Abstract

Autoreactive pathogenic T cells (Tpaths) and regulatory T cells (Tregs) express a distinct gene profiles; however, the genes and associated genetic/signaling pathways responsible for the functional determination of Tpaths vs. Tregs remain unknown. Here we show that Skp2, an E3 ubiquitin ligase that affects cell cycle control and death, plays a critical role in the function of diabetogenic Tpaths and Tregs. Down-regulation of Skp2 in diabetogenic Tpaths converts them into Foxp3-expressing Tregs. The suppressive function of the Tpath-converted Tregs is dependent on increased production of TGF-β/IL-10, and these Tregs are able to inhibit spontaneous diabetes in NOD mice. Like naturally arising Foxp3+ nTregs, the converted Tregs are anergic cells with decreased proliferation and activation-induced cell death. Skp2 down-regulation leads to Tpath–Treg conversion due at least in part to up-regulation of several genes involved in cell cycle control and genes in the Foxo family. Down-regulation of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27 alone significantly attenuates the effect of Skp2 on Tpaths and reduces the suppressive function of converted Tregs; its effect is further improved with concomitant down-regulation of p21, Foxo1, and Foxo3. In comparison, Skp2 overexpression does not change Tpath function, but significantly decreases Foxp3 expression and abrogates the suppressive function of nTregs. These findings support the critical role of Skp2 in functional specification of Tpaths and Tregs, and demonstrate an important molecular mechanism mediating Skp2 function in balancing immune tolerance during autoimmune disease development.

Keywords: type 1 diabetes, autoimmunity, autoreactive cells

Autoreactive pathogenic T cells (Tpaths) play a critical role in the development of autoimmune diseases, including type 1 diabetes (T1D) (1, 2). Regulatory T cells (Tregs), including naturally-arising Foxp3+ nTregs and induced Treg-like IL-10–dependent Tregs, are known to play a critical role in maintaining immune tolerance to prevent Tpath-mediated autoimmune diseases (3–6). Deficiency in Tregs due to either abnormal development or experimental depletion leads to multiorgan autoimmune disorders and immunopathology (7–9). Therefore, maintaining well-balanced Tpath and Treg populations is important to immune function. Understanding the genetic and signaling mechanisms controlling the functional determination of these T cells should help maintain immune tolerance and suppression of self-tissue destruction by Tpaths. Comparative gene array analyses have shown that autoreactive Tpaths and Tregs express a distinct gene profile (10). The genes responsible for the functional determination of Tpaths vs. Tregs remain unclear, however.

The F-box protein S-phase kinase-associated protein 2 (Skp2) is an oncogene and a critical component of the SCFSkp2 ubiquitin ligase complex, comprising three invariable core subunits: Rbx1, Cul1, and Skp1. Skp2 is the E3 ubiquitin ligase unit responsible for the timely degradation of several proteins, including p21, p27KIP1, p57, and p130, which can negatively regulate the cell division cycle (11–18). Recent studies have demonstrated that Skp2-KO mice are viable and do not have an increased incidence of cancer (19). On the other hand, increased expression of Skp2 has been observed during the proliferation of T leukemia cells and T lymphoma cells, leading to Skp2-mediated tumor suppressor ubiquitylation and increased cell cycling activity (20, 21). Beyond these effects, the role of Skp2 in T cells, particularly its role in regulating the function of Tpaths and Tregs, remains unknown.

Results from our preliminary studies and other studies have shown that Skp2 and Foxp3 are expressed reciprocally in CD4+Foxp3− T cells vs. CD4+Foxp3+ nTregs and in human breast cancer cells (22). Based on these findings, we hypothesized that Skp2 might play an important role in regulating the function of autoreactive Tpaths vs. Tregs during the pathogenesis and development of T1D. Here we report the results from studies addressing this hypothesis and demonstrate that Skp2 down-regulation reprograms and converts diabetogenic Tpaths to potent Foxp3+ Tregs at least in part through regulation of cell cycle control genes and Foxo family genes. In contrast, overexpression of Skp2 in Foxp3+ nTregs attenuates Foxp3 expression and abolishes their suppressive function. Thus, our results support the conclusion that Skp2 can act as an important molecular and functional switch between Tpaths and Tregs.

Results and Discussion

Our previous genome-wide gene expression analyses established that autoreactive Tpaths and Tregs display distinct gene expression profiles (10). In addition, Skp2 and Foxp3 (a known critical regulator of Treg function) are inversely expressed in CD4+Foxp3− T cells and CD4+Foxp3+ nTregs (Fig. 1A), as well as some cancer cells (22). Skp2 is expressed at a much higher level (>40-fold) in Foxp3− T cells than in Foxp3+ Tregs. We also found that Skp2 was highly expressed in the diabetogenic CD4+Foxp3− BDC2.5 (BDC) cells (Fig. S1A), which are Tpaths that cause aggressive T1D in NOD mice (1, 2, 23). To determine whether Skp2 plays an important role in regulating the function of autoreactive Tpaths vs. Tregs during pathogenesis of T1D, we used a gene-specific shRNA to down-regulate ∼90% of Skp2 expression in BDC cells (Fig. S1 B and C). Skp2 down-regulation led to a concomitant large increase in Foxp3 expression (∼17-fold in mRNA and ∼8-fold in protein) in BDC cells (BDC-shSkp2) compared with WT BDC cells (BDC) and BDC cells expressing a control scrambled shRNA (BDC-Scrm) (Fig. S1 D and E).

Fig. 1.

