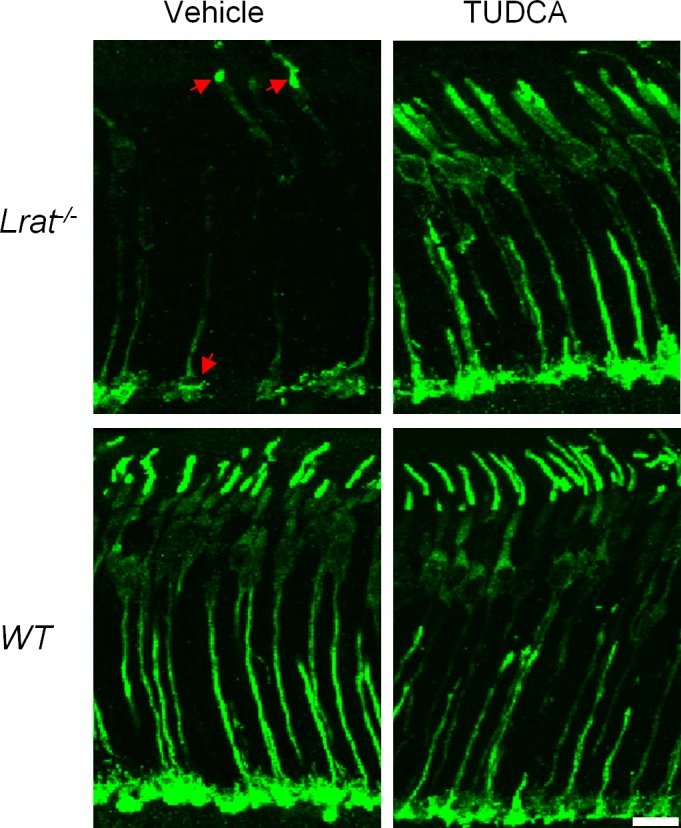

Cone photoreceptors degenerate rapidly in Lrat–/– mice.11–14 To determine whether TUDCA can prevent or slow down this rapid cone degeneration, Lrat–/– mice were injected subcutaneously once every 3 days starting at P9. Treated mice were euthanized at P28 and cone cell densities were determined at different retinal regions from fluorescence images of cone-arrestin–stained retinal flatmounts. There was significant cone degeneration in the ventral and central regions of retina in vehicle injected Lrat–/– mice (Figs. 1A, 1B), as described previously.11–14 Frozen sections probed with an anti-cone arrestin antibody revealed cone fragments in the inner segment and pedicle area in a few remaining severely degenerate cones (Fig. 2, red arrows). TUDCA treatment resulted in a significant increase (∼3-fold, P < 0.001) in cone density in the ventral and central retina compared with the vehicle (Fig. 1). Cone cell morphology was greatly improved, as evidenced by the presence of intact cone structures (Fig. 2). TUDCA treatment also increased cone numbers (25%) in the dorsal retina, although the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.057). Although TUDCA provided significant protection of central and ventral cones of Lrat–/– mice, the cone densities are still lower than those of WT (54.5% and 62.7% lower for central cones and ventral cones, respectively). In contrast to its protective effect on cones, TUDCA treatment had no effect on rod photoreceptors of P28 Lrat–/– and WT mice in terms of both morphology and cell numbers (indicated by the thickness of the outer nuclear layer (ONL, Fig. 3).

Figure 1. .

Quantification on the protective effect of TUDCA on Lrat–/– cones. (A) Cones of TUDCA or vehicle injected Lrat–/– mice (P28) were visualized by labeling cone arrestin in flatmounted retinas. Scale bar = 50 μm. (B) Cone photoreceptors were counted in the ventral, central, and dorsal sections in TUDCA injected Lrat–/– (n = 8), vehicle-injected Lrat–/– (n = 6), and untreated WT (n = 5). Data were expressed as the average numbers of cones per mm2 (mean ± SEM). Untreated WT mice were included as controls to evaluate the efficacy of TUDCA. ***P < 0.001, NS, not significant.

Figure 2. .

Comparison of cone cell morphology between TUDCA and vehicle-treated P28 mice (Lrat–/– and WT). Cones of TUDCA or vehicle-injected Lrat–/– or WT mice were visualized by labeling cone arrestin in retinal sections. Red arrows indicate a few remaining severely degenerate cones of Lrat–/– mice with “patched” labeling in the outer segments and synaptic pedicels. Scale bar = 10 μm.

Figure 3. .

