Abstract

Microvascular networks support metabolic activity and define microenvironmental conditions within tissues in health and pathology. Recapitulation of functional microvascular structures in vitro could provide a platform for the study of complex vascular phenomena, including angiogenesis and thrombosis. We have engineered living microvascular networks in three-dimensional tissue scaffolds and demonstrated their biofunctionality in vitro. We describe the lithographic technique used to form endothelialized microfluidic vessels within a native collagen matrix; we characterize the morphology, mass transfer processes, and long-term stability of the endothelium; we elucidate the angiogenic activities of the endothelia and differential interactions with perivascular cells seeded in the collagen bulk; and we demonstrate the nonthrombotic nature of the vascular endothelium and its transition to a prothrombotic state during an inflammatory response. The success of these microvascular networks in recapitulating these phenomena points to the broad potential of this platform for the study of cardiovascular biology and pathophysiology.

Keywords: tissue engineering, regenerative medicine, microfluidics, cancer, blood

The microvasculature is an extensive organ that mediates the interaction between blood and tissues. It defines the biological and physical characteristics of the microenvironment within tissues and plays a role in the initiation and progression of many pathologies, including cancer (1) and cardiovascular diseases (2, 3). Conventional planar cultures fail to recreate the in vivo physiology of the microvasculature with respect to three-dimensional (3D) geometry (lumens and axial branching points), and interactions of endothelium with perivascular cells, extracellular tissue and blood flow (4). Studies of the microvasculature in vivo allow only limited control of physical, chemical, and biological parameters influencing the microvasculature and present challenges with respect to observation (5). In vitro cultures that produce tubular vessels within 3D matrices will aid in elucidation of the roles of the microvasculature in health and disease. Important progress has been made toward this goal: Biologically derived or synthetic materials have been used to generate macrovessel tubes (6) and endothelialized microtubes (7); cellular self-assembly has been used to generate random microvasculature (8); microfabrication has been used to define complex geometries in hydrogels at the micro-scale (9); and distributions of cells and biochemical factors within 3D scaffolds (10). Of particular note, the group of Tien has pioneered the use of collagen to template the growth of vascular endothelium (7, 11) and demonstrated appropriate permeability (7), response to cyclic AMP (12), and differential properties as a function of the luminal shear stress and composition of the medium (13). Nonetheless, prior methodologies have been unable to produce endothelialized networks that can undergo substantial remodeling via angiogenesis; elucidate the roles of perivascular cells in modulating vascular morphology and permeability; control cellular, chemical, and physical stimuli at microscale levels to manipulate the interactions between different cell types and their matrices; and produce vessels with normal antithrombotic function when quiescent and prothrombotic behavior when exposed to inflammatory stimuli.

Here, we address these challenges by defining networks of endothelialized microchannels within matrices of type I collagen, a microfluidic vascular network (μVN). With long-term (one to two weeks) cultures of these μVNs, we demonstrate the emergence of appropriate endothelial morphology and barrier function (Fig. 1A, i). We then proceed to investigate angiogenic remodeling (Fig. 1A, ii), interactions between endothelial cells (ECs) and perivascular cells (Fig. 1A, iii), and interactions between blood components and endothelium with flow (Fig. 1A, iv). These experiments indicate recapitulation of important characteristics of microvessels observed in vivo in both healthy and pathological scenarios and suggest important biophysical mechanisms by which geometry and luminal flow define function. We discuss the potential relevance of our system for modeling tumor progression, inflammation, thrombosis, and other pathologies.

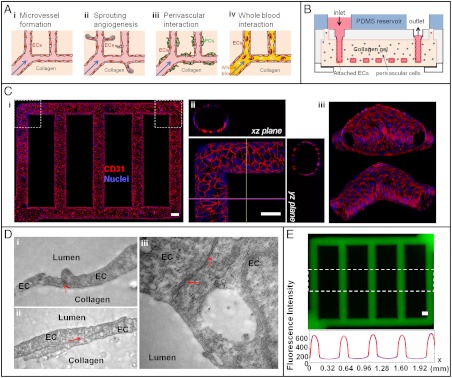

Fig. 1.

Microfluidic vessel networks (µVNs). (A) Schematic cross-sectional view of a section of µVN illustrating (i) morphology and barrier function of endothelium, (ii) endothelial sprouting, (iii) perivascular association, and (iv) blood perfusion. Arrow, Flow direction. (B) Schematic diagram of microfluidic collagen scaffolds after fabrication (detailed fabrication processes and parts in Fig. S1). (C) Z-stack projection of horizontal confocal sections of endothelialized microfluidic vessels (overall network, i) and views of corner (ii) and branching sections (iii). Red, CD31; blue, nuclei. (Scale bar: 100 μm.) (D) Transmission electron micrographs showing focal contacts (i), overlapping junctions (ii), and complex adherens junctions (iii) between endothelial cells. Magnification: 29,000×. (E) Permeability across the endothelium, perfused with 70 kDa FITC-Dextran (Upper), and corresponding fluorescence intensity (Lower) averaged over the height of the dashed box on the micrograph (analysis in SI Methods and Fig. S3 B and C). Blue and red curves correspond to the perfusion with 70 kDa Dextran at perfusion time t = 11 min and 13 min, respectively. (Scale bar: 100 μm.)