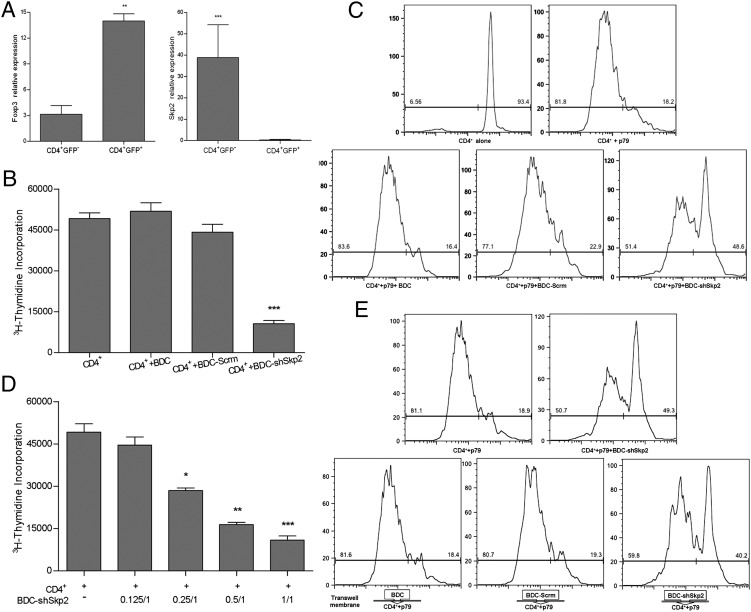

BDC cells acquired potent suppressive function in vitro after Skp2 knockdown. (A) Inverse expression of Foxp3 and Skp2 in CD4+GFP+ Tregs and CD4+GFP− non-Tregs analyzed by real-time PCR. CD4+Foxp3+ Tregs were GFP+ cells purified from Foxp3/GFP reporter NOD mice (36). Results shown are the gene expression levels relative to that of the endogenous β-actin gene. Data are mean ± SD. n > 3, with each experiment run in triplicate. **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.005. (B and C) BDC-shSkp2 cells, but not control cells, were able to suppress proliferation of 3H-thymidine-labeled (B) or CFSE-labeled (C) CD4+ target T cells in response to activation by p79 plus APCs. Data in B are mean ± SD from at least three measurements, each in triplicate. ***P < 0.005. In C, representative results of three independent experiments are shown. (D) Suppression of CD4+ target T cells with BDC-shSkp2 cells at various Treg/target cell ratios. Data are mean ± SD from at least three measurements, each in triplicate. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.005. (E) Suppressive function assays in transwells in which target cells and Tregs were physically separated. Representative results of three independent experiments are shown.

To examine the effect of Skp2 down-regulation on the function of BDC cells, we evaluated whether Tregs were still able to suppress BDC-shSkp2 cells. Compared with BDC or BDC-Scrm control cells, BDC-shSkp2 cells were ∼3.2-fold more resistant to Treg suppression (Fig. S2). We then determined whether the Foxp3+ BDC-shSkp2 cells function as Tregs. In two different suppression assays (Fig. 1 B and C), BDC-shSkp2 cells, but not the control cells, were able to suppress ∼80% of the proliferation of CD4+ target cells. Moreover, BDC-shSkp2 cells retained ∼40% of their suppressive effect on target cells at a 0.25:1 Treg:target ratio (Fig. 1D). These findings indicate that the BDC cells acquired potent suppressive function in vitro and, by this definition, were converted to Tregs after Skp2 knockdown.

We next determined whether, like Foxp3+ nTregs (3, 5, 7, 8), BDC-shSkp2 cells could function dependent on direct contact with target cells. BDC-shSkp2, BDC, and BDC-Scrm cells were cultured in transwells so they were physically separated from target cells. In the absence of direct cell contact, BDC-shSkp2 cells were only slightly (∼20%) less effective in suppressing target cell proliferation than the controls (Fig. 1E). These data indicate that cell contact plays a minor role, and that soluble factors likely play a more important role in mediating BDC-shSkp2 Treg function.