Effect of TUDCA treatment on rod photoreceptors. (A) P28 Lrat–/– and WT retinal sections were labeled with rhodopsin antibody 1D4 (in red). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar = 20 μm. (B) ONL length was measured from TUDCA-injected Lrat–/– (n = 8), vehicle-injected Lrat–/– (n = 6), TUDCA-injected WT (n = 6), and vehicle-injected WT (n = 6). Data were presented as mean ± SEM. NS, not significant.

TUDCA Reduces ER Stress and Apoptosis in Lrat–/– Retina

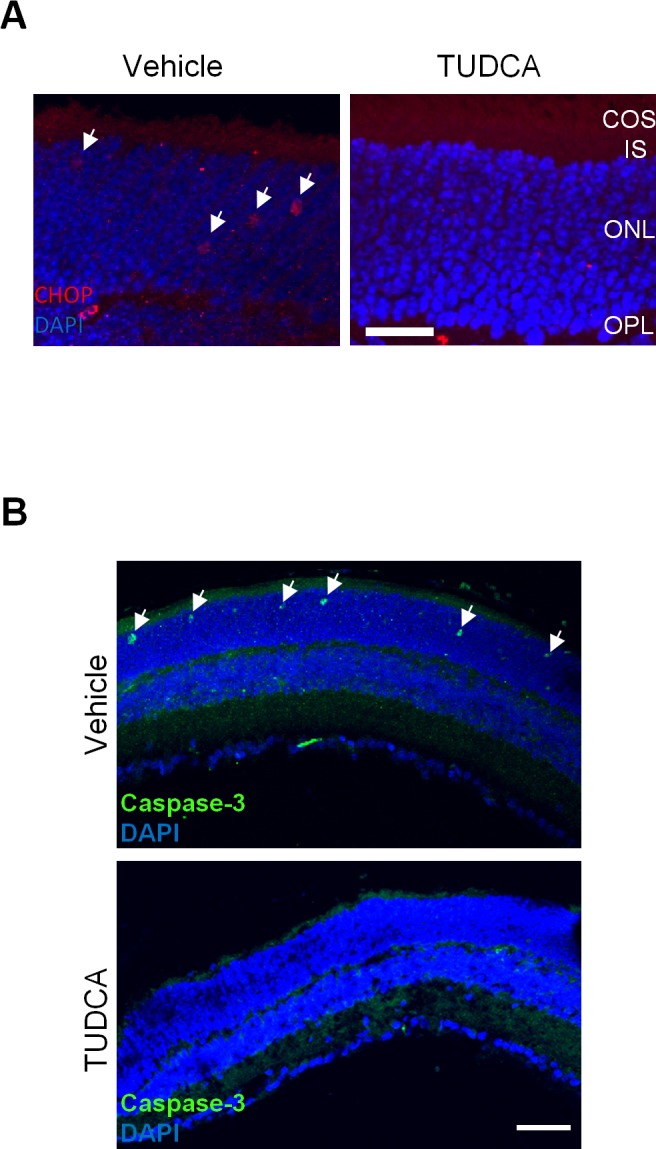

Due to S-opsin aggregation, central and ventral cones are under much more intense ER stress than dorsal cones in the Lrat–/– mice.18 Therefore, this study examined whether TUDCA treatment had an effect on CHOP (C/EBP homology protein, a B-ZIP transcription factor) activation. CHOP is a well-characterized UPR (unfolded protein response) target gene and an ER stress marker associated with apoptosis.40 Indeed, a substantial reduction of CHOP was observed in the ventral retina of TUDCA-treated Lrat–/– mice compared with that in vehicle-treated littermates at P18 (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, the TUDCA injection virtually eliminated apoptotic signals in the ONL of Lrat–/– mice judged by caspase-3 activation (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4. .

Effect of TUDCA treatment on CHOP and caspase-3 activation in Lrat–/– retina. (A) The ventral retinal sections of P18 Lrat–/– mice were labeled with an anti-CHOP antibody (red) and DAPI (blue). White arrows indicate CHOP signals in the ONL of the ventral retina of vehicle-injected Lrat–/– mice. Red signals in the OPL were due to the labeling of retinal vessels by the Cy3-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody. Scale bar = 20 μm. (B) Retinal sections of P18 Lrat−/− mice (vehicle or TUDCA injected) were labeled with an antibody against the active caspase-3 (green) and DAPI (blue). Arrows indicate caspase-3 signals in the ONL of the vehicle-injected mice. Scale bar = 50 μm.