Results

Engineering μVNs in Type I Collagen.

We engineered μVNs by seeding human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) into microfluidic circuits formed via soft lithography in a type I collagen gel. Native, type I collagen at 6–10 mg/mL is of an appropriate stiffness to allow high reproducibility of vessel microstructure and also enables remodeling through degradation and deposition of extracellular matrix. The lithographic process enables the formation of endothelium along the microfluidic channels and the incorporation of living cells within the bulk collagen (Fig. 1B). The key steps in the process are definition of a microstructured silicone stamp as a master on which to mold collagen with microstructure; injection and gelation in situ of collagen with or without perivascular cells in plexiglass jigs (Fig. 1B and Fig. S1); and sealing together two collagen layers to form the enclosed fluidic structure by applying pressure within the final plexiglass device. The enclosed microstructure has an inlet and an outlet that enable the seeding of ECs and perfusion of the vessels with medium during culture (Fig. S1). ECs were cultured alone or with perivascular cells within the bulk collagen for up to two weeks with gravity-driven flow (SI Methods).

Fig. 1C presents the morphology of a μVN formed by culturing ECs alone. The vessels were fixed and stained after two weeks of culture in growth medium (SI Methods). CD31 (Fig. 1C) and VE-cadherin (Fig. S2) were both expressed in regions of EC-EC contact; this expression and localization indicates the maintenance of the endothelial phenotype and the formation of intercellular junctions between ECs (14). These proteins, which define the restrictive barrier function of the endothelium in vivo (15), were expressed throughout the whole network (Fig. 1C, i), with no detectable differences at corners (Fig. 1C, ii) or bifurcations (Fig. 1C, iii). Over the first 3 d in culture, the cross-sectional area of the microvessel expanded and changed profile from the original square cross-section defined lithographically (100 μm × 100 μm) toward an elliptical cross-section with larger dimension (150 μm × 120 μm). We observed no significant difference in the average cell size relative to that of 2D cultures (approximately 3 × 103 μm2 per cell) (16). This evolution indicates that the matrix (6–10 mg/mL collagen with modulus of 200–500 Pa) (16) possesses the appropriate stiffness and the capacity for chemical remodeling by the ECs during spreading and proliferation. The ECs in μVNs exhibit a cobble-stone pattern with no net alignment. This venule-like morphology (17) may be maintained by the low flow shear stress (18) applied (0–10 dyne cm-2 with time average of 0.1 dyne cm-2). Ultrastructural analysis of the endothelium reveals extensive intracellular junctions (Fig. 1D), including focal adherens junctions (Fig. 1D, i), overlapping junctions (Fig. 1D, ii), and complex junctions (Fig. 1D, iii). The appearance of these intercellular junctions and of pinocytotic vesicles (Fig. S2) indicates that the major systems for transport of molecules across the endothelium were intact, as expected in arterioles and capillaries (19). The absence of intraluminal projections and the normal architecture of organelles indicate that the endohelium was quiescent, as one would expect in the absence of inflammation (20).

The endothelium throughout the μVNs presented a barrier to the transfer of solutes from the lumen into the matrix. As seen qualitatively in Fig. 1E, little permeation of a macromolecule (70 kDa FITC-Dextran) occurred over intervals of a few minutes; this behavior strongly contrasts that seen in the absence of endothelium (Fig. S3). We used the distributions of fluorescence intensity during this transient to estimate the permeability coefficient of the endothelium, K [cm s-1] (SI Methods). On day 14, we obtained K values of (4.1 ± 0.5) × 10-6 cm s-1 for 70 kDa FITC-Dextran, and (7.0 ± 1.5) × 10-6 cm s-1 for 332 Da fluorescein. These permeability coefficients were approximately five times higher than reported for mammalian venules in vivo [(0.15 ± 0.05) × 10-6 cm s-1 for 70 kDa FITC-Dextran] (21), but close to those for isolated mammalian venules (approximately 2 × 10-6 cm s-1 for FITC-albumin) (22) and of endothelial monolayers formed in vitro [O(10-6) - O(10-5) cm s-1 for FITC-albumin] (7, 23). Price et al. (13) studied vessel stability as a function of pressure and shear stress and showed that low flow produced short-lived (fewer than 5 d for 80% of vessels) leaky vessels. Our vessels cultured under low flow, however, remained stable with venule and capillary-like morphology and permeability. This distinction may arise from different cell types [HUVECs here vs. human dermal microvascular endothelial cells (13)], extracellular matrices [10 mg/mL type I collagen extracted in this study (16) vs. 7 mg/mL type I collagen from BD Bioscience (13)], growth medium, fabrication [injection molding (9) vs. metal tube demolding (7)], and geometry [interconnected network vs. single tube (7, 13)].