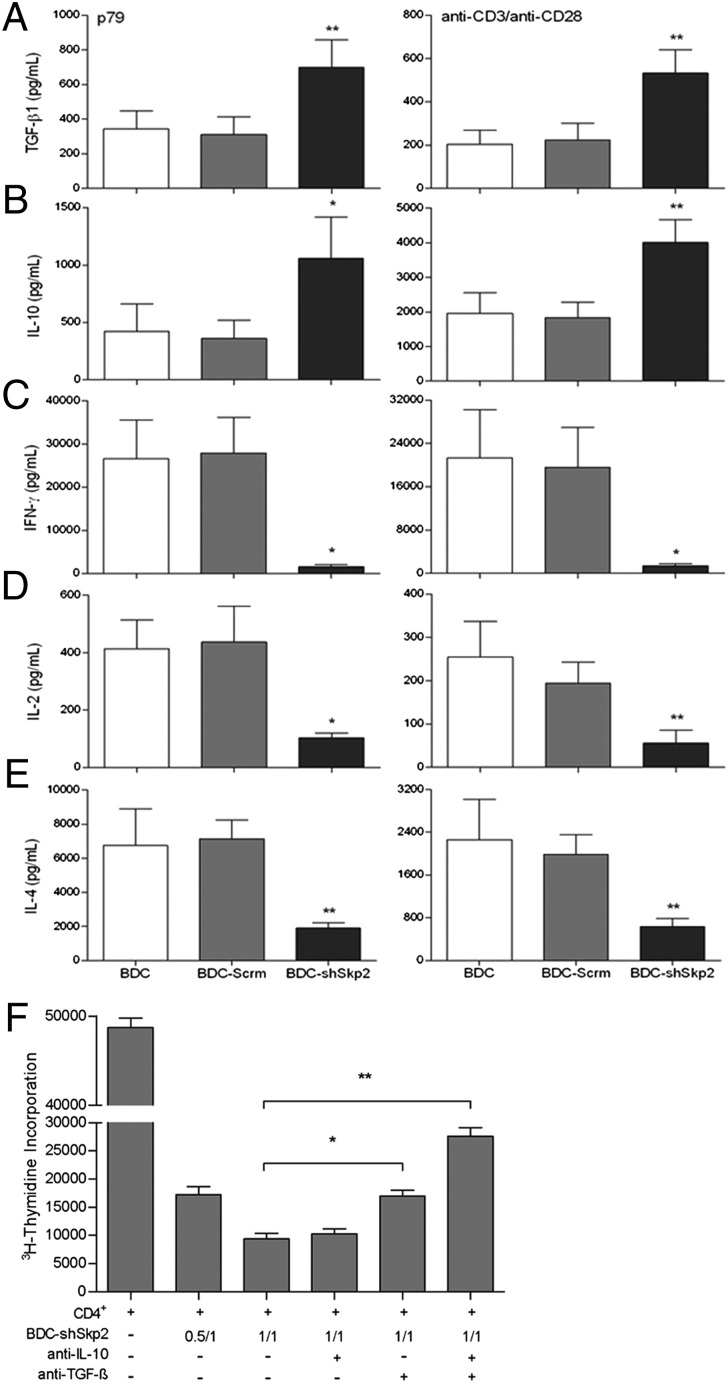

We used ELISA to identify the soluble factors that may contribute to the BDC-shSkp2 Treg function. Compared with control cells, BDC-shSkp2 cells produced significantly more TGF-β and IL-10 but much less IFN-γ, IL-2, and IL-4 in response to stimulation by either peptide or anti-CD3/CD28 (Fig. 2 A–E). We then performed cytokine blockade assays to investigate whether the function of BDC-shSkp2 Tregs was dependent on TGF-β and/or IL-10. Anti–TGF-β, but not anti–IL-10, alone significantly reduced the suppressive function of BDC-shSkp2 Tregs and increased target cell proliferation by approximately twofold (Fig. 2F). The blockade effect of anti–TGF-β was further enhanced in combination with anti–IL-10, leading to an ∼threefold increase in target cell proliferation. Therefore, although other soluble factors might be involved, TGF-β can synergize with IL-10 in mediating the regulatory function of BDC-shSkp2 Tregs.

Fig. 2.

Down-regulation of Skp2 led to significantly increased TGF-β and IL-10 production by BDC-shSkp2 cells. (A–E) BDC-shSkp2 cells and control cells were activated with either p79 plus irradiated APCs or anti-CD3/CD28 antibodies for 24 h. Cell culture supernatant was harvested for ELISA of TGF-β (A), IL-10 (B), IFN-γ (C), IL-2 (D), or IL-4 (E). Data are mean ± SD from at least three measurements, each in triplicate. (F) Blockade of BDC-shSkp2 cells’ suppressive function by anti–TGF-β and anti–IL-10. Data are mean ± SD from at least three measurements, each in triplicate.

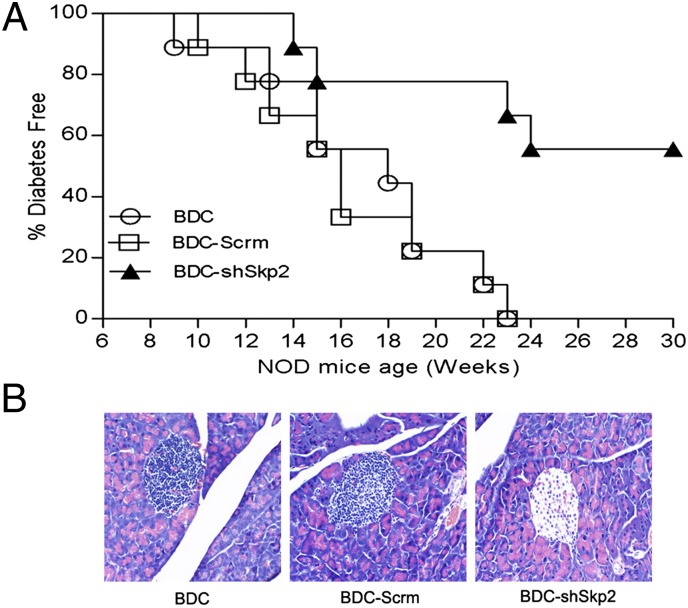

Foxp3+ Tregs are known to play a critical role in preventing T1D (23–25). We thus examined whether BDC-shSkp2 Tregs are able to inhibit spontaneous T1D by adoptively transferring the cells into 6-wk-old NOD mice. Compared with control cell-transferred mice, onset of T1D was delayed by 4 wk in NOD mice transferred with BDC-shSkp2 cells (Fig. 3A). More importantly, although all control NOD mice developed T1D by age 23 wk, only 45% of BDC-shSkp2 cell-transferred mice developed T1D. In addition, BDC-shSkp2 cells, but not control cells, prevented insulitis in recipient mice (Fig. 3B). Taken together, these results support the conclusion that Skp2–down-regulated BDC cells are converted to potent Tregs that are able to inhibit insulitis and spontaneous T1D in NOD mice.