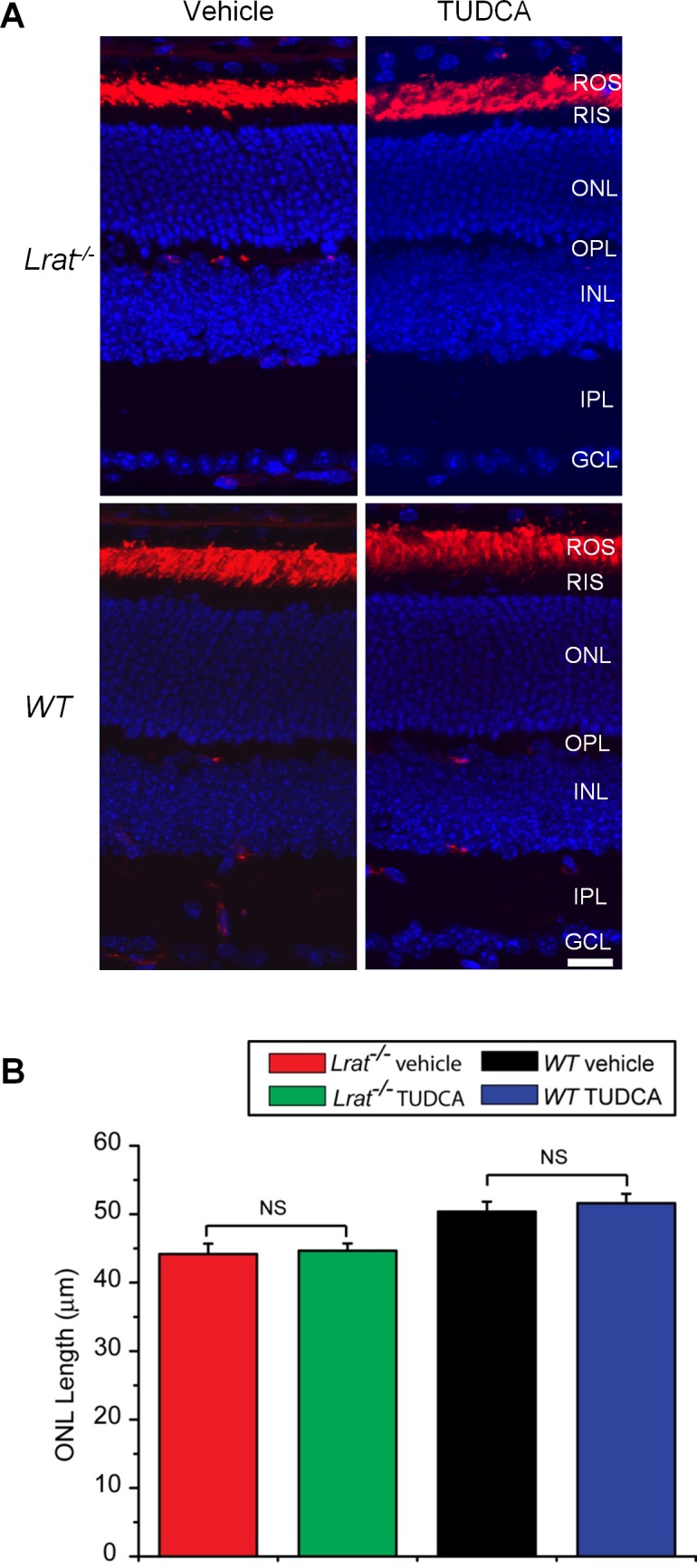

TUDCA Does Not Correct Mistrafficking of Membrane-Associated Proteins in Lrat–/– Cones

Previous work showed that several membrane-associated proteins (e.g., M/S opsins, GRK1, Gαt2) involved in cone phototransduction failed to traffic to the outer segment of Lrat–/– or Rpe65–/– cones.14 The mistrafficked proteins were degraded through a posttranslational mechanism,14 except that S-opsin aggregated and resisted cellular degradation.18 This study examined by immunohistochemistry whether TUDCA could rescue the trafficking of these membrane proteins. In vehicle-injected P18 Lrat–/– mice, transmembrane proteins such as M- and S-opsins were mislocalized in the inner segment, cell body, axon, and synaptic pedicle of cones, as shown previously11,14 (Fig. 5). For peripheral membrane-associated proteins, GRK1 was not detected in Lrat–/– cone outer segment (COS) while the signal of Gαt2 was much reduced similar to the previous work.14 TUDCA treatment did not correct the mistrafficking of either cone transmembrane proteins (S-opsin and M-opsin) or peripheral membrane–associated proteins (Gαt2 and GRK1).