Angiogenesis and Endothelial Cell-Perivascular Cell Interactions.

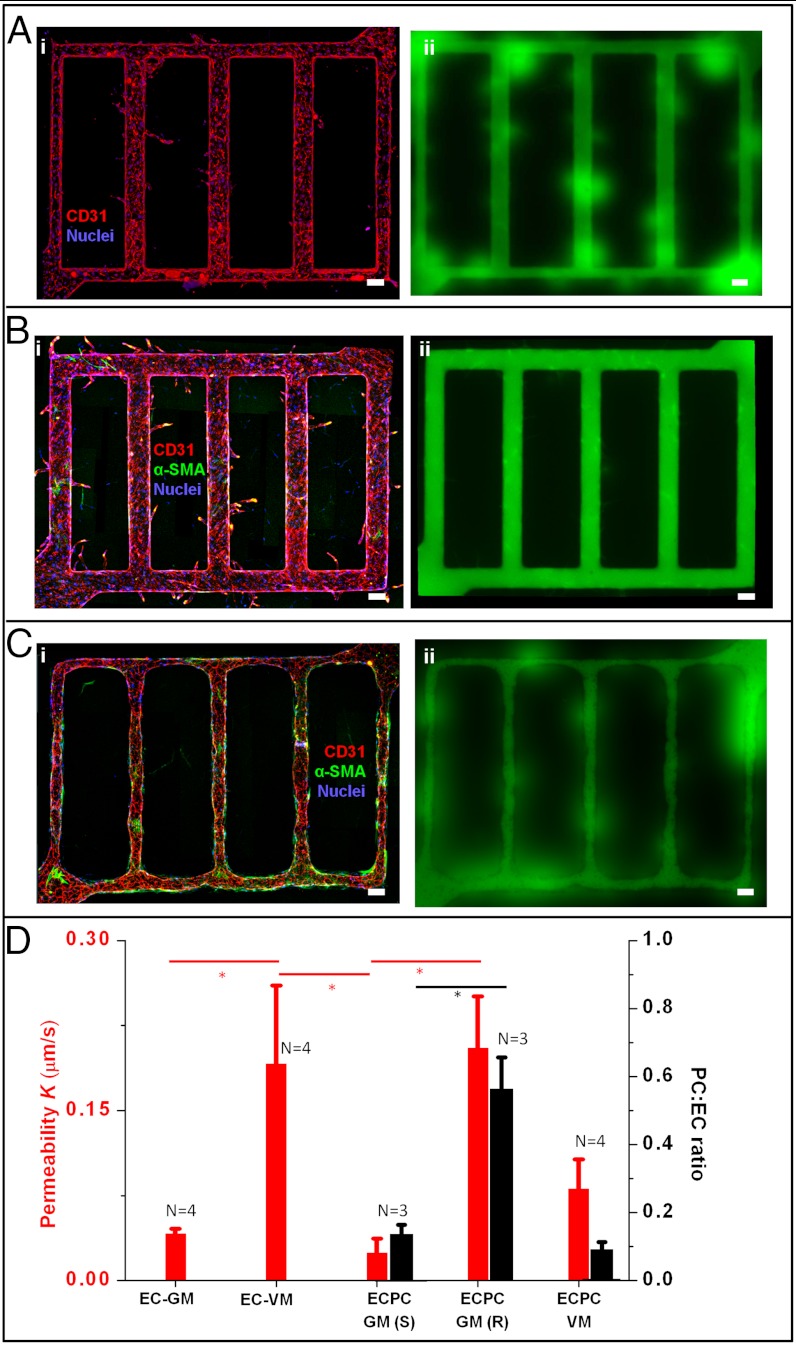

Three-dimensional system have been developed to study sprouting angiogenesis in vitro, for example, endothelial sprouting from a planar endothelium into bulk collagen gel (24), lateral endothelial sprouting into a collagen gel isolated between two microfluidic channels formed in PDMS silicone (25), and 3D endothelial sprouting from microbead supports in a bulk gel (26). None of these systems allows for the initiation of angiogenesis from native-like vessels with luminal flow and simultaneous control of the chemical and cellular microenvironment of the endothelium. We have exploited the versatility of μVNs to investigate the angiogenic response of an endothelium with and without local interactions with perivascular cells. To begin, we applied vasculogenic medium exogenously through μVNs with perfusion to mimic the proangiogenic environment found in the vicinity of ischemic tissue or solid tumors (24, 27). After a week of exposure, μVNs presented the following properties (Fig. 2A): CD31 staining at regions of cell-cell contact was less organized (Fig. 2A, i); endothelial cells sprouted into the collagen matrix with lumens (Fig. S4A); and solute dyes leaked from the vicinity of the sprouts (Fig. 2A, ii). The average length of endothelial sprouts was 75.4 ± 22.4 μm with an areal density of 41.8 ± 3.1 mm-2 (n = 4). This length was greater than that observed in a 2D sprouting assay with HUVECs in a monolayer on 10 mg/mL collagen gels at day 14, but the invasion density was similar (invasion depth = 38.0 ± 9.9 μm and invasion density = 38.8 ± 14.9 mm-2) (16). Due to the increased permeability at the projections, the spatially averaged permeability was nearly one order of magnitude greater than that of μVNs cultured in regular growth medium (Fig. 2D). Solute extravasations in regions of endothelial sprouting have been observed in vivo in the presence of strong proangiogenic signals, such as in tumor neovasculature (28).