Fig. 3.

BDC-shSkp2 cells were able to inhibit spontaneous T1D in NOD mice. (A) BDC-shSkp2 cells can inhibit spontaneous T1D in NOD recipient mice. Six-wk-old female NOD mice received a single i.v. injection of 1 × 107 BDC, BDC-Scrm, or BDC-shSkp2 cells. Recipient mice were monitored for up to age 30 wk and were considered diabetic after 2 consecutive weeks of glycosuria ≥2% and blood glucose level ≥250 mg/dL. (B) Histological analyses of pancreatic sections from 23-wk-old NOD recipient mice. Images are representative of sections from at least three mice per group.

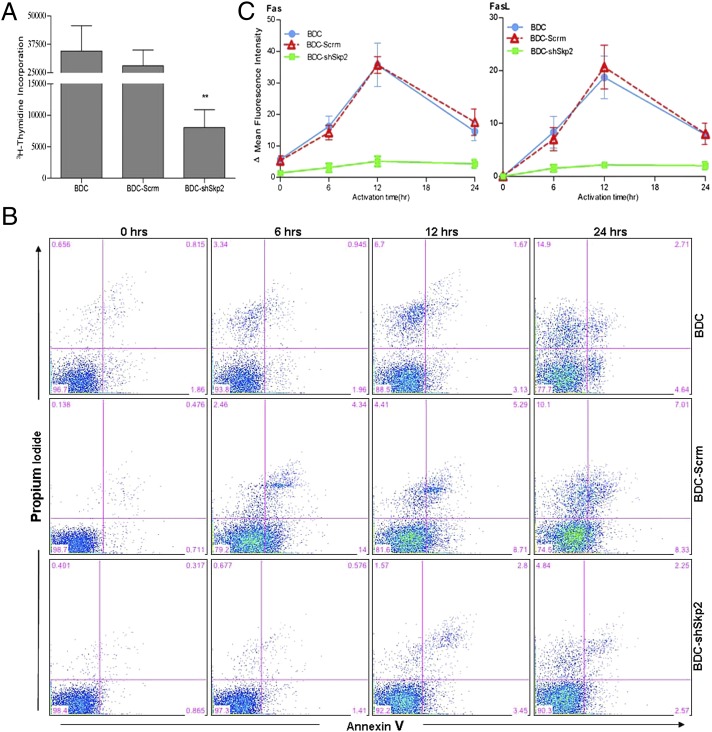

Because Skp2 is a key regulator of cell cycle control, we examined whether its down-regulation can affect BDC cell proliferation in vitro. We found decreased BDC-shSkp2 cell proliferation in response to anti-CD3/CD28 stimulation, ∼3.5- to 4-fold lower than that in control cells (Fig. 4A). These results indicate that, like Foxp3+ nTregs, BDC-shSkp2 Tregs are anergic cells. nTregs are known to be less sensitive than T effector cells to activation-induced cell death (AICD) (26). To determine whether this is also the case for BDC-shSkp2 Tregs, we activated the cells using either anti-TCR/CD28 (Fig. 4B) or anti-CD3/CD28 (Fig. S3). Our findings indicate that activation of the control cells triggered time-dependent AICD; however, as expected, BDC-shSkp2 cells were more refractory to AICD.

Fig. 4.

Skp2 knockdown in BDC cells decreases cell proliferation and activation-induced cell death. (A) BDC-shSkp2 cells and control cells were activated with anti-CD3/CD28, and their proliferation was measured in a 4-d assay. Data are mean ± SD from at least three measurements, each in triplicate. (B) Indicated cells either untreated (0 h) or treated with anti-TCR/CD28 were cultured for 6, 12, and 24 h. Cell death was measured by annexin V and propidium iodide staining. Similar results were obtained from three independent experiments. (C) Surface expression of Fas or FasL after activation for 6, 12, and 24 h by anti-TCR/CD28. Data are mean ± SD from at least three measurements, each in triplicate.

Fas–Fas ligand (FasL) interaction represents a major cell death pathway for T cells (27). We investigated whether Skp2 down-regulation may prevent AICD of BDC-shSkp2 cells through control of the Fas/FasL pathway, and found that Fas/FasL expression on BDC or BDC-Scrm cells was highest at 12 h after activation and decreased thereafter (Fig. 4C). However, compared with controls, BDC-shSkp2 cells not only expressed lower basal levels of Fas/FasL, but also exhibited only slightly increased Fas/FasL expression after activation. These findings further support the conclusion that Skp2 down-regulation negatively regulates both the proliferation and the AICD of BDC cells, a phenotype reminiscent of Foxp3+ nTregs.

To better understand the molecular mechanisms of how Skp2 may affect BDC cell function, we performed preliminary RNA microarray analyses and found up-regulation of ∼680 genes and down-regulation of ∼1,190 genes in BDC-shSkp2 cells, compared with that in BDC-Scrm cells. We then chose several genes for validation by real-time PCR (Fig. 5A and Fig. S4 A and B). Compared with controls, Skp2 down-regulation increased the transcription of several cell cycle suppressor genes, including p16, p27, p57, and p130, but decreased the transcription of p21 (Fig. 5A). The expression of Foxo1 and Foxo3, which play critical roles in regulating Foxp3 expression and Treg development (28–30), was increased as well (Fig. 5A). Moreover, Skp2 knockdown significantly up-regulated expression of Cul-1 and Skp1, essential components of the Cul1–Rbx1–Skp1–F boxSkp2 ubiquitin ligase complex (11–15, 18) (Fig. S4B). In contrast, transcription of cell cycle-promoting regulator genes (including cyclin E and c-Myc) was down-regulated (Fig. S4A). Western blot analyses validated the findings at the protein level (Fig. 5B and Figs. S4C and S5) for all except p21, cyclin E, and c-Myc. In contrast to their reduced mRNA levels, protein levels of p21, cyclin E, and c-Myc were increased in BDC-shSkp2 cells.