Figure 5. .

Immunolocalization of membrane-associated proteins (S-opsin, M-opsin, GRK1, and Gαt2) in the retinas of TUDCA or vehicle-injected Lrat–/– and WT mice. P18 Lrat–/– and WT retinas were stained with antibodies against S-opsin, M-opsin, GRK1, and Gαt2 (green). Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Red arrows indicate GRK1 signals in the WT (both vehicle and TUDCA treated) COS while white arrows indicate reduced Gαt2 signals in the Lrat–/– COS. Scale bar = 10 μm.

TUDCA Promotes the Degradation of Membrane-Associated Proteins in Lrat–/– Cones

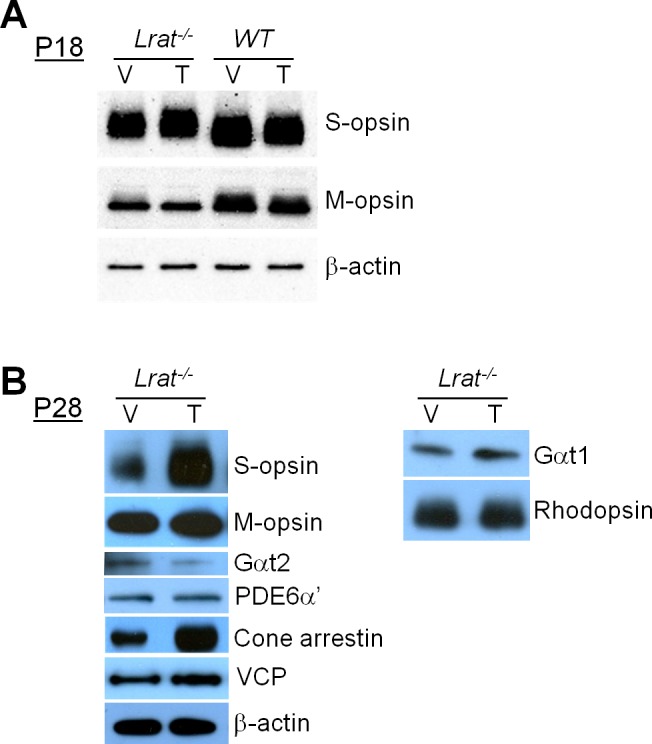

It has been shown previously that S-opsin aggregation causes rapid central/ventral cone degeneration in Lrat–/– mice.18 This study then examined by immunoblot the possibility that TUDCA exerted its protective effect on Lrat–/– cones by reducing S-opsin aggregation. At P18, an early stage of cone degeneration, M-opsin was markedly reduced, whereas S-opsin accumulated in Lrat–/– cones as previously described18 (vehicle-injected Lrat–/– versus vehicle-injected WT, Fig. 6A). TUDCA treatment made no difference in the protein levels of M- and S-opsins in either Lrat–/– or WT mice, suggesting TUDCA did not reduce S-opsin aggregation. As shown previously by study authors18 and others,41 S-opsin of Lrat–/– cones (both vehicle and TUDCA treated) exhibited slower mobility in SDS-PAGE compared with WT S-opsin (Fig. 6A), which was attributed to incomplete N-glycan processing.41 Misfolded S-opsin aggregates in the ER, which may prevent the normal N-glycan trimming in the Golgi, resulted in higher molecular-weight products. However, the nature and significance of this “mobility shift” deserves further study. At P28, an advanced stage of cone degeneration, TUDCA treated Lrat–/– retina contained far more S-opsin and cone arrestin than vehicle controls (Fig. 6B), consistent with a significant increase of cone numbers in the central and ventral retina (Fig. 1). Surprisingly, an increase of other COS proteins (e.g., M-opsin, Gαt2, and PDE6α′) was not observed, despite the large increase of cone numbers in TUDCA-treated Lrat–/– retina. In fact, the level of Gαt2 decreased in TUDCA-treated Lrat–/– retina. This result suggests that TUDCA promotes the degradation of COS proteins (except S-opsin) in Lrat–/– cones (see more in Discussion). In contrast to Lrat–/– cones, TUDCA had no effect on protein stability of membrane-associated proteins in Lrat–/– rods (i.e., Gαt1 and rhodopsin) (Fig. 6B). TUDCA may promote the degradation of COS proteins by enhancing the ER-associated degradation (ERAD) pathway. To examine this possibility, this study compared the expression level of valosin-containing protein (VCP/P97)—an important component of the ERAD machinery that provides the main driving force for extraction of poly-ubiquitinated ERAD substrates through the ER membrane42,43—in retinal extracts between TUDCA and vehicle-treated Lrat–/– mice. Western blotting analysis showed that TUDCA increased the level of VCP (Fig. 6B), indicating enhanced ERAD.