Fig. 2.

Sprouting angiogenesis and endothelial-pericyte interactions. (A) Sprouting into bulk collagen with proangiogenic stimuli. The microvessel network was cultured for 7 d with growth medium, followed by 7 d with vasculogenic medium. (i) The z-projection of confocal images of the overall network; and (ii): permeability measurement -70 kDa FITC-Dextran leaked from microvessels, especially at regions of new sprouts. Red, CD31; blue, nuclei. (B and C) Perivascular recruitment from the collagen bulk toward endothelium, with endothelial sprouting (B) or endothelial retraction (C): (i) z-projected confocal image, and (ii) permeability measurement with perfusion of 70 kDa FITC-Dextran. Red, CD31; green, α-SMA; and blue, nuclei. (D) Permeability and ratio of associated perivascular cell to endothelial cells (PC:EC) for five conditions in µVNs. EC-GM: monoculture of ECs with growth medium; EC-VM: monoculture of ECs with vasculogenic medium; ECPC-GM(S): co-culture of ECs and pericytes with growth medium—sprouting cases; ECPC-GM(R): co-culture of ECs and pericytes with growth medium—retracted cases; ECPC-VM: ECs and pericytes co-cultured with vasculogenic medium. Red, permeability; black, PC:EC ratio. Error bar: standard error. *p < 0.05, N, number of replicates.

Interactions between ECs and perivascular cells define the structural and functional properties of microvessels (29). When we seeded human brain vascular pericytes (HBVPCs), expressing both desmin and α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) in the bulk of the collagen gels, we observed two distinct behaviors. In half of the cases (Fig. 2B, n = 3), we observed endothelial sprouting into the collagen matrix. Long sprouts, with lumens, grew into the collagen by day 14 (Fig. 2B, i. Average sprouting length of 174.3 ± 6.6 μm and density of 15.8 ± 1.2 mm-2). Brain pericytes are known to secrete both VEGF and FGF, which may have driven this sprouting, even in the absence of exogenous GFs (30). Interestingly, these sprouts displayed good barrier properties (Fig. 2B, ii): The permeability of the vessels (Fig. 2D) was similar to that of the EC-only case with growth medium and significantly lower than that obtained with exogenous growth factors. Pericytes associated sparsely with the endothelium (Figs. 2 B and S4B) and expressed both α-SMA (Fig. S4B) and desmin (Fig. S4 D and E). In the other half of the experiments (Fig. 2C, n = 3), we observed retraction of the endothelium from the walls of the microchannels (although the lumens remained open) and a complete absence of sprouts to day 14 (Fig. 2C, i). These retracted vessels were leakier (Fig. 2C, ii), with permeabilities similar to that of the EC-only vessels treated with exogenous GFs (Fig. 2D). These vessels showed significantly higher coverage by pericytes than those observed in the other half of the experiments (Fig. 2D), with the associating pericytes strongly expressing α-SMA (Fig. S4C) (and weakly expressing desmin) (Fig. S4 F and G).

The potential origins of the two distinct outcomes (sprouting and retracted) include variations in the percentage of the initial population of pericytes of a certain character (the seeding population is mixed, and one type of pericytes may express more contractile proteins in the retracted cases, for example), difference in the initial density of ECs (200 ± 100 cells/mm2), or in the structure of the collagen in which the channels were formed (e.g., variation of fiber architectures with mechanical forces, temperature and pH during gelation) (31). In support of the first possibility, we note that experiments with purified populations of smooth muscle cells (human umbilical arterial smooth muscle cells) consistently (n = 6) showed local retraction of the endothelium, luminal constriction, and the absence of sprouting (Fig. S5).

For both outcomes, ultrastructural analysis (Fig. S4 H and I) showed that the PCs were located between the collagen matrix and the ECs. In regions of close apposition of the two cell types, the ECs were polarized, with their focal adhesions anchored toward the perivascular cells. A basal lamina formed between the two cell types; this basal lamina was not detected around the vessels in areas devoid of adjacent pericytes.

When μVNs produced by coculture of ECs and HBVPCs (n = 4) were perfused with vasculogenic media, we observed sprouting with no retraction (Fig. S4 J–L). The sprouts were significantly longer and less frequent than for either the EC-only case with exogenous GFs or the EC-pericytes case without GFs (average length of 228.5 ± 35.9 μm and density of 7.2 ± 1.1 mm-2); the vessel permeability was intermediate between these two other cases (Fig. 2D). These observations suggest that pericytes modulate the response of the μVNs to proangiogenic signals. The consistently low coverage of the vessels by pericytes and the lack of a retracted state suggest that the presence of proangiogenic factors suppressed recruitment of pericytes toward the microvessels; this behavior is consistent with the observation in vivo that VEGF is a negative regulator for perivascular recruitment (32).