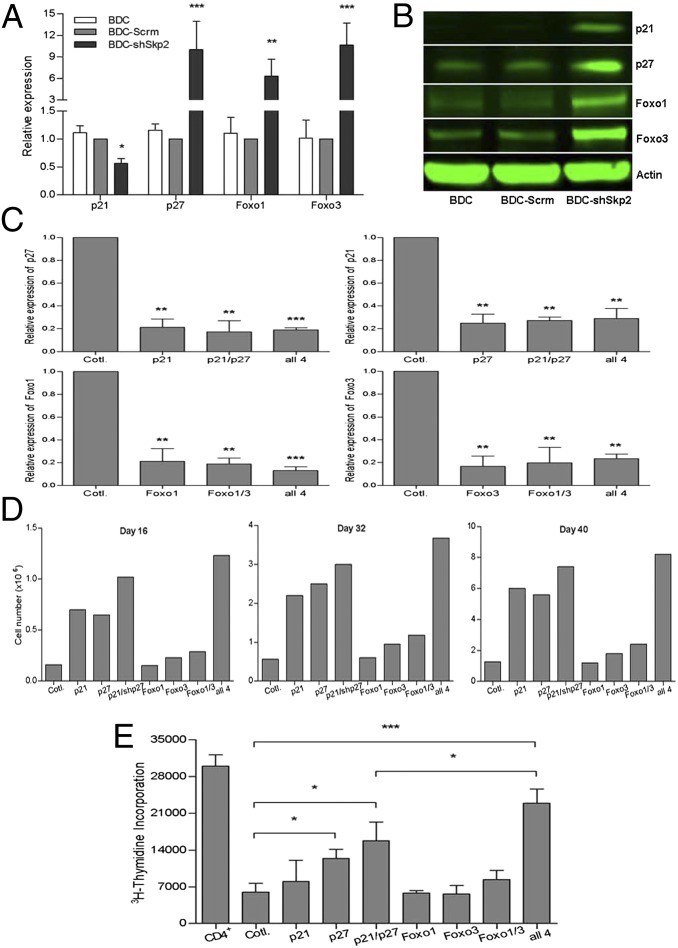

Fig. 5.

Inhibition of p21, p27, Foxo1, and Foxo3 expression restored cell proliferation and abolished suppressive function of BDC-shSkp2 cells.(A) Expression of indicated genes in BDC-shSkp2 cells and control cells. Results shown are the gene expression levels relative to that of the endogenous β-actin gene, normalized to the results from the BDC-Scrm cells. Data are mean ± SD from at least three measurements, each in triplicate. (B) Western blot analyses of indicated protein expression in BDC-shSkp2 cells and control cells. (C) Expression of shRNAs against p21, p27, Foxo1, or Foxo3 either alone or in various combinations reduced their expression by ∼80% in BDC-shSkp2 cells. Results shown are expression levels of the indicated genes relative to that of the β-actin gene, normalized to their expression in BDC-shSkp2 cells expressing scrambled shRNA. Data are mean ± SD from at least three measurements each in triplicate. (D) Proliferation of BDC-shSkp2 cells was restored to varying degrees after reduced expression of p21, p27, Foxo1, and/or Foxo3. Cell proliferation was determined by trypan blue staining at 16, 32, and 40 d after cell culture. Data are means from two independent measurements, each in triplicate. (E) The suppressive function of BDC-shSkp2 cells was blocked to varying degrees after reduced expression of p21, p27, Foxo1, and/or Foxo3. Data are mean ± SD from at least three measurements, each in triplicate.

We next examined whether molecules with elevated protein levels in BDC-shSkp2 cells are responsible for mediating the effects of Skp2 on BDC cells. Along with their roles in regulating Foxp3 expression and Treg function (28–30), Foxo1 and Foxo3 also regulate p21 and p27 expression (31–33). In addition, degradation of Foxo1/Foxo3 and/or p21/p27 by Skp2 plays an important role in increased cell division (11, 12, 34, 35). Given the increased expression of p21, p27, Foxo1, and Foxo3 in BDC-shSkp2 cells, we hypothesized that Skp2 may control BDC cell phenotype and function through these protein factors.

To address this hypothesis, we investigated whether down-regulation of these factors blocked the effect of Skp2-down-regulation on BDC cells. Expression of shRNAs against p21, p27, Foxo1, and Foxo3, either alone or in various combinations, reduced the expression of these genes in BDC-shSKP2 cells by ∼80% (Fig. 5C). If these genes do in fact contribute to the effect of Skp2 on BDC cells, then restoration of the proliferation of treated BDC-shSkp2 cells and abrogation of their suppressive function would be expected. Indeed, down-regulation of p21 or p27 alone significantly rescued cell growth arrest of BDC-shSkp2 cells, and expression of shRNAs against both p21/p27 showed a stronger reversal effect (Fig. 5D). Importantly, the suppressive function of the converted BDC-shSkp2 Tregs was significantly abolished by shRNA against p27, and the reversal effect was further enhanced by shRNAs against both p21 and p27, although p21 alone had no effect (Fig. 5E).