Figure 6. .

Western blotting analysis of various proteins in the retinas. (A) P18 Lrat–/– and WT mice. (B) P28 Lrat–/– mice. Mice were injected with vehicle or TUDCA. The results shown are representative of several blots. β-actin was included as the internal loading controls.

Discussion

In the Lrat–/– LCA model, cone membrane-associated proteins (M-opsin, Gαt2, PDE6α′, and GRK1) fail to traffic properly to the COS and are significantly reduced through a posttranslational mechanism.14 One exception is S-opsin that resists proteasome degradation and aggregates, resulting in ER stress and rapid cone degeneration in the ventral and central retina.18 In this work, an ER chaperone (TUDCA) was used to preserve Lrat–/– cones. Study authors found that TUDCA treatment significantly slowed down ventral and central cone degeneration (Fig. 1). Previous work suggested that cone opsins require 11-cis retinal to fold correctly and to traffic to COS.14 Other COS proteins may require cone opsins as guides to be co-transported and targeted correctly. In the absence of 11-cis retinal, both M-opsin and peripheral membrane–associated proteins (e.g., prenylated PDE6α′ and GRK1, as well as acylated Gαt2), which are processed in the ER, are likely degraded by ERAD. ERAD is an important quality control system in the ER of eukaryotic cells to ensure that only properly folded and assembled proteins (or complexes) are allowed to exit for delivery to their intended sites of function.44,45 Inefficient clearance of misfolded and misassembled proteins from the ER leads to ER stress, which has been implicated in the pathogenesis of several major diseases (e.g., diabetes, inflammation, and neurodegenerative disorders including Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease40). TUDCA enhanced the degradation of COS proteins via ERAD (Fig. 6B) and reduced CHOP activation (Fig. 4A), suggesting that TUDCA protects cones by enhancing the ER's capability in dealing with stress. TUDCA may also protect cones via its potent anti-apoptotic property.36,46 TUDCA has no effect on cytoplasmic proteins (e.g., arrestin) or ROS proteins (e.g., Gαt1 and rhodopsin), probably because the folding and trafficking of these proteins were not affected by the absence of 11-cis retinal, and thus less affected by ERAD. Furthermore, TUDCA neither reduces S-opsin aggregation nor corrects the mistrafficking of membrane-associated proteins in cones, suggesting it does not stabilize the conformations of these proteins (or prevent their aggregation) as other chemical chaperones do.47,48

Currently, there is no FDA-approved treatment to prevent vision loss in LCA2 patients. There are two strategies under active study in the field: gene therapy delivering AAV2-RPE65 by subretinal injection and drug-based therapy by retinoid analogs. Gene therapy offers great promise with successful phase I and II clinical trials.49–54 However, gene therapy has a limited application window, as a virus with a replacement gene must be injected before significant retinal degeneration occurs.52,53 This is especially true in rescuing cones. A recent study concluded that there is no benefit and some risk in treating the cone-rich fovea.54 Moreover, subretinal delivery of AAV-RPE65 is unlikely to cover the entire retina, leaving treated areas vulnerable to secondary degeneration caused by negative bystander effects from neighboring untreated cells.55 Retinoid therapy can rescue both rod and cone function in animal models.11,13,16,56,57 It also produced encouraging results in a phase Ib open label trial.58 However, it is much more difficult to preserve cones than rods. In fact, a recent study showed that retinoid treatment is ineffective in preventing cone degeneration of Rpe65–/– mice raised in normal light/dark cycles and is only effective under constant darkness.59 Therefore, development of novel drugs that prevent or delay the rapid cone degeneration in LCA2 will have considerable impact on the therapeutic strategy. Reagents that can protect cones of untreated regions from degeneration will minimize bystander effects and preserve untreated photoreceptors eligible for future treatment. The results of this study suggest that TUDCA may be a good candidate in treating LCA2 with several advantages: (1) TUDCA is not light sensitive and is therefore effective under normal light-dark cycle; (2) The hydrophilic TUDCA can be delivered to the eye by oral intake; and (3) TUDCA has already been approved for treating various liver and gallbladder diseases with outstanding safety records.60,61 Therefore, TUDCA-based ER chaperones may be used as substitutes to gene therapy for protecting cones of LCA2 patients at very young ages when gene therapy might be too traumatic to the developing eye (i.e., before 4 years). TUDCA may also be used as a supplement to gene therapy at older ages to maximize the preservation of cones. Furthermore, since retinoid therapy is effective in preserving rods while TUDCA may be effective in preserving cones, the combination of the two may be used to protect both rods and cones.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jeannie Chen, Tiansen Li, and Robert S. Molday for providing antibodies. We also thank Sandeep Kumar and Alex D. Jones for discussions and comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supported by a Career Initiation Research Grant Award (TZ) from Knights Templar Eye Foundation, Inc., Flower Mound, Texas; a Research Award (YF) from the E. Matilda Ziegler Foundation for the Blind, Inc., Darien, Connecticut; a Career Development Award (YF), a Senior Investigator Award (WB), and an unrestricted grant to the Department of Ophthalmology at the University of Utah from Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc., New York, New York; NIH Grants EY08123, EY019298, EY014800-039003 (WB); and a grant (WB) from the Foundation Fighting Blindness, Inc., Columbia, Maryland.