Blood–Endothelium Interactions.

In healthy scenarios, the endothelium provides a nonadhesive and antithrombotic interface for the transport of blood through the vessel whereas during inflammation, the endothelium promotes the formation of the thrombi via local expression and secretion of adhesive proteins (33). The interaction of blood with endothelium has been studied extensively in vitro in planar formats that lack appropriate vessel geometries or a 3D matrix (34, 35). We examined the interaction of whole blood and the endothelium in μVNs in a quiescent state (after 7 to 14 d in our standard microfluidic culture; see Methods and SI Methods) and a stimulated state induced by brief exposure to phorbol-12-myristate-13-acetate (PMA). Upon perfusion of the μVNs with whole human blood (citrate-stabilized with labeled platelets), we observed dramatically different behaviors in the two situations (Fig. 3 A–C). In untreated μVNs, the vast majority of platelets flowed past the endothelial surface without adhering (Fig. 3A, i, and Movie S1). A small portion of platelets adhered reversibly and rolled along the endothelial surfaces. Localized, firm adhesion of platelets occurred only at some EC-EC junctions and at sites of defect in the endothelium (Fig. S6 A and B), as has been reported in vivo at sites of endothelial injury (36) and on exposed subendothelial matrix (37). Neither the transient nor firm binding led to formation of aggregates larger than 10 μm (Fig. S6 A and B). In a collagen network with no endothelium, platelets immediately adhered and aggregated on the exposed collagen (Movie S2).

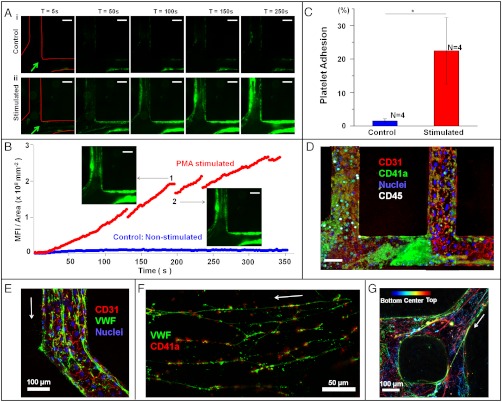

Fig. 3.

Blood-endothelial interaction. (A) Time sequences of whole blood perfusion through a μVN, either quiescent (control vessels, i) and stimulated (ii), at a flow rate of 10 μL min-1 at time points of 5 s, 50 s, 100 s, 150 s, and 250 s after initiation of perfusion. The platelets are in green, labeled with CD41a to platelet-specific glycoprotein IIb (integrin αIIb); flow direction is indicated with arrow. (Scale bar: 100 µm.) (B) Quantification of adhered platelets on the vessel wall through time in A. Blue, control vessels; red, PMA-stimulated vessels. The size and number of thrombus are proportional to the mean fluorescence intensity of labeled platelets. The fluctuation of fluorescent intensity in the PMA-stimulated vessel was caused by the embolization of platelet thrombi during blood perfusion, as indicated in the insets 1 and 2. Uniform scaling of intensity range was applied to all the images (16 bit) such that the upper and lower thresholds of the displayed intensities were 350 and 2,200, respectively. (C) Surface-covered area of adherent platelets on the vessel walls of control and stimulated vessels after 15 min of blood perfusion. Error bar: standard error. *p < 0.05, N, number of replicates. (D) Platelets and leucocytes adherent in the stimulated vessels after 1 h of blood perfusion. Leukocytes are labeled white with CD45, a leukocyte-specific member of the protein tyrosine phosphatase family. Red, CD31; green, CD41a; white, CD45; and blue, nuclei. (Scale bar: 50 μm.) (E) von Willebrand factor (VWF) was secreted from endothelial cells and assembled into fibers after activated by PMA, and the VWF fibers were aligned to the flow direction. Arrow, Flow direction. Red, CD31; green, VWF; blue, nuclei. (F) Platelet adhesion on VWF fibers. Arrow, Flow direction. Green, VWF; red, CD41a. (G) VWF fibers were either coated on the walls of the activated vessel or traveled through the lumens. The locations of VWF fibers in the vessel are color coded: Bottom in blue, center in light green, and top in red. Arrow, Flow direction.

In stimulated vessels, large aggregates of platelets formed immediately on the endothelial surface (Fig. 3A, ii, and Movie S3). In the first minutes of perfusion, these aggregates proceeded to grow to fill a substantial fraction of the lumen and then were shed into the flowing blood (Fig. 3B), possibly as a result of the rise in shear stress associated with the local decrease of lumen diameter during the formation of the thrombus (38). Platelets continued to accumulate over time on the vessel wall (Fig. 3 B and C). After 1 h of perfusion with blood, leukocytes were observed to attach on the luminal side of vessel walls and to begin migrating through the endothelium into the collagen matrix; some of the thrombi became stable (Fig. 3D and Fig. S6 C and D).