Knockdown of Foxo3, either alone or together with Foxo1 in BDC-shSkp2 cells, produced only slight increases in cell growth and reductions in cell suppressive function, and knockdown of Foxo1 alone had no effect (Fig. 5 D and E). However, compared with BDC-shSkp2 cells expressing shRNAs against both p21 and p27, concomitant down-regulation of all four genes (Foxo1, Foxo3, p21, and p27) further restored cell proliferation and blocked suppressive function (Fig. 5 D and E). These findings indicate that down-regulation of Skp2 can control BDC cell growth and functional determination through modulation of p27 expression. The other genes, including p21, Foxo1, and Foxo3, may synergize with p27 in mediating the regulatory effect of Skp2 on the phenotype and function of Tpaths like BDC cells.

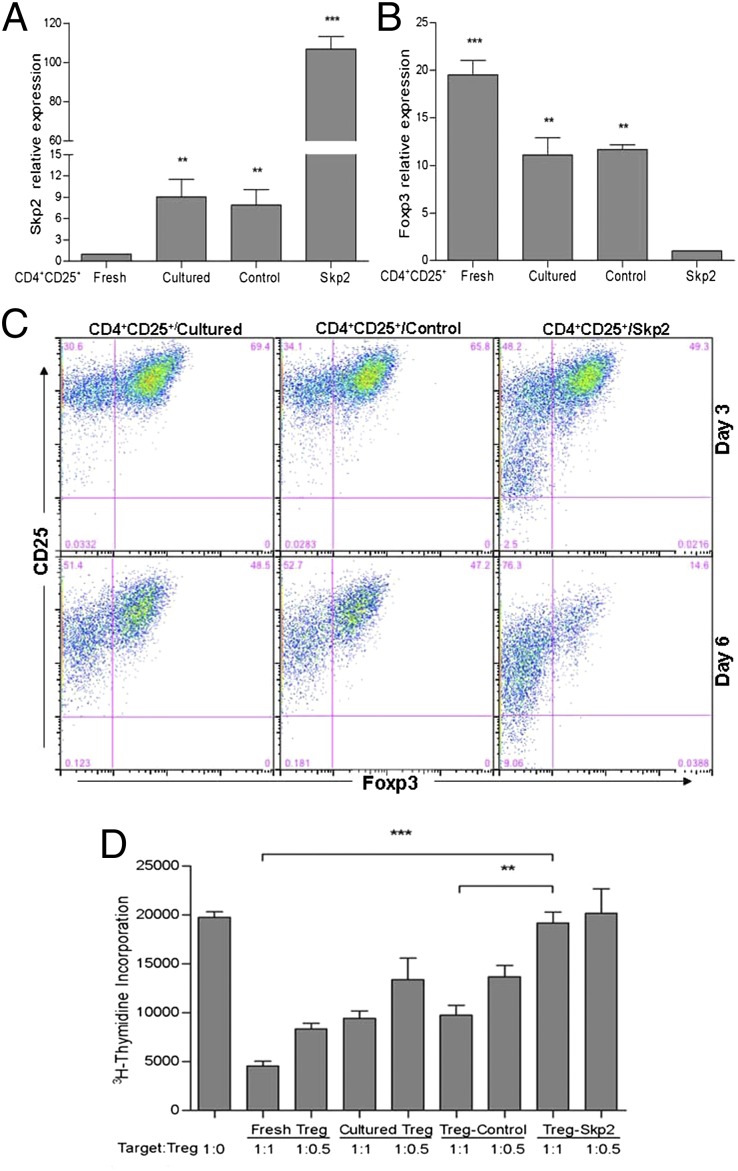

To further understand the role of Skp2 in regulating function of Tpaths vs. Tregs, we also examined the effect of Skp2 overexpression on BDC cells. We found that, as expected, Skp2 overexpression did not convert BDC cells to suppressive cells (Fig. S6 A–C). Because Skp2 and Foxp3 show inverse expression in nTregs (Fig. 1A), we examined whether Skp2 overexpression might affect the function of nTregs isolated from NOD mice. We found that overexpression of Skp2 in nTregs (Skp2 cells) resulted in an ∼13-fold increase in Skp2 expression and an ∼10-fold decrease in Foxp3 expression compared with nTregs expressing a control vector (control cells) or cultured untreated nTregs (cultured cells) (Fig. 6 A and B). The negative effect of Skp2 on Foxp3 was further demonstrated by intracellular staining of Foxp3 (Fig. 6C). In general, Foxp3 expression was decreased in CD4+CD25+ nTregs with increased culture time (Fig. 6C); however, Skp2-overexpressing CD4+CD25+/Skp2 cells lost Foxp3 expression much faster than controls. Foxp3 expression decreased rapidly, from 80% to 85% on day 0 to ∼50% on day 3 and ∼15% on day 6, in CD4+CD25+/Skp2 cells after cell culture in vitro (Fig. 6C). In comparison, the control cells (CD4+CD25+/cultured and CD4+CD25+/control cells) still contained 65–70% Foxp3+ cells on day 3 and 47–50% on day 6. Importantly, Foxp3 reduction in CD4+CD25+/Skp2 cells was accompanied by a complete loss of suppressive function (Fig. 6D). These results provide additional information on the role of Skp2 in regulating Treg function that complements the findings from studies on the effect of Skp2 in converting BDC cells to Foxp3+ Tregs.

Fig. 6.