Disclosure: T. Zhang, None; W. Baehr, None; Y. Fu, None

References

- 1. Ruiz A, Winston A, Lim YH, Gilbert BA, Rando RR, Bok D. Molecular and biochemical characterization of lecithin retinol acyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:3834–3841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Moiseyev G, Chen Y, Takahashi Y, Wu BX, Ma JX. RPE65 is the isomerohydrolase in the retinoid visual cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:12413–12418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Jin M, Li S, Moghrabi WN, Sun H, Travis GH. Rpe65 is the retinoid isomerase in bovine retinal pigment epithelium. Cell. 2005;122:449–459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Redmond TM, Poliakov E, Yu S, Tsai JY, Lu Z, Gentleman S. Mutation of key residues of RPE65 abolishes its enzymatic role as isomerohydrolase in the visual cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:13658–13663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chung DC, Traboulsi EI. Leber congenital amaurosis: clinical correlations with genotypes, gene therapy trials update, and future directions. J Aapos. 2009;13:587–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stone EM. Leber congenital amaurosis—a model for efficient genetic testing of heterogeneous disorders: LXIV Edward Jackson Memorial Lecture. Am J Ophthalmol 144:791–811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Thompson DA, Li Y, McHenry CL. Mutations in the gene encoding lecithin retinol acyltransferase are associated with early-onset severe retinal dystrophy. Nat Genet. 2001;28:123–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. den Hollander AI, Roepman R, Koenekoop RK, Cremers FP. Leber congenital amaurosis: genes, proteins and disease mechanisms. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2008;27:391–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Redmond TM, Yu S, Lee E, et al. Rpe65 is necessary for production of 11-cis-vitamin A in the retinal visual cycle. Nat Genet. 1998;20:344–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Batten ML, Imanishi Y, Maeda T, et al. Lecithin-retinol acyltransferase is essential for accumulation of all-trans-retinyl esters in the eye and in the liver. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:10422–10432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fan J, Rohrer B, Frederick JM, Baehr W, Crouch RK. Rpe65−/− and Lrat−/− mice: comparable models of leber congenital amaurosis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:2384–2389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Znoiko SL, Rohrer B, Lu K, Lohr HR, Crouch RK, Ma JX. Downregulation of cone-specific gene expression and degeneration of cone photoreceptors in the Rpe65-/- mouse at early ages. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:1473–1479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rohrer B, Lohr HR, Humphries P, Redmond TM, Seeliger MW, Crouch RK. Cone opsin mislocalization in Rpe65-/- mice: a defect that can be corrected by 11-cis retinal. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:3876–3882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhang H, Fan J, Li S. Trafficking of membrane-associated proteins to cone photoreceptor outer segments requires the chromophore 11-cis-retinal. J Neurosci. 2008;28:4008–4014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jacobson SG, Aleman TS, Cideciyan AV. Human cone photoreceptor dependence on RPE65 isomerase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:15123–15128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Maeda T, Cideciyan AV, Maeda A. Loss of cone photoreceptors caused by chromophore depletion is partially prevented by the artificial chromophore pro-drug, 9-cis-retinyl acetate. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:2277–2287 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Woodruff ML, Wang Z, Chung HY, Redmond TM, Fain GL, Lem J. Spontaneous activity of opsin apoprotein is a cause of Leber congenital amaurosis. Nat Genet. 2003;35:158–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhang T, Zhang N, Baehr W, Fu Y. Cone opsin determines the time course of cone photoreceptor degeneration in Leber congenital amaurosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:8879–8884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ozcan U, Yilmaz E, Ozcan L, et al. Chemical chaperones reduce ER stress and restore glucose homeostasis in a mouse model of type 2 diabetes. Science. 2006;313:1137–1140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. de Almeida SF, Picarote G, Fleming JV, Carmo-Fonseca M, Azevedo JE, de Sousa M. Chemical chaperones reduce endoplasmic reticulum stress and prevent mutant HFE aggregate formation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:27905–27912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gao X, Fu L, Xiao M, et al. The nephroprotective effect of tauroursodeoxycholic acid on ischaemia/reperfusion-induced acute kidney injury by inhibiting endoplasmic reticulum stress. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol In press [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22. Malo A, Krüger B, Seyhun E, et al. Tauroursodeoxycholic acid reduces endoplasmic reticulum stress, trypsin activation, and acinar cell apoptosis while increasing secretion in rat pancreatic acini. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2010;299:G877–G886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mantopoulos D, Murakami Y, Comander J, et al. Tauroursodeoxycholic acid (TUDCA) protects photoreceptors from cell death after experimental retinal detachment. PLoS One. 2011;6:e24245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Boatright JH, Moring AG, McElroy C, et al. Tool from ancient pharmacopoeia prevents vision loss. Mol Vis. 2006;12:1706–1714 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Phillips MJ, Walker TA, Choi H-Y, et al. Tauroursodeoxycholic acid preservation of photoreceptor structure and function in the rd10 mouse through postnatal day 30. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2008;49:2148–2155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Oveson BC, Iwase T, Hackett SF, et al. Constituents of bile, bilirubin and TUDCA, protect against oxidative stress-induced retinal degeneration. J Neurochem. 2011;116:144–153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Fernandez-Sanchez L, Lax P, Pinilla I, Martin-Nieto J, Cuenca N. Tauroursodeoxycholic acid prevents retinal degeneration in transgenic P23H rats. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:4998–5008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Drack AV, Dumitrescu AV, Bhattarai S, et al. TUDCA slows retinal degeneration in two different mouse models of retinitis pigmentosa and prevents obesity in Bardet-Biedl syndrome type 1 mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012;53:100–106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sola S, Castro RE, Laires PA, Steer CJ, Rodrigues CM. Tauroursodeoxycholic acid prevents amyloid-beta peptide-induced neuronal death via a phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase-dependent signaling pathway. Mol Med. 2003;9:226–234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Viana RJ, Nunes AF, Castro RE, et al. Tauroursodeoxycholic acid prevents E22Q Alzheimer's Abeta toxicity in human cerebral endothelial cells. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:1094–1104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ramalho RM, Viana RJS, Castro RE, et al. Apoptosis in transgenic mice expressing the P301L mutated form of human tau. Mol Med. 2008;14:309–317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ramalho RM, Viana RJ, Low WC, Steer CJ, Rodrigues CM. Bile acids and apoptosis modulation: an emerging role in experimental Alzheimer's disease. Trends Mol Med. 2008;14:54–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ramalho RM, Borralho PM, Castro RE, Solá S, Steer CJ, Rodrigues CM. Tauroursodeoxycholic acid modulates p53-mediated apoptosis in Alzheimer's disease mutant neuroblastoma cells. J Neurochem. 2006;98:1610–1618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rodrigues CM, Solá S, Brito MA, Brondino CD, Brites D, Moura JJ. Amyloid beta-peptide disrupts mitochondrial membrane lipid and protein structure: protective role of tauroursodeoxycholate. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;281:468–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Duan WM, Rodrigues CM, Zhao LR, Steer CJ, Low WC. Tauroursodeoxycholic acid improves the survival and function of nigral transplants in a rat model of Parkinson's disease. Cell Transplant. 2002;11:195–205 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Boatright JH, Nickerson JM, Moring AG, Pardue MT. Bile acids in treatment of ocular disease. J Ocul Biol Dis Infor 2:149–159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Fu Y, Kefalov V, Luo DG, Xue T, Yau KW. Quantal noise from human red cone pigment. Nat Neurosci 11:565–571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Shi G, Yau KW, Chen J, Kefalov VJ. Signaling properties of a short-wave cone visual pigment and its role in phototransduction. J Neurosci. 2007;27:10084–10093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhu X, Li A, Brown B, Weiss ER, Osawa S, Craft CM. Mouse cone arrestin expression pattern: light induced translocation in cone photoreceptors. Mol Vis. 2002;8:462–471 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yoshida H. ER stress and diseases. Febs J. 2007;274:630–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Sato K, Nakazawa M, Takeuchi K, Mizukoshi S, Ishiguro S. S-opsin protein is incompletely modified during N-glycan processing in Rpe65(−/−) mice. Exp Eye Res. 2010;91:54–62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Lilley BN, Ploegh HL. A membrane protein required for dislocation of misfolded proteins from the ER. Nature. 