To elucidate the mechanism of thrombosis in the stimulated vessels, we perfused μVNs with FITC-conjugated antibodies against von Willebrand factor (VWF). VWF is a protein that can be released from endothelial Weibel–Palade bodies (WPBs) and assemble into fibers on the endothelial surface upon endothelial activation (34) under flow. These fibers bind platelets; leukocytes and red blood cells also accumulate at these sites, possibly by binding the adherent platelets (Fig. S6G) (39). PMA is a known secretagogue for VWF, working by activating protein kinase C. In unstimulated μVNs, we observed VWF in WPBs in the endothelial cytoplasm, but not on the endothelial surfaces (Fig. S7 A and B). In contrast, in the stimulated vessels, fibers of VWF with lengths up to 2 mm covered the surface of the vessels (Fig. 3E and Fig. S7C). These fibers bound to platelets, almost all irreversibly (Fig. 3F), as shown previously on cultured endothelial cells (34) and in mice (40). Electron micrographs illustrate the binding of platelets to the activated endothelium, with the density of bound platelets being the highest near bifurcations and vessel junctions (Figs. S6 E and F, and S7).

The importance of the 3D architecture of the μVNs manifests itself in the flow-driven pattern of VWF fibers and VWF-platelet strands observed around junctions and bifurcations in the network of vessels. Fibers that were anchored to the endothelium upstream of a bifurcation were convected off of the wall as the flow entered the junction, leading to the formation of 3D webs of fibers that traverse the lumen (Fig. 3G and Movie S3). This 3D network of VWF fibers increases the contact between the binding surfaces of the fibers and the components of the blood such that platelets are captured more efficiently and the flow is further perturbed (Fig. S7 D and E). Such structures have not been reported in planar cultures in which the flow is uniaxial and parallel to the endothelium (35), or in mouse models, where details of the progression of thrombosis have been difficult to resolve (40).

Discussion

Our lithographic approach (Fig. 1B and Fig. S1) allows for the definition of endothelialized vessels with physiologically relevant geometries such as bifurcations and junctions within a matrix that is permissive of remodeling and 3D cell culture. Our functional studies indicate the usefulness of μVNs for the study of angiogenesis (Fig. 2) in healthy (Fig. 2B) and pathological (Fig. 2A) scenarios, and thrombosis (Fig. 3) under quiescent and inflammatory conditions. Future work with μVNs could benefit from the use of alternative microfabrication techniques such as 3D printing (41) to extend the geometrical complexity of the networks.

The versatility of the μVN platform, with respect to its structure, cellular composition, and in situ control of the endothelial microenvironment, opens opportunities to address biophysical and biological questions that are difficult to access either in vivo or in conventional, planar cultures in vitro. These include the effects of geometry (42), hydrodynamic stresses, and transport processes (13, 43) on the stability of vessels, the progression of angiogenesis, and the interactions of the vessel with blood cells; and the roles of vascular cells from different organs in defining physiological and pathological states specific to those organs (for example, properties of the blood-brain barrier) (44); and the abnormal angiogenic and inflammatory profiles of solid tumors (45) and diabetic tissues (46).

As our platform matures, we anticipate that μVNs can be used to test drugs and drug-delivery strategies that target microvascular function (for example, angiogenesis (47) and hypertension) (48) or blood-endothelium interactions (for example, sickle cell disease (49) and thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura) (50). Scaffolds with μVNs could also provide a starting point for the growth of vascularized tissues in vitro for applications in regenerative medicine (51).