Overexpression of Skp2 in CD4+CD25+ nTregs led to decreased expression of Foxp3 and loss of regulatory function. (A and B) Expression of Skp2 and Foxp3 on day 6 after cell culture was determined by real-time PCR in freshly isolated (fresh) or cultured (cultured) CD4+CD25+ nTregs or in cultured nTregs expressing an empty control vector (control) or a vector containing Skp2 cDNA (Skp2). Results shown are expression levels of Skp2 or Foxp3 relative to β-actin gene expression, normalized to those in freshly isolated nTregs (A) or Skp2-overexpressing nTreg/Skp2 cells (B). Data are mean ± SD from at least three measurements, each in triplicate. (C) Overexpression of Skp2 led to faster loss of Foxp3+ cells in CD4+CD25+/Skp2 cells than in CD4+CD25+/cultured and CD4+CD25+/control cells on day 3 and day 6 after cell culture. Results shown are representative of three independent experiments. (D) Overexpression of Skp2 abolished the function of nTregs in suppressing CD4+CD25− target cells. Data are mean ± SD from at least three measurements, each in triplicate.

The present study has demonstrated that Skp2 is a dynamic key regulator that acts as an important functional switch between Tpaths and Tregs. Therefore, proper control of Skp2 expression in these functionally distinct T cells likely is critical for inducing/maintaining immune tolerance in animals and humans. Several genes have been identified as either targets for Skp2 or potentially involved in mediating the effect of Skp2 on T cells. Among these candidates, the genes involved in cell cycle control probably play an important role in controlling the functional differentiation and/or maturation of Tpaths and Tregs during the development of autoimmune diseases. Identification of molecular and cellular mechanisms regulating the expression and function of Skp2 and its associated genes in Tpaths or Tregs would provide insight into ways to improve cell-based immunotherapy to prevent or treat autoimmune diseases like T1D.

Materials and Methods

Mice and Cells.

NOD mice were purchased from the Jackson Laboratory. BDC2.5 T-cell receptor (TCR) transgenic NOD (BDC) mice were a gift from Diane Mathis and Christopher Benoist (Joslin Diabetes Center, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA) (23). Foxp3/GFP reporter mice (36) were a gift from Vijay Kuchroo (Brigham and Women's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA). All animals were housed in a specific pathogen-free animal facility at the Beckman Research Institute, City of Hope. Approximately 80% of the female NOD mice developed diabetes by age 23 wk.