2004;429:834–840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ye Y, Shibata Y, Yun C, Ron D, Rapoport TA. A membrane protein complex mediates retro-translocation from the ER lumen into the cytosol. Nature. 2004;429:841–847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Bernasconi R, Molinari M. ERAD. and ERAD tuning: disposal of cargo and of ERAD regulators from the mammalian ER. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2011;23:176–183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Smith MH, Ploegh HL, Weissman JS. Road to ruin: targeting proteins for degradation in the endoplasmic reticulum. Science. 2011;334:1086–1090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Amaral JD, Viana RJ, Ramalho RM, Steer CJ, Rodrigues CM. Bile acids: regulation of apoptosis by ursodeoxycholic acid. J Lipid Res. 2009;50:1721–1734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Conn PM, Ulloa-Aguirre A. Pharmacological chaperones for misfolded gonadotropin-releasing hormone receptors. Adv Pharmacol. 2011;62:109–141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ulloa-Aguirre A, Janovick JA, Brothers SP, Conn PM. Pharmacologic rescue of conformationally-defective proteins: implications for the treatment of human disease. Traffic 5:821–837 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bainbridge JW, Smith AJ, Barker SS, et al. Effect of gene therapy on visual function in Leber's congenital amaurosis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2231–2239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Maguire AM, Simonelli F, Pierce EA, et al. Safety and efficacy of gene transfer for Leber's congenital amaurosis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:2240–2248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Hauswirth WW, Aleman TS, Kaushal S, et al. Treatment of leber congenital amaurosis due to RPE65 mutations by ocular subretinal injection of adeno-associated virus gene vector: short-term results of a phase I trial. Hum Gene Ther. 2008;19:979–990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Cideciyan AV, Aleman TS, Boye SL, et al. Human gene therapy for RPE65 isomerase deficiency activates the retinoid cycle of vision but with slow rod kinetics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:15112–15117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Maguire AM, High KA, Auricchio A, et al. Age-dependent effects of RPE65 gene therapy for Leber's congenital amaurosis: a phase 1 dose-escalation trial. Lancet. 2009;374:1597–1605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Jacobson SG, Cideciyan AV, Ratnakaram R, et al. Gene therapy for leber congenital amaurosis caused by RPE65 mutations: safety and efficacy in 15 children and adults followed up to 3 years. Arch Ophthalmol. 2012;130:9–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Cronin T, Leveillard T, Sahel JA. Retinal degenerations: from cell signaling to cell therapy; pre-clinical and clinical issues. Curr Gene Ther. 2007;7:121–129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Van Hooser JP, Aleman TS, He YG, et al. Rapid restoration of visual pigment and function with oral retinoid in a mouse model of childhood blindness. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:8623–8628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Ablonczy Z, Crouch RK, Goletz PW, et al. 11-cis-retinal reduces constitutive opsin phosphorylation and improves quantum catch in retinoid-deficient mouse rod photoreceptors. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:40491–40498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Koenekoop RK, Racine J, Humaid SA, et al. Oral synthetic cis-retinoid therapy in subjects with Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA) due to lecithin: retinol acyltransferase (LRAT) or retinal pigment epithelial 65 protein (RPE65) mutations: preliminary results of a phase Ib open label trial. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:3323 [Google Scholar]

- 59. Fan J, Crouch RK, Kono M. Light prevents exogenous 11-cis retinal from maintaining cone photoreceptors in chromophore-deficient mice. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:2412–2416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Poupon RE, Bonnand AM, Chretien Y, Poupon R. Ten-year survival in ursodeoxycholic acid-treated patients with primary biliary cirrhosis. The UDCA-PBC Study Group. Hepatology. 1999;29:1668–1671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kaplan MM, Gershwin ME. Primary biliary cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1261–1273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]