Methods

The microvessel networks were fabricated within native, type I collagen by molding microstructures in collagen gels with injection molding techniques (9). Human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were seeded and cultured on the walls of the microchannels created in the collagen to form an endothelialized lumen. Human brain vascular pericytes (HBVPCs) or human umbilical arterial smooth muscle cells (HUASMCs) were embedded in collagen bulk for the study of interactions between endothelium and perivascular cells. The microvessel networks were cultured with gravity-driven flow of endothelial growth media for 7 to 14 d. The angiogenesis experiments were conducted with proangiogenic media containing exogenous vascular endothelial cell growth factor (VEGF), basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), and phorbol ester (PMA). The experiments of blood-endothelium interactions were performed with reconstituted whole blood that was stabilized with 3.8% sodium citrate containing labeled platelets and leukocytes. Live imaging was performed for the permeability measurement with the perfusion of fluorescent dyes or the whole blood interactions with the microvessels. At the designated time points, the microvessel network was fixed and stained in situ with perfusion of fixatives and antibodies through the lumens, followed by the fluorescence confocal microscopy, scanning electron microscopy or transmission electron microscopy. Detailed methods are available in SI Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We acknowledge the technical assistance of G. Swan. We thank Dr. Scott Verbridge, Dr. Charles Murry, and Dr. Stephen Schwartz for helpful discussions. We acknowledge the Life Sciences Core Laboratories Center at Cornell University, and the Lynn and Mike Garvey Imaging Laboratory in the Institute of Stem Cell and Regenerative Medicine at University of Washington. We acknowledge the financial support of an American Heart Association Scientist Development Grant (Y.Z.); National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant R01HL091153 (to J.A.L.); NIH Grant RC1 CA146065; the Cornell Center on the Microenvironment and Metastasis (NCI-U54 CA143876); the Human Frontiers in Science Program; the Cornell Nanobiotechnology Center (NSF-STC; ECS-9876771); the Cornell Center for Nanoscale Science and Technology (NSF-NNIN ECS 03-35765); a New York State J.D. Watson Award (A.D.S.); and an Arnold and Mabel Beckman Foundation Young Investigator Award (A.D.S.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1201240109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100:57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Battegay EJ. Angiogenesis: Mechanistic insights, neovascular diseases, and therapeutic prospects. J Mol Med. 1995;73:333–346. doi: 10.1007/BF00192885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moake JL, et al. Unusually large plasma factor VIII: von Willebrand factor multimers in chronic relapsing thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. N Engl J Med. 1982;307:1432–1435. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198212023072306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Griffith LG, Swartz MA. Capturing complex 3D tissue physiology in vitro. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:211–224. doi: 10.1038/nrm1858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Staton CA, et al. Current methods for assaying angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Int J Exp Pathol. 2004;85:233–248. doi: 10.1111/j.0959-9673.2004.00396.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Naito Y, et al. Vascular tissue engineering: Toward the next generation vascular grafts. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2011;63:312–323. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chrobak KM, Potter DR, Tien J. Formation of perfused, functional microvascular tubes in vitro. Microvasc Res. 2006;71:185–196. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koike N, et al. Creation of long-lasting blood vessels. Nature. 2004;428:138–139. doi: 10.1038/428138a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choi NW, et al. Microfluidic scaffolds for tissue engineering. Nat Mater. 2007;6:908–915. doi: 10.1038/nmat2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harley BAC, et al. Microarchitecture of 3D scaffolds influences cell migration behavior via junction interactions. Biophys J. 2008;95:4013–4024. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.122598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Golden AP, Tien J. Fabrication of microfluidic hydrogels using molded gelatin as a sacrificial element. Lab Chip. 2007;7:720–725. doi: 10.1039/b618409j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wong KHK, Truslow JG, Tien J. The role of cyclic AMP in normalizing the function of engineered human blood microvessels in microfluidic collagen gels. Biomaterials. 2010;31:4706–4714. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.02.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Price GM, et al. Effect of mechanical factors on the function of engineered human blood microvessels in microfluidic collagen gels. Biomaterials. 2010;31:6182–6189. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.04.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ayalon O, Sabanai H, Lampugnani MG, Dejana E, Geiger B. Spatial and temporal relationships between cadherins and PECAM-1 in cell-cell junctions of human endothelial cells. J Cell Biol. 1994;126:247–258. doi: 10.1083/jcb.126.1.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dejana E. Endothelial adherens junctions: Implications in the control of vascular permeability and angiogenesis. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:1949–1953. doi: 10.1172/JCI118997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cross VL, et al. Dense collagen matrices with microstructure and cellular remodeling for three-dimensional cell culture. Biomaterials. 2010;31:8596–8607. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.07.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Caplan BA, Gerrity RG, Schwartz CJ. Endothelial cell morphology in focal areas of in vivo Evans blue uptake in young pig aorta. 1. Quantitative light microscopic findings. Exp Mol Pathol. 1974;21:102–117. doi: 10.1016/0014-4800(74)90082-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chiu JJ, Wang DL, Chien S, Skalak R, Usami S. Effects of disturbed flow on endothelial cells. J Biomech Eng. 1998;120:2–8. doi: 10.1115/1.2834303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ogawa K, Imai M, Ogawa T, Tsukamoto Y, Sasaki F. Caveolar and intercellular channels provide major transport pathways of macromolecules across vascular endothelial cells. Anat Rec. 2001;264:32–42. doi: 10.1002/ar.1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gerrity RG, Richardson M, Somer JB, Bell FP, Schwartz CJ. Endothelial cell morphology in areas of in vivo Evans blue uptake in aorta of young pigs. 2. Ultrastructure of intima in areas of differing permeability of proteins. Am J Pathol. 1977;89:313–335. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yuan W, Lv Y, Zeng M, Fu BM. Non-invasive measurement of solute permeability in cerebral microvessels of the rat. Microvasc Res. 2009;77:166–173. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2008.