The 2D2 cells are Treg clones derived from the previously described N206 Treg line (37). BDC T cells were stimulated by the 1040–79 peptide (p79), a mimitope that is one of the most active peptides in stimulating BDC T cells, as described previously (38). CD4+ BDC cells isolated from BDC mice were activated three times by the p79 peptide in vitro and used as the Tpaths. These BDC cells did not express Foxp3 and were able to induce an aggressive form of T1D when transferred to NOD/SCID mice. CD4+CD25− and CD4+CD25+ T cells were isolated from NOD mouse splenocytes and purified by negative selection using magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec). Purified CD4+ T cells (mean purity, 95% ± 3%) were subsequently separated into CD25+ or CD25− T cells using anti-CD25 magnetic beads. The mean purity of bead-isolated CD4+CD25+ nTregs and CD4+CD25− target/responder T cells was 90% ± 2% and 89% ± 3%, respectively. Additional Materials and Methods can be found in Supplemental Information.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by funds from the American Diabetes Association, the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, and the H. L. Snyder Medical Foundation.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1207293109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Haskins K, McDuffie M. Acceleration of diabetes in young NOD mice with a CD4+ islet-specific T cell clone. Science. 1990;249:1433–1436. doi: 10.1126/science.2205920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Katz JD, Wang B, Haskins K, Benoist C, Mathis D. Following a diabetogenic T cell from genesis through pathogenesis. Cell. 1993;74:1089–1100. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90730-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sakaguchi S, Powrie F. Emerging challenges in regulatory T cell function and biology. Science. 2007;317:627–629. doi: 10.1126/science.1142331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vieira PL, et al. IL-10–secreting regulatory T cells do not express Foxp3 but have comparable regulatory function to naturally occurring CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2004;172:5986–5993. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.10.5986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Uhlig HH, et al. Characterization of Foxp3+CD4+CD25+ and IL-10–secreting CD4+CD25+ T cells during cure of colitis. J Immunol. 2006;177:5852–5860. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.5852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.You S, et al. Presence of diabetes-inhibiting, glutamic acid decarboxylase-specific, IL-10–dependent regulatory T cells in naive nonobese diabetic mice. J Immunol. 2004;173:6777–6785. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.11.6777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sakaguchi S. Naturally arising CD4+ regulatory T cells for immunologic self-tolerance and negative control of immune responses. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:531–562. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.21.120601.141122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shevach EM. Regulatory/suppressor T cells in health and disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:2721–2724. doi: 10.1002/art.20500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.O’Garra A, Vieira P. Regulatory T cells and mechanisms of immune system control. Nat Med. 2004;10:801–805. doi: 10.1038/nm0804-801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qin H, et al. Killer cell Ig-like receptor (KIR) 3DL1 down-regulation enhances inhibition of type 1 diabetes by autoantigen-specific regulatory T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:2016–2021. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019082108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carrano AC, Eytan E, Hershko A, Pagano M. SKP2 is required for ubiquitin-mediated degradation of the CDK inhibitor p27. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:193–199. doi: 10.1038/12013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yu ZK, Gervais JL, Zhang H. Human CUL-1 associates with the SKP1/SKP2 complex and regulates p21(CIP1/WAF1) and cyclin D proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:11324–11329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.19.11324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jackson PK, Eldridge AG. The SCF ubiquitin ligase: An extended look. Mol Cell. 2002;9:923–925. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00538-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Frescas D, Pagano M. Deregulated proteolysis by the F-box proteins SKP2 and β-TrCP: Tipping the scales of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2008;8:438–449. doi: 10.1038/nrc2396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lisztwan J, et al. Association of human CUL-1 and ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme CDC34 with the F-box protein p45(SKP2): Evidence for evolutionary conservation in the subunit composition of the CDC34–SCF pathway. EMBO J. 1998;17:368–383. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.2.368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kamura T, et al. Degradation of p57Kip2 mediated by SCFSkp2-dependent ubiquitylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:10231–10236. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1831009100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tedesco D, Lukas J, Reed SI. The pRb-related protein p130 is regulated by phosphorylation-dependent proteolysis via the protein-ubiquitin ligase SCF(Skp2) Genes Dev. 2002;16:2946–2957. doi: 10.1101/gad.1011202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lyapina SA, Correll CC, Kipreos ET, Deshaies RJ. Human CUL1 forms an evolutionarily conserved ubiquitin ligase complex (SCF) with SKP1 and an F-box protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:7451–7456. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.13.7451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nakayama K, et al. Targeted disruption of Skp2 results in accumulation of cyclin E and p27(Kip1), polyploidy and centrosome overduplication. EMBO J. 2000;19:2069–2081. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.9.2069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kang-Decker N, et al. Loss of CBP causes T cell lymphomagenesis in synergy with p27Kip1 insufficiency. Cancer Cell. 2004;5:177–189. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(04)00022-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Latres E, et al. Role of the F-box protein Skp2 in lymphomagenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:2515–2520. doi: 10.1073/pnas.041475098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zuo T, et al. FOXP3 is a novel transcriptional repressor for the breast cancer oncogene SKP2. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3765–3773. doi: 10.1172/JCI32538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee MH, Lee WH, Todorov I, Liu CP. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells prevent type 1 diabetes preceded by dendritic cell-dominant invasive insulitis by affecting chemotaxis and local invasiveness of dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2010;185:2493–2501. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1001036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herman AE, Freeman GJ, Mathis D, Benoist C. CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells dependent on ICOS promote regulation of effector cells in the prediabetic lesion. J Exp Med. 2004;199:1479–1489. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pop SM, Wong CP, Culton DA, Clarke SH, Tisch R. Single cell analysis shows decreasing FoxP3 and TGFβ1 coexpressing CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells during autoimmune diabetes. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1333–1346. doi: 10.1084/jem.20042398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fritzsching B, et al. In contrast to effector T cells, CD4+CD25+FoxP3+ regulatory T cells are highly susceptible to CD95 ligand- but not to TCR-mediated cell death. J Immunol. 2005;175:32–36. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krammer PH. CD95’s deadly mission in the immune system. Nature. 2000;407:789–795. doi: 10.1038/35037728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kerdiles YM, et al. Foxo transcription factors control regulatory T cell development and function. Immunity. 2010;33:890–904. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ouyang W, et al. Foxo proteins cooperatively control the differentiation of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:618–627. doi: 10.1038/ni.1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ouyang W, Beckett O, Flavell RA, Li MO. An essential role of the Forkhead-box transcription factor Foxo1 in control of T cell homeostasis and tolerance. Immunity. 2009;30:358–371. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Medema RH, Kops GJ, Bos JL, Burgering BM. AFX-like Forkhead transcription factors mediate cell-cycle regulation by Ras and PKB through p27kip1. Nature. 2000;404:782–787. doi: 10.1038/35008115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Seoane J, Le HV, Shen L, Anderson SA, Massagué J. Integration of Smad and forkhead pathways in the control of neuroepithelial and glioblastoma cell proliferation. Cell. 2004;117:211–223. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00298-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tran H, Brunet A, Griffith EC, Greenberg ME. The many forks in FOXO’s road. Sci STKE. 2003;2003:RE5. doi: 10.1126/stke.2003.172.re5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cardozo T, Pagano M. The SCF ubiquitin ligase: Insights into a molecular machine. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:739–751. doi: 10.1038/nrm1471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang H, et al. Skp2 inhibits FOXO1 in tumor suppression through ubiquitin-mediated degradation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:1649–1654. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406789102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Korn T, et al. Myelin-specific re\gulatory T cells accumulate in the CNS but fail to control autoimmune inflammation. Nat Med. 2007;13:423–431. doi: 10.1038/nm1564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen C, Lee WH, Yun P, Snow P, Liu CP. Induction of autoantigen-specific Th2 and Tr1 regulatory T cells and modulation of autoimmune diabetes. J Immunol. 2003;171:733–744. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.2.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.You S, et al. Detection and characterization of T cells specific for BDC2.5 T cell-stimulating peptides. J Immunol. 2003;170:4011–4020. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.8.4011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen C, Lee WH, Zhong L, Liu CP. Regulatory T cells can mediate their function through the stimulation of APCs to produce immunosuppressive nitric oxide. J Immunol. 2006;176:3449–3460. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.6.3449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen C, Liu CP. Regulatory function of a novel population of mouse autoantigen-specific Foxp3 regulatory T cells depends on IFN-γ, NO, and contact with target cells. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e7863. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ortiz S, et al. Comparative analyses of differentially induced T-cell receptor-mediated phosphorylation pathways in T lymphoma cells. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2010;235:1450–1463. doi: 10.1258/ebm.2010.010056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.