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu MH, Ustinova E, Granger HJ. Integrin binding to fibronectin and vitronectin maintains the barrier function of isolated porcine coronary venules. J Physiol. 2001;532:785–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0785e.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mehta D, Malik AB. Signaling mechanisms regulating endothelial permeability. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:279–367. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00012.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bayless KJ, Davis GE. Sphingosine-1-phosphate markedly induces matrix metalloproteinase and integrin-dependent human endothelial cell invasion and lumen formation in 3D collagen and fibrin matrices. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;312:903–913. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Song JW, Munn LL. Fluid forces control endothelial sprouting. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:15342–15347. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1105316108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roukens MG, et al. Control of endothelial sprouting by a Tel-CtBP complex. Nat Cell Biol. 2010;12:933–942. doi: 10.1038/ncb2096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vailhe B, Vittet D, Feige JJ. In vitro models of vasculogenesis and angiogenesis. Lab Invest. 2001;81:439–452. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3780252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McDonald DM, Baluk P. Significance of blood vessel leakiness in cancer. Cancer Res. 2002;62:5381–5385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stratman AN, Malotte KM, Mahan RD, Davis MJ, Davis GE. Pericyte recruitment during vasculogenic tube assembly stimulates endothelial basement membrane matrix formation. Blood. 2009;114:5091–5101. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-222364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dore-Duffy P, Katychev A, Wang XQ, Van Buren E. CNS microvascular pericytes exhibit multipotential stem cell activity. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26:613–624. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williams BR, Gelman RA, Poppke DC, Piez KA. Collagen fibril formation—optimal in vitro conditions and preliminary kinetic results. J Biol Chem. 1978;253:6578–6585. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Greenberg JI, et al. A role for VEGF as a negative regulator of pericyte function and vessel maturation. Nature. 2008;456:809–U101. doi: 10.1038/nature07424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wagner DD, Frenette PS. The vessel wall and its interactions. Blood. 2008;111:5271–5281. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-078204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dong JF, et al. ADAMTS-13 rapidly cleaves newly secreted ultralarge von Willebrand factor multimers on the endothelial surface under flowing conditions. Blood. 2002;100:4033–4039. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang J, Roth R, Heuser JE, Sadler JE. Integrin alpha(v)beta(3) on human endothelial cells binds von Willebrand factor strings under fluid shear stress. Blood. 2009;113:1589–1597. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-05-158584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosenblum WI, et al. Role of platelet-endothelial cell adhesion molecule (PECAM) in platelet adhesion aggregation over injured but not denuded endothelium in vivo and ex vivo. Stroke. 1996;27:709–711. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.4.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ruggeri ZM, Mendolicchio GL. Adhesion mechanisms in platelet function. Circ Res. 2007;100:1673–1685. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000267878.97021.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ruggeri ZM, Orje JN, Habermann R, Federici AB, Reininger AJ. Activation-independent platelet adhesion and aggregation under elevated shear stress. Blood. 2006;108:1903–1910. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-011551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lopez JA, Chen JM. Pathophysiology of venous thrombosis. Thromb Res. 2009;123:S30–S34. doi: 10.1016/S0049-3848(09)70140-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Motto DG, et al. Shigatoxin triggers thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura in genetically susceptible ADAMTS13-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2752–2761. doi: 10.1172/JCI26007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu W, DeConinck A, Lewis JA. Omnidirectional printing of 3D microvascular networks. Adv Mater. 2011;23:H178–H183. doi: 10.1002/adma.201004625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nelson CM, Bissell MJ. Of extracellular matrix, scaffolds, and signaling: Tissue architecture regulates development, homeostasis, and cancer. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2006;22:287–309. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.22.010305.104315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Culver JC, Dickinson ME. The effects of hemodynamic force on embryonic development. Microcirculation. 2010;17:164–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1549-8719.2010.00025.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Persidsky Y, Ramirez SH, Haorah J, Kanmogne GD. Blood-brain barrier: Structural components and function under physiologic and pathologic conditions. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2006;1:223–236. doi: 10.1007/s11481-006-9025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stroock AD, Fischbach C. Microfluidic culture models of tumor angiogenesis. Tissue Eng Part A. 2010;16:2143–2146. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2009.0689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yamagishi S, Imaizumi T. Diabetic vascular complications: Pathophysiology, biochemical basis and potential therapeutic strategy. Curr Pharm Des. 2005;11:2279–2299. doi: 10.2174/1381612054367300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ferrara N, Hillan KJ, Novotny W. Bevacizumab (Avastin), a humanized anti-VEGF monoclonal antibody for cancer therapy. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;333:328–335. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.05.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.McLaughlin VV, et al. Efficacy and safety of treprostinil: An epoprostenol analog for primary pulmonary hypertension. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2003;41:293–299. doi: 10.1097/00005344-200302000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bunn HF. Mechanisms of disease—pathogenesis and treatment of sickle cell disease. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:762–769. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709113371107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen J, et al. N-acetylcysteine reduces the size and activity of von Willebrand factor in human plasma and mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:593–603. doi: 10.1172/JCI41062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Levenberg S, et al. Engineering vascularized skeletal muscle tissue. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:879–884. doi: 10.1038/nbt1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.